An increasing amount of research on foreign aid stresses the role of public opinion in donor countries as key to explaining complex decision making regarding foreign aid.Footnote 1 Recent theories see citizens in donor countries as driven by a moral impetus, and explicitly assume that care and concern for others push people to support aid to poor countries and disapprove of giving aid to unsavory regimes.Footnote 2 Other work is less direct about these assumptions. When scholars assume that the donor government wants aid to have a positive impact on development and welfare, the implicit assumption seems to be that a non-trivial subset of citizens in the donor country embraces this moral dimension of aid.Footnote 3

Theories’ predominant focus on the moral dimension of people’s preferences, however, runs counter to our existing knowledge on public opinion in foreign policy generally: people do not single-mindedly use a moral yardstick to evaluate foreign policy. Recent experimental findings demonstrate that voters also care about material benefits and the consequences of foreign policies, ranging from immigration and trade policy to economic sanctions and the use of military force.Footnote 4, Footnote 5 The possibility that material concerns coexist with moral ones further complicates the task of theoretically identifying citizens’ preferences over policy choices. Multidimensionality allows for trade-offs, after all. If public opinion truly holds the key to explaining donors’ policy choices, it is important to understand citizens’ trade-offs involved in pursuing these goals.

Drawing on these insights, we develop and study more complex micro-foundations behind public opinion over aid policy. As a first step in this larger enterprise, we focus on how citizens see foreign aid policy toward nasty regimes, such as those that abuse human rights, foster corruption and rig elections. Aid policy toward such regimes presents an excellent case for evaluating trade-offs. On the one hand, public discussions demonstrate that people believe aiding such regimes is morally unacceptable as it signifies complicity in promoting harmful policies.Footnote 6 On the other hand, substantial aid flows to such unsavory countries, presumably because they generate policy concessions from the recipient in return for aid.Footnote 7 By studying how citizens evaluate aid to these nasty regimes, we seek to assess not only the depth and limits of people’s moral sentiments, but also how they interact with the pursuit of instrumental benefits and determine the policy that people prefer their government to take.

We theorize about trade-offs between moral and material considerations, and design and implement a survey experiment to evaluate them empirically. We use side-by-side comparisons of aid allocation scenarios in which we randomly vary multiple attributes, including the obtained policy concessions from the recipient, potentially morally offensive policies pursued by the recipient government and how the donor government can deal with these. The unsavory policies in our study include human rights abuses, theft of aid, crackdowns on media outlets and electoral fraud by the recipient country. These complex scenarios allow us to study the various trade-offs between the instrumental and moral dimensions of foreign aid policies that citizens may consider. Our survey was taken by 2,217 US-based subjects in the summer of 2014. Using this survey experiment, we show that people value the morally guided as well as the political use of aid. Importantly, moral concerns carry far more weight, supporting one aspect of the conventional view.

We go a step further and study what these trade-offs imply about the public’s preferences on policy toward nasty regimes. Donor governments can (and do) design different features of aid policy in a way that may offset the (expected) negative reaction from their citizens when a scandal or news coverage highlights the unpalatable policies. We introduce three such remedial policies and study whether and how these policy strategies by the donor government change citizens’ evaluation of aid. First, we examine the strategy commonly assumed in prior research on human rights and foreign aid:Footnote 8 by simply giving less aid, the donor can distance and disassociate itself from the nasty policies of the recipient. However, our experiment shows no evidence that this policy helps to reverse citizens’ negative reaction to unsavory regimes. Secondly, the donor government can pair information about the specific policy concessions in exchange for aid to lessen concerns about aid going to an unpalatable regime; the government would effectively divert attention away from the unsavory polices. Our results show that this works in some situations but is fairly ineffective overall.

Thirdly, citizens may find giving aid to nasty recipients to be more acceptable when their own government engages more with the recipients and specifically addresses the unpalatable issue. For example, when a recipient rigs elections, citizens might have fewer quarrels with the whole aid package when additional funds go toward election monitoring. Our strongest and most consistent results support the predictions of this last strategy. Across unsavory issues, donors fare better addressing the issue than ignoring it. The remedial effect of addressing is most pronounced when the issue is human rights violations by the recipient regime. Support drops by 3.8 points [3.3, 4.3] on a nine-point scale when the donor government fails to address the issue;Footnote 9 however, the drop is only 2.4 [1.7, 3.0] points when optimally addressed by giving more aid.

At a more fundamental level, our findings provide a public opinion-based answer to why and how democratic donors continue to provide a large sum of foreign aid to nasty regimes. The conventional explanations of this puzzle rely on two stylized types of donors, the Samaritan and the bribe payer. The former is altruistic and focuses its aid on unsavory regimes to help those in dire situations. The latter type provides aid to nasty recipients because they tend to be the optimal target to bribe for concessions.Footnote 10 One problem with either type of donor is that their voters abhor giving aid to such regimes, as we will show. Our results suggest that, regardless of whether one conceives of donor governments as selfless, selfish or some mixture thereof,Footnote 11 donor governments routinely use these remedial policies.

In the next sections, we develop our ideas about the interplay of public preferences over aid, governments’ incentives and potential policies in greater detail. Then we introduce the conceptual ideas in the survey design, and subsequently describe the operationalizations and the analysis. We conclude by discussing several implications for wider issues in the aid literature. These include the fragmentation of aid, the channel of delivery and the effectiveness of specialized aid, and we suggest that future work should explore donor governments’ public relations efforts.

MORAL PUBLIC PREFERENCES OVER FOREIGN AID

The aid literature has a long tradition of attempting to understand donors’ motives and preferences. Since early on, scholars have interpreted correlations between aid and covariates to determine whether donor interests or the ‘needs’ of recipients drive aid allocations.Footnote 12 However, evidence that either motive is clearly more applicable has long been elusive.Footnote 13 Scholars have recently shifted their attention toward developing theoretical models that encompass multiple actors and motives, and in particular engage the domestic political dynamics in the donor country. Two assumptions are widespread in the literature. First, donor governments prefer using foreign aid to obtain any kind of policy concession from recipients. Secondly, donor citizens view foreign aid as a tool to help those under duress in poor countries. Scholars assume that such moral motivations push voters to favor more aid to poor countries and prefer to eschew corrupt, repressive regimes.

These conflicting preferences over the purposes of aid play a central role in recent theorizing. In democracies, the government minimizes its parochial policy preferences by and large and represents the preferences of its constituents if the anticipated electoral consequences of ignoring the constituents are serious. One implication is that when citizens are informed about foreign policy, policy becomes more congruent with the moral public preferences. In this vein, scholars show why donors respond haphazardly when natural disasters and human rights violations harm people.Footnote 14 They theorize that if either becomes prominent in the news, donors demand to give more aid in the case of natural disasters and to withdraw it when human rights violations are perpetrated. When voters are not informed, donors do not respond. Another example of such citizen–government tension is Milner’s study of multilateral aid allocations.Footnote 15 She theorizes that donor governments delegate aid to international organizations (IOs) as a way to deflect skepticism among their development-minded voters over the potential instrumental use of aid.

However, these new theories may stand on shaky ground. In particular, the prevalent assumption that people are only morally orientated is restrictive and actually at odds with the recent literature on foreign policy preferences. For example, people also care about outcomes, effectiveness and their personal benefits from policies.Footnote 16 More broadly, Jentleson suggests that people are ‘pretty prudent’ and less single minded than assumed in the aid literature reviewed above.Footnote 17 More importantly, if we adopt a richer set of preferences (for example, material and moral concerns), it is no longer clear what policy options citizens favor. For example, less aid to nasty regimes may soothe people’s moral concerns but is bound to negatively affect the pursuit of instrumental goals. Similarly, while channeling more aid through multilateral institutions may reassure citizens that aid is used for developmental goals, this shift would also lead to less control over aid and thus fewer tangible benefits from aid. In the next section we develop more policy options, some of which have been prominently studied in the context of other foreign policies. We propose to take a step back and develop from scratch the assumptions about individual preferences in the context of foreign aid first. Then, we can examine the broader consideration of how donors can manage the morality–benefits trade-offs.

PEOPLE’S PREFERENCES AND FOREIGN AID

To examine complex preferences on foreign aid, we focus on how citizens evaluate aid policy toward ‘nasty’ regimes. In particular, we examine several policies pursued by recipient governments, such as torture, theft of aid, crackdowns on media outlets and electoral fraud. We focus on nasty regimes and these policies because aiding such regimes should have clear moral implications for donor citizens, as described below in more detail.

We begin by assuming that people’s attitudes toward a policy are a function of beliefs about the policy’s attributes. Furthermore, we assume that people anticipate and evaluate consequences on multiple dimensions and attach different degrees of saliency to each of them. In particular, we assume two such dimensions: morality and tangible returns from foreign aid to the recipient (that is, policy concessions).

First, we expect moral considerations to be important for citizens to form policy preferences. By morality, we mean caring for others and protecting them from harm. Aiding nasty regimes that pursue policies like torture, theft of aid and electoral fraud is likely to have moral implications as these policies have clear, direct and negative impacts on the welfare of citizens within nasty regimes. In addition, donor citizens may believe that providing financial support to unsavory regimes renders them complicit in the wrongdoing.Footnote 18 These moral implications of aiding unpalatable regimes lead us to expect that the donor public disapproves of aid to these countries. This has been central to existing work on foreign aid allocation.

Secondly, we also contend that citizens’ support for aid policy depends on evaluations of the material consequences. While foreign aid is often viewed as a form of charity, it is well known that donor governments often use aid to obtain economic and security benefits for their citizens.Footnote 19 In many ways, foreign aid is just like any other foreign policy in that it should bring (some) benefits to at least a non-trivial number of citizens.Footnote 20 Thus we also assume that citizens prefer to give aid to a regime that provides tangible benefits in return.

If our assumptions about how people view the moral and material dimensions are correct (which our survey experiments will confirm), then the best aid practice from the voters’ perspective would be to give aid to countries with democratic regimes (which tend to be less nasty) that in turn provide lavish policy concessions. However, this is bound to be wishful thinking, as democratic recipient governments cannot provide policy concessions cheaply.Footnote 21 Thus if policy concessions are of interest, donors will turn to autocracies – the countries most heavily engaged in nasty policies.Footnote 22 As people’s desiderata cannot be catered to simultaneously, a donor government has to design a policy that remedies aspects of this dilemma. We develop and consider three such possible options: distancing, diverting and addressing.

The first strategy we consider is the one commonly assumed by previous work,Footnote 23 which we call distancing. When voters disapprove of aid to a particular regime, the donor government is assumed to satisfy voters by withdrawing aid to the recipient regime. As aid often signifies support and a stamp of approval for the recipient,Footnote 24 one simple tactic is to weaken ties with the nasty regime. Despite its intuitive appeal, this strategy may not be optimal from the citizens’ perspective. On the one hand, distancing addresses moral concerns as aid cuts lead to less engagement and support to the nasty regime. On the other hand, it brings material benefits to a halt. Since aid giving serves political purposes, its withdrawal would result in lost opportunities to maintain a mutually beneficial relationship with an important state.Footnote 25 Thus we expect that distancing should have an ambiguous effect on citizens’ overall support for aid policy.

Secondly, we posit that donor governments could attempt to divert the public’s attention from the recipients’ nasty policies and thus not have to give up the policy concessions.Footnote 26 Voters’ concerns about the recipients’ unpalatable policies can be diverted by emphasizing the policy concessions from the recipient. The logic behind this strategy is related to that of framing. Numerous experiments by behavioral scientists demonstrate that subjects’ policy preferences are strongly affected by how particular aspects of policy are presented and emphasized.Footnote 27 Such framing effects are particularly pronounced when the issue is complex and people have little expertise, a situation that cogently describes foreign aid policies from a citizen’s perspective. Indeed, governments engage in deliberate framing of foreign aid, talking up its benefits for the economy, security, or as a national duty on websites and across social media.Footnote 28 We argue that diverting can be an effective means of managing the public’s moral concerns while not jeopardizing the receipt of material benefits. More concretely, diverting would affect citizens’ attitudes by increasing the saliency of material benefits while reducing the saliency of moral concerns. Thus we expect that greater policy concessions would mitigate voters’ moral concerns.

Thirdly, we introduce another remedial strategy that directly tackles the moral valuation. We take inspiration from the observation that foreign aid often comes as discrete projects that are ostensibly designed to address specific issues in the recipient country, ranging from improving the handling of judicial matters to demographic forecasting, from tuberculosis control to reforming human rights practices and the administrative quality of elections.Footnote 29 Given that some of these purposes are closely related to the nasty issues discussed here, we argue that citizens perceive funding for such specialized projects favorably as an attempt to address, and perhaps solve, the underlying offensive issue in the recipient country. For example, if a recipient is rigging its elections, then the donor government may provide funds to notable international and non-governmental organizations (IOs/ NGOs) with a reputation for monitoring electoral fraud. That is, aid is given in addition to the money that pays for the policy concession.Footnote 30 While this strategy costs more for the donor (which ought to be disliked), citizens may view it more favorably. The addressing strategy not only mitigates people’s moral concerns by funding to solve (eventually) the offensive issue, but also allows people to continue obtaining material benefits from recipient countries. Thus, we expect that addressing would lessen the public’s discontent from learning that aid goes to a country that pursues nasty policies.

Our elaboration of preferences leads us to the following expectations. As a first step, we investigate the extent to which people’s support for foreign aid depends on concerns over instrumental goals and moral concerns for the recipient. Secondly, we test whether the three remedial strategies – distancing, diverting and addressing – can moderate citizens’ moral concerns.

EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN

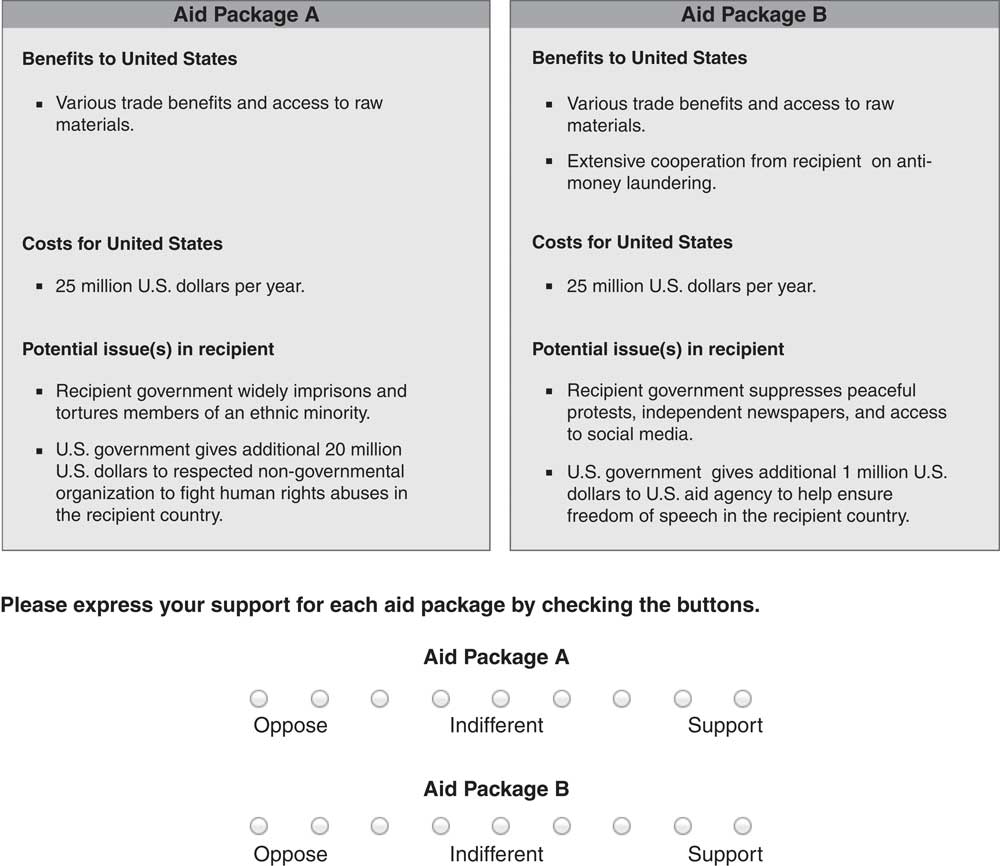

In this section, we introduce a survey experiment designed to test our arguments about moral and instrumental goals as well as donor government policy. We use a side-by-side comparison of two hypothetical aid packages that Hainmueller, Hangartner and Yamamoto suggest captures the real-world phenomenon of interest.Footnote 31 Each aid package contains and randomizes information about costs and benefits as well as other background information, including the pursuit of nasty policies and remedial funds (for the addressing policy). Below each pair, we ask the respondent to ‘express [his/her] support for each aid package by checking the buttons’. The rating options range from ‘Oppose’ to ‘Support’ along nine possible levels. Each respondent is shown four such screens in succession to evaluate. Figure 1 shows a representative screen.

Fig. 1 Representative example of screenshots of the survey experiment

Each foreign aid package contains four manipulations reflecting the four variables required to test our expectations: some baseline cost of the aid package, benefits that foreign aid helps attain (that is, the policy concessions), information about potentially unpalatable policies pursued by the recipient regime, and possible actions that the government can take to address these recipient’ policies. We explain each of these in turn.

Under ‘Benefits to United States’, we vary how much policy benefit foreign aid brings about for the donor country. This manipulation helps us show how much voters like or dislike the political use of foreign aid, and lets us study whether such benefits can help divert respondents’ ire when the recipient pursues unsavory policies. All cases have a baseline benefit specified as ‘various trade benefits and access to raw materials’. Randomly, a specific policy concession is added, either ‘minor’ or ‘extensive’ co-operation from the recipient on ‘counter-terrorism’ (CT) or ‘anti money laundering’ (AML). While this is not an exhaustive list of benefits that foreign aid can buy, we chose these for two reasons. First, since co-operation on counter-terrorism and anti-money laundering is not related to development objectives, it nicely captures the idea of policy concessions in the form of public goods to the donor populace. Secondly, co-operation on counter-terrorism ought to be particularly salient to our respondents, which perhaps gives us a sense of how large the appreciation of benefits can be. This results in five possible instrumental benefits.

Next, we randomize under ‘Costs for United States’ the costs of the hypothetical aid packages: 25, 50 and 75 million US dollars.Footnote 32 These costs are intended to capture the base amount of foreign aid going to the recipient country, allowing us to investigate whether distancing by the government mitigates the public’s moral concerns. As we argue above, less extensive ties (that is, less aid) with a regime that pursues unsavory policies should vex respondents less.

To examine the extent to which public support for aid depends on moral concerns, we consider four unpalatable policies by the recipient. First, corruption in general and the theft of aid flows are a recurring issue in development debates. Theft of aid implies that aid does not reach its ostensible targets, namely the impoverished, but instead goes to politicians. The cases of politicians such as Indonesia’s Suharto, the Philippines’ Ferdinand Marcos and Zaire’s Mobutu Sese Seko, who enriched themselves while most of their countries lived in poverty, are centerpieces of aid critiques.Footnote 33 Secondly, good governance and political accountability have become important in discussions of development.Footnote 34 Elections that are rigged or undermined by the incumbent’s forces fail to square with the crux of elections. Citizens in the donor country should see them as important norms to uphold.Footnote 35 Thirdly and similarly, the availability of news sources to learn about politics and to co-ordinate around elections is crucial to functioning democracy processes. Therefore, interference with media services by the recipient government should also be viewed as unpalatable. Lastly, human rights abuses such as torture or political imprisonment on the basis of religion and ethnicity are arguably the most obviously and overtly nasty policies that an aid recipient can pursue. Ample literature, as discussed above, makes the link between aid and human rights. These four potentially objectionable policies by recipients are common concerns in the study of development, and we expect citizens in the donor country to disapprove of providing aid to regimes pursuing such policies.

We translate these concepts about unpalatable policies into the survey experiment as follows. Under ‘Potential issue(s) in recipient’, we randomly insert one of the following six into the vignette. The first leaves blank the space in which an issue might be listed, indicating no unpalatable policy is pursued. The second captures a placebo treatment and states the athletes from the recipient country scored an unexpected victory against US athletes in the last Olympic Games.Footnote 36 The next four exhibit the potential recipient’s unsavory policies: ‘Recipient politicians frequently steal money from development aid’, ‘Recipient government systematically manipulates elections in its favor’, ‘Recipient government widely imprisons and tortures members of an ethnic minority’ and ‘Recipient government suppresses peaceful protests, independent newspapers, and access to social media’.

Last, we study the idea that the donor government can address the offending issue in the recipient country. We focus on two salient features of this policy. First, we examine how the amount of funding for such projects affects the public’s attitudes. The public may perceive directing too little aid to addressing problems as ineffective, but providing too much may appear wasteful as we also argued that costlier aid is less appreciated. Thus we examine how citizens’ attitudes respond to changes in the amount of this remedial measure. Secondly, we also vary the channel of delivery of this extra aid. Drawing on the recent literature that focuses on variation in aid delivery channels,Footnote 37 we study the possibility that voters’ attitudes may change depending on which actor directly addresses the underlying issue. We focus on the governmental aid agency, NGOs and IOs, covering the major channels used by actual donors.

If one of the unpalatable policies is drawn (aside from the placebo) for a vignette, we randomly assign how the US government addresses the issue. Either it ignores it, in which case the bullet point for a remedy remains blank, or it proposes additional aid aimed at addressing the issue. The language for the latter is: ‘US government gives additional Amount million U.S. dollars to Agency to Goal in the recipient country’, where the variables Amount ∈ {1, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25}, Agency ∈ {US agency, respected non-governmental organization, respected international organization} and Goal ∈ {help solve corruption issues, ensure free and fair elections, fight human rights abuses, help ensure freedom of speech}. Goal is automatically matched to the randomly drawn issue.

These packages capture many of the essentials of governments’ foreign aid policy choices: costs, benefits, aspects of the targets’ and governments’ attempts to deal with potentially unpalatable issues. All these fully randomized aspects are evaluated jointly, and we will disentangle the causal interactive effects within the evaluations.Footnote 38

Administration of Survey

We recruited subjects via Amazon’s MechanicalTurk (MTurk) between 5–9 August 2014. After accepting the task, participants (n = 2,217) were directed to a page on one of the authors’ websites.Footnote 39 As each subject sees four side-by-side comparisons, we have 2,217×4×2=17,736 evaluations.Footnote 40

Statistical Analysis

In order to evaluate our various expectations, we rely on four linear regression models. We define our outcome variable Y as a measure of support for foreign aid (a nine-point scale in which higher values indicate greater support levels). We include in our first specification a series of indicator variables representing each level of the recipients’ potential issues, benefits from aid giving and baseline costs, which we denote by P, B and C, respectively.Footnote 41 Specifically, Equation 1 represents our first model (suppressing subscripts):

where I(·) is the indicator function, which takes a value of 1 if the condition in the parenthesis is true, and 0 otherwise.

To examine whether the distancing strategy moderates the voters’ moral concerns, we extend the first model by adding interactions between the cost dummies and the potential issues. This gives us our second model:

$$\eqalignno{ Y\,{\equals}\, & \beta _{0} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq j\leq 3} {\beta _{{1j}} I(C{\equals}c_{j} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq k\leq 5} {\beta _{{2k}} I(B{\equals}b_{k} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq l\leq 6} {\beta _{{3l}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} )} } } \cr & {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{\scriptstyle 2\leq j\leq 3 \hfill \atop \scriptstyle 3\leq l\leq 6 \hfill} {\beta _{{4jl}} I(C{\equals}c_{j} \wedge P{\equals}p_{l} ).} $$

$$\eqalignno{ Y\,{\equals}\, & \beta _{0} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq j\leq 3} {\beta _{{1j}} I(C{\equals}c_{j} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq k\leq 5} {\beta _{{2k}} I(B{\equals}b_{k} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq l\leq 6} {\beta _{{3l}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} )} } } \cr & {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{\scriptstyle 2\leq j\leq 3 \hfill \atop \scriptstyle 3\leq l\leq 6 \hfill} {\beta _{{4jl}} I(C{\equals}c_{j} \wedge P{\equals}p_{l} ).} $$

If distancing is effective, we should find that the effects of the unpalatable issues are smaller when the baseline cost is small rather than high. That is, in Equation 2, we expect that the effect of unsavory policy l when the cost is $75m (β 3l +β 43l ) is smaller than when it is $50m or $25m (β 3l and β 3l +β 42l , respectively).

The third model is used to examine the effects of diverting. We modify the first model by interacting all benefits with all issues but the placebo:

$$\eqalignno{ Y\,{\equals}\, & \delta _{0} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq j\leq 3} {\delta _{{1j}} I(C{\equals}c_{j} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq k\leq 5} {\delta _{{2k}} I(B{\equals}b_{k} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq l\leq 6} {\delta _{{3l}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} )} } } \cr & {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{\scriptstyle 2\leq k\leq 5 \hfill \atop \scriptstyle 3\leq l\leq 6 \hfill} {\delta _{{4kl}} I(B{\equals}b_{k} \wedge P{\equals}p_{l} ).} $$

$$\eqalignno{ Y\,{\equals}\, & \delta _{0} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq j\leq 3} {\delta _{{1j}} I(C{\equals}c_{j} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq k\leq 5} {\delta _{{2k}} I(B{\equals}b_{k} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq l\leq 6} {\delta _{{3l}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} )} } } \cr & {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{\scriptstyle 2\leq k\leq 5 \hfill \atop \scriptstyle 3\leq l\leq 6 \hfill} {\delta _{{4kl}} I(B{\equals}b_{k} \wedge P{\equals}p_{l} ).} $$

If the diverting strategy mitigates the moral concerns, we expect that the effects of nasty issues decrease with higher values of benefits. In Equation 3, we are specifically interested in δ 3l +δ 4kl for issue l.

Last, we use the fourth model to study the addressing strategy by extending the baseline in the following ways. First, we add the interactions between the issues and the linear term of the additional aid, which is denoted by R, for each channel of delivery denoted as D.Footnote 42 These are in essence triple interactions, which allow channels to have different effects depending on the issue. Secondly, we add another set of interactions between the issues and no remedial aid (R=0). It is important to include these as well because they allow us to estimate the effect of ignoring the issues in the recipients separately.Footnote 43 Thus mathematically, our fourth model is specified as:

$$\eqalignno{ Y\,{\equals}\, & \gamma _{0} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq j\leq 3} {\gamma _{{1j}} I(C{\equals}c_{j} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq k\leq 5} {\gamma _{{2k}} I(B{\equals}b_{k} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq l\leq 6} {\gamma _{{3l}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} )} } } \cr & {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq l\leq 6} {\gamma _{{4l}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} \wedge R{\equals}0){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{\scriptstyle 3\leq l\leq 6 \hfill \atop \scriptstyle 1\leq m\leq 3 \hfill} {\gamma _{{5ml}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} \wedge D{\equals}d_{m} ){\times}R} } $$

$$\eqalignno{ Y\,{\equals}\, & \gamma _{0} {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq j\leq 3} {\gamma _{{1j}} I(C{\equals}c_{j} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq k\leq 5} {\gamma _{{2k}} I(B{\equals}b_{k} ){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq l\leq 6} {\gamma _{{3l}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} )} } } \cr & {\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{2\leq l\leq 6} {\gamma _{{4l}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} \wedge R{\equals}0){\plus}\mathop{\sum}\limits_{\scriptstyle 3\leq l\leq 6 \hfill \atop \scriptstyle 1\leq m\leq 3 \hfill} {\gamma _{{5ml}} I(P{\equals}p_{l} \wedge D{\equals}d_{m} ){\times}R} } $$

In Equation 4, γ 5ml ×R captures how R amount of additional aid through delivery channel m conditions the effect of issue l while γ 4l represents the effect of ignoring the issue by giving no additional aid. Thus to study whether addressing moderates the effects of the issues, we compare γ 5ml ×R and γ 4l for issue l.

When using the first three models to study the effects of issues and benefits as well as the distancing and diverting strategies, we drop all observations in which some addressing occurs (that is, any with R>0). We do this to keep the analysis simple so that we do not have to account for any remedial aid (R); the results do not change when we include all the observations. This leaves us with 4,975 evaluations for the first three models. When we study addressing via Equation 4, we use all the observations.

Respondents from MTurk do not represent a random sample of the US population, as is well known. While the experimental manipulation guarantees internally valid treatment effects, these estimates are only representative of the population if treatment effect homogeneity holds. We believe that it is unlikely to hold, but have no theoretical or empirical guidance for how big this heterogeneity ought to be. Thus we reweight our sample to match several demographic characteristics of a known nationally representative survey.Footnote 44 Our survey experiment includes numerous questions from the 2012 Cooperative Congressional Election Study (CCES),Footnote 45 and we use entropy balancing and create weights for our own data so that several covariates’ moments match those of the CCES data.Footnote 46 Our preferred weights come from a complex set of variables to capture a variety of sources of heterogeneous treatment effects: age, gender, whether one had four years of college and beyond, a linear version of an ideological self-assessment, whether the respondent has a full-time job, and whether life has got worse or much worse recently.Footnote 47 Appendix Figure A.10 shows that entropy balancing removes the large imbalances in the raw data.Footnote 48

Before proceeding, we want to address the generalizability of our US-based results to other major donor countries. While there are differences in the level of public support for aid across donor countries,Footnote 49 the heterogeneity of individual-level effects need not necessarily be noteworthy. In a rare effort examining this issue, Heinrich, Kobayashi and Bryant report that individual (parochial) pocketbook effects on support for aid are not unusual for the United Kingdom compared to those of other European Union states.Footnote 50 This is noteworthy, as the United Kingdom is often portrayed as a stalwart for effective aid. While surely there will be differences in the magnitude of effects across countries, it is not obvious why the fundamental logic behind trade-offs between the moral and instrumental goals behind aid should be absent or reversed elsewhere. That said, we hope future studies will replicate (elements of our) study in other countries to gain confidence in the generalizability of our results.

Last, given that each respondent rates numerous packages, intra-subject correlations are expected. We account for these by estimating the variance–covariance matrix of the sampling distribution via a cluster bootstrap, which we use for the parametric bootstrap to calculate uncertainty for the estimates.Footnote 51

RESULTS

We first examine the unconditional results regarding how moral and political concerns affect public attitudes about aid giving, and how much costs matter.Footnote 52 We then examine the three proposed policies that might mitigate the public’s moral concerns.

Political and Moral Concerns

Of particular initial interest to us are the treatment effects of the benefits and the unpalatable policies in the recipient country, presented in Figure 2. We use dots to represent median estimates and horizontal lines to indicate the 95 per cent confidence intervals for the treatment effects. The effects should all be interpreted in comparison to the reference levels: the baseline benefits of ‘various trade benefits and access to raw materials’ for the benefits and no issues for the recipient’s unpalatable policies.

Fig. 2 Effects of benefits, potential issues, and cost of aid Note: the x-axis presents the coefficient estimates for each variable on the y-axis. The presented effects correspond to all estimates of α 1j , α 2k , and α 3l in Equation 1. The dot denotes the median estimate, and the horizontal lines the 95 per cent confidence intervals. All regression coefficients for the model are shown in Appendix Figure A.3.

The results provide support for the claim that voters evaluate foreign aid on moral grounds. Consider the effects of the recipients’ issues, shown in the lower part of Figure 2. First, it is noteworthy that the placebo is negative and statistically indistinguishable from zero. Merely presenting an issue unrelated to aid and development already lowers respondents’ appreciation of the aid policy by −0.7 [−1.0, −0.3]. However, the placebo effect is much smaller than the effects of aid theft (−2.3 [−2.8, −1.7]), rigged elections (−2.4 [−3.1, −1.6]), media crackdown (−2.3 [−3.0, −1.6] and torture (−3.5 [−4.0, −3.0]). Perhaps unsurprisingly, torture elicits the greatest disapproval. It is thus the case that citizens strongly disapprove of providing aid to regimes with unpalatable policies, which replicates Allendoerfer’s basic finding.Footnote 53

The survey respondents also appreciate greater benefits that come from giving aid. Looking at the lower part of Figure 2, respondents appear to be indifferent or even slightly negative about small benefits (that is, minor co-operation from recipients) in comparison to simply obtaining the baseline benefits. Major co-operation on anti-money laundering is appreciated, but not strongly so. Co-operation on counter-terrorism fares better. An extensive concession on fighting terrorism increases support by 0.5 [0.0, 1.0]. Further, and unsurprisingly, people like aid less as it grows more expensive. Compared to a cost $50m, aid at $75m reduces support by 0.5 [0.1, 0.9]. If costs fall to $25m, support increases by 0.4 [0.0, 0.8]. This corroborates (broadly) the pocketbook effects of aid that Heinrich, Kobayashi and Bryant report.Footnote 54

The first batch of results suggests dual motives in voters’ evaluation of foreign aid policy. Voters not only want to see foreign aid used in a moral way; they also appreciate (some specific) benefits obtained by aid giving. However, Figure 2 also shows that the negative effects of the recipients’ unpalatable policies are much larger in magnitude than those of the benefits of aid giving, substantiating the often-made claim that voters see foreign aid mainly through a moral lens.

Thus when the donor government designs aid policy and aims to prevent alienating the public, it needs to consider what is taking place in the recipient country. That is, the worst that can happen to public support for a donor’s aid policy is the policy pursued by the recipient country. Since the donor government also wants policy concessions mainly from countries that are most likely to pursue such policies, donors should often be at an impasse.

Effectiveness of Three Remedial Actions

Next, we test how distancing, diverting and addressing can moderate the negative effects of recipients’ unpalatable policies on the rating. More specifically, we are interested in how the costs of aid packages, the benefits of aid giving and the funding of specific projects change the effects of the unpalatable policies.

Figure 2 shows the effects of recipients’ morally offensive policies on subjects’ ratings conditional on the costs of aid packages and the benefits of aid giving. First, consider the top panel in Figure 2 for the results of the distancing strategy. The y-axis shows the conditional effects, whereas the x-axis lists all the unpalatable policies as well as the placebo. Each of the vertical lines (and their respective dots) indicates the effect of the issue listed on the x-axis conditional on aid costing $25m, $50 and $75m, from left to right. Contrary to what is assumed in the existing theories, the results show that lower levels of aid (that is, less entanglement) do not consistently reduce public moral concerns over unsavory policies. For example, the effect of torture is −3.2 [−4.1, −2.4] when the cost of aid is $75m. If cutting the extent of aid successfully distances the donor from the recipient’s policy, then the effect should become less negative when costs are $25m or $50m. However, the disapproval increases in magnitude (to −3.8 [−4.6, −3.0] and −3.4 [−4.2, −2.8], respectively). Across all policies, no consistent evidence emerges.Footnote 55

The second strategy we examine is diverting, which is shown in the bottom panel of Figure 3. We expect the effects of unpalatable policies to decrease as more benefits are attained from giving aid. The results show some, but no consistent, mitigating effects from diversion. While most differences are indeed positive, some actually make the evaluation worse, and only one policy benefit out of sixteen cases significantly reduces citizens’ disapproval: small anti-money laundering benefits can undo some of the disapproval from the recipient rigging elections.

Fig. 3 Effects of unpalatable policies conditional on distancing and diverting Note: the y-axis presents the conditional effects of unpalatable policies of recipients, whereas the x-axis represents all the recipient’s issues. These correspond to the estimates of β 3l +β 42l , β 3l , and β 3l +β 43l (from left to right) in Equation 2; those of δ 3l +δ 42l , δ 3l +δ 43l , δ 3l +δ 44l , δ 3l +δ 45l (from left to right) in Equation 3. The vertical lines and dots indicate the 95 per cent confidence intervals and the median estimates. Each separate vertical line shows a different remedial policy. The coefficients themselves are shown in Appendix Figures A.4 and A.5.

Finally, we investigate the addressing strategy. We first discuss how we show our results. Channeling additional aid through one’s own agency, an NGO or an IO and choosing how much to fund are largely under the donor government’s discretion.Footnote 56 That is, the donor government optimizes this and does not randomize the channel and the funds like we have done in the vignette. Therefore, it is not enlightening for our purposes to consider all possible responses in great detail (that is, every level of remedial aid via all three channels for each issue). Rather, we want to focus on the optimal combination of additional aid and channel. Using our statistical model (Equation 4), we simulate the best government response for each issue (that is, the one that minimizes the respondent’s ire from the unsavory policy). We search the space of $0–25m extra aid that is given via one delivery channel for every draw of the parametric bootstrap, which provides the entire distribution of best responses for each potential issue.Footnote 57

Figure 4 shows the effects of nasty policies on support, conditional on the optimal remedial aid to address each issue. The darker lines and dots show the effects when the government stands idly by and gives aid to a regime pursuing the unsavory policy listed on the x-axis; the lighter variants show the effects when the optimal amount of aid and channel of delivery is chosen.

Fig. 4 Effects of unpalatable policies conditional when the government optimally addresses Note: the y-axis presents the conditional effects of unpalatable policies of recipients, whereas the x-axis represents all the recipient’s issues. The vertical lines and dots indicate the 95 per cent confidence intervals and the median estimates. The coefficient estimates are shown in Appendix Figure A.2.

Unlike the distancing and diversion strategies, these results consistently show that the effects of unpalatable policies significantly improve when the government applies the best responses. For every issue aside from stolen aid is the 95 per cent confidence interval of the difference between the optimally tackled issue and the unremedied issue positive. The improvements are also quite strong in magnitude. Take the rigged elections, for example. When the rigged elections remain unaddressed by the donor, public support reduces by 3.7 [2.3, 6.6] times the effect size of the placebo. When the donor optimally bundles the remedial aid, this effect falls to only 2.0 [0.9, 3.9] times the placebo size. The effects are also pronounced for torture, which is the issue that elicits the most negative response. The reduction in support is 5.7 [3.6, 10.8] times the placebo when the government stands idly by, but shrinks to 3.5 [1.9, 6.5] times the placebo effect if the government optimally addresses the torture issue.

We wish to take these results a step further. So far, we have left the specific channel of delivery in the background as we have focused on the best response that the government can choose. Unlike in this survey experiment, reality should constrain donors (somewhat) in their choice of the channel of delivery; the optimal IO or NGO might be reluctant to accept government funds, or be unwilling to engage in the particular recipient country. Therefore, we also examine whether the donor can significantly lower citizens’ malcontent through each of the three channels. Appendix Figure A.9 shows for every issue and for every delivery channel the difference between the effect of the issue when optimally choosing the remedial aid and the effect when the issue is left unaddressed.Footnote 58 For the theft of aid, only the IO channel is effective at remedying the citizens’ ire. However, for the other three issues, the optimal use of each channel leads to higher support than when the donor does not address the issue at all.Footnote 59 Except for the case of aid theft, each channel allows the donor to design additional aid that would make people more supportive than if it remained oblivious to the issues.

DISCUSSION AND BROADER IMPLICATIONS

Our findings lay out a more nuanced, complex understanding of voters’ preferences regarding foreign aid than what other recent theories assume. Consistent with these aid allocation theories, we find that voters care about the moral consequences of aid policy. However, and contrary to commonly invoked assumptions, the moral dimension of public opinion does not have a clear and unidirectional effect on preferences over policy. We found no evidence that aid withdrawals mitigate voters’ moral ire about aiding nasty regimes, as is often assumed by recent theories. This is not surprising if we account for people’s additional concerns about material benefits. Because aid cuts would jeopardize flows of benefits from the recipients, voters do not wholeheartedly support weakening ties with the nasty recipients. It stands to reason that a withdrawal of aid is likely not the optimal response for the donor government, and sudden drops in aid flows to these regimes seem unlikely. It follows that parts of the recent theories are unlikely to hold.Footnote 60

We find that voters prefer increased engagement with nasty regimes rather than weakening ties with them. Paradoxically, our findings suggest that voters’ morality-driven support may push the government to give more aid to nasty regimes.Footnote 61 This provides possible reasons why massive amounts of foreign aid continue to be sent to countries like Egypt and Pakistan, and why scholars have been unsuccessful at finding clear evidence in favor of moral considerations in overall aid allocations.Footnote 62

Our findings about addressing also suggest areas in which moral concerns may materialize in the study of actual aid flows. We expect that more specialized, issue-specific aid (and not necessarily general aid) should be given to regimes with objectionable policies in order to maintain engagement. Some existing evidence is consistent with this expectation: Nielsen shows that funds specifically for human rights and democracy promotion increase as a recipient’s respect for human rights declines.Footnote 63 While it is not clear from his empirics how such increases in specialized aid are tied to other categories of aid, our study shows the importance of thinking through the complex mechanisms through which people’s preferences affect policies.

In this spirit, we engage our arguments and results further by discussing what they suggest to the broader aid literature. Below, we discuss in more detail three ideas that we see as ripe for exciting future research.

Aid Heterogeneity and Fragmentation

While we kept our experiment simple by having only one policy that makes the recipient nasty, many of these unpalatable policies occur jointly.Footnote 64 In turn, the donor government would have to address multiple issues simultaneously. This may lead to what is commonly known as ‘aid heterogeneity’, ‘project proliferation’ or ‘aid fragmentation’ – many projects with varying purposes delivered through different channels.Footnote 65 Development scholars often complain that such heterogeneity represents a drain on aid because it spawns extra administrative and reporting responsibilities for recipient governments. Development advocates have moved to rank, name and shame donors for high levels of fragmentation.Footnote 66

The existing literature on aid heterogeneity largely focuses on the effectiveness of different modalities and channels of aid as well as what gives rise to specific types and delivery channels.Footnote 67 Quite sensibly, almost all such research focuses on one or two aspects of aid heterogeneity at a time.Footnote 68 However, one downside of such an approach is that we are left with separate bodies of knowledge that do not inform us about the realizations (or lack thereof) of other dimensions. For example, McLean explains delegation to IOs in the context of environmental aid.Footnote 69 While she provides insights into her research question, her study stays silent on why NGOs would not be a better delivery channel, or why aid is allotted to environmental issues but not health goals.

This exemplifies what Most and Starr call ‘islands of knowledge’, a fragmentation of insights.Footnote 70 Other bodies of international relations literature take to heart this greater scope of study. For example, the study of foreign policy does so under the name ‘foreign policy substitutability’ and the study of international co-operation via the ‘the rational design of institutions’ framework.Footnote 71 We believe the study of foreign aid could also advance further by studying aid heterogeneity more generally under a common theoretical framework. Our evidence points to donor citizens’ aid preferences and the donor government’s addressing strategies as useful starting points.

Does Addressing Aid Work?

Our findings also have implications for aid effectiveness, which remains an active area of research. In particular, they speak to the puzzle of why recipient regimes would allow certain types of aid that appear to weaken the capacity of the regime. Most notably, recent evidence concurs that democracy aid, which funds projects for civil society vibrancy, is effective at inducing democratization and accountability.Footnote 72 Then, why would a (nasty) dictator allow such funding? Arguments by Dietrich, Bush and us point toward an answer to this puzzle.Footnote 73

Our argument suggests that the donor government’s principal, the voters, entangles aid for the policy concession with aid to address deficits in democracy. If people’s moral motives were absent, recipient and donor governments would prefer to collude on pure aid-for-policy dealsFootnote 74 as they would save the donor government money (that is, specialized aid) and the recipient government would not have to deal with regime-threatening ‘intrusions’. This collusion would ensure that the donor gets policy spoils (at some opportunity costs) and the recipient gets funds to bolster the regime.Footnote 75

However, the problem is that the donor public takes umbrage with a nasty recipient regime. When the public can affect its government, the donor is forced to address the unsavory policies to prevent the aid-for-policy deal from unraveling at home. Thus people’s moral motives force governments into a new equilibrium and away from the pure collusion constellation. The donor gives aid to pay for policy concessions as well as aid to address the offensive issue, which the recipient accepts. However, in the case of democracy aid, these additional funds may weaken the government’s hold on autocratic power.Footnote 76

This logic may explain why recipient regimes are willing to accept remedial aid that threatens their survival, as prior research demonstrates. That raises a subsequent question: why would such remedial, addressing aid be effective? After all, nothing in our own theoretical account requires it to actually achieve something; it might as well be a kabuki theater. Effectiveness might come about through a long chain of delegation from people to NGOs and IOs that execute the projects. Bush and Dietrich argue that NGOs try to be effective because their governmental funders monitor them, and in turn report to their voters that their tax money (that is, aid) was not squandered abroad.Footnote 77 NGOs’ incentives are insufficient to ensure effectiveness, since the recipient government may still stonewall or sabotage the projects. However, if the recipient government were to do so, NGOs would portray the recipient as the prime detractor,Footnote 78 which would ultimately fray the addressed aid-for-policy collusion between the donor and the recipient governments. Thus, both NGOs and the recipient government have incentives to make sure that addressing aid works to maintain the aid flows.

Messages about Aid

Much debate about foreign aid and development occurs in public. For example, in 1947, US President Truman was concerned with obtaining public support for what came to be known as the Marshall Plan. He worried that the public would object to his administration providing aid to a corrupt and non-democratic Greek government. Truman reflected in his memoirs that ‘there was considerable discussion on the best method to apprise the American people of the issues involved’, settling eventually on ‘[explaining] aid to Greece not in terms of supporting monarchy but rather as a part of a worldwide program for freedom’.Footnote 79 Today, books on development aid are mainstream,Footnote 80 and celebrity activists such as Bob Geldof and Bono engage the public widely. Implicit in their efforts to manipulate and convince the public is the belief that public support is crucial to make progress on development and that it is possible to shape public opinion on foreign policy. Recent research agrees with the latter that public opinion on foreign policy is malleable via elite messaging.Footnote 81

Our results show that some aspects of a multifaceted foreign aid policy resonate with people, and that some of those are under the donor government’s control. However, the public is often ill informed about foreign policy in general and foreign aid in particular. Therefore, even if actual aid policy reflects citizens’ concerns, they may not be aware that it does, and thus their opinion does not respond to changes in aid policies. An important missing step is that citizens learn about aid policy from the messages sent by elites and the media.Footnote 82 Thus, in addition to choosing appropriate volumes, types, targets and delivery channels of aid, we might expect the donor governments to tailor messages in ways that increase public support and avoid criticism.Footnote 83 In particular, our evidence leads us to expect donor governments to downplay unpalatable policies chosen by the recipient (and turn to providing more aid to address the issue).

Two observations provide preliminary support for the basics of this expectation. First, all aid agencies spend non-trivial resources on public relations,Footnote 84 produce streams of press releases and are active on social media. Secondly, we have some evidence that governments care about messages related to their policies, and seek to manipulate unwanted information. For instance, Dreher, Marchesi and Vreeland report that the International Monetary Funds (IMF) biases its growth and inflation forecasts favorably for states that are friendly to the United States, and Qian and Yanagizawa find that the US State Department tends to downplay human rights violations for military allies.Footnote 85 In each case, presumably indirectly for the IMF and directly for the State Department, the US Government works to prevent issues (low growth, high inflation, bad human rights) from stirring people’s ire, which might jeopardize what we would call policy concessions.

With the proliferation of sources that report on the domestic policies of developing countries, it seems unlikely that such unpalatable policies will consistently remain out of citizens’ sights. As the donor government has difficulty suppressing information that could jeopardize aid-for-policy deals, sending messages about how the government addresses the issue is bound to become more important. To our knowledge, Van der Veen and Heinrich, Kobayashi and Bryant provide the only related academic treatments of donor governments’ messaging in the foreign aid realm.Footnote 86 We view this as an area for more exciting and important research.

CONCLUSION

Recent attempts to understand foreign aid decisions have relied heavily on ideas of domestic politics, mirroring a trend in the broader foreign policy literature.Footnote 87 This body of work has enriched our understanding of the forces behind foreign aid, from legislators’ constituencies to news coverage,Footnote 88 and from international social network connections to attitudes toward for foreign aid.Footnote 89 We focused on the recent work that contrasted valuation for aid to be given in a selective way, to favor well-governed and democratic countries on one side, but also the use of aid for foreign policy purposes. This work rests on a common set of assumptions about voters’ preferences and how donor governments react to these preferences. Unless voters evaluate foreign aid on moral grounds and governments’ response to voters’ concerns by withdrawing aid from recipients, the roots of these theories are not deep. Our evidence supports the basic idea that voters see foreign aid as a policy tool that ought to be used in a moral way. (Direct) concerns about obtaining policy concessions can play only a limited role.

We also studied how donor governments can manage voters’ moral concerns. Surprisingly, our findings suggest that the public’s moral concerns can be effectively mitigated by getting more involved with recipients, which is contrary to what existing work has suspected.Footnote 90 More specifically, voters appreciate when their governments directly tackle the recipients’ issues that they find objectionable. Compared to other remedial actions, such as withdrawing aid or diverting attention, voters’ concerns lessen significantly more when governments promise to provide more aid to address such issues.

Taken together, by optimally administering more aid, the donor government can undo a substantial amount of harm induced by the recipient government’s choices. That is, by providing even more aid to address the underlying, offending issue, the public’s moral malcontent can be significantly mitigated. Doing something in this context is almost always better than doing nothing.