The globalized economy of recent decades has seen flows of capital, people and goods, and institutions regulating these movements. With such mobility, there are concerns that gains from global governance and a more efficient allocation of resources are offset by lower accountability to national governments and reduced welfare provision, labor standards and human rights. Foreign direct investment (FDI) is a key economic flow in the global economy, and investor rights have been strongly protected since the 1960s by a large number of bilateral investment treaties (BITs).Footnote 1 Some view BITs as a development tool, arguing that they reduce risk, and thus channel much-needed capital to poor countries.Footnote 2 Indeed, recent evidence shows that countries signing more BITs see a greater inflow of FDI.Footnote 3 Yet others fear that the favorable treatment that BITs give foreign investors threatens the welfare and rights of various, less powerful, domestic constituencies.Footnote 4 Such concerns arise because, in contrast to strong investor protection, very few, if any, BITs mention labor or human rights.Footnote 5 These potential negative externalities of the ‘broad and asymmetrical rights’Footnote 6 granted through BITs have received little attention. We investigate whether BITs influence developing countries’ human rights practices.

The bulk of developing countries sign bilateral investment treaties to attract foreign investment, and do so primarily because of competitive pressures.Footnote 7 Recent work shows that host states may not have fully anticipated the constraining effects of investment treaties,Footnote 8 and have recently started to push back against BIT constraints on domestic policy.Footnote 9 Human rights groups have directly charged that investment treaties tie the hands of capital-importing developing countries, generating important grievances and worsening governments’ human rights practices. For example, the UK–Colombia BIT was signed in 2010 but was only ratified in 2014. Human rights and anti-poverty groupsFootnote 10 have argued that this BIT exposes the Colombian Government to costly lawsuits and impacts land reform programs. Similarly, non-governmental organizations (NGOs)Footnote 11 have reservations about the ongoing negotiations on a US–India BIT, including about how the investor–state dispute mechanism undermines the domestic policy space and justice system.Footnote 12

We contend that BITs contribute to a worsening of human rights practices. BITs lock in legally enforceable conditions that are attractive to investors while constraining states’ development and welfare policies. With BITs in place, it is costly for states to reverse such policies in response to likely popular grievances and, in some countries, repression becomes relatively attractive. More specifically, the lock-in effect of BITs incentivizes governments to favor foreign investors even at the cost of violating the rights of their own citizens. Retrospectively, many developing countries compete for investment and trade on issues ranging from environmental regulations to labor standards and welfare spending, and tend to be destinations for vertical investment seeking cost efficiencies. In addition, BIT provisions constrain future policies, from taxation to the provision of welfare benefits or basic infrastructure. Locked-in standards and constrained policy choices have fiscal and labor relations consequences, and are sources of popular grievances. The literature on the causes of repression suggests that states often respond with human rights violations to the manifested (or anticipated) protests that can result from these grievances. Yet, the same literature argues that rights violations are the result of a cost–benefit calculation vis-à-vis other non-violent options, and the globalization literature shows that races to the bottom are not necessarily straightforward responses, even in developing countries. We therefore argue that regime type moderates states’ reactions to potential dissent and the negative human rights consequences of BITs.

We test our theory on a sample of 113 developing countries from 1981 to 2009. Our baseline measure of human rights practices is based on the CIRI dataFootnote 13 and includes extra-judicial killings, disappearances, political imprisonment and torture. We find that countries ratifying more BITs have worse human rights practices, and show that the effect of the cumulative number of ratified BITs is conditional on the political regime: BITs are more likely to result in human rights violations in non-democracies. Our results are robust to instrumental variable techniques, the inclusion of a large number of control variables, the exclusion of outliers, variations in sample size, alternative measures of human rights violations and coding BIT-specific clausesFootnote 14 or focusing only on North–South BITs that likely govern de facto investment flows.

Our theory also suggests causal paths that can link BITs to human rights practices. We test whether BITs limit governments’ ability to tax and spend, and contribute to a worsening of labor relations, as well as social mobilization. We find that BITs depress de facto labor practices with no mediating effect of democracy, and reduce both fiscal spending and revenue, a negative effect that is smaller in democracies. Our theoretical expectation is that governments respond to both observed and expected social mobilization. We test the effect of BITs on measurable, observed political dissent, and several of our empirical models show that their effect is mediated by political regime: BITs increase dissent, but not in democracies. Finally, BITs do not solely operate indirectly through the posited causal mechanisms, but also directly influence states’ human rights practices.

The article makes several contributions. We are the first to systematically theorize and test the effect of the global investment regime on states’ human rights practices. Frail domestic institutions and low credibility with investors can be a motivation to join international treaties, including BITs. Yet the evidence in favor of a credible commitment rationale for BITs is weak for variables ranging from political institutions (democracy or political constraints) to economic risk (property rights or law and order) (Table 1). Specifically, there is no consistent evidence that countries with bad human rights records sign or ratify more BITs for credibility reasons.Footnote 15 Our work, however, shows robust evidence of an effect running from BITs to human rights violations, including evidence of plausible causal pathways. This research thus contributes to recent work on the effect of international economic treatiesFootnote 16 and international organizationsFootnote 17 on states’ human rights practices. It also backs calls to re-establish more space for states to act on economic and social policy and protect the rights of domestic constituencies.Footnote 18 Finally, states may have ratified BITs within a bounded rationality framework, without being fully aware of their implications for domestic economic and social policies.Footnote 19 Yet it appears that host states come to better understand their BIT commitments and protect investor rights, even at the cost of violating the rights of their domestic populations.

Table 1 Evidence that Host Countries With Low Credibility Sign BITs (Credibility Argument)

The article proceeds as follows. We first elaborate on the legal protections that BITs provide to investors. We then explain how BITs may affect human rights practices and derive two hypotheses. Data and research design are discussed next, followed by our empirical findings and conclusions.

BITs: INVESTOR RIGHTS VS. LACK OF PROTECTION FOR DOMESTIC CONSTITUENCIES

In the absence of multilateral institutions, BITs have been the most visible and powerful legal instruments governing the global growth of FDI. These treaties offer strong protection to foreign investors, while human rights provisions in BITs are marginal, at best.

Direct investment in a foreign country implies sunk costs, and BITs are designed to address concerns about the future behavior of host states.Footnote 20 Common policy reversals that have adverse impacts on investors include expropriation and discriminatory changes to performance requirements, capital taxation and regulation, tariffs and social contributions. BITs aim to guarantee investor protection, including through compensation for expropriation and fair and equitable treatment, or most favored nation treatment. They also allow investors to enforce their rights in a timely manner: Early BITs provided investor protections through state-to-state dispute resolution. More recent BITs grant foreign investors the right to adjudicate alleged violations of rights in international tribunals, without the need to exhaust local remedies, and, in case of non-compliance with arbitration decisions, broad rights to confiscate the host government’s property from around the world.Footnote 21

By the late 1980s, most BITs included such dispute settlement mechanisms and between 1990 and 2012 there were at least 564 international arbitrations against at least 110 host states.Footnote 22 These investor claims are directly related to the number of ratified BITsFootnote 23 and have important consequences. A first implication is for host states’ budgets. Monetary awards have been significant, as shown by decisions against the Czech Republic ($350 million in 2001), Lebanon ($266 million in 2005) and Ecuador ($2.3 billion in 2012).Footnote 24 Secondly, FDI decreases when investors allege violation of their rights even at the moment of filing of an international arbitration.Footnote 25 Thirdly, because arbitration is a high-risk, high-cost option, the mere threat of arbitration from investors can be effective in extracting concessions. Several examples of such threats have emerged, and experts estimate that the practice is not uncommon, even if it remains mostly confidential.Footnote 26 Also, host states may be disadvantaged compared to investors because many developing states have limited legal capacity to counter the BIT-driven investor–state claims. Evidence from litigations indeed shows legal asymmetry favoring foreign investors.Footnote 27

In contrast to strong investor protection, very few (if any) BITs mention human rights or associated fields,Footnote 28 and developing countries would like to see more BIT obligations for investors.Footnote 29 For instance, no explicit reference to human rights is included in the country model BIT of Germany (2008), France (2006) or the United States (2004). An exception is the 2007 the Norwegian model BIT, which mentions human rights in its preamble. However, such preambular language is too weak to compel compliance from either foreign investors or host states. Related provisions (labor or environmental standards) are increasingly mentioned in recent BITs or BIT templates.Footnote 30 This, however, is still far from the ‘hard’ language seen in Preferential Trade Agreements (PTAs), which explicitly link material benefits to compliance with human rights standards.

The following section leverages the strong protection offered by BITs to investors against the lack of provisions in these treaties with regards to human rights. Hafner-BurtonFootnote 31 forcefully argues that ‘change in repressive behavior almost always requires legally binding obligations that are enforceable’. We apply this logic in reverse to suggest that BIT - sanctioned binding legal commitments can incentivize the government to favor foreign investors (over vulnerable domestic populations), with a net result of worsening human rights practices.

BITs AND HUMAN RIGHTS

BITs include provisions that guarantee investor rights as well as mechanisms to legally enforce such provisions.Footnote 32 In brief, we argue that since many developing countries predominantly attract vertical FDI and compete for investment and trade, BITs lock in the initial conditions favorable to investors.Footnote 33 BITs also constrain states’ future development policy choices, from the provision of basic infrastructure to land reform. The overt favoring of foreign investors and the constraints on development policies are sources of popular grievance in host states, which can lead to outright protest or an anticipation of dissent. Repression and human rights violations are key responses of states to manifested or anticipated threats. Yet since states’ reactions to threats and economic globalization depend on domestic institutions, we suggest that regime type likely moderates the negative human rights consequences of BITs.

Developing Countries and Policies Favoring Investors

Many developing countries continue to compete in trade or for foreign investment by offering cost-cutting low taxes and lax labor standards, or reducing welfare spending. First, there are specific issues on which countries engage in ‘races to the bottom’ to attract foreign investment. For example, both rich and developing countries mirror peer behavior and compete for FDI by relaxing de facto labor practicesFootnote 34 or employment protection and regulatory standards.Footnote 35 Similarly, Klemm and ParysFootnote 36 show that developing countries compete on corporate income tax rates, as well as by offering corporate income tax holidays.

Secondly, the nature of developing countries’ integration into the global economy provides broad evidence of the existence of competitive pressures to offer favorable treatment to investors. Our theory fits best with flows of vertical FDI,Footnote 37 as this type of investment is particularly interested in conditions that cut production costs and, indeed, much of the investment in developing countries is vertical. Thus, work examining country characteristics (market size, quality and quantity of labor, location, tax rates) to infer the nature of investment concludes that developing countries attract vertical FDI.Footnote 38 A similar conclusion is reached by UNCTAD (2004), which shows that for both manufactured goods and services, FDI in developing countries is increasingly vertical. In addition, Buthe and MilnerFootnote 39 find that trade flows and FDI are complements, indirectly supporting their expectation that, at least for developing countries, FDI is largely vertical – part of intra-firm, cross-border transactions.

Thirdly, the link between investment in developing countries and their trade has further implications because BITs can lock in export-promoting policies. Multi-national corporations use developing countries as part of their global production chain by importing inputs and exporting processed goods.Footnote 40 Because developing countries serve as export platforms for multi-national corporations,Footnote 41 export-promoting policies are very attractive to foreign direct investors. Moreover, under certain conditions, trade competition leads to lower environmental and labor standards,Footnote 42 and trade competition induced by network position similarityFootnote 43 induces a convergence of countries’ fiscal and regulatory policies.Footnote 44

In addition to locking in past investor-friendly policies, BITs constrain governments’ choices for sustainable development and welfare improvement. Rudra,Footnote 45 for example, finds that exposure to globalization (trade openness and capital flows) lowers welfare spending in countries where labor enjoys little bargaining power. There are also numerous anecdotes that support the loss of sovereignty due to BITs. BlakeFootnote 46 argues that Denmark’s subsidies to local firms to develop environmentally friendly technologies contravene BIT national treatment clauses. In an another example, in 2007, investors from Luxembourg and Italy brought an International Centre for Settlement of Investment Disputes (ICSID) claim against South Africa arguing that the 2002 Mining and Petroleum Resources Development Act expropriated them because it required mining companies to be partly owned by the historically disadvantaged. After the claim’s settlement in 2010, South Africa ended its BITs with Belgium and Luxembourg, arguing that they limited the government’s transformative agenda. Additionally, there are pending BIT arbitrations arising from disputes over the provision of water and sewage services such as Aguas del Tunari vs. BoliviaFootnote 47 or Suez Corporation vs. Argentina.Footnote 48 Also, an increasing number of requests for the annulment of arbitration awardsFootnote 49 are argued by host states in relation to development and the provision of basic utilities – water, gas, electric power and infrastructure.Footnote 50

BIT Clauses Constrain Governments’ Policy Space

Several BIT provisions lock in initial conditions and constrain governments’ choices. One important standard in BITs is the national treatment clause, which prohibits host governments from making negative differentiations between national and foreign investors.Footnote 51 Under this clause, for instance, host governments may not favor domestic firms that match their policy goals, or require foreign investors to use domestic inputs, or locate in underdeveloped regions. A related BIT standard is the fair and equitable treatment clause, which is included in most BITs and can be applied to broader instances of state arbitrary or discriminatory behavior. This clause allows a potentially expansive interpretation of fairness and has been used successfully by investors against host states.Footnote 52

With direct nationalization on the decline, BIT clauses related to indirect expropriation have become prevalent. Besides guarding against weak property rights enforcement, indirect expropriation refers to less clear-cut and potentially very broad measures such as changes in taxation, revocation of licenses or denial of access to infrastructure. The vast majority of BITs include language referring to indirect expropriation and uncertainty over the scope of this clause has the potential to deter states from taking actions that, while in the public interest, may be regarded as indirect expropriation and requite significant investor compensation.Footnote 53

The inclusion of stabilization clauses in investment contracts also restricts domestic policy autonomy.Footnote 54 Such clauses aim to prevent host states from changing domestic law to the detriment of the investor, and to reassure foreign investors in projects that demand a large amount of investment, especially in infrastructure or natural resource exploration. About 40 per cent of BITs include umbrella clauses that allow investors to invoke the stabilization clause from contracts with the host state and proceed directly to international arbitration.Footnote 55

BITs, Grievance and Human Rights Violations

All things equal, the lock-in effect of BITs can force a government to favor multi-national corporations or foreign investors even at the cost of violating the rights of their own citizens. First, BIT provisions can simply ask the government to directly intervene and physically protect multi-national companies’ investment. Secondly, the same conditions that were designed to be favorable to investors and attract multi-national corporations have the potential to create popular dissent or the expectation of dissent, followed by government repressive counters.

Very directly, a common BIT obligation is to provide foreign investors with ‘full protection and security’. This clause commits host states to exercise ‘due diligence’ in protecting foreign assets and can be invoked by foreign investors when they encounter protests in host countries. In a recent arbitration case,Footnote 56 for example, a Spanish corporation sued Mexico for failing to uphold the full protection and security clause by claiming that the authorities did not act quickly to ‘prevent or put an end to the adverse social demonstrations’ around the investors’ hazardous waste treatment facility.Footnote 57 The arbitration tribunal dismissed the claim related to the Spain–Mexico BIT’s ‘full protection and security’ clause. Yet, it concluded that the government had to compensate the company on grounds of ‘indirect expropriation’ because, following popular protests, the government refused to renew the Spanish company’s permit to operate the landfill.

Secondly, BIT clauses preserve the incentives offered to attract investors. The consequence is limits on governments’ ability to tax and spend, as well as provide welfare and basic infrastructure development. In addition, governments have no incentives to improve labor law; instead, they are motivated to undermine labor standards by slacking on the implementation of labor law and reducing the de facto collective action capabilities of labor groups. Such locked-in conditions can create enormous dissatisfaction or straight out disapproval in the form of protest. In turn, the government’s response to popular grievance may turn violent or abusive.Footnote 58 For example, in 1997 there were peaceful protests in India against the social and environmental consequences of a power plant built by the Dabhol power company, a joint venture of three US multinationals. The protests were met with harassment, arbitrary arrest and preventive detention.Footnote 59

The grievances that result from policies favoring investors can lead to overt social mobilization or expectations of future dissent on the part of governments. Dissent in the form of protest (or the expectation of dissent as a consequence of popular grievances) increases the perceived threat for governments seeking to preserve the status quo, and may motivate them to employ repressive measures. Empirically, actual protest or potential dissent are key determinants of states’ use of coercive measures against their own citizens.Footnote 60

The use of state repression in response to manifested or anticipated dissent is the result of authorities’ assessment of the costs and benefits of rights violations versus other tools at their disposal.Footnote 61 Repression is thus not an automatic response. We explore the variation in the costs of repression in the next subsection. Here we argue that, ceteris paribus, when the government’s hands are tied by BITs, it becomes relatively expensive to address the root causes of popular grievance by taking measures against the legally protected investors. In addition, not only are investors’ rights legally protected, but these rights severely limit some of the non-repressive options that governments normally use to buy off the potential opposition, including increasing social benefits, cheap access to infrastructure services like water or electricity, or providing side payments through domestic companies. Our first hypothesis follows this discussion.

Hypothesis 1: BITs are associated with a worsening of human rights practices.

The Mitigating Effect of Political Regime

We emphasize the key point of the repression literature that rights violations are the result of a cost–benefit analysis, and therefore that domestic conditions can mitigate host states’ incentives to use repression. We focus on democracies, because democratic institutions are a key consistent variable that raises the cost of human rights violations.Footnote 62

In addition, democracies filter the effect of globalization. Races to the bottom are thus not necessarily a straightforward response: domestic institutions condition the effect of globalization on states’ welfare policy, labor standards or pension reform.Footnote 63 Democracies may also be less likely to offer favorable initial conditions to foreign investors. Thus Li finds that countries with better rule of law, which tend to be democracies, offer lower levels of tax incentives.Footnote 64 Also, favorable trade policies are valued by investors who use developing countries as export platforms, and Cao and PrakashFootnote 65 find that countries with low political constraints, which tend to be non-democracies, respond to trade pressures with lower standards for air pollution.

Moreover, while BITs tie the hands of all governments in a similar fashion, we argue that democracies and dictatorships vary in two key dimensions that affect states’ calculus of the costs and benefits of repression. First, democratic leaders and dictators are likely to have different assessments of the level of threat to their rule posed by popular grievance and dissent. All else equal, the greater the perceived threat to their rule, the more likely governments are to use repression.Footnote 66 It is likely, however, that the level of perceived threat emerging from conflict between the interests of multi-national corporations and domestic groups is higher in dictatorships. Protests or mass demonstrations, either manifested or expected, are more likely to be seen as challenges to regimes that severely limit citizens’ voting rights or freedom of speech and association as outlets to express grievance.

Secondly, democracies and dictatorships face different levels of accountability. In their review of the literature, Davenport and Armstrong note that ‘in democracies political leaders who use repression against their citizens can be removed from office through the popular vote and […] these governments contain numerous institutional checks and balances on government activity’.Footnote 67 Thus in political regimes that face real political opposition and a free media, episodes of human rights abuses can be expected to be quickly and widely acknowledged, raising the political and electoral costs of repression. In democracies, both mechanisms – a low threat perception and high accountability – are likely to balance the favorable treatment that BITs afford to investors with a high cost of repression. We therefore propose a second hypothesis.

Hypothesis 2: The negative impact of BITs on governments’ respect for human rights is mitigated in democracies.

DATA, MEASUREMENT AND RESEARCH DESIGN

We test our hypotheses using data for 113 developing countries from 1981 to 2009.Footnote 68 The start year is dictated by the availability of the key dependent variable. The sample includes only developing countries, because rich countries have a different position in the global economy and are both sources of FDI and FDI recipients. Human rights practices also tend to be better in rich countries, making it likely that the causal process and government trade-offs are different in the developing world.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable is the Cingranelli and RichardsFootnote 69 measure of government respect for physical integrity rights (CIRI updated to 2012). The CIRI data explicitly captures governments’ human rights practices, while other data only captures overall human rights conditions.Footnote 70 CIRI codes the violation of four physical integrity rights: the use of torture, disappearance, extrajudicial killing and political imprisonment. Our variable is an index ranging from 0 (no respect for any of the four physical integrity rights) to 8 (full respect for all four physical integrity rights), coded based on Amnesty International’s Annual Report and the US State Department’s annual Country Reports on Human Rights Practices. The index sums the coding for each of the four physical integrity rights, where 0 denotes frequent violations (fifty or more), 1 codes some violations (one to forty-nine) and 2 signals no violations. In our sample the most frequent violation of rights is torture, followed by incidences of political imprisonment. About 90 per cent of the sample experiences some or frequent violations of rights in the form of torture, and 70 per cent of the sample country-years experience some or frequent instances of political imprisonment.

Independent Variables

To test Hypothesis 1 we use the total cumulative number of BITs ratified by a country in a given year, because we focus on the total leverage that foreign investor interests may exercise over the host states through BITs. The more BITs a host state ratifies, the greater the potential for popular grievance and repressive government tactics. We use ratified BITs because merely signed BITs are not legally binding.Footnote 71 This variable is constructed using the International Investment Agreements database (UNCTAD website). In our sample, the variable ranges from 0 to 104; developing countries were, on average, subject to about eleven BITs.

We further explore the heterogeneity of BITs to determine the causal mechanism in our theoretical explanation. First, we emphasize the strength of investors’ legal protection. To explore the stringency of BITs, this variable codes only BITs for which the ICSID is the only option for dispute arbitration. This means that investors can directly use the ICSID for dispute settlements, without exhausting local remedies. The ICSID has leverage over developing countries due to its status as an international convention affiliated with the World Bank, because it provides very limited grounds for appeal and its awards have the same effect as national court judgements. The measure is based on Allee and PeinhardtFootnote 72 and our original coding of 420 additional BITs, with a range from 0 to 24 and an average of 4. Secondly, we want to capture BITs that regulate de facto investment, such that it is plausible that grievances in host countries come from favorable conditions granted to real investors. It is very likely that the BITs between developed countries and developing nations capture an investment relationship characterized by de facto flows of capital to the capital-poor developing nation. We use as a second measure only North–South BITs, as well as the BITs of major capital-exporting developing countries: Brazil, Russia, South Africa, China, Argentina, Panama, Mexico, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Hungary, Chile and India.Footnote 73 The variable ranges from 0 to 66, with an average of 7.Footnote 74

To test our second hypothesis, we use the polity2 score from the Polity IV dataset (−10 to 10, with larger values indicating higher levels of democracy). We include an interaction term between the polity2 score and the cumulative ratified BITs to test the conditional effect of investment treaties.

Control Variables

We use a baseline empirical specification with variables from Hafner-Burton.Footnote 75 Specifically, our controls include: (i) foreign investment measured as net FDI inflows as a percentage of GDP (UNCTAD);Footnote 76 (ii) the sum of a state’s total exports and imports as a share of gross domestic product (logged) (World Bank World Development Indicators – WDI); (iii) GDP per capita in constant US dollars (logged) (WDI); (iv) regime durability measured as the number of years since a state has undergone a structural regime transition, defined as a movement on the Polity scale of three points or more (Polity IV); (v) population per squared kilometer of land area (WDI); and, from Spilker and Bohmelt,Footnote 77 (vi) international human rights agreements capture whether countries have ratified the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the Convention Against Torture; (vii) soft PTAs measure whether a state belongs to any PTAs with soft human rights standards; (viii) hard PTAs is a dummy variable that takes a value of 1 if a state belongs to any PTAs with hard human rights standards. In addition to this baseline specification, we also include key covariates from the repression literature: two dummy variables code ongoing civil war and interstate war (Armed Conflict Dataset, Gleditsch et al. Reference Gleditsch, Strand, Eriksson, Sollenberg and Wallensteen2002). Also, following Nordas and DavenportFootnote 78 we include political dissent coded as the sum of antigovernment protest, riots and general strikes.Footnote 79 Additional variables are discussed in the robustness checks.

Model Specification

We use an OLS regression with panel-corrected standard errorsFootnote 80 and an AR(1) process,Footnote 81 as well as instrumental variable techniques. All models include country dummies to capture country-specific unobserved heterogeneity. We also include half-decade period dummy variables to account for time-specific shocks or time trends that may influence both human rights violations and BIT ratification. All independent variables are lagged by one year. The empirical model takes the following form:

$$CIRI_{{i,t}} \,{\equals} \,\alpha _{1} {\plus}\alpha _{2} \,BITs_{{i,t}} {\plus}\alpha _{3} \,Polity_{{i,t}} {\plus}\alpha _{4} \,BITs_{{i,t}} {\asterisk}Polity_{{i,t}} {\plus}\left[ {Controls} \right]{\plus}{\epsilon}_{{i,t}} {\plus}\eta _{i} {\plus}\mu _{t} $$

$$CIRI_{{i,t}} \,{\equals} \,\alpha _{1} {\plus}\alpha _{2} \,BITs_{{i,t}} {\plus}\alpha _{3} \,Polity_{{i,t}} {\plus}\alpha _{4} \,BITs_{{i,t}} {\asterisk}Polity_{{i,t}} {\plus}\left[ {Controls} \right]{\plus}{\epsilon}_{{i,t}} {\plus}\eta _{i} {\plus}\mu _{t} $$

We expect that α 2 is negative, indicating that BITs work to worsen countries’ human rights practices. α 4 should be positive, indicating that democracies mitigate the negative effect of BITs. Finally, based on the literature on repression, α 3 should be positive: democracies tend to have better human rights.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

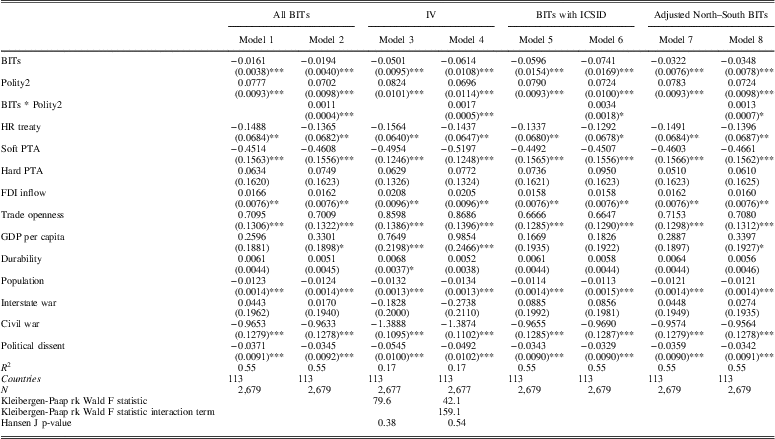

Table 2 presents our results. Models 1 and 2 use the cumulative number of all BITs as the key independent variable. Models 3 and 4 use an instrumental variable approach to estimate the effect of BITs on human rights practices. Models 5–8 use our alternative measures for relevant BITs, based on investors’ ability to litigate at the ICSID (BITs with ICSID; Models 5 and 6) and the likely existence of actual investment flows (Adjusted North–South BITs; Models 7 and 8). The empirical estimations support our two hypotheses. Models 1, 3, 5 and 7 include the un-interacted cumulative number of BITs and the polity2 score. Across all models, as expected, the coefficient on the cumulative number of investment treaties is negative and statistically significant. A greater number of BITs ratified by a country reduces the CIRI index, showing a worsening of human rights conditions. Models 2, 4, 6 and 8 include an interaction term between the cumulative number of ratified BITs and the polity2 score. The coefficient on the cumulative number of investment treaties continues to be negative and statistically significant, but the interaction term is positive and statistically significant. This supports our second hypothesis: democracy mitigates the negative effect of BITs on host governments’ respect for human rights.

Table 2 Effect of BITs on Human Rights in Developing Countries 1981–2009

Note: all models except 3 and 4 are OLS with panel-corrected standard error along with AR (1), intercepts, country and half-decade fixed effects. Models 3 and 4 are instrumental variable models (Stata command xtivreg2). The numbers in parentheses are standard errors. All independent variables are lagged one year. ***p≤0.01; **p≤0.05; *p≤0.1.

Very important, the relationship between BITs and human rights violations is open to the charge of endogeneity. It may be that states with a low level of respect for human rights are in greater need of the credibility afforded by ratifying BITs in the first place. Although there is no clear evidence in the literature that states with high levels of human rights violations ratify more BITs,Footnote 82 Models 3 and 4 show instrumental variable estimations to address the potential endogeneity problem. We use two instruments for our key independent variable, the cumulative number of ratified BITs. The first instrument measures the average of the total ratified BITs in neighboring states in a given year. We define neighboring countries using the Correlates of War coding for type 1 or 2 contiguity, which includes countries that share a land border or are separated by 12 miles of water or less.Footnote 83 This instrument aims to capture the competitive nature of BIT signing,Footnote 84 and the correlation of the instrument with our independent variable is 0.69. The second instrument uses the three-year lagged total of new BITs ratified by other countries. This instrument intends to capture the trend of BIT ratification and the opportunities to conclude BITs; its correlation with the key independent variable is 0.29. We use Stata command xtivreg2, and the results in Table 2 (Models 3 and 4) continue to support our hypotheses. The chosen instruments perform well: the Hansen test of over-identifying restrictions tests the overall validity of the instruments (including the choice of exogenous variables) and the failure to reject the null hypothesis gives support for the model. For Models 3 and 4, the Hansen J statistic Chi-sq(2) p-values are 0.38 and 0.54, respectively, so we cannot reject the null hypothesis. In instrumental variable models, while chosen instruments may be exogenous, they may be weak, biasing the estimated coefficients. For both Models 3 and 4, the weak identification Kleibergen-Paap rk Wald F statistic is above 42. This value easily passes the ‘rule of thumb’Footnote 85 test that the F statistic should be at least 10 for weak identification not to be considered a problem.Footnote 86 We use similar instrumental variables for the modified independent variables (BITs with ICSID and Adjusted North–South BITs), and the results shown in Table 2 (Models 5–8) are largely robust (online appendix).

A related, broader concern is that the effect of BITs reflects the preferences of actors involved in the bargaining over the BIT. We perform the following two tests to address such concerns: (i) Table 2 models a variable that captures the competition for capital among developing countries, which emerges as the key factor that drives countries to sign BITsFootnote 87 and (ii) we exclude treaties from our BITs count that were ratified less than 5 years previously, under the assumption that for older BITs, the coalition of interests in the ratification is much less likely to matter directly and the effect we identify belongs to the BIT. Our results are maintained (results available in the online appendix).

For interactive models, inferences should be made with meaningful marginal effects and standard errors to determine the conditions under which the variable of interest has a statistically significant effect.Footnote 88Figures 1(a, b, c, d) show the marginal impact of BITs on governments’ respect for human rights conditional on the level of democracy. Figures are based on Models 2, 4, 6 and 8, respectively. The marginal effect of cumulative BITs is negative and highly statistically significant in less democratic states, whereas in democracies the effect is much smaller and only marginally statistically significant. Very relevant for our argument, the size of the marginal effect from Figure 1(a) is smaller than that in Figures 1(c & d). This means that the effect of BITs with ICSID is about three times as large as the effect of all BITs, while the effect of adjusted North–South BITs is about 1.3 times as large.Footnote 89 This is consistent with our story that governments react to the legal protection of investors in international tribunals, and that the effect of BITs should be larger when it is more likely that they regulate de facto inflows of capital to developing countries.

Fig. 1 The marginal effect of BITs on human rights, conditional on regime type Note: Figure 1(a) is based on Model 2, Figure 1(b) is based on Model 4, Figure 1(c) is based on Model 6, Figure 1(d) is based on Model 8.

Further, we investigate the substantive impact of BITs. We use Models 2, 6 and 8 to predict human rights violations as we vary the cumulative number of BITs and the level of the Polity democracy score (Table 3). We vary the cumulative number of all BITs, BITs with an ICSID clause and the adjusted North–South BITs, as well as the polity 2 score one standard deviation above and below the mean. All other variables are held at their mean values. In non-democracies, varying the number of BITs by one standard deviation around the mean accounts for about 8 per cent of the variation in the CIRI dependent variable. For example, for BITs with the ICSID clause, moving from no BITs to seven BITs that include the restrictive clause on investment arbitrations reduces the predicted level of physical integrity rights from 3.94 to 3.28, or about 8 per cent of the 0–8 range of the dependent variable. For democracies, however, the same variation in the number of BITs has a smaller effect of about 4 per cent of the variation in the CIRI dependent variable.

Table 3 Predicted Human Rights Conditions: Vary BITs and Democracy

Note: Predictions are calculated using Stata command margins. The numbers in parentheses are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

The differences in predictions are statistically significant at the 95 per cent confidence level and, for non-democracies in particular, the size of this effect is important. For comparison, we compute the effect on the human right conditions of democracy, the key determinant of human rights in the repression literature. A move of one standard deviation above and below the mean in the polity2 score (keeping BITs at their mean values) accounts for about 13 per cent of the 0–8 range of the dependent variable (from 4.86 to 3.75).

We also explore the idea that treaties may have different effects depending on the partner country in the BIT, and break down the total number of BITs into two categories: BITs with advanced democracies and BITs with the rest of the world. Arguably, BITs with advanced democracies protect investors’ rights and could ‘export’ the human rights standards of advanced democracies to the investment host countries (or at a minimum not hurt human rights).Footnote 90 Despite the expectation that BITs with advanced democracies may have a different effect, our results hold: more treaties with advanced democracies or with the rest of the world worsens the human rights practices of developing countries (results available in the appendix).

Finally, regarding our control variables, we find that soft PTAs may increase repression levels, while hard PTAs have no impact; the ratification of human rights treaties is associated with worse practices across our models; the level of democracy, trade openness, GDP per capita, population density, civil war and political dissent are all significant predictors of human rights practices and take on expected signs. Importantly, we find that net FDI inflows are associated with better human rights practices. This effect, and the results supporting our hypotheses, is maintained when we use the ten-year lagged moving average of FDI inflows to mitigate the potential endogeneity between FDI and human rights practices.

By including both the cumulative number of BITs and FDI inflows in our models, we unpack the causal mechanisms through which FDI may affect human rights. Our models allow for a residual effect of FDI inflows, which appears to aid human rights.Footnote 91 This likely occurs via economic development and growth.Footnote 92 FDI has, however, been linked to human rights through opposing arguments. Work that traces itself to dependency theories argues that foreign investors co-opt local elites and extract local resourcesFootnote 93 or, alternatively, use exit threats as leverage for tax breaks, favorable labor policies and fewer welfare programs.Footnote 94 To sustain such investor-friendly policies, governments in developing countries arguably need to control the masses, including through curtailing political or human rights.Footnote 95 These opposing arguments are unlikely to be captured by the variables commonly used in the literature measuring the stock or flows of FDI. Our focus on BITs can thus directly capture the preferential treatmentFootnote 96 that many multinationals enjoy in developing countries, which is locked in by BITs. Empirically, the FDI measures included in our estimations should capture the residual effect of direct investment through channels such as economic development and improved living standards.

Causal Mechanisms

Our theory suggests that there are several causal paths that can link BITs to human rights violations. The effect likely goes through (i) increased grievances due to limitations on governments’ ability to tax and spend on subsidies or other measures to reduce poverty; (ii) increased grievances from a worsening of labor relations and conditions for workers; and (iii) social mobilization and states’ responses to actual and anticipated protest. To understand the empirical support for these causal paths, we first test the effect of BITs on labor practices,Footnote 97 fiscal revenue and fiscal expenditure (percent of GDP)Footnote 98 and observed political dissent (antigovernment protest, riots and general strikes). Because we argue for an effect of globalization that is mediated by domestic institutions, these models include the interaction term of BITs and the polity2 democracy score. Secondly, we aim to understand whether BITs influence human rights practices directly, as well as indirectly through the posited causal pathways. Thus we also test the effect of BITs on human rights violations when the intervening variables are included in our models.Footnote 99

All models and the detailed empirical specifications are included in the Appendix. The results suggest that BITs depress de facto labor practices with no mediating effect of democracy, and that BITs reduce both fiscal spending and revenue, but this negative effect is smaller in democracies. Our theoretical expectation is that governments respond not just to observed, but also to expected social mobilization. Here, however, we can only measure observed political dissent, and several of our empirical models show that the effect of BITs is mediated by the political regime: that is, BITs increase dissent, but not in democracies.

The empirical models also show that BITs influence human rights directly, as well as through the posited causal mechanisms. Political dissent is already included in our baseline models in Table 2. However, fiscal spending and revenue or labor rights both reduce our sample size and are not usually part of baseline models of human rights violations. We therefore include the variables operationalizing the causal mechanisms one at a time in our Table 2 models. We find that political dissent worsens human rights conditions, while more fiscal revenue and spending, as well as better de facto labor practices, are associated with improved human rights practices. In addition, in all the empirical models, BITs continue to have a negative effect on human rights, mediated by democracy.

Additional Robustness Checks

We verify the robustness of the empirical results to additional threats to inference. These include the timing of when BITs started to give investors access to international arbitration without the requirement to exhaust local remedies, the operationalization of the dependent variable, the presence of outliers and the effect of additional variables.

First, we restrict our sample to begin in 1990 because it was not until the late 1980s that BITs began to give investors access to investor–state arbitration without first having to exhaust local remedies. This strategy is similar to Poulsen and Aisbett,Footnote 100 who note that after 1990, the vast majority of BITs included a binding consent to investor–state arbitration. Our theory centers on multinational corporations’ leverage over host states, and therefore the magnitude of the lock-in effect of initial policies. Focusing on BITs with access to investor–state arbitration may be therefore a more appropriate way to capture the foreign investors’ leverage through BITs. We thus restrict our sample to BITs ratified after 1990 and show that our results remain robust (details available in the appendix).

Secondly, we use alternative measures of rights violations, including: (i) the average Political Terror Scale (PTS);Footnote 101 (ii) from the CIRI dataset, we only add the scores for the two most frequent incidences of rights infringements, torture and political imprisonment (range 0–4); and (iii) from the CIRI dataset, we use an additive index of freedom infringements, including freedom of foreign and domestic movement, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly and association, and freedom of religion (range 0–10).Footnote 102 The results, available in the online appendix, show that our findings remain substantively the same when we use these alternative measures of rights violations.

Finally, we exclude potential outliers and include additional control variables. Our results are substantively similar if we exclude: countries that are above the 99th percentile in terms of cumulative BITs ratified (China, Romania, the Czech Republic) or above the 95th percentile (China, Romania, the Czech Republic, Turkey, India, Egypt); one decade at a time from our estimation sample;Footnote 103 and major capital-exporting developing countries: Brazil, Russia, South Africa, China, Argentina, Panama, Mexico, Malaysia, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Hungary, Chile and India. We also test the robustness of our hypotheses by including additional control variables: (i) SimmonsFootnote 104 finds that states are more likely to sign restrictive BITs during economic downturns. Economic crisis may also induce governments to repress social unrest. We control for the three-year lagged average economic growth (WDI). (ii) Abouharb and CingranelliFootnote 105 find that International Monetary Fund (IMF) or World Bank adjustment programs tend to worsen human rights in loan-receiving countries. We control for the number of years that countries are under either IMF or Bank programs. (iii) The ‘shaming’ activities of human rights international NGOs may also improve states’ human rights practices. We control for this possibility by using a new dataset of shaming events of more than 400 human rights NGOs.Footnote 106 (iv) More corrupt governments could sign more BITs to substitute for poor respect for property rights. We control for corruption in our models (International Country Risk Guide) and our results hold, while we show that less corruption is associated with better human rights records. The Appendix shows that our results are largely robust to these additional estimations.

CONCLUSION

This article represents the first theoretical and empirical investigation into whether and how the global investment regime, particularly the ratification of BITs, affects human rights in developing countries. In these countries, we argue that BITs have the potential to worsen human rights practices because they lock in initial conditions that are attractive to investors, both retrospectively and into the future. Retrospectively, many developing countries are destinations of vertical investment and still compete for investment and trade on issues ranging from environmental regulations, taxes, labor standards and welfare spending, and BITs lock in these initial favorable conditions. In addition, BITs provisions can constrain states’ future policy choices for sustainable development, from the provision of basic infrastructure to investment in environmentally friendly technologies. Low de facto labor rights and constraints on development and social policies can be important sources of popular grievance. Repression and human rights violations are frequent state responses to actual or anticipated protest and dissent that can result from such grievances. We argue, however, that regime type moderates states’ reactions to threats and the negative human rights consequences of BITs. Democracies are less likely to offer investors more initially favorable conditions, as seen in tax incentive policies or de facto environmental standards. Also, relatively low levels of perceived threat of protest or dissent on regime stability and a high level of political accountability in democracies increase the cost of state repression and are more likely to balance out the favorable treatment that BITs give investors.

Using a sample of 113 developing countries from 1981 to 2009, we find support for our theoretical arguments. Countries with more ratified BITs have worse human rights practices. This effect holds, and is larger when we restrict our BITs count to only those treaties that have stringent arbitration clauses (ICSID arbitration) or are likely to govern actual investment flows (North–South BITs). In addition, we find that the effect of the cumulative number of ratified BITs is conditional on political regime type: BITs are more likely to result in human rights violations in non-democracies. Our analysis of the likely causal mechanisms shows that BITs constrain developing countries’ ability to tax and spend, worsen labor practices and contribute to political dissent, and BITs have both a direct effect on human rights and an indirect one through the posited causal mechanisms.

Our research draws attention to the unintended externalities of concluding BITs. Investment treaties were drafted to facilitate cross-border capital flows and promote development through foreign investment. Yet we provide robust evidence that ratifying BITs tends to worsen the human rights practices of developing countries, very likely because they tie the hands of governments. Our findings thus back calls from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development to restore states’ control over their regulatory space and to protect the rights of domestic constituencies.Footnote 107 They also support the recent move to incorporate human rights standards into the content of BITs, either by explicitly referencing human rightsFootnote 108 or by including related provisions with regards to labor standards or environmental protections.Footnote 109