For years, Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) have inspired political scientists to study the party political sphere in terms of structural conflicts between social groups as a consequence of distinct historical revolutions. They maintained that principal role of political parties was to give expression to these group conflicts. We argue that the predominance of neoliberal austerity and increasing ethno-cultural diversification in recent decades highlight the need for a new theoretical model to study the party political sphere. This model focuses on the way parties frame how social solidarity may be preserved.

While Lipset and Rokkan's cleavage theory has led to fruitful cross-national comparisons of European party systems (for example, Bartolini and Mair Reference Bartolini and Mair2007; Franklin, Mackie and Valen Reference Franklin, Mackie and Valen2009), many scholars associate two important problems with it (Enyedi Reference Enyedi2005; Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2012). First, in contemporary post-industrial societies group memberships are less static and more liquid than Lipset and Rokkan's perspective warrants (Bauman Reference Bauman2000; Ignazi Reference Ignazi2014). Self-identification is the outcome of an individual trajectory rather than a given. Hence, some contend that party de-alignment occurs where frozen cleavages are melting away and the linkage between party competition and the social structure is diminishing (for example, Dalton and Wattenberg Reference Dalton and Wattenberg2002). Secondly, political parties are not passive vessels expressing pre-established social divisions; they are also active evaluators and framers of social conflicts (Deegan-Krause and Enyedi Reference Deegan-Krause and Enyedi2010; Riker Reference Riker1986; Tavits and Potter Reference Tavits and Potter2015). As a consequence, others argue that we are currently witnessing a process of re-alignment in which new social conflicts either replace or become more important than old ones (for example, Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt1994).

Yet few researchers take into account that the individualized times of today coincide with revolutions of globalization and migration, which necessitates a different view of what constitutes the contemporary basis of the cleavages (for an interesting exception, see Bornschier Reference Bornschier2010). From their Parsonian structural–functionalist perspective, Lipset and Rokkan explicitly stress the conflict pole of the conflict–integration dialectic (1967, 5), according to which solidarity is relevant, but only to those who thought the working class needed better social protection (Spicker Reference Spicker2006). However, the current challenges are different: group categories have become more fluid, leaving the individual full of agency but in a structural wasteland. Hence, the crucial conflicts of today are about the best way to preserve social cohesion; thus solidarity has become everyone's concern.

Accordingly, the programmatic urge of parties that strive for political change will best be revealed in the conflicting solidarity frames they adopt to protect or enhance social cohesion. By framing and priming particular solidarities in their communication, political parties build a rhetoric that cuts across multiple issues and social groups. Yet, the role of party political agency in communicating and framing solidarity remains underdeveloped (Banting and Kymlicka Reference Banting and Kymlicka2017). While Baldwin (Reference Baldwin1990) and Stjernø (Reference Stjernø2005) have explored similar questions, they did so when solidarity was still an exclusive prerogative of leftist group thinking.

Our perspective encompasses more party families, including rightist populist parties that present themselves as ‘new champions of solidarity’ (Banting and Kymlicka Reference Banting and Kymlicka2017). This is important because the solidarity frames of new(er) political parties in particular might stimulate new party political struggles around solidarity (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018). Examples include conflicts between ‘welfare chauvinists’ (Schumacher and Van Kersbergen Reference Schumacher and Van Kersbergen2016) and cosmopolitans (Bauböck and Scholten Reference Bauböck and Scholten2016) or those between liberal nationalists (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka2015) and neo-liberal multiculturalists (Žižek Reference Žižek1997). However, these examples of the party politics of solidarity lack an overarching theoretical framework, not least because Lipset and Rokkan's traditional cleavage theory has paid limited attention to the factors that ‘bind individuals into collectives’ (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2018).

We fill this lacuna by adopting a Durkheimian perspective that fully appraises the dialectical aspect of the relationship between conflict and integration, but nevertheless takes the integrative component more seriously than, for instance, Lipset and Rokkan (Lukes Reference Lukes1977). Concretely, we use a recent dialectical adaptation of Durkheim's classical distinction between mechanical and organic solidarity (Thijssen Reference Thijssen2012; Thijssen Reference Thijssen2016). Because mechanical solidarity is not gradually replaced by organic solidarity, as Durkheim predicted, it makes sense to treat the different poles of mechanical and organic solidarity as fundamentally conflicting and capable of perfectly coexisting over time.

We test this Durkheimian solidarity framework using a deductive content analysis of Belgian (Flemish) party manifestos in 1995 and 2014. Yet because most industrialized societies will be confronted with similar structural challenges to solidarity at some point in their histories, we believe the results of our explorations will apply far beyond the Belgian context for three reasons. First, it makes sense to look at a fragmented party space in terms of the pervasiveness of different solidarity frames instead of the more traditional cleavage theory or more inductive spatial models. We find considerable variation across the two diagonal axes of the solidarity framework: group-based/empathic (GB-E-axis) and exchange-based/compassionate (EB-C axis). Secondly, the salience of the former increases over time in terms of a growing distance between parties that emphasize group-based solidarity frames (for example, welfare chauvinism of populist parties) and those that focus on empathic solidarity frames (for example, cosmopolitanism). Thirdly, in general, party positions on the latter EB-C axes converge on the exchange-based pole (neoliberal multiculturalism); social-democratic parties and greens are the only ones that strongly endorse compassionate solidarity frames. These evolutions are largely congruent with those specified by scholars focusing on the effects of policy shifts on the structuring of the party political sphere (for example, Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009).

Our article is structured as follows. First, we elaborate the Durkheimian framework in order to identify partisan solidarity frames and their evolution. Next, we discuss why the Flemish (Belgium) party system is a good test case for the framework and explain the modalities of our manifesto research. Finally, we present the results of our content analyses and discuss the implications for the structure of the party political sphere.

A Solidarity ‘Frame’-Work

How are societies held together in modern times? In De la division du travail social, Durkheim (Reference Durkheim2014 [1893]) distinguished between mechanical and organic solidarity. The former emphasizes the importance of a high degree of perceived similarity among group members, who identify themselves with a conscience collective that compels them to support their group members. They share a set of rights and duties, and are guarded and regulated by group pressure and norms – just like family members care about each other because they are family. Free-rider behaviour is a potential danger for mechanical solidarity. Therefore, free-riders and deviants deserve severe and effective punishments (Fararo and Doreian Reference Fararo, Doreian, Doreian and Fararo1998). Durkheim theorized that modernization processes and increasing specialization led to more differentiated societies characterized by organic solidarity. Individuals are now bound together by their differences in the sense that they are often complementary and create reciprocal interdependence. Contractual obligations strengthen the commitment to reciprocate. Ideal-typically, mechanical solidarity is present in primitive societies; however, it also survives in modern organic societies.

Many contemporary social scientists are reluctant to interpret reciprocal exchange as an integrative principle, especially when it is viewed as a capitalistic exchange. After all, the neoliberal zeitgeist of recent decades has led to welfare state retrenchment, which can hardly be seen as a manifestation of solidarity. As a consequence, neoliberalism is often defined as the negation of solidarity (for example, Kriesi Reference Kriesi2015). However, Hirschmann (Reference Hirschmann1977) has convincingly argued that this interpretation falsely equates a singular historical outcome (neoliberalism) with its underlying principle (the civilizing role of trade and material interests). Moreover, only by clearly differentiating group-based principles from exchange-based principles is it possible to clearly distinguish between their dialectical counterparts: compassionate and empathic solidarity frames. The former stresses the importance of commonality in difference, for example when one focuses on the common nationality of individuals who are socio-economically very different. The latter implies a valuable difference in commonality, for example when one acknowledges that not all nationals have the same capabilities. In other words, while the mechanical dialectic stresses the integrative principle of in-group and out-group bordering, the organic dialectic focuses on the integrative principle of mutual exchange, which might lead to in-change – a change in one's own moral sentiments.

Yet just like Lipset and Rokkan's cleavage theory, Durkheim's early solidarity theory has drawn criticism for its functionalism and structural focus: solidarity is a fait social, closely linked to macro-sociological indicators such as collective identity, division of labour, and the prevalence of either punitive or contractual law. In this respect, it makes sense to integrate some micro-sociological elements into Durkheim's macro-sociological framework and to treat solidarity as a socially constructed or ‘framed’ reality instead of a social fact sui generis. Moreover, because we will identify these frames in political parties’ manifestoes, solidarity generally takes the form of a behavioural intention – primarily policy proposals designed to affect social change, but sometimes also in terms of strengthening grassroots social capital.Footnote 1

To specify different solidarity frames, we use the integrative typology of Thijssen (Reference Thijssen2012), who seeks to bridge the gap between Durkheim's structural solidarity theory and contemporary intersubjective approaches such as Honneth's recognition theory (Reference Honneth1996). Thijssen argues that each of Durkheim's two solidarity types involves a dialectical process linking universal structural principles (forces of system integration) with particular intersubjective orientations (forces of social integration). Consequently, this typology explicitly scrutinizes the subjective impact of structural principles, such as collective identity and the division of labour, on rational reflections and emotive reactions such as compassion and empathy. While Lipset and Rokkan's Parsonian cleavage framework (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) mainly focused on in-group allegiance and especially how this generates conflict with particular out-groups, Thijssen's Durkheimian solidarity framework stresses (1) the integrative power of similarity as well as differences and (2) processes in which these integrative principles are evaluated in terms of marginal individuals.

The mechanical dialectic relies on an evaluation of the structural principle of the similarity of group members (group-based thesis) in terms of group members situated in the fringes (compassionate antithesis). The organic dialectic relies on the evaluation of the structural principle of the civilizing role of exchange between partners with complementary qualities (exchange-based thesis), in terms of individuals who are so different that they seem to have little to contribute (empathic antithesis). Due to the challenges of migration and globalization, advanced capitalist democracies are increasingly confronted with marginalized individuals with questionable qualities. Hence, evaluations of mechanical and organic solidarity have become more frequent and more urgent. In such circumstances, political parties tend to fall back on some kind of solidarity master frame that can be more inclusive or exclusive.

Welfare chauvinism (for example, De Koster, Achterberg and Van der Waal Reference De Koster, Achterberg and Van der Waal2013; Kitschelt and McGann Reference Kitschelt and McGann1995) is an example of a frame that involves a mechanical exclusive synthesis in the sense that the system of social protection is reserved exclusively for those who belong to the in-group. The in-group crucially derives its meaning from the negation of a certain out-group. For example, the welfare state takes care of the rights of those who are not immigrants or their descendants. Hence, immigrants are not only those on the outside; they define who is in: their pain is not ours, because they are fundamentally different from us, the in-group. Yet both Kymlicka's liberal nationalism (Reference Kymlicka2015) and Rorty's liberal compassion (Reference Rorty1989) are examples of mechanical inclusive syntheses that involve a dialectical process of coming to see other beings as ‘one of us’, which ‘requires a re-description of what we ourselves are like (our commonality)’ (Rorty Reference Rorty1989, xvi). The in-group thus gets its meaning from a dynamic identification process that accommodates the unfamiliar. Again, the trigger is to cope with the unpleasant encounter of the neediness of an out-group member who is situated on the fringes of the in-group. In sum, while exclusive mechanical syntheses frame solidarity as a structural group-based principle, inclusive mechanical syntheses frame solidarity as feelings of compassion.

Neoliberal multiculturalism (Bauböck and Scholten Reference Bauböck and Scholten2016) is an example of a frame that involves an organic exclusive synthesis that reserves the exchange system (trade) for those who are able to market themselves and to create meaningful inputs now or in the future. The proper exchange partners are defined by what a passive bystander does not contribute. Cosmopolitanism (Archibugi Reference Archibugi2008) and workshop democracy à la Sennett (2012) can, however, be seen as examples of organic inclusive syntheses that involve a process of coming to see other beings as a priori valuable by virtue of their otherness and by adapting and extending the understanding of what are considered proper exchange goods. In this sense, the exchange partner is redefined in terms of a more universal category. In sum, while exclusive organic syntheses frame solidarity as a structural exchange-based principle, inclusive organic syntheses are inclined to frame solidarity as feelings of intersubjective empathy.

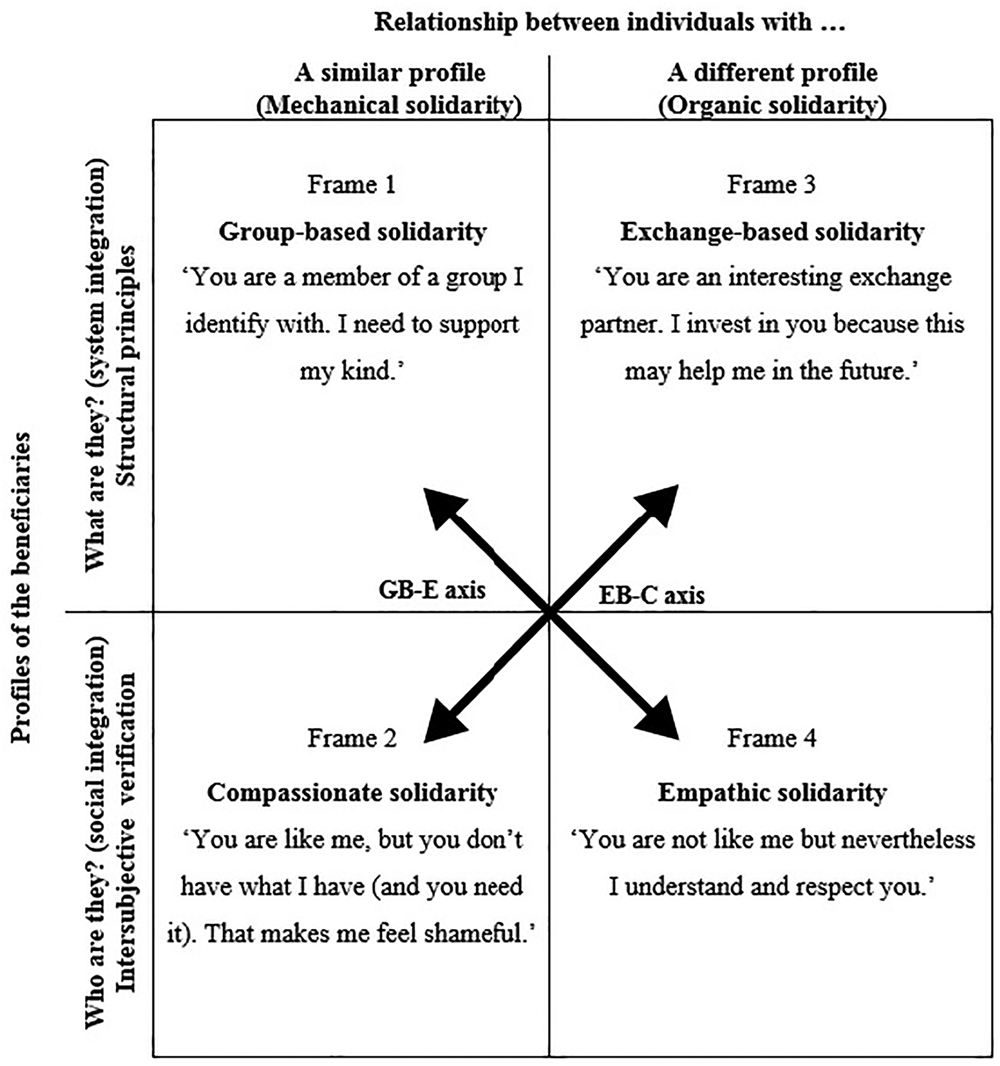

It seems logical that inclusive evaluations stand in a natural political conflict with exclusive evaluations. In this sense, both the mechanical and organic dialectic internally harbour some conflict potential. Nevertheless, the most intense party political conflicts are likely to be found across the diagonals because these solidarity frames are opposing in terms of both the principles of structural vs. social integration and homophily vs. heterophily (see Figure 1). On the one hand, group-based solidarity is based on a structural principle of similarity between the group members (they are members of my group), while empathic solidarity centres on the intersubjective valuation of difference (that person is different from me). On the other hand, exchange-based solidarity is built on the idea that society is a system that is organized around people with complementary differences that are in a relationship of serial reciprocity and interdependence (they are my exchange-partners), while compassionate solidarity follows from the encounter with people in a marginalized position and the intersubjective verification of these people as equals (that person should be in an equal position as I am). These diametrical oppositions are depicted by the diagonal arrows in Figure 1.

Figure 1. The four solidarity frames found in Thijssen (Reference Thijssen2012, Reference Thijssen2016) and the diagonal interrelations (added).

Hence, in line with Lipset and Rokkan who derive a two-dimensional space from Parsons–AGIL scheme, we expect that political parties can be ordered within a two-dimensional space generated by the two diagonals of ‘the double dichotomy’ (1967, 10). While one axis is grounded in the opposition of frames that stress the structural principle of similarity of group members and those that emphasize that everybody's contribution is valuable even if they are completely different from us (GB-E axis), the other is centred on the opposition between frames that stress the structural principle of the utility of complementary differences and those that highlight compassion for those who are dependent and vulnerable (EB-C axis).

Hypothesis 1

Parties can be differentiated in terms of the pervasiveness of different solidarity frames in their party manifestos based on two axes, GB-E and EB-C.

Obviously, parties will often experience pressures from different solidarity frames. Yet, we expect the way they deal with such pressures to depend on the same national (for example, changing electoral competition) and international factors (for example, neo-liberal austerity and growing ethnic and cultural diversity) that scholars have distinguished in studies on the effect of policy shifts on the structure of the party political sphere (Deegan-Krause and Enyedi Reference Deegan-Krause and Enyedi2010; De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012). More specifically, we expect that the current pressures of globalization and immigration might lead to partisan polarization on both the GB-E and EB-C axes.

In a globalizing context of neoliberal austerity, we expect economic and financial challenges to motivate parties to polarize along the EB-C axis. On the one hand, leftist parties (social democrats and greens) will assert a compassionate solidarity frame, as they wish to distance themselves from austerity measures while simultaneously remaining responsive to each other (Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009; De Vries and Solaz Reference De Vries and Solaz2019; Tavits and Potter Reference Tavits and Potter2015; van der Brug and van Spanje 2009). On the other hand, all other parties will find exchange-based solidarity frames attractive to win votes and remain responsive to shifts from ideologically close and relevant rivals (Adams and Somer-Topcu Reference Adams and Somer-Topcu2009). Consequently, this will make most non-leftist parties less distinctive from each other on the EB-C axis.

However, in a context of increasing ethnic and cultural diversity, all parties (especially those on the right) will have an incentive to polarize along the GB-E axis. In these circumstances, the radical right populist parties have an incentive to assert a group-based solidarity frame. This pressures other parties, especially those on the right, to either adopt a similarly group-based solidarity frame or to affirm the opposite – an empathic solidarity frame (Kriesi et al. Reference Kriesi2012; Schumacher and Van Kersbergen Reference Schumacher and Van Kersbergen2016).

Hypothesis 2

In a globalizing context of neoliberal austerity, polarization along the EB-C axis will increase, due to:

2a: the insistence of leftist parties (social democrats and greens) on compassionate (C-) frames; and

2b: the attractiveness of the exchange-based (EB-) frames for all other parties.

Hypothesis 3

In a context of growing ethnic and cultural diversity, polarization along the GB-E axis will increase, due to:

3a: the insistence of radical-right populist parties (Vlaams Blok/Belang) on group-based (GB-) frames; and

3b: the other parties either following or affirming the opposite empathic (E-) frames.

Cases, Data and Methods

We conduct a deductive content analysis of party manifestos, which are invaluable for mapping parties within a multidimensional space (see Franzmann and Kaiser Reference Franzmann and Kaiser2006). Although most voters do not read party manifestos, parties use them to provide narratives and defences of their policy choices (Smith and Smith Reference Smith and Smith2000) that are not so different from messages in other media (Hofferbert and Budge Reference Hofferbert and Budge1992). By analysing their manifestos, we can assess the pervasiveness of the different solidarity frames. The case in question is Flanders (Belgium), which has a fragmented multiparty system with a high effective number of parties. As parties (re)shape their master frames in response to strategic pressures resulting from (1) major changes in the sizes of their constituencies and government coalitions and (2) the occurrence of (inter)national challenges (Deegan-Krause and Enyedi Reference Deegan-Krause and Enyedi2010; De Vries and Hobolt Reference De Vries and Hobolt2012), we assume that between 1995 and 2014 Flanders has experienced important changes in both respects:

1. The federal election of 1995 was overshadowed by the fear of the further expansion of the radical right Vlaams Blok, which attracted more than 10 per cent of the Flemish votes in the preceding ‘Black Sunday’ national election of 1991. Nevertheless, the electoral expansion of the radical right was largely contained by the cordon sanitaire (Pauwels Reference Pauwels2011). Consequently, the Christian and Social Democrats could consolidate its governing coalition. The election of 2014 centred on whether the Flemish nationalist party N-VA could attract supporters of Vlaams Belang (the successor of Vlaams Blok), which lost eleven seats in the Flemish elections of 2009. The electoral power of the traditional parties has massively deteriorated, and they rightly feared that the N-VA would become essential in a new Flemish coalition.

2. The two main international structural challenges for advanced capitalist democracies over the last two decades have been globalization and migration (Beramendi et al. Reference Beramendi2015). Belgium, and especially Flanders, is fairly vulnerable in both respects, in recent decades it has had both one of the lowest shares of non-offshorable occupations and one of the highest shares of foreign-born population in the OECD (Dancygier and Walter Reference Dancygier, Walter, Beramendi, Häusermann, Kitschelt and Kriesi2015).

Typically, party manifesto research uses the popular codebook of the Manifesto Project, which provides codes for ‘civic mindedness’ or for referents such as ‘underprivileged minority groups’ (Lehmann et al. Reference Lehmann2017). Unfortunately, this coding is not specific enough for our purposes, since the kind of sentences they refer to are still rather heterogeneous and do not differentiate among various solidarity frames. Therefore, we develop our own method and codebook to distinguish solidarity in parties' discourses. Because one ‘cannot escape the interpretive nature of any study of ideology’ (Gerring Reference Gerring1998, 297–298), we primarily use a qualitative sentence-by-sentence approach to identify the solidarity frames. A dictionary-based automated coding, in which a computer allocates text units to an a priori or a posteriori defined coding scheme, proved unfeasible since solidarity frames cannot be linked unambiguously to a concise set of (combinations of) substantives, adjectives, adverbs and verbs (dissimilar from Laver, Benoit and Garry (Reference Laver, Benoit and Garry2003), who claimed feasibility). Only about 30 per cent of our qualitatively deduced corpus of sentences were recuperated in an automated coding procedure based on a list of keywords using Yoshikoder (Lowe, Reference Lowe2015). Nevertheless, the intersection proved to be useful for triangulation purposes and to find extra sentences with solidarity frames that were initially overlooked (see the Appendix).

In order to recognize a solidarity frame, a codebook with generic word combinations was used as a reference. We ensure the reliability of the findings by regularly discussing the content and validity of the coded sentences. Where there were disagreements, the authors reconsidered their theoretical assumptions and the codebook. This more reflexive, intersubjective and incremental procedure is regularly used in qualitative content analysis and is often used to increase the validity of the coding procedure.

In line with Thijssen's typology (see Figure 1), group-based solidarity frames refer to either a certain (desired) commonality and sense of togetherness (due to common interests and goals, shared values and norms, or common rights and duties) or to the fact that a perceived out-group is fundamentally different from the in-group. Secondly, we code compassionate solidarity if a party claims that a referent experiences risks, is a victim, or is marginalized and thus deserves help. Thirdly, we code exchange-based solidarity if a party refers to the usefulness of ‘exchange partners’ in terms of actual or future contributions or a willingness to contribute. These exchange partners are rewarded or stimulated but can also be demanded to contribute more in order to receive support. Finally, we code empathic solidarity when a party refers to diversity, being different or having a unique (set of) characteristic(s) as something to be respected and taken into account. Sentences praising the diversity of a larger in-group (for example, the nation) are also coded as manifestations of empathic solidarity, as such utterances show that ‘we’ are characterized by heterogeneity instead of homogeneity.

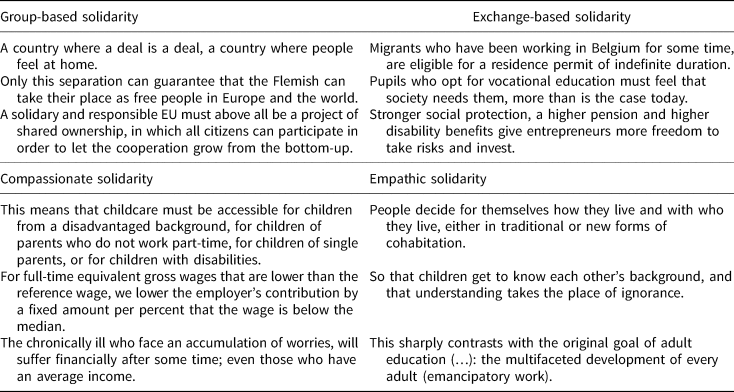

In Table 1, we provide more examples of each solidarity frame. To illustrate the relevance of the frames, these example sentences are linked to different policy domains, such as labour market policies, migration and asylum, and education. Nevertheless, there is an elective affinity between solidarity frames and policy domains: both group-based and empathic frames are often used with regards to identity issues, while compassionate and exchange-based frames are predominantly used for redistributive issues.

Table 1. Examples of coded sentences

We first coded entire party manifestos (that is, those of the Flemish elections of 2014).Footnote 2 In a second phase, we drew both random and stratified samples (per chapter) from these coded manifestos (n = ±1,000 sentences) and again calculated relative frequencies for each solidarity frame. We then tested whether the sample proportions are significantly different from population proportions using z-tests. We drew six samples for each partyFootnote 3 and calculated the percentages for 9 × 30 categories of solidarity frames. Ultimately, only 12 per cent of these scores were significantly different from the corresponding population proportions. Furthermore, we found no significant difference between proportions based on random sampling and those based on stratified sampling. We therefore decided to rely on random samples of approximately 1,000 sentences for the 1995 manifestos. The Appendix includes a list of the coded party manifestos, the number of sentences per sample and per population, and the number of sentences.

We assess the prevalence of solidarity frames within a party system and how they form the dimensions of this system. Therefore, we rely to a great extent on their relative frequencies, which are based on the absolute number of sentences with a specific solidarity frame divided by the total number of sentences with a solidarity frame in the manifesto. In this respect it is important to stress that the N-value in the denominator is not always equal. Hence, absolute frequencies are important too. For instance, if we found that party X used twenty-two sentences with a compassionate solidarity frame while in total 117 sentences contained one of the four solidarity frames, then the probability of compassionate solidarity would be 22/117 or 18.8 per cent. In order to reliably compare the probabilities for each of the solidarity frames across parties and to assess the dimensions of solidarity within the Flemish party system, we calculate interparty standardized probabilities (ISP) per solidarity mode to assess the distance between parties. For instance, if the probability of finding a solidarity frame in the manifesto of party X equals 18.8 per cent, its corresponding ISP would be equal to: (18.8 – mean percentage for compassionate solidarity across all parties)/standard deviation of the percentages for compassionate solidarity across all parties).

Finally, we test our assumption that the two most important oppositions underlying the dimensionality of the party system are the GB-E and EB-C axes. In order to assign party scores based on these dimensions, we subtract the ISPs of empathic from those of group-based solidarity, and those of compassionate from exchange-based solidarity. However, this approach assumes orthogonality of the dimensions, which might not be the case (see Marks and Steenbergen Reference Marks and Steenbergen2002 for a discussion and examples). In order to assess whether the Flemish party landscape can be organized in terms of two orthogonal solidarity dimensions that each reflect two diametrically opposed solidarity frames, we compare the plot resulting from our deductive approach with that of purely explorative correspondence analysis (see Beh Reference Beh2004). This method shares similarities with principal component analysis, as it inductively infers the underlying dimensions and positions of objects on these dimensions and displays them in a two-dimensional space. While the correspondence analysis uses the complete two-way contingency table with all ISPs and lets the data ‘speak for itself’, it provides little support in the assignment of meaning to the underlying dimensions, which is essentially left to the creativity of the researcher (see Greenacre Reference Greenacre1984 for a discussion of this topic). In that sense, the inductive correspondence method complements our deductive approach. Hence, a similar relative positioning of the parties in both the deductive plot and the inductive correspondence plot confirms our theoretical assumptions regarding the meaning of the dimensions.

Results

In this section, we discuss the results of our content analysis of Flemish party manifestos. First, we analyse the kind of solidarity frames parties tend to use in more depth based on a qualitative content analysis. Moreover, we investigate whether the prevalence of certain frames has changed over time, notably between 1995 and 2014. Secondly, in order to test the robustness of our qualitative findings we compare these results with a quantitative content analysis. Finally, we provide overview plots of the Flemish party competition in terms of the two diagonal axes.

Comparative Qualitative Analysis: Differential Manifestation of Solidarity Frames

First, in both 1995 and 2014, solidarity is predominantly framed in group-based terms in the party manifestos of the radical rightist (Vlaams Blok/Vlaams Belang) and nationalist parties (Volksunie/N-VA). Both sets of parties stress the merits of belonging to an in-group, for example by referring to the need for commonality; focusing on commonly shared values, interests and norms; downplaying internal differences; or explicitly denouncing any commonality with certain out-groups. For instance, the 2014 N-VA party manifesto states, ‘we find solidarity Footnote 4 and involvement in groups with which we can identify ourselves, in which we feel “at home”, find security and recognition’ (N-VA 2014, 34; emphasis added). Qua referent the in-group is typically the Flemish community, while the out-group generally refers to migrants or Muslims for the radical right and to French-speaking Belgians or Walloons in the case of Flemish nationalists (Volksunie 1995).

Other parties use the group-based frame as well, but generally refer to other in-groups such as the European community. Furthermore, when they mention migrants or Walloons they are not treated as an out-group but rather as people who could belong to the (Flemish) in-group. However, the liberal party Open VLD sometimes claims that people who do not agree with the core values of society do not belong in that society, encroaching on terrain of the radical rightist and conservative nationalist parties.

Secondly, solidarity is often framed as compassion in the manifestos of social democratic, green and Christian democratic parties. However, in 2014 this compassionate frame can be linked more exclusively to the party manifesto of the Social Democrat Party (sp.a 2014). The compassionate frame is often invoked by references to the worsening living conditions of the most vulnerable people and to a commitment to help them. For example, the Flemish Social Democrats (SP) manifesto states: ‘In the fight against lack of occupancy and slums, the municipalities must be able to count on even more support from the Flemish government: ranging from subsidies to the right of pre-emption, claiming and expropriation in favour of the most vulnerable families’ (SP 1995).

Compassionate solidarity typically refers to a wide range of people or groups, such as the social democratic claim that ‘many people find it difficult to find their way in this complicated society, encompassing older people, people with a disability, single-parent families, single people, migrants, children that suffer the consequences of pollution and asylum seekers that need humanitarian care’ (SP 1995).

Despite this leftist dominance in compassionate framing, other parties also commit themselves to alleviating the living conditions of the poor and weak. However, they typically focus on referents who are held less responsible for their condition and are higher on the deservingness ladder (van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2006) such as people with a disability. For instance, the liberal party VLD claims that ‘policies for people with a disability should focus on the integration of the disabled’ (VLD 1995, 11).

Thirdly, solidarity is predominantly framed in an exchange-based fashion in the manifestos of the liberal party. However, this seems to be less the case in the most recent manifestos. The Flemish nationalists and Christian democrats demonstrate a strong commitment to this solidarity frame in 2014 as well. Broadly speaking, they are in favour of a more active society with more people who contribute. As the Flemish nationalists stated in their 2014 manifesto, social welfare ‘is only possible if we encourage and reward the people who create prosperity through work and entrepreneurship, instead of discouraging and punishing them’ (N-VA 2014, 4, emphasis added). In positive terms, they wish to support those who are active and to revalue contributors, such as entrepreneurs or teachers (e.g. CD&V 2014, 76). In negative terms, we find that manifestos often imply that the unemployed should reciprocate and contribute more. Activation would benefit the unemployed as well as society as a whole. In other party manifestos, exchange-based frames do not constitute a core element and often refer to different referents than the typical occupational groups. For instance, some parties positively invoke exchange-based solidarity with migrants, whose skills or knowledge can be useful, or negatively with ‘polluters’, who should pay for polluting the environment, akin to the contractual obligations found in Durkheim's organic solidarity.

Finally, solidarity is prevalently framed in an empathic way among the green and social democratic parties in 1995 and to lesser extent the Christian Democratic Party (CVP 1995). In 2014, the greens and social democrats still used this solidarity frame, yet were overtaken by the liberal party Open VLD. These parties perceive individual or intergroup diversity in a positive way, as something that should blossom through acceptance, tolerance and (mutual) accommodation. For example, the Greens claim: ‘We want a colourful society in which everyone can be himself’ (Agalev 1995, 6). The right to be different is manifested in statements supporting the unicity of certain groups or individuals such as LGBT+, the elderly and people with a disability. However, other referents such as the young are empathically framed, as exemplified in the liberal support for the unique talents and interests of pupils expressed in Open VLD's 2014 manifesto (Open VLD 2014, 21) and in the Green's claim to let them be themselves and to let them be young (Groen 2014, 222). Empathic solidarity is uncommon in radical rightist party manifestos; a rare example is their appeal for respect towards people with a disability (Vlaams Blok 1995).

Comparative Quantitative Analysis: Differences in Relative Frequencies of Codes

Our qualitative analysis provides a few indicative answers regarding our research questions. First of all, different parties frame solidarity differently. Secondly, some shifts seem to have occurred between 1995 and 2014: an empathic turn in the case of the liberal party and an exchange-based turn in the case of the Flemish nationalist and Christian democratic parties. We test whether we can validate these findings quantitatively. Furthermore, we will establish whether it makes sense to treat some solidarity frames as complementary categories, notably those on the diagonals of Figure 1.

We show the absolute and relative frequencies of the sentences containing a particular solidarity frame, in terms of all the sentences as well as their relative frequencies compared to the total number of sentences with a solidarity frame per party manifesto. We cannot but notice that statements rarely contain a solidarity frame: on average, about 15 per cent of all sentences in a party manifesto have a solidarity frame. We often coded relatively more sentences as containing a solidarity frame in shorter party manifestos, such as that of Vlaams Belang in 2014, than in longer party, such as the extraordinarily long party manifesto of Groen in 2014.

The results in Tables 2 and 3 indicate two conclusions. First, in both elections, one can differentiate parties in terms of pervasive solidarity frames. Nevertheless, between both elections three general shifts occurred. In 1995, group-based solidarity pervades Flemish nationalists’ and radical rightists’ discourses; compassionate solidarity pervades Christian democratic discourse; exchange-based solidarity pervades liberal discourse; and empathic solidarity pervades green and social democratic discourses. In 2014, exchange-based solidarity frames became more popular across the party landscape, as the conservative Flemish nationalist N-VA and the Christian-Democratic CD&V were in an equal position with the liberal party Open VLD. Furthermore, the social democratic party sp.a and the green party Groen became much more focused on compassionate solidarity and obtained a lower score for empathic solidarity. Finally, group-based solidarity pervades the radical rightist Vlaams Belang significantly more than for any other party, except for the conservative nationalists N-VA.

Table 2. Solidarity frames per party during the elections of 1995

Note: relative frequencies per solidarity frame are based on the relative proportion of particular solidarity frame within the total number of sentences with a solidarity frame in the party manifesto. Relative frequencies of total solidarity frames are based on the relative proportion of solidarity frames within the total number of sentences in a party manifesto.

a 2 standard deviations higher than minimum.

b 2 standard deviations lower than maximum.

Table 3. Solidarity frames per party during the elections of 2014

Note: relative frequencies per solidarity frame are based on the relative proportion of particular solidarity frame within the total number of sentences with a solidarity frame in the party manifesto. Relative frequencies of total solidarity frames are based on the relative proportion of solidarity frames within the total number of sentences in a party manifesto.

a 2 standard deviations higher than minimum.

b 2 standard deviations lower than maximum.

Secondly, we can conclude that in both 1995 and 2014, solidarity frame proportions are related. The relative proportions of group- and exchange-based solidarity are largely inversely proportional to the relative frequencies for compassionate and empathic solidarity, respectively, which corresponds to the diagonal arrows in Figure 1. However, we must also conclude that the GB-E axis became more salient than the EB-C axis between 1995 and 2014. The standard deviations for both group-based and empathic solidarity increased in 2014, but not for exchange-based or compassionate solidarity. In fact, the standard deviation for exchange-based solidarity decreased during this period. An analysis of the correlations in Table 4 shows that between 1995 and 2014 the negative correlation on the GB-E and EB-C axes increased, yet became significantly higher in absolute terms on the former than on the latter.

Table 4. Correlations between solidarity frames per election year

Comparative Plot Analysis: Comparing Deductive and Inductive Approaches

The negative correlations between relative frequencies for group-based and empathic solidarity, on the one hand, and between relative frequencies for exchange-based and compassionate solidarity, on the other hand, somewhat support our theoretical assumptions. Hence, it is sensible to depict the competition in the Flemish party system in terms of the diagonal relationships in Figure 1. We use the ISPs to visualize the parties' positions within this two-dimensional space. We subtract the ISPs for compassionate solidarity from those for exchange-based solidarity to obtain their position on one axis: positive scores indicate a preference for exchange-based solidarity, negative scores a preference for compassionate solidarity and null scores no preference. Similarly, we reconstruct the other dimension of solidarity by subtracting the ISP for empathic solidarity from the ISP for group-based solidarity: positive scores indicate a preference for group-based solidarity, negative scores a preference for empathic solidarity and null scores no preference.

As argued in the methodological section, we recognize that this approach a priori determines the meaning of the orthogonal dimensions in terms of the diagonals of our typology. To test the validity of these assumptions, we compare the deductive solidarity plots with a purely exploratory plot based on a correspondence analysis of the ISPs.

The deductive plot for the 1995 manifestos (see left pane of Figure 2) depicts a party system that is relatively fragmented along the two dimensions of solidarity, with outspoken parties found on either side of the dimension. We can effectively speak of two dimensions on which party contestation within the Flemish region takes place: a group-based/empathic solidarity axis and an exchange-based/compassionate solidarity axis. A comparison with the exploratory correspondence plot (right pane) nuances the conclusions of the confirmatory plot by indicating that there is no perfect orthogonality and that the strongly exchange-based position of the liberal VLD is not as outspoken as inferred by the ISP plot. The overall structure of the party landscape, however, remains largely the same.

Figure 2. Dimensions of solidarity in Flemish region (1995), based on ISP (left) and correspondence plots (right)

Note: Vlaams Blok = radical rightist; Volksunie = nationalist; VLD = liberal; CVP = Christian democrat; SP = social democrat; Agalev = green.

The deductive plot for the 2014 manifestos (left pane of Figure 3) shows that a double polarization took place in the Flemish party landscape between 1995 and 2014. First, the leftist parties sp.a and Groen position themselves as mainly compassionate contenders, while the other parties place themselves on the exchange-based pole of the axis, which confirms Hypothesis 2a. Secondly, the rightist parties are spread out along the GB-E axis, with Vlaams Belang as the main contender on the group-based pole and Open VLD the main contender on the empathic pole. The deductive plot shows that the distances on both axes are not equal, with a more pronounced polarization on the GB-E axis. A comparison with the correspondence plot (right pane) indicates that we make a valid inference regarding the dimensions and the overall positioning of parties on these dimensions, although the correspondence plot shows more convergence on the exchange-based and compassionate dimension than the ISP plot does. Due to the negative correlation between compassionate and group-based solidarity and the convergence on the exchange-based/compassionate axis, the Flemish party landscape is mainly divided into group-based solidarity parties and parties with other solidarity frames (see Figure 3).

Figure 3. Dimensions of solidarity in the Flemish region (2014); based on ISP (left) and correspondence plots (right)

Note: Vlaams Belang = radical rightist; N-VA = nationalist; Open VLD = liberal; CD&V = Christian democrat; sp.a = social democrat; Groen = green.

Robustness Check

As we explicitly focused on solidarity frames that are applicable across different groups of beneficiaries (solidarity referents), it is possible that we ignored the existence of correlations between solidarity frames and specific solidarity referents. Therefore, we conducted a robustness check of our results by eliminating all the sentences with particular solidarity referents and comparing these results with the original results. For this test, we chose (1) migrants and (2) health-related groups (the elderly, sick, people with disabilities and patients) for all parties, and (3) the Flemish people as referents specifically for the Flemish nationalist parties. We conducted two extra analyses: a chi-square test for differences in distribution and a comparison of ISPs for differences in positions. Although a chi-square test shows some significant differences between the distributions before and after elimination, the ISPs indicate that the party positions remain the same.

Discussion and Conclusion

Globalization, individualization and migration are simultaneously challenging social solidarity between different people and groups. Hence, many argue that it is of the utmost importance to consolidate social solidarity. There is, however, little consensus on how to reach this. Recent social theory argues that most strategies put identity, exchange, compassion or empathy forward. In this respect solidarity is becoming a kind of ‘super issue’ on which parties will display their programmatic stance and that structures their political conflicts. Still, the role of party political agency in communicating and framing solidarity remains underdeveloped.

To an important extent this lacuna may be explained by the tendency to look at the political sphere in terms of structural conflicts among social groups. After all, Lipset and Rokkan focused on the conflict pole of the conflict–integration dialectic (1967, 5). Integration was only of secondary importance, a by-product of identifying with some social groups and opposing others. Yet the ‘frozen’ social group basis is now disappearing. As a consequence, political parties may focus more on what binds people together than on what divides them. We therefore focused on the role that political parties play in framing social solidarity by systematically linking those frames to distinctive Durkheimian integrative principles, which cut across issues and groups. We believe it makes sense to study the structure of a party's political sphere based on the solidarity frames it uses in its party manifesto. Obviously, parties will often be cross-pressured between different solidarity frames. Yet, we expected that the way parties deal with such pressures will depend on the same national (for example, changing electoral competition) and international factors (for example, neo-liberal austerity and growing ethno-cultural diversity) scholars have identified in studying the effect of policy shifts on the structure of the party political sphere.

Based on our findings for Flanders (Belgium), we first confirmed that solidarity frames are indeed useful markers of distinctive partisan discourses and ideologies: group-based solidarity is mainly championed by radical rightist and nationalist parties; compassionate solidarity is strongly advocated by greens and social and Christian democrats; exchange-based solidarity is defended by liberals, Christian democrats and conservative nationalists; and empathic solidarity is promoted by the greens, liberals and to lesser extent social and Christian democrats. Hence, we can conclude that solidarity is no longer a prerogative of the left, in the sense that parties on the right also adopt solidarity frames that are obviously distinct from leftist frames.

With regards to partisan political opposition, we furthermore established that group-based frames generally do not go together with empathic frames (downward diagonal of our typology) and exchange-based frames do not go together with compassionate frames (upward diagonal of our typology). Those who value difference are less inclined to seek assimilation, and vice versa; those who have compassion for the weak are less inclined to see reciprocity as a fundamental principle of society, and vice versa. Our findings correspond to some extent with the results of expert surveys and party elite surveys (see Kriesi Reference Kriesi2010), as the inverse elective affinities between exchange-based and compassionate solidarity to a certain degree reflect the social–economic cleavage, and the socio-cultural cleavage reflects the inverse elective affinities between group-based and empathic solidarity. Given that our deductive approach is fundamentally different, this finding points to the concurrent validity of the underlying dimensionality.

Furthermore, between 1995 and 2014 the polarization on both diagonals increased. In other words, the opposition between parties emphasizing solidarity as group homogeneity and as recognition of differences was spatially more polarizing in the Flemish party system in 2014 than in 1995. The opposition of parties emphasizing compassionate and exchange-based solidarity was also still important, albeit less pronounced than for the GB-E axis. While the latter opposition is more similar to the classical gulf between socialists (equality) and liberalists (liberty), the former revolves around the gulf that divides those supporting either a bridging or a bonding form of the French revolutionary creed: fraternity. While the political struggle around compassionate and exchange-based solidarity underlying the socio-economic cleavage has become more technical (see also Mouffe Reference Mouffe2005), the choice between bonding with those who are similar and bridging the gulf with those who are different has become the most pressing question within contemporary democracies.

Further research should confirm whether this trend persists. First, we explicitly focused on solidarity frames that are applicable across different groups of beneficiaries (solidarity referents), while there might be a strong correlation between solidarity frames and specific solidarity referents. Future research could shed more light on the relationship between the frame-based and referent-based approaches. Nevertheless, a robustness test in which we removed sentences that explicitly referred to the Flemish as an in-group did not significantly alter the dimensionality findings, which provides some support for the usefulness of solidarity frames across referents.

Secondly, our study focused on party manifestos and did not take other forms of party communication into account. Future research should establish the extent to which our findings are also relevant with regards to speeches, communiqués and interviews in the media as well as social media posts. Indeed, Hofferbert and Budge (Reference Hofferbert and Budge1992) have noticed important similarities and consistencies in the messages of political parties across media.

Thirdly, further research should assess whether our findings are confirmed in other settings with a less fragmented party system. For instance, do we find a similar configuration in systems without a radical right party? Do we find more polarized party positions in a bipolar system? Moreover, it would be interesting to see whether the same oppositions can be found in different welfare state systems.

Fourthly, while we relied on a top-down deductive analysis of party communication (the supply side of the politics of solidarity), it would be interesting to assess whether a bottom-up analysis of public preferences (the demand side) would give similar results (see De Vries and Marks Reference De Vries and Marks2012). Furthermore, we could use either an inductive or a deductive bottom-up approach. In the latter case one can assess whether the dominant solidarity frames in the manifestos are also endorsed by their own party electorates, and to what extent they have an effect on their electoral choice.

Finally, our research focused on the solidarity frames used in party manifestos during elections. However, political actors may be less inclined to use solidarity frames in policy-making processes. Also in this respect it would be interesting to ascertain whether parties institutionalize these solidarity frames when drafting laws or making coalition agreements.

In sum, while further research is definitely necessary, our analyses have nevertheless established that it makes sense to use solidarity frames as a fundamental heuristic to understand partisan competition. It is worth studying the party political landscape from a deductive sociological point of view, as Lipset and Rokkan (Reference Lipset, Rokkan, Lipset and Rokkan1967) demonstrated more than fifty years ago, but perhaps without adopting their structuralist focus on conflicting social groups. In the end, however, our configurations do not look very different from those of the more popular inductive approaches, which indicates that we are looking at the same political reality.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/SMRBPN and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000137.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Jorg Kustermans, Kees Van Kersbergen, Wim Van Oorschot, the colleagues from the M2P-research group, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and suggestions.