In recent years, scholars of American democracy have pointed to growing affective polarization along partisan lines. Republicans and Democrats have developed strong emotional attachments towards co-partisans and hostility towards opposing partisans (Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Mason Reference Mason2015; Mason Reference Mason2018). This is worrying, because a well-functioning democracy requires that citizens and politicians are willing to engage respectfully with each other, even on controversial topics (Dahl Reference Dahl1967; Lipset Reference Lipset1959). Where we instead see mass affective polarization, we find intolerance and political cynicism (Layman, Carsey and Horowitz Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006) and reduced opportunities for collaboration and compromise (MacKuen et al. Reference MacKuen2010).

But is affective polarization limited to partisanship? In this article we argue that such polarization can emerge along lines drawn not just by partisan loyalties, but also by identification with opinion-based groups. We thus aim to significantly expand the scope of identities and political contexts that might be examined through the lens of affective polarization. Building on theories of social identity, we argue that significant political events can generate affective polarization. They do this by causing people to identify with others based on a shared opinion about the event. We study these opinion-based group identities in the wake of a critical juncture in British politics: the 2016 referendum on Britain's European Union (EU) membership. Our data suggest that affective polarization is not unique to partisanship, and that animosity across opinion-based groups can cut across longstanding partisan divisions.

We make three significant contributions. First, we present an original conceptualization of affective polarization based on an opinion-based in-group identity that focuses on three core components: identification with an in-group based on a common cause, differentiation from the out-group leading to prejudice and animosity, and evaluative bias in perceptions of the world and in decision making. Second, we examine this phenomenon empirically, using evidence from a large and diverse range of existing data, original surveys and novel experiments. We demonstrate the scope of affective polarization after the Brexit vote using implicit, explicit and behavioural indicators. Finally, we directly compare the impact of these new opinion-based Brexit identities to traditional partisan divisions. We find a similar degree of affective polarization for the new Brexit identities as for party identities in terms of identification, differentiation and evaluative bias. Moreover, Brexit identities cut across traditional party lines, meaning that affective polarization is neither restricted to partisanship nor a mere proxy for partisan affect. We argue that these new identities reflect pre-existing – but less-politicized – social divisions, like age and education, which were mobilized in the context of the referendum and have consolidated into the newly salient identities: Leave and Remain. These findings have important implications for the study of social identities and electoral democracy, not least because they demonstrate the emergence of strongly held political identities over a relatively short period of time.

The article proceeds as follows. We discuss the literature on in-group identities and affective polarization and present our conceptualization of opinion-based group identities. We then briefly introduce the context of the referendum, and proceed to show evidence of identification with the in-group, differentiation towards the out-group, and evaluative biases for both Brexit and partisan identities. All three effects are at least as large, if not larger, for Brexit identity compared to partisan identity. In conclusion, we discuss the sustainability of opinion-based cleavages and consider the conditions under which polarization along these lines is triggered.

Affective polarization and opinion-based groups

‘Inherent in all democratic systems is the constant threat that the group conflicts which are democracy's lifeblood may solidify to the point where they threaten to disintegrate society’

— Seymour Martin Lipset (Reference Lipset1959, 83).Political conflict and competition are at the heart of democratic life (Schattschneider Reference Schattschneider1960). The classic ideal of democracy is not one absent of conflict, but rather one in which a single conflict is not so entrenched and all-encompassing that society suffers (Dahl Reference Dahl1967). As the quotation from Lipset highlights, the health of democracy is threatened when conflicts solidify and political identities crystallize into polarized groups. At its most extreme, we see ethnically divided societies where government–opposition dynamics are almost entirely replaced by ‘ethnic outbidding’ (Rabushka and Shepsle Reference Rabushka and Shepsle1972) and where those in power view the democratic opposition as ‘the enemy of the people’ (Horowitz Reference Horowitz1993).

But mass polarization can also occur in societies not plagued by such divisions. The most prominent example is the increasing partisan polarization in American politics over the last few decades. While there remains some debate about the particular form of polarization at the mass level (Fiorina and Abrams Reference Fiorina and Abrams2008), there is a broad consensus that the US public has become more divided along partisan and ideological lines in recent years (Hetherington Reference Hetherington2009; Layman, Carsey and Horowitz Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006; Mason Reference Mason2018). Most notably, there has been rising interpersonal animosity across party lines, with Democrats and Republicans increasingly expressing dislike for one another (Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Layman, Carsey and Horowitz Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006; Mason Reference Mason2015; Mason Reference Mason2018). This phenomenon has been described as affective polarization, defined as an emotional attachment to in-group partisans and hostility towards out-group partisans (Green, Palmquist and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004; Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar2019). While affective polarization is often rooted in policy disagreement, it is distinct from ideological polarization. The latter concerns the extremity of political views, whereas the former is focused on hostility towards out-groups (Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012; Mason Reference Mason2015; Mason Reference Mason2018). In other words, affective polarization does not necessarily imply extreme policy disagreement. Studies on affective polarization in the US have shown that antipathy towards partisan opponents has escalated substantially among voters. This has meant that increased in-party favouritism has been matched by greater negative stereotyping and out-group discrimination (Iyengar and Westwood Reference Iyengar and Westwood2015; Lelkes and Westwood Reference Lelkes and Westwood2017; Mason Reference Mason2013; Mason Reference Mason2015; Mason Reference Mason2018; Miller and Conover Reference Miller and Conover2015).

There are many worrying consequences of affective polarization. Out-group animosity makes it more difficult for citizens to deliberate without prejudice and to seek diverse perspectives on controversial topics (Valentino et al. Reference Valentino2008). This in turn impairs democratic dialogue, collaboration and compromise (MacKuen et al. Reference MacKuen2010) and may lead to the erosion of trust in political institutions and the democratic legitimacy of elected leaders (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson2005; Layman, Carsey and Horowitz Reference Layman, Carsey and Horowitz2006). Affective polarization also exacerbates ‘filter bubbles’ and ‘echo chambers’ as people become unwilling to engage (in person or online) with people from the other side (Levendusky Reference Levendusky2013; Levendusky and Malhotra Reference Levendusky and Malhotra2016).

The concept of affective polarization is rooted in social psychological research on social identity and intergroup conflict, most prominently work on social identity theory by Henri Tajfel (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1970; Tajfel Reference Tajfel1979; Tajfel Reference Tajfel1982; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Stephen1979). The core idea is that group membership is an important source of pride and self-esteem. It gives each of us a sense of social identity. Yet it also means that our sense of self-worth is heightened by discriminating against, and holding prejudiced views about, the out-group (Tajfel Reference Tajfel1970; Tajfel Reference Tajfel1979). According to Tajfel and Turner (Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Stephen1979), there are three mental processes involved in shaping a social identity: social categorization, in which we distinguish between ‘us’ and ‘them’; social identification, in which we adopt the identity of the group we have categorized ourselves as belonging to; and social comparison, in which we compare our own group favourably to others. This desire to compare oneself with an out-group often, although not always, creates competitive and antagonistic intergroup relations. This then serves to further heighten identification with the in-group.

While social identity theory has proved extremely useful to political science (for an excellent review, see Huddy Reference Huddy2001), the identities considered, such as race, gender and partisanship, have been the same social categories common to psychological research (Mason Reference Mason2015; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Stephen1979). Partisanship has been particularly central: after all, ‘in the political sphere, the most salient groups are parties and the self-justifications that sustain group life are primarily grounded in – and constructed to maintain – partisan loyalties’ (Achen and Bartels Reference Achen and Bartels2016, 296). Less attention has been paid to other political identities,Footnote 1 even though self-categorized social identities are inherently subjective (McGarty et al. Reference McGarty2009; Turner Reference Turner and Tajfel1982). We argue that affective polarization can also stem from political identities defined by shared political opinions. Our argument builds on a recent strand in the social psychology literature that has developed the notion of opinion-based groups (Bliuc et al. Reference Bliuc2007; McGarty et al. Reference McGarty2009). Merely holding the same opinion as others is not sufficient for such a group to exist; rather, the shared opinion needs to become the basis of a social identity. In other words, people need to define themselves in terms of their opinion group membership in the same way that they would any other meaningful social group, such as a religious denomination or political party. Opinion-based groups emerge in the context of salient intergroup comparisons – that is, situations in which people are compelled to take sides on an issue. Prior research suggests that such identities may emerge, or crystallize, in response to dramatic events, such as wars or man-made disasters (McGarty et al. Reference McGarty2009; Smith, Thomas and McGarty Reference Smith, Thomas and McGarty2015). We argue they can also emerge from politically engineered events, specifically referendums.

We conceptualize the affective polarization of opinion-based groups as having three necessary components: (1) in-group identification based on a shared opinion, (2) differentiation of the in-group from the out-group that leads to in-group favourability and out-group denigration and (3) evaluative bias in perceptions of the world and in decision making. The starting point of affective polarization is that individuals must have internalized their group membership as an aspect of their self-identification. People form a social identity (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Stephen1979), but in this case it is based on group membership due to a common cause (McGarty et al. Reference McGarty2009) rather than organized around a social category. Similar to partisanship, ‘people think of themselves as members of a group, attach emotional significance to their membership and adjust their behaviour to conform to group norms’ (Bartle and Belluci Reference Bartle, Belluci, Bartle and Belluci2009, 5; see also Klar Reference Klar2014; Westwood et al. Reference Westwood2018).Footnote 2

The next step is that people must favourably compare their own group with the out-group (Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Stephen1979). Thus a second indicator of affective polarization is prejudice against (and stereotyping of) members of the out-group. The final step is that group competition must spill over into perceptions and political and non-political decision making. When it comes to opinion-based polarization, in-group bias will be an omnipresent feature that affects opinions and decision making in ways that go beyond the specific group conflict. People will evaluate political outcomes through the lens of their identity and make decisions based on that identity. To diagnose affective polarization, we should therefore observe all three of these factors – identification, differentiation and evaluative bias. In the remainder of the article, we examine these aspects of affective polarization across opinion-based group membership in the context of the 2016 referendum on Britain's EU membership.

The 2016 Brexit referendum

On 23 June 2016, British voters were asked in a nationwide referendum: ‘Should the United Kingdom remain a member of the European Union or leave the European Union?’ Although all the major parties in Parliament endorsed Remain,Footnote 3 52 per cent of the British electorate voted to exit the EU (‘Brexit’). This sent shockwaves through Britain and Europe. Never before had a member state decided to leave the EU. Although the vast majority of British parliamentarians voted to trigger the Brexit negotiation process, and both major parties campaigned on a platform of taking the UK out of the EU in the 2017 general election, the public did not universally rally behind Brexit. As we will show, the referendum and campaign triggered affective polarization over the issue of leaving or remaining in the EU that continued to divide society. Perhaps surprisingly, this occurred even though the question of EU membership and European integration was not a highly salient issue to the electorate – let alone a social identity – before the referendum. During the 2015 general election, only a year before the referendum vote, less than 10 per cent of people identified the EU as one of the two most important issues facing Britain,Footnote 4 and the EU issue played a minimal role in the election campaign. The opinion-based group identities ‘Leaver’ and ‘Remainer,’ which we will show came to take on considerable meaning for most British voters, have no long-term history in British politics. There were no labels for sides in the Brexit debate until the campaign itself.Footnote 5

The aftermath of the Brexit referendum is thus an apt case for the study of affective polarization around opinion-based groups. Social identity theory suggests that salient group identities emerge when people are compelled to take sides in a debate. A referendum that asks people to take a stance in favour (Leave) or against (Remain) exiting the EU is such a case. Moreover, the question of leaving the EU is unusual in that it cut across traditional party lines, meaning that the divisions resulting from the referendum were not immediately subsumed into the existing party divide. Yet, while a large body of literature has examined the determinants of voting behaviour in the referendum (Becker, Fetzer and Novy Reference Becker, Fetzer and Novy2017; Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley Reference Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley2017; Colantone and Stanig Reference Colantone and Stanig2018; Goodwin and Heath Reference Goodwin and Heath2016; Hobolt Reference Hobolt2016), we know much less about the way in which the vote subsequently divided people.

Data

To empirically examine affective polarization in the context of Brexit, we use multiple sources of survey and experimental data. All of our data come from public opinion surveys that are designed, and further weighted, to be representative of the British population. Table 1 presents an overview of these datasets. We rely on both the largest data source on public attitudes towards the referendum, the British Election Study 2016–2019 panel (Fieldhouse et al. Reference Fieldhouse2019), as well as a series of original public opinion surveys and survey experiments conducted between 2017 and 2019. Most of these surveys were conducted by YouGov, a prominent polling organization that uses quota sampling and reweighting methods to generate nationally representative samples from an online, opt-in pool of over 1 million British adults. We further supplement these data with surveys from Sky Polling, which applies similar methods to a panel of subscribers to the widely used Sky satellite television service.Footnote 6 This variety of data sources means that all our results come from nationally representative samples, but are not dependent on any single data source or survey methodology. Given the number and diversity of research designs and measures deployed, we describe each alongside its results in what follows.

Table 1. Data sources

a Question asks whether respondent thinks of themselves as ‘closer to the either the Leave or Remain side’.

b Question asks whether respondent thinks of themselves as a Leaver or Remainer.

Note: all survey respondents are drawn from online panels involving quota sampling, which are then weighted to be representative of the British population with respect to demographic characteristics.

Results

As we argued above, there are three key components of affective polarization along opinion-based lines – in-group identification, group differentiation (especially prejudice against members of the out-group), and evaluative bias in both perceptions and decision making. We thus begin by examining the prevalence of Brexit identities in the electorate using the British Election Study (BES), YouGov, Sky, and Tracker surveys as well as the strength and importance of these identities using the BES and Sky surveys. Next, we examine how those with Leaver and Remainer identities stereotype those on each side of the divide, and the extent to which they display prejudice against their Brexit out-group using the Sky and YouGov surveys. Then we show how these identities colour citizens' perceptions of economic performance in a manner that cuts across partisan identities. Finally, we measure the degree to which Brexit identities shape judgements of political and non-political choices using revealed choice conjoint experiments.

Identification

Our starting point is simply to measure the proportion of people willing to express an identity linked to the referendum. Table 2 shows two ways of measuring Brexit identity. The question included in the YouGov and Sky surveys asked people: ‘Since the EU referendum last year, some people now think of themselves as Leavers and Remainers, do you think of yourself as a Leaver, a Remainer, or neither a Leaver or Remainer?’ This mirrors the standard party identity question which asks people: ‘Generally speaking, do you think of yourself as Labour, Conservative, Liberal Democrat or what?’Footnote 7 The BES used a slightly different format which did not mention the two identity labels and encourages people to pick a side: ‘In the EU referendum debate, do you think of yourself as closer to either the Remain or Leave side?’

Table 2. Comparison of the strength of party and Brexit identities

a Question asks whether respondent thinks of themselves as ‘closer to the either the Leave or Remain side’, rather than whether they think of themselves as a Leaver or Remainer.

Note: the BES data have a total unweighted N of 31,197. The YouGov data have a total unweighted N of 3,326. The Sky data have a total unweighted N of 1,692 for party identity and 1,702 for Brexit identity. The emotional attachment scale consists of five questions (with a 1–5 Likert scale) that ask respondents with an identity whether (a) they talk about ‘we’ rather than ‘they’, (b) criticism of their side feels like a personal insult, (c) they have a lot in common with people on their own side, (d) they feel connected with other supporters of their own side and (e) they feel good when people praise their own side. High scores indicate greater agreement. These questions were only asked of those with a relevant political identity.

As Table 2 shows, the BES data revealed high proportions of people with a Brexit identity (over 85 per cent). Yet even with the weaker wording on the YouGov and Sky surveys, about three-quarters of people identified themselves as Leavers or Remainers even though the surveys were administered over 18 months after the referendum. Unsurprisingly, given the close referendum vote, there are roughly even numbers of Leavers and Remainers.Footnote 8 The total number of people with a Brexit identity is similar to the proportion of people who identify with a party. For example, the YouGov data show that 57 per cent of people identified with one of the two main parties. Not shown is an additional 16 per cent who identified with one of the other minor parties. In total, 74 per cent of people reported having a party identity, compared to 75 per cent with a Brexit identity in the YouGov data.Footnote 9 The prevalence of Brexit identities and traditional party identities is very similar. If anything, Brexit identities have become more widespread than partisan identities.

The bottom half of Table 2 also shows that both types of identities are equally strongly held. We show a measure of emotional attachment to people's own identity using a battery of five questions. These questions form a similar scale to that used by others (see Green, Palmquist and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004; Greene Reference Greene2000; Huddy, Mason and Aarøe Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015) and ask people whether they agree or disagree with the following with regard to their own identity:

• When I speak about the [respondent identity] side, I usually say ‘we’ instead of ‘they’

• When people criticize the [respondent identity] side, it feels like a personal insult

• I have a lot in common with other supporters of the [respondent identity] side

• When I meet someone who supports the [respondent identity] side, I feel connected with this person

• When people praise the [respondent identity] side, it makes me feel good

Response options for all items were ‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’, scored 1–5 and averaged.Footnote 10 For the two main party identities the average score is around the midpoint of the scale for both datasets. Interestingly, this is not much lower than the scores for responses to similar questions asked in the United States (Green, Palmquist and Schickler Reference Green, Palmquist and Schickler2004, 38; Huddy, Mason and Aarøe Reference Huddy, Mason and Aarøe2015, 7). More importantly for our purposes, these emotional attachment scores are slightly higher for Brexit identities than they are for party identities. This is especially obvious for the Sky data, which use the Brexit identity question which is most analogous to the party identity question.

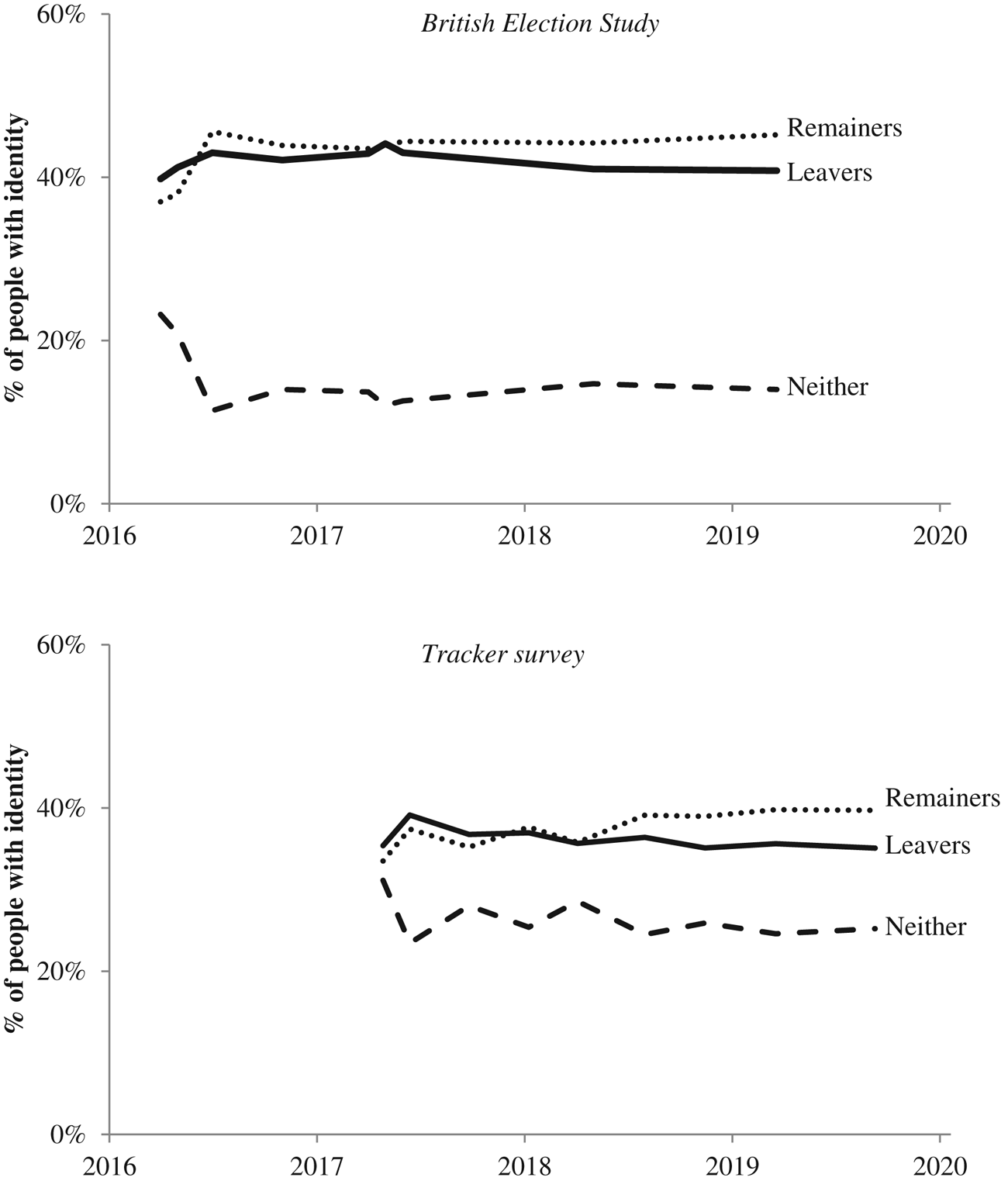

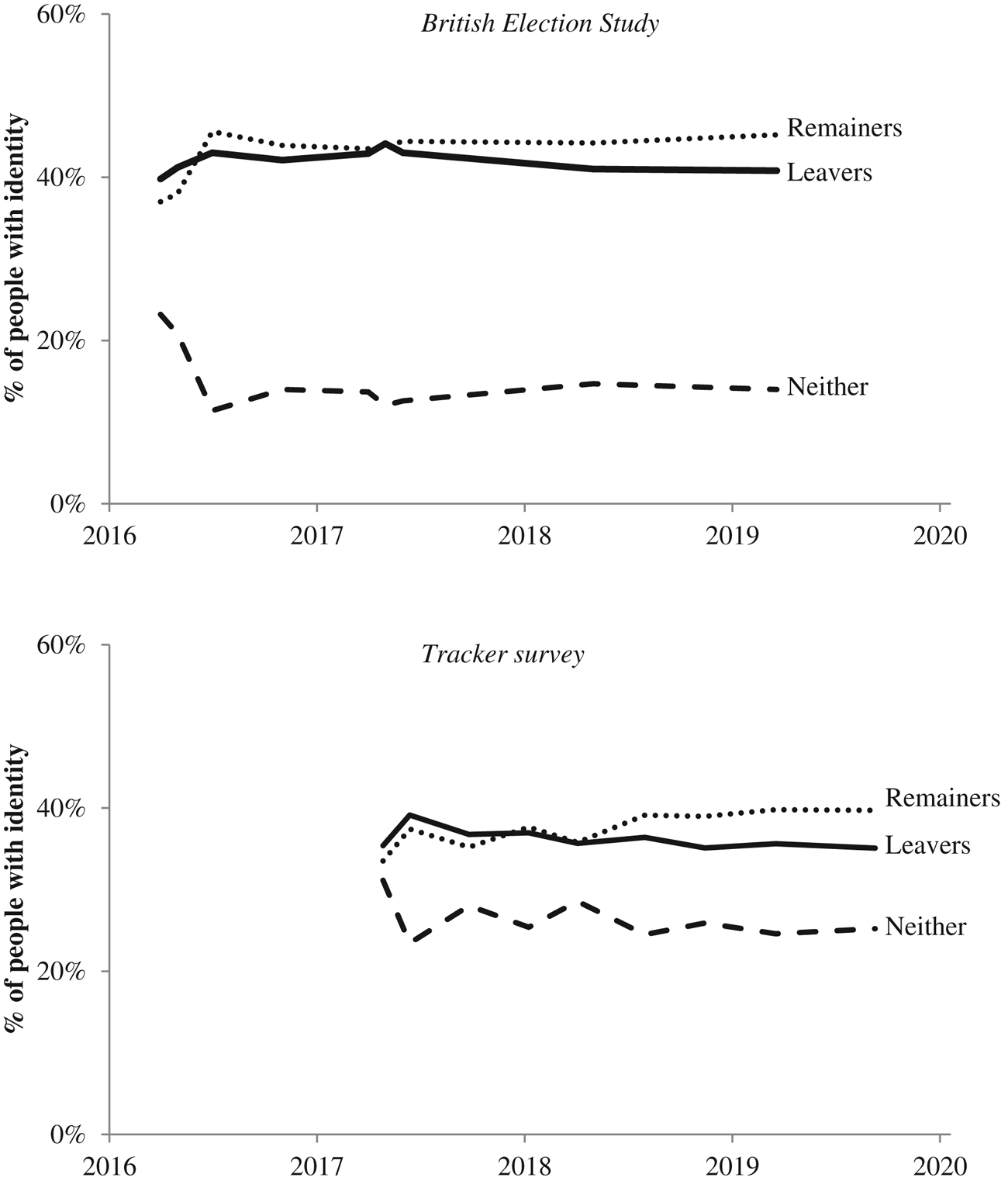

Overall, Table 2 reveals that not only were slightly more people willing to claim a Brexit identity than a party identity, but that people's attachment to that Brexit identity was, if anything, slightly stronger than their party identity. Moreover, these Brexit identities appear to be largely stable at the aggregate level. Figure 1 shows the numbers of people with a Brexit identity over time for nine waves of the BES from April 2016 until March 2019 and for nine waves of the Tracker survey from April 2017 until September 2019. Whether measured using the BES closeness question or the Tracker identity question, the numbers of people with either a Leave or Remain identity are almost completely static over time. Around three-quarters of people in Britain thought of themselves as Leavers or Remainers during the period of investigation. Most importantly, there is aggregate-level stability in the numbers within each identity grouping, suggesting the same kind of unmoving affective identity as partisanship. About half of those with an identity are Leavers and half are Remainers in any given month. These proportions have changed very little since the referendum. Indeed, the small increase in the number of Remainers is almost entirely due to an increased prevalence of that identity among people who did not, or were not able to, vote in 2016.Footnote 11

Figure 1. Brexit identities over time

Note: the British Election Study asks whether the respondents think of themselves as ‘closer to the either the Leave or Remain side’ and includes nine waves from April 2016 to March 2019. The Tracker data comprise nine cross-sectional surveys from April 2017 to September 2019 and asks whether people think of themselves as a Remainer or a Leaver.

Of course, while Brexit identities are a new aspect of British politics, they could reflect underlying societal divides that predate the referendum. Research into the determinants of the Brexit vote indicates that the referendum mobilized an underlying fault line between social liberals with weak national identities, who tend to be younger and have more educational qualifications, and social conservatives with stronger national identities, who tend to be older with fewer educational qualifications (Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley Reference Clarke, Goodwin and Whiteley2017; Curtice Reference Curtice2017a; Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2017; Hobolt Reference Hobolt2016; Jennings and Stoker Reference Jennings and Stoker2017). Using BES data, Appendix 2 confirms that the key socio-economic predictors of a Leave identity relative to a Remain identity are age and education. By contrast, measures of social class (such as income, occupation and housing tenure) continue to matter more for partisan identities than for Brexit identities despite a sharp decline in class voting in Britain in recent decades (Evans and Tilley Reference Evans and Tilley2017).Footnote 12 Analysis of a subset of the BES data in Appendix 2 also confirms that people with stronger British identities are more likely to hold a Leave identity, although the effect is not huge. These correlates of Brexit identity are clearly important, but in this article we are primarily interested in how such political divides manifest themselves as social identities that facilitate affective polarization. Whether the social and political forces driving diverging preferences about European integration are new or not, the labels provided by the referendum campaign certainly are. It is these labels which allow people to self-identify as a member of one opinion-based group or the other. They also facilitate differentiation, favouritism towards the in-group and animosity towards the out-group.

Differentiation

For the emergence of Brexit identities to constitute affective polarization, we expect to see Leavers and Remainers stereotype their in-group and out-group and express animosity towards the out-group. Figure 2 shows people's perceptions of their own and the other side in terms of three positive personal characteristics (intelligent, open-minded and honest) and three negative personal characteristics (selfish, hypocritical and closed-minded). This list of traits is similar to that used by Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes (Reference Iyengar, Sood and Lelkes2012) to examine partisan affective polarization over time and space. Respondents were asked how well they thought these six characteristics described the two sides on a five-point scale from 1 (‘not at all well’) to 5 (‘very well’). We focus on both differentiation along partisan lines, as a baseline, and differentiation along the lines of Brexit identity.

Figure 2. Perceived characteristics of own side and other side

Note: these are mean scores on a 1–5 Likert scale of agreement that these characteristics describe people with a particular political identity. Data are from the YouGov survey in September 2017. For the party identity descriptions, the unweighted N is 1,648. For the Brexit identity descriptions, the unweighted N is 1,678.

The top two graphs in Figure 2 show mean perceptions by party identity. We see a familiar story. Perceptions of Conservative supporters, graphed on the left, are very different for people who are themselves Conservative identifiers compared to those who are Labour identifiers. Conservative partisans score their in-group above 3.5 in terms of intelligence, honesty and open-mindedness, but are much more reluctant to say that their in-group are selfish, hypocritical or closed-minded. The exact opposite is true for Labour partisans, who score Conservative supporters at nearly 4 in terms of their selfishness, hypocrisy and closed-mindedness, but are extremely unlikely to say that Conservatives might be intelligent, open-minded or honest. The top right-hand graph shows perceptions of Labour supporters. Again, Labour identifiers only attribute positive characteristics to their in-group while Conservative identifiers only attribute negative characteristics to their out-group.

Fascinatingly, we see the very same patterns for Brexit identities in the two bottom graphs. Remainers and Leavers are much more likely to attribute positive characteristics to their own side and negative characteristics to the other side. The magnitude of these differences is very large. Remainers' average score for the three positive characteristics about their own side is 3.9, while their average score for the three negative characteristics about their own side is just 1.9. The gulf between agreement with negative and positive attributes of the out-group is also huge. For Remainers' perceptions of Leavers, the average score for the three positive characteristics is 2.4, yet the average score for the three negative characteristics is 3.6. Nor are these views of Leavers and Remainers driven by party identity. Appendix 3 contains four ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions that predict whether people have positive or negative views of both sides using both party identity and Brexit identity. All four models show very large effects of Brexit identity and very weak effects of party identity on perceptions of Remainers and Leavers.

When asked about their interest in forms of social interaction with members of the in-group and out-group, people also readily expressed prejudice towards the out-group and favouritism towards the in-group. Table 3 shows the proportions of respondents who said they would be happy with a child of theirs marrying someone from the other side and the proportion that are happy to ‘talk politics’ with someone from the other side. Only around half would be happy to talk politics with the other side, whether that side is defined by Brexit choice or party identity. Even more strikingly, only a third, on average, of those with a Brexit identity would be happy about a prospective son- or daughter-in-law from the other side. Levels of partisan prejudice are only slightly higher.

Table 3. Prejudice against the other side

Note: the YouGov data have a total unweighted N of 3,326. The Sky data have a total unweighted N of 1,692 for party identity and 1,702 for Brexit identity.

Evaluative bias – perceptions

The final indicator of affective polarization is evaluative bias in perceptions and decision making. We start by examining how Brexit identities shape people's views of the world. There is a wealth of evidence of the partisan ‘perceptual screen’ when it comes to economic performance. Supporters of parties in government consistently tend to think that the economy performed better than supporters of opposition parties (Bartels Reference Bartels2002; Bisgaard Reference Bisgaard2015; De Boef and Kellstedt Reference De Boef and Kellstedt2004; Enns, Kellstedt and McAvoy Reference Enns, Kellstedt and McAvoy2012; Evans and Pickup Reference Evans and Pickup2010; Tilley and Hobolt Reference Tilley and Hobolt2011; Wlezien, Franklin and Twiggs Reference Wlezien, Franklin and Twiggs1997). As Achen and Bartels (Reference Achen and Bartels2016, 276) bluntly put it, people ‘use their partisanship to construct “objective facts”’. A similar process of motivated reasoning should apply to people with Brexit identities. Leavers, who were on the winning side in the referendum, should have a more positive view of past economic performance than Remainers. We asked respondents in January 2018 how they thought the economy had performed over the last 12 months on a 1–5 scale (the standard way of measuring retrospective economic perceptions). Table 4 shows the results of an OLS regression predicting people's scores on this scale with party identity and Brexit identity as predictors.Footnote 13 Higher scores indicate a rosier view of economic performance during 2017.

Table 4. Predicting retrospective economic perceptions

Note: the data come from the January 2018 Tracker survey and have a total unweighted N of 1,418. The dependent variable asks respondents ‘How do you think the general economic situation in this country has changed over the last 12 months’ with five options (got a lot worse, got a little worse, stayed the same, got a little better and got a lot better) coded from 1–5. * = p < 0.05

As expected, there is a gap between Conservative and Labour identifiers’ assessments of the economy. Conservative identifiers, whose party was in government, were slightly over one-half of a point on the 1–5 scale more positive about British economic performance in 2017 than Labour identifiers. Yet even holding party identity constant, we see large effects for Brexit identity. Leavers are almost three-quarters of a point more positive than Remainers. Brexit identity is thus more likely than party identity to produce biased retrospective views of the economy.

Evaluative bias – decision making

Another component of evaluative bias that we examine is how Brexit identities shape decision making outside the political realm. We are interested in whether these social identities also spill over into decisions, and possibly even discrimination, on non-political matters. We conducted two similar conjoint experiments that asked respondents to choose between alternative candidates to be director-general of the BBC and, separately, to be a lodger in their own home. The advantage of using a conjoint design is that it allows us to uncover the relative influence of different factors in how people make decisions over bundled outcomes (Auspurg and Hinz Reference Auspurg and Hinz2014; Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014; Jasso Reference Jasso2006). Borrowed from marketing research, where it is used to study purchasing decisions, this methodology has recently been used in public opinion research to study complex opinion formation processes such as support for immigration policies (Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner Reference Bansak, Hainmueller and Hangartner2016; Hainmueller and Hopkins Reference Hainmueller and Hopkins2015), voting for candidates (Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto Reference Hainmueller, Hopkins and Yamamoto2014) and preferences for labour market reform (Gallego and Marx Reference Gallego and Marx2017). In a conjoint study, participants are shown a series of vignettes that vary according to a determined set of features, with combinations of features randomly varied. In our studies, each sample was conducted on a distinct sample of approximately 1,600 respondents (see Table 1); each respondent selected from choices in five pairs of fully randomized candidate profiles. The features in the two designs varied along salient characteristics, such as age, sex, hobbies and work experience in the case of the lodger experiment and age, sex, education and career background for the BBC experiment. In both experiments we also included two political features – the candidate's partisan position in the 2017 UK general election (Conservative, Labour or none) and their stance on the 2016 referendum (Leave, Remain or none).

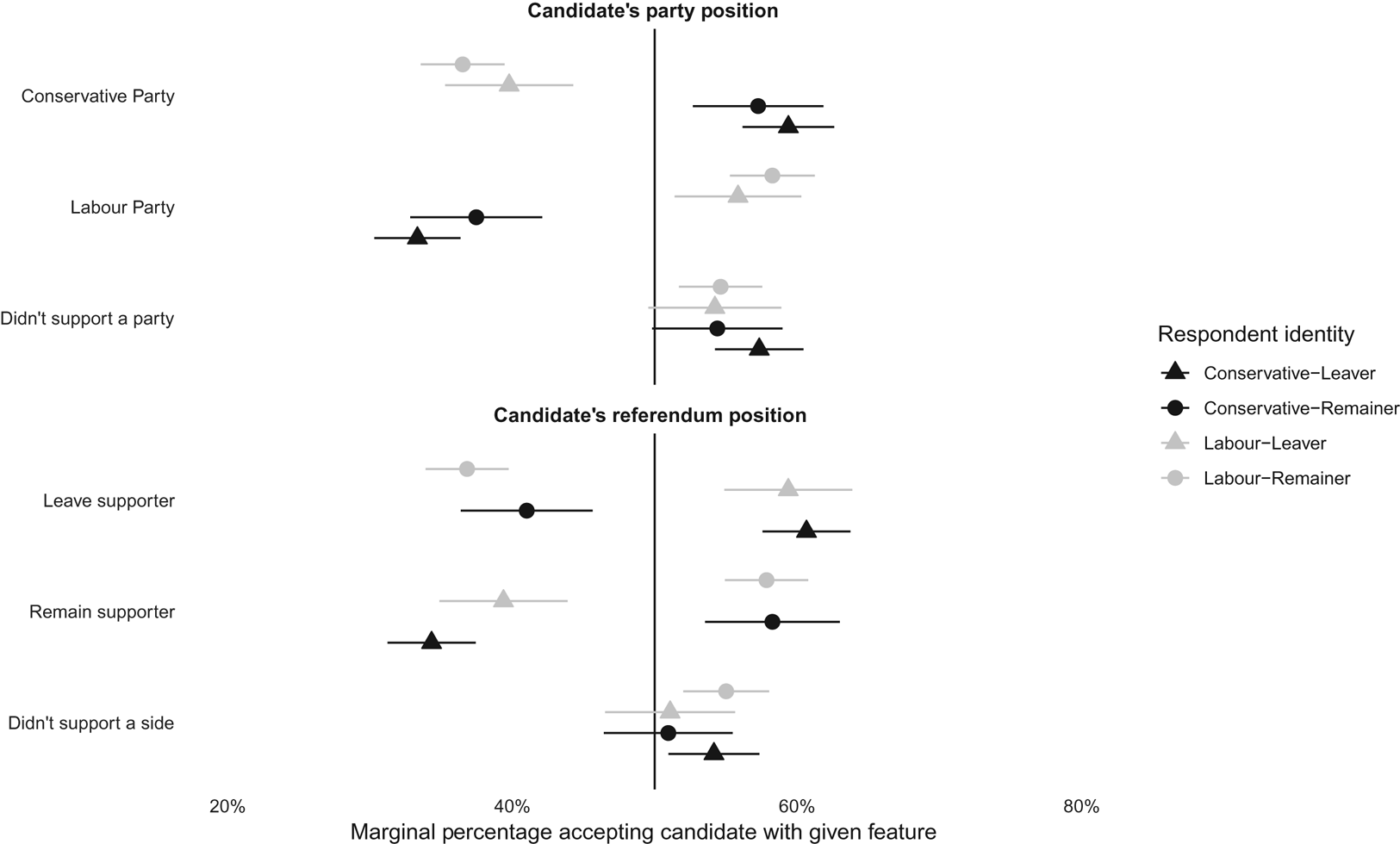

The full results of preferences for both the director-general and lodger experiments are in Appendix 4, but Figures 3 and 4 present the key results. Here we show the marginal mean outcomes for the two political factors – that is, the percentage of times respondents chose profiles with the specified feature, marginalizing across the other features.Footnote 14 Figure 3 shows the marginal means for the party position and referendum position features of the BBC director-general experiment separately for people who identified as Conservative and Leaver; Conservative and Remainer; Labour and Leaver; and Labour and Remainer. We find large effects of partisanship and Brexit identity. In the upper half of Figure 3, Labour partisans prefer a Labour-supporting director-general; Conservative partisans prefer a Conservative supporter. These effects are matched in size by the difference in preferences between Leavers and Remainers shown in the lower half of Figure 3. Regardless of their partisanship, respondents prefer the head of the BBC to have a similar Brexit identity. For example, while less than 40 per cent of Labour-identified Remainers would pick a candidate who was a Leaver, holding everything else equal, nearly 60 per cent of Labour-identified Remainers would pick a fellow Remainer. On average, the effects of Brexit identity are slightly greater than partisanship. We see very similar patterns in Figure 4 for the lodger experiment. Remainers prefer to live with a fellow Remainer than a Leaver, and Leavers prefer to live with a fellow Leaver than a Remainer. Again, these effects are large, and bigger than the partisan effects. The Brexit divide cross-cuts, and even exceeds, the partisan divide.

Figure 3. Results from BBC Director-General conjoint experiment by Leave and Remain identity

Note: these are marginal mean outcomes from a discrete choice conjoint experiment, estimated separately for different types of respondents by their partisan and Brexit identity. Data are from the BBC Director-General YouGov survey (n = 1,653) conducted in October 2017. Error bars reflect 95 per cent confidence intervals, clustered by respondent with each respondent completing five binary choice decision tasks.

Figure 4. Results from lodger conjoint experiment by Leave and Remain identity

Note: these are marginal mean outcomes from a discrete choice conjoint experiment, estimated separately for different types of respondents by their partisan and Brexit identity. Data are from the Lodger YouGov survey (n = 1,669) conducted in October 2017. Error bars reflect 95 per cent confidence intervals, clustered by respondent with each respondent completing five binary choice decision tasks.

Discussion

Huddy (Reference Huddy2001, 137) notes that ‘[p]olitical behavior researchers are often struck by the absence of group conflict despite the existence of distinct and salient groups'. Much research has therefore focused on the rare cases in which long-standing social identities generate considerable tension, such as the partisan divide in the United States or ethnic tensions in other parts of the world. Yet we describe a situation in which distinct and salient groups emerged over a relatively short period of time and engaged in group conflict on par with that of partisanship. Building on theories of social identity, we advance the conceptualization of affective polarization, arguing that such animosity can be mobilized across opinion-based groups in the context of significant political events. Unlike partisan loyalties, opinion-based groups are defined by shared opinions on a specific issue or cause. We study these opinion-based group identities in the wake of a critical political juncture: Britain's 2016 referendum on EU membership. Our results clearly suggest that affective polarization is a phenomenon not unique to partisanship. Indeed, we show that polarization along the Brexit divide is as large, or larger, than partisan affective polarization, and its effects cross-cut partisan identities.

We thus make a significant contribution to the political behaviour literature by developing the notion of affective polarization along these opinion-based group lines. Empirically, we demonstrate these polarization dynamics outside the US context and along nonpartisan lines in all three areas of affective polarization – identification, differentiation and evaluative bias. While theorizing about the origins of affective polarization remains underdeveloped, our work suggests that long-term ideological polarization, at either the elite or mass level, is unlikely to be the only cause of new opinion-based identities. Brexit-related identities and polarization emerged despite no longstanding Leave/ Remain divide and in a manner that cut across partisan identities. This implies that shorter-run dynamics can play an important role in triggering democratically occurring forms of prejudice, discrimination and bias. While our empirical focus here is Brexit, the notion of affective polarization along opinion-based group lines could apply elsewhere, where political issues are sufficiently salient and divisive to give rise to social identities and out-group animosity. For example, this framework could be applied to the issue of Catalan independence, which has become very politicized and divisive in Spain, especially in the mobilization leading up to and following the 2017 Catalan referendum on independence (Criado et al. Reference Criado2018; Hierro and Gallego Reference Hierro and Gallego2018; Oller i Sala, Satorra and Tobeña Reference Oller i Sala, Satorra and Tobeña2019).

At the same time, however, we do not think that all issue debates – regardless of their degree of underlying disagreement – can generate the consistent and intense patterns of polarization demonstrated here. Part of the reason for that is the prevalence of the underlying opinion-based group identities and their perceived importance to large portions of the British public. Although some people hold views on many different issues and consider those views to be personally important, such issue publics are generally understood to be small and narrow (Converse Reference Converse and Apter1964; Krosnick Reference Krosnick1990). In the case of Brexit, opinion-based identities are held by over three-quarters of the public, and the intensity of those identities is similar to partisanship. The national referendum and surrounding debate seem necessary, but insufficient, to have generated such polarization. This is important because not all events of direct democracy, or political debates more generally, create such deep divides. Referendums are frequent occurrences in many democracies, yet few appear to generate salient and lasting polarization. In this case, we suspect that the cross-cutting nature of partisan and Brexit identities played an important role. Most national referendums reflect the playing out of elite partisan competition at the mass level (Prosser Reference Prosser2016), and many EU referendums showcase second-order evaluations of national governments (Garry, Marsh and Sinnott Reference Garry, Marsh and Sinnott2005; Hobolt Reference Hobolt2009). But the Brexit referendum occurred orthogonally to the traditional partisan divide and has still not been fully subsumed into normal lines of party competition.

This article also raises other number of important questions. For example, how does affective polarization along opinion-based group lines evolve in the long run: does it fade away as the political event that triggered the social identities becomes less salient? It is certainly possible that Brexit identities will eventually become less important to people now that Britain has left the EU. Another possibility is that affective polarization on the Brexit issue will lead to a realignment of the British political system. According to Carmines and Stimson's seminal work on issue evolution, realignments are precipitated by the ‘emergence of new issues about which the electorate has intense feeling that cut across rather than reinforce existing bases of support for political parties’ (Reference Carmines and Stimson1981, 107). We have shown that the Brexit referendum led to the emergence of intensely felt identities that cross-cut partisan divisions. This could mean that affective polarization along Brexit lines will eventually lead to a more fundamental change in the UK party system. The major political parties could align their positions firmly with one of the two opposing positions on future UK–EU relations, leading voters to discard old party attachments in favour of new patterns of support. Indeed, we could see a similar change in Britain, albeit precipitated in a very different way, to the Southern realignment in the United States (Stanley Reference Stanley1988; Valentino and Sears Reference Valentino and Sears2005) and the shift from the main dimension of party competition being economic left–right policy to social conservative–liberal policy. Studies of electoral competition in the 2017 and 2019 UK general elections give some indications that this realignment has already started to occur (Curtice Reference Curtice2017b; Cutts et al. Reference Cutts2020; Heath and Goodwin Reference Heath and Goodwin2017; Hobolt Reference Hobolt2018; Hobolt and Rodon Reference Hobolt and Rodon2020; Jennings and Stoker Reference Jennings and Stoker2017; Prosser Reference Prosser2018; Tilley and Evans Reference Tilley and Evans2017).

Whether there is a party realignment or not, it is clear that the EU referendum activated an important new divide in British society. Intensely felt political division seems to be an all-too-familiar feature of 21st century democratic politics. Ultimately, any time such divisions emerge, normative questions are raised about the implications for democratic society, what might ameliorate the tension and how democratic practice might be improved. Answers to these three questions might be the lack of democratic deliberation, the potential value of a more deliberative democracy and deeper institutionalization of deliberative processes, respectively (Dryzek and Niemeyer Reference Dryzek and Niemeyer2006; Thompson and Gutmann Reference Thompson and Gutmann1996). The deliberative response is to seek consensus by airing rival arguments. Yet citizens’ apparent unwillingness to even speak across the divide, let alone respect or befriend one another, would seem to undermine the possibility of a deliberative cure. Other answers need to be found. The task may not be to create consensus across the divide, but instead to help citizens to recognize one another not as enemies and out-groups, but as adversaries with a shared collective identity disagreeing over the outcomes of policy debate (Mouffe Reference Mouffe1999). In that sense, perhaps political scientists and political theorists should move beyond trying to understand how to overcome political disagreements, and focus more on how those disagreements can be sustained without yielding deleterious social consequences.

Supplementary material

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/35M5CV and online appendices at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123420000125.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Economic and Social Research Council – UK in a Changing Europe programme for generous support of this research (ES/R000573/1). Previous versions of this article have been presented at the University of British Columbia, Durham University, the University of Exeter, the University of Zurich, the ECPR-SGEU conference in Paris, the EPSA conference in Vienna and the APSA conference in Boston. We are grateful to the participants at these events for their insightful comments and suggestions, and in particular we would like to thank Alexa Bankert, John Curtice, Andy Eggers, Leonie Huddy, Lily Mason, Anand Menon, Yphtach Lelkes, Toni Rodon and Chris Wratil. We would also like to thank the anonymous reviewers and the BJPolS editorial team for their constructive assessment and guidance. Any remaining errors and imperfections are our own.