Between 1958 and 2008 political science journals published nearly 800 articles about the politics of public policies spreading from one government to another, a phenomenon commonly referred to as ‘policy diffusion’. More than half of these articles have been published in the last decade of that period, indicating a dramatic surge in interest in diffusion. We believe that it is time to pause and take stock of where we have come from, where we currently are, and where we could and should be going in future scholarship. Although such reviews and assessments have been made from time to time within the subfields of political science and policy studies,Footnote 1 our goal here is to look not only within, but also across subfields in order to provide a more complete overview of the literature and to integrate the insights of multiple fields.Footnote 2

Examples of the usefulness of integration are plentiful. In the case of international relations (IR), trends beginning in the late twentieth century and continuing into the twenty-first include the rise of globalization, where power and information are increasingly decentralized and where barriers to the exchange of ideas, information and resources are in decline. Simultaneously, however, we see nations turning increasingly to centralized, regional bodies (e.g., the European Union (EU), the African Union (AU) and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) to handle interstate affairs).Footnote 3 These trends point towards the increasing relevance of questions related to the potential benefits of devolution versus centralization, longstanding issues confronted by policy diffusion scholars studying American federalism. As scholars turn towards these questions that are central to international relations,Footnote 4 they will benefit from communication with earlier diffusion scholarship in the domestic realm.

Conversely, American politics scholars have set aside key points about the diffusion of norms across governments, despite early suggestions by Walker that socialization processes could be of great import in the diffusion of policies.Footnote 5 Rather than beginning such analyses anew, American politics scholars would benefit from confronting and building upon the extensive work on norm diffusion within the IR literature.Footnote 6

Such opportunities for mutual engagement and scholarly progress abound. Comparative politics scholars have yet to tackle the concepts of policy reinvention and evolution, which have received attention within the American politics literature.Footnote 7 Comparative politics and IR scholars separately study the spread of exactly the same policies, despite different emphases on internal politics or international actors; and qualitative and quantitative advances in policy diffusion scholarship are relevant across fields of study and approaches, even if scholars have not fully recognized these mutually beneficial advancements.

More broadly, as political science moves toward its thousandth published article on policy diffusion, the piecemeal and disconnected nature of the research to date has left us intellectually poorer than we should be. Although many illustrative examples have emerged about the politics surrounding the spread of policies, we are nowhere near having a systematic, general understanding of how diffusion works. We believe that such a goal is more easily attained when scholars are aware of one another's path-breaking work and when they share a common language in which to discuss their insights. In an attempt to move the scholarly community closer to such an ideal, in this article we review the literature, lay out the key parameters of diffusion research, and suggest paths to move this broad research agenda forwards.

More specifically, in the next section we begin by documenting the hundreds of studies published on policy diffusion. We report the results of a network analysis designed to identify the central arguments in each field and also to identify which areas have fewer strong connections to other fields of study. We use this quantitative exercise to provide a brief assessment of the diffusion literatures in American politics, international relations and comparative politics. With that background in hand, we detail what is known and what is ripe for further study regarding the who, what, when, where, how and why of policy diffusion research.

Divided We Write

In order to characterize the literature on diffusion, and to see the ways in which theoretical ideas and empirical strategies have developed over time and across subfields, we first identify the set of studies that focus on diffusion. To do so, we begin by adopting a very simple and general definition of policy diffusion, one that is consistent with the conceptions of a number of influential authors.Footnote 8 Specifically, diffusion occurs when one government's decision about whether to adopt a policy innovation is influenced by the choices made by other governments. Put another way, policy adoptions can be interdependent, where a country or state observes what other countries or states have done and conditions its own policy decisions on these observations.Footnote 9

Based on this concept, we began by building a database of all political science articles on diffusion published between 1958 and 2008.Footnote 10 Our first step in this process was to determine which journals to include. We proceeded by using Giles and Garand's list of the top fifty political science journals (which they compiled based on ISI rankings),Footnote 11 supplemented by the journals American Politics Research (formerly American Politics Quarterly), Governance, and Publius, which each contain numerous important diffusion articles but are not among Giles and Garand's top fifty.Footnote 12 Although a handful of political science studies of policy diffusion have been published as books,Footnote 13 the vast majority have been published as journal articles; hence, a focus on articles is defensible and appropriate.Footnote 14

Once we identified the relevant set of journals, we conducted a search of all articles published in these journals, using JSTOR, other internet databases, and hard copies of journals not available in an electronic format. Because not all articles about diffusion use the term ‘diffusion’, we broadened our search to include the following terms: diffusion, convergence, policy transfer, race to the bottom, harmonization and contagion, all of which are commonly used in the literature on policy diffusion as we define it above. If any of these terms were included in the title or abstract of an article in these fifty-three journals, we then read the abstract to make sure that the article was about diffusion. This process produced 781 articles.

Finally, we coded each article as belonging to one of four categories: American politics (AP), comparative politics (CP), international relations (IR) and other.Footnote 15 Two of us separately categorized each article, based on the journal in which it was published, the author's main field of study and the title of the article. For example, papers published in State Politics and Policy Quarterly were coded as belonging to the American politics subfield; those published in Comparative Political Studies were coded as comparative; and those published in International Studies Quarterly were coded as IR. For the primary subfield of the authors, we used data from Bernard Grofman's website,Footnote 16 supplemented by looking at authors’ webpages.

In cases where the two coders agreed on how to categorize the paper, that categorization was final; in all other cases, the third author read the abstract and coded the paper based on that reading.Footnote 17 The initial coders disagreed on 150 of our 781 cases (19 per cent). Not surprisingly, the vast majority of cases in which the initial coders disagreed (130 of 150) represented cases at the intersection of comparative politics and international relations. For studies at this intersection, we coded them as IR if they emphasized the role of international institutions, if they ascribed a primary role to coercion, or if the abstract demonstrated that the article relied heavily on theoretical ideas more prevalent in IR than comparative politics (for example, constructivism). Otherwise we placed them in the comparative politics category.

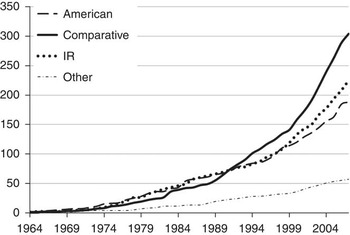

Figure 1 demonstrates how the literature on diffusion has developed overall and in each subfield. Several aspects of the overall pattern are worth noting. First, the comparative politics subfield has produced more studies of policy diffusion than the other two subfields, with 307 articles. IR has produced 226 studies, while there have been 189 studies of diffusion in American politics and 59 studies that we categorized as ‘other’. Secondly, each of the subfields shows a roughly similar pattern – a pattern that looks very much like the beginning of the standard S-curve produced by policy adoptions – with only a handful of articles published in the 1960s, an average of two articles per subfield per year throughout the 1970s, a steady increase throughout the 1980s and 1990s (when an average of four and six articles appeared per field per year) and a dramatic increase in the 2000s, when the rate of publication across all subfields more than doubled, as compared to the 1990s. Thirdly, although all subfields showed a steady increase starting in the 1970s and then a steeper rise later on, the subfield of comparative politics produces a pattern that differs from those found in AP and IR. Studies in CP lagged slightly behind AP and IR in the 1970s and 1980s in quantity, but then showed a much steeper rise in the 1990s and continued to increase more rapidly in the 2000s.

Fig. 1 Cumulative number of policy diffusion articles, by subfield

To discern lessons emerging from this collective body of scholarship, it is essential to uncover the key ideas and to determine whether scholars in each field are adequately recognizing and joining the scholarly debates in other subfields. Many approaches may be relevant: a detailed reading of this literature forms the basis for the discussion later on, and an examination of the frequency of citations within and across fields will likewise be informative. But before turning to these alternatives, we first draw on network analyses in order to determine which papers have been more influential and, more generally, to shed light on the degree to which each subfield is integrated with the others. To begin, we discuss the relationship between American and comparative politics, before turning to similar discussions of the relationships between AP and IR and between IR and CP.

The network analyses cluster together articles based on the degree to which they cite one another and how those related articles are in turn cited by others. These lead to clusters of articles that are central and well integrated into the network, some articles that serve as bridges across different parts of the network, and additional exterior articles that form clusters but are somewhat less central to the largest scholarly debates being conducted.Footnote 18 In addition to classifying each article by political science subfield, we identified the primary search term used to detect the article, as well as the subject area concerning what is diffusing in the article.Footnote 19 These latter coding schemes help to interpret the figures generated from the network analyses we conduct.Footnote 20

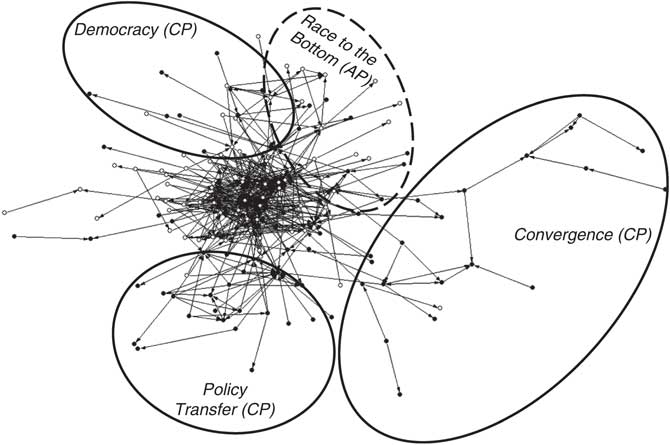

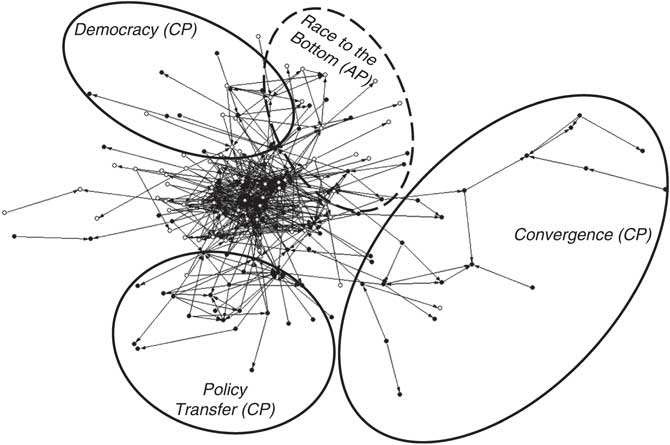

The development of diffusion scholarship in American and comparative politics has taken very different paths. Figure 2 highlights a striking difference: in American politics, diffusion scholarship is tightly clustered, with most authors drawing on a core set of diffusion studies.Footnote 21 In contrast, comparative politics does not exhibit a discernible central cluster. The relationship between the subfields might best be described as connected, but not integrated, as only a few comparative studies fall inside the core American cluster.

Fig. 2 Networks of American politics (white points) and comparative politics (black points) studies of diffusion

Outside the main cluster of AP articles (which typically study policy choices at the state level) is a small group of articles to the upper right of Figure 2, more tightly focused on ‘race to the bottom’ concerns (typical in welfare policy making).Footnote 22 Such a focus has led authors of these studies to be more interested in the negative consequences of policy making in these areas and in decentralization, rather than focusing on issues that would tightly align them with the policy diffusion literature directly.Footnote 23 In this area, there are connections among CP and AP scholars interested in similar concepts. In contrast, the lower left cluster in Figure 2 is composed almost entirely of comparative politics articles written on ‘policy transfer’.Footnote 24 These studies typically focus on a single policy in a single country to assess the extent to which the policy's origins are found to be heavily influenced by other countries’ policy choices. Although still part of policy diffusion studies, such an approach differs markedly from studies of how policies flow to and from multiple governments over time.

To the upper left in Figure 2 is a small literature on the spread of democracy across countries. These studies, although definitely linked to the diffusion literature, are distinct in their focus on the spread of governmental institutions rather than policies.Footnote 25 And to the right in Figure 2 is a series of studies in comparative politics on the convergence of policies and standards across countries. Rather than judging solely how policies spread over time, this literature confronts the related question of whether these governments are heading in the same direction or to the same endpoints.Footnote 26 Such studies are almost entirely absent in American politics.

While the AP and CP studies of diffusion are, therefore, somewhat loosely connected, the divide between American politics and international relations scholarship on diffusion is even starker. Figure 3 shows once again a tight cluster of AP articles, divided only by the related race-to-the-bottom literature. Whereas CP scholars also contributed to race to the bottom studies, this topic has not been of concern to IR scholars. Instead, as shown on the left of Figure 3, the IR literature on diffusion focuses heavily (and unsurprisingly) on the spread of conflict.Footnote 27

Fig. 3 Networks of American politics (white points) and international relations (grey points) studies of diffusion

Two other groupings appear among IR scholarship in Figure 3. To the upper right, as with the comparative politics literature, scholars in international relations have been concerned with convergence. In many cases, IR scholars in this area study the role of international organizations in facilitating similar chosen ends across countries. Connected somewhat to the convergence studies, but still quite distinct from AP studies of policy diffusion, is IR scholarship on norm diffusion.Footnote 28 In these studies, the authors examine how socialization processes and identity politics shape the spread of norms across the international community. Although relevant to state and local politics in the United States, these concepts have not been explored in the American politics literature on diffusion.

In contrast to the divides between American politics and either comparative politics or international relations, these two latter subfields have been well integrated. As shown in Figure 4, there is still a distinct IR literature on war and a separate CP literature on policy transfer. Except for those two clusters, however, the network of scholarship shows these two subfields to be nearly interchangeable. That is, one would find it difficult to guess a particular node's subfield simply by looking at the nodes surrounding it. The relatively high level of integration between IR and CP is reflective of a more general trend towards integration between the two fields, particularly in international and comparative political economy.Footnote 29 Articles with the ‘convergence’ search term, seen as separate from American politics in Figures 2 and 3, are now as central in the network as those discovered with the ‘diffusion’ search term. Moreover, scholars in both IR and CP cite one another's work in these areas as if there were no discernible subfield boundaries. Perhaps equally striking is the absence of distinct clusters for democracy and norm diffusion, found in the earlier figures. Articles in these areas have been seamlessly integrated with other scholarship across these two subfields. The lessons drawn from democratization are used in other policy diffusion studies, and the spread of norms is seen as a natural and central part of such scholarship.

Fig. 4 Networks of comparative politics (black points) and international relations (grey points) studies of diffusion

The preceding figures demonstrate that bridge building between subfields has been somewhat inconsistent. Although there have been some promising connections, our reading of the literature and subsequent discussion indicates that there is sufficient overlap in scholarly interests (and practical applications) across the fields to warrant further integration of diffusion scholarship. Failure to draw on studies across subfields may prevent analytic sharpening or a better understanding of the scope conditions under which a particular concept or mechanism operates. At the same time, outsiders are denied the opportunity to become familiar with and utilize concepts, mechanisms and methodologies that potentially provide useful tools to answer their questions of interest. Further, diffusion scholars run the risk of inefficiency and redundancy.

Before turning to fuller qualitative assessments of these literatures and how they could be better integrated, we present one additional quantitative summary of the data used in our network analyses. Table 1 provides a listing of how frequently each subfield's top-cited articles are cited by those in other fields. The top articles in American politics have been cited within that subfield's diffusion literature between sixteenFootnote 30 and fifty-sixFootnote 31 times each. In contrast, American politics scholars have cited the top five articles in the other subfields a total of only fourteen times. It should not be surprising, therefore, that the AP clusters in Figures 2 and 3 were so tight and isolated. Relative to such insularity, three of the top six articles cited by comparative politics diffusion scholars are from other subfields. Indeed, across subfields, most of the connections have been initiated from CP (i.e., from comparative articles citing core American articles). IR scholars draw more heavily on CP studies than on AP works.

Table 1 Comparing Citations within and across Subfields

The insularity of American politics does provide some advantages. For example, questions asked and conjectures made in early work are now being taken up with empirical knowledge and methodological rigour not possible in earlier studies. The impact of vertical (e.g., national to state) diffusion dynamics, and the new emphasis on learning versus competition (assumed or suggested but not tested in early work) provide examples of this continuity. Despite these linkages, two obstacles to forward progress are worth noting. First, within the tight community of American politics diffusion scholarship, the piecemeal nature of most studies makes generalization difficult. This is particularly the case when variables or mechanisms found to operate in one study are left out of others, leading to concerns of omitted variable bias. Secondly, there are also drawbacks to insularity. Among them is a tendency not to look beyond one's own community for ideas that may be useful in answering relevant questions. For example, much of the early AP scholarship focused solely on whether policies were geographically clustered, rather than on whether and how they spread beyond geographic boundaries. Had there been a search for broader concepts, the top comparative studies surely would have had relevance for studies of American politics. Collier and Messick's emphasis on decayFootnote 32 and Starr's work on the spread of the features of democracy,Footnote 33 while highly relevant to AP, have largely been ignored by Americanists. And, while Haas's study of transnational co-ordination across epistemic communitiesFootnote 34 and Mintrom's work on policy entrepreneurs in the American statesFootnote 35 present clear research synergies, these connections have yet to be made.

Similarly, the diversity in comparative politics can be seen through both a negative and a positive lens. On the negative side, without a common set of studies serving as a springboard, it may be harder to make sustained scholarly progress, increasing the likelihood of scholars continually reinventing the wheel. To our reading, for example, although Collier and Messick's pioneering study of the adoption of social security programmes systematically puts forth the idea that policy adoptions are driven not just internally, but also by the actions of other governments,Footnote 36 many subsequent studies have likewise claimed this insight as a new contribution. On the positive side, the lack of a core set of studies allows scholars more flexibility to veer off in new and exciting directions, often presenting ideas that are lacking in the AP and IR literatures. Thus, Simmons and Elkins, and also Weyland, have provided some of the more insightful and sustained analyses of the mechanisms by which policies have become more liberalized.Footnote 37 And Dolowitz demonstrates how the diffusion of rhetoric can precede the diffusion of policy adoptions.Footnote 38 In addition, although CP diffusion scholarship can certainly do more to draw on ideas from other subfields, Table 1 makes clear that, as a field, CP does considerably better than either IR or AP in drawing on the other subfields, with integration between CP and IR being particularly high (as in Figure 4).

Diffusion scholarship in international relations has not proceeded along a steady path, but instead consists of three loosely connected streams of literature – on the ‘contagion’ effects of war,Footnote 39 the international diffusion of norms,Footnote 40 and the role of power (coercion and incentive manipulation) among the causes of diffusion.Footnote 41 One might see this as a case of ‘splendid isolation’ rather than as a cause for concern: what can those who study the adoption of state lotteries or tobacco regulation policies learn from those who study the causes of war, or vice versa? However, there are a number of areas where insights are transferrable across fields and even where similar dynamics are at work. For example, race to the bottom (or top) dynamics operate both domestically and internationally, and international organizations may facilitate policy diffusion across countries just as federal governments do across states.

How can diffusion scholars avoid (or at least limit) redundancy and reap the benefits of bridge building? One valuable approach is to converge upon a common language and set of understandings for central concepts in diffusion studies. An overview of the literature reveals that scholars in different fields (and sometimes in the same field) use different terms to refer to essentially the same phenomenon. Language barriers can prevent communication and learning. For example, as shown above, despite clear connections between ‘diffusion’ and both ‘convergence’ or ‘race to the bottom’, scholarship using these latter two terms has become isolated from similar diffusion studies using different labels. Towards removing such barriers, a major goal of this essay is to suggest a common language that will enable the fields to move forwards and reach new common ground. Coupled with commonalities in the questions asked and agendas sustained, these three subfields can come together more fully, where appropriate, with mutual benefit. To start down this road, we now turn to an assessment of the who, what, when, where, how and why of policy diffusion.

Who Affects Policy Diffusion: Inside, Outside and In-between

Because diffusion studies focus on the policy of a particular government and how that policy relates to those found elsewhere, it may be too easy to forget that these policies are chosen by real people who have varying preferences, goals and capabilities. Indeed, numerous quantitative studies of policy diffusion have focused solely on the policies of governments and how they cluster geographically, but do so without any consideration of the actors involved in bringing these policies into being. And yet, without a focus on the policy makers themselves, studies of policy diffusion may miss important aspects of politics. In this section, we focus on three sets of actors: internal actors (i.e., those within the government that may be considering an innovation); external actors (i.e., those in the governments from which policies may diffuse); and go-betweens (i.e., those who act across multiple governments).Footnote 42

Internal Actors

Within potentially adopting polities, the actors who play significant roles in policy adoption are familiar to political scientists: the electorate, elected politicians, appointed bureaucrats, interest groups, and policy advocates, to name but a few.Footnote 43 These policy makers, coupled with their preferences, goals, capabilities and the environment in which they operate, are central to an understanding of diffusion.

The preferences of policy makers may be based on individual opinions and experiences or may be induced by the desires of the electorate, interest groups or others. Such preferences often affect the range of policy choices that policy makers consider, and therefore preferences influence the likelihood of any particular policy spreading from one government to the next.

Preferences provide an obvious starting point. But it is then necessary to turn to goals and capabilities, and to consider how the latter can constrain the attainment of the former. Broadly speaking, the goals of policy makers fall into two categories: political goals, such as re-election, reappointment, maintenance of power and appearing legitimate; and policy goals, such as adopting beneficial policies and attracting large tax bases.Footnote 44 Policy makers seeking the best policies are likely to seek out information about the policies found elsewhere.Footnote 45 Those with broader economic and budgetary concerns may see themselves in competition with other governments and may adopt policies to their own advantage.Footnote 46 And those needing to appear legitimate may adopt policies that are deemed appropriate by powerful leaders.Footnote 47

The capabilities of policy makers can affect the diffusion process in numerous ways. For example, American state legislators in ten states receive no salary for their services. Their legislatures are among the many that do not meet year-round and often do not have substantial staffs. Such ‘less professional’ legislatures produce different policies and respond differently to other governments than do more professional legislatures.Footnote 48 Likewise, policy experts in specific bureaucracies know many of the details of policies found elsewhere (and their likely impacts) than do generalists like elected politicians. These differences can affect the nature of policy diffusion.Footnote 49 Because of their limited time and information, policy makers may rely on cognitive shortcuts that affect the diffusion process and perhaps lead to poor policy choices.Footnote 50 These sorts of institutional constraints matter, but so does the broader political environment, acting as a constraint on whether politicians achieve their goals. Politicians likely to lose their next election, for example, may take on riskier policies. Interest group pressures may mount in unpredictable ways. And it may be necessary for citizens to change their opinions in order for policies to spread to a new state.Footnote 51 These factors often combine with the need or demand for policy change to form the ‘prerequisites’ for policy diffusion.Footnote 52

External Actors

The second group of relevant actors includes those in external governments, mainly those who have already adopted a policy. In most diffusion studies, these external actors are ignored, perhaps because they have already made their decisions. Yet neglecting these earlier decision makers may lead to a misunderstanding of the politics of policy diffusion. For example, in order to uncover evidence that earlier adopting governments influenced the subsequent decisions of governments adopting later, it is often important to know what caused these early adopters to innovate. Every new policy idea comes from somewhere, so to the extent that these first adopters acted without information or pressure from outside actors, researchers can be alerted to the causes of policy adoption that exist in the absence of diffusion, thereby minimizing the possibility of a spurious finding of diffusion.

In addition, features of these governments may influence the likelihood that others will follow their leads. Governments with more expertise, for example, may be seen as leaders and may be more likely to provide information to future adopters. Because potential adopters may be more likely to imitate large or wealthy governments,Footnote 53 and because these bigger and richer governments may have more success at creating norms that others are likely to follow, scholars need to be attentive to the features of external governments that increase or decrease the likelihood of diffusion.

Finally, these earlier adopters often do not just sit back and allow others to respond to their policy choices, but instead behave strategically and proactively.Footnote 54 For example, their business-friendly tax schemes may need to be adjusted if competition emerges. Their regulatory standards may be more effective if others adopt them as well. Their political aspirations may depend on demonstrating their policy's success to others. And their nuclear arms control doctrine's success may depend on the same doctrine being adopted by others.Footnote 55 In all of these circumstances, actors in one polity may wish to preempt, educate, coerce, or otherwise influence others.

Go-Betweens

The third group of relevant actors consists of those who are part of neither the government that is considering adoption nor the government that has already acted, but rather those who act as go-betweens. In hierarchical systems, top-down pressures add a vertical component to typical horizontal policy diffusion. Here, examples such as the US national government offering inducements to statesFootnote 56 or the European Union government seeking harmonization of policies across EU membersFootnote 57 offer a sense that actors at higher levels of government can influence policy diffusion through information provision or even coercion. Bottom-up vertical policy diffusion, such as from localities to states,Footnote 58 states to national governments,Footnote 59 or national governments to supranational governments,Footnote 60 also involves extensive go-between activities by key actors.

Although go-betweens may be elected officials, they need not be. Policy entrepreneurs, for example, advocate adoption not only within one government but also from one government to the next.Footnote 61 Epistemic communities organized around a particular policy area, sharing principled and causal beliefs, can profoundly influence policy diffusion, in part by facilitating learning.Footnote 62 Think tanks, academic entrepreneurs, research institutes,Footnote 63 mass media,Footnote 64 migrants,Footnote 65 and intergovernmental organizationsFootnote 66 all play significant roles in the spread of policies from one government to the next.

Studying each of these three types of actors and the interactions between them is crucial to a better understanding of the politics of policy diffusion. Early scholarship in American and comparative politics that ignored diffusion pressures often mischaracterized the policy making process. But early diffusion studies that set aside internal determinants of policy choices were also insufficient and potentially misleading. Scholarship combining internal determinants and diffusion pressures has become the norm in the literature today, with early leaders theoreticallyFootnote 67 and empiricallyFootnote 68 pointing the way (although often this work focuses only on internal policy makers, without much concern for external or go-between actors).

Yet, the degree of attention paid to different actors in diffusion studies varies substantially across fields of study. For example, Figures 2 and 4 above showed distinct clusters of scholarship on policy transfer, often country-specific studies that offer extensive details about the internal politics within such a country to determine whether and in what form the external policy was adopted. In contrast, much diffusion work capturing similar decisions across all states or numerous countries often lacks significant details of politics among internal actors. Indeed, many such works treat internal politics almost as a nuisance rather than as substantial in its own right. Diffusion scholarship offers the chance not only to explore how and why the policy actions of other governments and political actors influence the home government's policy choices, but also how politics within the home government can be better understood by considering which policy makers respond in which ways to other governments and their policies.

What Diffuses: Lotteries, War and Welfare

As Rogers illustrates, patterns of diffusion can be discerned across a fascinating range of areas, from water boiling practices in Peruvian villages to citrus eating in the British Navy.Footnote 69 Our focus here is specifically on the diffusion of policy innovations, and for the most part we have, therefore, set aside innovations outside of political science while still recognizing non-policy innovations that are central to political science, such as the spread of riots and coups,Footnote 70 governmental typesFootnote 71 and institutional structures.Footnote 72 While differences in the subjects of diffusion studies account for outlying clusters such as ‘Democracy’ for comparative politics but not American politics in Figure 2, or ‘War’ in IR in Figures 3 and 4, other topics like ‘Norms’ are relevant in American politics but are not well integrated into AP studies, as shown in Figure 3 above.

Even when one focuses solely on the spread of public policies, however, diffusion studies tend to ignore a wide range of relevant questions, including how ideas find their way onto the agenda, how agenda items become laws, whether laws are just ideas until an implementer turns them into actual policies, and so on.Footnote 73 This emphasis on stages of the policy process has long been central to public policy, yet the diffusion literature sets aside the early and later stages of the policy making process and focuses almost exclusively on the adoption stage.Footnote 74 Furthermore, studies usually have focused on first adoptions, and tend to characterize policies in a very simple, dichotomous fashion, such as states adopting lotteries,Footnote 75 or countries adopting specific gender equality policiesFootnote 76 or environmental standards.Footnote 77

These approaches have, of course, provided numerous insights. But scholars now need to look beyond adoptions, first innovations and dichotomous characterizations of policies. First, attention to other stages of the process – in particular, which issues arrive on the agenda in the first place, and how policies are implemented – seem just as likely to be subject to diffusion as innovations. Investigating these other stages thus promises to provide a more complete view of how policies move from one government to another. Secondly, there are often multiple adoptions within a specific policy area, a process obscured by looking only at first adoptions. An investigation of these later adoptions can be used to provide additional information about diffusion.Footnote 78 Thirdly, although treating adoptions as dichotomous choices may allow clean analyses, and may be appropriate in some cases, many policies come in multiple shapes and sizes. Analysing the scope of a policy change may be more important to understanding policy diffusion than studying the adoption of any policy within a broad area. Policies evolve and are reinvented as they spread in ways that shed light on the politics of policy diffusion,Footnote 79 with the comprehensiveness of some policies expanding as they spread.Footnote 80 The components of complex laws that seem to make them more effective are more likely to be chosen as policy modifications in other states.Footnote 81

Finally, in addition to examining components of single policies, returning to the simultaneous study of multiple policies (for example, the eighty-eight policies of Walker or the three distinct areas of GrayFootnote 82) would help uncover which processes are robust across different policy domains. Even within a single policy area, attributes such as a policy's complexity, its triability (i.e., the degree to which the policy can be tried on a limited basis), and its ability to be observed all appear to influence whether and how it diffuses.Footnote 83 Further, studies across policy domains may provide insight into which actors influence diffusion, and how such influence is exerted.

Mechanisms from A to Z: The How and Why of Diffusion

The standard (and quite broad) definition of policy diffusion – that one government's policy choices are influenced by the choices of others – leaves open for debate why policies spread and precisely how this diffusion comes about. Although a few studies have specified the mechanisms through which the authors contend diffusion is occurring, most rely on vague or implicit causal stories. Possible processes can perhaps be gleaned from the long list of colourful metaphors and modifiers found in the decades of diffusion studies: abandonment, acceptance, adaptation, adoption, amendment, avalanche, bandwagoning, best practices, billiard balls, borrowing, bottom-up, bubbling up, catalytic, change, clustering, coercion, communication, competition, contagion, cookie-cutter, co-operative, co-ordination, copying, convergence, cultural reference, decentralization, diffusion, divergence, disinhibition, emulation, enactment, experimentation, exporting, free-riding, Galton's problem, geographic, globalization, harmonization, hierarchical, horizontal, hybridization, imitation, importing, imposition, incentives, inducement, infection, innovation, insemination, inspiration, integration, interdependence, interstate, isomorphism, jumping, laboratories, laggards, leaders, leapfrogging, learning, lesson-drawing, linkages, localization, magnets, manipulation, mimicking, modelling, neighbours, networks, open method, peers, persuasion, pinching ideas, point source, pressure valve, prestige, problem solving, promotion, proneness, proximity, pruning, race to the bottom, reinforcement, reinvention, remodelling, S-curves, shaming, sharing, similarity, snowball, snowflakes, socialization, spatial, spread, success, synthesis, top-down, transfer, transitions, transnational, unification, vertical, voluntary, and whole-cloth.

Although it may be amusing to consider how snowflakes turn into snowballs and how shaming can become sharing, we believe that these 104 terms fundamentally capture, and thus can be reduced to, four main processes or mechanisms of policy diffusion.Footnote 84 These mechanisms are learning, competition, coercion and socialization.Footnote 85 For policy makers who seek to formulate effective public policies, learning from others is natural and expected. Learning is the process through which states act as laboratories of democracyFootnote 86 and through which decision makers seek to solve problems.Footnote 87 When a policy is effective and others learn about its success, diffusion naturally follows.Footnote 88 Learning, however, may be more complicated than simply discerning success. As we discussed above, actors in the potentially adopting government may have differing goals. Learning about policy effectiveness is all well and good, but policy makers may want to learn about more than effectiveness.Footnote 89 For example, policy makers may be concerned with learning about the policy's political viability and public attractiveness, about implications for re-election and reappointment, or about whether a glitzy modification of the policy could serve as a vehicle in the pursuit of higher office. Moreover, what makes a policy effective in one polity may have little applicability to its effectiveness elsewhere. While scholars often mention these considerations, systematic studies along these lines have yet to be conducted.

Furthermore, a view that is implicit in most studies is that if another government adopts a policy, learning will increase the likelihood that you will adopt it yourself. This may be true in most cases, but there are good reasons to suspect that there are exceptions.Footnote 90 First, as we detail later, diffusion may be contingent on a wide range of exogenous factors. Secondly, it is possible that the adoption of a policy in one country or state may actually decrease the likelihood of adoption in another for a host of reasons that extend beyond learning, such as if the adoption in one government leads to positive spillovers for a neighbouring government.Footnote 91 Thirdly, not all policies work. While there is evidence that failed policies might diffuse despite their objective lack of success,Footnote 92 it is also possible that earlier adoptions may prove to be unsuccessful, and other governments will learn either not to adopt these laws or to adopt them in radically different forms.Footnote 93

Governments not only learn from one another; they also compete. On the one hand, competition for tax bases, tourist revenue and attractive economic conditions more generally may be healthy, adding market discipline to government policy making.Footnote 94 On the other hand, competition across governments can be detrimental, possibly leading to trade wars,Footnote 95 difficult treaty negotiations,Footnote 96 and a ‘race to the bottom’ in the provision of redistributive goods.Footnote 97 Although learning can be accomplished with fairly passive external actors content with their early policy adoptions, competition tends to be characterized by robust and continuing strategic interactions among governments.Footnote 98

An even greater degree of interaction is involved in policy coercion, a process through which some actors attempt to impose their preferred policy solutions on a particular government. Coercion can be applied either vertically or horizontally. In the case of vertical coercion, actors who are not part either of the government that is considering adoption or of the government that has already acted can attempt to force their preferences onto the potential policy adopter. Domestically, the national government may fulfil this role, while supranational organizations may do so at the international level (e.g., if the European Union attempts to force member nations into selecting austerity measures). When acting in this way, the coercive actor can rely on the carrots and sticks of intergovernmental grants, regulations and the pre-emptive policies of a centralized government.Footnote 99

Coercion also can be accomplished in a horizontal setting, with one government applying pressure until the targeted government changes its policy;Footnote 100 thus, asymmetric power can be an important aspect of coercion in policy diffusion processes.Footnote 101 For example, external actors including powerful states or international organizations may attempt to influence the adoption of human rights policies in weaker countries through collaborative efforts such as sanctions,Footnote 102 or through issue linkage, making behaviour in one policy area contingent on behaviour in another.Footnote 103

Whereas coercive strategies aim to change governmental policies, socialization – ‘a process of inducting actors into the norms and rules of a community’Footnote 104 – can be used to change preferences. Although perhaps not immediately resulting in policy change, altered norms and preferences may lead to even more stable long-term policy change than coercion alone could achieve. For example, establishing one's self as an attractive and prominent leader, worthy of imitation, may improve one's ability to socialize. Countries possessing ‘soft power’ can attract others by setting an example, making coercion an unnecessary option.Footnote 105

As noted earlier and illustrated in Figure 3, the roles of norms and preference change are most fully developed in the IR and comparative literatures. Ironically, however, this concept (as it applies to diffusion) originates in the American politics literature, with Walker.Footnote 106 Since then, however, it has largely been missing from studies of diffusion in the United States. In comparative politics, an early use of this idea can be found in Collier and Messick, who note the status-seeking involved in the social security decisions of late adopters.Footnote 107 Still, the role of socialization in diffusion was not fully developed until the constructivist turn in IR emphasized the importance of ideas and norms for understanding international politics.Footnote 108 For example, epistemic communities of policy experts can facilitate the diffusion of norms.Footnote 109 Internal actors, however, are not simply passive in this socialization process, as norms can be rejected or adapted to local conditions.Footnote 110 In addition, rhetoric and ideology are key components of socialization, which ultimately may determine which policies diffuse.Footnote 111

With these four mechanisms in mind, the role of actors in policy diffusion comes into sharper focus. For example, although diffusion is often thought to be a horizontal process (or a bubbling up from below), consider the vertical nature of go-between actors affecting the spread of policies. National policy makers or intergovernmental organizations in federal systems, as well as international organizations, may serve a vertical role in policy diffusion through multiple mechanisms. Such centralized actors can facilitate learning or engage in socialization through the establishment of information clearinghouses, holding conferences or suggesting best practices.Footnote 112 They may play a coercive role, with grant and aid conditions, pre-emptive laws, sanctions regimes or use of military force. They may help restructure competitive environments, such as with the European Union facilitating the reduction of trade barriers or the US Constitution limiting interstate regulation of commerce by the states. Precisely when external and go-between actors (as well as the internal actors themselves) utilize each of these mechanisms, and to what ends, has not been studied systematically, but is ripe for future exploration.

Because these mechanisms had not been made explicit throughout much of the history of policy diffusion scholarship, most examinations of diffusion proceeded without much theoretical grounding. Most commonly, especially in the American politics literature, diffusion scholars looked at clusters of geographic neighbours. Although this was useful both to document the existence of diffusion and to suggest possible pathways, neighbourhood effects unfortunately do little to isolate the politics behind policy diffusion. For example, neighbours compete with one another, learn from one another, coerce one another and socialize one another. Moreover, neighbourhood adoption patterns that appear to be a function of interdependence instead may occur because these neighbouring polities face similar policy problems at about the same time. A focus on similarities other than geography, like race,Footnote 113 ideology,Footnote 114 budgets,Footnote 115 or religion, language and culture,Footnote 116 may provide greater insights. And yet these similarities, if not examined with a systematic understanding of the mechanisms and politics of diffusion, may likewise shed little new light on the diffusion process. Similar polities, whether neighbours or not, may adopt similar policies irrespective of their interactions with one another.Footnote 117

It may be possible to separate these mechanisms from one another in order to determine when each is relevant for particular policies across specific governments. Yet doing so requires sophistication in both theoretical understandings and empirical strategies. Some theoretical underpinnings that may allow scholars to discern diffusion mechanisms from one another range from the work of Leichter a quarter century ago to the recent directions of Simmons, Dobbin and Garrett.Footnote 118 Empirically, Boehmke and Witmer disentangle the diffusion processes of the initial adoption (learning) or expansion (competition) of American Indian gaming compacts, illustrating that learning from one’s own past practices substitutes for learning from others.Footnote 119 Shipan and Volden demonstrate that multiple mechanisms account for the diffusion of local anti-smoking policies in the United States.Footnote 120

Although such approaches all show promise, a key challenge for quantitative researchers across subfields lies in operationalization. Better indicators must be developed to match the theoretical concepts underpinning the diffusion mechanisms. Thus far, progress often has been limited to indicators that rule out some mechanisms and, therefore, serve as proxies by default for other mechanisms. For example, in their study of US state lotteries, Berry and Baybeck capture the close geographic proximity needed for competition, and thus regard any additional diffusion evidence as ‘learning’.Footnote 121 Other scholars have labelled the enhanced spread of successful policies as learning, largely because policy success is not necessarily central to competition, coercion or socialization. While this is a reasonable approach, the diffusion of successful policies serves only as a proxy for learning, rather than as a direct measure of learning itself. While progress has clearly been made in identifying mechanisms theoretically and in initial empirical assessments, major challenges in operationalization remain. Scholars across subfields should be observant of one another's achievements in this area and should themselves help any such advances diffuse across subfield boundaries.

Complicating this progress even further, diffusion mechanisms are often interrelated.Footnote 122 For example, governments may learn about how to compete with one another better.Footnote 123 As another example of interrelated diffusion mechanisms, an international organization might try to use socialization and learning mechanisms at the same time in order to change both beliefs and behaviour. Changing norms may be a precursor to policy change. And governments in competition with one another may wish to exert coercive influence when possible. Thus the mechanisms discussed here may be complements rather than substitutes, at least under certain conditions that scholars need to identify. Those attempting to disentangle one mechanism from another should not concentrate only on independent effects when interdependent effects are both more interesting and more realistic.

Exploration of the mechanisms of diffusion offers one opportunity for greater integration between qualitative and quantitative scholarship. In our view, two of the most fruitful qualitative–quantitative interactions are found just prior to and just after quantitative analyses. First, the development of hypotheses to be tested cannot be done in a vacuum. Without clear and well-founded facts on the ground, often best provided through qualitative research, quantitative scholars have an insufficient understanding of the relevant politics to produce ultimately fruitful analyses. Secondly, quantitative research is always limited by what can be measured and often leaves readers with a better sense of what is happening politically than why it is happening. Such limitations offer a further opportunity for qualitative work designed to overcome data limitations carefully and to explore causal processes. With respect to diffusion mechanisms, the quantitative studies noted above would not have been nearly as successful without the qualitative groundwork that detailed the many policy interactions among governments. And we are now at a point where qualitative research could nicely complement quantitative analyses, such as with fuller assessments of what exactly policy makers seek to learn from othersFootnote 124 or how socialization comes about.Footnote 125

Qualitative and quantitative collaborations may also be productive given the normative connotations associated with aspects of policy diffusion. Learning, for example, is often thought to be quite positive – and yet learning processes need not always result in the most appropriate policy choices.Footnote 126 Coercion is mainly seen in a negative light, but it can help reluctant politicians rise out of an equilibrium of corrupt and costly practices, perhaps even with an active choice to bind their own hands. Competitive pressures promote efficiency, even at the cost of equity. And the benefits or costs of socialization depend on one's perspective, where the socialized and the socializing may hold different views.

Although it may be reasonable to leave such normative considerations aside in positive scholarly endeavours, such considerations may be of use to policy practitioners. For example, devolution of policy control within federal systems often rests on an implicit view of policy diffusion. Allowing states and localities to formulate their own policies may lead not only to experimentation and learning, but also to competition, socialization and even coercion.Footnote 127 Intervention by the national government may facilitate information flows or may coerce subnational governments to avoid the most detrimental of competitive practices. For example, devolution of US welfare policies to the state governments in the 1990s encouraged experimentation and learning, while at the same time limiting competitive race-to-the-bottom pressures through coercive grant conditions that mandated the maintenance of effort in welfare payments. Along similar lines, policy makers within countries and international organizations seeking to improve the world through their influence over the choices of others may benefit from understanding which mechanisms have which effects on policy outcomes.

Conditional Nature of Diffusion: When and Where

We believe that the most exciting and informative research on policy diffusion today asks not simply whether policies are diffusing and who is involved in those processes; rather, the future of policy diffusion research lies in uncovering the whens and wheres. Intriguingly, there appears to be a divide between studies of the process of diffusion and those of the destinations of those processes. Thus, Figures 2 and 3 show ‘race to the bottom’ and ‘convergence’ scholarship as distinct from other diffusion work both within American politics and outside of that subfield. What is different about such studies is their focus on the direction and possible endpoint (to which they are racing or converging) of diffusion processes, rather than on the processes themselves. Yet because their approaches and findings so closely relate to other diffusion scholarship, these works easily could be more fully integrated into the heart of diffusion scholarship.Footnote 128

Setting aside the destination, diffusion processes themselves are quite complicated, with effects that are difficult to discern coherently from one study to the next. As we have detailed, a broad array of actors, different types of policies and multiple mechanisms all set the stage for a complex play of potentially triumphant or tragic choices. Having been convinced that policy choices across governments are interrelated, scholars have found sparks of insights about the conditional nature of policy diffusion but have yet to illuminate a systematic path forward. We know, for example, that not all policy makers pay equal heed to the policies of one another. We know that not all policies spread in the same manner, and we know that not all mechanisms are at work in the spread of all policies. Yet the studies that demonstrate these things usually offer an illustrative example, rather than a level of understanding that can be transplanted from one situation to the next. Future work needs to discern systematic patterns in the conditional nature of diffusion.

The characteristics of internal actors, for example, seem to play a significant role in which policies spread in what manner. Examples abound. Füglister, for example, shows that joint membership in intergovernmental health policy bodies is related to the diffusion of successful policies.Footnote 129 Kelemen and Sibbitt similarly illustrate how economic liberalization and political fragmentization affect the spread of the American legal style around the world.Footnote 130 Shipan and Volden show that state legislative professionalism and interest group activism are crucial for anti-smoking policies to diffuse from US cities to states.Footnote 131 Milner finds that autocratic governments are less likely to embrace the diffusion of internet technologies than are democracies.Footnote 132 Checkel argues that the effective diffusion of norms via socialization depends on whether the decision-making processes within European countries are top-down with elites adopting norms first or bottom-up with the masses or groups changing their norms first.Footnote 133 Methodologically, Neumayer and Plumper offer an approach to incorporating such conditional effects into quantitative empirical analyses.Footnote 134

The nature of external actors is also important to understanding when and where policies spread. The classic works of Crain and Walker illustrate that some governments are seen as leaders, due to their size, wealth and cosmopolitan nature.Footnote 135 Such leader governments may be tapped more frequently for policy ideas than less innovative governments, and may also be better able to socialize others successfully. Similarly, the go-betweens of policy entrepreneurs and epistemic communities influence when and where policies spread. In many of these studies, however, the conditional nature of the diffusion process was not uncovered as fully as it could have been. For example, numerous scholars have found that the presence of policy advocates affects the likelihood of the adoption of a particular innovation.Footnote 136 Yet these analyses did not test the interaction of the existence of advocates with a geographic neighbours variable (or with variables capturing other mechanisms of diffusion). Thus, while the polities with such crucial advocates were more likely to adopt innovative policies, we do not know, for example, whether advocates substitute for a learning process or reinforce such processes.

Moreover, in addition to looking at how each of these crucial actors interacts with diffusion mechanisms, it is important for future scholars to explore the interactions among these different actors. For example, Stone suggests that external or go-between actors are better able to engage in coercion and socialization when internal actors are reeling from a defeat in war or an economic crisis.Footnote 137 Bailey and Rom show that competitive pressures in redistributive policy making are limited to those governments that are already more generous than their peers.Footnote 138 Prakash and Potoski, as well as Zeng and Eastin, illustrate how standards among trading partners may lead to a race to the top in environmental practices.Footnote 139 The existence and nature of the linkages among internal, external and go-between actors may influence which diffusion mechanisms are used. Finnemore, for example, argues that the adoption of particular science policies depended on the interactions between UNESCO officials and national-level politicians in developing countries.Footnote 140 And Drezner notes how policy convergence (presumably through coercion and socialization) turns into competition when great powers disagree over policies and political goals.Footnote 141

In addition to the conditional nature of policy diffusion based on who is involved and on what is being adopted, the when of policy choice also has some subtle effects on the spread of policies across governments. In uncovering the innovativeness of different states, Walker implies that there is something fundamentally different about leaders, middle adopters and laggards, and perhaps about how policies spread across these temporally segmented sets of governments.Footnote 142 Canon and Baum similarly find some states to be earlier adopters, but also note that the speed of diffusion has changed over the decades their study examines, perhaps with learning or other mechanisms becoming more available, influential and timely in recent years.Footnote 143 The speed of adoption likewise is definitionally related to the S-curves associated with diffusion in non-regional models of diffusion.Footnote 144 Surprisingly, however, despite the discussion of speed in these earlier studies, very little recent scholarship has examined the factors that affect the rates at which policies diffuse.Footnote 145

Another relatively unexplored possibility is that where one looks temporally in the diffusion process may influence what one finds. Numerous studies support this argument. For example, Welch and Thompson find that coercion becomes more important later in the process; Mooney finds that competition matters more early on; Gilardi, Füglister and Luyet provide evidence that learning increases over time, as knowledge accumulates.Footnote 146 Moreover, Mintrom and Vergari illustrate what can be missed by focusing only on the later adoption stage of the policy process, as they find that external networks of experts and geographic neighbours were relevant in explaining the initial consideration of education reform but not their subsequent adoption.Footnote 147

Most of these conditional diffusion patterns, whether dependent on the actors, the policies or the stage in the diffusion process, were uncovered one at a time through careful but perhaps not generalizable empirical studies. As the scholarship on policy diffusion moves forwards, it would be valuable to have a more systematic grounding in theory in order to structure the empirical work around broad and hopefully general claims. Given the complex and conditional nature of policy diffusion itself, it is perhaps unsurprising that rather complex diffusion patterns emerge from such preliminary theoretical works.Footnote 148 Volden, Ting and Carpenter find, for example, many similarities between independent adoptions and learning across governments, but also isolate conditions (based on free-riding behaviour and differing learning opportunities) under which learning effects can be isolated.Footnote 149 Game theoretic models or systematic claims arising from non-mathematical theorizing also would benefit from incorporating the other mechanisms of diffusion, as well as a more complete set of political actors. Indeed, theoretical and empirical advancements must proceed hand in hand, with new empirical findings informing theoretical developments that are in turn subject to empirical scrutiny. Such a scientific process for studying policy diffusion can be far more transparent and explicit than it has been in the past.

Learning from One Another?

Just as governments might learn from one another and facilitate policy diffusion, so too should political scientists working in different subfields learn from one another in order to facilitate the diffusion of useful tools and ideas in their studies. Different substantive emphases or methodological commitments may direct attention towards a certain set of hypotheses and away from others. Though different fields may have reasonable explanations for their respective areas of focus – for example, power in international relations or legislative committees in American politics – it is nevertheless useful to look across subfield lines to see what is being tried elsewhere and to think about how it might apply in one's own work. Similar types of actors affect policy adoption regardless of the geographic unit, whether cities, states, countries or intergovernmental organizations. The mechanisms of learning, competition, socialization and coercion remain relevant across these units as well, as do both vertical and horizontal diffusion dynamics.

Yet, with few exceptions, the policy diffusion literature has developed separately, if concurrently, in comparative politics, American politics and international relations. If communities of scholarship ideally retain both coherence and openness, the network analysis undertaken above shows that although each subfield has its strengths, none is demonstrative of an ideal balance. Comparative scholarship appears to have a high degree of openness, drawing frequently from both AP and IR scholarship. At the same time, however, it is difficult to assess progress, as convergence around a set of core research questions is lacking. American politics appears to suffer the reverse ailment: scholarship draws more sparingly from the other fields, yet we see some coherence in the research programme, with early work producing stylized facts, and later work seeking to explain variation. With the new emphasis on mechanisms, both AP and CP research is beginning to test competing hypotheses of diffusion, though this work remains in its very early stages. IR scholarship seems to fall somewhere between the others, fostering separate communities in diffusion scholarship that make progress on their own, but which are somewhat isolated from others.

We suggest that each subfield will be better off by being both more coherent and more open. Coherence calls on scholars to address a core set of research questions, to take into account past work and to attempt to improve upon it, aiming towards producing a better understanding of the causes of policy diffusion across time and space. Openness will facilitate this better understanding by alerting scholars to relevant concepts, actors, mechanisms and research strategies that may be useful in the endeavour.Footnote 150

Throughout this study, we have raised numerous ideas for future research that we believe will be particularly fruitful. We conclude not with a restatement of these directions, but rather with three ways in which diffusion scholarship across the fields of political science could become more fully integrated with mutual benefits. First, a mere awareness of the related work being done by scholars across fields may spur new ideas, synergies and collaborative projects in the future. We have tried to highlight many such connections in the citations and topics explored above. Secondly, a common language of diffusion scholarship would be helpful. For example, rather than adding another diffusion metaphor to our list of more than a hundred terms, we should reflect on whether the processes we are studying fit nicely into the categories of learning, competition, coercion or socialization. By clearly labelling the mechanisms we study, we open our work up to more natural comparisons to similar studies elsewhere. Not only should scholars use common terms for diffusion mechanisms, but also for specific types of actors (internal, external and go-betweens) and policies (on such dimensions as their complexity, and the possibility of testing or observing them).

Finally, whereas any individual scholar may be overwhelmed by the many areas for future research that we discuss, the collective scholarly community is well suited to take on these tasks. As with any substantial and advanced field of study, further insights can be gained by the field embracing both micro and macro levels of analysis simultaneously, through both specialization and aggregation. In terms of specialization, for example, scholars who know a particular policy area extremely well and can tease out the central actors or the exact diffusion mechanisms dominant in that area would add crucial building blocks.

At the same time, aggregation is critical. Where such earlier individual studies can be well categorized in terms of actors involved, mechanisms uncovered, and policies investigated, larger systematic patterns may come into focus. We may find, for example, that go-betweens in learning-based diffusion vary between policies that can be easily tried and abandoned as opposed to those that are more fixed upon adoption. And such go-betweens may serve quite different roles for similar policies spreading through coercion or socialization. Alternatively, the capacity of policy makers may be a crucial determinant in the spread of highly complex policies, but largely inconsequential for diffusion of less complicated policies. As a healthy and robust field of study, policy diffusion research can thus build upon the disparate interests and strengths of all its scholars, illustrating the benefits of an integrated and collaborative approach to political science.