The past few decades have been a period of high immigration to West European states. Since 1990, eight immigrants have arrived per year, on average, for every thousand residents. By 2017, foreign nationals comprised more than 10 per cent of their populations.Footnote 1 These demographic shifts have had a dramatic impact on European societies and economies (see, for example, Geddes and Scholten Reference Geddes and Scholten2016). They have also had powerful and controversial effects on public opinion and political behavior. Many scholars argue that high levels of immigration create a public backlash (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2017; Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2014; Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019; Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002; Strabac and Listhaug Reference Strabac and Listhaug2008) due to the economic and cultural threats it poses for native citizens. One needs to look no further than the rise of anti-immigrant, radical right parties for apparent evidence of this effect (for example, Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2008; Lucassen and Lubbers Reference Lucassen and Lubbers2012; Norris Reference Norris2005; Rydgren Reference Rydgren2008).

Yet countervailing forces might lead natives to support immigration even when immigration rates are high. These include immediate contact between natives and immigrants (for example, McLaren Reference McLaren2003; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner2003), the potential economic gains from immigration (for example, Dancygier and Donnelly Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2013) and socialization in multicultural societies (for example, Bloemraad and Wright Reference Bloemraad and Wright2014). Whatever the mechanism, evidence of such habituation effects can also be readily found. Support for immigration in countries like Germany and the United Kingdom is at historically high levels (as we demonstrate below), and major European metropolitan areas are now both diverse in demography and cosmopolitan in orientation (Maxwell Reference Maxwell2019). Indeed, some studies find that immigration raises public support (Van Hauwaert and English Reference Van Hauwaert and English2019).

This article tests these competing theories of public backlash and habituation in response to mass immigration. We examine whether higher inflows of immigrants produce lower public support and greater public concern about immigration, or whether these inflows lead to higher support and less concern. There is now considerable research on the link between immigrant numbers and immigration opinion (for example, Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010; Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2014; Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet Reference Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet2009; Quillian Reference Quillian1995; Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002; Strabac and Listhaug Reference Strabac and Listhaug2008).

However, four obstacles have prevented researchers from reaching definitive conclusions. First, in contrast to their static treatment in prior research, backlash and habituation are dynamic processes: their effects unfold over time (perhaps at different rates). Secondly, many previous studies are cross-sectional in design; they are unable to separate the effects of immigration on subsequent opinion from the reverse effects of opinion on subsequent flows of immigration (for example, via political pressure and policy changes). Thirdly, cross-sectional designs cannot adequately deal with possible country-specific confounds, such as national experiences with immigration that date back to at least the mid-twentieth century (for example, Castles, de Haas and Miller Reference Castles, de Haas and Miller2014; Hiers, Soehl and Wimmer Reference Hiers, Soehl and Wimmer2017). Finally, there are two quite distinct forms of immigration opinion that must be considered: (1) positive or negative perceptions of, or orientations to, immigration and (2) the relative salience of the issue (Dennison and Geddes Reference Dennison and Geddes2019; Jennings Reference Jennings2009). Existing research has focused exclusively on one or the other.

To address these obstacles, we produce two new time-series, cross-sectional (TSCS) measures of national immigration opinion by combining up to 29 years' worth of fractured public opinion items using a dynamic Bayesian latent variable model (Claassen Reference Claassen2019). To measure national immigration mood, we combine survey data on immigration perceptions from 808 nationally representative public opinion surveys fielded in forty-three European countries (plus Turkey) from as early as 1988 to 2017. We also measure national immigration concern by integrating various survey measures of the salience of immigration as a political issue from 469 nationally representative public opinion surveys fielded in thirty-four European countries between 2002 and 2018. These two new measures allow us to tackle all four obstacles that have hindered understanding of the link between immigration inflows and immigration opinion, thereby providing definitive tests of the backlash and habituation hypotheses.

Using dynamic fixed effects models and simulations, we find evidence that immigration exerts both backlash and habituation effects on national immigration opinion. Increases in immigration rates lead to backlashes in European public opinion, which increases concerns about immigration and produces a more hostile immigration mood. However, these backlash effects are less pronounced if more immigrants already reside in a country. They also fade over time as publics become habituated to immigration.

Our findings will be of interest to other scholars studying the effects of immigration and diversity on immigration opinions, and to policy makers concerned with this relationship. Our findings also have wider implications, particularly for research on the impact of diversity on social capital. Social capital – for example, interpersonal trust and participation in communities – is thought to be a crucial societal resource that ensures the effective functioning of democracy and contributes to economic development, as well as physical and mental health (and has many other benefits). Rather ominously, seminal research by Alesina and Ferrara (Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2000, Alesina and Ferrara Reference Alesina and La Ferrara2002) and Putnam (Reference Putnam2007) suggested that increased diversity could exert powerful negative effects on this vital resource. This has prompted a vast interdisciplinary literature – with results that are similarly mixed to those found in the immigration numbers-opinion literature (see the review and meta-analysis by van der Meer and Tolsma Reference van der Meer and Tolsma2014). However, this body of research suffers from similar shortcomings as those found in the immigration numbers-opinion literature: limited consideration of both short- and longer-term effects of diversity while simultaneously incorporating country contexts. Our findings suggest that – at least in the European context – any apparent negative effects of immigration-related diversity on social capital may be short-lived, and that at the very least, short- and long-term effects must both be considered.

Backlash and Habituation in The Existing Literature

The question of whether immigrant numbers are linked to public hostility to immigrants and immigration has been the focus of academic research since the advent of cross-national survey measures of attitudes to immigrants and immigration in the late 1980s. Backlash theories have largely dominated this area of research. These theories have drawn on the concepts of economic and symbolic threat developed by scholars of racial prejudice in the United States (for example, Blumer Reference Blumer1958) to argue that the larger the population of immigrants, the greater the hostility from the native population and the stronger their preference for more restrictive immigration policies.

In the European context, since the work of Quillian (Reference Quillian1995), scholars have tended to investigate these backlash theories using multilevel, cross-sectional research designs, with thousands of survey respondents nested within 12–30 European societies. They have generally found that – as predicted by backlash theories – larger populations of immigrants are associated with greater animosity (Quillian Reference Quillian1995; Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders Reference Scheepers, Gijsberts and Coenders2002; Strabac and Listhaug Reference Strabac and Listhaug2008). A key assumption in this literature is that increases in immigration will continue to produce anti-immigration hostility over the long term due to the continued pressure of economic and cultural threats. We use our longitudinal (and cross-sectional) data to test the backlash hypothesis, in both the short and longer term.

Hypothesis 1 Higher immigration inflows are associated with more negative immigration mood and an increase in concern about immigration.

However, even if backlash effects are evident in the short run, we might expect them to diminish in the longer run for three reasons. First, although there is some evidence of the backlash effect (as described above), there is also a growing body of contradictory evidence. In some cases, there appears to be no relationship between immigrant numbers and immigration opinion (Evans and Need Reference Evans and Need2002). In other cases, a positive relationship is evident – that is, higher immigrant numbers coincide with more positive immigration opinions, which directly counters the backlash hypothesis (Sides and Citrin Reference Sides and Citrin2007; Van Hauwaert and English Reference Van Hauwaert and English2019). These findings point to the possibility that the backlash effects found in earlier research may now be changing drastically as European countries adapt to being destinations for migrants. This may be due, for example, to the economic gains from immigration (Dancygier and Donnelly Reference Dancygier and Donnelly2013) or the habituating influences of multiculturalist policies (Bloemraad and Wright Reference Bloemraad and Wright2014).

Secondly, there is persistent evidence of micro-level contact effects (Hewstone and Swart Reference Hewstone and Swart2011; Stein, Post, and Rinden Reference Stein, Post and Rinden2000; Wagner et al. Reference Wagner2003; Weber Reference Weber2019). Contact with immigrant-origin minorities, especially in the form of friendships, produces more positive attitudes to these groups. As domestic populations gain increased opportunities for this type of contact, it might be expected that, with the passage of time, immigrants and immigration will become a more accepted part of society.Footnote 2

Thirdly, a small body of scholarly work contends that, over time, societies appear to become habituated to, and more accepting of, groups of immigrants who migrated decades previously. For instance, even in the short time span between 1983 and 1996, Ford (Reference Ford2011) shows that the British population became more accepting of earlier-arriving groups of immigrants, such as from the West Indies and South Asia (see also Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2014). Recent work by Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2018; discussed further below) also suggests the potential for habituation.

In short, immigration numbers and public opinion likely have a complex, interactive relationship that unfolds over time: numbers at one point in time may trigger subsequent public opposition, which then leads to an immigration clampdown and reduced numbers at some future point in time (for example, Jennings Reference Jennings2009). With only one time point, cross-sectional designs cannot begin to address such complexities. While some studies do examine data on immigration numbers and opinions, which includes a longitudinal aspect (for example, Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2014; Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet Reference Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet2009; Semyonov, Raijman and Gorodzeisky Reference Semyonov, Raijman and Gorodzeisky2006; Van Hauwaert and English Reference Van Hauwaert and English2019), the authors do not use dynamic models to examine these data, and thereby miss an opportunity to gain leverage on this issue. In the short term, immigration may have a backlash effect that increases public opposition (Coenders and Scheepers Reference Coenders and Scheepers2008; Duffy Reference Duffy2014; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010; Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2014; Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet Reference Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet2009), while in the long term, a habituation effect that reduces public antipathy may come into play (Stein, Post and Rinden Reference Stein, Post and Rinden2000; Van Hauwaert and English Reference Van Hauwaert and English2019). Our second hypothesis is therefore:

Hypothesis 2 Higher immigration inflows are associated with less negative immigration mood and reduced concern about immigration in the long run.

The ‘long run’ is admittedly a fairly imprecise concept. Yet the lack of research on the long-term effects of immigration on public opinion makes greater precision difficult. Nevertheless, some research from the UK suggests that habituation to new immigration-origin diversity may occur within a decade (Ford Reference Ford2011; Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2014). Our analyses allow us to investigate this possibility cross-nationally and to produce more precise estimates of when, if at all, a habituation effect becomes visible.

The Importance of The Dynamic National Immigration Context

Cross-national differences in post-WWII migration to Europe are also relevant to understanding how European publics react to new immigration. In countries like Austria, Belgium, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK, immigrant labor was seen as crucial to early post-war development (Castles, de Haas, and Miller Reference Castles, de Haas and Miller2014). Though the expectation in Austria, Germany and Switzerland was that ‘guestworkers’ would return home, by the 1980s this expectation bore little resemblance to reality. By the 1990s approximately 10 per cent of the population in these three countries (as well as Belgium, Sweden and the UK) was estimated to be of foreign origin.Footnote 3

Countries like Spain, Ireland and Norway provide an illuminating contrast. Here, levels of immigration were relatively low even by the late 1990s: in 1998, the percentage of residents of each country who were not citizens was 1.6, 2.8 and 3.6 per cent, respectively. Yet 20 years later, these countries had among the highest immigrant numbers in Europe: 9.8 per cent of residents of Spain in 2018 were not citizens, 12.2 per cent of Irish residents and 10.7 per cent in Norway. In Eastern Europe, the situation is different still. For example, in Hungary and Slovakia low proportions of non-citizens (1.4 and 0.5 per cent, respectively) in 1998 had risen only slightly by 2018 (to 1.7 and 1.3 per cent).

These represent significant differences in the history of, and experience with, immigration at any given point in time. In countries like Austria, Belgium, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland and the UK, newcomers arriving at the turn of this century would be introduced to contexts in which there were already substantial, well-established immigrant-origin minorities and where non-immigrant-origin domestic populations are likely to have become more habituated to the presence of these minorities compared to the newer countries of immigration. In such contexts, increases or decreases in the number of newcomers may not have much impact on public mood regarding immigration. Even if media reports on immigration are rising (or falling) in these countries in response to fluctuations in numbers, this does not necessarily result in a more negative public mood (see Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Reference Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2009 for the case of Germany). In effect, increases in immigrant-origin minorities are hardly likely to be noticed, and even media-reported numbers are likely to be competing with other factors such as personal contact experience and socialization in determining how individuals perceive immigration.

Indeed, a recent analysis of 2002–2014 European Social Survey data by Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2018) suggests a differential impact of influxes of immigration: in countries that are newer immigration destinations, increased immigration levels produce significant rises in anti-immigrant hostility, but in countries that have long received immigrants, new immigration ‘hardly exerts any effect on anti-immigrant attitudes’ (40). Their findings also suggest that while some birth cohorts are impacted more heavily by a sudden switch to becoming a country of immigration, adaptation occurs in subsequent cohorts. Findings from a cross-sectional analysis of British immigration opinion similarly indicate that ‘whites in more diverse wards are more tolerant of immigration’ (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2014, 270), which leads the author to contend that the domestic population is very likely to habituate to immigrant-origin diversity over a relatively short period of time. These findings imply that in places and times when immigration and immigrant-origin minorities were not overly prominent – for example, Southern Europe, Ireland, and Central and East European countries in the late 1980s/early 1990s – sudden large numbers of newcomers are likely to prompt a backlash.

The habituation perspective therefore implies an interactive effect between the size of the existing immigrant-origin population and the number of new migrants entering the country at a given time. To the best of our knowledge, until now it has been impossible to systematically investigate this habituation hypothesis due to limited cross-time immigration opinion data. The hypotheses we test are:

Hypothesis 3a The existing number of immigrants moderates the effects of immigrant inflows on immigration mood, that is, any decrease in mood following an increase in immigration will be moderated by the number of migrants already in the country at the time.

Hypothesis 3b The existing number of immigrants moderates the effects of immigrant inflows on immigration concern, that is, any increase in concern following an increase in immigration will be moderated by the number of migrants already in the country at the time.

Measuring Immigration Mood

Immigration mood measures the extent to which national European publics regard immigrants favorably, immigration as desirable, and prefer a relatively more open immigration policy.Footnote 4 It captures general preferences regarding the overall direction of immigration policy as well as more specific beliefs regarding the social benefits and costs of immigration. It does not measure attitudes towards ethnic or religious outgroups per se. (See the Appendix for further details regarding the specific survey items.)

Existing survey measures of immigration mood are fragmented across numerous public opinion projects, and often use very different survey questions and suffer from sporadic coverage over time. There have been several attempts to unite such disparate cross-national opinion data in a coherent fashion. For example, Van Hauwaert and English (Reference Van Hauwaert and English2019) use Stimson's dyadic ratios algorithm to create longitudinal measures of immigration mood in the subnational regions of three European countries. Jennings (Reference Jennings2009) employs the same method to estimate a mood time series in a single country, the UK. Closer to our ambitions is the ‘immigration ideology’ measure developed by Caughey, O'Grady and Warshaw (Reference Caughey, O'Grady and Warshaw2019), which covers most European countries from 1990 to 2015. However, this measure does not account for the cross-national nature of the underlying survey data as it relies on the model of Caughey and Warshaw (Reference Caughey and Warshaw2015), which is designed for estimating subnational rather than cross-national panels of opinion. We therefore created a new measure of immigration mood using Claassen's (Reference Claassen2019) dynamic Bayesian latent variable model, which is developed specifically for cross-national opinion data and is more accurate in such contexts.Footnote 5

We collected a dataset of 4,030 nationally aggregated survey measures of immigration mood, from forty-five countries in Europe and its periphery (for example, Russia and Turkey). These survey responses were gathered by six survey projects: the Eurobarometer, European Social Survey, European Values Study, World Values Survey, Pew Global Attitudes Survey and the International Social Survey Programme. In total, our data were gathered by 812 nationally representative surveys using as many as forty-four different survey items, and constitute the aggregate opinions of more than a million people.

After dropping countries that were surveyed less than three times, we have data for forty-three countries and up to twenty-nine years (between 1988 and 2017).Footnote 6 We dropped a further thirteen, mostly Eastern European, countries from our dataset because of short opinion time series and a lack of data on immigration flows.Footnote 7 We are left with thirty cases. In addition to all West European states, our sample includes the Eastern European states of Croatia, Czechia, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Romania, Slovakia and Slovenia, which have begun receiving heightened flows of immigrants in recent years, making them particularly useful for understanding the effects of new immigration when immigrant numbers are relatively low.Footnote 8 The dynamic Bayesian latent variable model was then applied to this dataset to estimate national mood.

Figure 1 shows the cross-national trends in immigration mood. Among the countries that have had longer experience with high immigration numbers and relatively large immigrant-origin populations, immigration mood tends to be more positive, on average, compared to most of the countries with smaller immigrant-origin populations. In many of the former group of countries, immigration mood is relatively positive in the late 1980s before dipping in the early 1990s (for example, Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, Luxembourg and Netherlands). For most of these countries, however, there was a gradual movement towards a more positive mood around the late 1990s, with some fluctuation. Our data for Austria and Switzerland are more limited, but there appears to be slight movement towards a more positive mood in both countries after the late 1990s, though with a turn toward a more negative mood again by 2017 in Switzerland. Like many of the more experienced countries of immigration, the UK appears to experience a similar drop in immigration mood in the early part of our series, but unlike the other countries that have a long history of immigration, immigration mood only started to become more positive after around 2010.

Figure 1. National time-serial estimates of immigration mood and concern

Note: these plots show the national time-serial estimates of immigration mood and immigration concern. Both are standardized to have a mean of 0 and variance of 1. Higher levels of immigration mood indicate the extent to which publics regard immigrants favorably, immigration as desirable, and prefer a relatively more open immigration policy. Higher levels of immigration concern indicate greater concern about the issue of immigration relative to all other issues.

These trends can be contrasted with those in many of the Central and Eastern European countries, where immigration has been relatively low until recently. For instance, in Czechia, Hungary, Latvia and Slovakia, immigration mood is generally relatively negative, and became even more so around the time of the 2015 refugee crisis. In Poland, immigration mood was relatively neutral in the late 1990s, became more positive between 2005–2010, followed by a gradual decline again in 2015. In Romania, Lithuania and Slovenia, immigration mood also started as relatively negative but became more positive (with fluctuation) – again, with some turn towards a negative mood around the time of the 2015 refugee crisis.

The publics of Southern Europe, Ireland and the Nordic countries are all generally more positive about immigration than other countries (again, on average) – apart from Greece and Italy, where immigration mood has become increasingly negative over time (with some fluctuation). As with countries that have more extensive experience with post-war migration, the mood in Southern Europe and Ireland became more negative in the early 1990s before shifting towards a significantly more positive direction. Similar patterns can be found in the Nordic countries (apart from Denmark, discussed above).

The patterns in immigration mood described above are largely consistent with existing cross-national research on immigration opinions. For example, our estimates of immigration mood in Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, Luxembourg and the Netherlands echo the findings of Semyonov, Raijman and Gorodzeisky (Reference Semyonov, Raijman and Gorodzeisky2006) regarding an increase in ethnic prejudice between 1988 and 1992, as well as those of Coenders and Scheepers (Reference Coenders and Scheepers1998) that show a rise in support for ethnic discrimination in the Netherlands in the mid-1990s. The wider European analyses of Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet (Reference Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet2009) and Bohman and Hjerm (Reference Bohman and Hjerm2016), covering the 2002–2007 and 2002–2012 periods, respectively, find that the most negative attitudes to immigration were in Austria, Hungary, Poland and Portugal (although Bohman and Hjerm's analyses show more positive attitudes in Poland in 2006–2012); the most positive attitudes in these two studies were found in Sweden, Switzerland, Denmark and Norway, which is also consistent with our estimates. Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet (Reference Meuleman, Davidov and Billiet2009) further note that it was Southern and Eastern European countries, that is, those that had started to experience sizable immigration at the start of their study period, that exhibited the lowest support for immigration in the 2002–2007 period. Some of the findings in Bohman and Hjerm (Reference Bohman and Hjerm2016) are similar, with especially high levels of anti-immigration attitudes in Portugal and high levels of nativist opposition to immigration in both Portugal and Spain for the 2002–2012 period. Our results over the same period are consistent. Finally, the trends in anti-immigrant sentiment from 2002 to 2014 depicted in Gorodzeisky and Semyonov (Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2018) mirror those shown here, with anti-immigrant attitudes relatively high in Austria, Belgium, France, Great Britain and Portugal, and relatively low in Denmark, Finland, Sweden and Switzerland for their period of study (see also Bohman and Hjerm Reference Bohman and Hjerm2016).

Measuring Immigration Concern

Immigration concern measures the importance that national publics place on immigration relative to other political issues. Immigration concern rises when immigration moves onto the agenda, and falls when other issues become more pressing in the public eye. Thus while immigration mood captures the general orientation to immigrants and immigration, concern captures the degree to which these public preferences are likely to produce pressure on political actors (for example, Dennison and Geddes Reference Dennison and Geddes2019).

Since the Eurobarometer has measured immigration concern annually, there are fewer hurdles in assembling a TSCS dataset of concern than there are in constructing a TSCS dataset of immigration mood. (See Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio Reference Böhmelt, Bove and Nussio2020 for a recent example of the former.) Yet since the Eurobarometer has adjusted the response set for its ‘most important issue’ question several times, there are still benefits in applying Claassen's (Reference Claassen2019) dynamic latent variable model. Specifically, the model allows us to estimate – and separate out – the item bias that results from such changes in response sets. It further allows this item bias to vary by country, capturing any cross-national error caused by a lack of equivalence of items across countries. We therefore estimated immigration concern using our latent variable model applied to all the nationally aggregated Eurobarometer measures of immigration as the most important political issue. Data are available for thirty-four countries and sixteen years (ranging from 2002 until 2017) and are collected by 931 nationally representative Eurobarometer surveys. The response set changed twice during the period, in 2006 and again in 2012; we treat the three response sets as separate items. After integrating our concern estimates with our mood estimates, twenty-eight countries remain; the non-EU states of Norway and Switzerland are the two cases with estimates of mood but not concern.

Figure 1 illustrates the cross-national, cross-time differences in immigration concern. The fluctuations emphasize the importance of considering both mood and concern. In some countries, the two indicators appear to track each other fairly closely, but in the opposite direction to what might be expected (for example, Belgium, Croatia, Cyprus and possibly Germany, Ireland and Sweden to some extent). That is, a more positive mood appears to be associated with greater concern about immigration. In other countries (for example, Czechia, Estonia, Greece, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Spain and the UK), a rise in concern appears to be associated with more negative mood, as is often assumed in analyses that use the former to measure the latter (for example, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Reference Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2009; McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart Reference McLaren, Boomgaarden and Vliegenthart2018). However, in many other countries, fluctuations in these two opinion series diverge. It is therefore not clear that the public are responding to similar factors (such as immigration levels) across the two indicators.

Measuring Immigration Flows

We employ two main measures of migration flows. The first is immigration inflows, the number of immigrants arriving in a given country each year as a percentage of the receiving-country population. The second measure is net migration, the number of arrivals less the number of people (immigrants and citizens) departing each year, again measured as a percentage of the receiving-country population. There are subtle differences in interpretation. While immigration inflows focus only on immigration, net migration also factors in the emigration of citizens, therefore measuring the change in population that is due to migration flows in both directions.Footnote 9 Data for immigration inflows and net migration are drawn from three sources: the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Eurostat, and the Determinants of International Migration (DEMIG) project.Footnote 10 There was substantial overlap in these datasets: many of the estimates were identical for particular country-years. Multilevel linear models with country-varying intercepts and slopes were used to combine these data where there were missing values in one or two of the sources.Footnote 11

To measure stocks of residents with an immigrant background, we use a measure of the percent of each national population who were not citizens in a given year. Data were obtained from the OECD and Eurostat and were combined using multilevel linear models. Linear interpolation was used to interpolate missing values in one national case (France).

Empirical Strategy

What is the best way to model the effects of immigration on public opinion? Since the backlash effect may depend on the existing stock of immigrants (that is, as spelled out in Hypotheses 3a and 3b above), we allow stocks to moderate the effects of flows – that is, we specify an interaction term between these variables. In a departure from previous analyses, we examine the effects of flows (as moderated by stocks) on two dependent variables: Immigration Mood and Concern about Immigration. We also use a fully TSCS design that includes lagged dependent variables, lags and first differences of immigration inflows, and country fixed effects. These features allow us to: model both the short- and long-run effects of immigration; tackle the possibility of reverse causation; and deal with the potential existence of country-specific confounding factors. (We discuss each of these features in more detail in the Appendix). The model is as follows (for i countries, t years and k control variables, where s is immigrant stock and f is immigration flows):

$$y_{it} = \phi _1y_{it-1} + \phi _2y_{it-2} + \beta _1f_{it-1} + \beta _2\Delta f_{it} + \beta _3s_{it-1} + \beta _4f_{it-1}s_{it-1} + \beta _5\Delta f_{it}s_{it-1} + \mathop \sum \limits_{k = 1}^K \gamma _kx_{kit-1} + \upsilon _i + {\epsilon}_{it}$$

$$y_{it} = \phi _1y_{it-1} + \phi _2y_{it-2} + \beta _1f_{it-1} + \beta _2\Delta f_{it} + \beta _3s_{it-1} + \beta _4f_{it-1}s_{it-1} + \beta _5\Delta f_{it}s_{it-1} + \mathop \sum \limits_{k = 1}^K \gamma _kx_{kit-1} + \upsilon _i + {\epsilon}_{it}$$With country fixed effects υi removing the influence of all time-invariant, country-varying factors, we include a set of control variables x kit that vary across countries and over time and plausibly affect immigration inflows and immigration opinion. First, periods of economic expansion likely attract more immigrants but also lead to less restrictive immigration attitudes (Gorodzeisky and Semyonov Reference Gorodzeisky and Semyonov2016). We include Growth in GDP Per Capita and the National Unemployment rate to control for such processes. Secondly, far-right parties may prompt greater anti-immigration hostility and concern by legitimizing anti-immigration attitudes and signaling that immigration is an important issue (Bohman and Hjerm Reference Bohman and Hjerm2016). We therefore include the Percent of Seats Held by Far-right Parties in the year in question (we use the PopuList 2.0 definition of far-right parties (Rooduijn et al. Reference Rooduijn2019), and link this to parties' seat shares from ParlGov (Döring and Manow Reference Döring and Manow2019). We further include two time-varying measures of immigration policy that capture the restrictiveness of Immigration Entry Policy and Immigrant Integration Policy. Both are estimated by Rayp, Ruyssen and Standaert (Reference Rayp, Ruyssen and Standaert2017) using a Bayesian latent variable model applied to existing immigration policy measures (such as MPI, MIPEX).

Our model posits rather complex effects of migration flows on public opinion, which depend on existing stocks of immigrants, unfold over time and may change future stocks of immigrants. In addition to reporting the direct parameter estimates of this model, we also use simulations to show how the effects unfold and accumulate (or dissipate) over time. These simulations follow the method laid out by Williams and Whitten (Reference Williams and Whitten2012) for simulating long-run effects from TSCS models. We begin by setting all independent variables to zero (which is the country mean given the use of fixed effects); the non-citizen stock variable is set at a low level (−5). These values are plugged into each model to produce predicted effects of opinion change in the next period. Allowing for these predicted effects to feed into the next period's equation via the lagged dependent variable, this system of equations is run for 100 years. To examine the effects of a rise in immigration, we then increase the relevant variable (that is, Immigration Inflows or Net Migration) by one standard deviation and allow the equations to run for 30 more years (again ensuring that the predicted effects feed forward to the subsequent periods via the lagged dependent variables). Given that increases in immigration mechanically produce increases in the stock of non-citizens, we further allow the latter to rise each year based on estimates obtained from a simple dynamic demographic model (see the Appendix for the results of this model). To incorporate uncertainty, we repeat this method 10,000 times. Each iteration is based on an independent draw from a multivariate normal distribution; the expectation is that the vector of model coefficients and variance will be the robust covariance matrix. We therefore include only the uncertainty associated with the model coefficients, which is appropriate for the in-sample counterfactual prediction we make here. Because we are also forecasting future values of demographics based on current values of immigration change, we additionally include the out-of-sample uncertainty for these demographic models. Specifically, we add uncertainty based on the regression standard error for the demographic model.

Findings

Immigration Mood

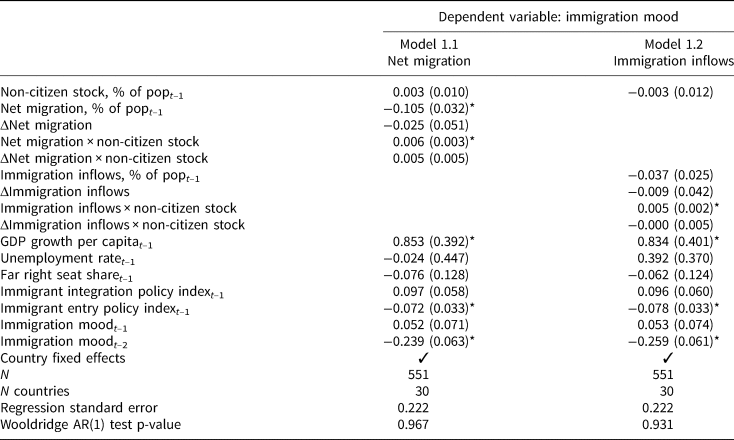

We begin our discussion of the results by focusing on immigration mood. Table 1 shows the results of our dynamic fixed effects models of annual changes in immigration mood. Both models include lagged and first-differenced measures of migration flows. The former captures any enduring effects of migration flows; the latter, any immediate, transient effects. We allow the coefficients of both to vary according to the size of the immigrant community to test the backlash versus habituation theories. The two models vary only in the measure of migration flows that are included: Model 1.1 uses net migration, while Model 1.2 uses immigration inflows.

Table 1. Drivers of change in public immigration mood

Note: coefficient estimates from dynamic fixed effects models with Driscoll-Kraay robust standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is the annual change in national immigration mood. *p < 0.05

The results in Table 1 demonstrate that there are no significant effects of the first-differenced measures of either net migration or immigration inflows, suggesting that migration flows have no negative effect on immigration mood. The longer-run effects of migration flows on subsequent immigration mood then depend somewhat on which measure is used. Lagged net migration shows a negative and significant coefficient (Model 1.1), indicating a potentially substantial long-run backlash effect. The effect of lagged immigration inflows is also negative, but insignificant (Model 1.2). We therefore find mixed support for the standard threat hypothesis outlined above (Hypothesis 1), that is, that higher immigration numbers will be associated with subsequently more negative immigration opinions. However, both of these lagged measures of migration flows show positive interaction effects with existing immigrant stocks. This indicates that any long-run negative effects of immigration on mood should diminish as the number of immigrants increases, which is consistent with Hypothesis 3a.

To unpack these rather complex effects, we turn to our dynamic simulations (Figure 2). (In the Appendix, we also include and discuss the static marginal effects of migration flows by immigrant stock interaction.) These simulations show how the short-run effects of migration flows (reported in Table 1) accumulate over time. They also factor in the effects of long-run migration inflows on the total stock of immigrants in each society. The top row shows the long-run effects when immigrant stocks begin at a very low level (5 percentage points below the country average). The bottom row shows the long-run effects when the stock of immigrants begins at each country's average level. Both sets of simulations explicitly model the impact of immigration on the current stock of immigrants. The magnitude of this effect is, unsurprisingly, very large.Footnote 12 This allows immigration to shape opinion through both a direct channel, as shown in the results in Table 1, as well as an indirect channel, by increasing the stock of immigrants. Stock then creates a more positive immigration mood through the ameliorating effects of the flows by stock interaction terms, which are positive and significant in both Models 1.1 and 1.2. This total effect of immigrant stock is more pronounced when we measure migration flows using net migration because the main effect of immigrant stock is also positive in this model (Model 1.1), albeit insignificantly so.

Figure 2. Simulated effects of changes in net migration and immigration flows on long-run changes in immigration mood

Note: the plots show the simulated within-sample effects of permanent, within-country, two-standard-deviation increases in net migration (±0.8 percentage points; left plots) and immigration flows (±0.6 percentage points; right plots) when existing immigration stocks are either low (top row; five percentage points below the country average) or average (bottom row; country average). These simulations rely on parameter and variance–covariance estimates obtained from the dynamic fixed effects models reported in Table 1, but also include the predicted effects of net migration on immigrant stock, using parameter estimates and model uncertainty obtained from a dedicated model of immigrant stock accumulation. The solid lines indicate the mean simulated effect; the shaded regions indicate the 95 per cent confidence intervals of these effects.

As can be seen in Figure 2, when we model both the direct and indirect effects of immigration, the negative effect of an increase in the rate of net migration on mood is somewhat transient. When existing immigrant stocks are low (top row), an initial backlash is followed by a habituation effect that ultimately restores mood. Some 20–30 years after the initial increase, opinion returns to baseline levels. The backlash effect is estimated to be much weaker when we use immigration inflows as the measure of migration flow, which is consistent with the smaller and insignificant effect reported in Table 1.

In sum, when we model both the direct and indirect long-run effects of immigration, we find evidence to support both the backlash and habituation theories. The question remains whether immigration concern, the other major form of immigration opinion, responds to immigration flows in a backlash-followed-by-habituation fashion, or whether it follows a different logic entirely.

Immigration Concern

Table 2 reports the results of dynamic fixed effects models of immigration concern. These models are specified exactly as the corresponding models of immigration mood were. Model 2.1 uses net migration to measure migration flows; Model 2.2. uses immigration inflows.

Table 2. Drivers of change in public immigration concern

Note: coefficient estimates from dynamic fixed effects models with Driscoll-Kraay robust standard errors in parentheses. The dependent variable is the annual change in national immigration concern. *p < 0.05

On the face of it, the results appear to be quite different to those obtained for immigration mood. The lag of migration inflows is insignificant in both models (although fairly large in magnitude for net migration). Nor is there a significant or even substantial interaction effect. A positive effect of the change in the rate of immigration inflows is apparent in Model 2.2, which indicates an immediate backlash effect of increases in immigration inflows; however, the corresponding effect is smaller and insignificant in Model 2.1.Footnote 13

With interaction terms and lagged dependent variables included in these models, as well as the indirect effects of immigration on higher immigrant stocks to factor in, it should be more insightful to examine the long-run simulated effects, which are displayed in Figure 3. These simulated effects again include the predicted effects of migration flows on immigrant stocks. The top row of plots shows the effects of immigration on concern when the existing level of immigrant stocks is low, and the bottom row reports these effects when stocks are at country averages. In a pattern that we saw previously in Figure 2, an increase in migration flows produces both a backlash effect (that is, increased concern) in the short term and a habituation effect (decreased concern) in the medium to long term. The shift in opinion is even more dramatic for concern than it was for mood. The net migration model suggests that a steep rise in concern occurs a few years after an increase in immigration. This subsequently fades in a similarly rapid fashion, with opinion returning to baseline levels within a decade. The immigration inflows model implies a briefer and less pronounced backlash effect. But it implies a stronger and more rapidly manifesting habituation effect in which, a decade after a large increase in immigration, public concern is expected to drop below the baseline level and continue to fall over the ensuing years as immigrants become more established in that society.

Figure 3. Simulated effects of changes in net migration and immigration flows on long-run changes in immigration concern

Note: the plots show the simulated within-sample effects of permanent, within-country, two standard deviation increases in net migration (±0.8 percentage points; left plots) and immigration flows (±0.6 percentage points; right plots) when existing immigration stocks are either low (top row; 5 percentage points below the country average) or average (bottom row; country average). These simulations rely on parameter and variance-covariance estimates obtained from the dynamic fixed effects models reported in Table 2, but also include the predicted effects of net migration on immigrant stock, using parameter estimates and model uncertainty obtained from a dedicated model of immigrant stock accumulation. The solid lines indicate the mean simulated effect; the shaded regions indicate the 95 per cent confidence intervals of these effects.

Once again, both the backlash and habituation effects are dampened when we consider a situation in which the average levels of existing immigrant stock are coupled with increasing rates of immigration. These results (bottom row) show a weaker backlash effect when there is an increase in net migration, and no backlash effect at all following an increase in immigration inflows.

In sum, immigration turns out to have broadly similar effects on both immigration mood and immigration concern. These effects are generally consistent across the two measures of migration flows we have examined, net migration and immigration inflows. To further test the robustness of our results, we employ four additional specifications: (1) including two-way fixed effects, (2) limiting the sample to Western Europe, (3) using immigration inflows from Muslim-majority countries as the measure of migration flows and (4) estimating immigration mood using only respondents who identify as citizens or nationals of their countries of residence. The results (available in the Appendix) are largely similar to those reported above. Across these various measures and models, we find evidence of a public backlash in the short to medium run, in which mood turns negative, and concern with immigration rises. There is also evidence, however, that the public becomes habituated to more immigrants and higher rates of immigration: the backlash effect reverses within one (concern) to three (mood) decades. These effects are particularly pronounced in situations where immigrants are few; where the stock of immigrants is higher, the backlash effect is reduced.

Conclusion

This article analyzes one of the most important questions currently facing Western democracies: what are the likely consequences of continued migration for public opinion and the broader political landscapes in these countries? Will immigration continue to be a source of major division within these societies, for instance? Or is it possible that Western societies are adapting to, and perhaps even embracing, modern large-scale immigration?

Our ability to answer such questions has been limited by a lack of cross-time and cross-national public opinion data, and by a focus on only one of the two major forms of immigration opinion: concern (that is, salience) or mood (the positive and negative aspects of immigration and/or preferred immigration levels). Our TSCS measures of both immigration concern and immigration mood allow us to address the issues that have hindered research on this question: that immigration inflows likely have enduring, long-run effects on opinion; that opinion is as likely to affect future numbers as numbers are to affect future opinion; and that time-invariant historical, cultural and institutional factors likely confound any observed cross-sectional relationship between numbers and opinions.

We find evidence of both the more pessimistic backlash as well as the more optimistic habituation theories. In places and at times when there are relatively few immigrants already in the country, there is some evidence that the short-term public reaction to new immigration is negative – whether expressed as a growing disapproval of immigration or as a heightened concern about it as a political issue. Yet as a country develops more extensive experience with immigration, citizens appear to become habituated to the existence of immigrant-origin minorities and the short-term backlash recedes and becomes insignificant, even if inflows of immigrants remain high. The implication, therefore, is that – in time – immigration may no longer be the major source of contention that it currently is in many countries.

Our findings make a significant contribution to a body of research that has struggled to understand whether mass publics react negatively to growing numbers (and percentages) of immigrant-origin minorities or not. We have argued that any definitive answer to this question requires a dynamic approach that can incorporate both short- and long-term responses as well as cross-national historical contexts.

The article's findings are relevant not only to research on immigration attitudes, but also to research on social capital and cohesion, which has struggled to definitively address the widely publicized concern raised by Robert Putnam (Reference Putnam2007) that diversity appears to undermine social capital and cohesion (also see van der Meer and Tolsma Reference van der Meer and Tolsma2014). Our findings suggest that the relationship between diversity and cohesion requires dynamic modeling to understand both the short- and long-term effects of diversity and that if mass publics do indeed adapt to it, Putnam's pessimistic conclusions may only apply in the short term.

Our data and findings present several avenues for future research. First and foremost, it will be important to continue to monitor the dynamic relationships we have identified in this article by extending the immigration opinion series as future public opinion data become available. The long-term habituation we have identified implies that immigration opinions (especially concern about immigration) may become increasingly supportive of immigration over time, but data will be required to investigate this possibility. Future research should also analyze the extent to which becoming countries of immigration in places like Czechia, Hungary and Romania changes public mood toward immigration and immigrants, as would be predicted from this article's findings, or whether the anti-immigration rhetoric of current governing parties in some of these countries makes habituation less likely.

Similarly, the relationship between immigration preferences and concern on the one hand, and immigration-related policies on the other, is also likely to dynamic; so far this has only been studied statically (for example, Levy, Wright and Citrin Reference Levy, Wright and Citrin2016; Weldon Reference Weldon2006). Our estimates of mood and concern provide the opportunity to analyze how immigration and immigrant policy and opinion influence one another in more dynamic ways than has been possible until now. Thus in addition to allowing us to investigate the dynamic relationship between immigration numbers and opinions, our research has produced a valuable dataset of two different forms of immigration opinion that will facilitate analysis of important questions like these.

Supplementary material

Online appendices are available at https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123421000260.

Data availability statement

Replication data for this article can be found in Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9FO6LD.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dan Devine, Anastasia Gorodzeisky, Erik Kaufmann, Gizem Arikan and participants in the Trinity College Dublin Political Science Seminar series, where this article was presented on 16 October 2020, for their helpful comments.

Financial support

This work was supported by a British Academy grant to Claassen and McLaren (project number SRG18R1\181191)