Is foreign aid an effective instrument of soft power? Does it generate affinity for donor countries and the values they espouse? What effect, if any, does it have on perceptions of donors’ geopolitical rivals? Given that aid is one of the most frequently used tools for increasing international influence, these questions remain surprisingly understudied. Donors spend billions of dollars annually in aid to the world's poorest countries. Beyond its commercial and development objectives, aid is branded and promoted with the aim of generating support for the donor country among recipient populations, and transmitting political principles in line with the donor's worldview. Over time, aid may induce recipient populations to become increasingly receptive to the donor's foreign policy goals, to the point that they ‘want what it wants’, as Nye (Reference Nye2004) famously conceived of soft power.

We propose a theory that explains the effects of aid on soft power through a process of exposure, attribution, affect and ideological alignment. Citizens of recipient countries must first be exposed to donor-funded projects – either directly (as beneficiaries) or indirectly (through media or word of mouth) – which they must accurately attribute to the donor that funded them. If recipients believe they benefit from these projects, they may update their priors to become more favorable to the donor country. Beyond this increase in ‘positive affect’ toward donors (Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017, 135–6), aid may also induce a more profound shift in recipients’ perceptions of the models of governance and development that donors promote – liberal democracy, for example, or free market capitalism. Inducing a shift of this sort is central to democracy and civil society programs administered by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the UK's Department for International Development (DIFD) and other donors (Scott Reference Scott2019).

We test our theory in the context of China's rapidly expanding presence in Africa. China is now the region's largest trading partner, and is coming to rival Western donors in the amount of aid it delivers to the continent. China is also actively seeking to strengthen its soft power in Africa (Kurlantzick Reference Kurlantzick2007). The Chinese government supports a wide range of cultural and educational programs abroad, and invests heavily in branding and diplomacy to publicize the aid it provides (Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2019). Over the last decade, Chinese leaders (the president, premier or foreign minister) have made over eighty trips to African countries. These visits often entail the signing of numerous bilateral agreements and commitments to refurbish hospitals, pave roads, build airports and undertake other infrastructure projects, often accompanied by proclamations of solidarity and ‘win–win cooperation’ between China and Africa.Footnote 1

China's expanding aid regimeFootnote 2 competes directly and indirectly with more ‘traditional’ donors, especially the United States. While both China and the United States prioritize economic development, the United States puts greater rhetorical and programmatic emphasis on good governance, democracy and liberal values (such as respect for a free and independent civil society). The United States has also adopted a variety of safeguards with the stated purpose of reducing corruption in the administration of aid. In contrast, China explicitly rejects the West's ‘politicization’ of aid, and instead advances what President Xi Jinping has described as a ‘five-no’ aid regime,Footnote 3 which imposes no good governance conditionalities and thus aims to minimize interference in the politics of recipient states. Chinese leaders view these aspects of the Chinese aid regime as crucial to soft power, which they frame as ‘direct competition in great power terms’ (Yoshihara and Holmes Reference Yoshihara and Holmes2008, 134). The United States in turn perceives Chinese aid as a tool to strengthen Beijing's ‘dominance’ and undermine American influence on the continent.Footnote 4

The small number of studies that have examined aid as an instrument of soft power focus on theorizing about and testing the impact of aid from a single donor on perceptions of that donor (Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017; Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner Reference Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner2018; Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014). We extend these studies by exploring the potentially unique dynamics that arise when geopolitical rivals deliver aid to the same countries at the same time. We theorize that the distinct and competing Chinese and American aid regimes may produce a substitution effect, whereby aid from one donor increases support for that donor and the values it espouses, while diminishing support for the donor's geopolitical rivals. By this logic, we should expect African beneficiaries of Chinese aid to express greater affinity for China and its political and economic model, and less affinity for the American alternative. African citizens exposed to Chinese aid should also express greater support for political principles typically associated with China and other one-party states, such as the virtues of state-led development, single-party rule and a more tightly regulated civil society. Exposure to US aid should have the opposite effect.

We test the observable implications of our theory by combining data from the Afrobarometer survey with information on the locations of US- and Chinese-funded aid projects gleaned from AidData and the Aid Information Management Systems (AIMS) of African finance and planning ministries (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher2016; Strange et al. Reference Strange2017). To correct for potential selection effects arising from the non-random distribution of Chinese and US aid, we use a spatial difference-in-differences estimator with country and Afrobarometer round fixed effects, which allows us to compare the attitudes of citizens living near completed projects to the attitudes of those living near planned (future) projects for which a formal agreement has not yet been reached (Briggs Reference Briggs2019; Isaksson and Kotsadam Reference Isaksson and Kotsadam2018a; Kotsadam et al. Reference Kotsadam2018). Our identifying assumption is that planned and completed projects are subject to similar selection processes, such that citizens who live near planned projects are valid counterfactuals for those living near completed ones. We address potential violations of this assumption below.

We find that aid from geopolitical rivals produces substitution effects, but in complex and sometimes surprising ways. After correcting for potential selection biases, our results suggest that Chinese projects decrease recipients’ affinity for China while increasing their affinity for the United States. US aid appears to weaken support for China while strengthening support for the United States – a more straightforward substitution effect. Our results also suggest that US aid increases support for the liberal democratic values that are more often associated with the United States than with China, such as the belief in the importance of multiparty elections. We then test whether these results extend beyond the United States. After correcting for potential selection effects, Chinese aid appears to improve perceptions not just of the United States, but of France and the UK as well – former colonial powers that, like China, are often accused of pursuing ‘neo-colonial’ ambitions in Africa.

Importantly, we cannot disentangle the impact of Chinese official development assistance (ODA) from that of other forms of Chinese economic engagement (Other Official Flows, or OOF), or from the various financial and commercial activities that tend to accompany Chinese aid (such as an influx of Chinese firms and workers into recipient countries). Chinese ODA and OOF tend to be inextricably intertwined, and it is possible that aid delivered in isolation might have more positive effects on Chinese soft power. Our goal is not to test this proposition, but rather to estimate the impact of Chinese ‘aid’ broadly defined, as it is actually delivered on the ground. Taken together, our results belie the concern often expressed by US government officials and foreign policy commentators that Chinese aid is diminishing American soft power or eroding Africans’ commitment to liberal democracy (Brookes and Shin Reference Brookes and Shin2006, 1–2; Sun Reference Sun2013, 6–7). If anything, the opposite appears to be true.

Our study contributes to five strands of literature. First and most directly, it advances research on aid as a foreign policy tool. With few exceptions (Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017; Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner Reference Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner2018; Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014), this literature has focused on evaluating aid as an instrument of hard power, for example by testing whether aid induces recipient governments to vote with the donor country in the UN General Assembly (Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008). Influencing the actions of recipient governments is important, but so is influencing the attitudes of recipient populations. As Nye (Reference Nye2004, 18) famously argues, public support as expressed through polls and other mechanisms is a crucial indicator of soft power, revealing ‘both how attractive a country appears and the costs that are incurred by unpopular policies’. That (un)attractiveness, in turn, ‘can have an effect on our ability to obtain the outcomes we want in the world’ (Nye Reference Nye2004, 18).

Aid is arguably especially likely to bolster soft power at the micro level, where it may serve as ‘an expression of [the donor country's] values’ among citizens of recipient countries, thus helping to ‘enhance [the donor's] “soft power”’ (Lancaster Reference Lancaster2000, 81). A small number of recent studies have explored this possibility, with mixed results (Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017; Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner Reference Eichenauer, Fuchs and Brückner2018; Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014). We draw on these studies, and extend them in several ways: by theorizing and testing the effects of aid not just on perceptions of the donor, but also on perceptions of the donor's geopolitical rivals, and not just on perceptions, but also on adherence to the political principles that donors seek to inculcate. We also theorize and test the effects of aid from two competing donors with conflicting foreign policy agendas, both of which seek to use aid to influence public opinion in the same countries at the same time. The efficacy of aid as a source of soft power is arguably especially relevant in these settings, where the stakes for donors are especially high.

Secondly, our study contributes to research on the effects of aid on democracy in recipient countries. This literature has typically focused on assessing whether aid promotes democratization cross-nationally (Bermeo Reference Bermeo2016; Brautigam Reference Brautigam1992; Carnegie and Marinov Reference Carnegie and Marinov2017; Finkel, Pérez-Liñán and Seligson Reference Finkel, Pérez-Liñán and Seligson2007; Knack Reference Knack2004; Yuichi Kono and Montinola Reference Yuichi Kono and Montinola2009), but generally has not explored whether aid instills liberal democratic values sub-nationally as well, through its effects on recipient populations. In some cases these values may promote democratization in and of themselves – for example, if they catalyze protest against autocratic regimes.

Thirdly, the study contributes to research on the effects of aid at the micro level more generally. Much of this literature has focused on testing whether aid diminishes citizens’ support for their own governments (Baldwin and Winters Reference Baldwin and Winters2020; Blair and Roessler Reference Blair, Roessler and Marty2021; Brass Reference Brass2016; Dietrich and Winters Reference Dietrich and Winters2015; Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017; Guiteras and Mobarak Reference Guiteras and Mobarak2015; Sacks Reference Sacks2012). Aid's impact on citizens’ support for donor countries is arguably equally important, but remains understudied.

Fourthly, our study contributes to research on China's expanding role as a donor and investor in Africa (Bluhm et al. Reference Bluhm2018; Brautigam Reference Brautigam2009; Brazys, Elkink and Kelly Reference Brazys, Elkink and Kelly2017; Dreher et al. Reference Dreher2018; Isaksson and Kotsadam Reference Isaksson and Kotsadam2018a). Surveys suggest that China's approach to aid has attracted considerable support among African citizens (Lekorwe et al. Reference Lekorwe2016), but these descriptive patterns cannot be used to understand the causal effect of Chinese aid on those affected by it. We help fill this gap.

Finally, our study contributes to a more general literature on rivalries between established and emerging powers, especially between China and the United States in the early twenty-first century (Friedberg Reference Friedberg2005; MacDonald and Parent Reference MacDonald and Parent2018). Competition over soft power is one important arena in which this rivalry manifests. Interestingly, we find that China's ostensibly apolitical approach to aid does not make its aid any less political. On the contrary, we find that Chinese aid appears to shape the perceptions and beliefs of citizens in recipient countries in ways that may be disadvantageous for China, and advantageous for the United States. Combined with recent research showing that Chinese aid exacerbates corruption and undermines collective bargaining in recipient countries (Isaksson and Kotsadam Reference Isaksson and Kotsadam2018a, Reference Isaksson and Kotsadam2018b), our results suggest that the political implications of aid may be unavoidable, even (and perhaps especially) for donors that seek to avoid them.

Theoretical Framework

Foreign Aid and Perceptions of Donors

Does foreign aid improve perceptions of donors among citizens of recipient states? Does it increase support for the values that donors espouse? Most research on aid tests whether it is effective at promoting democracy, improving governance, or alleviating poverty and stimulating economic growth (see Glennie and Sumner Reference Glennie and Sumner2014 for a review). A smaller but important literature tests the effects of aid on citizens’ perceptions of recipient states (Baldwin and Winters Reference Baldwin and Winters2020; Blair and Roessler Reference Blair, Roessler and Marty2021; Brass Reference Brass2016; Dietrich and Winters Reference Dietrich and Winters2015; Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017; Guiteras and Mobarak Reference Guiteras and Mobarak2015; Sacks Reference Sacks2012). Far fewer studies have addressed the impact of aid on perceptions of donor countries. (We discuss a few exceptions below.)

This is surprising. States have long used aid to improve diplomatic relations with recipient governments, increase support for specific policy positions and more generally ‘shift public opinion in a way likely to leave [donors] safer from transnational threats and more able to obtain cooperation from the countries to which they send foreign aid’ (Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017, 133; see also Katzenstein and Keohane Reference Katzenstein and Keohane2007). Maintaining a positive public image abroad is believed to be important for achieving foreign policy objectives (Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014), and changes in domestic perceptions of other countries have been shown to predict changes in foreign policy towards those countries as well (Goldsmith and Horiuchi Reference Goldsmith and Horiuchi2012). Ideological alignment is also widely believed to be a key lever of foreign policy influence, especially in the United States. As Radelet (Reference Radelet2003, 109) observes, ‘the United States needs poor countries to support the values it champions’.

How might aid improve a donor's public image and foreign influence? Aid can serve as a source of either soft power or hard power (or both). The line between hard and soft power is often blurred, especially in the realm of economic influence and inducement, and the differences between them are best conceptualized as a continuum (Watanabe and McConnell Reference Watanabe and McConnell2008).Footnote 5 Hard power entails the use of coercion and material inducements to compel states and their citizens to adopt policy positions they might not otherwise accept. Foreign aid can serve as such an inducement, especially at the macro level, for example when it is used to influence the way member states vote in the UN (Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele Reference Dreher, Nunnenkamp and Thiele2008). Transactional effects are less likely to be relevant at the micro level, unless citizens strategically express or withhold their support for donors in the hope of influencing the amount of aid those donors provide. Exerting influence of this sort is likely beyond the capacity of most beneficiaries, even when they act collectively. At the micro level, soft power is likely to be more salient than hard power.

In contrast to coercive or transactional sources of influence, soft power generates support and alignment through ‘attraction’ and getting others to ‘want what [the donor country] wants’ (Nye Reference Nye2004). Aid can elicit attraction by creating the impression that donor countries and their citizens are virtuous, generous and compassionate. Foreign donors strive to brand their aid in this way. For example, USAID brands its aid as ‘from the American people’ to evoke the generosity and goodwill of American citizens; DFID brands its aid as ‘from the British people’ for similar reasons. If beneficiaries internalize this perception, they may develop greater affinity for donor countries, their citizens and their foreign policies. Aid may also increase donor countries’ ‘appeal’ through the transmission of political values, which Nye (Reference Nye2004) cites as one of the core bases of soft power. Beneficiaries who admire the principles that they believe guide a donor country's foreign policy may be more likely to align with that donor than with its rivals.

While global powers disseminate their political principles and ideals in many ways, aid is arguably one of the most important. For many beneficiaries, aid-funded projects are the most salient expressions of the donor country's foreign policy and political values (Lancaster Reference Lancaster2000). As Carothers (Reference Carothers2011, 341) notes, aid projects that implicitly or explicitly advance political values, such as democracy assistance, do not just affect the institutions and organizations to which they are directed; they also influence individuals ‘through the transmission of ideas that will change people's behavior’. We expect this process of ideological alignment – in which beneficiaries come to adopt the political values of a particular donor – to represent a more enduring source of soft power.

Ideological alignment may have important implications not just for the foreign policies of donor countries, but for the domestic politics of recipient countries as well. For example, beneficiaries who adopt the liberal democratic values espoused by donors like the United States or the UK may be more likely to apply pressure on their own governments to liberalize and democratize. Some of the most canonical theories of democratization and democratic consolidation in political science hinge crucially on citizens’ demand for democracy (Almond and Verba Reference Almond and Verba1963; Easton Reference Easton1965; Lipset Reference Lipset1959), and more recent empirical studies have documented a positive relationship between public opinion about democracy and the quality of democracy itself (Claassen Reference Claassen2020). The fact that citizens demand democracy does not imply that governments will supply it, and in many African countries, ‘the people's desire for democracy is not matched by elite commitment to it’ (Yarwood Reference Yarwood2016, 52). Nonetheless, without some degree of popular pressure, it seems likely that the quality of democracy in Africa would deteriorate further.

Of course, it is possible that donors express support for liberal democratic (or other) values while providing material or other forms of assistance to autocratic governments, or otherwise advancing authoritarian causes. Hypocrisy of this kind is nothing new in foreign policy, and donors like the US and the UK have a long history of supporting autocratic regimes in Africa both during and after the colonial era. If citizens are sensitive to these discrepancies between stated principles and observed actions, then we should expect to find that aid has no (or perhaps even negative) effects on beneficiaries’ political beliefs. This is an empirical question to which we have few empirical answers.

The limited evidence on the efficacy of aid as a source of soft power is mixed. Cross-nationally, Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood (Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014) find that increases in funding for the US President's Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief are correlated with improvements in attitudes towards the United States. In Bangladesh, Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters (Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017) find that while most citizens do not accurately attribute USAID-sponsored projects to the United States, once they are informed about the source of funding for these projects, their perceptions of the United States improve, albeit only modestly. Conversely, Böhnke and Zürcher (Reference Böhnke and Zürcher2013) find that aid to Afghanistan has not improved Afghans’ perceptions of donors. And in India, Dietrich and Winters (Reference Dietrich and Winters2015) find that information about the provenance of a US-funded HIV/AIDS program does not alter perceptions of the United States one way or the other.

The efficacy of aid as a source of soft power becomes especially relevant when multiple donors with conflicting foreign policy agendas seek to use it to win hearts and minds in the same countries at the same time. Aid does not occur in a geopolitical vacuum, and the effects of assistance given by one donor may be offset by the countervailing effects of assistance delivered by another. During the Cold War, for example, US President John F. Kennedy's ‘Alliance for Progress’ program in Latin America was designed not just to promote economic development and political reform, but also to prevent the spread of communism in the wake of the Cuban Revolution (Taffet Reference Taffet2007). Other aspects of the US government's Cold War-era aid regime were similarly motivated by competition with the Soviet Union. The Soviets responded in kind, providing enough assistance to roughly equal the United States' expenditures as a share of GNP, and using aid as a tool to project power, attract allies and persuade recipient populations of the virtues of the Soviet model relative to its US counterpart (Roeder Reference Roeder1985). Few previous studies have addressed the possibility of these offsetting effects in a systematic way.Footnote 6

The Debate about China

Debates about the impact of aid on beneficiaries’ attitudes have become especially salient with China's rise as a prominent purveyor of assistance to the world's poorest countries, especially in Africa. China has considered aid to be a ‘useful policy instrument’ since the early days of the People's Republic (Sun Reference Sun2014). But the scope and ambitiousness of Chinese aid has increased dramatically in recent years. Between 2000 and 2012, China committed some $52 billion in aid to Africa alone (Bluhm et al. Reference Bluhm2018). China is also Africa's largest creditor, having extended more than $86 billion in commercial loans to African governments between 2000 and 2014 (Brautigam and Hwang Reference Brautigam and Hwang2016).

In line with a broader push to strengthen its soft power around the world (Kurlantzick Reference Kurlantzick2007), one of China's primary goals as a donor and lender is to generate public support abroad and bolster its international influence (Hanauer and Morris Reference Hanauer and Morris2014a). Shortly after becoming president, Xi Jinping emphasized the importance of greater investment in soft power to strengthen China's influence globally, stating at the fourth Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs that ‘we should increase China's soft power, give a good Chinese narrative, and better communicate China's message to the world’ (Brazys and Dukalskis Reference Brazys and Dukalskis2019, 1). In Africa especially, China has launched a ‘robust continent-wide public diplomacy campaign to improve its image’ (Hanauer and Morris Reference Hanauer and Morris2014b, 71). Soft power has been described as the ‘most potent weapon in Beijing's foreign policy arsenal’ (Kurlantzick Reference Kurlantzick2007, 5).

Importantly, Chinese leaders tend to frame aid and other mechanisms of soft power in terms of competition and great power politics (Yoshihara and Holmes Reference Yoshihara and Holmes2008). During the Cold War, Chinese Premier Zhou Enlai visited ten African countries to announce his ‘Eight Principles of Foreign Economic and Technological Assistance’, developed to help China compete with the United States and the Soviet Union for Africans’ ‘approval and support’ (Sun Reference Sun2014). These efforts further expanded during the Cultural Revolution, and China's approach to aid and investment now constitutes an alternative model that appeals to many Africans and African heads of state, especially in its rejection of the good governance conditionalities favored by many OECD-DAC donors,Footnote 7 including the US and the UK.Footnote 8

China also tends to favor models of state-led development that have proven especially attractive in Africa's authoritarian and electoral authoritarian regimes, such as Ethiopia, Rwanda and Uganda. China explicitly contrasts its approach to aid and economic development with that taken by OECD-DAC donors, especially the United States (Hanauer and Morris Reference Hanauer and Morris2014b, 10). Some US analysts view these developments as a threat to American influence in Africa (Brookes and Shin Reference Brookes and Shin2006; Sun Reference Sun2013); Nye (Reference Nye2005) himself has warned that ‘the rise of China's soft power – at America's expense – is an issue that needs to be urgently addressed’. Others are more sanguine (Hanauer and Morris Reference Hanauer and Morris2014a). Meanwhile, the ‘Chinese model’ of aid continues to attract adherents in Africa (Lekorwe et al. Reference Lekorwe2016). More generally, as Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood (Reference Goldsmith, Horiuchi and Wood2014, 88) note, ‘competition between major powers such as [the United States] and China for favorable perceptions in global public opinion is increasingly evident today and likely to be a pivotal feature of the emerging international order’.

Hypotheses

We test the effects of foreign aid on citizens’ perceptions of competing donors and the values they espouse, focusing on the rivalry between China and the United States in Africa. If aid not only boosts the influence of donors but also diminishes the influence of its rivals, then we should expect Chinese aid to (1) increase support for China and its role in African countries, while (2) decreasing support for the United States and the role it plays. If aid also induces alignment with political principles associated with the donor, then we should further expect Chinese aid to (3) decrease commitment to liberal democratic values among citizens of recipient states. The inverse should be true for US aid.

These hypotheses are all grounded in the idea that aid can shape recipient populations’ attitudes and values. While policy makers regularly advance this idea, there are reasons for skepticism. For aid to improve citizens’ perceptions of donors, citizens must accurately attribute donor-funded projects to the donor that funded them, and must experience some feeling of gratitude, indebtedness or ‘diffuse positive affect’ towards the donor as a result (Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017, 135–6). For aid to diminish support for the donor's rivals, citizens must accurately perceive donors as rivals in the first place, and the gratitude or indebtedness they feel towards one donor must be matched by disaffection towards the other. Finally, for aid to induce alignment with the donor's political principles, citizens must accurately associate the donor with those principles, and must conclude on the basis of exposure to donor-funded projects that those principles are sound.

The plausibility of this causal chain is an open empirical question. The first link has received the most attention from scholars, but the findings are mixed. In a survey experiment in Bangladesh, Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters (Reference Dietrich, Mahmud and Winters2017) find that most respondents did not accurately attribute a USAID-branded health clinic to the United States. In another survey experiment in Uganda, Baldwin and Winters (Reference Baldwin and Winters2020) similarly find that most respondents did not know the provenance of a ‘grassroots human security project’ funded by Japan and implemented by local non-governmental organizations. By contrast, Dolan (Reference Dolan2020) finds that interview respondents in Kenya generally have a sophisticated and remarkably accurate understanding of the role that aid plays in financing public goods. In Appendix E, we use original survey data from an unrelated study in Liberia (Blair and Roessler Reference Blair and Roessler2021) to show that respondents who live near Chinese-funded projects are more likely to report knowing about and using Chinese-provided services than those who live further away, and are more likely to report working for a Chinese-funded contractor.

Other links in the causal chain have received less attention; all are plausible, but none is certain. African leaders often characterize China and the United States as competing providers of foreign aid, and those who favor China often frame their preference in terms of dissatisfaction with Western alternatives (and vice versa) (for example, Wade Reference Wade2008). It is possible that African citizens draw similar distinctions. Given the prominence of both the United States and China on the world stage, it is also possible that African citizens are aware of the ideological differences between them. According to a 2017 Pew Research Center survey covering thirty-eight countries,Footnote 9 31 per cent of respondents believe China respects the personal freedoms of its citizens, compared to 55 per cent who believe it does not. In contrast, 58 per cent of respondents believe the United States respects the personal freedoms of its citizens, compared to 32 per cent who believe it does not. The discrepancy is less stark among respondents from the six African countries in the Pew sample – Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa and Tanzania – but points in the same direction: 61 per cent believe the United States respects personal freedoms, compared to 56 per cent who believe the same about China.

There are also reasons to believe that Chinese aid may actually diminish citizens’ perceptions of China, or at best have no effect on them. While China is often praised for investing in the sorts of large-scale, high-risk infrastructure projects that more ‘traditional’ donors typically avoid, it is also frequently criticized for poor workmanship, exclusionary hiring policies and abusive management practices (Hanauer and Morris Reference Hanauer and Morris2014b). While residents of recipient countries may appreciate China's focus on infrastructure, the (alleged) low quality of Chinese-funded projects combined with the (also alleged) inequitable hiring and management practices of Chinese contractors may produce anger and resentment rather than gratitude and indebtedness. This may decrease beneficiaries’ support for China and its role in their country. Whether there is merit to the allegations about quality and fair play remains a matter of debate, but for the purposes of bolstering (or eroding) soft power, the perception is arguably more important than the reality.

Moreover, China typically frames its aid as value neutral and thus avoids attaching particular principles to the projects it funds. Indeed, this is the core of China's ‘five-no’ doctrine. Despite intense interest in the concept of soft power among Chinese intellectuals and government officials, until recently China's efforts to enhance its soft power lacked sufficient mechanisms to ‘promote Chinese socialist values as an alternative to Western values’ or ‘assertively promote the Chinese development model’ (McGiffert Reference McGiffert2009, 10). The United States is much more aggressive in its use of aid as a vehicle for exporting liberal democracy,Footnote 10 and an increasing fraction of US-funded projects have been devoted specifically to this purpose in recent years (Scott and Carter Reference Scott and Carter2019). Yet while there is some evidence that US democracy promotion efforts have increased recipient governments’ ‘political affinity’ for the United States (Scott Reference Scott2019), to our knowledge no previous study has tested the effects of US (or other) aid on the values of beneficiaries. We treat these as empirical propositions in need of empirical testing.

Research Design

We combine data on Chinese and US aid from AidData and the Aid Information Management Systems (AIMS) of African finance and planning ministries with Afrobarometer data capturing perceptions of China and the United States across thirty-eight African countries.Footnote 11 Surveys are by far the most widely used tool for operationalizing soft power (Holyk Reference Holyk2011) – one recommended by Nye (Reference Nye2004, 6) – though they are of course not the only option (see Blanchard and Lu Reference Blanchard and Lu2012 for examples of alternatives). Round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey includes questions about Africans’ perceptions of the extent and nature of Chinese and American influence in their countries, both in absolute terms and relative to one another. Rounds 2 through 6 also include questions gauging support for liberal democratic values.

To operationalize exposure to Chinese aid, we code whether each Afrobarometer respondent lives within 30 km of a Chinese-funded project. This is the narrowest bandwidth possible given the competing constraints of statistical power and imprecision in the location and timing of Chinese projects in AidData. To address the possibility of a modifiable areal unit problem, in Appendix K we show that our results do not change dramatically or discontinuously when we widen or narrow this bandwidth. We only include projects for which there is precise geographic information within 25 km of a known location (AidData precision code 1 or 2). We also exclude country-wide projects and projects distributed through the central government that only target the capital city. To operationalize exposure to US aid, we use AIMS data from the six African countries for which such data are available, and which were also surveyed by Afrobarometer: Burundi, Malawi, Nigeria, Senegal, Sierra Leone and Uganda.Footnote 12 As with our analysis of Chinese aid, we exclude projects that lack precise geolocation data.

Since AidData covers many more countries than AIMS, wherever possible we run our analysis in two ways: first for Chinese and US aid together in the subset of six African countries for which AIMS, AidData and Afrobarometer data are all available, then for Chinese aid alone in the full set of thirty-eight African countries for which AidData and Afrobarometer data are both available.Footnote 13 We describe our coding rules in further detail in Appendix B, and describe our procedure for coping with missing data in Appendix C. In Appendix C we also show that the projects in our sample do not appear to differ systematically from those in the rest of the AidData or AIMS datasets. As an extension, we code whether each Afrobarometer respondent lives within 30 km of a UK-funded aid project, again using AIMS data from the same six African countries. We provide descriptive statistics and a map of the locations of aid projects and Afrobarometer survey sites in Appendix A.

Aid is not distributed randomly either within or across African countries. To mitigate selection bias, we use a spatial difference-in-differences estimator. Spatial difference-in-differences has been used in several recent studies of aid (Briggs Reference Briggs2019; Isaksson and Kotsadam Reference Isaksson and Kotsadam2018a; Kotsadam et al. Reference Kotsadam2018). In essence, we make three comparisons. First, we compare respondents who live near the site of a completed project to those who do not live near any project, completed or planned. This estimand combines the effect of project completion with any selection bias arising from the non-random distribution of aid. Secondly, we compare respondents who live near the site of a planned (future) project – one for which no formal agreement has yet been reached – to those who do not live near any project, completed or planned. This estimand captures the selection bias. Finally, we subtract this second estimand from the first. Our identifying assumption is that the location of planned projects is a function of more or less the same selection process that determines the location of completed ones. If this assumption holds, then respondents living near planned projects are valid counterfactuals for those living near completed ones, and we can estimate the marginal effect of project completion net of any selection bias by taking the difference between the two regression coefficients.

There are several potential threats to this identifying assumption. One is that recipient governments prioritize projects sited in politically important areas. If projects located in these areas are more likely to be completed than those sited elsewhere, our results may be biased. We view this threat as relatively minor, as we see no reason to expect recipient governments to prioritize in this way during the implementation phase but not the planning phase. (In other words, if recipient governments channel aid to politically important regions, evidence of that selection process should manifest well before implementation begins.) Nonetheless, we control for whether or not each project is located in the region of the president's birth, which has been shown to be an important source of favoritism in the distribution of Chinese aid to Africa (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher2016).

A second potential threat is that donors or recipient governments complete the highest-priority projects first. If planned projects tend to be lower priority than completed ones, then our results may be biased. We address this possibility in Appendix D by exploring whether projects in particular sectors (for example, energy, communications, etc.) are more likely to be completed than those in other sectors (for example, education, sanitation, etc.). If donors complete the highest-priority projects first, then intuitively we should expect certain sectors (such as health) to constitute a larger fraction of completed projects than planned ones. We show that this is not the case. We also include a vector of controls to mitigate any remaining bias, including gender, age, religion, distance to the capital city, a dummy for cities and, as discussed above, a dummy indicating whether the respondent lives in the president's home region.Footnote 14

A third potential threat is that citizens protest projects during the planning phase, causing either the donor or the recipient government to cancel them altogether. Protests, in this sense, are not only an outcome of project planning, but also a potentially confounding determinant of project completion. Again, we view this threat as relatively minor, since there seem to be few (if any) examples of Chinese projects being cancelled due to protests in Africa before 2014 (the last year of the AidData panel),Footnote 15 and no examples of US projects being cancelled for this reason that we are aware of. Nonetheless, as an imperfect proxy, we use the Armed Conflict Location and Event Dataset to control for the number of protests that occurred within 30 km of each respondent before the first project was planned within that same radius. We interpret past protests as a proxy for potential future protests.Footnote 16 In Appendix I we also show that our results are substantively similar when we include only planned projects that we know for certain were eventually completed.

A final potential threat is that planned projects affect beneficiaries’ attitudes towards donor countries even before implementation begins, through something akin to an anticipation effect. While this would not diminish the internal validity of our research design, it would change the interpretation of our spatial difference-in-differences estimates.Footnote 17 We view this threat as relatively minor as well. Recent studies have shown that citizens who live near completed projects tend to be more knowledgeable of those projects, while those who live near planned projects tend to be no more or less knowledgeable than those who live further away (Blair and Roessler Reference Blair and Roessler2021). This suggests that mere project planning is unlikely to generate anticipation effects. Nonetheless, to avoid ambiguities in interpretation, we code planned projects as those for which not even a formal agreement has yet been reached. As these projects had not yet been announced or even formally agreed to at the time respondents were surveyed, we expect no anticipation effects.

Formally, when testing the relationship between Chinese and US aid and dependent variables for which we have multiple rounds of Afrobarometer data, we fit an ordinary least squares (OLS) regressionFootnote 18 given by:

$$y_{ickr} = \alpha + \beta _1c_{ickr}^c + \beta _2c_{ickr}^p + \delta _1u_{ickr}^c + \delta _2u_{ickr}^p + \sum\limits_{\,j = 1}^J {\beta _j} {\rm X}_{ickr} + \lambda _k + \theta _r + {\varepsilon }_{ickr}$$

$$y_{ickr} = \alpha + \beta _1c_{ickr}^c + \beta _2c_{ickr}^p + \delta _1u_{ickr}^c + \delta _2u_{ickr}^p + \sum\limits_{\,j = 1}^J {\beta _j} {\rm X}_{ickr} + \lambda _k + \theta _r + {\varepsilon }_{ickr}$$where y ickr denotes the dependent variable for respondent i in community c in country k surveyed in Afrobarometer round r; ![]() $c_{ickr}^c $ and

$c_{ickr}^c $ and ![]() $u_{ickr}^c $ are dummies indicating whether the respondent lives near any completed Chinese or US projects, respectively;

$u_{ickr}^c $ are dummies indicating whether the respondent lives near any completed Chinese or US projects, respectively; ![]() $c_{ickr}^p $ and

$c_{ickr}^p $ and ![]() $u_{ickr}^p $ are dummies indicating whether the respondent lives near any planned Chinese or US projects, respectively; Xickr denotes J individual-level covariates, described above; λ k and θ r denote country and round fixed effects, respectively; and ɛ ickr is an individual-level error term, clustered by community. The two quantities of interest are β 1 − β 2 and δ 1 − δ 2. For dependent variables for which we have just one round of Afrobarometer data, we omit the round fixed effects.

$u_{ickr}^p $ are dummies indicating whether the respondent lives near any planned Chinese or US projects, respectively; Xickr denotes J individual-level covariates, described above; λ k and θ r denote country and round fixed effects, respectively; and ɛ ickr is an individual-level error term, clustered by community. The two quantities of interest are β 1 − β 2 and δ 1 − δ 2. For dependent variables for which we have just one round of Afrobarometer data, we omit the round fixed effects.

Limitations

Our analysis has at least three limitations. The first is that we only have data on US aid for six African countries. We attempt to address this limitation by running our analyses both with and without US aid whenever possible. The latter analyses allow us to utilize AidData data from all thirty-eight Afrobarometer countries. Secondly, AidData ends in 2014, 1–2 years before round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey was conducted. To address this limitation, we simply exclude round 6 from our analysis whenever possible. For questions that are only available in round 6 – for example, questions about perceptions of China and the United States – we infer the status of projects that were still in the planning phase as of the last year in the AidData dataset, following the coding rules described in Appendix B. We demonstrate the robustness of our results to alternate coding rules in Appendix F. In Appendix G we also show that our results are substantively similar when we use measures of affinity for China and the United States gleaned from round 4 of the Afrobarometer survey. Round 4 was completed in 2008, obviating the need to infer project status in the later years of the AidData panel.

A third limitation is our inability to distinguish Chinese ODA from other forms of Chinese economic engagement (OOF). The former is intended to promote economic or social development; the latter includes loans and credits, and is not necessarily intended to improve economic or social welfare. Unfortunately, the structure and intent of Chinese financial flows is often unclear, such that distinctions can only be drawn suggestively (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher2018). Some of this ambiguity is unavoidable, even intentional: as Sun (Reference Sun2014) notes, ‘China's own policy actively contributes to the confusion between development finance and aid. The Chinese government encourages its agencies and commercial entities to “closely mix and combine foreign aid, direct investment, service contracts, labor cooperation, foreign trade and export”’. Moreover, because the line between state-owned and private enterprises in China is often blurred, ‘Chinese aid and investment are often indistinguishable’ (McGiffert Reference McGiffert2009, 3).

Different types of assistance may reflect different policy priorities, and ideally we could capture these distinctions in our analysis. But while our inability to distinguish ODA from OOF is a limitation, it is not as restrictive as it may seem. Since we are interested in China's impact on perceptions of donor countries, the relevant question for our purposes is how different categories of assistance are interpreted by citizens of recipient states. It seems unlikely that citizens distinguish ODA from OOF, especially in the context of specific projects sited near their homes. While disaggregating ODA from OOF is worthwhile, our inability to do so should not affect the internal validity of our research design, and we interpret our results as capturing the impact of ‘aid’, broadly defined. As a robustness check, in Appendix O we compare the impact of Chinese-funded infrastructure projects to the impact of projects in other sectors.

Results

Effects of Chinese and US Aid on Perceptions of China and the United States

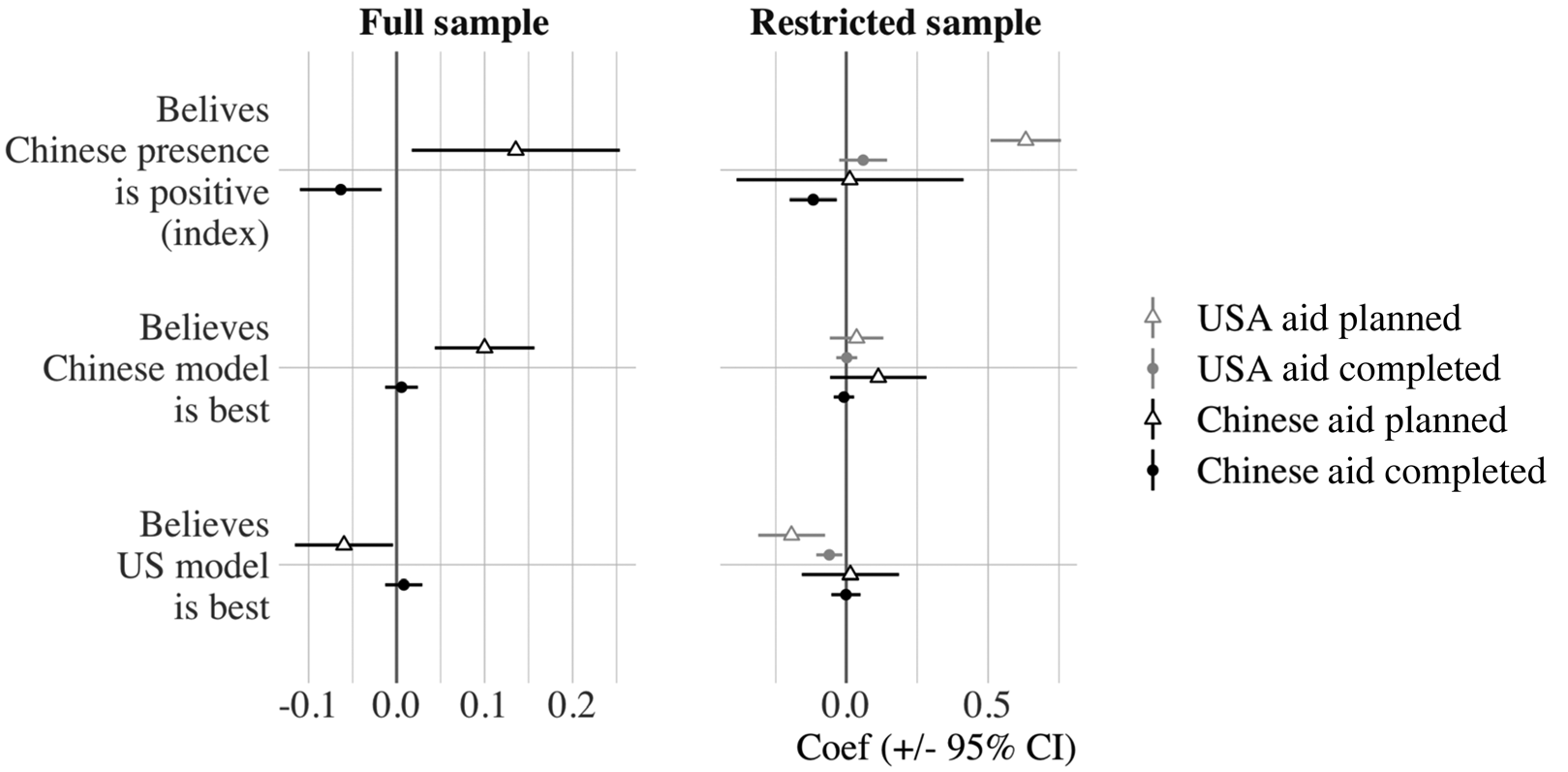

Does aid affect perceptions of donors among citizens of recipient states? Figure 1 reports the effects of proximity to Chinese and US projects on perceptions of China and the United States as measured in round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey. We operationalize perceptions of China using an additive index (ranging from 0–3) that captures the extent to which respondents view China's influence in their country as positive.Footnote 19 Unfortunately, the Afrobarometer survey does not include these exact questions about the United States. To address this limitation, we also test the effects of Chinese and US aid on dummies indicating whether respondents believe the Chinese or American model of political and economic development is best for their country.

Figure 1. Effects of Chinese and US aid on perceptions of China and the United States

Notes: coefficients and 95 per cent confidence intervals from OLS regressions using data from round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey. The left panel displays results for the thirty-eight countries for which Afrobarometer data are available. The right panel displays results for the six countries for which Afrobarometer and AIMS data are available. All specifications include country fixed effects and controls for gender, age, religion, distance to the capital city, number of protests that occurred within 30 km before the first project was planned, a dummy for cities and a dummy indicating whether the respondent lives in the president's home region. Standard errors are clustered by community.

All specifications include country fixed effects, as well as controls for gender, age, religion, distance to the capital city, number of protests that occurred within 30 km before the first project was planned, a dummy for cities and a dummy indicating whether the respondent lives in the president's home region. We present our results graphically for ease of interpretation. The right panel in Figure 1 reports results including both Chinese and US aid for the six countries for which both AidData and AIMS data are available; the left panel reports the results including Chinese aid alone for the thirty-eight countries for which AidData data are available but AIMS data are not. In both panels we are interested in the difference between the coefficient on planned projects and the coefficient on completed ones. Standard errors are clustered by community throughout. For completeness, we also provide results in table form in Appendix P.

The right panel of Figure 1 illustrates that, after differencing away the selection effect, US aid appears to diminish respondents’ perceptions of China, while improving their perceptions of the US model of development. Respondents living near completed US projects score 0.57 points lower on our index of perceptions of China than those living near planned US projects (p < 0.001) – a substantively large reduction of roughly 35 per cent relative to the mean in the sample (1.64), and of roughly 24 per cent relative to the mean among respondents living near planned US projects (2.43). Respondents living near completed US projects are also 13 percentage points more likely to describe the US model of political and economic development as best (p < 0.05) – an increase of roughly 36 per cent relative to the sample mean (0.37), and of roughly 71 per cent relative to the mean among respondents living near planned US projects (0.19).

Chinese aid does not appear to affect perceptions of China in the restricted sample of six countries. When we expand to the full sample of thirty-eight countries in the left panel of Figure 1, however, the effects of Chinese projects are more pronounced, and more negative. After differencing away the selection effect, Chinese projects appear to diminish perceptions of China, weaken the belief that the Chinese model of development is best and strengthen the belief that the American model is best. Respondents living near completed Chinese projects score 0.2 points lower on our index of perceptions of China (p < 0.01) – a reduction of roughly 12 per cent relative to the sample mean (1.67), and of roughly 11 per cent relative to the mean among respondents living near planned Chinese projects (1.86).

Respondents living near completed Chinese projects are also 9 percentage points less likely to describe the Chinese model as best (p < 0.01) and 7 percentage points more likely to describe the US model as best (p < 0.05). These are substantively significant differences of roughly 39 per cent and 23 per cent relative to their respective sample means (0.24 and 0.30), and of roughly 30 per cent and 21 per cent relative to the means among respondents living near planned Chinese projects (0.32 and 0.32). Again, we cannot disentangle the impact of Chinese ODA from that of Chinese OOF, and it is possible that Chinese aid would have more positive effects in isolation. Nonetheless, to the extent that Chinese projects as they are actually implemented affect Africans’ perceptions of donors, our results suggest that the effects are negative.

Our analysis in Figure 1 relies on round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey, which was conducted in 2014 and 2015. As we discuss above and in Appendix B, this requires inferring the future status of projects that were still in the planning phase as of 2014, the last year of the AidData panel. We test the robustness of our results to alternate coding rules in Appendix F. In Appendix G we also test the effects of Chinese aid on perceptions of China and the United States using questions from Afrobarometer round 4, which was conducted in 2008. (Unfortunately, we cannot include US projects in this analysis, as the AIMS dataset only begins in 2008.) Round 4 respondents were asked how much they believe different countries do to help their own country. While these questions are more generic than the ones asked in round 6, they allow us to estimate the effects of Chinese aid without inferring the future status of any planned projects. Our results are substantively similar to those in Figure 1.

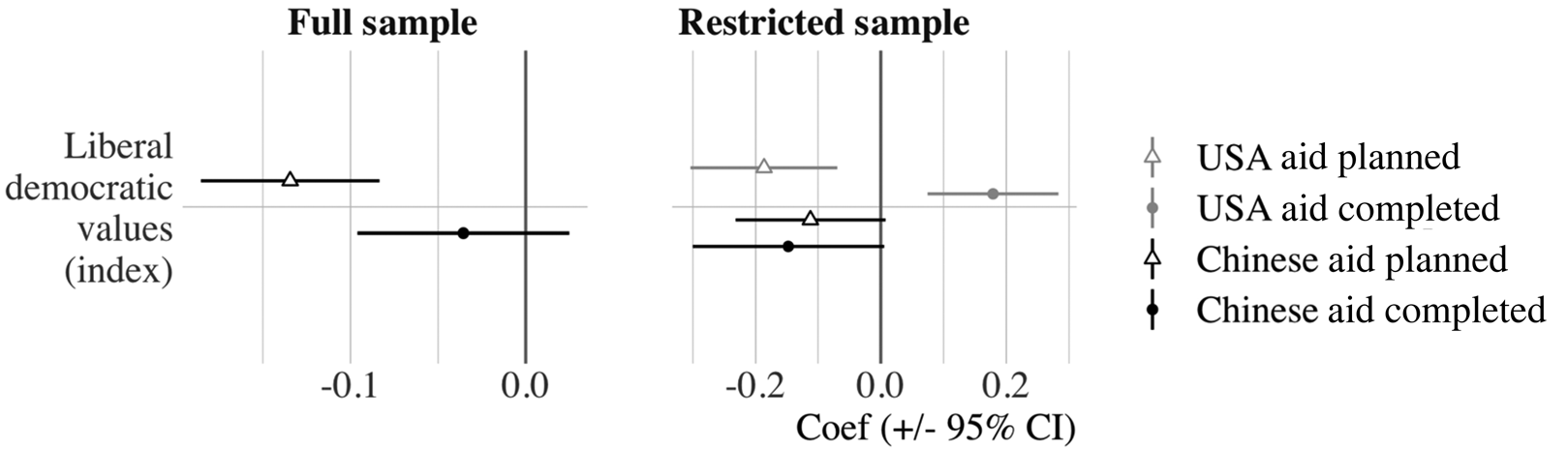

Effects of Chinese and US Aid on Liberal Democratic Values

Does aid increase affinity for the values that donors espouse? Figure 2 tests the effects of Chinese- and US-funded projects on an index of liberal democratic values (ranging from 0–5) that are more typically associated with the United States and other liberal democracies than with China and other authoritarian regimes.Footnote 20 Our index aggregates respondents’ dichotomized answers to questions about the desirability of competition between multiple political parties, a free and open civil society, democracy in general and ‘regular, open, and honest’ elections. We interpret more positive values on this index as indicative of greater alignment with political principles more strongly associated with the United States. More negative values indicate greater alignment with political principles more strongly associated with China. In Appendix H we test the effects of Chinese and US aid on the five components of the index individually.

Figure 2. Effects of Chinese and US aid on liberal democratic values

Notes: coefficients and 95 per cent confidence intervals from OLS regressions using data from rounds 2–5 of the Afrobarometer survey. The left panel displays results for the thirty-eight countries for which Afrobarometer data are available. The right panel displays results for the six countries for which Afrobarometer and AIMS data are available. All specifications include country and Afrobarometer round fixed effects and controls for gender, age, religion, distance to the capital city, number of protests that occurred within 30 km before the first project was planned, a dummy for cities and a dummy indicating whether the respondent lives in the president's home region. Standard errors are clustered by community.

Questions about liberal democratic values are available beginning in round 2 of the Afrobarometer survey, which allows us to avoid the ambiguity involved in using round 6 data alone. The right panel of Figure 2 reports the effects of Chinese and US projects on our liberal democratic values index, focusing on the six African countries for which AidData, AIMS and Afrobarometer data are all available. The left panel of Figure 2 reports the effects of Chinese projects alone, expanding to the thirty-eight African countries for which AidData and Afrobarometer data are available, but AIMS data are not. Since these analyses use multiple rounds of Afrobarometer data, we also include round fixed effects to eliminate confounding due to shared temporal shocks.

The right panel of Figure 2 illustrates that after differencing away the selection effect, US projects appear to strengthen a commitment to liberal democratic values among recipient populations. Respondents living near completed US projects score 0.37 points higher on our index of liberal democratic values than those living near planned US projects (p < 0.001) – an increase of approximately 10 per cent relative to both the mean in the sample (3.72) and the mean among respondents living near planned US projects (3.76). As we show in Appendix H, while this effect is consistent across all five of our proxies for liberal democratic values, it is especially pronounced for the belief that elections are good and that democracy is the best system.

Our results for Chinese aid are more mixed. From the right panel of Figure 2, among the six African countries for which AIMS data are available, Chinese aid has a net null effect on liberal democratic values. However, when we expand our sample to encompass the thirty-eight African countries for which AidData data are available but AIMS data are not, we find that if anything, Chinese aid appears to increase support for liberal democratic values as well, though the effect is substantively small. Respondents living near completed Chinese projects score 0.1 points higher on our liberal democratic values index – an increase of approximately 3 per cent relative to both the sample mean (3.74) and the mean among respondents living near planned Chinese projects (3.63). As we show in Appendix H, this result is driven in particular by a belief in the value of having multiple political parties. This is consistent with our finding in Figure 1 that Chinese aid either increases or has no effect on recipients’ affinity for the United States, and suggests that Chinese aid either increases or has no effect on recipients’ commitment to the values that the United States espouses as well.

Effects of Chinese and US Aid on Perceptions of Former Colonial Powers

Are these results specific to perceptions of China and the United States? If the soft power benefits of China's presence in Africa accrue at least in part to the United States, it is possible that they accrue to other Western countries as well. Afrobarometer data allow us to explore this possibility, albeit indirectly. Round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey asks respondents which country offers the best model of development for their own. The menu of options includes the former colonial power, which in almost all cases is either France or the UK. The French and British aid regimes are similar to those of other OECD countries, and France and the UK are similar to the United States in their efforts to promote liberal democratic values through the provision of aid.Footnote 21

Of course, former colonial powers are not representative of Western countries more generally. But testing the effects of aid on perceptions of former colonial powers is instructive nonetheless. Former colonizers have been shown to favor their former colonies in the distribution of aid, irrespective of need (Alesina and Dollar Reference Alesina and Dollar2000). Through aid and other mechanisms, including language, currency (for example, the CFA franc) and membership in international organizations (such as the British Commonwealth), former colonial powers foster relationships with African countries that are often characterized as ‘neo-colonial’ (see, for example, Taylor Reference Taylor2019). China, too, is widely believed to harbor neo-colonial ambitions in Africa (Rich and Recker Reference Rich and Recker2013). The substitution effects that we observe in Figures 1 and 2 may be less likely to materialize when citizens of recipient countries are asked to evaluate models of development that – while more liberal and democratic than China's – are nonetheless associated with an oppressive colonial past.

Figure 3 reports the effects of Chinese and US aid on Africans’ perceptions of former colonial powers using the same specifications as in Figure 1. Again, the right panel reports the results for both Chinese and US aid across six African countries, while the left panel reports the results for Chinese aid alone across thirty-eight African countries. In both panels, after differencing away the selection effect, we find that Chinese aid appears to improve perceptions of the former colonial power. These effects are substantively very large. From the right panel, respondents living near completed Chinese projects are 9 percentage points more likely to believe the former colonial power's model is best (p < 0.001) – an increase of roughly 91 per cent relative to the sample mean (0.1), and of roughly 594 per cent relative to the (very low) mean among respondents living near planned Chinese projects (0.02). US aid does not appear to affect perceptions of the former colonial power.

Figure 3. Effects of Chinese and US aid on perceptions of former colonial powers

Notes: coefficients and 95 per cent confidence intervals from OLS regressions using data from round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey. The left panel displays results for the thirty-eight countries for which Afrobarometer data are available. The right panel displays results for the six countries for which Afrobarometer and AIMS data are available. All specifications include country fixed effects and controls for gender, age, religion, distance to the capital city, number of protests that occurred within 30 km before the first project was planned, a dummy for cities and a dummy indicating whether the respondent lives in the president's home region. Standard errors are clustered by community.

Our results are substantively smaller but still large and statistically significant when we expand to thirty-eight countries in the left panel of Figure 3. Respondents living near completed Chinese projects are 5 percentage points more likely to believe the former colonial power's model is best (p < 0.01) – an increase of roughly 37 per cent relative to the sample mean (0.13), and of roughly 49 per cent relative to the mean among those living near planned Chinese projects (0.1). These results are consistent with Figure 1, again suggesting that Chinese aid has more positive effects on perceptions of Western countries – even former colonizers – than it does on perceptions of China itself.

Discussion and Conclusion

Our study contributes to research on the strategic effects of aid from geopolitical rivals operating in the same countries at the same time. Focusing on the soft power implications of aid, we find evidence of a substitution effect, but not always in the expected direction. Contrary to concerns raised by prominent members of the US government and foreign policy establishment, we find little or no evidence that Chinese aid enhances Chinese soft power in Africa, diminishes American soft power, increases ideological alignment with China or decreases ideological alignment with the United States. If anything, the opposite appears to be true. Net of potential selection effects, our results suggest that Chinese-funded projects decrease affinity for China and increase affinity for the United States. US-funded projects also appear to increase affinity for the United States. Our results also suggest that US-funded projects strengthen citizens’ commitment to liberal democratic values, while Chinese-funded projects either have no effect on this commitment or strengthen it as well.

Taken together, these findings suggest that aid can serve as an instrument of soft power, but that its effectiveness varies across donors and aid regimes. What explains this variation? Why does Chinese aid to Africa have such weak or even adverse effects on China's soft power? Why does US but not Chinese aid seem to generate support and ideological alignment among citizens of recipient countries? The null or negative impact of Chinese aid on soft power is surprising, given the praise that China has received in at least some African countries, and given the growing number of studies suggesting that Chinese aid is effective in improving public services and infrastructure (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher2016; Wegenast et al. Reference Wegenast2017). China seems to be delivering on its promise to bring development to Africa. Yet our results suggest that this is not translating into greater affinity for China or its political or economic model.

One possibility is that the adverse effects of Chinese aid are a result of particular characteristics of the Chinese aid regime. For example, as discussed above, while China is often credited with investing in high-cost, large-scale infrastructure projects that other donors typically avoid, Chinese firms are often accused of prioritizing speed and low cost at the expense of quality, which may alienate beneficiaries (Hanauer and Morris Reference Hanauer and Morris2014b). Stories about the low quality of Chinese-financed infrastructure projects are common, especially in the media. Whether Chinese projects are actually low quality, or lower quality than US alternatives, is a matter of debate. But as Hanauer and Morris (Reference Hanauer and Morris2014b, 63) note, ‘a plethora of visible and widely publicized examples of poor-quality Chinese work (exaggerated or not) have created the perception that Chinese construction is sub-standard’. For soft power purposes, this perception arguably matters more than the reality.

Chinese aid also tends to be accompanied by an influx of Chinese firms and workers into recipient countries. This has provoked concerns about the loss of land to Chinese laborers, or the loss of enterprise and employment opportunities to Chinese businesses. Wegenast et al. (Reference Wegenast2017), for example, find that in areas around Chinese-owned mines, Africans tend to be particularly concerned about job losses induced by China's activities. A similar dynamic may arise around Chinese aid projects. These concerns tend to be especially acute in areas rich in natural resources, as China is often accused of exploiting African countries in order to extract raw materials for manufacturing. Existing empirical evidence suggests that China does not systematically favor resource-rich countries in the aid it delivers (Dreher et al. Reference Dreher2018), but again, the perception may matter more than the reality. The increasing presence of Chinese citizens may also foment social and cultural tensions between immigrants and locals. As discussed above, it is possible that Chinese ODA would have more beneficial effects if it were delivered independently of these other economic and financial activities. But the line between Chinese ODA and OOF is often intentionally blurred, and we cannot say for certain.

A lack of conditionalities and a willingness to engage with undemocratic governments may also explain why Chinese aid does not appear to induce ideological alignment with the Chinese government. As part of Xi Jinping's ‘five-no’ doctrine, China rejects the push for democratization, liberalization and good governance that characterizes much OECD-DAC aid to the continent. Whereas the United States, the UK and other donors are explicit in their attempts to export liberal democracy, China has not offered an equally explicit alternative other than non-interference, which may not be enough to sway citizens. More direct messaging may be necessary to induce ideological alignment. But this is precisely the sort of messaging that the five-no doctrine is designed to curtail.

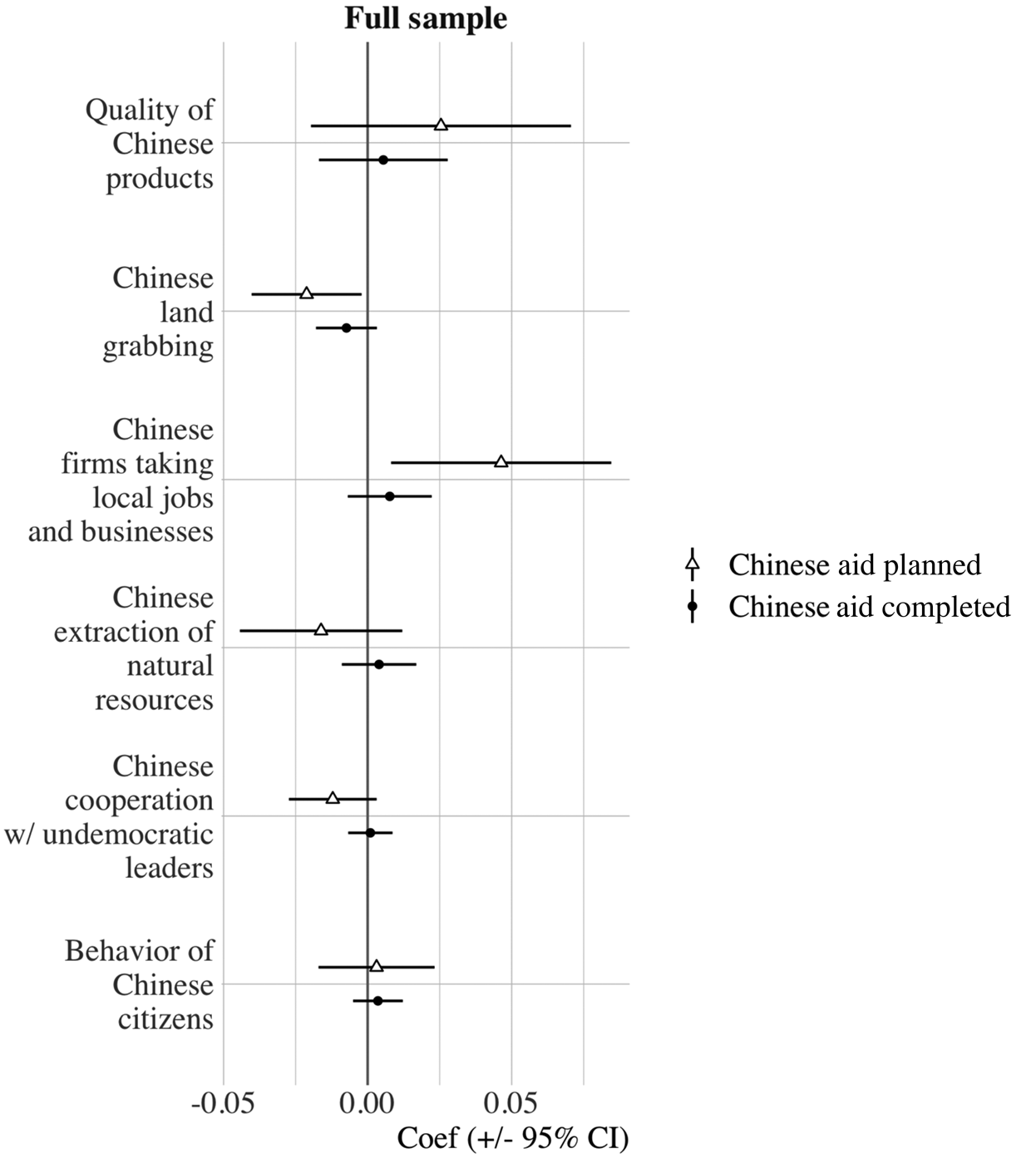

While we cannot definitively adjudicate between these mechanisms, round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey includes two questions that allow us to explore them further. Respondents were asked which factors contribute most to China's positive or negative image in their country. (Unfortunately, the Afrobarometer did not ask analogous questions about the United States.) The list of factors contributing to a positive image includes (1) China's policy of non-interference; its investment in (2) business and (3) infrastructure; (4) its support for the recipient country in international affairs; (5) China's people, culture and language; and (6) the cost of Chinese products. Factors contributing to a negative image include (1) China's extraction of natural resources; (2) its willingness to ‘cooperate with undemocratic rulers’; (3) land grabbing by Chinese businesses or individuals; (4) the behavior of Chinese citizens living in the respondent's country; (5) the quality of Chinese products; and (6) the loss of jobs or businesses to Chinese competition. We code dummies for each of these factors, then test whether respondents who live near completed projects are drawn to, or repelled by, different factors than those who live near planned projects. Importantly, these questions only address the sources of respondents’ approval or disapproval; they do not measure the extent to which respondents approve or disapprove of China's presence overall. (Our earlier analyses address this latter question.)

Figures 4 and 5 report the effects of Chinese aid on the factors contributing to positive and negative images of China, respectively. The specifications are identical to the one in the left panel of Figure 1. (For compactness, we focus on the thirty-eight countries for which AidData data are available but AIMS data are not.) In general, net of potential selection effects, Chinese aid does not appear to affect the features of the Chinese aid regime that respondents find most and least attractive, with a few exceptions. Most notably, across countries, a plurality of respondents cite China's investment in infrastructure as the most important factor contributing to positive images of China. But exposure to Chinese aid appears to dampen this enthusiasm (Figure 4, third row). Respondents living near completed Chinese projects are 9 percentage points less likely to describe China's infrastructure investments as the most important factor contributing to positive images of China (p < 0.001) – a roughly 33 per cent reduction relative to the sample mean (0.26), and a roughly 18 per cent reduction relative to the mean among respondents living planned Chinese projects (0.49).Footnote 22 Exposure to Chinese-funded projects appears to diminish the appeal of what is otherwise the most attractive feature of the country's aid regime (Hanauer and Morris Reference Hanauer and Morris2014b, xii; Lekorwe et al. Reference Lekorwe2016).

Figure 4. Effects of Chinese aid on factors contributing to positive image of China

Notes: coefficients and 95 per cent confidence intervals from OLS regressions using data from round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey. All specifications include country fixed effects and controls for gender, age, religion, distance to the capital city, number of protests that occurred within 30 km before the first project was planned, a dummy for cities and a dummy indicating whether the respondent lives in the president's home region. Standard errors are clustered by community.

Figure 5. Effects of Chinese aid on factors contributing to negative image of China

Notes: coefficients and 95 per cent confidence intervals from OLS regressions using data from round 6 of the Afrobarometer survey. All specifications include country fixed effects and controls for gender, age, religion, distance to the capital city, number of protests that occurred within 30 km before the first project was planned, a dummy for cities and a dummy indicating whether the respondent lives in the president's home region. Standard errors are clustered by community.

To explore this relationship further, in Appendix O we distinguish infrastructure projects from all other types of projects in AidData, then test whether the apparent adverse effects of Chinese aid on citizens’ perceptions of China are especially strong for infrastructure projects. Consistent with our results in Figure 4, we find that Chinese infrastructure projects in particular appear to have a net negative effect on perceptions of China and the Chinese model of political and economic development, and a net positive effect on perceptions of the United States. Non-infrastructure projects appear to have no net effect on perceptions of either China or the United States. While this analysis requires stretching AidData rather thin, and should therefore be interpreted with some caution, it suggests that China's focus on infrastructure may have the unintended adverse effect of alienating beneficiaries.

Questions remain. In particular, what aspects of Chinese infrastructure investments are responsible for the negative reactions of citizens who are affected by them? Chinese aid does not appear to aggravate concerns about loss of land, jobs or businesses to Chinese competition; nor does it appear to exacerbate complaints about the quality of Chinese products (Figure 5) – though, importantly, this latter question does not distinguish between the quality of Chinese infrastructure and the quality of all other Chinese products. It may be that citizens of recipient countries are disillusioned by the impact of Chinese infrastructure investments on their quality of life, and that this disillusionment reduces their affinity for the Chinese model of development more generally – and increases their affinity for the American alternative. It is also possible that more disaggregated data will reveal nuances that our analyses above cannot detect. We view this as a potentially promising avenue for future research to explore.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000193.

Data availability statement

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HEZ7ZV.

Acknowledgements

For helpful comments, we thank Jeff Colgan, Lucy Martin, Brad Parks, Matt Winters, the AidData team and three anonymous reviewers. For their excellent research assistance we thank Omar Afzaal, Omar Alkhoja, Paul Cumberland, Lucas Fried and Toly Osgood.

Financial support

This research was funded by the Institute of International Education (IIE), under the Democracy Fellows and Grants Program (AID-OAA-A-12-00039), funded by USAID's Center of Excellence in Democracy, Human Rights, and Governance (DRG Center). The content of this research does not necessarily reflect the views, analysis, or policies of IIE or USAID; nor does any mention of trade names, commercial products or organizations imply endorsement by IIE or USAID.