Scholars of American politics have long debated the nature and extent of party polarization in the American electorate, but the majority tend to agree that the mass public has become more divided along partisan and ideological lines.Footnote 1 In addition to this partisan-ideological polarization, Democrats and Republicans have come to increasingly dislike and even abhor each other, a distinct trend labeled affective polarization.Footnote 2 Recent work shows that bias, aversion and hostility toward partisan opponents have escalated substantially among average citizens, leading to more anger, negative stereotyping, political activism, out-party discrimination and in-party favoritism.Footnote 3

Affective polarization is clearly on the rise, and studies show that strong or sorted partisans are more likely to drive this trend.Footnote 4 Even after modeling these predictors, however, substantial variance remains in the level of partisan bias and hostility citizens display. This raises the specific question of why some Americans are more divided than others, despite expressing the same strength of partisanship and ideology. It also highlights the broader question of what drives affective polarization.

While previous work has focused on the divisive influence of partisan strength, partisan-ideological sorting, negative political campaigns, partisan media, or personality dispositions,Footnote 5 we theorize in this article that the moralization of politics further heightens affective polarization. Recent work in moral psychology indicates that moral conviction is a distinctive dimension of attitude strength, which might recruit the type of psychological processes that would induce polarizing judgements.Footnote 6 Building on this research, we theorize that opinions based on partisan moral convictions – perceptions that the parties and their affiliates are moral concerns – are more likely to engender polarized views than opinions based on personal preferences or group norms. As a result, individuals across the range of partisan strength are more likely to show antipathy toward the out-party and favoritism toward the in-party if they base their partisan evaluations on their deeply held beliefs about right and wrong.

Based on this theory, we hypothesize that citizens who tend to moralize politics will express more biased evaluations of the two parties and their leaders than citizens who rarely moralize politics. They will also display more social distance from and hostility toward opposing partisans in everyday life. Using data from national samples drawn in 2012 and 2016, including novel measures of affective polarization among the American public, we find support for these expectations. Individuals who express a higher propensity to moralize politics display a wider gap in partisan affect, greater divide in presidential approval, and more relationship distance, social media distance, anger, incivility and antagonism toward partisan opponents.

The results of this study suggest that citizens are now divided along moral as well as partisan lines. Even after controlling for strength of partisanship and ideology, people who frequently moralize politics display considerably higher levels of affective polarization than people who rarely moralize politics. While moral divisions in American politics typically refer to competing values or worldviews,Footnote 7 this study indicates a different divide based on the extent to which citizens’ political attitudes stem from their beliefs about right and wrong. This finding is important because it helps us understand how moral conviction contributes to the divisive political climate we see today. At a time when political candidates are strategically framing everything from income inequality to immigration as moral concerns, the results also raise key normative questions about attempts to moralize politics for electoral gain.

AFFECTIVE POLARIZATION

Traditionally, party polarization has been defined as partisan-ideological or policy-based divisions between the Democratic and Republican parties. Scholars have assessed polarization in the mass public based on the extent to which voters have sorted into the correct party and ideology, or by how much consistency they show in aligning their issue positions and their party identification across a range of issues.Footnote 8 These partisan-ideological and policy-based definitions of polarization have prompted much of the debate over the existence and extent of polarization in the American electorate.

More recently, however, some political scientists have specified affective polarization as a separate dimension of partisan division in the mass public. Alternatively labeled behavioral polarization,Footnote 9 social polarizationFootnote 10 and partisan prejudice,Footnote 11 affective polarization refers to increasing levels of antipathy toward opposing partisans and favoritism toward copartisans.Footnote 12 Whereas polarization typically implies distance on an ideological or policy-preference scale, affective polarization points to the growing social distance between the parties.

While scholars might debate the extent of partisan-ideological and policy-based polarization in the American electorate, studies show that partisan bias and animosity have increased substantially over the last four decades among average citizens.Footnote 13 This affective polarization predicts more hostile rhetoric, greater political activism, avoidance of partisan opponents and preferential treatment of copartisans.Footnote 14 Perhaps most concerning, affective polarization now permeates relationship dynamics and everyday situations. Partisans are increasingly uncomfortable with their children marrying members of the opposite party, they attribute negative stereotypes to out-party supporters and they are willing to discriminate against opposing partisans in nonpolitical scenarios.Footnote 15 Iyengar and Westwood even present evidence that partisan hostility among average citizens now matches or exceeds racial animus.Footnote 16

Despite the clear rise in affective polarization, not all Americans display such partisan animosity. For example, weak partisans who are ideologically inconsistent and politically unengaged are less likely to display out-party antipathy than strong partisans who are ideologically consistent and politically engaged.Footnote 17 In order to explain the rise as well as the variance in partisan hostility, some studies suggest that partisan sorting or ideological division drives affective polarization, encouraging stronger political identities and more one-sided evaluations.Footnote 18 Others indicate that the act of identifying with a political party triggers negative evaluations of the out-party, which are then reinforced by exposure to negative political campaigns, partisan media coverage and closely contested elections.Footnote 19 These theories generally ascribe the roots of affective polarization to increasing partisan or ideological alignment and strength. Even when partisanship and ideology are modeled, however, substantial variance remains to be explained in the level of partisan bias and hostility citizens display.

To complement these theories, we posit that another factor besides partisan or ideological strength influences affective polarization: the moralization of politics. Some citizens develop moral convictions along party lines, meaning they come to view their party and its affiliates as morally good and the rival party and its affiliates as morally bad. Individuals who base their opinions about the political parties, party leaders and party members on their fundamental beliefs about right and wrong are more likely to show antipathy toward opposing partisans and favoritism toward copartisans than individuals who base their opinions on nonmoral concerns. While stronger partisans might hold more polarized attitudes than weaker partisans, we expect citizens to display more affective polarization, irrespective of partisan strength, if their partisan evaluations stem from moral convictions rather than personal preferences or normative conventions.

THE MORALIZATION OF POLITICS

In recent years, studies have shown that people develop political opinions based on moral convictions, not just personal preferences, group norms, religious beliefs or individual values.Footnote 20 Moral conviction is defined as a person’s perception that an attitude is grounded in his or her core beliefs about right and wrong, and substantial evidence suggests it is a unique construct.Footnote 21 Moral conviction does not reduce to religious commitment, religious beliefs, personality traits, partisan strength or other dimensions of attitude strength like extremity, importance, certainty or centrality.Footnote 22 Morally convicted attitudes, or attitudes held with strong moral conviction, are unique from other attitudes in that people experience them as objectively true, universally applicable, inherently motivating, strongly tied to emotions and uniquely independent of external influences.Footnote 23 Also, moral conviction scores distinctively correlate with the type of physiological arousal we would expect from a moral way of thinking, which suggests that moral convictions are tied to moral processing in a way that other important and extreme attitudes are not.Footnote 24

When it comes to partisan evaluations, some people base their opinions of the political parties and their members on personal preferences or normative conventions, while others base their opinions on core moral beliefs. These latter individuals develop what we define as partisan moral convictions, or the perceptions that their attitudes about the political parties, party leaders and party members are connected to their fundamental sense of right and wrong. They come to view their party and its supporters as fundamentally good and the other party and its adherents as fundamentally bad. Because moralized attitudes trigger punitive and unyielding responses, people who base their political opinions on partisan moral convictions are more likely to display affectively polarized evaluations. We expound upon this point further below.

In order for people to develop partisan moral convictions, the political parties and their affiliates have to get linked to people’s underlying mental systems for processing morality.Footnote 25 This means that partisan objects have to be presented in such a way that they trigger emotions and evaluations that signal they should be considered objects of moral concern. There are multiple mechanisms by which this process of moralization might occur in the American political system. First, people often hear partisan objects being described by family, friends and the media in moral terms like right and wrong or good and evil. Over time, these conversations might build up a mental connection between an attitude object like a party or candidate and a sense that the object is moral or immoral. Second, political parties and leaders provide cues about their moral stances through the positions they take on various issues, which individuals may or may not perceive as moral concerns.Footnote 26 If a candidate adopts strong and visible positions on issues that people view as matters of right and wrong, then he or she might get linked by association to morality in people’s minds. Third, party labels send signals about politicians’ character traits.Footnote 27 These cues about whether a politician is honest or dishonest, fair or discriminatory, might influence people to develop the perception that the politician is moral or immoral. Fourth, principles from social identity theory suggest that mere identification with a party might motivate partisans to evaluate in-party members as moral and out-party members as immoral.Footnote 28 In this case, party labels themselves would provide sufficient cause for citizens to classify partisans as objects of moral concern.Footnote 29

While the current political environment is ripe for individuals to develop partisan moral convictions, some people are more likely to base their partisan opinions on their sense of right and wrong than others. Studies show substantial variance in people’s propensity to moralize different political issues, causes and candidates.Footnote 30 Individuals who express a greater tendency to moralize politics, or to habitually think about politics in terms of right and wrong, should more readily associate partisan objects like party leaders and members with their core moral beliefs and convictions. Consequently, they should be more likely to develop partisan moral convictions, which in turn influence them to evaluate copartisans more positively and opposing partisans more negatively.

PARTISAN MORAL CONVICTIONS AND AFFECTIVE POLARIZATION

People who develop morally convicted attitudes about the political parties and their affiliates are more likely to display the bias, aversion and animosity that characterize affective polarization. Moralized attitudes trigger more hostile opinions, negative emotions, and punitive actions than attitudes based on preferences or conventions alone.Footnote 31 People who hold strong moral convictions want greater social and physical distance from, they show greater intolerance towards and they display greater willingness to discriminate against those who have conflicting views.Footnote 32 Also, they are less likely to cooperate or compromise with opposing sides.Footnote 33 In addition, moral conviction motivates acceptance of punitive responses like retribution, vigilantism and violence.Footnote 34 Finally, moralized attitudes evoke particularly strong negative emotions and judgements like anger, disgust and blame.Footnote 35

At the same time, however, moralized attitudes can also have a positive effect on social interactions. While people tend to dislike and distance themselves from individuals who hold a different moral perspective, they seem to like and be drawn toward individuals who hold similar moral beliefs.Footnote 36 As a result, moral conviction causes people to adopt more hostile positions toward those they perceive to be on the wrong side, but it also encourages them to adopt more favorable stances toward those they perceive to be on the right team.

Because morally convicted attitudes lead individuals to respond in more polarized ways than otherwise strong but nonmoral attitudes, people who base their partisan evaluations on their beliefs about right and wrong should be more likely to display positive feelings toward copartisans and negative feelings toward opposing partisans than people who base their partisan evaluations on nonmoral values. Much more is at stake when you think one party is good and the other is evil than when you think one party is preferable to the other. More hostility is provoked when a party leader violates what you hold to be sacred than when a party leader violates what you consider to be important. For this reason, we expect that partisan moral convictions heighten affective polarization over and above the effects of partisan and ideological strength.

If this theory is accurate, it should help explain current signs of affective polarization. First, citizens are increasingly divided in their partisan evaluations, expressing more positive affect toward their own party and more negative affect toward the opposing party.Footnote 37 Second, Democrats and Republicans are more deeply divided over presidential job performance, expressing more approval for in-party presidents and less approval for out-party presidents.Footnote 38 Third, partisans display more social distance from each other, expressing reluctance for their children to marry into the out-party.Footnote 39 Fourth, citizens exhibit more hostile emotions and behaviors toward opposing partisans, directing anger at the out-party and discriminating against opposing partisans in nonpolitical scenarios.Footnote 40

We expect that partisan moral convictions help drive these indices of affective polarization, and two points from our theory suggest how. First, individuals who routinely moralize politics should be more likely to hold morally convicted attitudes about different partisan objects, including the candidates and officials associated with a party. Second, based on what we know about the divisive attributes of moralized attitudes, these partisan moral convictions should engender more polarized evaluations. This means that partisan moralizers should express more negative affect toward the out-party and its affiliates, whom they perceive to be morally wrong, while they should express more positive affect toward the in-party and its affiliates, whom they perceive to be morally right. They should also report lower approval ratings of out-party leaders and higher approval ratings of in-party leaders for the same reason. As a result, people who frequently moralize politics should be more biased in their partisan evaluations than people who rarely moralize politics, leading us to predict:

HYPOTHESIS 1: Propensity to moralize politics will increase the gap in partisan affect.

HYPOTHESIS 2: Propensity to moralize politics will increase the partisan divide in presidential approval.

Partisan moral convictions should also engender more negative responses toward average citizens who side with the opposing party. Citizens who frequently moralize politics are more likely to view out-party members as immoral rivals who support what is wrong and oppose what is right. Since moralized attitudes uniquely facilitate social distance from and hostility toward those who are deemed morally wrong,Footnote 41 the moralization of politics should heighten these indices of affective polarization in everyday life. Therefore, we posit:

HYPOTHESIS 3: Propensity to moralize politics will increase social distance from opposing partisans.

HYPOTHESIS 4: Propensity to moralize politics will increase hostility toward opposing partisans.

These expectations should hold for partisans on both sides. Despite findings that liberals and conservatives display different cognitive styles,Footnote 42 these distinctions do not translate to differences in partisans’ tendency to base their attitudes on moral concerns.Footnote 43 In fact, Skitka and colleagues report that liberals and conservatives display the same propensity to moralize politics, and moralized attitudes trigger the same political effects on both the left and the right.Footnote 44 Consequently, partisan moral convictions should heighten affective polarization among Democrats and Republicans.

DATA AND MEASURES

We utilize data from two samples to test these expectations: the 2012 American National Election Studies (ANES) Evaluations of Government and Society Study (EGSS) and a national sample of 1,011 respondents collected by Survey Sampling International (SSI) in November 2016.Footnote 45 The 2012 EGSS is one of the only national studies to include survey items that assess respondents’ tendency to both moralize politics and display partisan bias, and the 2016 SSI instrument also includes items to assess both constructs. Together, the two samples allow us to test whether the same pattern of results holds at different time periods and in relatively different political contexts.

To operationalize the key explanatory variable propensity to moralize, we use the EGSS’s Moralization of Politics (MOP) scale, which is a battery of questions that evaluate respondents’ level of moral conviction on different political issues.Footnote 46 One of the challenges of measuring moral conviction in political contexts is that a person might moralize one political issue, such as a union worker moralizing collective bargaining rights, but not politics in general. The MOP scale is designed to navigate this obstacle by tapping into respondents’ general tendency to think about different political objects in moral terms.

To start off, respondents are shown a list of ten issues: the budget deficit, the war in Afghanistan, education, health care, illegal immigration, the economic recession, abortion, same-sex marriage, the environment and unemployment. Then, they are asked to report which issue they think is the most important one facing the country and which issue they think is the least important. Next, they are asked to answer how much their opinion on an issue is based on their ‘moral values’ in reference to three issues from the original list of ten: the issue they identified as most important, the issue they identified as least important and one other randomly selected issue. For each of these issues, respondents answer on a five-point scale ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘a great deal’. We take the average of these answers to get an overall propensity to moralize score for each respondent, which is coded to range from 0 to 1, or the lowest to highest propensity to moralize politics.

To operationalize propensity to moralize in the SSI sample, respondents are asked about their moral conviction on eleven political issues: same-sex marriage, abortion, the environment, the minimum wage, immigration, gun control, health care, physician-assisted suicide, equal pay for women, free trade agreements and the budget deficit. They report how much their opinion on each issue reflects their ‘core moral beliefs and convictions’ and connects to their ‘fundamental beliefs about right and wrong’, answering both items on the same five-point scale as in the EGSS. Following standard practice, responses to both items are averaged to form a moral conviction score for each issue.Footnote 47 These eleven scores are then averaged to form one propensity to moralize score for each respondent, which is coded to range from 0 to 1, or the lowest to highest propensity to moralize.Footnote 48

In both the EGSS and SSI samples, the MOP scale provides a basic measure of respondents’ average tendency to link their political opinions to their core moral beliefs and convictions, which gives a rough indication of their proclivity to think about politics in moral terms. For this reason, we expect that propensity to moralize captures a habitual orientation to moralize different political objects. If this is true, individuals who are high on the scale should be more likely to hold partisan moral convictions. They should also be more likely to display the signs of affective polarization that our theory predicts.

Despite previous evidence that propensity to moralize captures a unique construct,Footnote 49 questions remain whether the measure really taps into people’s underlying sense of morality, versus other dimensions of attitude strength. Recent evidence from a physiological response study indicates that moral conviction items, like those used to operationalize propensity to moralize, capture a distinctly moral attitude dimension.Footnote 50 In this study, moral conviction scores uniquely correlate with the type of physiological arousal we would expect from a deontological way of thinking, which is focused on rules of right and wrong that are impervious to consequences. This finding suggests that morally convicted attitudes are tied to moral processing in a way that other important and extreme attitudes are not, and it indicates that we can use survey items like the MOP battery to evaluate moral conviction.

We assess the gap in partisan affect using a common measure of affective polarization: the difference in respondents’ ratings of Democrats and Republicans on a feeling thermometer scale ranging from 0 to 100, or very unfavorable to very favorable feelings.Footnote 51 The EGSS sample lacks feeling thermometers for the political parties, but it does include feeling thermometers for the leading candidates in the 2012 Democratic and Republican presidential primaries, Barack Obama, Mitt Romney and Newt Gingrich. The SSI sample includes feeling thermometers for the 2016 Democratic and Republican presidential candidates, Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump, as well as for the Democratic and Republican parties. For each set of thermometers, we calculate the difference between respondents’ ratings of the respective Democratic and Republican candidates or the Democratic and Republican parties.Footnote 52 Net thermometer scores are coded to range from 0 to 1, where 0 reflects no difference in partisan affect, and 1 reflects the widest gap in partisan affect.

To evaluate the partisan divide in presidential approval, we use an EGSS question asking respondents to what extent they ‘approve, disapprove, or neither approve nor disapprove of the way Barack Obama is handling his job as president’. Scores range from ‘disapprove extremely strongly’ to ‘approve extremely strongly’ on a seven-point scale, which is recoded on a 0 to 1 scale. We assess the partisan gap in presidential approval by comparing President Obama’s approval rating among Democrats and Republicans.

We operationalize social distance from and hostility toward opposing partisans using novel items on the SSI instrument, which allow us to assess how much partisan distance, negative emotion, uncivil speech and antagonistic behavior characterize relationships among the American public.Footnote 53 Compared to feeling thermometers and approval ratings, these measures provide a more direct appraisal of affective polarization in people’s everyday lives.

First, we assess social distance in face-to-face and online interactions. Relationship distance is operationalized by asking respondents how ‘hesitant’ they are to date an opposing partisan. Social media distance is evaluated by asking respondents how frequently they ‘block friends on Facebook and Twitter if they talk positively about [the out-party]’.

Second, we evaluate hostility in emotions, speech and behavior. Anger is operationalized by asking respondents how frequently they get angry ‘just thinking about’ members of the out-party. Incivility is measured by asking respondents how often they have ‘made fun of [Democrats/Republicans]’ over the course of the election. Antagonism is evaluated by asking respondents how often they have worn apparel ‘hoping it would upset’ opposing partisans.

Responses to each of the social distance and hostility items range from ‘never’ to ‘always’ on a five-point scale. They are recoded on a 0 to 1 scale, where 0 represents the least polarized, and 1 represents the most polarized response for a given indicator. Democrats, Republicans and party leaners are assigned the appropriate out-party for these questions based on their self-reported party identification, and Independents are assigned opposing partisans based on their answer to a question asking which party they would ‘absolutely not vote for’.Footnote 54

The social distance and hostility items can be used to form one measure of affective polarization in everyday life (Cronbach’s α=0.87), but we treat them as individual measures to parse out the effects of moralizing politics on different aspects of partisan division.Footnote 55 On average, respondents are more likely to report private forms of affective polarization in everyday life, like feeling angry toward opposing partisans, and less likely to report public forms of affective polarization in everyday life, like wearing apparel to antagonize opposing partisans. Independent samples t-tests reveal that, on average, Democrats report significantly higher levels of relationship distance, social media distance, incivility and antagonism than Republicans.Footnote 56 There is no significant difference, however, in the average anger expressed by partisans on either side.Footnote 57

In order to verify that moral conviction heightens affective polarization over and above partisanship and ideology, we control for partisan strength and ideological strength, which we form by folding standard seven-point party identification and ideology items at their midpoint.Footnote 58 These four-point measures are coded to range from 0 to 1, where 0 represents independent partisanship or moderate ideology, and 1 represents strong partisanship or extreme ideology. The results of this analysis would likely be strengthened by the inclusion of social identity-based measures of partisanship and ideology, which have been shown to better predict affective polarization than traditional measures of partisan and ideological strength.Footnote 59 Despite this limitation, there is reason to expect that moral conviction distinctly heightens affective polarization.Footnote 60

In addition to partisan and ideological strength, we control for several other factors that might influence the electorate’s in-party and out-party evaluations. Demographic controls include race (white), gender (female), age and education. To account for respondents’ familiarity with politics, we control for political knowledge, measured by summing correct answers to four standard knowledge items. To ensure that religious commitment and conservatism are not driving results, we control for church attendance and religious affiliation (evangelical).Footnote 61 The results would likely be strengthened by a control for authoritarianism, which is another potential predictor of affective polarization,Footnote 62 but the EGSS and SSI samples lack this measure. Still, evidence indicates that propensity to moralize is a distinct construct from personality traits like authoritarianism and should thus have a unique effect in heightening partisan division.Footnote 63 All controls are coded on a 0 to 1 scale for ease of comparison, and missing data are imputed using the Amelia II software package, creating twenty-five datasets.Footnote 64

ANALYSES AND RESULTS

We utilize linear regression to test the marginal effect of propensity to moralize on the gap in partisan affect, partisan divide in presidential approval, social distance from opposing partisans and hostility toward opposing partisans. Each of the outcome variables are regressed on propensity to moralize, partisan strength, ideological strength and the other control variables. We use weighted OLS for the 2012 EGSS data.Footnote 65 Filling in either the gap in partisan affect, social distance or hostility as the dependent variable, we model:

$$\eqalignno{ DV_{i} \,{\equals}\, & \beta 0\:\,{\plus}\,\:\beta 1\,Propensity\,to\,Moralize_{i} \,{\plus}\,\beta 2\;Partisan\,Strength_{i} \cr &{\plus}\, \beta 3\;Ideological\,Strength_{i} \,{\plus}\,\beta 4\;Controls_{i} \:\,{\plus}\,e_{i} $$

$$\eqalignno{ DV_{i} \,{\equals}\, & \beta 0\:\,{\plus}\,\:\beta 1\,Propensity\,to\,Moralize_{i} \,{\plus}\,\beta 2\;Partisan\,Strength_{i} \cr &{\plus}\, \beta 3\;Ideological\,Strength_{i} \,{\plus}\,\beta 4\;Controls_{i} \:\,{\plus}\,e_{i} $$

Since we only have job approval ratings for President Obama in 2012, we run a slightly different model to assess the effect of moralizing politics on the partisan divide in presidential approval. To evaluate the gap between in-party and out-party ratings, we include a dichotomous variable for party identification, which we interact with the propensity to moralize score. Republicans and Republican leaners are coded 1, and Democrats and Democratic leaners are coded 0. Independents and ‘other’ party identifiers are excluded from this analysis.Footnote 66 Setting presidential approval as the dependent variable, we model:

$$\eqalignno{ DV_{i} \,{\equals} \,& \beta 0\,{\plus}\,\beta 1\;Republican_{i} \,{\plus}\,\beta 2\;Propensity\,to\,Moralize_{i} & \cr &{\plus}\, \beta 3\;Partisan\,Strength_{i} \,{\plus}\,\beta 4\;Ideological\,Strength_{i} \cr &{\plus}\beta 5\;\left( {Republican_{i} } \right.{\asterisk} \left. { & Propensity\,to\,Moralize_{i} } \right),{\plus}\:\beta 6\;Controls_{i} \,{\plus}\;e_{i} $$

$$\eqalignno{ DV_{i} \,{\equals} \,& \beta 0\,{\plus}\,\beta 1\;Republican_{i} \,{\plus}\,\beta 2\;Propensity\,to\,Moralize_{i} & \cr &{\plus}\, \beta 3\;Partisan\,Strength_{i} \,{\plus}\,\beta 4\;Ideological\,Strength_{i} \cr &{\plus}\beta 5\;\left( {Republican_{i} } \right.{\asterisk} \left. { & Propensity\,to\,Moralize_{i} } \right),{\plus}\:\beta 6\;Controls_{i} \,{\plus}\;e_{i} $$

The results presented in Figure 1 support our first hypothesis that the propensity to moralize politics increases the gap in partisan affect.Footnote 67 Each point in a coefficient plot in Figures 1, 3 and 4 shows the estimated effect of a predictor on the respective outcome variable, and each line indicates the 95 per cent confidence interval for an estimate. The left-hand plot in Figure 1 indicates that propensity to moralize significantly heightens polarized feelings toward the Democratic and Republican presidential primary candidates, Obama and Romney/Gingrich, in 2012. The center and right-hand plots demonstrate that this pattern of biased evaluations continues in 2016. Propensity to moralize significantly widens the gap in affect toward the Democratic and Republican presidential candidates, Clinton and Trump, as well as the gap in ratings of the parties themselves. Moving from the lowest propensity to moralize score to the highest increases the gap in partisan affect, on average, 0.11, 0.17 and 0.13 points on a one-point scale in each respective model.

Fig. 1. Propensity to moralize politics increases the gap in partisan affect Note: All variables coded 0 to 1. Models are OLS (weighted OLS for 2012 Candidate Gap). 95 per cent confidence intervals constructed based on Rubin’s (Reference Rubin1987) combination rules to account for imputation uncertainty. R2=0.19, N=1,253 for 2012 Candidate Gap. R2=0.20, N=1,011 for 2016 Candidate Gap. R2=0.32, N=1,011 for 2016 Party Gap.

These findings hold even after controlling for the strength of partisanship and ideology, as well as religious commitment and conservatism. In both the 2012 and 2016 candidate models, the impact of propensity to moralize on polarized evaluations is half as strong as the impact of traditionally dominant partisan strength, and it is a third as strong in the 2016 party model. In both the 2016 candidate and party models, the impact of propensity to moralize on partisan bias is greater than that of ideological strength, and it is only slightly less in the 2012 candidate model. In all three models, the effect of moralizing politics on the gap in partisan affect surpasses the effect of church attendance and evangelical affiliation. These findings of more divided feelings along moral lines in both 2012 and 2016, despite the controls, lend evidence to our theory that partisan moral convictions heighten affective polarization over and above factors like partisanship and ideology.Footnote 68

The results illustrated in Figure 2 support our second expectation that moralizing politics increases the partisan divide in presidential approval. The figure shows the estimated marginal effect of propensity to moralize on President Obama’s 2012 job approval rating among Democrats and Republicans, holding control variables constant at their means. In this plot, the x-axis illustrates the observed range of propensity to moralize, and the y-axis shows the observed range of Obama’s approval rating. The thick dashed line represents the marginal effect of propensity to moralize on presidential approval for Democrats, and the thick solid line represents this effect for Republicans. The thin dashed and solid lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals, and the slightly jittered rug plot on the x-axis reflects the distribution of propensity to moralize scores.

Fig. 2. Propensity to moralize politics increases the partisan divide in presidential approval Note: Variables coded 0 to 1. Model is weighted OLS. Thin dashed and solid lines represent 95 per cent confidence intervals constructed using Rubin’s (Reference Rubin1987) combination rules. Partisan differences in the effect of moralizing are significant (p<0.01). R2=0.45. N=1,233.

As Figure 2 shows, the gap between how Democrats and Republicans rate President Obama’s job performance grows wider as you move from left to right across the propensity to moralize scale. The solid line shows that moving from the lowest to highest propensity to moralize score leads, on average, to a −0.10 point decrease in Obama’s approval rating among Republicans, while the dashed line illustrates that this same move leads, on average, to a 0.12 point increase in Obama’s approval rating among Democrats. This finding illustrates that partisans who habitually think about politics in terms of right and wrong are more divided over presidential job performance, even after we control for partisan strength, ideological strength and religiosity.

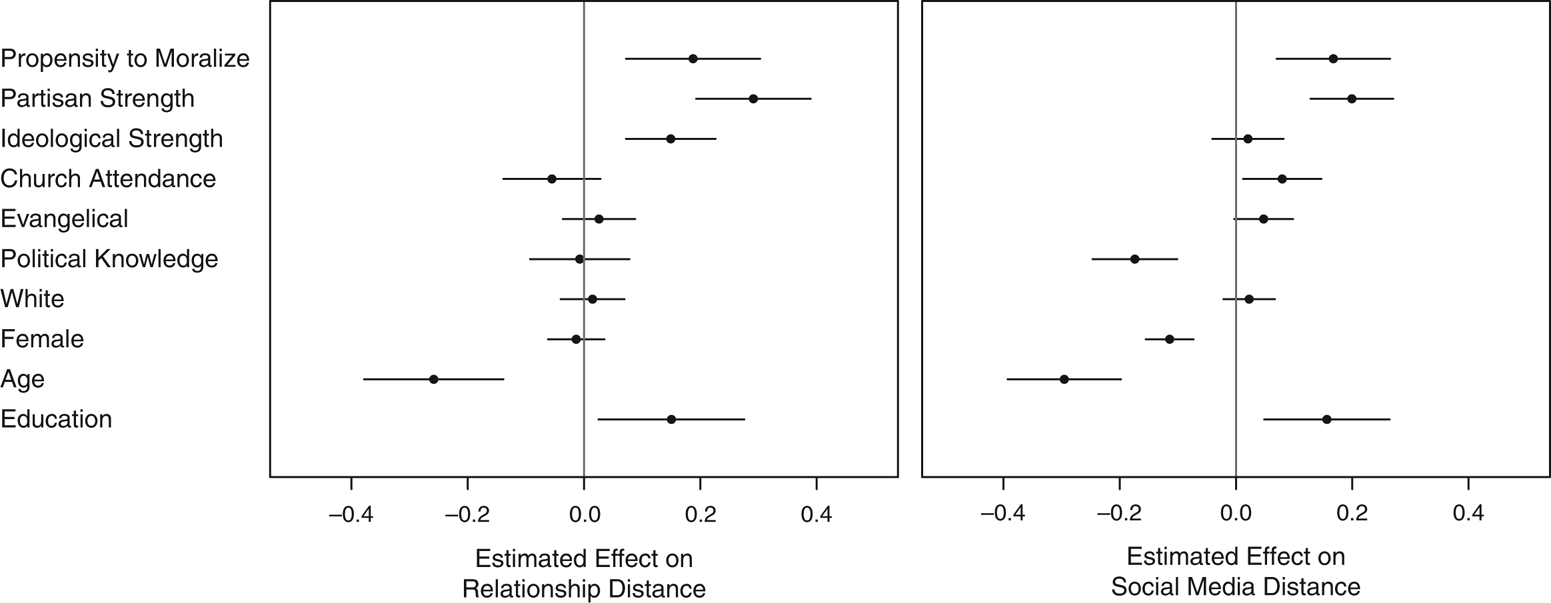

The results presented in Figure 3 support our third hypothesis that propensity to moralize politics increases social distance from opposing partisans. This finding holds whether social distance is measured based on dating relationships or social media interactions. The left-hand plot shows that propensity to moralize significantly heightens hesitancy to date opposing partisans by 0.19 points, on average, across the one-point scale of relationship distance. The right-hand plot shows that propensity to moralize significantly increases willingness to block friends who support the out-party on social media by 0.17 points, on average, across the one-point scale of social media distance.

Fig. 3. Propensity to moralize politics increases social distance from opposing partisans Note: All variables coded 0 to 1. Models are OLS. 95 per cent confidence intervals constructed based on Rubin’s (Reference Rubin1987) combination rules to account for imputation uncertainty. R2=0.19, N=1,011 for Relationship Distance. R2=0.21, N=1,011 for Social Media Distance.

Comparing the influence of propensity to moralize to that of partisan strength, ideological strength and religiosity shows that only partisan strength has a larger impact on social distance in either model. Even then, the effect of propensity to moralize is nearly two-thirds that of partisan strength in the relationship model, and it is only slightly less than that of partisan strength in the social media model. In both models, the impact of moralizing politics on social distance is larger than that of ideological strength, church attendance and evangelical affiliation. These results indicate that habitually thinking about politics in moral terms increases social distance from partisan opponents, even after controlling for strength of partisanship and ideology and religious commitment and conservatism. Again, moralized attitudes heighten a key indicator of affective polarization – this one directed at average citizens who side with the opposing party.

The results depicted in Figure 4 support our final expectation that propensity to moralize politics increases hostility toward opposing partisans, encouraging more inimical emotions, speech and behavior. The left-hand, central and right-hand plots in the figure show that propensity to moralize significantly heightens out-party anger, incivility and antagonism by an average of 0.20, 0.29 and 0.19 points, respectively, across the one-point scales of anger, incivility and antagonism.

Fig. 4. Propensity to moralize politics increases hostility toward opposing partisans Note: All variables coded 0 to 1. Models are OLS. 95 per cent confidence intervals constructed based on Rubin’s (Reference Rubin1987) combination rules to account for imputation uncertainty. R2=0.17, N=1,011 for Anger. R2=0.14, N=1,011 for Incivility. R2=0.30, N=1,011 for Antagonism.

The impact of propensity to moralize on hostility toward opposing partisans once again rivals the impact of other political and religious predictors. Moralizing politics leads to more anger, incivility and antagonism across party lines than ideological strength, religious attendance and evangelicalism. While tendency to moralize has a slightly weaker effect on anger than partisan strength, it actually has the same or greater effect in motivating antagonistic behavior and uncivil speech. These results provide further evidence that moral conviction increases affective polarization in everyday life, driving more hostile responses toward members of the opposing party.

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Together, the results of this study provide evidence to support our theory. People who tend to perceive political issues as matters of right and wrong are more likely to display partisan bias and animosity than people who rarely moralize politics. This pattern applies to evaluations of the political parties and their candidates and, more troublingly, to interactions with opposing partisans in everyday life. Across measures of partisan affect, presidential approval, social distance and hostility, morally convicted individuals are more polarized than their nonmorally convicted counterparts. This suggests that citizens who base their political opinions on partisan moral convictions are more likely to exhibit affective polarization than citizens who base their opinions on personal preferences or normative conventions. These findings pose important implications and raise further questions for how we think about political polarization, moral conviction and electoral politics.

First, this study suggests another factor besides famously dominant partisan strength that drives affective polarization. While strength of partisanship significantly influences partisan bias, distance and hostility, propensity to moralize also significantly affects these outcomes. In the cases of social media distance, anger, incivility and antagonism, the effect of moralizing politics rivals that of partisan strength. After controlling for strength of partisanship and ideology, we still find that the more people moralize politics, the more partisan bias, division and animosity they display. These results implicate moral conviction as a key factor that heightens affective polarization above and beyond what strong partisanship and ideology do alone.

Insights from this study about the divisive impact of moral conviction help clarify the debate over the extent of mass polarization in the United States. While political scientists have argued back and forth for years, it appears by now that much of the dispute over the existence of electoral polarization ultimately stems from disagreements about terms. Levels of partisan prejudice and antipathy, which characterize affective polarization, have clearly increased in the American electorate, while citizens’ issue positions, which define policy-based polarization, remain relatively moderate.Footnote 69

Results from this study suggest we should not be surprised by this pattern of polarization. Citizens can agree on a majority of political issues, yet still be bitterly divided because they disagree about the parties, leaders and policies they consider to be matters of right and wrong. Also, partisans can perceive that one side is moral, and thus admirable, and the other side is immoral, and thus loathsome, without holding highly constrained, ideologically extreme issue attitudes. In this way, the polarizing effect of partisan moral convictions helps shape the political landscape we see today – a nation that agrees on many things but is still deeply divided.

Second, findings from this study suggest that citizens are split along moral as well as partisan lines. A substantial gap exists between how moralizers and nonmoralizers view opposing partisans, which is a different moral divide than the culture war cleavages that typify discussions of morality and politics. When we control for partisan and ideological strength, people who hold few moral convictions are less biased in their evaluations of the parties and their leaders. They also display less social distance from and hostility toward opposing partisans. In contrast, people who habitually moralize politics are more one-sided in their partisan evaluations, and they display more distance from and hostility toward out-party members. Previous work shows that different values or worldviews divide the American public.Footnote 70 This study suggests that a separate moral gap, one between citizens who moralize and do not moralize politics, qualifies the intensity of partisan division.

This gap raises normative questions about effective political representation. While many citizens are turned off by partisan division and desire greater co-operation across party lines, citizens who moralize politics are more likely to oppose compromise at all costs.Footnote 71 When deciding whose views to represent, politicians have an electoral incentive to avoid alienating morally convicted individuals, who are more likely to participate in political campaigns and turn out to vote.Footnote 72 Consequently, political leaders might eschew bipartisan activities in government for what they view as an electoral advantage. In this scenario, the interests of nonmoralizers are left poorly represented in government because citizens who tend to moralize politics are more electorally valuable.

The results of this study also point to several questions that are ripe for further investigation. First, questions remain about the polarizing effect of moralized attitudes in models that include multi-item scales of partisan identity, which are better predictors of partisan rivalry, anger and activism than traditional measures of partisan strength.Footnote 73 Findings from this study indicate that moral conviction is a distinct construct that heightens affective polarization. Even if the polarizing effect of moral conviction is dampened in models that include social identity-based measures of partisanship, however, there is still reason to expect that moralized attitudes help drive partisan division. Studies show that moral perceptions powerfully influence social identities,Footnote 74 so partisan moral convictions should strengthen partisan identities, which also heighten partisan hostility. Future work should investigate the link between moralized attitudes, partisanship and affective polarization.

Second, this study raises questions about how partisan moral convictions develop. Principles from social identity theory suggest that the moralization and resulting one-sided view of partisan objects could occur because people who tend to moralize politics are more likely to maximize perceived in-group similarities and out-group differences on the attribute of morality, causing them to view the in-party as fundamentally moral and the out-party as fundamentally immoral.Footnote 75 If this is the case, party labels should be sufficient to help link partisans and politicians to people’s sense of right and wrong, and moralizers should display the same biased assessments of all party affiliates.Footnote 76

This theory might explain how generic Democrats and Republicans, known by little more than their party ties, become moralized, but the results of this study suggest a different model by which specific party leaders become moralized. Propensity to moralize predicts more divided evaluations of Trump and Clinton in 2016 than Obama, Romney and Gingrich in 2012. Whether this finding reflects a short-term increase due to the vitriolic nature of the 2016 election, a long-term trend in growing levels of partisan bias or differences in the EGSS and SSI samples, it very tentatively suggests that people held stronger moral convictions about the candidates in 2016 than in 2012. This result points to a model where people must build up a mental association between party leaders and a sense that the leaders are morally right or wrong. As a result, factors like national prominence, the tone of media coverage, moralized campaign rhetoric and tighter associations with a party should help facilitate the connection between certain party leaders and citizens’ moral intuitions. Future work should investigate this expectation in order to better understand how the moralization of politics occurs, which in turn heightens affective polarization.

In conclusion, findings from this study raise two important normative questions about the nature of moral conviction and electoral politics. First, how can we moderate the affective polarization triggered by partisan moral convictions while also respecting individuals’ core moral beliefs about the political parties and their affiliates? Over the last few decades, the American electorate has grown increasingly divided along partisan lines, showing greater hostility toward partisan foes and greater favoritism toward partisan allies.Footnote 77 Perhaps most troubling, this trend now includes aversion to average citizens, not just political leaders and groups, who are perceived to side with the wrong political party.Footnote 78 This study suggests that people’s deeply held beliefs about right and wrong facilitate heightened levels of affective polarization toward both party leaders and members, adding to the long list of moral conviction’s negative consequences.Footnote 79

Before we jump to encourage individuals to moderate their moral beliefs, however, we have to remember that moral convictions have positive implications as well. They encourage political participation,Footnote 80 motivate collective action to challenge disadvantageFootnote 81 and serve as an information shortcut that facilitates coherent political opinions.Footnote 82 Also, some of the most important advances in our country’s history, such as the Civil Rights Movement, have occurred because people were willing to stand up for their fundamental beliefs about right and wrong.Footnote 83

Second, how can politicians leverage the increased political participation and activism engendered by moral conviction without contributing to affective polarization? This question is particularly important at a time when politicians are framing everything from fracking to free trade agreements and college costs to gun control as moral concerns. It might be electorally advantageous for political elites to moralize party platforms, issues and campaigns. At the same time, however, we have to ask whether this strategy is normatively beneficial for the country as a whole. As this study shows, a moralized political climate makes it easier for citizens to firmly support their political side, but it also makes it easier for them to demonize the opposition.