The Weberian definition of ‘power’ is ‘the chance of a man or of a number of men to realize their own will in a communal action even against the resistance of others who are participating in the action.’Footnote 1 An implicit assumption underlying this definition is that the content of one's ‘will’ is independent of one's perceived ability to realize it. This article questions this assumption by examining the effect of external political efficacy on the content of policy preferences.

Our main claim is that external political efficacy, namely, the belief that one has some real measure of influence on policy decisions by expressing one's positions publicly,Footnote 2 plays a role in determining the degree to which policy preferences are independent from, or consistent with, the fundamental values encapsulated within a dispositional ideological position. In contrast to Campbell et al.,Footnote 3 who ‘introduced political efficacy as one of several independent components of political engagement that predicted voter turnout but not voter preference’,Footnote 4 we suggest that when citizens believe that their personal political position can actually influence public policy, they feel more motivated to conform to their deep-rooted ideological beliefs. Thus, we expect that when external political efficacy is high, political ideology will have a much greater influence on concrete policy preferences than when political efficacy is low. The findings of two different empirical studies consistently support our hypothesis.

In the following section, we review the literature on moderators of the association between political ideology and policy preferences, the concept of political efficacy, and the psychological and political bases for the efficacy interaction hypothesis. The subsequent section presents and reports the findings of the two empirical studies. The first is a survey experiment conducted in Israel in 2010, and the second is an analysis of the 2002 wave of the European Social Survey. The final section summarizes and discusses the findings and their implications.

Moderators of the Political Ideology–Policy Preferences Association

Why is political ideology influential in shaping people's policy preferences in some cases and not in others? This question has attracted the attention of many social scientists since the early 1960s. Political ideology is understood as a relatively stable and coherent belief system regarding ‘the proper order of society and how it can be achieved’.Footnote 5 According to Jost, Federico and Napier, ideologies help individuals to interpret the world as it is, by ‘making assertions or assumptions about human nature, historical events, present realities, and future possibilities’.Footnote 6 Throughout the years, most political scientists have assumed that ideological beliefs constitute a prism through which people view the world and are assisted in discerning which specific policies are expected to improve their well-being and that of their group members. However, the relationship between ideology and policy choice has been found to be moderated by the availability of political information, and more recently, by motivational predispositions and processes.

One of the most noteworthy and controversial findings of modern public opinion research is that only a small portion of the public structures its attitudes towards various political issues in terms of underlying ideological predispositions.Footnote 7 This particular subset of the population has been found to include those who possess expertise and knowledge of the political sphere.Footnote 8 Indeed, the bulk of the scholarship in this field tends to depict the successful use of ideology as an informational problem. A central approach in this literature identifies political sophistication as the most important moderator of the relationship between political ideology and concrete policy preferences.Footnote 9 The sophistication–interaction theory of public opinion posits that a certain level of political knowledge and awareness is required in order to relate general ideological views to concrete issues. It follows that political beliefs of the highly sophisticated citizens rely more heavily on ideological values to constrain their issue preferences and that the uninformed cannot ground their attitudes in these general values.Footnote 10 These micro-level findings are also supported by a recent macro-level analysis according to which when partisan debate on an important issue receives extensive media coverage, partisanship systematically affects issue attitudes.Footnote 11 The results support Zaller's earlier presumption that when partisan elites debate an issue and news media cover it, partisan predispositions are activated in the minds of citizens and subsequently constrain their policy preferences.Footnote 12

Conversely, Goren suggests the domain-specific approach that ‘posits that everyone holds and uses abstract principles relevant to a given policy domain to constrain their policy preferences with that domain’.Footnote 13 He presents evidence that sophistication does not moderate the impact of domain-specific principles on policy preferences. Goren suggests that information processing demands of using domain-specific principles are quite low, and citizens are more capable of principle-based reasoning than is typically recognized. However, while Goren's reliance on domain-specific principles rather than broader ideological ones (conservative–liberal) relaxes the informational demands of constraining policy preferences, its underlying mechanism and indeed the quality that sets it apart from the sophistication approach remains within an informational analysis of the policy polarization process.

Recent studies have pointed (either explicitly or implicitly) to motivational explanations of policy preference polarization. In line with the sophistication–interaction theory, Carsey and Laymen have shown that the availability of information on party differences on a particular issue is a condition of both party-induced issue preference updating and issue-induced partisan preference updating, which result in greater correspondence between the two attitudes.Footnote 14 However, they detect issue-based party conversion only for individuals for whom the issue is relatively salient, suggesting that at least part of the partisan polarization process is shaped by the motivation to hold a particular attitude.Footnote 15

Federico and Schneider demonstrate that though political expertise is positively associated with greater ideological constraint of policy preferences, this association is moderated by respondents’ ‘need to evaluate’ – ‘the extent to which an individual is motivated to spontaneously form evaluations of various social objects as either “good” or “bad”’.Footnote 16 This finding supports their theoretical claim, according to which ‘need to evaluate’ shapes information processing and storage, which then results in a greater association between ideology and policy preferences. Lastly, a different motivational mechanism – cognitive dissonance – has been demonstrated to account for opinion polarization, by economists Mullainathan and Washington.Footnote 17 They found greater polarization in presidential and senatorial opinion ratings for respondents who voted for/against the relevant candidates in the preceding elections. In this case, the motivational mechanism pertains to the drive for consistency between a person's past act (voting) and her expressed opinion.

Following the idea that preference polarization is shaped by motivational as well as informational processes, and relying on political and psychological processes, we introduce an additional individual-level motivational factor – external political efficacy – which has the potential to govern citizens’ relative freedom from, or adherence to dispositional ideological values when shaping opinions on specific policy issues.

Political efficacy: Basic conceptualization

A long-established conviction suggests that citizens’ subjective perceptions of personal effectiveness in politics, namely, their political efficacy, is one of the fundamental building blocks of any democratic regime.Footnote 18 The term political efficacy has its earliest roots in political science in the work of Campbell et al., who defined it as a feeling that individual political action does have, or can have, an impact upon the political process, meaning it is worthwhile to perform one's civic duties.Footnote 19 It is closely related to the broader psychological term of perceived self-efficacy, which reflects people's beliefs in their capability of exercising some measure of control over their own functioning and over environmental events.Footnote 20 In many ways, political efficacy can be defined as people's sense of control over their public and personal environments through acceptable political processes.

A general sense of political efficacy is composed of an integrated operation of two separate though related factors – internal and external efficacy.Footnote 21 Internal efficacy refers to beliefs regarding one's own competence to understand, judge and express one's political choices effectively. The external aspect of political efficacy concentrates on one's beliefs regarding the responsiveness of governmental authorities and institutions to citizen demands.Footnote 22 Cross-national studies have shown that the two concepts are not interchangeable, as they correspond to different dimensions of political activity.Footnote 23

Political efficacy encompasses beliefs regarding one's capacity to express individual preference by political action and the likelihood of this action to impact political outcome. One's perceived efficacy to convert preference into political action is covered by internal political efficacy, and the potential of one's action to impact political outcome is covered by external political efficacy. Indeed, this staged understanding of internal and external efficacy is supported by findings suggesting that internal and external political efficacy are positively correlated, with internal efficacy generally perceived as predicting external efficacy.Footnote 24 Our interest in this research is in the effect of one's belief in the likelihood of one's preference making a difference to the content of this preference. In this hypothesized process both internal and external efficacy may play a role, but external efficacy is likely to be empirically more useful in the sense that it captures the (perceived) ultimate effect of one's choice on political outcomes.

Political efficacy entails important consequences for political life. A lack of political efficacy can lead to political alienation and apathy, as well as a search for alternative ways to influence the political realm, not only through the legitimate political process. Therefore, a high sense of political efficacy is associated with high stability of democratic regimes mainly because it enhances citizens’ trust in the political system and the political process,Footnote 25 moderates levels of political alienation, and encourages citizens to take active roles in the political game above and beyond their formal democratic obligations.Footnote 26

The current study joins a renewed growing interest in political efficacy in the recent decade, by examining a different influence of political efficacy on the democratic process. It is suggested that perceived political efficacy affects the way people form their concrete positions on policy issues. More specifically, we suggest that external political efficacy positively influences the extent of people's reliance on political ideology in forming policy preferences.

The EFFICACY–Interaction hypothesis

Our hypothesis posits that higher levels of external political efficacy increase the congruence between people's policy preferences and their political ideology. This assumption is driven by two complementary explanations – a political explanation that we define as the efficacy–politicization circle explanation and a psychological explanation that is based on the classical cognitive dissonance theory.Footnote 27

According to the political explanation (the ‘efficacy–politicization circle’), once citizens believe they can actually influence the decisions made by politicians on a certain public issue, the issue then goes through a rapid politicization process. What follows is that the person's political identity becomes more salient and the issue that could have potentially been viewed from various perspectives, is now more likely to be viewed through the lens of one's ideological predisposition or partisan loyalties.Footnote 28 The politicization of the issue, coupled with the saliency of the political identity may lead to the polarization of public opinion on that issue.Footnote 29 Alternatively, in the absence of a feeling of external political efficacy, other identities (such as gender, family, ethnicity or profession) might play a more central role, and the issue is then viewed and analysed through other dominant perspectives, resulting in an aggregate de-polarization.

The politicization of an issue, driven by high perceived external political efficacy may also create the sense of a more competitive political setting. This perception of heightened competitiveness may result from the belief that if one has real influence on policy consequences, it would only be reasonable to assume that other citizens, with conflicting political positions, also possess such influence. Thus, the competitiveness between adversary parties or conflicting ideologies strengthens the commitment of each individual to her core beliefs, ideologies and party loyalties. In these cases the motivation to contribute to the desired political outcome within the general political game can override potentially conflicting motivations, driven by more personal worldviews or values. Preliminary empirical support for this idea can be found in the study of Hug and Sciarini on the role of partisanship in varying institutional arrangements of referendums on European integration.Footnote 30 They have found that in referendums with a binding outcome, government supporters strongly follow the position of the government, while in non-binding votes government supporters vote mainly on the issue at hand with diminished consideration of the government's position. Hug and Sciarini explain these results by suggesting that a binding referendum ‘forces the government supporters to link their vote on the treaty with almost some kind of “vote of confidence”’.Footnote 31

Alongside the political explanation, the hypothesized moderating role of political efficacy can be explained by an adjusted version of the classical cognitive dissonance theory.Footnote 32 Cognitive dissonance occurs when a person holds two cognitions (knowledge, beliefs or attitudes) that are inconsistent with each other. The inconsistency creates discomfort and subsequently a drive to reduce the dissonance. A later variant of cognitive dissonance theory maintains that the effects of dissonance are most clearly observed when there is an inconsistency between individuals’ actual behaviour and their perceptions of themselves on various aspects.Footnote 33

This elaboration of the theory appears to be particularly relevant to the main premise of the current research. As long as external political efficacy is low, expressing policy preferences that contradict a person's core political ideology do not really mean acting against that person's beliefs, but only expressing contradictory positions, which do not necessarily yield any practical implications. However, when external political efficacy is high, the implications of expressing positions that contradict a person's core political ideologies extend beyond the attitudinal dimension and into the behavioural one. Since dissonance theory suggests that it is easier for people to hold two contradictory beliefs than to act in a way that contradicts a core belief, it is expected that when external political efficacy is high, people will be motivated to reduce dissonance by adjusting their expressed policy preferences to complement their core dispositional political ideology.

Based on these political and psychological analyses, we hypothesized that external political efficacy moderates the effect of political ideology on citizens’ policy preferences. More specifically, we expect that the association between political ideology and concrete policy preference will be stronger when external political efficacy is high and weaker when it is low.Footnote 34

Empirical Analyses

In order to assess this hypothesis empirically, we conducted two empirical examinations that vary in nature (experimental v. observational) and context. The first (Study I) relies on an experimental survey among a nationwide sample in Israel (N = 600). The aim of the experiment was to test the causal effect of political efficacy on the relationship between political ideology and policy preferences. For this purpose we have used a novel experimental treatment to alter respondents’ external political efficacy, and examined its effect on the association between political ideology and a policy issue that was highly salient in Israeli public discourse at the time of the study – the negotiations between Israel and Hamas over a proposed release of Gilad Shalit (an Israeli soldier who was kidnapped on 25 June 2006 by Hamas in a cross-border raid) in exchange for the release of about 1,000 Palestinian prisoners held by Israel. The second (Study II), utilizes the 2002 wave of the European Social Survey (ESS), to test the hypothesized relationships between ideology, external political efficacy and policy preferences in twenty countries and regarding eight different concrete policy issues. The combination of these studies provides the complementing advantages of two research approaches: Study I enables strong internal validity by randomly assigning respondents to high/low political efficacy treatment groups, and a control group; Study II, by contrast, offers strong external validity, by drawing on a large, diverse and representative sample, and a variety of policy issues. Furthermore, Study II also enabled us to extend our framework by adding internal political efficacy to our analysis.

Study I

To test the causal relationship between external political efficacy, political ideology and support for concrete policies, we utilized a web-based experimental survey among a nationwide sample in Israel. The survey first assessed a number of relevant covariates. Next, respondents were randomly exposed to one of three treatments – low or high external political efficacy or control (no treatment) – after which they were asked about their policy preference on a salient public issue.

Our experimental manipulation relied on a novel external political efficacy treatment, aimed at making respondents believe that they could (or could not) influence actual policy on the issue in question later in the survey. The selected policy issue was the debate about whether Israel should release Palestinian prisoners, and if so how many, in exchange for the release of one captured Israeli soldier – Gilad Shalit – held by Hamas in Gaza. This affair had been a central issue in the Israeli public agenda.Footnote 35 Based on public statements of both Israeli and Palestinian officials at the time of the study, Israel and the Hamas were close to signing an agreement on a German-mediated prisoner exchange deal in which Hamas would release Shalit in exchange for Israel's release of about 1,000 Palestinian prisoners. The Israeli public was divided over this possible deal.

Importantly, Israelis were roughly divided on the question of the Shalit release bargain along their ideological positions on the right–left political spectrum. Traditionally, left-wingers in Israel (also defined as doves) express higher levels of support for compromises with Arab countries and with the Palestinians compared to right-wingers (also defined as hawks) who usually express uncompromising positions.Footnote 36

Method

Sample

Our experiment was embedded in a survey that was administered by the firm Midgam Project (MP) and fielded between 15 and 20 January 2010 to 1,565 panelists who were randomly drawn from the (MP) panel. Of these, 1,192 completed the questionnaire, yielding a final stage completion rate of 76 per cent. The MP is an opt-in panel that covers the Israeli population aged 17 years and older. The sample did not include Arab respondents (20 per cent of the Israeli population) since the Gilad Shalit affair involves aspects of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict on which Jews’ and Arabs’ attitudes systematically diverge.

Experimental manipulations

Respondents were randomly assigned to three groups of equal size. Each group was presented with one of the three versions of the survey questionnaire. The questionnaires began with a number of psychometric scales,Footnote 37 followed by the manipulation, and a series of questions regarding respondents’ opinion as to the Gilad Shalit release bargain. The manipulation section for the ‘high external political efficacy’ group included a vignette which informed the readers that political science research had shown that public opinion polls have a strong influence on government decisions in hostage release bargains (see Appendix 1 for the wording of the vignettes). The vignette in the ‘low external political efficacy’ group suggested that public opinion polls have no effect, and the control group received no vignette. Apart from the vignettes, the questionnaires were identical for the three groups. Thus, the actual difference between the content of the ‘high’ and ‘low’ external political efficacy versions is merely six words. Based on the results of a pilot study we conducted, we expected that, given that the subjects were taking part in a nationwide survey, the information regarding the actual effects of these kinds of surveys on policy makers would influence their sense of external political efficacy.Footnote 38

Since our manipulation relied on textual vignettes, the questionnaire included an instructional manipulation check (IMC).Footnote 39 The IMC is a single-item tool for detecting respondents who are not following textual instructions, or satisfice in reading and answering survey questions.Footnote 40 Following previous experimental studiesFootnote 41 recruitment continued until 600 respondents who had passed the IMC were collected (from the total 1192: 50.34%). The rest of the analyses were conducted with this sub-sample. It should be noted that the proportion of respondents who passed the IMC is not significantly related to the experimental groups (p = 0.538).

Measurements

Political ideology was assessed by using a single-item measure, in which respondents were asked to indicate their political position on a scale of 1 (extreme right) to 5 (extreme left). It is important to note that political ideology was measured separately from the experiment. Data on most of the respondents’ (N = 352) political ideology was provided by MP from its existing records, and in the remaining cases (N = 248) were fielded as a separate question two weeks after conducting the experiment.Footnote 42 This ensured that political ideology could not be influenced by the manipulation, and thus (unlike the ESS data) any change in the association between ideology and policy preference could be solely attributed to a change in policy preference rather than in ideology.

The dependent variable – support for a bargain in the Gilad Shalit case – was gauged by two items: (1) a choice between eight possible numbers of prisoners to be released in exchange for Shalit;Footnote 43 (2) a choice between seven levels of a Likert scale describing the extent of the respondent's support for the release of Shalit in exchange for about 1,000 prisoners. The two questions were highly correlated (r = 0.80, p < 0.001, Cronbach's α = 0.89), and were thus averaged into one variable – ‘deal policy’ – ranging from 0 (objection) to 1 (support).Footnote 44 This variable was found to have a bimodal distribution. For this reason, deal support was also transformed into a dummy variable that equalled 1 for deal policy values of more than the median (0.6), and 0 otherwise.

When participants had completed the questionnaires, they were told that the study was over, and they were fully debriefed about the goals and procedures of the study. Particular care was taken to explain that the vignette describing the extent to which public opinion polls influence leaders’ decisions on deals to free kidnapped soldiers was fictitious and that there was no final consensus in the scientific community about the actual influence public opinion has on decisions of that kind.

Sample statistics

For each respondent we measured a number of covariates which included gender, age and individual scores on self-efficacy and time-preference scales. Formal statistical tests show that the randomization procedure appears to have been successful. None of the covariates are significantly related to experimental group assignment, and their mean values are not significantly different across experimental groups. A test of the joint significance of the covariates in a multinomial logit model (predicting experimental group as a function of all the covariates shown in Table 1) has a p-value of 0.78. The sample characteristics are generally in line with those of the Israeli Jewish population.Footnote 45 The proportion of males and females (51.67 per cent) is not significantly different from that of the general Israeli Jewish population (50.91 per cent). The geographic distribution of respondents deviates from the true proportions in two out of seven regions (4 per cent overrepresentation of the Jerusalem region; and 3.4 per cent underrepresentation of the Tel Aviv region). Young people (17–39) are also overrepresented in the sample (by 7.3 percentage points). The median policy preference in the sample was for a release of 250–500 Palestinian prisoners in return for the release of Shalit, and the median score of 4 out of 7 in the scale of support for the release of 1,000 prisoners.

Table 1 OLS and Logistic Regression Analyses with the Level and Proportion of Support for the Release Bargain, Respectively

*, ** and *** denote one-tailed significance levels of 5%, 1% and 0.1%, respectively. † Extreme right = 1; extreme left = 5.

Results and Short Discussion

Manipulation check

In order to assess the effect of the manipulations on the three groups, we asked respondents to estimate the influence citizens have on political decision making on the issue of Gilad Shalit (Very little influence (1) … Very strong influence (7)). The results show statistically significant differences in respondents’ mean estimation of ‘citizens’ influence’ across the three groups, with the ‘high external political efficacy’ group ranking the highest (M = 5.08, SD = 1.740, N = 200), the control group with a middle value (M = 4.36, SD = 2.045, N = 202), and the ‘low external political efficacy’ group with the lowest (M = 3.18, SD = 1.840, N = 197). All pair-wise differences are statistically significant at p < 0.001. Importantly, more selective manipulation checks indicate no significant difference in the effect of the manipulation across right-wing and left-wing respondents.

Main analysis

Table 1 reports ordinary least squares (OLS) and logistic regression analyses with the level and proportion of support for the release bargain, respectively. For each analysis we begin with a bare-bones specification (Models 1 and 3). Models 2 and 4 add covariates for gender, age, self-efficacy and time preference. The primary focus of our analysis is on the interaction terms between political ideology and external political efficacy. In this study the latter variable is represented by two dummy variables representing experimental groups ‘high political efficacy’ (High PE) and ‘control’ (while the ‘low political efficacy’ group serves as the reference group), yielding two interaction terms High PE x Ideology and Control x Ideology, which indicate whether the association between political ideology and policy preference regarding the potential release bargain is significantly different from its value in the low political efficacy group. It is apparent from Table 1 that in all four analyses this variation is statistically significant when comparing the High PE and Low PE groups (p = 0.022 for the OLS estimate; p = 0.028 for the logistic estimate).Footnote 46 No significant difference in this association was found between the control group and the Low PE group. This finding thus appears to be robust for both measures of policy preference, and under different model specifications.

Figures 1 and 2 depict this effect graphically. Figure 1 depicts the OLS and Figure 2 the logistic marginal association between political ideology and deal policy, across the three experimental groups. Clearly, a positive association appears to exist between political ideology and the level of support for a deal in all three groups. This positive association suggests that people who identify themselves as more left-wing tend to support the release bargain. The important finding, however, is that the size of this association increases from the ‘low political efficacy’ group, through the control group, and up to the ‘high political efficacy’ group.Footnote 47 The treatment of external political efficacy in this experiment has produced the hypothesized effect suggesting that political efficacy moderates the association between political ideology and particular policy preferences by increasing these associations as political efficacy increases. While Study I provides support for our hypothesis, with strong internal validity, it leaves open the question whether this finding is limited to a particular policy issue, or national setting. Study II offers the necessary external validity by extending the research to eight different policy issues in twenty countries, drawing on data from the European Social Survey.

Fig. 1 Marginal association between ideology and support for Shalit bargain (OLS); 90% CI

Fig. 2 Marginal association between ideology and support for Shalit bargain (logit); 90% CI

Study II

If indeed external political efficacy moderates the effect of political ideology on policy preferences we should expect to find correlational indications of it above and beyond the specific context of the Israeli society. We thus rely on the 2002 wave of the European Social Survey (ESS; N = 42,359) to estimate the interaction between external political efficacy and political ideology in predicting eight policy preferences.Footnote 48

Method

Data and measurements

As indicated above, we utilize the 2002 wave of the ESS, which covers adults in twenty-two countries.Footnote 49 This wave of the ESS includes five questions that gauge political efficacy – three addressing internal efficacy, and two addressing external efficacy (‘Do you think that politicians in general care what people like you think?’; and ‘Would you say that politicians are just interested in getting people's votes rather than in people's opinions?’).Footnote 50 Valid responses were given on a scale between 1 (‘Hardly any politicians care what people like me think’) and 5 (‘Most politicians care what people like me think’). In line with the results of previous studies,Footnote 51 exploratory factor analysis on the five political efficacy items revealed two distinct factors which are divided between the external and internal political efficacy questions. The two questions measuring external political efficacy are moderately correlated (r = 0.6, p < 0.001, Cronbach's α = 0.75), and were summed into one variable representing external political efficacy, and adjusted to range between 0 and 8.

The measure of political ideology relied on the standard left–right self-placement scale (‘In politics people sometimes talk of “left” and “right”. Using this card, where would you place yourself on this scale, where 0 means the left and 10 means the right?’).

The 2002 ESS survey includes eight questions which capture people's preferences regarding various concrete policy issues. These questions are presented in Table 2. Three pairs of policy items were found to be associated, and thus were joined into three single policy-issue scales, and two policy items were analysed separately. This resulted in five policy issues for which preferences were analysed: immigration, socio-economic, anti-hate legislation, gay rights, and militant democracy.Footnote 52

Table 2 Policy Questions in the European Social Survey and Respective Policy Issues

Statistical Analysis

We can estimate the moderating effect of political efficacy on the association between a person's stable political ideology and her or his particular policy preference with the following regression equation:

Here Pij is the preference of individual j on policy i; Idj is the ideological position of j on the left–right axis; PolEfficacyj is the level of external political efficacy of j, and Controlsj is a vector of individual attributes. Our main concern is with the parameter of the interaction term involving Idj and PolEfficacyj. This parameter indicates whether the association between political ideology and a concrete policy preference varies across different values of political efficacy. More specifically, our hypothesis predicts marginal association between ideology and policy preference would be closest to zero under low political efficacy, and furthest from zero (in either the positive or negative domain) under high political efficacy.

Control Variables at the Micro Level

At the individual level in all models we have controlled for gender and age. Furthermore, given the consistent findings about the sophistication interaction that were described above,Footnote 53 this interaction and its components should be controlled for in any analysis. An increasing number of studies suggest that factual knowledge is the best single indicator of sophistication.Footnote 54 However, the ESS does not offer such measures. Therefore, in line with other studies we use respondents’ educational level as a proxy for political sophistication, and the model specification includes its interaction with political ideology.Footnote 55 In order to assess the robustness of the findings, we also conducted all the analyses using another proxy for sophistication – political news exposure – known to be strongly associated with political knowledge.Footnote 56

Control Variables at the Macro Level

Policy preferences can potentially be influenced by macro-level institutional variables. Controlling for such variables is particularly important when they are also related to the left–right ideology scale and to political efficacy. In order to address some of these institutional features, two sets of macro political variables were included in the analyses. Based on Piurko et al., two dummy variables representing collective public perceptions of the left–right ideological scale were included.Footnote 57 These categories include ‘post-communist’, ‘traditional’ and ‘liberal’ (as reference). Drawing on the work of Karp and Banducci, we also added two institutional variables that were found to be associated with external political efficacy: (1) ‘disproportionality’ between seats and votes; and (2) the number of coalition partners.Footnote 58 For the ‘disproportionality’ variable we rely on Karp and Banducci's figures, which are appropriate for the relevant ESS survey (2002).Footnote 59 Preliminary analyses of the overall relationship between ‘disproportionality’ and political efficacy in the ESS data suggested a non-linear relationship, thus a natural log (Ln) transformation of this variable was used in the analysis.Footnote 60

As shown in Table 2, responses to the policy questions are given on an ordinal scale. Therefore, the estimation of the parameters of Equation 1 utilized ordered-logit regression analyses. To account for the data structure in which randomizations were conducted within each country, the following analyses use robust clustered standard errors on the country-level and country-fixed effects:

$${ Logit({{P}_{ji}})\, = \,\, & {{\alpha }_{0i}}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{1i}}I{{d}_j}\,\times \,PolEfficac{{y}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{2i}}I{{d}_j}\,\times \,Educatio{{n}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{3i}}I{{d}_j} \cr &+ \,{{\alpha }_{4i}}PolEfficac{{y}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{5i}}Educatio{{n}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{6i}}Gende{{r}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{7i}}Ag{{e}_j} \cr & + \,{{\alpha }_{8i}}Traditional\, + \,{{\alpha }_{9i}}PostCommunist\, + \,{{\alpha }_{10i}}LnDisprop.\, \cr &+ \,{{\alpha }_{11i}}CoalitionSize + \,{{\alpha }_{12i}}Country\, + \,{{e}_{ij}}.$$

$${ Logit({{P}_{ji}})\, = \,\, & {{\alpha }_{0i}}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{1i}}I{{d}_j}\,\times \,PolEfficac{{y}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{2i}}I{{d}_j}\,\times \,Educatio{{n}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{3i}}I{{d}_j} \cr &+ \,{{\alpha }_{4i}}PolEfficac{{y}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{5i}}Educatio{{n}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{6i}}Gende{{r}_j}\, + \,{{\alpha }_{7i}}Ag{{e}_j} \cr & + \,{{\alpha }_{8i}}Traditional\, + \,{{\alpha }_{9i}}PostCommunist\, + \,{{\alpha }_{10i}}LnDisprop.\, \cr &+ \,{{\alpha }_{11i}}CoalitionSize + \,{{\alpha }_{12i}}Country\, + \,{{e}_{ij}}.$$

Results and Short Discussion

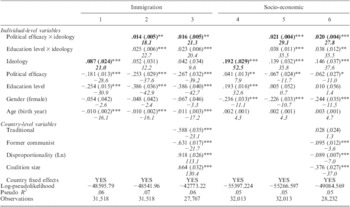

Tables 3, 4 and 5 present ordered logit regression results for the five policy issues preferences. For each policy preference we employ three model specifications. The first is a simple estimate of the associations between the main independent variables and the policy preference (Models 1, 4, 7, 10 and 13). These analyses present the overall association between ideology and each policy preference. The second model specification adds the interaction terms that involve external efficacy and ideology, and education level and ideology (Models 2, 5, 8, 11 and 14), and the third model specification adds country-level variables (Models 3, 6, 9, 12 and 15). All models include country-level fixed effects. As in Study I, the centre of the analysis is the interaction terms Political efficacy x Ideology which indicates whether the association between political ideology and the particular policy preference varies across the values of political efficacy.

Table 3 Ordered Logit Regression Estimates of the Moderating Effect of External Political Efficacy on Ideology–Policy Preferences Associations [Immigration and Socio-economic]

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance levels of 5, 1 and 0.1 per cent, respectively; robust clustered standard errors in parentheses, and percentage change in odds for one SD increase in the dependent variable is given in italics.

Table 4 Regression Estimates of the Moderating Effect of External Political Efficacy on Ideology–Policy Preferences Associations [Anti-Hate Legislation and Gay Rights]

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance levels of 5, 1 and 0.1 per cent, respectively; robust clustered standard errors in parentheses, and percentage change in odds for one SD increase in the dependent variable is given in italics.

Table 5 Regression Estimates of the Moderating Effect of External Political Efficacy on Ideology–Policy Preferences Association [Militant Democracy]

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance levels of 5, 1 and 0.1 per cent, respectively; robust clustered standard errors in parentheses, and percentage change in odds for one SD increase in the dependent variable is given in italics.

Tables 3 to 5 present the logit coefficient and standard error (in parentheses) for each relationship. Additionally, in order to offer a more substantively informative measure for these relationships, the percentage change in the odds for a higher rank in the dependent variable for one standard deviation increase in each dependent variable is presented beneath each coefficient in italics. All the policy preferences appear to have a significant association with ideology, except for militant democracy. The effect of one standard deviation increase shift to the right is associated with 21 per cent, 52.5 per cent, −15 per cent and 27.7 per cent changes in the odds of a higher level of opposing immigration, active social economic policy, supporting anti-hate legislation, and opposing gay rights policy, respectively (p < 0.001). Preference regarding militant democracy, however, was not found to be associated with ideology, with an insignificant 0.9 per cent change in the odds (p = 0.817). Given this latter null association, we do not expect to find a moderating effect of external political efficacy for this policy issue preference.Footnote 61

Next, Tables 3 and 4 show that nearly all the estimates of the Political efficacy x Ideology interaction terms are statistically significant in the hypothesized directions. This is evident by the finding that these interactions are positive where the policy preference is positively associated with ideology, and negative where this association is negative (support for anti-hate legislation). Only in Model 9 is the interaction term not statistically significant (p = 0.148). Another way to assess the substantively moderating effect of external political efficacy on the association between ideology and policy preference is by comparing the overall percentage change in odds of each policy preference associated with one standard deviation of shift to the right in ideology (presented in Models 1, 4, 7 and 10), and the conditional associational changes in odds presented in the same line in the other models for each policy issue preference. The conditional associations represent the change in odds when external political efficacy is minimal.Footnote 62 It is clear that in all the cases the latter associations are smaller than the overall associations: 9.6–12.2 per cent compared with 21 per cent for immigration policy; 35.5–37.6 per cent compared with 52.5 per cent for socio-economic policy; −11.6–−14.1 per cent compared with −15 per cent for anti-hate legislation; and 20.4–21.9 per cent compared with 27.7 per cent for gay rights policy.Footnote 63

These findings are consistent with our theoretical expectations. External political efficacy was found to increase the overall associations between ideology and each of the policy preferences. Where no overall association was found (in the case of militant democracy policy, see Table 5), no moderating effect of political efficacy was observed. Finally, in the case of anti-hate legislation policy, where overall association with ideology was relatively the weakest, the moderating effect of external political efficacy was statistically insignificant in one model specification (Model 9).Footnote 64

Assessing the Results under an Alternative Proxy for Political Sophistication

This section assesses the robustness of the findings of Study II by replacing education level with media exposure, as proxy for political sophistication. As noted above, since direct measures of political knowledge are not available in the ESS, we have used education level as a proxy for political sophistication. Another proxy that has been identified in the literature is media exposure, which is known to be strongly associated with political sophistication.Footnote 65 Relying on three items available in the ESS that reflect exposure to media coverage of political issues,Footnote 66 we created a joint measure and used it in the analyses (Cronbach's α = 0.53). Table 6 presents these findings, by presenting only the variables of theoretical interest. The findings are substantively similar to those of the main analyses. External political efficacy appears to increase the associations between ideology and all the policy preference. It should be noted that in this analysis this finding is statistically significant for all the model specifications for the anti-hate legislation policy. It should be, however, noted that the sophistication interaction was not replicated in these analyses (as it was with the education level proxy).

Table 6 Robustness Tests with Political Media Exposure as Proxy for Political Sophistication

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance levels of 5, 1 and 0.1 per cent, respectively; robust clustered standard errors in parentheses, and percentage change in odds for one SD increase in the dependent variable is given in italics. All models include controls for education, gender, age and country-level fixed effects; Models 18, 21, 24 and 27 add country-level controls for traditional, post-communist, Ln-proportionality and coalition size.

Extending the Findings beyond External Political Efficacy: The Moderating Role of Internal Political Efficacy

In this article our hypothesis was that external political efficacy may serve as a motivational moderator of policy preferences. However, since internal efficacy is akin to external efficacy, we take advantage of the inclusion of measures of internal political efficacy in the 2002 ESS (Cronbach's α = 0.61), in order to offer a more comprehensive examination of our theoretical framework. While external and internal efficacy are distinct attitudes, they are expected to play a cumulative role in shaping a person's overall sense of political efficacy.Footnote 67 Accordingly, in the context of this research we expect both external and internal efficacy similarly to moderate the ideology–policy preference association.

For this purpose, two additional sets of analyses were conducted. The first attempts to replicate the findings of Study II by replacing external with internal political efficacy. The second analysis utilizes one policy issue to assess the combined moderating effect of external and internal efficacy on the ideology–policy preference relationship, in order to demonstrate that these effects do not merely overlap, but rather add up cumulatively.

Results of the first set of analyses are presented in Table 7. These findings suggest that internal efficacy plays a similar role in moderating the relationships between political ideology and policy preferences as external political efficacy.Footnote 68 To address the goals of the second set of analysis, we estimated the ideology–policy preference association for socio-economic policy issues, restricting it to four different combinations of internal and external efficacy levels.Footnote 69 These are all possible combinations of low (below median) and high (above median) levels of internal and external efficacy. Table 8 shows that when both internal and external efficacy is low (top-left cell), the association between ideology and the policy preference is weakest.Footnote 70 Increasing only external (top-right cell) or internal efficacy (bottom-left cell) results in statistically significant increases (p < 0.001) in this association. These findings support the argument for a parallel effect of the two attitudes. However, the combined effect of high external and internal efficacy (bottom-right cell) indicates a further increase in this association, suggesting that external and internal efficacy have a cumulatively moderating effect on the ideology–policy preference relationship.Footnote 71

Table 7 Regression Estimates of the Moderating Effect of Internal Political Efficacy on Ideology–Policy Preferences Associations

Note: *, ** and *** denote significance levels of 5, 1 and 0.1 per cent, respectively; robust clustered standard errors in parentheses, and percentage change in odds for one SD increase in the dependent variable is given in italics. All models include controls for gender, age and country-level fixed effects; Models 30, 33, 36 and 39 add country-level controls for traditional, post-communist, Ln-proportionality and coalition size.

Table 8 Estimating the Moderating Effects of Internal and External Efficacy

Note: *** represents statistical significance at p < 0.001; the upper figure in each cell is the logged odds ratio coefficient for ideology; the middle figure is the estimated percentage change in odds for one SD rise in ideology (shift to the right); and the bottom figure is the number of respondents in each analysis. All four analyses control for the sophistication effect (education level as proxy), education level, gender, age, whether the country is traditional, former communist, logged disproportionality of parliament seats and votes, coalition size and country fixed effects.

The results of Study II provide additional support for our hypothesis. For four out of the five policy issues external political efficacy was found to increase the associations between political ideology and the policy preferences, and the null finding for the fifth policy issue is also in line with our theoretical expectation, as this policy preference did not exhibit an association with ideology. These findings were consistent across various policy issues, and model specifications. Moreover, Study II suggests that our hypothesis applies also to internal efficacy. Obviously, inferences drawn from the analyses of these cross-section data are exposed to the potential confounding associations between political efficacy and other factors. However, their consistency with our experimental finding provides credence to the possibility that these associations indeed represent causal relationships.

General Discussion

The main goal of the current research was to examine the role of external political efficacy in shaping policy preferences. Specifically, we sought to examine the moderating effect of external political efficacy on the association between political ideology and concrete policy preferences. Based on the integration of political (i.e., the efficacy–politicization circle) and psychological (i.e., cognitive dissonance theory) theoretical assumptions, we hypothesized that it would be easier for people to express a concrete policy preference that contradicts their long-term political ideology, when they do not really believe that their position on that issue would have actual political implications (i.e., low external political efficacy). By contrast, we hypothesized that when people truly believe that their expressed policy preference may influence real-life policies (i.e., high external political efficacy), they will try to avoid expressing positions that are incongruent with their ideology, and be motivated to reduce potential dissonance by adjusting their policy preferences to their ideological value set.

The two studies conducted provide support for this hypothesis. Study I allows us to infer causality from the change in the ideology–policy preference association between experimental groups. Moreover, given that ideology was measured separately from the experimental setting, the change in ideology–policy preference can be attributed solely to a change in policy preference. Such selective inference is not available in Study II, as the change in the association can result from a shift in either expressed ideology, or policy preference, or both. The combination of random assignment and the independent measurement of political ideology in Study I allows us an exceptionally clear interpretation of its findings: Enhanced external political efficacy increases peoples’ tendency to adjust their policy preferences to their held political ideology.

The results of the current research contain theoretical, methodological and practical implications. From a theoretical perspective, they broaden our understanding of the processes that govern the role of relatively stable political ideologies in shaping more transient policy preferences. Previous studies have concentrated on the role of political information in moderating these relations. These results add to those few relatively recent works that introduce motivational processes of ideological polarization. Following Federico and Schneider, we had expected motivation to play a role in ideological polarization of policy preferences.Footnote 72 Yet our current work links this motivation not to a personal predisposition, but rather to the way individuals perceive their role in a political environment – political efficacy – which draws on both enduring personal attributes and, importantly, transient or stable situational aspects.

In contrast to an established conviction, according to which no association exists between political efficacy and policy preferences,Footnote 73 our findings reveal that external political efficacy has an indirect effect on expressed policy preferences. While the overall effect of political efficacy may be null, the effect on each ideological group is substantive. Moreover, changes in political efficacy that differ across political groups may result in overall attitude shifts. To illustrate this point, drawing on our experimental data we can calculate what would have been the overall proportion of support for a hostage release bargain under varying conditions of external political efficacy allocation across ideological group, as shown in Table 9.Footnote 74 This analysis demonstrates that while a uniform change in external political efficacy across ideological groups (comparison on the principal diagonal) yields an insignificant shift of 4 percentage points in overall support for the policy in our sample (p = 0.44), changes in this political perception that are not uniform across ideological groups (comparison on the anti-diagonal) results in a significant difference of 13 percentage points in the overall level of support (p = 0.017).

Table 9 Overall Level of Support for a Bargain under Different Allocations of External Political Efficacy among Ideological Groups

This relationship introduces a range of implications for the study of ideological polarization by looking at the consequences of micro-level and macro-level antecedents of political efficacy for public opinion. The work of Hug and Sciarini can serve as such an example.Footnote 75 Drawing on the findings of this research, it is possible to account for their findings by a mediating (unmeasured) effect of the institutional setting (non-binding/binding referendum) on external political efficacy, and its consequent effect on vote polarization.

In addition to its theoretical contribution, these findings yield some applied implications that can be utilized by decision makers, political consultants and others who have an interest in mobilizing public support. According to the results, political efficacy can serve as a political tool that may free citizens’ choices from their ideological and party loyalties, or contribute to strengthening the adherence of choices to such value sets. It appears that a sensitive use of that tool can potentially be applied by politically interested parties to attract new potential supporters, or to secure the support of traditional constituencies.

From a methodological perspective, this is the first study, to the best of our knowledge, in which external political efficacy has been manipulated experimentally. Although some scholars have already acknowledged the differences between general and situation specific political efficacy,Footnote 76 most political scientists and political psychologists have treated political efficacy as a relatively stable individual characteristic.Footnote 77 The fact that external political efficacy can be manipulated by using such a small-scale intervention holds promise for future studies to be conducted in this field.

One limitation of Study I is that the manipulation used to boost external political efficacy is issue-specific.Footnote 78 This fact can potentially raise doubts about the generalizability of the findings to other policy domains as well as to other political contexts. Previous studies, however, have emphasized the importance of situation-specific and domain-specific feelings of political efficacy, by showing that the more specific the feelings of efficacy, the greater the predictability of political behaviour.Footnote 79 Yet we still believe that future studies should aspire to extend the findings of this study by manipulating external political efficacy on other domains, as well as by trying to manipulate a general sense of political efficacy, above and beyond one specific domain.

To conclude, our empirical findings support the existence of a moderating effect of external political efficacy on the degree to which policy preferences would be guided by enduring political ideology at the individual level. Our model was driven by an integration of political and psychological theories, yet this research merely provides support for the outcome of these hypothetical mechanisms. In our view, identifying and untangling these mechanisms is probably the main challenge for future studies.

Appendix 1: Wording OF VIGNETTES

‘Low External Political Efficacy’

One of the most interesting and important questions addressed by political scientists in recent years is to what extent public opinion polls influence leaders’ decisions on political issues in general and on deals to free kidnapped soldiers and civilians in particular. Prof. Herbert Ross of Yale University in the United States conducted the most extensive study to address this question and came up with clear and fascinating results. Prof.Ross and his team examined how public opinion polls have influenced leaders’ decision-making in negotiations to free captives in 179 cases in 20 different countries, including Israel. They found that public opinion polls have no influence whatsoever on the decisions made by the leaders regarding the price they were willing to pay to return the captive or captives home. Specifically, in 155 of the 179 cases the leader actions did not correspond with public positions, as these were presented to him or her in public opinion polls. Furthermore, Ross, who examined Israeli public attitudes regarding deals to free captives and conducted in-depth interviews with leaders who made decisions on such deals, claims that in Israel, the relationship between public opinion polls and leaders’ decision-making is significantly weaker than that found in all other countries studied in [his] research. In other words, public opinion polls’ influence over the decisions of Israeli leaders is insignificant, and the Israeli public thus has no power or influence on whether such deals do or do not go through.

‘High External Political Efficacy’

One of the most interesting and important questions addressed by political scientists in recent years is to what extent public opinion polls influence leaders’ decisions on political issues in general and on deals to free kidnapped soldiers and civilians in particular. Prof. Herbert Ross of Yale University in the U.S. conducted the most extensive study to address this question and came up with clear and fascinating results. Prof. Ross and his team examined how public opinion polls have influenced leaders’ decision-making in negotiations to free captives in 179 cases in 20 different countries, including Israel. They found that public opinion polls have tremendous influence on the decisions made by the leaders regarding the price they are willing to pay to return the captive or captives home. Specifically, in 155 of the 179 cases the leader actions corresponded with public positions, as these were presented to him or her in public opinion polls. Furthermore, Prof. Ross, who examined Israeli public attitudes regarding deals to free captives and conducted in-depth interviews with leaders who made decisions on such deals, claims that ‘In Israel, the relationship between public opinion polls and leaders’ decision-making is significantly stronger than that found in all other countries studied in his research. In other words, public opinion polls’ influence over the decisions of Israeli leaders is substantial, and the Israeli public thus has great power and influence on whether such deals do or do not go through’.