The British parliamentary elections of 1997 and 2001 featured two very different incumbents. One was the Conservative Party, in power for eighteen years and headed by John Major, who had been a cabinet member for ten years and prime minister for the last seven. The other was the Labour Party, in power for four years and headed by relative newcomer Tony Blair. As British voters searched for clues in 1997 and 2001 about the quality of the incumbent, some probably considered the economic situation. Did the fact that these incumbents were so different affect what inferences they made about the economy? Did the fact that the incumbent party up for re-election in 1997 had been in power for almost two decades make voters consider the economy differently than in 2001, when the incumbent party had only been in power for four years?

Compelling answers to these questions cannot be found in the existing literature on economic voting, which has generally paid little attention to how differences in incumbent tenure moderate the economic vote.Footnote 1 While previous research has identified extensive variation in the extent to which voters use the economy to pass electoral judgment (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Lewis-Beck Reference Lewis-Beck1990; Paldam Reference Paldam, Norpoth and Lafay1991; Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin Reference Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin2007), this variation has primarily been explained with reference to the clarity of the political responsibility that the electoral context offers and to individual-level characteristics, such as partisanship or political knowledge (see, for example, Powell and Whitten Reference Powell and Whitten1993; Hellwig and Samuels Reference Hellwig and Samuels2007; Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Malhotra and Kuo Reference Malhotra and Kuo2008; Kayser and Wlezien Reference Kayser and Wlezien2011; Vries and Giger Reference Vries and Giger2014). To the extent that previous work has examined the potential moderating force of incumbent tenure, it has primarily, although not exclusively, looked at the short-term relationship between economic voting and tenure, studying how the economic vote develops during an incumbent's first term (see also Carey and Lebo Reference Carey and Lebo2006; Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier Reference Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier2008; Singer and Carlin Reference Singer and Carlin2013).

This article examines the long-term relationship between incumbent tenure and economic voting by developing a new theoretical model of how voters apply economic signals when judging incumbents with different levels of tenure, and by providing the most extensive empirical examination of this relationship to date.

Building on theories of Bayesian learning, the article argues that economic voting decreases with time in office. Bayesian learning is predicated on the idea that people rely less on new evidence when they have more prior evidence (Breen Reference Breen1999; Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green1999). Therefore if voters accumulate evidence about governments' competence over time, and if voters are Bayesian learners, they should rely less on current economic conditions when judging experienced governments. Returning to the British case, Bayesian learning would predict that voters relied more on the state of the economy when evaluating the relatively new Labour administration than when assessing the relatively old Conservative administration, because voters had more prior evidence about the Conservative government's quality – including their long-term economic performance and potential scandals – leaving the new evidence – the current state of the economy – less persuasive.

Empirically, the article examines the long-term relationship between economic voting and time in office using three different data sources. In particular, the article uses country-level data on the relationship between economic growth and support for executive parties in 409 elections across forty-one different countries; individual-level data on the relationship between retrospective perceptions of the economy and voting for the incumbent in sixty representative national surveys from Western European countries; and subnational data on local levels of unemployment and support for mayoral parties in Denmark. The results are consistent with the notion of Bayesian learning: the economy is more strongly related to incumbent support when voters have less experience with the incumbent. That is, incumbent tenure crowds out economic voting.

These results challenge at least two predominant models of economic voting. First, my findings challenge models that conceptualize economic voting as a game of ‘musical chairs’ in which voters blindly hold the incumbent responsible for recent economic performance (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017; MacKuen, Erikson and Stimson Reference MacKuen, Erikson and Stimson1992). Rather, this study suggests that voters primarily rely on recent economic conditions if they have little other information about the incumbent to go on (that is, when the incumbent has not been in office for long).Footnote 2

Second, my results challenge selection models of the economic vote which suggest that voters always rely more on economic conditions when these are more precise signals of incumbent competence (Alesina and Rosenthal Reference Alesina and Rosenthal1995; Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008) – including the main theoretical model used to explain differences in the economic vote: the clarity of responsibility model. Since economic policy does not have instantaneous effects, economic conditions presumably come to reflect an incumbent's competence more strongly over time, and voters should therefore become more responsive to economic conditions as incumbents' time in office increases.Footnote 3 I find the opposite. This is not to say that my results are fundamentally inconsistent with all kinds of selection models, but they do challenge models, such as the clarity of responsibility model, that narrowly focus on error in the competence signal. Instead my results suggest that the level of economic voting does not simply depend on whether current economic performance serves as a strong signal of the incumbent's actions, but also on the number of alternative signals voters have at their disposal.

In the next section, I detail the Bayesian learning explanation and expand on the theoretical tension between Bayesian learning and selection models of the economic vote. I also discuss the previous empirical work on tenure and economic voting in more detail. Then I go through the three studies of the long-term relationship between time in office and economic voting. I conclude by weighing some alternative explanations against the Bayesian learning explanation.

Bayesian Learning, Time in Office and The Economic Vote

Theories of Bayesian learning assert that the inferences people make are based on prior beliefs that are continually updated when new evidence is encountered (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green1999). In the context of economic voting, this means that when voters evaluate an incumbent, their assessment is based on their prior beliefs about the incumbent's quality, which they then update when observing the economic situation – the new evidence (Granato et al. Reference Granato2015). A key prediction from theories of Bayesian learning is that the extent to which people rely on new evidence when updating their beliefs depends on how strong their prior beliefs are. If prior beliefs are weak, people rely more on the new evidence than if prior beliefs are strong. Beliefs are stronger when those who carry them are more certain that they are true, and therefore any rational prior belief is a function of the amount of relevant information – that is, the amount of evidence – that has gone into shaping that belief.

What implications does this have for the relationship between economic voting and time in office? Relevant information naturally accumulates with time in office; that is, voters will always have more information about their incumbent's competence at t = x + 1 than at t = x, because all of the information accumulated by t = x is also available at t = x + 1. Accordingly, as an incumbent's time in office increases, voters' stock of relevant information increases, and this strengthens voters' beliefs about the incumbent. As a result, the beliefs become less malleable, attenuating the potential impact that new evidence, such as recent economic conditions, may have on these beliefs. Appendix Section S1 formalizes the argument.

This type of diminishing returns to new information might seem counterintuitive, but it also tracks well with how we extract information about the world in other settings. For example, it is a well-known fact from basic inferential statistics that increases in certainty about a population parameter become smaller with a larger sample size. In other words, we obtain a lot more certainty from an extra observation at n = 10 but only a little more certainty from an extra observation at n = 1,000. Similarly, recent economic conditions tell voters a lot about new incumbents, about whom they have made few other observations, but they only tell voters a little about experienced incumbents, for whom they have a large number of observations.

What type of relevant information do voters accumulate as an incumbent's time in office increases? Obviously, an incumbent's economic record grows larger with each passing year. Other relevant information may also crowd out the importance of economic information. This includes the absence or presence of scandals and corruption as well as the substantive policies enacted by the incumbent. It is important to note that the type of alternative information voters acquire is not important for whether Bayesian learning crowds out economic voting. The mere presence of some type of relevant information about the incumbent's quality, continually distributed during an incumbent's time in office, should decrease voters’ reliance on recent economic conditions, as their prior beliefs about the incumbent are strengthened.

Related to this, it is important to note that Bayesian learning will not necessarily reduce voters' overall reliance on economic conditions. This concept merely suggests that voters rely less on recent economic conditions as the incumbent's time in office increases, due to their mounting economic (and non-economic) record. Even so, Bayesian learning implies that economic voting decreases with time in office, because economic voting has – in the vast majority of the hundreds, if not thousands, of applications of this theory – been operationalized as the effect of economic conditions around election time on support for the incumbent.Footnote 4

Alternative Explanations

There are other reasons why economic voting might decrease with time in office. Voters might hone in on a first impression and be unwilling to update this impression in light of contradictory evidence (that is, a type of confirmation bias). Incumbents might grow more skilled at manipulating how voters perceive the economy as their time in office increases, dislodging the relationship between economic performance and incumbent support. Alternatively, there could be an ‘end-of-period problem’: voters and incumbents know that a governing politician will not be around for much longer, which may attenuate the relationship between economic policy outcomes and incumbent support (Besley and Case Reference Besley and Case1995). In the following, I privilege the Bayesian learning explanation and return to a broader discussion of these alternative explanations near the end of the article.

What about Clarity of Responsibility?

Previous work has explained how time in office moderates the economic vote in terms of the clarity of responsibility hypothesis. First developed by Powell and Whitten (Reference Powell and Whitten1993), this hypothesis suggests that economic voting depends on whether governments are, or seem to be, responsible for economic outcomes (see also Hellwig Reference Hellwig2001; Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008; Fisher and Hobolt Reference Fisher and Hobolt2010; Lobo and Lewis-Beck Reference Lobo and Lewis-Beck2012). Since more experienced incumbents will have had more time to enact policies that affect economic conditions, they might be perceived as more responsible for economic conditions (Nadeau, Niemi and Yoshinaka Reference Nadeau, Niemi and Yoshinaka2002). If this is the case, the clarity of responsibility hypothesis predicts that voters should become more responsive to economic conditions as time in office increases. Why do voters respond in this way? While the micro-foundations of the clarity of responsibility hypothesis are unclear (Parker-Stephen Reference Parker-Stephen2013), Duch and Stevenson (Reference Duch and Stevenson2008) use a selection model to show that it is rational for voters to respond more strongly to economic conditions when these conditions reflect incumbent competence more closely (also see Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2017).

Combining the Bayesian learning argument with this argument from the literature on clarity of responsibility, it becomes clear that countervailing forces affect the level of economic voting as time in office increases. On the one hand, as an incumbent's time in office increases their responsibility for economic outcomes grows as well, which gives voters an extra incentive to rely on recent economic conditions. On the other hand, voters' prior beliefs about the incumbent become stronger with time in office, which gives voters a disincentive to rely on recent economic conditions.

Which force, increased responsibility or strengthened priors, dominates? In Appendix Section S1 I present a formal model in which voters learn about the incumbent while the incumbent's responsibility for economic conditions increases. This model makes no uniform theoretical prediction about whether economic voting increases or decreases with time in office. Instead, it shows that voters' reactions will depend on their beliefs about the degree to which clarity of responsibility increases with time in office and on the overall relationship between incumbent competence and economic conditions. This theoretical ambiguity motivates the empirical investigation.

Existing Evidence

Only a small number of studies have examined how economic voting changes with time in office. For instance, Nadeau, Niemi and Yoshinaka (Reference Nadeau, Niemi and Yoshinaka2002) include time in office in a larger index of ‘dynamic clarity of responsibility’ and then explore whether this index correlates with the economic vote in eight European countries. They find that their index has a positive relationship with economic voting, but they do not examine time in office separately from the other factors. Studies by Carey and Lebo (Reference Carey and Lebo2006) and Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier (Reference Lebo and Box-Steffensmeier2008) examine how the nature of economic voting changes across the election cycle. Focusing on the US and UK, respectively, they tend to find more prospective economic voting at the beginning of an election cycle and more retrospective economic voting at the end of a cycle.

In the most thorough examination of the relationship between time in office and the economic vote, Singer and Carlin (Reference Singer and Carlin2013) link time in office with different types of economic voting in a wide cross-section of Latin American countries. They find that ‘voters’ reliance on prospective expectations indeed diminishes over the election cycle as the honeymoon ends and they retrospectively evaluate the incumbent's mounting record’ (Singer and Carlin Reference Singer and Carlin2013, 731). Although their study is well executed and convincing, it is limited by two factors. First, it measures economic voting by looking at economic perceptions, rather than objective economic conditions. Secondly, and more importantly, they focus on the short-term relationship between time in office and the economic vote. This is partly because they analyze a relatively politically volatile region, and partly because they primarily study presidential systems. As a result, most of the incumbents they examine have only been in office a short time: roughly 90 per cent have held office for less than five years, and the median time in office is 2.5 years. The authors are aware of this limitation, and thus their theoretical predictions and key findings tend to be concerned with the first few years of the incumbent's time in office (Singer and Carlin Reference Singer and Carlin2013, fig. 1, 738).

Taken together, these studies have made important headway in exploring the relationship between time in office and the economic vote, but at least two important empirical questions remain unanswered. First, what is the long-term relationship between tenure and the economic vote? In many countries, the same incumbent party has been in power for many years – sometimes more than a decade. While prior studies assess how economic voting evolves during the first election cycle, we know little about what happens after that. Is there, for instance, a difference between an incumbent who has been in office for four years and one who has been in office for ten? Secondly, is there a relationship between the extent to which objective economic conditions affect support for the incumbent and time in office? Previous studies have exclusively focused on how the effect of prospective and retrospective economic perceptions change as time in office increases; however, we do not know whether the effect of objective economic conditions changes with time in office.

Country-Level Evidence

I begin my investigation of the relationship between tenure and the economic vote by examining a country-level dataset of national elections. Numerous other studies have used this type of data to analyze variation in the economic vote (see Powell and Whitten Reference Powell and Whitten1993; Whitten and Palmer Reference Whitten and Palmer1999; Hellwig and Samuels Reference Hellwig and Samuels2007; Kayser and Peress Reference Kayser and Peress2012). The chief advantage of this approach is that it sidesteps problems of endogeneity related to using voters' perception of the economy by applying objective economic indicators instead (Kramer Reference Kramer1983, Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin Reference Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin2007, 26). The chief disadvantage is that the economic indicators that are used are country-level aggregates. These aggregates are noisy estimates of the economy as experienced by the individual voter (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008, 26), and they are restricted to n = 1 per election, limiting the statistical power of the analysis. To overcome these problems, I use a relatively large sample of elections and, later in the article, I replicate my findings using an individual-level approach.

Data and Model

I use a dataset of 409 elections held in forty-one countries (see Appendix Section S2 for a list of the countries and elections). To obtain such a wide cross section of elections, I use and amend datasets developed by Kayser and Peress (Reference Kayser and Peress2012) and Hellwig and Samuels (Reference Hellwig and Samuels2007). The key dependent variable is the percentage-point change in electoral support for the executive party in legislative and executive elections (Δy).Footnote 5 The executive party is the party that had primary control of the executive branch at the time of the election (that is, the party of the prime minister or president). Using the executive party rather than the parties in government is common in the literature (see, for instance, Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008). Further, several studies have shown that the executive party is much more prone to electoral judgement than other governing parties (Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin Reference Van der Brug, Van der Eijk and Franklin2007; Fisher and Hobolt Reference Fisher and Hobolt2010; Debus, Stegmaier and Tosun Reference Debus, Stegmaier and Tosun2014; although see Hjermitslev Reference Hjermitslev2018).

The key independent variables are economic growth (gr) and tenure (ten). Economic growth is a proxy for a country's economic conditions; it is measured as election year GDP per capita growth (pct.). This indicator is used because it is available for a large cross section of elections and because it has been widely used in previous studies. For elections occurring in the first six months of the year, I use economic growth in the year prior to the election year; for elections occurring in the last six months of the year I use economic growth in the election year. Data on economic growth was taken from the World Bank's database (World Bank, 2019). Time in office is measured as the number of years since the current executive party came into power. I focus on the tenure of parties, since the main dependent variable is support for the executive party. Data on tenure is taken from the database of political institutions (Beck et al. Reference Beck2001), and has been extended by the author to create better coverage for the electoral variables. The average level of tenure for the incumbent parties is six years, and the median is five years. See Appendix Section S3 for descriptive statistics on all of the variables.

Turning to modelling, I set changes in electoral support as a linear function of tenure, economic growth and an interaction between the two. I also include support for the incumbent party when it first came to office, and a dummy variable that indicates whether the election is executive or legislative (exec) to take into account the fact that economic voting works differently in executive and legislative elections (Hellwig and Samuels Reference Hellwig and Samuels2008; Samuels Reference Samuels2004). The baseline model I estimate can be described as follows:

The coefficient of interest is γ, which signifies the change in the effect of economic growth as tenure increases. A Negative (positive) γ coefficient indicates that economic voting decreases (increases) with time in office.

Results

Table 1 presents key estimates from the model described in Equation 1 in Column 1 using a maximum-likelihood estimator to obtain country-clustered standard errors. The growth and tenure coefficients should be interpreted as the effect of the variable when the other variable is held at zero. The baseline effect of economic growth is thus estimated to be 0.68, and can be understood as the (theoretical) effect of economic growth on the change in electoral support if an incumbent runs for re-election without any tenure.

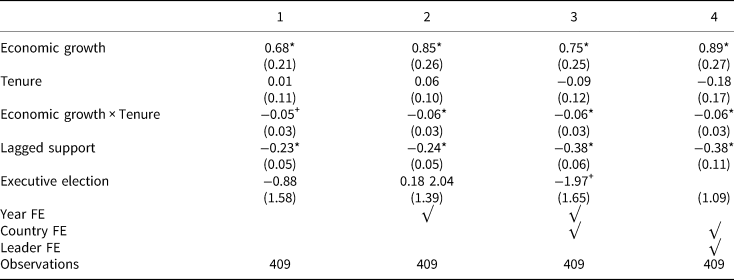

Table 1. Linear regression of changes in executive party vote share

Note: standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. + p < 0.10, * p < 0.05

The variable of interest is the interaction between economic growth and tenure. The interaction is statistically significant (p < 0.1) and negative, suggesting that the positive effect of economic growth at the beginning of an executive party's tenure diminishes over time. Specifically, the estimate suggests that each year, the effect of economic growth on electoral support drops by 0.05 from the starting point of 0.68. Accordingly, this model suggests that after thirteen years in office, the effect of economic growth is essentially zero.

To investigate this finding's sensitivity to different model specifications, I extend the baseline model in three ways. Column 2 shows estimates from a model that includes year fixed effects. These take global trends in growth, tenure and incumbent support into account. This leaves the interaction practically unchanged. Column 3 shows estimates from a model that includes country fixed effects. These control for potentially confounding differences in tenure and economic growth across different countries. The interaction remains negative and statistically significant (p < 0.05).

Column 4 of Table 1 includes leader fixed effects – that is, a dummy for each of the 159 incumbents in the dataset.Footnote 6 Including leader fixed effects means that any factors that are constant within the same incumbent are omitted when estimating the interaction. As such, the model estimates the interaction by comparing the degree to which the same executive party is punished or rewarded for the economic situation across elections (rather than by comparing different executive parties with different tenure lengths). The leader fixed effects make the year fixed effects less relevant, as I am now comparing levels of economic voting across a relatively short span of time (that is, from the beginning to the end of an incumbent's tenure). Further, if year fixed effects are included along with leader fixed effects, the degrees of freedom drop dramatically; they are therefore omitted from the model with leader fixed effects. The interaction estimate is virtually unchanged by the inclusion of leader fixed effects and is statistically significant (p < 0.05). Figure 1 plots the interaction using this specification.

Figure 1. Marginal effects of economic growth on change in electoral support for the executive party across levels of tenure

Note: I only plot tenure from the 5th to the 95th percentiles. Derived from the model presented in Column 4 of Table 1. The bar plot shows the density of the variable years in office. Includes 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Robustness Checks and Auxiliary Analyses

The Appendix describes four additional robustness checks. First, I evaluate whether the results are sensitive to using the average growth rate across the previous two years rather than simply the election year. This does not substantially affect the results (see Appendix Section S4). Secondly, I investigate whether adding additional controls for parliamentary and government composition affects the results. This means omitting a large number of elections for which this information is not available and increasing the standard errors that are attached to the estimates. However, the interaction estimates are not affected by adding the controls (see Appendix Section S5).

Thirdly, I look at whether a single country is driving the results. I find that the interaction estimate in Columns 1 and 2 is not sensitive to excluding a single country. For the models in Columns 3 and 4, excluding Luxembourg draws the interaction closer to zero. However, the interaction remains negative even when I exclude this country (see Appendix Section S6). Fourthly, in Appendix Section S7 I examine the interaction between economic growth and tenure in light of the different diagnostics suggested by Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2016). Overall, I find monotonicity in the average marginal effects and approximate linearity. However, I also find that the interaction variable is kurtotic, which calls into question the reliability of the interaction estimate.

In conclusion, my analysis of the country-level data suggests that economic growth becomes a less important determinant of an executive party's vote share as the party's time in office increases. Even so, the estimated interaction effect was not consistently strongly statistically significant. In part, this can be explained in terms of the low statistical power of country-level analyses – as mentioned above, the chief disadvantage of using country-level data is that it is quite noisy. To address this potential problem, I conduct a conceptual replication using individual-level data in the next section.

Before moving on to the replication, however, a few alternative explanations needs to be discussed. First, the negative correlation between tenure and economic voting might be due to strategic election timing (Kayser Reference Kayser2005; Samuels and Hellwig Reference Samuels and Hellwig2010). That is, the findings reported above might simply reflect the fact that certain types of leaders call early elections, and are therefore more likely to have shorter tenures when they run for re-election. In the Appendix, I examine this alternative explanation by trying to control away election timing in two different ways: (1) by including a control indicating how often incumbents call elections and (2) by restricting the sample of elections to countries with fixed terms, where strategic election timing is not possible. Using both of these methods, I show that in the most demanding specification, which includes leader fixed effects, the interaction remains negative, it is of the same approximate size, and it is statistically significant (see Appendix Section S8).

A second possible alternative explanation for the negative interaction I find is that voters initially hold only the executive party electorally accountable, but as time goes by begin to hold government coalition partners accountable as well. To test whether this is the case, I estimate the models from Table 1 separately for coalition governments and single-party governments in Appendix Section S9. I identify no systematic differences across the two groups, which suggests that the negative interaction term cannot be explained by voters holding coalition partners more accountable as their time in office increases.

Finally, I look at whether these results can be ascribed to the fact that I study incumbent parties (for example, the UK Labour Party) rather than executive officers (for example, Tony Blair). To do this, I add a control to the model that indicates whether the incumbent party and the executive officer have different lengths of tenure and an interaction between this variable and economic growth. The results, reported in Appendix Section S10, show that this does not shift the interaction estimates substantially, although the level of statistical significance drops from 5 per cent to 10 per cent.

Individual-Level Evidence

Having established a relationship between economic voting and the tenure of the executive party at the country level, I now explore the same relationship at the individual level. In essence, I try to replicate my results by investigating whether voters rely less on their perceptions of the national economy when deciding whether to vote for a more experienced incumbent. To do this, I closely follow a recent study by Nadeau, Lewis-Beck and Bélanger (Reference Nadeau, Lewis-Beck and Bélanger2013). They investigate the relationship between national economic perceptions and voting behavior in ten Western European countries over the past twenty years. This gives us a well-established empirical model of the economic vote, allowing us to simply extend this model to include an interaction between tenure and economic perceptions.

Data and Model

I use the European Election Studies survey of all EU countries, which has been conducted every fifth year since 1979. Since they are fielded in the year of European Parliamentary elections, their timing is somewhat independent of national election cycles. I use the six Europe-wide studies that have been conducted since 1989 (in 1989, 1994, 1999, 2004, 2009 and 2014), because these are the only surveys that include questions about national economic perceptions as well as vote intention in national elections. Moreover, I focus on the ten countries that participated in all six survey rounds: Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Ireland, Italy, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom (see Appendix Section S2 for details about the sample used). This gives us 60 cross-sectional national surveys, which can be pooled to test whether the effect of economic perceptions on voter intentions depends on the tenure of the executive party.

Turning to indicators, the key dependent variable is whether respondents report that they would vote for the executive party if a national legislative election were held tomorrow (Re-elect). The key independent variables are national economic perceptions and tenure. National economic perceptions (NEP) are measured using a question that asks respondents whether the economic situation in their country had become better or worse in the past twelve months. Responses were recorded on a five-point scale (except for the 1999 election study, which used a four-point scale). Tenure (Ten) is measured as the number of years the executive party had been in power at the time of the survey. Once again, this variable is taken from the Database of Political Institutions (Beck et al. Reference Beck2001) and extended to provide complete coverage for the sixty surveys. The average time in office is five years and the median is four years.

I use the same control variables that Nadeau, Lewis-Beck and Bélanger (Reference Nadeau, Lewis-Beck and Bélanger2013) apply in their economic voting model: respondents' ideology, self-perceived class, church attendance and a dummy indicating whether the respondent voted for the executive party in the last election.Footnote 7 All variables are rescaled to range from zero to one and recoded so that higher values indicate an increased propensity to vote for the executive party.Footnote 8 See Appendix Section S3 for the exact question wording and descriptive statistics.

I model the probability that voters will report an intention to vote for the executive party as a logistic function of national economic perceptions, tenure, an interaction between the two and the individual-level controls. The model I estimate can be described as follows:

where i indicates country, t year and j the respondent. X is a row vector of the control variables ideology, class, religion and past vote, and β is a column vector of coefficients attached to these controls. The coefficient of interest is once again γ, which signifies the change in the effect of national economic perceptions as tenure increases. Based on the results of the country-level data, which showed that the effect of current economic conditions decreases with time in office, I expect γ to be negative.

Results

In the first column of Table 2, I estimate the parameters of the model presented in Equation 2 using a multi-level logistic regression. I cluster the standard errors at the country level and estimate random effects at the survey level.Footnote 9

Table 2. Multi-level logit model of voting for the executive party

Note: standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. Tenure omitted in Model 3 due to collinearity with Survey FE. + p < 0.10, * p < 0.05

Ideology, class, religiosity and lagged executive party vote all have the expected signs and, apart from religiosity, are statistically significant. The baseline economy and tenure effects should (once again) be interpreted as the effect of the variable when the other variable is held at zero. The baseline effect of national economic perceptions is estimated to be 1.85, and can thus be understood as the (theoretical) effect of thinking the economy is doing a lot better rather than a lot worse on the logit probability of voting for an executive party without any tenure.

The key estimate of interest is the one attached to the interaction between national economic perceptions and tenure, which signifies how the effect of national economic perceptions changes as tenure increases. The interaction coefficient is statistically significant and negative, suggesting that the effect of national economic perceptions on support for the executive party diminishes as the executive party's time in office increases – an interaction effect that is qualitatively similar to the one found in the country-level analysis.

I also investigate whether these individual-level findings are sensitive to different model specifications. Column 2 includes leader fixed effects (see the country-level data). Estimating this more demanding model does not substantially change the results; the interaction remains negative and statistically significant. Column 3 introduces survey fixed effects and a dummy for each of the sixty surveys; the interaction remains negative and statistically significant.

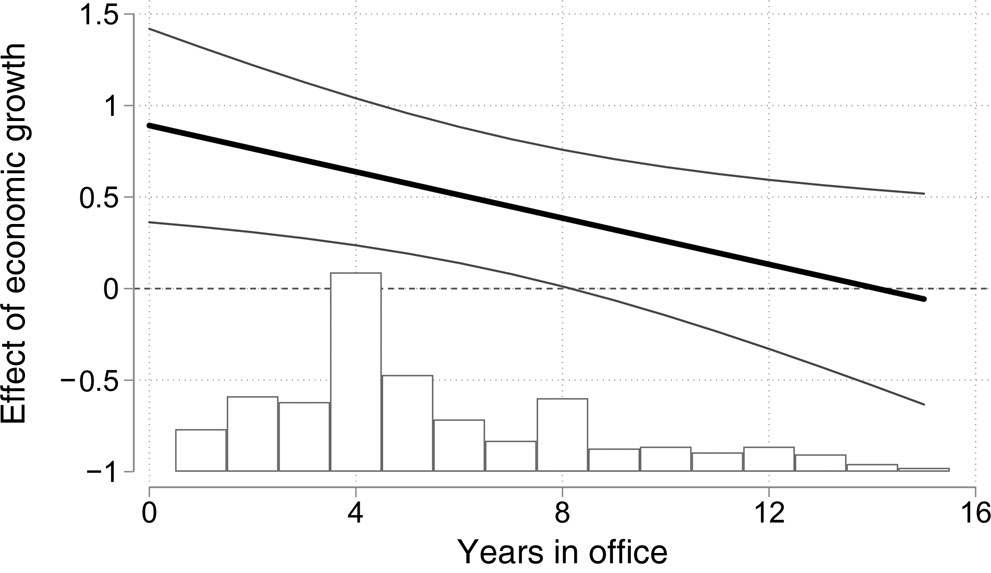

Finally, I derive the average marginal effects of national economic perceptions across different levels of tenure based on the model with survey fixed effects. Figure 2 shows how the average marginal effects of national economic perceptions decrease as tenure increases. For an executive party with one year of tenure, the effect of perceiving the economy as doing much better rather than much worse increases the probability of voting for the executive party by about 13.2 percentage points. For an executive party with fifteen years of tenure this leads to a 7.6-percentage-point increase. A comparison of the average marginal effect at one year of tenure and fifteen years of tenure reveals that this decline is statistically significant (p < 0.01).

Figure 2. Average marginal effects of national economic perceptions on the probability of voting for the executive party across levels of tenure

Note: I only plot tenure from the 5th to the 95th percentiles. Derived from the model presented in Column 3 of Table 2. The bar plot shows the density of the years in office variable. Includes 95 per cent confidence intervals.

Robustness Checks and Auxiliary Analyses

In the online appendix, I conduct a number of additional robustness tests of the interaction. I show that the results are robust to a two-step estimation procedure (see Appendix Section S11), and that they are not sensitive to outliers (see Appendix Section S6). I also examine the robustness of the interaction in light of Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2016) (see Appendix Section S7).

I use a standard retrospective question above. Here voters are asked about their country's economic performance in the past year. However, some studies of American politics have suggested that when an executive party has been in office for a while, retrospective concerns give way to prospective concerns (Nadeau and Lewis-Beck Reference Nadeau and Lewis-Beck2001). That is, voters' beliefs about how the economy is going to develop become more important than their beliefs about how the economy has developed.Footnote 10 Based on this, one might suspect that the reason we see a drop in the effect of retrospective economic perceptions is that the type of perceptions that matter at the beginning of the term are different from those that matter at the end of term. To test whether this is the case, I examine the relationship between vote intention, prospective national economic perceptions and time in office in Appendix Section S12. I find a similar pattern for the prospective economic perceptions as I do for the retrospective perceptions studied above. As such, there are no signs that some other type of economic perceptions becomes more important as the effect of retrospective national perceptions subsides.

While the individual-level results seem to line up nicely with the findings from the country-level study, there is one important inconsistency. While both studies show that the economic vote declines with time in office, the decline seems to be less dramatic in the individual-level data. In the country-level data, the estimated effect of the economy is essentially zero after fifteen years (see Figure 1). In the individual-level data, there is still a substantial amount of economic voting left after fifteen years (see Figure 2). One explanation for this inconsistency is that the individual-level data overestimates the amount of economic voting across all levels of tenure.

Many studies suggest that we generally overestimate economic voting when using voters' perceptions of the economy rather than objective economic conditions (Evans and Andersen Reference Evans and Andersen2006; Evans and Pickup Reference Evans and Pickup2010; although see Lewis-Beck, Nadeau and Elias Reference Lewis-Beck, Nadeau and Elias2008). These studies argue that partisan voters adjust their perceptions of the economy based on their underlying party preferences, leading to inflated estimates of the economic vote (Bartels Reference Bartels2002; Tilley and Hobolt Reference Tilley and Hobolt2011). In other words, economic perceptions might be ‘partisanship, thinly disguised’ (Kramer, Reference Kramer1983; as quoted in Lebo and Cassino Reference Lebo and Cassino2007). This might explain the discrepancy between the individual- and country-level results.

In Appendix Section S13, I try to correct for this type of partisan-induced endogeneity in two ways. First, I examine what happens when I exclude potential pro-government partisans. Secondly, I use objective economic conditions as instruments of national economic perceptions. In both cases, I find that correcting for endogeneity tends to align the individual-level results with the country-level data. This suggests that the immediate divergence between the country- and individual-level results can be explained by the methods used to measure the economic vote in the two different analyses – not by any real difference in how voters behave.

Taken together, the individual-level results thus reaffirm the country-level findings. As the incumbent party's time in office increases, the economy becomes less predictive of their electoral fortune.

Subnational Evidence

Why is there a negative long-term relationship between economic voting and time in office for a large cross-section of countries and elections? Above I argued that the reason can be found in theories of Bayesian learning. Since voters' stock of relevant information about the incumbent naturally increases with time in office, voters' beliefs about the incumbent become more certain, and voters therefore become less responsive to new information. As a result, the economic situation comes to play less of a role in shaping voters' beliefs about the incumbent. In this third and final study, I investigate the relationship between tenure and economic voting in a more controlled setting, which allows me to focus on this theoretical mechanism.

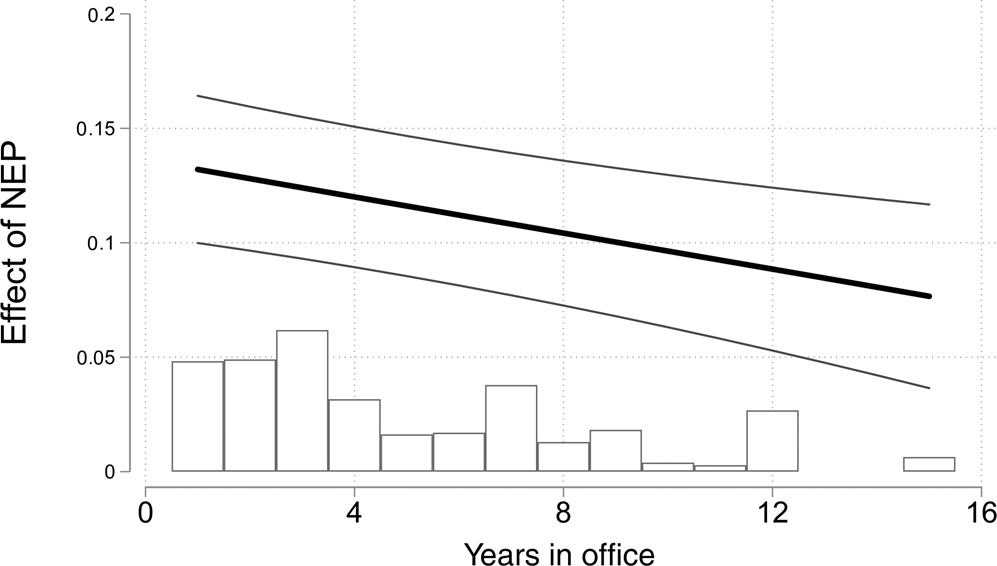

This study assesses a set of municipal elections in Denmark that took place after a 2005 jurisdictional reform in which a large number of municipalities merged.Footnote 11 This reform allows us to isolate variation in voters' experience with the incumbent – the key factor I believe is driving down economic voting as time in office increases – while holding attributes of the political system, the election and the incumbent constant.

To see how we can use the reform in this way, consider the following stylized example. Municipality 1 and Municipality 2 merge as a result of the jurisdictional reform. Before the merger, Party A was the mayoral party in Municipality 1 and Party B was the mayoral party in Municipality 2. In 2005 these municipalities merge and have to elect a mayor from one party. Let us say that they elect Party A. In the following election (in 2009), the voters in the newly merged municipality have to decide whether to re-elect the incumbent Party A. The voters who lived in Municipality 1 before the reform have accumulated information about Party A's ability to govern effectively both before and after the reform. The voters who lived in Municipality 2 before the reform have only accumulated information about Party A after the reform. Figure 3 visualizes this example.

Figure 3. A stylized example of the consequences of the jurisdictional reform process

Note: the shading denotes the amount of experience the electorate has with the incumbent mayoral party.

If more experience with an incumbent drives down economic voting, then I expect economic voting to be less prevalent among voters who lived in Municipality 1 and more prevalent among those who lived in Municipality 2. Conversely, if experience with the incumbent party does not matter, I should expect no difference in economic voting behavior. Importantly, if I do find a difference, I know that it cannot be attributable to the incumbent's type, which is the same for both groups of voters, or the type of political system (which is also the same). In this way I leverage the jurisdictional reform process to conduct a cleaner test of whether experience with an incumbent – the key factor Bayesian learning suggests is driving down economic voting – actually drives down economic voting.

Data and Model

To study the consequences of the jurisdictional reform, I examine election returns from the 2009 Danish municipal elections. In particular, I construct a dataset based on returns from 1,465 different precincts (that is, polling places). Each precinct lies within one of 239 original municipalities (pre-reform) and sixty-six merged municipalities (post-reform). I collected this data from the Danish Election database.Footnote 12 I do not use data from precincts located in municipalities that did not merge as a result of the reform, because these do not exhibit the type of within-municipality variation I am interested in (see Figure 3).

In Danish municipalities, mayors are not directly elected; they are appointed by a majority of the members of the city council. Often, this means that a coalition of two or three ideologically similar parties decide to appoint a mayor from the largest party. Accordingly, the key dependent variable is change in electoral support between 2009 and 2005 for the incumbent mayoral party in city council elections Δy.

The key independent variables are changes in the municipal unemployment rate from 2007 to 2009 Δunem and a dummy indicating whether the voters in the precinct had a different incumbent before and after the reform (Newinc).Footnote 13 Note that because all of the municipalities studied here merged with other municipalities in 2005, the variable Newinc varies within the merged municipalities. Appendix Section S3 includes descriptive statistics on all variables.

Turning to modelling, I set precinct-level changes in support for the mayoral party as a linear function of whether voters had a different incumbent than before the reform (Newinc), changes in municipal unemployment levels (Unem), and an interaction between the two. I also include post-reform municipality fixed effects θ, as well as a control for the level of support for the mayor in the last election (lagy). I include municipality fixed effects to make sure that I am only comparing electorates which have the same incumbent (that is, precincts within the same post-reform, merged, municipality). This leaves us with the following baseline model:

where i indicates precinct and j indicates the post-reform municipality. The key estimate of interest is once again γ, which denotes the difference in the effect of changes in the unemployment rate between voters who have a new incumbent and voters who have the same incumbent as before the reform. I expect γ to be negative, implying that increases in the unemployment rate have a larger negative effect on support for the mayoral party in precincts where the incumbent mayoral party is new.Footnote 14

Results

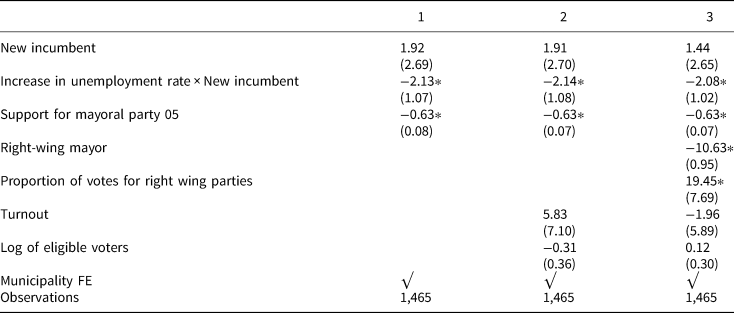

In the first column of Table 3, I estimate the model presented in Equation 3, using a maximum-likelihood estimator to obtain municipality-clustered standard errors. Note that the baseline effect of increases in the municipal unemployment rate is not estimated because the baseline is perfectly collinear with the post-reform municipality fixed effects.

Table 3. Linear regression of change in support for the incumbent mayoral party

Note: standard errors clustered by country in parentheses. + p < 0.10, * p < 0.05

The key estimate of interest is the one attached to the interaction between increases in the unemployment rate and whether the incumbent is new to the electorate. Consistent with my expectations, the interaction estimate is negative and statistically significant. This suggests that increases in the unemployment rate have a larger effect on support for the incumbent mayoral party in precincts where voters have had less experience with the incumbent mayor.

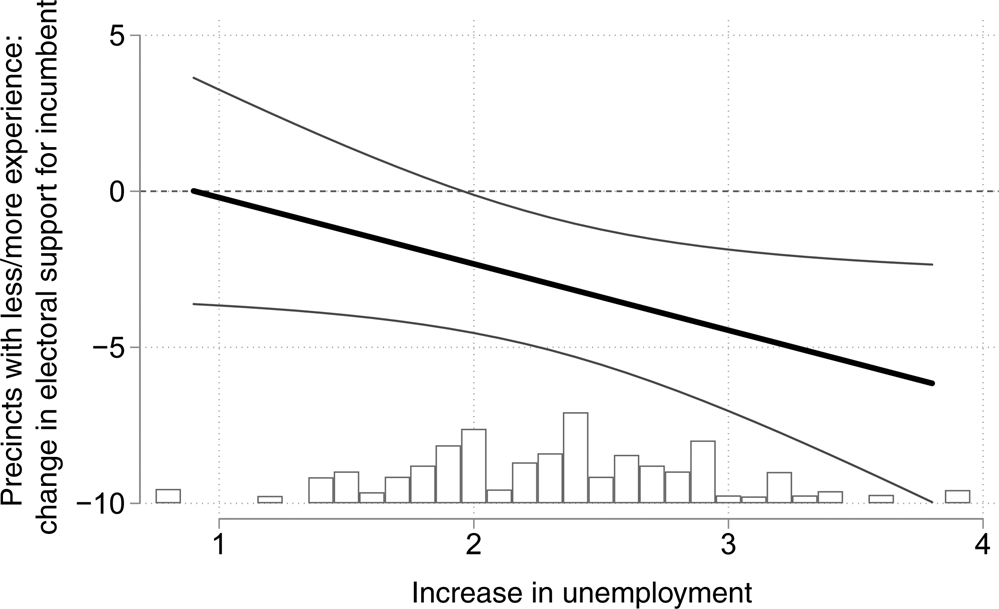

Figure 4 illustrates this interaction effect by plotting the difference in support for the mayoral party between precincts where the voters have a lot of experience with the mayor (both pre- and post-reform) and precincts where the voters have little experience with the mayor (only post-reform) across increases in the unemployment rate.Footnote 15 The figure shows that in municipalities where the unemployment rate did not increase, the mayoral party was just as popular in precincts where voters had little experience with the incumbent as in those where the voters had a lot of experience with the incumbent. However, in municipalities that experienced a substantial increase in the unemployment rate, the mayoral party was far less popular among those who did not know it well. Put differently, those without a lot of prior experience with the mayoral party were more affected by recent increases in local levels of unemployment than those with a lot of prior experience.

Figure 4. Difference in electoral support for the mayoral party between precincts in which voters had the same incumbent before and after the reform and precincts without increases in the municipal unemployment rate

Note: derived from the model presented in Column 1 of Table 3. The bar plot shows the density of increases in the unemployment rate. Includes 95 per cent confidence intervals.

As I did for the country- and individual-level results, I examine whether these subnational results are sensitive to alternative specifications. In particular, I am interested in determining whether characteristics of the precincts might explain the differences in economic voting between those who have experience with the incumbent mayor and those who do not. To control for the demographic characteristics of the precincts, I add controls for turnout and the size of the electorate in the second column of Table 3. To control for the ideological make-up of the precincts, I add controls for whether the mayoral party is right wing and for the proportion of voters that voted for a right-wing party in the third column. Including these controls does not affect the interaction estimate. It remains statistically significant, negative and of the same approximate size.

In the online appendix I also investigate the robustness of the results. In particular, I examine whether the interaction estimate is sensitive to outliers in Section S6, and whether the interaction is robust to the checks suggested by Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu (Reference Hainmueller, Mummolo and Xu2016) in Section S7. In Section S14 I find that the unemployment rate in 2005, turnout (as a proxy for political engagement) and support for right-wing voters are balanced across the key ‘treatment’ variable (that is, whether voters had the same incumbent before and after the reform). I find only one small imbalance: precincts assigned to a new incumbent seem to have fewer eligible voters. I do not believe this imbalance poses a serious threat to causal inference.

In summary, voters who had more time to get to know an incumbent (for example, those who had the same mayoral party both before and after the reform) were less likely to shift their support to or away from the incumbent based on how the economy was doing around election time.

Some Alternative Explanations

The three studies described above all suggest that as time in office increases, the effect of recent economic conditions on support for the incumbent decreases. I have argued thus far that the principal reason for this decline is Bayesian learning. As time in office increases, so does the stock of relevant information voters have used to assess the incumbent's quality, leaving voters' assessments less influenced by good and bad economic news. However, one could also think of other reasons why incumbent tenure crowds out economic voting. In this section, I briefly discuss the merits of some different alternative explanations derived from the existing literature on economic voting.

Voters’ perceptions of the economy are filtered through political elites such as the media (Soroka Reference Soroka2006) and parties (Bisgaard and Slothuus Reference Bisgaard and Slothuus2018). Following this general idea, one might imagine that as an incumbent becomes more experienced and better known, they can more easily shape how voters perceive the economy. If experienced incumbents are able to dislodge voters' perceptions of the economy from the actual economic situation in this way, the result would be a negative relationship between time in office and the economic vote. However, this persuasion explanation does not fit well with parts of the evidence presented above. In particular, this explanation offers no account of why voters, who are not persuaded by experienced incumbents to perceive the economy as doing well, should neglect to punish the incumbent. Yet I find that differences in incumbent support between those who think the economy is doing well and those who think it is doing poorly decrease with time in office (see Figure 2).

Numerous studies have shown that once voters have developed a set of beliefs about a political entity, they are likely to ignore evidence that casts doubt on this belief; this is conventionally referred to as confirmation bias or motivated reasoning (for example, Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013; Evans and Andersen Reference Evans and Andersen2006). If one assumes that when an incumbent is first elected voters have very few preconceptions about their abilities, then voters' beliefs are likely to be especially malleable in this period. For instance, these initial beliefs might be shaped by the state of the economy. Once an early impression is formed, however, confirmation bias might lead voters to ignore subsequent economic performance. This alternative explanation is more difficult to dismiss, partly due to its similarity to the learning explanation in terms of observable implications (Gerber and Green Reference Gerber and Green1999). To disentangle the two, a more controlled setting is required than the one offered by the observational studies reported in this article.Footnote 16 However, one piece of evidence from the individual-level study challenges the idea that confirmation bias is driving down the economic vote. In particular, I found that the degree of reduction in economic voting was about the same for pro-government partisans and non-partisans (see Appendix Section S13). If the reduction in economic voting was the result of confirmation bias, I would, all else equal, expect a greater reduction in economic voting among those who felt an allegiance to the incumbent party.

Previous studies also suggest that there is an ‘end-of-period’ problem in economic voting: incumbents who know their time is up (for example, due to term limits or unfavorable polls) give up on shepherding the economy (for example, Besley and Case Reference Besley and Case1995). If this is true, I should expect economic voting to be relatively stable and then dip at more extreme values of time in office. To test this alternative explanation, I split my moderating variables from the individual- and country-level studies into three equally sized bins (that is, a lower, middle and top tercile) and interact these bins with the economic variables. I find that the decline in effect size is fairly linear (see Appendix Section S7 for detailed results). Economic voting does not only decrease at the highest levels of tenure. Instead, the importance of economic conditions gradually declines.

Overall, I think each of these alternative explanations falls short of Bayesian learning in terms of explaining the results presented in this article. Yet the primary goal of the article is to examine whether incumbent tenure amplifies or attenuates economic voting and to propose a plausible explanation for this pattern. Accordingly, I recognize that the conclusions drawn in this section remain tenuous, and that I cannot be certain as to why incumbent tenure decreases with time in office.

Conclusion

This article has provided a thorough empirical investigation of the long-term relationship between economic voting and time in office. I have shown that electoral support for executive parties becomes more independent of the economic situation the longer they have been in office. I arrived at this finding using two markedly different datasets: one at the country level using objective measures of economic conditions, and one at the individual level using subjective measures.

To explain why economic voting decreases as incumbents' time in office increases, I advanced a theoretical argument predicated on Bayesian learning. It follows from Bayesian learning that if voters have more relevant information about an incumbent's competence, then their evaluation of the incumbent is less likely to be swayed by a single piece of new evidence, such as the economic situation around election time. Conversely, if voters have less prior information, they will be more heavily influenced by the economic situation around election time. Since voters naturally accumulate relevant information about the incumbent as his or her time in office increases, Bayesian learning implies that economic voting should decrease with time in office.

In order to examine the empirical implications of this theoretical argument in greater detail, I conducted an additional study of subnational elections. Specifically, I studied the level of local economic voting following a large redistricting reform in Denmark. This reform created within-municipality differences in the amount of experience the electorate had with the same incumbent mayoral party. In line with my theoretical argument, I found that voters who had less experience with a local incumbent were more likely to punish this incumbent for increases in local levels of unemployment.

Turning to limitations, this article has mainly studied advanced European parliamentary democracies, delimiting the scope of inference. This focus on relatively stable political systems might partly explain why my findings diverge from previous research, which has tended to study less stable presidential systems (Singer and Carlin Reference Singer and Carlin2013). In particular, political instability will lead to shorter stints in office, and this might change the overall relationship between time in office and economic voting. Another important limitation relates to why economic voting decreases with time in office. As mentioned in the discussion of alternative explanations, the evidence supporting the Bayesian learning explanation is far from definitive; other factors, most prominently confirmation bias on the part of the voters, might also have a role to play. Future research might be able to pin down the causal mechanisms underlying the relationship between time in office and economic voting by exploring the relationship in more controlled experimental settings (for example, Besley and Case Reference Besley and Case1995).

As discussed above, incumbents are likely to be more responsible for the state of economic conditions as their time in office increases. Following the large and empirically successful literature on clarity of responsibility, one would expect incumbents to be held more accountable for their economic performance as their time in office increased. However, the results suggest that other factors, like Bayesian learning, more than offset any potential increases in clarity of responsibility. In this way, my findings challenge selection models that privilege the signal-to-noise ratio in the economy as the key variable determining the size of the economic vote (Duch and Stevenson Reference Duch and Stevenson2008). Sometimes voters rely more on weaker signals of government performance. Future models of the economic vote should take this into account, perhaps by directly incorporating Bayesian learning.

The findings in this article also challenge the idea that economic voting is a form of ‘blind retrospection’, in which voters lash out at the incumbent simply because they are in distress. Instead, this study suggests that voters primarily reward and punish the incumbent for recent economic conditions if they have little other relevant information available. Of course, this does not imply that voters are especially reasonable in how they hold the incumbent responsible for economic conditions, but it does imply that voters are selective in how they pass electoral judgment on the economy.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Bernard Grofman, Eric Gunterman, Robert Klemmensen, Lasse Laustsen, Gabriel Lenz, David Dreyer Lassen, Kasper Møller Hansen, Austin Hart, Michael Lewis-Beck, Richard Nadeau, Rune Stubager, seminar participants at Université de Montréal, University of Copenhagen, American Political Science Association Annual Meeting 2015, Midwest Political Science Association 2019 and seven anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. For diligent research assistance I would like to thank Winnie Faarvang and Camilla Therkildsen.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/EB1T26 and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123419000280.