Mainstream Western European parties are increasingly struggling to appeal broadly and hold together their base of support (Bale and Krouwel Reference Bale and Krouwel2013; Hobolt and Tilley Reference Hobolt and Tilley2016; Pardos-Prado Reference Pardos-Prado2015; Somer-Topcu Reference Somer-Topcu2015). In the French elections of 2017, traditional mainstream parties all but collapsed. In the 2017 German elections, both the center-left and center-right achieved their worst results in decades. Similar developments have taken place across Western Europe, from Sweden in the North to Italy in the South.

Two theoretical approaches address these developments. Dealignment theory posits that voters, unburdened by stable commitments, have defected from mainstream parties and are floating freely in the electoral space (Dalton and Wattenberg Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2000). In contrast, the globalization-driven realignment argument proposes that the electorate has reorganized into two blocs: globalization losers and globalization winners (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008). Although both arguments advance our understanding of electoral politics, each has limitations. The former paints an overly disorganized image of the electorate, with no clear predictions for voting patterns. And in the face of increased electoral fragmentation, the latter proposes an overly organized image of the electorate, with voters too neatly sorted into two main blocs.

As an alternative lens for considering the remaking of West European electoral politics, I focus on cross-pressured voters: those who hold conservative and progressive attitudes on different issues. A substantive share of the electorate is cross-pressured: it is either welfare chauvinist, combining cultural conservatism with progressive economic views, or market cosmopolitan, bundling economic conservatism with progressive cultural values (Federico, Fisher and Deason Reference Federico, Fisher and Deason2017; Hillen and Steiner Reference Hillen and Steiner2019; Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2005; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2004; Kurella and Rosset Reference Kurella and Rosset2017; Malka, Lelkes and Soto Reference Malka, Lelkes and Soto2019; Surridge Reference Surridge2018; van der Brug and van Spanje Reference van der Brug and van Spanje2009). In line with dealignment theory, this focus on cross-pressures acknowledges that voters are spread across the ideological space – yet without assuming they no longer hold stable electoral preferences. And like realignment theory, it takes seriously the role of identity-related concerns – yet without assuming they divide the electorate into two blocs.

Analyzing survey data collected over 25 years, I show that West European politics is characterized by an asymmetry: while support for the left is common among voters with progressive attitudes on all issues, it is enough to be conservative on one issue to turn right. This is because cross-pressured voters tend to attribute greater importance to issues on which they hold conservative attitudes (Shayo Reference Shayo2009) and therefore turn right. There are thus many ways to be right, as the right attracts not only voters with consistent conservative attitudes but also welfare chauvinists and market cosmopolitans.

This asymmetry in public opinion, in turn, has implications for the challenges and opportunities of center-right parties. On the one hand, center-right parties are better positioned than the center-left to attract cross-pressured voters, since these voters already self-identify with the right. Yet on the other hand, center-right parties compete with other parties on the right for cross-pressured voters and may find themselves increasingly torn between welfare chauvinists and market cosmopolitans, since movement toward one group of cross-pressured voters may alienate the other.

Uncovering the asymmetric structure of mass attitudes across the left–right divide entails exploring two issues in the electoral politics literature. The first issue relates to the development of European party systems. A prominent argument posits that the right's inability to speak in a single voice has been a source of weakness (Castles Reference Castles1978). Yet in a multidimensional electoral space with many cross-pressured voters, the ability of the right to speak in multiple voices is a source of strength, which expands its base of support.

The second issue relates to the rise of the radical right. One influential account traces support for the radical right to the defection of welfare chauvinist, working-class voters from the center-left (Fraser Reference Fraser2017; Streeck Reference Streeck2017). Yet as demonstrated below, welfare chauvinists also tend to identify with the right where and when a radical right party is not available. While center-right parties traditionally absorbed the support of many welfare chauvinists (Beer Reference Beer1965; Lipset Reference Lipset1959), these voters are now increasingly represented by the radical right. Seen from this perspective, the rise of radical right parties may portend not so much a mass defection of welfare chauvinists from the center-left but rather the disintegration of the center-right (Bale Reference Bale2018; Evans and Mellon Reference Evans and Mellon2016; Gidron and Ziblatt Reference Gidron and Ziblatt2019).

Theoretical Expectations

Extant research provides conflicting predictions regarding cross-pressured voters: some expect them to prioritize economic attitudes, others hypothesize that they prioritize cultural values, and others predict they adopt a centrist position.Footnote 1 These perspectives all share the same starting point: since the left is associated with progressive positions and the right with conservative ones, cross-pressured voters have to decide which attitudes to prioritize when choosing between left and right (Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014; Thomassen Reference Thomassen2012).

Some expect voters to prioritize their economic preferences. Historically, economic issues have played a crucial role in European politics (Cusack, Iversen and Rehm Reference Cusack, Iversen and Rehm2006). Research in American politics shows that voters prioritize attitudes on economic issues even following the ‘Culture Wars’ of the 1980s, which increased the salience of cultural issues (Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder2006; Bartels Reference Bartels2006; McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal Reference McCarty, Poole and Rosenthal2006).

Others suggest that voters prioritize cultural issues, since it is harder to compromise on cultural identities than on taxes and welfare (Goren and Chapp Reference Goren and Chapp2017; Tavits Reference Tavits2007). There is evidence that poor religious voters follow their (conservative) cultural views rather than their (progressive) economic attitudes (De La, Lorena and Rodden Reference De La O and Rodden2008). Research that argued for this cultural bias mostly focused on welfare chauvinists (Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014). Yet it follows from this perspective that just as welfare chauvinists (culturally conservative) turn right, market cosmopolitans (culturally progressive) should turn left.

Alternatively, cross-pressured voters may average out their conservative and progressive attitudes and adopt a centrist position: Treier and Hillygus (Reference Treier and Sunshine Hillygus2009, 696) note that Americans ‘with divergent economic and social preferences are more likely to call themselves moderate than to use a liberal or conservative label’. From this perspective, a centrist ideological position often reflects a ‘meeting place’ for voters who are cross-pressured between conservative and progressive attitudes (Cochrance Reference Cochrance2015, 138)

An Alternative: Right-Wing Asymmetric Advantage – with a Caveat

To understand the political behavior of cross-pressured voters, the core question then is: to which dimension do these voters attach more salience when choosing which party to vote for? As Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann (Reference Lefkofridi, Wagner and Willmann2014) explain, if cross-pressured voters attach more salience to economic issues they would support the party that most closely represents their economic views, and if they attach more salience to cultural issues they will support the party that best represents their cultural values. Yet different cross-pressured voters are likely to systematically attach more salience to some issues than others, which allows us to generate predictions about the electoral behavior of cross-pressured voters.

There are theoretical reasons to expect that welfare chauvinists will attach greater salience to the cultural dimension, while market cosmopolitans will see economic issues as more salient to their vote. Especially relevant is the model developed by Shayo (Reference Shayo2009), according to which the salience voters attach to different dimensions is endogenous to their socio-demographic characteristics. Within this model, voters identify with either their economic or cultural identity; greater identification with one identity translates into lower identification with the other (Han Reference Han2016). Since being poor confers low status, less well-off voters identify with their cultural identity; and since being rich confers high status, better-off voters are likely to prioritize their economic identities.

While Shayo (Reference Shayo2009) focuses on explaining support for redistribution, his model is highly relevant for explaining electoral behavior and vote choice. In terms of their demographics, welfare chauvinists tend to be less well-off while market cosmopolitans are better off (Baldassarri and Goldberg Reference Baldassarri and Goldberg2014). Bringing these demographics together with Shayo's model, it follows that less well-off, welfare chauvinist voters are likely to attach greater salience to the cultural dimension, on which they are conservative, and turn right, while well-off market cosmopolitan voters are likely to put more weight on their economic preferences, on which they are conservative, and also turn right. Thus, while previous work expects cross-pressured voters to follow the issue most salient to them, we can expect salience to vary systematically across cross-pressured voters in a way that would nudge them to the right.

One caveat is in order: in multiparty systems, center-right parties – namely Christian Democrats and conservatives – may not be the main beneficiaries of this right-wing advantage among cross-pressured voters. Center-right parties nowadays often combine moderate conservative positions on both economic and cultural issues (Gidron and Ziblatt Reference Gidron and Ziblatt2019). As Pardos-Prado (Reference Pardos-Prado2015) demonstrated, center-right parties indeed benefit when these ideological dimensions are strongly bundled; other parties on the right reap the benefits of disalignment between dimensions of electoral competition. This reflects a broader finding in the electoral politics literature, according to which mainstream parties struggle when dimensions of electoral competition are misaligned (de Vries and Hobolt Reference de Vries and Hobolt2012).

Theoretical Expectations and their Observable Implications

The literature generates conflicting expectations: (1) some expect voters to prioritize economic preferences; (2) others predict that voters will follow their cultural preferences; (3) still others expect cross-pressured voters to be centrists. Alternatively, I hypothesize that (4a) cross-pressured voters prefer the right over the left, since both welfare chauvinists and market cosmopolitans are likely to view issues on which they are conservative as more salient to their vote choice; and (4b) compared to other right-of-center parties, center-right parties are likely to be less appealing to cross-pressured voters.

Figure 1 presents the observable implications of the theoretical arguments discussed above. The y-axis denotes the probability of identifying with the right. The x-axis ranges across the different combinations of economic and cultural attitudes: from welfare chauvinism to market cosmopolitanism, with bundled attitudes (either progressive or conservative) in the middle. Below, I construct an empirical variable that similarly ranges from welfare chauvinism to market cosmopolitanism. Note that the theoretical argument generates predictions for the two extremes of this scale (unbundled attitudes) but not to the middle of the scale (bundled attitudes).

Figure 1. Contrasting observable implications.

If cross-pressured voters follow their economic preferences, those who are economically conservative and culturally progressive will identify with the right, while those who are economically progressive and culturally conservative will identify with the left (Figure 1A). If voters follow their cultural values, those who are economically conservative and culturally progressive will identify with the left, while those who are economically progressive and culturally conservative will identify with the right (Figure 1b). If cross-pressures generate ambivalence, cross-pressured voters will adopt a centrist position (Figure 1c). Yet if cross-pressures are resolved in favor of the right, both welfare chauvinists and market cosmopolitans will turn right (Figure 1d).

Data and Measurement

In order to test these predictions regarding the political behavior of cross-pressured voters, I analyze data from the European Values Study (EVS) collected in Western Europe in 1990–1993 [1990] and 2017 (EVS 2015; EVS 2019). The following ten countries were included in both waves: Austria, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, Spain and Great Britain. The EVS is suited for this analysis since the same questions on economic and cultural issues were asked over a period of more than 25 years.

The dependent variable is a 10-point scale of left–right self-identification (below, I report the results of analyses in which the dependent variable is vote choice). The majority of the public in Western Europe can locate itself on the left–right scale (Best and McDonald Reference Best, McDonald, Dalton and Anderson2010). Notwithstanding arguments about its decline in post-industrial democracies (Hellwig Reference Hellwig2008), left–right identification remains a very strong predictor of vote choice: citizens who identify with the right (left) tend to vote for right (left) parties (Dalton Reference Dalton, Dalton and Anderson2010).

The key independent variable is a measure of cross-pressures on the economic and cultural dimensions. I construct standardized scales for attitudes on economic and cultural issues for survey respondents in both the 1990 and 2017 samples; higher values on both scales indicate more conservative attitudes. A factor analysis of ten questions reveals that attitudes in 1990 and 2017 were constructed along two dimensions: one economic, which pertains to state intervention in the economy, and one cultural, which deals with gender norms and attitudes toward foreigners (see Appendix Table 1 for the factor scores, Eigenvalues and question wording). A composite index of attitudes decreases measurement error compared to relying on single questions (Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder2008).Footnote 2

I use the factor scores to construct two measures of cross-pressures. First, I follow Hillen and Steiner (Reference Hillen and Steiner2019) and classify respondents into four quadrants based on their relative positions within their countries. Welfare chauvinists have economic views below the 40th percentile (that is, more progressive economic attitudes) and cultural views above the 60th percentile (more conservative cultural attitudes), while market cosmopolitans have economic views above the 60th percentile and cultural views below the 40th percentile. Consistent conservatives are those with economic and cultural attitudes above the 60th percentile, while consistent progressives have economic and cultural attitudes below the 40th percentile. This classification excludes respondents whose attitudes are around the median and therefore produces a conservative estimate of the share of cross-pressured voters.

Classifying respondents as welfare chauvinists or market cosmopolitans provides a useful measure of the share of cross-pressured voters. Yet it also requires setting arbitrary cut-off points for these categories.Footnote 3 In addition, this measure says little about the intensity of cross-pressures at the individual level. To address these issues, I construct a continuous measure of cross-pressures. Following Baldassarri and Goldberg (Reference Baldassarri and Goldberg2014), I take the difference between economic and cultural attitudes; I refer to this measure as ΔEC. Since the two attitudinal scales are standardized and range from progressive to conservative, values around zero on ΔEC reflect strong attitude bundling, with similar preferences (progressive or conservative) on both dimensions. Welfare chauvinists have negative values on the ΔEC scale, while market cosmopolitans have positive values. This ΔEC ranges from welfare chauvinism to market cosmopolitanism, similar to the x-axis in Figure 1.

Identifying Cross-Pressured Voters

Mass attitudes in Western Europe had unbundled between 1990 and 2017: the correlation between economic and cultural attitudes had dropped from 0.35 in 1990 to 0.12 in 2017. This finding is in line with previous work that documented decreasing correlations between economic and cultural attitudes in Europe (Bartels Reference Bartels2013; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2008).

The share of both market cosmopolitans and welfare chauvinists increased between 1990 and 2017, as shown in Table 1. The share of market cosmopolitans increased from 8 per cent to 14 per cent, while the share of welfare chauvinists increased from 9 per cent to about 15 per cent. The share of cross-pressured respondents in 2017 is very similar to the numbers reported by Hillen and Steiner (Reference Hillen and Steiner2019), which rely on different survey data.

Table 1. Share of cross-pressured voters

Cross-pressures are linked with distinct demographics: welfare chauvinists have lower education and income levels, while market cosmopolitans are characterized by higher education and income levels, as shown in Appendix Table 1. This is consistent with evidence that income and education push voters in opposite directions: higher income predicts conservative economic views, while higher education predicts progressive cultural attitudes (Häusermann and Kriesi Reference Häusermann, Kriesi, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015; Kitschelt and Rehm Reference Kitschelt and Rehm2014).

According to the theoretical expectations, cross-pressured voters should differ in the issues they care more about: welfare chauvinists were expected to attach greater importance to their cultural identity, while market cosmopolitans were expected to prioritize their economic identity. To test this prediction, I analyze a survey question from the EVS 2017 that asked respondents how important work and religion are in their lives. As shown in Appendix Table 4, market cosmopolitans perceive work as significantly more important and religion as significantly less important compared to other respondents. In contrast, welfare chauvinists indicate that religion is significantly more important compared to other respondents. This is in line with the expectation that different groups of cross-pressured voters differ in the salience they attach to economic and cultural issues.

To summarize, attitudes on economic and cultural issues are unbundling and the share of cross-pressured voters has been on the rise. Cross-pressures are linked with specific demographics and social identities: market cosmopolitans have higher income and education levels and are more attached to their economic identity, while welfare chauvinists have lower income and education levels, and attach greater importance to cultural issues. In the next section I examine the electoral implications of these differences across cross-pressured voters.

Cross-Pressures and Left–Right Orientations

To test the predictions regarding cross-pressured voters' left–right orientations, I first regress left–right self-identification on the four attitudinal categories presented above: consistent progressive (which serves as the reference category), consistent conservative, market cosmopolitans and welfare chauvinists. The results are presented in Table 2. All models include country fixed effects and survey weights. Standard errors are clustered by country. In Models 1–4, the dependent variable is a continuous measure of left–right identification. To address the concern that these models may capture movements within (rather than across) the left and right blocs, Models 5–8 use linear probability models with a binary dependent variable for identification with right, cutting the left–right self-identification scale in the middle.Footnote 4

Compared to respondents with consistent progressive attitudes, voters with consistent conservative attitudes are about 30 per cent more likely to identify with the right in both 1990 and 2017, once we account for individual-level covariates (Models 6 and 8). Market cosmopolitans are about 27 per cent more likely to identify with the right compared to consistent progressives. Welfare chauvinists were 15 per cent more likely to identify with the right compared to consistent progressives in 1990, and 19 per cent more likely to identify with the right in 2017. Notwithstanding differences between 1990 and 2017, the similarities over this time period stand out: cross-pressures on the economic and cultural dimensions tend to resolve in favor of the right.

Table 2. Cross-pressures and left-right self-identification (quadrants)

Note: regression analyses with country fixed effects and survey weights, standard errors clustered by country. Source: European Values Survey, 1990 and 2017. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

To further test the relationship between cross-pressures and left–right identification, I turn to the continuous measure of cross-pressures. As explained above, the ΔEC ranges from welfare chauvinism (negative values) to market cosmopolitanism (positive values); values around 0 represent strongly bundled attitudes. I regress left–right self-identification on ΔEC and the results are presented in Table 3. All models include country fixed effects and survey weights. Standard errors are clustered by country.

Table 3. Cross-pressures and left-right self-identification

Note: regression analyses with country fixed effects and survey weights, standard errors clustered by country. Source: European Values Survey, 1990 and 2017. *p < 0.1, ** p < 0.05, *** p < 0.01

The squared ΔEC term is positive in all models, suggesting that support for the right is higher among respondents who hold a combination of conservative and progressive attitudes on economic and cultural issues. Figure 2 presents the predicted probabilities of identifying with the right while moving along the ΔEC scale, holding other variables constant in both 1990 and 2017, based on Models 6 and 8 in Table 3, respectively.Footnote 5 The rug at the bottom of the figure presents the distribution of respondents on the ΔEC scale in 1990, and the rug at the top represents the distribution of respondents on the ΔEC scale in 2017. These results show that the right attracted cross-pressured voters in 1990 and more so in 2017, in line with the expectation that welfare chauvinists care more about cultural issues and turn right, while market cosmopolitans prioritize economic issues and also turn right.

Figure 2. Predicted probabilities of identifying with the right, 1990 and 2017.

Note: predicted values based on Models 6 (1990) and 8 (2017) in Table 3.

Cross-Pressures and Voting

The analyses reported above support the expectation that different combinations of conservative and progressive attitudes are resolved in favor of the right. But which parties benefit the most from this right-wing advantage among cross-pressured voters? Previous work suggests that mainstream parties, including center-right parties, struggle when dimensions of electoral competition are misaligned (de Vries and Hobolt Reference de Vries and Hobolt2012; Pardos-Prado Reference Pardos-Prado2015).

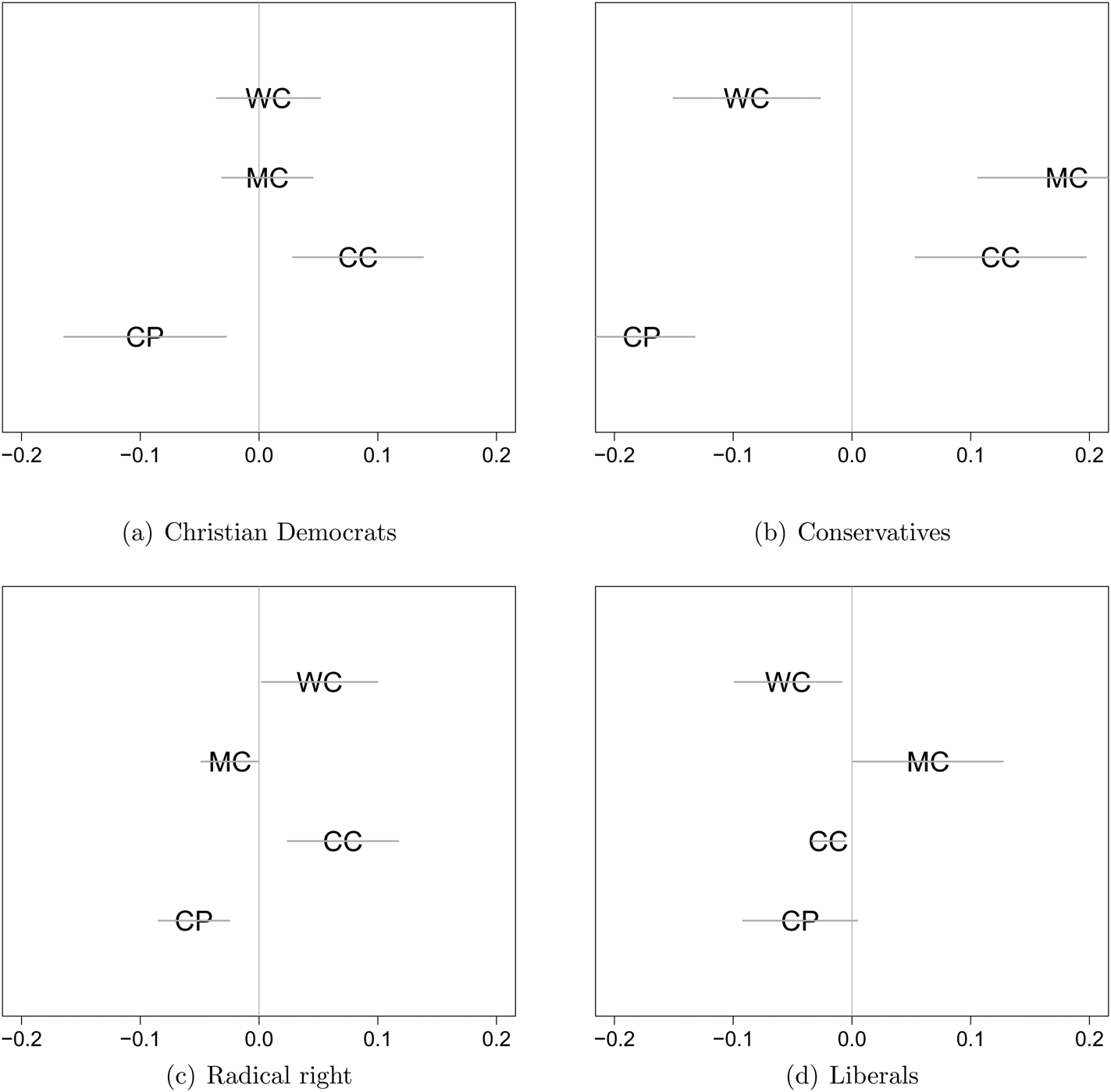

To explore this question, I analyze data from the 2017 EVS and create binary variables of voting for four major right-of-center European party families: Christian Democrats, conservatives, liberals and the radical right.Footnote 6 To examine the relationship between vote choice and cross-pressures, I use the same measures developed above to identify respondents who are welfare chauvinists and market cosmopolitans, next to those who are consistent progressives and consistent conservatives. I regress vote choice separately on each of these four attitudinal categories and include the same individual-level controls reported above in each regression model (Figure 3). The full regression models are reported in the Appendix. In each regression, I subset the data for countries in which the relevant parties are found. Standard errors are clustered by country.

Figure 3. Cross-pressures and parties on the right

Note: based on estimations in Appendix Tables 5–8. WC = welfare chauvinists; MC = market cosmopolitans; CC = consistent conservatives; CP: consistent progressives. The gray bars represent the 95 per cent confidence intervals.

A division of labor emerges on the right, as different parties appeal to voters with different combinations of attitudes. Christian Democrats (Figure 3a) enjoy an advantage among consistent conservatives. However, Christian Democrats do not strongly appeal to cross-pressured voters, in contrast to other parties on the right. Conservative parties (Figure 3b) enjoy a high level of support from both consistent conservatives and market cosmopolitans. Radical right parties (Figure 3c) attract both consistent conservatives and welfare chauvinists, in line with research on the growing support for the radical right among working-class voters (Oesch and Rennwald Reference Oesch and Rennwald2018; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2012). Market cosmopolitans support liberal parties (Figure 3d) (Giger and Nelson Reference Giger and Nelson2011).

These individual-level findings complement the country-level results in Pardos-Prado (Reference Pardos-Prado2015), who documents a positive relationship between support for the radical right and lower correlations across partisan positions on economic and cultural issues.Footnote 7 Yet these results also suggest that conservative parties may be better positioned to deal with the challenge of attitudinal cross-pressures compared to Christian Democrats, at least in terms of attracting market cosmopolitans.

No such division of labor emerges among parties left of the center: parties on the left compete for the same pool of consistently progressive voters, while those on the right divide the rest of the electorate between them, including different types of cross-pressured voters. The results for left-wing parties are presented in the Appendix. When controlling for individual-level covariates, only consistent progressive attitudes predict voting for social democratic, green and radical left parties. No left-leaning parties have an advantage among cross-pressured voters – either welfare chauvinists or market cosmopolitans.

Robustness Checks

The previous analyses showed that cross-pressures are resolved in favor of the right. It may be that cross-pressured voters, and specifically welfare chauvinists, identify with the right only because some radical right parties recently adopted more centrist and blurred positions on economic issues next to their very conservative cultural stands (Harteveld Reference Harteveld2016; Schumacher and van Kersbergen Reference Schumacher and van Kersbergen2016). In this case, welfare chauvinists would identify with the right only in party systems with radical right parties. In contrast, I expect that cross-pressures are resolved in favor of the right across different electoral contexts, including those without a radical right party. Indeed, there is evidence that cross-pressured voters turn right in the United States, with its strict two-party system (Baldassarri and Goldberg Reference Baldassarri and Goldberg2014).

To examine this point, I run similar analyses to those in Table 3 after subsetting the data to two countries with the most different electoral environments in Western Europe: the UK and the Netherlands. The UK comes closest to a two-party system in Western Europe; in both 1990 and 2017, the right was represented in parliament by the Conservative Party (although by 2017, the radical right did become a major electoral player). The Netherlands is a case of extreme proportionality, with several parties on the right.

If cross-pressured voters support the right in both countries and in both 1990 and 2017, then the asymmetric right-wing advantage is likely generalizable across different party system configurations. This is indeed the case: as shown in Appendix Table 12, combinations of conservative and progressive attitudes were likely to be resolved in favor of the right in these two very different electoral environments. It is especially relevant that this was the case in the United Kingdom in 1990, with no credible radical right parties. This should come as no surprise: the Conservatives' reliance on a segment of the working class, or the ‘Tory working man’, had been key to their electoral strategy since the early 20th century (Beer Reference Beer1965).

I report the results of three additional robustness checks in the Appendix. First, to address concerns that the results are driven by differences in the level of political interest across respondents, Appendix Table 13 shows that cross-pressures are also resolved in favor of the right after controlling for political interest. Second, another potential concern is that the results are driven by extreme cases of both higher and lower scores on the ΔEC scale. To address this issue, I constructed a truncated ΔEC scale for both 1990 and 2017, excluding 5 per cent of the observations at the extreme ends of the scale. The results of these analyses are again substantively similar, as shown in Appendix Table 14. Lastly, it may be that many respondents place themselves at the middle of the left–right scale because they lack knowledge of the scale. To address this concern, I re-ran the analyses reported above after excluding respondents who located themselves exactly at the center of the self-identification scale and the results are substantively similar (Appendix Table 15).

Discussion and Conclusions

This article demonstrated that there are many ways to be right: the right – more so than the left – attracts voters with diverse worldviews. Scholars have already shown that ‘the issue basis of left/right identification is fundamentally dynamic in nature’ (de Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee Reference de Vries, Hakhverdian and Lancee2013, 236): it changes over time as it absorbs new issues. The evidence presented above shows that the attitudinal basis of left/right identification is also fundamentally asymmetric in nature: while support for the left is common among voters with bundled progressive attitudes, it is enough to be conservative on one issue to turn right. This is in line with the expectation that different groups of voters prioritize different issue dimensions – which are also the issues on which they tend to be conservative (Shayo Reference Shayo2009).

The consistency of the right-wing advantage among cross-pressured voters over 25 years suggests that it is a stable feature of West European politics. However, the degree to which cross-pressured voters lean rightward likely varies across contexts. For instance, as shown above, welfare chauvinists have tended to turn right in both 1990 and 2017 – yet this right-wing advantaged increased over time. The right's advantage among cross-pressured voters may become more pronounced in certain political contexts than others (Stenner Reference Stenner2005). For instance, the degree of social prestige conferred on low-skilled occupations has likely decreased over time in ways that may make some welfare chauvinists even more reliant on their national and religious identities as a source of social standing, further pushing them to the right (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017; Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2020). Elite-level changes also likely play a role in political discourse: the greater salience of cultural issues across Western party systems may also shape the degree to which some cross-pressured voters prioritize cultural over economic issues. These issues await further research.

My analyses are not without limitations. Like other studies of cross-national over-time variations in mass attitudes (Malka, Lelkes and Soto Reference Malka, Lelkes and Soto2019), the evidence is correlational. In addition, I lack direct evidence of the underlying mechanism that I theorize nudges both welfare chauvinists and market cosmopolitans to the right. This limitation is shared with previous studies that focused on the political behavior of cross-pressured voters (Federico, Fisher and Deason Reference Federico, Fisher and Deason2017; Shayo Reference Shayo2009). While this issue could be potentially addressed with an experimental design, the thrust of this manuscript was to focus on long-term patterns in public opinion, an issue that could mostly be studied through survey data.

While prior studies have focused on the center-left, the analyses above shed light on the challenges and opportunities of center-right parties. The increased dimensionality of the ideological space is a double-edged sword for the center-right (van Kersbergen and Krouwel Reference van Kersbergen and Krouwel2008). An electorate with many cross-pressured voters benefits the right-wing bloc, in contrast to the view that the right's diversity is a source of weakness (Borg and Castles Reference Borg and Castles1981). Furthermore, center-right parties are better positioned than center-left parties to adapt to an ideological landscape of cross-pressures, considering the right-wing identification of cross-pressured voters. Yet within the right-leaning bloc, Christian Democratic parties, which have served as a major pillar of West European post-war party systems (Kalyvas and van Kersbergen Reference Kalyvas and van Kersbergen2010), do not appeal to cross-pressured voters. The full implications for the center-right may thus turn on the viability of parliamentary coalitions between the center-right and other parties on the right in general and the radical right in particular (Bale Reference Bale2003).

How are center-right parties likely to respond to their electoral struggles? As the share of consistently conservative voters shrinks and satisfying both the welfare chauvinists and market cosmopolitans simultaneously becomes harder (Odmalm and Bale Reference Odmalm and Bale2016), center-right parties may have to choose which cross-pressured voters they prioritize. Center-right parties may find themselves increasingly oscillating between welfare chauvinists and market cosmopolitans, or simply collapsing as these two groups of cross-pressured voters opt for other parties on the right. This, in turn, calls for further attention to patterns of electoral competition across different parties on the right.

Lastly, it is worth reflecting on points of tension and overlap between these findings and research in American politics. Scholars of American politics emphasize the degree to which the American right is ideologically more homogeneous than the left (Grossmann and Hopkins Reference Grossmann and Hopkins2016; Lelkes and Sniderman Reference Lelkes and Sniderman2016). This may seem inconsistent with the evidence described above regarding the ideological heterogeneity of the right in Western Europe, yet there is no necessary contradiction here. This is because prior research in US politics stresses the degree to which right-wing Americans identify as conservative (which may describe both ideological and social identities), while my focus has been on the diversity of belief systems within the right.

There are apparently many ways to be right in the United States as well: previous research shows that cross-pressures are indeed more common on the American right than the left (Ellis and Stimson Reference Ellis and Stimson2012). Explanations for this finding often point to unique features of American politics, such as Fox News or the role of religion in American society (Claassen, Tucker and Smith Reference Claassen, Tucker and Smith2015). Yet since the asymmetric right-wing advantage among cross-pressured voters is also evident in Western Europe, explanations that are unique to the American context are at best insufficient. Greater engagement between scholars of American and comparative politics is needed to fully understand the political behavior of cross-pressured voters.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/4HSUXH and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000228.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments, I thank James Adams, Matthew Bergman, Bart Bonikowski, Charlotte Cavaille, Volha Charnysh, Winston Chou, James Conran, Ruth Dassonneville, Matthias Dilling, Shai Dromi, Leslie Finger, Michael Hankinson, Eelco Harteveld, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez, Will Horne, Jeff Javed, Guy Mor, Jonathan Polk, Zeynep Somer-Topcu, Daniel Ziblatt, Roi Zur, and the BJPolS editors and reviewers. Torben Iversen, Steve Levitsky and Kathy Thelen provided valuable feedback on previous versions of this work. I owe special thanks to Peter Hall. ORCID: 0000-0002-0217-1204.