Economic inequality has reached its highest levels in 30 years in advanced industrial societies. Since the mid-1980s, the Gini coefficient has grown by a total of 3 points. The richest 10 per cent now earn 9.5 times more than the bottom 10 per cent, up from 7 times more in the mid-1980s. Citizens have also become increasingly aware of inequality. In 2013, 85 per cent of Europeans believed that the gap between the rich and the poor had increased, and 60 per cent agreed that inequality was a ‘very big’ problem; 62 per cent of Americans considered the economic system unfair (OECD 2014; Pew 2013; Pew 2014).

At the same time, immigration has been a prominent issue in the refugee crisis, Brexit, and recent elections in the United States and Europe. On average, 5 per cent of Americans have mentioned immigration as the most important political problem each year since 2001, but the number jumped to 22 per cent in 2018, surging to the top of the list. Between 2005 and 2017, the share of Europeans considering immigration a top priority grew from 14 to 39 per cent. And in a 2017 survey conducted in 25 countries, 49 per cent of respondents agreed that immigrants were placing too much pressure on public services, compared to 19 per cent who disagreed; 62 per cent of Americans also supported excluding new immigrants from welfare benefits (Gallup 2018; Eurobarometer 2017; Ipsos 2017; Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2017).

These data reveal that immigration is salient in advanced democracies, especially in the politics of welfare, and that many citizens are concerned about economic inequality. Inequality increases the stakes of redistribution and often puts those who pay for it at odds with those who benefit. But what happens when different groups enter the picture as potential recipients? How does inequality affect support for redistribution to native citizens as opposed to immigrants?

While prior studies have explored the relationship between competition over scarce resources and hostility toward immigrants (Citrin et al. Reference Citrin1997; Dancygier and Donnelly Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2012), the impact of economic inequality on support for immigrants has received less attention. Previous work on preferences for redistribution has examined the separate effects of inequality (Kuziemko et al. Reference Kuziemko2015; Lupu and Pontusson Reference Lupu and Pontusson2011; Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2016; Shayo Reference Shayo2009; Trump Reference Trump2018) and immigration (Alesina, Miano, and Stantcheva Reference Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva2018; Brady and Finnigan Reference Brady and Finnigan2014; Mau and Burkhardt Reference Mau and Burkhardt2009). Yet we know little about how inequality and immigration interact to affect welfare support.

Furthermore, while individuals exhibit different attitudes depending on the social policies under consideration (Ballard-Rosa, Martin, and Scheve Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017; Cavaillé and Trump Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015; Holland Reference Holland2018; Moene and Wallerstein Reference Moene and Wallerstein2001; Munoz and Pardos-Prado Reference Muñoz and Pardos-Prado2019) and the identity of welfare recipients (Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2017; Bobo and Kluegel Reference Bobo and Kluegel1993; Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Luttmer Reference Luttmer2001; Rueda Reference Rueda2018), most of the comparative literature on inequality focuses on support for general redistribution. As a result, it is not clear what groups benefit from (or are penalized under) inequality.

This article argues that economic inequality triggers selective solidarity. When inequality is high, individuals grow more supportive of redistribution – but only if redistribution benefits native citizens. Inequality therefore reinforces the already popular opinion that native citizens deserve welfare priority over immigrants and widens the gap between support for natives and support for immigrants. This happens because inequality erodes beliefs in the existence of economic opportunity that is conducive to social mobility, which in turn strengthens in-group favoritism. If citizens think that external factors rather than hard work determine one's economic fate, they become more selective regarding who should receive government support – and more likely to prioritize natives.

I offer evidence for my argument combining cross-national observational analysis with an original survey experiment. This approach allows me to evaluate attitudes in a large sample of countries and to isolate causally identified effects. The observational analysis links European Social Survey (ESS) data to contextual socio-economic indicators, including a measure of economic inequality that takes into account the large subnational variation. The results reveal a strong negative correlation between inequality and support for welfare redistribution to immigrants.

I then present the results of a survey experiment administered to a nationally representative sample of 1,275 Italian citizens, in which I prime participants to think about inequality. Exposure to objective information about inequality significantly increases support for redistribution through higher taxes on the rich (+11 percentage points) and income subsidies for native citizens (+7 percentage points), but does not boost respondents’ willingness to help immigrants. In fact, among conservatives, inequality reduces support for subsidies for immigrants by 17 percentage points.

This study bridges the fields of political economy and political psychology by unpacking the relationship among economic inequality, immigration and support for redistribution. Specifically, it shows how inequality leads to selective solidarity by influencing a psychological component – the erosion of beliefs in social mobility. Furthermore, the fact that welfare recipients' identity powerfully shapes the impact of inequality helps explain why prior comparative scholarship on inequality and preferences for redistribution – which has usually focused on general redistribution – has produced inconsistent results.

More generally, my findings suggest a possible micro-foundational explanation for the increased support for populist radical right parties in times of growing economic disparity. By spurring welfare chauvinism as a product of despair over the perceived lack of opportunity, inequality can favor the success of parties that often embrace nativist positions.

Previous work: Economic Inequality, Identity and Redistribution

The study of the impact of economic inequality on pro-social behavior has a long history. Plato believed that inequality generates divisions between the rich and the poor and causes the rich to neglect their responsibilities (Plato [and Adam] Reference Plato and Adam2011). Aristotle suggested in Politics that inequality reduces solidarity by making individuals concerned about their short-term self-interest and by pitting the rich against the poor (Aristotle Reference Aristotle and Lord2013, Pol. 1295b; Tranvik Reference Tranvikn.d.). In his Discourse on the Origins of Inequality, Rousseau warned that inequality leads to fragmented societies where the rich are less inclined to help the poor (Rousseau and Gourevitch Reference Rousseau and Gourevitch1997, 137, 171, 185). While Adam Smith believed that moderate inequality boosts political stability, he also worried that high levels of inequality diminish citizens’ willingness to help the disadvantaged (Rasmussen Reference Rasmussen2016; Smith Reference Smith, Raphael and Macfie1982, I.iii.2, 50–61).

Modern social science has extensively explored the link between economic inequality and redistribution. The median voter theorem suggests that higher market income inequality favors greater support for redistribution, because the distance between average income and the median voter's income is greater in more unequal societies (Meltzer and Richard Reference Meltzer and Richard1981; Romer Reference Romer1975).

Empirical work on the impact of economic inequality on preferences for redistribution, however, has yielded mixed results. Some studies find that inequality increases support for redistribution (Finseraas Reference Finseraas2009; Tóth and Keller Reference Tóth and Keller2011). This happens especially among the rich, who become more altruistic as a result of rising crime, which is a negative externality of inequality (Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016; Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2016).

Other studies find that inequality has no effect on preferences for redistribution (Kenworthy and McCall Reference Kenworthy and McCall2008; Kuziemko et al. Reference Kuziemko2015; Lübker Reference Lübker2007; Trump Reference Trump2018; Trump and White Reference Trump and White2018), or that its effect is conditional on the structure rather than the level of inequality (Lupu and Pontusson Reference Lupu and Pontusson2011). Still others show that inequality reduces support for redistribution (Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis2000; Paskov and Dewilde Reference Paskov and Dewilde2012), specifically among higher-income individuals (Côté, House and Willer Reference Côté, House and Willer2015) and when economic disparity is more visible (Nishi et al. Reference Nishi2015). Consistently, Larsen (Reference Larsen2006; Larsen Reference Larsen2008) finds that individuals in liberal and conservative welfare regimes – characterized by higher levels of inequality – have more negative welfare attitudes.

One reason why previous studies have produced inconsistent outcomes is that they have usually focused on support for general redistribution rather than for specific policies. Redistribution, however, can elicit different attitudes depending on the social groups that are thought to benefit (Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva Reference Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva2018; Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2017; Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve Reference Ballard-Rosa, Martin and Scheve2017; Muñoz and Pardos-Prado Reference Muñoz and Pardos-Prado2019; Rueda Reference Rueda2018). In the United States, for instance, welfare has become racially coded and associated with blacks among large subsets of the white electorate (Gilens Reference Gilens1999), while Social Security is linked to whiteness (Winter Reference Winter2006).

As a result, the effect of inequality on welfare preferences depends on which recipients are targeted by particular redistributive measures (Moene and Wallerstein Reference Moene and Wallerstein2001). When they consider redistributive policies, individuals tend to differentiate between those that ‘take from the rich’ and those that ‘give to the poor’. Since the latter are more likely to generate other-oriented social affinity considerations rather than self-oriented income maximization (Cavaillé and Trump Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015), welfare recipients' identity likely critically shapes the effects of inequality on preferences for redistribution to low-income receivers.

What forms of identity are relevant in the politics of welfare? Individuals tend to display parochial altruism: they are prone to help members of their community but deny support to out-groups (Bernhard, Fischbacher and Fehr Reference Bernhard, Fischbacher and Fehr2006; Bowles and Gintis Reference Bowles and Gintis2013; Marks Reference Marks2012). Race and immigration often define the community boundaries. Support for welfare increases in the United States as the number of recipients of the same race grows (Bobo and Kluegel Reference Bobo and Kluegel1993; Luttmer Reference Luttmer2001), while welfare attitudes are more negative in racially heterogeneous societies (Alesina and Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2009).

In Europe, where immigration rather than race is salient (Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe, Marks and .2018), individuals are more in favor of welfare support for native citizens than for immigrants (Reeskens and van Oorschot Reference Reeskens and Van Oorschot2012; Van der Waal et al. Reference Van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, De Koster and Manevska2010). Feelings of economic competition (Burgoon, Koster and Van Egmond Reference Burgoon, Koster and Van Egmond2012; Dancygier and Donnelly Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2012) or cultural and racial hostility (Ford Reference Ford2016) can drive such attitudes. These factors help explain why higher levels of immigration often predict lower levels of support for the welfare state (Dahlberg, Edmark and Lundqvist Reference Dahlberg, Edmark and Lundqvist2012; Eger Reference Eger2009; Mau and Burkhardt Reference Mau and Burkhardt2009).

While previous scholarship shows that ethnic diversity and immigration increase feelings of competition and negatively affect support for redistribution (Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva Reference Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva2018), we do not know whether these sentiments are more common when economic inequality is high.Footnote 1 Considering that inequality raises the stakes of redistribution and that immigration is relevant in the politics of welfare, it is important to understand how economic disparity affects individuals’ willingness to help different groups in society. The next section develops a theory that links economic inequality to welfare redistribution to native citizens and immigrants.

Theory: Inequality, Immigrants and Selective Solidarity

To understand how macro-level factors influence micro-level behavior, we need to consider how individuals react to the context in which they live. Social identity theory posits that individuals tend to see themselves as members of groups in society, and that they strive to maintain a positive social identity. Such an identity is based on a favorable comparison between the in-group and relevant out-groups (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979; see also Shayo Reference Shayo2009).

What are the relevant groups in the context of economic inequality and redistribution? For a start, we can distinguish between those who pay for redistribution and those who benefit from it – a basic distinction consistent with people's empirical disposition to differentiate between redistribution ‘from the rich’ and ‘to the poor’ (Cavaillé and Trump Reference Cavaillé and Trump2015).

Survey data show that a vast majority of citizens are unsatisfied with the current level of income distribution: 62 per cent of Americans judge the economic system as unfair, while 60 per cent of Europeans agree that inequality is a ‘very big’ problem and 77 per cent that the economic system favors the wealthy (Pew 2013, 2014). Dissatisfied individuals strive to improve their condition, and social identity theory suggests social mobility as a possible response (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). Indeed, individuals ‘physically crave to be higher than others on the status ladder’ (Payne Reference Payne2017, 45).Footnote 2

However, I argue that social mobility is perceived to be less viable when economic inequality is high. Under high inequality, income is concentrated in the hands of fewer individuals, and a larger number is in a relatively worse position. The increased distance between the top and the rest highlights the economic advantage of the wealthy and emphasizes the contrast between the super-rich and the rest. Economic hierarchy becomes more apparent (Newman, Johnston and Lown Reference Newman, Johnston and Lown2015). In this framework, inequality depresses the likelihood of upward mobility and favors the transmission of economic advantage (Chetty et al. Reference Chetty2014; Corak Reference Corak2013), and erodes trust in the role of individual effort in getting ahead in life (McCall et al. Reference McCall2017).

Hence, I anticipate that, when economic inequality is high, citizens lose faith in the existence of opportunities to climb the social ladder. Under deep inequality the steps of the ladder grow further apart (Chetty et al. Reference Chetty2014), and moving up those steps appears prohibitive, as if people were climbing skyscrapers rather than human scales (Payne Reference Payne2017, 28–29). Hard work is thus no longer seen as a guarantee of economic success.

I expect this belief to be widespread because the increase in inequality in recent decades has been strongly top-skewed (Atkinson, Piketty and Saez Reference Atkinson, Piketty and Saez2011; Volscho and Kelly Reference Volscho and Kelly2012). Top-skewed inequality ‘makes people feel poor […] even when they are not’ (Payne Reference Payne2017, 4) and makes them less likely to identify with the rich (see also Lupu and Pontusson Reference Lupu and Pontusson2011). Indeed, only 1 per cent of Europeans and 2 per cent of Americans consider themselves as members of the higher class (Eurobarometer 2016; Pew 2012). For these reasons, inequality erodes beliefs in social mobility for the vast majority of citizens – even among the relatively wealthy who do not see themselves as belonging to the super-rich who have benefited from growing inequality. Hence:

Hypothesis 1: Economic inequality weakens belief in the existence of economic opportunities that are conducive to social mobility.

A lack of social mobility generates dissatisfaction with social stratification (Newman Reference Newman1989). Social identity theory suggests an alternative response for dissatisfied individuals when social mobility does not look attainable: social competition – that is, a response that targets the relevant out-group. When people do not think citizens can climb the social ladder and improve their situation through personal effort, they become more likely to back measures that redistribute resources away from the top.

By depressing beliefs in social mobility, I therefore expect inequality to increase support for redistribution. De Tocqueville (Reference De Tocqueville2003[1835]) hypothesized that different mobility rates distinctively shaped attitudes toward redistribution in Europe and the United States. Several studies have since shown that citizens are more likely to support redistribution when they have experienced limited social mobility or do not expect future upward mobility (Alesina and LaFerrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2005; Benabou and Ok Reference Benabou and Ok2001; Piketty Reference Piketty1995).

But the effects of social mobility are not limited to direct personal experience. General beliefs about the determinants of one's position on the social ladder also influence redistribution attitudes. Lipset and Bendix (Reference Lipset and Bendix1959) suggested that different perceptions of class rigidities helped account for the diversity in preferences for redistribution in Europe and the United States. A vast literature later explained that people who do not believe that hard work leads to economic success exhibit greater support for redistribution (Alesina and LaFerrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2005; Corneo and Grüner Reference Corneo and Grüner2002; Giuliano and Spilimbergo Reference Giuliano and Spilimbergo2014; Piketty Reference Piketty1995). This also applies to individuals who are personally wealthy and unlikely to benefit from redistribution (Fong Reference Fong2001).Footnote 3 Hence:

Hypothesis 2: By depressing beliefs in opportunities for social mobility, economic inequality increases support for redistribution.

Not everyone, however, is seen as equally deserving of welfare support. I expect economic inequality to intensify in-group favoritism. By separating the rich from the rest, inequality activates in-group/out-group thinking, a disposition to see the world in ‘us against them’ terms (Kinder and Kam Reference Kinder and Kam2010). As generalized in-group bias rather than hostility directed at a specific out-group (Brewer and Campbell Reference Brewer and Campbell1976; Kinder and Kam Reference Kinder and Kam2010), this ‘us against them’ thinking extends to groups other than the rich.

Immigration, in particular, provides an ‘encompassing distinction’ between those who are citizens of the (welfare) state – and therefore in-group members – and non-citizens – hence, members of the out-group (Reeskens and Van Oorschot Reference Reeskens and Van Oorschot2012, 122). Communal boundaries have historically delimited the welfare state, generating a strong linkage between welfare, nationality and citizenship, especially in Europe (Kymlicka Reference Kymlicka2001; Miller Reference Miller1999; see also Hooghe and Marks Reference Hooghe and Marks2005). As a result, people often consider immigrants to be less deserving of welfare than native citizens (Ford Reference Ford2016; Van Oorschot Reference Van Oorschot2006). Large sectors of the electorate also embrace welfare chauvinism, an attitudinal position that aims to reserve welfare services for native-born citizens (Cavaillé and Ferwerda Reference Cavaillé and Ferwerdan.d.; Kitschelt Reference Kitschelt2007; Van der Waal et al. Reference Van der Waal, Achterberg, Houtman, De Koster and Manevska2010; Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot Reference Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot2013).

By inducing the belief that citizens lack opportunities to improve their condition through personal effort, I expect inequality to make individuals more discriminating regarding who should receive help. Inequality therefore strengthens the already popular opinion that native citizens should be prioritized to receive welfare over immigrants. Reserving welfare for natives under high levels of inequality ensures that resources are channeled to more deserving recipients during times when external factors seem to have a greater influence than individual control in determining one's economic fate. If natives are not given a fair shot to improve their condition through hard work, they should at least be prioritized in the distribution of government support.Footnote 4

Hypothesis 3: By depressing beliefs in opportunities for social mobility, economic inequality generates selective solidarity, that is, it increases the gap in welfare support for natives vs. immigrants.

Theory Summary

By highlighting the contrast between the rich and the rest, inequality erodes beliefs in social mobility. The perceived lack of opportunity for individuals to improve their condition, in turn, increases support for redistribution. However, not everyone is considered equally deserving of welfare support. Inequality, in fact, widens the gap between willingness to help native citizens and willingness to help immigrants. In times of perceived lack of opportunity, people become more likely to prioritize natives, who are seen as more deserving of welfare than immigrants (Figure 1).

Figure 1. From economic inequality to selective solidarity

Data and Methods

To test my hypotheses, I use ESS data for thirteen Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, which I link to contextual socio-economic indicators. The cross-national analysis allows me to explore the correlation between inequality and preferences for redistribution in a large sample of countries. There are, however, limitations in such analysis, especially with regard to identification and causality. Moreover, some of the survey items are imprecise measures of the concepts of interest and no variable is available to test the mechanism based on perceived lack of opportunity.

I address these shortcomings by complementing the observational analysis with an original survey experiment administered to a nationally representative sample of Italian citizens. The experiment allows me to evaluate the causal effect of exposure to information about inequality on support for welfare policies benefiting natives and immigrants. Furthermore, I can explore the causal mechanism behind the effect.

Italy is a conservative test for my theory. On the one hand, it is representative of the level and dynamics of income inequality in OECD countries.Footnote 5 Immigration is also a central concern, as it is in most European democracies: 49 per cent of Italians in 2016 and 39 per cent in 2017 considered immigration the most important issue faced by the European Union (EU), compared to averages of 45 per cent and 38 per cent, respectively, across all EU member states.Footnote 6

On the other hand, beliefs in meritocratic opportunity for social mobility are especially weak in Italy. Italians are more likely than other OECD citizens to consider connections and family background as important determinants of economic success. Data from twenty-nine countries in the International Social Survey ProgramFootnote 7 reveal that the percentage of Italians who believe that hard work is important to get ahead in life is 11 points lower than the OECD average (64 per cent vs. 75 per cent). Compared to OECD citizens, Italians are more likely to attribute economic success to coming from a wealthy family (37 per cent vs. 26 per cent), having political connections (43 per cent vs. 21 per cent) and knowing the right people (59 per cent vs. 51 per cent). In a context where the faith in meritocracy is already weak, the expectation that the inequality treatment will further erode beliefs in meritocratic opportunity for social mobility is highly demanding.

A Cross-National Analysis of the Effects of Inequality

I merge survey data from the ESS with macro socio-economic variables. I focus on the thirteen OECD countries in the 2008 ESS wave for which the measure of inequality is available.Footnote 8 I use the 2008 wave because it presents a rich module on welfare state attitudes and because the measure of inequality is available for the years 2002–2009. Given the hierarchical structure of the data, I run multilevel random-effect models with varying intercepts.Footnote 9

Economic inequality is measured by the regional Gini index (Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2016), which ranges from 0 (a condition of perfect equality) to 1 (a condition of absolute inequality). Focusing on the sub-national level allows me to account for the substantial regional differences in inequality and welfare preferences observed in many European countries. For instance, in Spain, the Cantabria region has a Gini value of 0.22, the lowest in the entire sample, while Castilla-La Mancha has a Gini value of 0.37, which is higher than the value corresponding to the third quartile. Residents of Cantabria exhibit low support for people in need (3.17), while residents of Extremadura are much more supportive (4.15, a whole point higher on a five-point scale). Support for immigrants in Germany ranges from 2.4 in Brandenburg to 3.3 in Bremen (on a five-point scale).

I adopt two separate dependent variables, one measuring general support for individuals facing economic hardship and the other capturing welfare support for low-income immigrants. Regarding help for people in need, higher values correspond to the belief that benefits for the poor are insufficient.Footnote 10 The wording of the survey item is especially fitting because it mentions respondents' country of residence, which should emphasize considerations related to their national identity (see Kuo and Margalit Reference Kuo and Margalit2012). Willingness to provide economic help to immigrants is measured by an item focused on support for the provision of welfare services to immigrants. Greater values indicate greater willingness to support immigrants.Footnote 11

The models include controls at the individual, regional and national levels. Regarding individual variables, the first model presents basic socio-demographic indicators that may affect preferences for redistribution. In addition to gender, age and education, I control for income using a measure based on deciles so that it is comparable across countries, political ideology (where 0 corresponds to left and 10 to right), and religiosity.

The second model adds controls for union membership, employment status, household size and age squared (displayed in Appendix Table A1 due to space constraints). It also controls for socio-economic perceptions and attitudinal positions. I consider feelings of economic security, which are often negatively related to welfare support (Ford Reference Ford2016); inequality evaluations; poor and immigrant deservingness, an important determinant of welfare support (Petersen Reference Petersen2012); general economic and cultural attitudes toward immigrants; and the perceived size of the poor and immigrant populations, which measure both the perceived spread of need and the possible costs of assistance (see Appendix Table A1).Footnote 12

Additionally, all the models include regional controls to isolate the impact of inequality from other subnational indicators. GDP per capita and the unemployment rate control for general economic conditions, since both support for redistribution and hostility toward immigrants may be higher during economic hardship. Population density accounts for the possibility that individuals who live in urban areas exhibit different preferences. I also control for the share of foreigners, given the often-negative link between ethnic heterogeneity and support for the welfare state (Alesina and Glaeser Reference Alesina and Glaeser2004; Finseraas Reference Finseraas2009).

The third model includes national-level socio-economic indicators – average GDP per capita, social expenditure, unemployment rate and share of foreigners.Footnote 13 Table 1 reports some individual controls, and Appendix Table A1 reproduces the full model specifications.

Table 1. Welfare support for people in need and immigrants

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Models 1 through 3 show that higher levels of inequality are correlated with a lower willingness to provide support to people in need, even after controlling for numerous individual and contextual indicators. However, Models 4–6 reveal that the average willingness to provide economic help to immigrants decreases as inequality grows.

The negative effect of inequality on support for people in need and for welfare for immigrants is substantial. According to the predicted values from Models 1 and 4, respectively, the difference in support between an average individual living in the most equal region and a citizen living in the most unequal region is roughly similar to the difference in predicted support between an individual with the lowest level of education and one with the highest level, and between two citizens at opposite extremes of the political ideology scale. The robustness of these findings is quite remarkable if one considers that inequality remains significant even after controlling for feelings of undeservingness of the poor (Models 2 and 3) and immigrants (Models 5 and 6), and for individual economic and cultural attitudes toward immigrants (Models 5 and 6).

This analysis, therefore, shows a correlation between economic inequality, on the one hand, and two contrasting attitudes, on the other: general support for people facing economic difficulty and a desire to tighten immigrant access to social benefits. The following section presents the results of the survey experiment, which allows me to isolate the causal effect of inequality on support for welfare policies benefiting native citizens vs. immigrants.

Survey Experiment

I conducted a survey experiment with a nationally representative sample of 1,275 Italian citizens.Footnote 14 After providing information on their age and gender and confirming that they resided in Italy, respondents were randomly assigned to one of three conditions – the economic inequality treatment, the poverty treatment or the control group.

The inequality and poverty treatments primed respondents to think about inequality and poverty in Italy, respectively, and were built symmetrically. They presented two pages providing objective information about economic inequality and poverty in the country with bullet-point data summary, graphs and pictures (see Appendix Figures B1 and B2). The poverty treatment is not the focus of this article, but it allows me to test whether the effect of inequality (that is, unequal resource distribution between the top and bottom portions of the income distribution) differs from the effect of a focus on the lack of resources for the bottom.

The first page of the inequality treatment described the level of economic inequality in Italy and contrasted the income and wealth of the top 1 per cent with that of the rest of the population. A plot also showed the income distribution by quintile. The second page contained information about the growth of inequality in the country and compared wealth accumulation and income trends for the top and the rest since 2000. The second page also presented two pictures that contrasted a wealthy individual in front of an expensive car and a luxury house with a lower-income individual looking for food among surplus products at a city food market.

Similarly, the first page of the poverty treatment presented information on the level of poverty in Italy and a plot showing the number of poor who cannot afford basic services. The second page reported data on the increase in poverty over the last two decades, in addition to a picture depicting a lower-income individual looking for food at a city market.

Respondents in the treatment groups were instructed to carefully read the information provided before answering questions, while those in the control group started answering questions right away. I gauged welfare attitudes in two ways. First, I measured support for redistribution that takes away from the rich. To emphasize the cost of redistribution for the rich, the survey item asked respondents the extent to which they agreed or disagreed with the following statement: ‘The government should increase taxes on the rich to decrease income differences in Italy.’

Secondly, I focused on policies that distribute to those in need by measuring support for monthly income subsidies for natives and immigrants: ‘How much are you in favor of or against a government intervention to promote the following policies, even if such intervention required a tax increase or a spending cut in other sectors? Providing a payment card of 350 euros per month for food, health and bills-related expenses to Italian citizens who live in absolute poverty [to immigrants who live in Italy in absolute poverty]?’ The only difference in the questions about this policy, which is in place in Italy, was recipients' identity. The order of the questions was randomized across respondents.

To investigate the mechanism through which inequality shapes welfare preferences, I included an item that measured beliefs in economic opportunity conducive to social mobility, captured by the perceived importance of hard work in improving one's economic condition. In the second part of the survey, respondents answered questions about their socio-economic situation and political preferences. The post-experiment questionnaire also included manipulation and attention checks. The manipulation checks confirmed that the two treatments increased awareness of inequality and poverty, respectively (see Appendix Tables B1–B3).Footnote 15

Experimental Findings

Below I present the results of the analysis based on the entire sample. The Appendix reports the analyses run with the subset of respondents who passed the attention check and the subset that excludes the 5 per cent fastest and slowest respondents. The results remain substantively unchanged.

Redistribution that Takes Away from the Rich

Exposure to information about inequality significantly increases support for redistribution that takes away from the rich. While 40.9 per cent of respondents in the control group agree that taxes on the rich should be raised to reduce income differences, this share is 51.4 per cent in the inequality group. By contrast, the impact of the poverty treatment is positive but insignificant: 43.3 per cent of respondents strongly agree on the need to raise taxes on the rich (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Support for redistribution

Table 2 reports the results of ordinary least squares (OLS), logit and ordered-logit models with and without controls (due to space constraints, the controls in this and the following tables are shown in Appendix Tables B4 and B5).Footnote 16 All the model specifications confirm that inequality increases support for redistribution through higher taxes on the rich. When controls are included, inequality produces a 14-percentage-point increase in support for higher taxes on the rich (Model 2).

Table 2. Support for redistribution

Note: the models in this and the next tables include the following covariates: gender, age, education, household income, economic ideology, social ideology, party ID and location of residence. Control mean reports the mean of the outcome variable for the control group. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Appendix Table B4 also shows that, as expected, richer and economically conservative individuals display significant opposition to redistribution. The effect of inequality is about one-third the size of the effects of income and political ideology – arguably a relatively strong impact for an informational treatment.

By contrast, the impact of the poverty treatment is not significant. One possible explanation is that the inequality treatment – which highlights the resource imbalance between the top and bottom – leads participants to focus on the very rich at the top, while the poverty treatment – which emphasizes the lack of resources for the bottom – focuses on the have-nots. If this is the case, inequality may make the majority of respondents feel poor compared to the top (Payne Reference Payne2017) in a way that the poverty treatment that clearly separates the majority from the bottom does not. Recent experimental work finds that changes in people's social comparisons modify political opinions. Individuals who feel comparatively poorer become more supportive of redistribution, while those who feel relatively rich show decreased support (Brown-Iannuzzi et al. Reference Brown-Iannuzzi2015). Under inequality, therefore, even relatively affluent respondents exposed to the super-rich may favor greater redistribution.

Welfare Redistribution to Natives vs. Immigrants

What is the impact of inequality on support for welfare redistribution to natives and immigrants? Inequality – but not poverty – significantly increases individuals’ willingness to redistribute to low-income natives: 48.6 per cent of respondents in the inequality group strongly supported monthly income subsidies for low-income natives, compared to 41.8 per cent in the control group and 43.8 per cent in the poverty group.

However, despite the low level of baseline support for immigrants (and therefore room for increase), inequality does not promote greater willingness to provide redistribution to immigrants. The shares of respondents who strongly back income subsidies for immigrants are 9.9 per cent in the inequality group, 7.8 per cent in the control group and 6.6 per cent in the poverty group. The differences across control and treatment groups are not statistically significant (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Support for low-income native Italians and low-income immigrants

Table 3 reports OLS, logit and ordered logit models. The models confirm that inequality increases willingness to support low-income natives (Models 1–6), but does not have a significant effect on willingness to help immigrants (Models 7–12). In the OLS model with controls (Model 2), exposure to information about inequality increases support for welfare redistribution to natives by 9 percentage points. The full specifications (presented in Appendix Table B5) show that women and lower-income respondents are more in favor of welfare for natives, while supporters of Lega – a party promoting nativism – strongly oppose welfare for immigrants.

Table 3. Support for welfare policies benefiting natives and immigrants

+p < 0.1; *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Selective Solidarity

To offer further evidence, I now code individual responses as ‘response patterns’. My argument, which focuses on the individual level, claims that individuals exposed to inequality simultaneously show stronger support for redistribution away from the rich and to natives and greater opposition to redistribution to immigrants. Hence, to verify that these results are not driven by separate groups of respondents, I now consider response patterns rather than separate preferences.

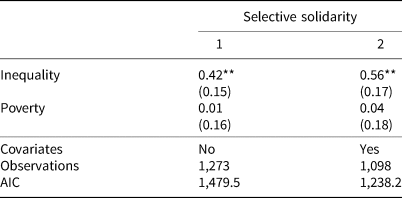

I adopt a dependent binary variable, Selective Solidarity, which equals 1 for respondents who expressed both support for redistribution away from the rich and support for redistribution to natives and opposition to redistribution to immigrants. It equals 0 for the other respondents. Table 4, which presents logit models with and without controls, shows that inequality promotes selective solidarity. Individuals who are exposed to inequality become more likely to support redistribution to natives and, at the same time, oppose redistribution to immigrants.Footnote 17

Table 4. Selective solidarity

**p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Overall, these results provide evidence that inequality increases support for redistribution, but only for policies that benefit native citizens. Exposure to information about economic inequality, therefore, widens the gap in support for welfare redistribution to natives vs. immigrants.

Causal Mechanism: Perceived lack of Economic opportunity and Welfare Deservingness

Why does inequality spark these reactions? To explore the causal mechanism, I first run separate models and then causal mediation analysis. Table 5 evaluates the effect of inequality on perceptions of economic opportunity and examines the impact of the perceived lack of opportunity on welfare support. Model A is a logit model in which the binary dependent variable equals 1 for respondents who disagree that one can improve their economic condition through hard work. Models B1, B2 and B3 are ordered logit in which the main independent variable is lack of opportunity and the dependent variables are the indicators of welfare support presented above.

Table 5. Inequality, lack of opportunity and welfare preferences

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Economic inequality – but not poverty – significantly increases the conviction that society lacks economic opportunity. In turn, believing that society is not offering a way for those at the bottom to improve their condition increases support for redistribution that takes away from the rich and for welfare programs that benefit native citizens, but decreases the willingness to help immigrants through welfare support.

Causal mediation analysis tests more systematically whether beliefs about the lack of opportunity mediate the impact of inequality on welfare preferences. In the analysis, inequality is the treatment, lack of economic opportunity the mediator, and support for redistribution (or for welfare policies benefiting low-income natives or low-income immigrants) the outcome. Since I treat all the outcomes as binary, the effects should be interpreted as the change in the probability that respondents will support the policy under consideration.Footnote 18

The results (reported in Appendix Tables B7 and B8) reveal that the average causal mediation effect (ACME) is statistically significant at the 0.05 level in all three analyses. ACME is positive for support for redistribution and low-income natives and negative for support for low-income immigrants. Inequality therefore negatively influences perceptions of economic opportunity, which in turn have a significant and positive (for redistribution and natives) and negative (for immigrants) effect on welfare support. Regarding the negative impact on welfare for immigrants, the proportion of the total effect of inequality mediated by lack of opportunity is about 20 per cent.

Further analysis also shows that the inequality-induced perceived lack of opportunity strengthens the opinion that natives should receive priority over immigrants in welfare access (see Appendix Tables B9–B12). By depressing belief in social mobility, therefore, inequality reinforces the link between native citizenship and welfare deservingness.

Alternative Explanations? Identity, Altruism and Material self-interest

My argument claims that inequality depresses beliefs in the existence of economic opportunities, which in turn activates an identity conflict between an individual's in-group and out-groups over welfare deservingness. Other theories could explain selective solidarity under inequality. To evaluate my argument against alternative accounts, I consider the testable implications they generate.

I explained that inequality activates in-group/out-group thinking, with the targeted out-groups including the rich and immigrants in the context of welfare redistribution. While humans are naturally predisposed to think in terms of ‘us against them’ and to display in-group favoritism, some individuals hold stronger latent ethnocentric positions (Kinder and Kam Reference Kinder and Kam2010). Such people are more likely to react negatively to immigrants when in-group/out-group thinking is activated. Who are these individuals? Socially conservatives show greater in-group attachment and endorse the in-group/loyalty moral foundation more strongly (Graham, Haidt and Nosek Reference Graham, Haidt and Nosek2009). They are also generally more nationalistic and have more negative attitudes toward immigrants (Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2007; Hooghe, Marks and Wilson Reference Hooghe, Marks and Wilson2002). An implication of my argument, therefore, is that inequality should promote selective solidarity to the detriment of immigrants especially among conservatives.

Other theories emphasize the importance of income as a factor shaping the effect of inequality. Recent comparative studies on inequality and preferences for redistribution argue that inequality increases support for redistribution among the rich (Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016; Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2018; Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2016). Group heterogeneity also seems to affect redistribution preferences only among high-income citizens (Rueda Reference Rueda2018). A testable implication of these studies, therefore, is that the rich are more responsive to inequality, especially when redistribution benefits immigrants.

Other studies on inequality and redistribution attitudes focus on material self-interest and concerns about relative position. Individuals negatively react to inequality because they care about their rank in the income distribution (Fehr and Schmidt Reference Fehr and Schmidt1999), worry about relative living standards (Corneo and Grüner Reference Corneo and Grüner2002) and exhibit last-place aversion (Kuziemko et al. Reference Kuziemko2014). These studies generate two testable implications. First, the welfare preferences of lower-income individuals – who face a relatively worse condition under inequality – should be more responsive to inequality (see also Newman, Johnston and Lown Reference Newman, Johnston and Lown2015). Secondly, lower-income individuals should be especially likely to oppose welfare for immigrants to defend their socio-economic position vis-à-vis potential competitors.

To test the implications derived from alternative theories, I investigate how the impact of inequality varies among conservative, lower-income (<20,000 euros per year) and higher-income (>40,000 euros per year) respondents.Footnote 19 If the rich are more responsive to the treatment, this would support an explanation based on altruism, while a finding that the poor are more sensitive would be evidence of self-interest. Either explanation would differ from the mechanism that I propose, based on in-group favoritism to which conservatives are more strongly predisposed.

Table 6 examines the impact of inequality conditional on respondents' conservatism.Footnote 20 Remember that, in the general sample analysis considering separate preferences (Table 3), inequality widened the gap between willingness to help natives and willingness to help immigrants by increasing support only for redistributive policies that benefit native citizens. Model 2 in Table 6 now shows that inequality also directly decreases support for immigrants' access to welfare among conservatives by 17 percentage points. The non-significance of the conservative coefficient in the control group indicates that it is exposure to inequality that activates exclusionary reactions among conservatives. In contrast inequality does not significantly decrease support for welfare for natives among the same conservative respondents (Model 1).

Table 6. Support for welfare policies for natives and immigrants among social conservatives

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

I now explore how respondents' income conditions reactions to inequality. Table 7 reveals that richer and poorer respondents exhibit similar preferences.Footnote 21 Despite the smaller sample sizes and the low statistical power, contrary to predictions based on altruism or material self-interest, the impact of inequality does not substantively vary based on respondents' income.

Table 7. Effect of inequality among lower-income and higher-income respondents

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

To examine the conditionality of the causal mechanism, I explore how income and conservatism moderate the effect of the inequality-induced belief in the lack of opportunity on welfare support. Table 8 shows that the impact of a perceived lack of opportunity is stronger among conservatives, but is not greater among lower-income citizens. Among respondents who have lost faith in the existence of economic opportunity, conservatives are more likely than non-conservatives to support welfare redistribution to natives (Model 1) and to oppose welfare support to immigrants (Model 3). On the contrary, in the subset of survey respondents who do not believe there are opportunities for social mobility, lower-income citizens are not more likely than richer citizens to support or oppose redistribution to natives vs. immigrants (Models 2 and 4). These findings provide further evidence in favor of a mechanism based on identity and in-group favoritism, rather than pure economic self-interest and competition.

Table 8. Effect of perceived lack of opportunity conditional on conservatism and income

*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001

Conclusion

Economic inequality is a serious concern in most advanced democracies. It affects social and political life in many ways, producing resentment and a weakened sense of community (Wilkinson and Pickett Reference Wilkinson and Pickett2010), decreasing social trust (Uslaner and Brown Reference Uslaner and Brown2005), and reducing civic and social participation (Alesina and La Ferrara Reference Alesina, La Ferrara and .2000).

This article shows that economic inequality also generates selective solidarity. Inequality increases support for redistribution, but only if redistributive policies benefit native-born citizens. The cross-national analysis presented here reveals a robust positive correlation in European countries between economic inequality and opposition to welfare programs that benefit immigrants. A survey experiment from Italy then isolates the causal effects. While exposure to information about inequality increases support for redistribution away from the rich and for income subsidies for native citizens, inequality does not boost individuals’ willingness to help immigrants. Among conservative citizens, inequality actually reduces support for welfare redistribution to immigrants. Inequality promotes selective solidarity by negatively affecting the belief in the existence of economic opportunities that can lead to social mobility.

These findings are consistent with prior studies showing that environments characterized by economic threats and anxiety trigger in-group favoritism (Arceneaux Reference Arceneaux2017; Carreras, Irepoglu Carreras and Bowler Reference Carreras, Irepoglu Carreras and Bowler2019; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010; Magni Reference Magni2017; Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004). Similarly, I show how inequality strengthens citizens' disposition to prioritize natives over immigrants with regard to welfare support. The macro-economic context in which individuals live, therefore, can activate identity considerations that influence policy attitudes.

My results also align with Kinder and Kam's (Reference Kinder and Kam2010) work on ethnocentrism, presented as a disposition to view the world in terms of ‘us against them’, as a generalized prejudice rather than hostility directed at specific groups. By highlighting the contrast between the rich and the rest, inequality activates in-group/out-group thinking, which then reinforces in-group favoritism and extends bias to out-groups other than the rich. Immigrants are an especially likely target, given that immigration is salient in public opinion and that political entrepreneurs often frame access to welfare services in terms of a conflict between natives and immigrants.

The fact that recipients' identity powerfully shapes the impact of inequality also helps clarify why existing comparative scholarship on preferences for redistribution – which has often focused on general redistribution – has produced inconsistent findings. My study shows that the effect of inequality is conditional on who citizens think will gain from redistribution. General measures of redistribution that do not specify who the recipients are may lead citizens to draw implicit conclusions about which groups will reap the benefits (see Gilens Reference Gilens1999; Winter Reference Winter2006). For instance, individuals for whom immigration is a more readily accessible issue may think immigrants will be the greatest beneficiaries (Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva Reference Alesina, Miano and Stantcheva2018). Explicitly taking into account recipients' identity is therefore important to precisely evaluate the impact of inequality on preferences for redistribution.

This suggests a possible re-interpretation of previous findings which showed a lack of effect of inequality on support for redistribution. In fact, inequality may spur opposing attitudes if different individuals think that different groups will benefit from redistribution. As a result, these opposing effects could cancel each other out, thereby generating what looks like a null effect at the aggregate level. Indeed, when previous studies clearly specified the target of redistributive measures, such as in the case of a real estate tax, they did find a positive effect of inequality on redistribution (Kuziemko et al. Reference Kuziemko2015).

My study also sheds further light on why the structure of inequality may affect redistribution attitudes. Previous work found that inequality favors greater support for redistribution when the middle class is closer to the bottom than the top (Lupu and Pontusson Reference Lupu and Pontusson2011). This may be due not just to the material interests of the middle class, but also to the fact that its closeness to the bottom facilitates in-group identification, which then spurs solidarity toward natives.

My findings on the effect of in-group identity also echo Larsen's (Reference Larsen2006, Reference Larsen2008), but differ on a key point. Larsen considers the divide between the rich and the poor and finds that support for redistribution is higher in social democratic welfare regimes, characterized by greater universalism and generosity, which make it easier to see everybody within the nation state as belonging to one group. Larsen, however, does not differentiate between natives and immigrants. My study, by contrast, shows that the identity divide between natives and immigrants is central under inequality. Inequality, in particular, activates in-group/out-group thinking that extends to groups other than the rich, leading to generalized in-group bias. Given the salience of immigration in the politics of welfare, immigrants are seen as a relevant out-group less deserving of support. As a result, inequality spurs selective solidarity that benefits only natives.

More broadly, my study confirms the importance of other-regarding preferences and group heterogeneity in welfare attitudes, similarly to studies that found an increased support for redistribution among the rich under inequality (Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2016; Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Dimick, Rueda and Stegmueller2018; Rueda Reference Rueda2018; Rueda and Stegmueller Reference Rueda and Stegmueller2016). My work, however, deviates from this literature on three fundamental points: the impact of inequality is not limited to the rich, is stronger among conservatives, and is mediated by a perceived lack of opportunity rather than altruism. By highlighting boundaries for solidarity between natives and immigrants, inequality strengthens in-group favoritism, rather than pure altruism.

Can we expect selective solidarity to emerge in other contexts? The experimental component of this study used Italy as a strategic case. While Italy is representative of the levels of inequality in OECD countries, beliefs in meritocratic opportunity for social mobility are especially weak in the country, which made the expectation that inequality further erodes such belies demanding. Since inequality spurs selective solidarity, one can anticipate that in countries with very low levels of inequality the division in support for natives vs. immigrants will be less profound. In contrast, countries with high levels of inequality should experience higher conditional solidarity – and, as a result, possibly greater hostility toward immigrants. These expectations are in line with findings by Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot (Reference Van Der Waal, De Koster and Van Oorschot2013), who show that individuals in liberal and conservative welfare states – where inequality tends to be higher – display more welfare chauvinism.

These effects should be amplified in countries with strong beliefs in meritocracy and social mobility. Indeed, social mobility affects satisfaction with social stratification and political trust (Daenekindt, de Koster and van der Waal Reference Daenekindt, de Koster and van der Waal2017). My findings suggest that, where these beliefs are strong, inequality has more room to negatively affect perceptions of available meritocratic opportunity, since it is not subject to floor effects as it is in Italy. Recent evidence suggests that this is happening in the United States, where inequality is increasingly sparking skepticism about meritocracy – especially among lower-income individuals (Newman, Johnston and Lown Reference Newman, Johnston and Lown2015) – and, consequently, greater support for redistribution (McCall et al. Reference McCall2017).

However, the greater ethnic and racial heterogeneity of the native population observed in many countries compared to Italy could present a challenge to selective solidarity. Perceptions of the poor as lazy, and therefore undeserving of welfare support, are higher in more ethnically divided societies (Larsen Reference Larsen2006; Larsen Reference Larsen2008). As a result, in such contexts inequality may spur support for redistribution that takes away from the rich to reduce income differences (McCall et al. Reference McCall2017) and hostility toward immigrants without increasing support for welfare policies that benefit low-income citizens. In the United States, for instance, because of the racial connotation that welfare programs have acquired in large subsets of the white electorate (Gilens Reference Gilens1999), lower-income American citizens may not display greater support for welfare programs under inequality.

The fact that selective solidarity emerges under inequality as a result of depressed beliefs in social mobility also suggests that welfare chauvinism can sometimes be a product of despair over the lack of opportunity, rather than simply a perception of scarcity based on prejudice when individuals are confronted with diversity. The distinction is important, because it identifies a societal cause for welfare chauvinism – lack of economic opportunity – rather than simply blaming individuals for their prejudices. This finding implies that promoting opportunity-enhancing policies in society could yield the important byproduct of successfully contrasting negative attitudes toward immigrants.

More broadly, this work provides a possible micro-foundational explanation for a relevant contemporary political puzzle. In times of growing inequality, why have radical right parties scored important electoral successes? Part of the answer may lie in the fact that economic inequality promotes in-group favoritism and, among favorably predisposed individuals, intensifies hostility toward immigrants. Far-right parties that often mobilize on immigration and advocate welfare chauvinism may therefore have increased their popularity by promoting nativist positions that receive greater support in times of deep economic disparity.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/INUMDT and online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000046.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Liesbet Hooghe, Gary Marks, Rahsaan Maxwell, Donald Searing, Anna Bassi, Helen Milner, Lucy Martin, Cameron Ballard-Rosa, Bilyana Petrova, Tim Ryan, Graeme Robertson, Michael MacKuen, Charlotte Cavaillé, the 2018–2019 Niehaus Center postdoctoral fellows, and the anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback. The author also received helpful feedback from the participants in the UNC comparative working group, the Princeton IR workshop, the UNC Conference on Partisan Divides in Western Societies, and the Cologne Center for Comparative Politics Workshop on Theoretical and Methodological Innovations.