Democratic states place a variety of demands or expectations on citizens. Some, such as voting, are entirely voluntary in most democracies. Others, such as paying taxes, are legally enforced, but the impossibility of universal monitoring means that even such demands rely on ‘quasi-voluntary compliance’ when no one is watching.Footnote 1 Thus, citizen compliance in democracies – ‘the process of complying to a desire, command, proposal, or regimen’Footnote 2 – includes obeying the law, but also fulfilling political roles or expectations that contribute to the democratic process in the absence of formal coercion. This voluntary willingness of citizens to engage in state affairs has long been seen as a hallmark of well-functioning democracies.Footnote 3

Yet why do many citizens comply in democracies, when doing so is often costly and coercion is limited? Conventional wisdom is that they do so because of expected payoffs. Compliance incurs immediate costs, but those are often outweighed by long-term or non-instrumental benefits that individuals also care about, such as expressive or psychic incentives, group interests or even fairness.Footnote 4 Other times, strong penalties or strict monitoring make the potential costs of non-compliance higher than that of compliance.Footnote 5 Either way, the common logic is that citizens choose to comply when they see it as net beneficial to do so, although what counts as a benefit may vary across individuals.

Payoff concerns are very real, but I argue that, taken alone, they miss an equally important, communal aspect of democratic compliance. This article finds that many individuals are also willing to comply out of an ethical obligation to their nations. That certain group memberships have the power to instill an intrinsic sense of duty to the group, even in the absence of coercion, has long been recognized.Footnote 6 Yet surprisingly little is known about the scope of such groups, the conditions under which their ethical capacity is politicized and to what consequence for democratic politics.

The contribution of this article is two-fold. First, it demonstrates that, for many, the nation is a special community that exerts real ethical pull. Second, it identifies the conditions under which such ethical ties to the nation motivate a willingness to comply with the democratic state. I argue that feelings of obligation to the nation become politicized in support of compliance when the identities of the state and ‘my’ nation are closely linked. In such cases, the welfare of one’s national community and that of the state are seen as intimately related, so that the needs or demands of that state invoke an ethical obligation to comply – a sense of citizen duty. Such linkages are often the result of historically specific critical junctures. But once solidified, I show that they serve as a powerful, ethical lens through which democratic compliance is understood.

I test the theory through a two-level design that combines case selection with mixed methods. South Korea and Taiwan are chosen as most similar cases that contrast in the degree of nation-state linkage – the unexpected result of divergent nationalist movements prior to democratization. South Korea evolved to have strong nation-state linkage for most, while this linkage remains fractured or weak for many in Taiwan. Despite impressive structural and political similarities, the pairing therefore yields divergent predictions on the power of national obligation to motivate a citizen duty to comply. Across both cases, statistical modeling and paired experiments are combined to carefully identify this ethical pathway and demonstrate its predictable presence (and absence) behind citizen duty towards voting and other forms of democratic compliance.

Together, the findings provide a more diversified picture of why citizens choose to comply in democracies. For many individuals, the willingness to comply appears to be as much about who they are as a national community, as it is about give-and-take with the state. In fact, for individuals who see compliance primarily through the lens of national obligation, the data show that payoff concerns matter little to none. These findings have implications for a variety of policies designed to increase political engagement or instill citizen responsibility in new or marginalized citizens. They also provide an empirical counterpoint to the dominant assumption that strong nationalism and sticky group attachments in general – often associated with negative outcomes such as blind obedience, intolerance and xenophobia – are a hindrance to liberal democracies. Instead, the findings demonstrate an unexpected way in which ethical ties to the nation contribute to a central phenomenon in healthy democracies.

NATION, DUTY AND COMPLIANCE

Individuals are citizens of a state, but also belong to various communities. Some of these communities are special in that many individuals come to perceive them as an integral, as if natural, part of their identities. Communitarian political theorists have long recognized such memberships to be ethically charged.Footnote 7 That is, they are able to instill a sense of ethical obligation to the group’s welfare, even in the absence of coercion or incentives.Footnote 8 As Sandel argues, ‘to some I owe more than justice requires or even permits … in virtue of those more or less enduring attachments and commitments that, taken together, partly define the person that I am’.Footnote 9

Ethical obligation to the group is different from the pursuit of group interests or group status in that it is an intrinsic commitment. Take for example family, a special community for many individuals. When family is in need of help, individuals often respond out of a sense of duty. That is, they do so because they believe it is the right thing to do as a member of that family, not because their action will necessarily advance the family interest or status. Of course, sometimes it can. But what distinguishes ethically motivated individuals is that they would respond even when such odds are very low.

I argue that, for many individuals, the nation is one such special community. The nation is an ‘imagined community’Footnote 10 of people who, for one reason or another, see themselves to share a common legacy and future.Footnote 11 In many established democracies, national membership is socialized so as to feel like a natural part of one’s identity in a world of nations.Footnote 12 As Billig notes, ‘this reminding is so familiar, so continual, that it is not consciously registered as reminding’.Footnote 13 Certain theorists have argued that this perceived naturalness in national membership grants it significant ethical pull.Footnote 14 Nations may be the constructs of states and political elites,Footnote 15 but once solidified and internalized, the claim here is that they exert an ethical force of their own.

When and why do ethical ties to the nation become politicized towards compliance with the state? I argue that such politicization depends on how one’s national community is embedded vis-à-vis the state under which ones lives. The conditional logic is as follows. When the state is seen to represent ‘my’ nation, national welfare becomes closely tied with that of the state. In such cases, acts of citizen compliance contribute not only to the welfare of the state, but also my nation. Then for individuals who feel an obligation to the nation, this linkage invokes an ethical frame towards compliance and motivates a sense of citizen duty to comply. Alternatively, when the state is seen as representing a national ‘other’, national obligation should play little to no role in motivating a citizen duty to comply. In fact, when the state is seen as threatening to the welfare of one’s nation, national obligation should motivate a political duty to actively resist complying with the state.

This is not a vague theory about patriotic passions or blind collectivism. Depending on the political context, we expect the capacity of national identity to invoke an ethical frame towards compliance to vary predictably. The rest of the article turns to empirically assessing this ethical pathway.

EMPIRICAL STRATEGY

Does an obligation to the nation motivate a citizen duty to comply with the state? The question faces two kinds of empirical challenges. At the macro-level, various critical junctures, structural endowments, or aspects of the state can drive both national obligation and citizen duty at the same time. At the micro-level, how to identify an ethical obligation – an intrinsic commitment – and distinguish it from other motivations to comply that are also rooted in national identity, is not obvious.

I use a two-level design that simultaneously leverages case selection and mixed methods to address these challenges. The first level selects comparison cases that naturally control for as many macro-level confounders as possible, but still contrast on the key condition that activates an ethical frame towards compliance. The logic is that if the effect of national obligation on a citizen duty to comply is real, and not an artifact of particular historical or structural factors, then it should vary predictably across the two cases despite their macro-level similarities.

The second level employs two complementary methods across both cases to identify the micro-level mechanism. To start, a statistical model that can proxy the presence (and absence) of an ethical obligation to the nation is derived and tested on national surveys. This is followed by a pair of experiments that explicitly prime national obligation as the motivation for citizen duty in both places. In South Korea, the treatment was embedded in a turnout field experiment in a mobile election; in Taiwan, it was placed in a survey experiment on voluntary compliance in the event of a state crisis. The specific treatment is tailored to each context, but the same substantive prime is essentially replicated across two different settings of nation-state linkage.

This design allows cross-case comparisons within a method, as well as cross-method comparisons within a case. No single component of this design is novel, but conjointly, they triangulate towards a causal claim by baking in both internal and external validity checks.

THE SETTING

Only about 1,500 kilometers apart, South Korea and Taiwan share an impressive number of similarities: both democracies were colonized by Japan in the early twentieth century, endured a phase of military authoritarianism after independence, democratized from below, developed rapidly in the 1980s, are racially homogeneous, and are cultural strongholds of Confucianism.Footnote 16 Both have relatively high levels of citizen engagement, with higher electoral turnout than most advanced Western democracies and healthy protest cultures. Despite these similarities, different nationalist strategies prior to democratization resulted in contrasting nation-state linkages under the surface.

South Korea is widely perceived as an ethnic nation-state, with strong linkage for most citizens. This is largely the result of how Korean national identity was ‘racialized’ during Japanese colonialism (Cumings Reference Cumings1984). Against the Japanese, who ruled on the basis of racial supremacy, Korean nationalist leaders sought to emphasize the distinctiveness of the Korean race. Even if not politically autonomous, the nation would continue by maintaining a pure bloodline.Footnote 17 As prominent nationalist leader Yi Kwangsu stated in A Theory of the Korean Nation: ‘Koreans cannot but be Koreans … even when they use the language of a foreign nation, wear its clothes and follow its customs in order to become non-Korean’.Footnote 18 Hence, there is little doubt among South Koreans that the state cannot represent any other nation, with most perceiving strong nation-state linkage based on shared ethnicity.

In contrast, a different nationalist strategy has rendered Taiwan a ‘divided society’.Footnote 19 Japanese colonialism left a very different imprint on Taiwan than it did in Korea. Under Japanese rule, the island went from a haphazardly ruled periphery of the Qing dynasty, with little sense of unity among the various settlers from China and native aborigines,Footnote 20 to a more integrated, centrally managed community with a large educated class.Footnote 21 The shared experience of colonialism forged a shared sense of islander identity, and importantly, set the stage for the relative disdain many would feel towards their new rulers from mainland China.

The return to Chinese rule after World War II proved to be a ‘recolonization rather than decolonization’ for many islanders.Footnote 22 The Kuomintang (KMT) military from mainland China often treated the islanders as second-class citizens, with tensions culminating in an islander massacre in the ‘2-28 Incident’.Footnote 23 With the ultimate goal of reclaiming the mainland, the KMT began an aggressive re-Sinicization of the island, invalidating all islander dialects, customs and history. Mainland Chinese culture was made ‘a kind of totalizing force in so far as its fate was perceived to be synonymous with the national destiny itself’.Footnote 24

Yet KMT efforts backfired. The forced imposition of a Chinese national identity that had grown distant from generations of separation from the mainland ‘ended up emphasizing, rather than muting, the differences between [the KMT’s] view of culture and that of the Taiwanese’.Footnote 25 The stirrings of a uniquely Taiwanese national identity, as separate from China both culturally and politically, gained momentum and served as the basis for the opposition Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) after democratization. Thus, national identity remains deeply contested on the island (Chang and Wang Reference Chang and Wang2005). The majority of citizens, who are of islander descent and believe Taiwan to be separate from China, tend to identify as Taiwan nationalists. The minority, who are of mainlander of descent and believe Taiwan to be a part of China, mostly identify as China nationalists. Finally, many youth identify as New Taiwanese (xin Taiwanren) – the effort of political elites from both sides to move past ethnic tensions and reimagine Taiwan as a civic, democratic nation.Footnote 26

Which national community does the state represent? Electorally, the KMT has held the presidency for longer periods and was in power at the time of data collection. But also in a deeper sense, the legacy of the KMT’s nationalist indoctrination of the state apparatus still casts a long shadow.Footnote 27 For example, regarding the military, former Defense Minister Andrew Yang explains:

[This] is a national armed force. It doesn’t serve any political party. But ordinary citizens still get this idea that the armed forces is in favor of [the KMT], because you have a long history of the military, party, and country being unified as one entity. So they still have this impression.Footnote 28

Thus, unlike in South Korea, nation-state linkages are mostly weak in Taiwan. For self-identified Taiwan nationalists, the KMT-rooted state does not represent ‘my’ nation. Linkage is similarly weak for New Taiwanese. If Taiwan is a democratic nation, then it should be independent from non-democratic China. But since the KMT fundamentally opposes independence, the state cannot fully represent this civic identity. The only group for whom nation-state linkage is strong is the minority of China nationalists.

South Korea and Taiwan therefore make one of the strongest naturally controlled pairings for this study. Despite impressive similarities in the formative and structural aspects of the democratic state, the theory predicts that national obligation should play a significant role in motivating citizen duty towards compliance in South Korea, but not in Taiwan. The Taiwanese case also enables a subnational test. Given the different nation-state linkages across the national identity groups, the effect of national identification should vary even within the same state. While the effect should be negligible for Taiwan nationalists and New Taiwanese, for China nationalists only, we should see patterns similar to South Korea. This subnational test mitigates concerns that any cross-country variation is driven by some unobserved difference between the two states.

FINDINGS

The primary challenge in identifying an ethical obligation to the nation as a reason to comply is that intrinsic commitments are not directly observable.Footnote 29 In order to show that this ethical pathway is real, I therefore triangulate through a combination statistical modeling of survey data and experimental priming.

Survey Evidence

Identification

In the survey data, I use strength of national identification as an observable proxy for national obligation. By national identification, I refer to both group membership and a psychological attachment to that identity – what Huddy and Khatib characterize as an ‘internalized sense of belonging’Footnote 30 to the nation. Across communitarian theory, social identity theory and group mobilization studies, it is precisely this subjective attachment that serves as the source of commitment to the group and provides the impetus to take action on its behalf.Footnote 31 Not all individuals who identify with their nation will feel an obligation to it, but the assumption is that the reverse is highly improbable and that strength of obligation increases monotonically with identification.

The surveys test two observable predictions from the theory. The most obvious is that, where nation-state linkage is strong, national identification should be positively related to citizen duty to comply with the state. The second prediction comes from a unique property of obligation. In moral philosophy, Kant famously argued that what distinguishes obligation from other motivations is its principled nature:

A good will is good not because of what it accomplishes or effects, not by its aptness for the attainment of some proposed end, but simply by virtue of volition – that is, it is good in itself.Footnote 32

In other words, the presence of an ethical obligation should compel the individual to act irrespective of the payoffs from the action. Only when an ethical obligation is absent should she turn to assessing the payoffs. This ordinal sequence between ethical versus non-ethical considerations can be modeled as a lexicographic decision rule with two dimensions.Footnote 33 Application to the present context is as follows:

$${\rm Pr}\left( {Y_{i} {\,\equals\,}1} \right) {\,\equals\,} {\rm Pr}\left( {d_{i} {\,\equals\,}1} \right) {\plus} {\rm Pr}\left( {d_{i} {\,\equals\,}0 \,\&\, b_{i} \geq 0} \right) $$

$${\rm Pr}\left( {Y_{i} {\,\equals\,}1} \right) {\,\equals\,} {\rm Pr}\left( {d_{i} {\,\equals\,}1} \right) {\plus} {\rm Pr}\left( {d_{i} {\,\equals\,}0 \,\&\, b_{i} \geq 0} \right) $$Individual i has a citizen duty to the state (Y i=1) when she feels an ethical obligation to her nation (d i), or despite no national obligation, expects net positive benefits, b i. Since individuals are not always black and white about obligations in practice, I model obligation as a continuous probability instead. Assuming independence between the probabilities, Equation (1) can be rewritten as follows:

$${\rm Pr}\left( {Y_{i} } \right){\,\equals\,}{\rm Pr}\left( {d_{i} } \right){\plus} \left[ {1{\minus}{\rm Pr}\left( {d_{i} } \right)} \right]{\asterisk}{\rm Pr}\left( { b_{i} \geq 0} \right)$$

$${\rm Pr}\left( {Y_{i} } \right){\,\equals\,}{\rm Pr}\left( {d_{i} } \right){\plus} \left[ {1{\minus}{\rm Pr}\left( {d_{i} } \right)} \right]{\asterisk}{\rm Pr}\left( { b_{i} \geq 0} \right)$$ The components of Equation (2) can then be expressed as conditional probabilities given the observed estimates  $\hat{d} $ and

$\hat{d} $ and  $\hat{b}$ of the true values. I use the following linear approximations:

$\hat{b}$ of the true values. I use the following linear approximations:  $\Pr \left( {d_{i} \,\mid\,\hat{d}_{i} } \right){\,\equals\,} \alpha _{d} {\plus}\beta _{d} \hat{d}_{i} $, where

$\Pr \left( {d_{i} \,\mid\,\hat{d}_{i} } \right){\,\equals\,} \alpha _{d} {\plus}\beta _{d} \hat{d}_{i} $, where  $\hat{d}_{i} $ is the observed strength of national identification, and

$\hat{d}_{i} $ is the observed strength of national identification, and  $\Pr \left( {b_{i} \geq 0{\rm \,\mid\,}\hat{b}_{i} } \right){\,\equals\,}\alpha _{b} {\plus}\beta _{b} \hat{b}_{i} $, where

$\Pr \left( {b_{i} \geq 0{\rm \,\mid\,}\hat{b}_{i} } \right){\,\equals\,}\alpha _{b} {\plus}\beta _{b} \hat{b}_{i} $, where  $\hat{b}_{i} $ is the observed measure of payoffs. Substituting these approximations into Equation (2) and multiplying out gives the following:

$\hat{b}_{i} $ is the observed measure of payoffs. Substituting these approximations into Equation (2) and multiplying out gives the following:

$$\eqalignno{ \Pr\left( {Y_{i} \,\mid\,\widehat{{d, }} \hat{b}} \right) & {\equals} \Pr \left( {d_{i} \,\mid\,\hat{d}_{i} } \right){\plus} \left[ {1{\minus}\Pr \left( {d_{i} \,\mid\,\hat{d}_{i} } \right)} \right]{\asterisk}\Pr \left( {b_{i} \geq 0{\rm \,\mid\,}\hat{b}_{i} } \right) \cr & {\equals} \ \alpha _{d} {\plus}\beta _{d} \hat{d}_{i} {\plus}\alpha _{b} {\plus}\beta _{b} \hat{b}_{i} {\minus}\left( {\alpha _{d} {\plus}\beta _{d} \hat{d}_{i} } \right){\asterisk}(\alpha _{b} {\plus}\beta _{b} \hat{b}_{i} ) \cr & {\equals} \ \alpha {\plus}\beta \hat{d}_{i} {\plus}\gamma \hat{b}_{i} {\minus}\delta \hat{d}_{i} \hat{b}_{i} $$

$$\eqalignno{ \Pr\left( {Y_{i} \,\mid\,\widehat{{d, }} \hat{b}} \right) & {\equals} \Pr \left( {d_{i} \,\mid\,\hat{d}_{i} } \right){\plus} \left[ {1{\minus}\Pr \left( {d_{i} \,\mid\,\hat{d}_{i} } \right)} \right]{\asterisk}\Pr \left( {b_{i} \geq 0{\rm \,\mid\,}\hat{b}_{i} } \right) \cr & {\equals} \ \alpha _{d} {\plus}\beta _{d} \hat{d}_{i} {\plus}\alpha _{b} {\plus}\beta _{b} \hat{b}_{i} {\minus}\left( {\alpha _{d} {\plus}\beta _{d} \hat{d}_{i} } \right){\asterisk}(\alpha _{b} {\plus}\beta _{b} \hat{b}_{i} ) \cr & {\equals} \ \alpha {\plus}\beta \hat{d}_{i} {\plus}\gamma \hat{b}_{i} {\minus}\delta \hat{d}_{i} \hat{b}_{i} $$What is unusual about Equation (3) is the interaction term,  ${\minus}\delta \hat{d}_{i} \hat{b}_{i} $. This interaction mathematically captures an intuitive property of obligation: as a sense of national obligation strengthens, payoff considerations become less important in the willingness to comply. That is, the explanatory weight of the latter is reduced (hence the negative sign). Note that if national identification matters through a payoff mechanism instead, such as pursuit of national interest or status, this interaction term should be zero. There is no reason to expect a trade-off between different kinds of payoffs; each should only be additive to a utility function.Footnote 34 Thus, the presence (or absence) of a negative interaction serves as a test for whether an obligation to the nation is an underlying mechanism.

${\minus}\delta \hat{d}_{i} \hat{b}_{i} $. This interaction mathematically captures an intuitive property of obligation: as a sense of national obligation strengthens, payoff considerations become less important in the willingness to comply. That is, the explanatory weight of the latter is reduced (hence the negative sign). Note that if national identification matters through a payoff mechanism instead, such as pursuit of national interest or status, this interaction term should be zero. There is no reason to expect a trade-off between different kinds of payoffs; each should only be additive to a utility function.Footnote 34 Thus, the presence (or absence) of a negative interaction serves as a test for whether an obligation to the nation is an underlying mechanism.

The two hypotheses are tested in the context of voting, a quintessential role of the democratic citizen. Since the theory is about why citizens are willing to comply, the outcome of interest is not turnout, but a sense of citizen duty to vote. The specification model, based on Equation (3), is as follows:

$$\eqalignno{ duty \ to \ vote_{i} \ {\equals} \ & \beta _{0} {\plus}\beta _{1} (national \ identification )_{i} {\plus} \beta _{2} (payoffs)_{i} \cr & {\minus} \beta _{3} \left( {national \ identification \, {\times} payoffs} \right)_{i} {\plus} \beta _{4} (controls)_{i} {\plus}{\epsilon} $$

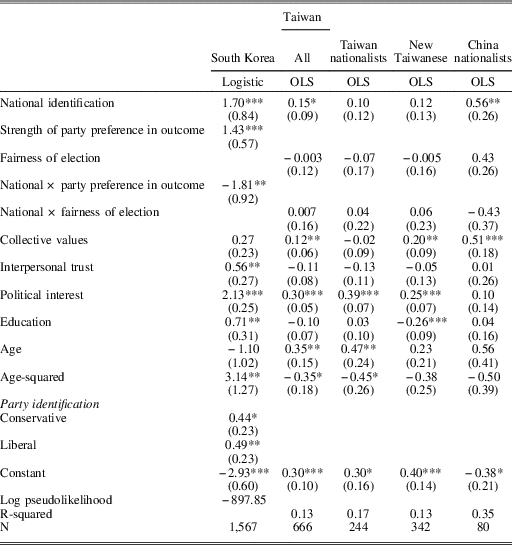

$$\eqalignno{ duty \ to \ vote_{i} \ {\equals} \ & \beta _{0} {\plus}\beta _{1} (national \ identification )_{i} {\plus} \beta _{2} (payoffs)_{i} \cr & {\minus} \beta _{3} \left( {national \ identification \, {\times} payoffs} \right)_{i} {\plus} \beta _{4} (controls)_{i} {\plus}{\epsilon} $$Table 1 shows the individual-level predictions. On average, national identification should play a significant role in explaining the duty to vote in South Korea, but not in Taiwan. Then subnationally within Taiwan, we should see a negligible effect of national identification on the duty to vote for all identity groups except China nationalists.

Table 1 Individual-Level Survey Predictions

Symbols + and − mark the predicted direction of the variable’s effect on citizen duty to vote.

Data and measurement

In South Korea, a face-to-face, nationally representative survey (N=2,047) was fielded in May 2012 by Seoul National University. In Taiwan, an online survey (N=1,004) was fielded to a nationally representative panel maintained by National Chengchi University in July 2013. The usual concerns with opt-in surveys apply here, and the data were weighted to minimize selection bias.Footnote 35

The dependent variable is a sense of citizen duty to vote. The following question was similarly replicated in both surveys. The wording, adapted from Blais and Achen,Footnote 36 spells out what type of behavior is meant by ‘duty’ and offers an equally acceptable, alternative norm of voting as a personal choice to minimize over-report:

Different people think differently about voting. Some people think that voting is a responsibility, and you should vote even if you don’t like any of the candidates or parties. Other people think that it is all right to vote or not vote, and the decision depends on how you feel about the candidates or parties. Do you think voting is a responsibility or that it is all right to either vote or not vote?

The duty to vote was coded as a binary measure in South Korea (0=no duty, 1=duty). In Taiwan, a follow-up question on strength of opinion was included, so that the variable was coded as a continuous strength of duty to vote (0=none, 1=weak, 2=strong).

The independent variable is strength of national identification, the observable source of national obligation. In South Korea, where national identity is racially understood and the citizenry is largely homogeneous, there is little confusion about membership. But asking about strength of identification with that identity, where almost everyone is Korean ‘by nature’, proved to be awkward in the native language. A focus group with college students revealed that national pride better captured a psychological attachment to the nation. Thus, I asked ‘how proud are you to be Korean?’ under the assumption that strength of identification increases monotonically with pride.

In Taiwan, the standard measure of ‘how strongly do you identify with Taiwan?’ was asked. But because the meaning of ‘Taiwan’ is contested on the island, two individuals could reply with the same level of identification and feel it towards two different national communities. Thus, a follow-up battery asked respondents to define the territory, countrymen, government and culture of what is meant by ‘my Taiwan’. The battery, adapted from Wang and Liu,Footnote 37 captures the two dimensions on which national identity is primarily contested – political versus cultural independence.Footnote 38 Based on their answers, respondents were categorized into three national types: Taiwan nationalists, who identify with Taiwan as politically and culturally independent from China; New Taiwanese, who identify with Taiwan as politically independent but culturally part of China; and China nationalists, who identify with Taiwan as politically and culturally part of China. See Appendix 1 for details. In the pooled analysis, the strength of national identification measure is used without distinguishing the national types to reflect the low degree of nation-state linkage on the island as a whole; in the subnational analysis, the effect of national identification is examined separately by national type.

I consider two payoffs related to voting. In South Korea, I look at strength of partisan preference in the election outcome. The logic is that those who care more about who wins should expect greater psychic payoffs from voting. The same variable is not available in Taiwan, since the survey was not during an election year. A general strength of partisan attachment measure is also problematic, as the two major parties are primarily defined by their position on national identity. In the subgroup analysis by nation type, this means that the variable is highly correlated with strength of national identification itself. What we need is a measure of payoff from voting that is not politicized along the lines of national identity. Thus for Taiwan, I consider fairness of elections – how fair one believes the state is in collecting and counting the votes. A large literature on contractual trust and compliance emphasizes fairness of procedure as an important source of payoff: ‘If there is a mechanism to assure that outcomes are distributed fairly, long-term membership in the group will be rewarding’.Footnote 39 Applied to voting, those who see the electoral decision-making process to be fairer should have greater trust that their vote will count equally, thus expecting greater expressive benefits from voting and long-term utility from doing one’s part to support that system.Footnote 40

Additionally, I also control for potential attitudinal confounders. Collective values – the belief that one should always sacrifice for the group – and interpersonal trust are controlled for, as they can potentially drive both stronger national identification and the duty to vote. I also include known predictors of the duty to vote:Footnote 41political interest, age, age-squared, education and, for South Korea only, party identification. Appendix 7 shows summary statistics for all key variables.

Results are shown in Table 2. In South Korea, stronger national identification is associated with a greater sense of duty to vote. Even for someone who has no preference in which party wins, strong national identification alone leads to a 5.5 times higher odds of seeing voting as a duty. Importantly, the interaction term between strength of national identification and payoffs is negative.Footnote 42Figure 1 plots the interaction. We see that as strength of national identification increases, the marginal effect that preference over the outcome has on the duty to vote steadily decreases towards zero. In other words, for someone who strongly identifies with her nation, how much she cares about which party wins essentially does not matter any more in her willingness to vote. This is precisely and uniquely what a sense of ethical obligation to the nation implies.Footnote 43

Fig. 1 Negative interaction as proxy for ethical obligation to nation The figure plots the interactions from Table 2: how the marginal effect of payoff varies with strength of national identification. Y-axis is the estimated coefficient of the payoff variable across different levels of national identification (holding all other variables at their actual values).

Table 2 National Identification and Citizen Duty to Vote in South Korea and Taiwan

***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.10. All variables rescaled to 0-1.

A different picture emerges in Taiwan. On average, stronger national identification is associated with a 15 per cent greater duty to vote,Footnote 44 but subnational analyses reveal that this effect is almost entirely sustained by the minority of China nationalists – the only group with strong nation-state linkage. This is also the only group for whom we see a negative interaction indicative of an ethical obligation to the nation. For the other two groups with weak or absent nation-state linkages, the effect of national identification is not significant and leads to no meaningful interaction, as shown by the flat lines in Figure 1.

The explanation put forth in this article is that, under a state with pro-China legacy, Taiwan nationalists and New Taiwanese feel little ethical obligation to ‘my’ nation to comply with the state. Their sense of citizen duty to comply may be sustained by other factors, but an ethical obligation to the nation is not one of them.

A series of checks against alternative explanations further supports that interpretation. First, the subnational patterns in Taiwan do not appear to be reducible to systematic differences between the national types, or how the types were categorized. The mean and distribution of the strength of national identification variable are statistically indistinguishable across the groups. One possible confounder is that civil servants, who presumably have greater levels of citizen duty to comply, tend to come disproportionately from China nationalist backgrounds. While this pattern holds nationally, it is not the case in this particular online sample, with civil servants comprising 15 to 17 per cent of all national types. The results are also robust to a different categorization of national types that reflect the growing importance of the political dimension and fading significance of cultural difference with generational turnover.Footnote 45 Appendix 8 shows that the patterns remain identical, and if anything, are more exaggerated.

Second, the results appear to reflect a general orientation towards citizen compliance with the state, not just voting. Appendix 3 shows that similar cross-national and subnational patterns extend to citizen duty towards tax compliance, for example.

Third, the results are not reducible to a partisanship effect. Especially in Taiwan, since the vast majority of China nationalists are KMT supporters and the data were collected under a KMT president, one might wonder if the results simply reflect loyalty to a party instead. However, Appendix 4 shows that the percentage of individuals presumably voting out of a sense of duty was still higher among China nationalists even during DPP incumbency, suggesting that the findings likely reflect deeper identity effects as theorized.

Perhaps the strongest way to show that an ethical obligation is real is to pit it directly against payoffs. Do individuals hold steadfastly to an obligation to the nation, even at a potential cost to themselves? To see, I asked the following question in the Taiwan survey: ‘How much do you approve or disapprove some of your tax money being spent to improve air pollution in mainland China?’ The beneficiary is designated as individuals living outside of the island, who are co-nationals only for China nationalists. If ethical ties to ‘my’ nation explain the results of Table 2, then for China nationalists only, stronger national identification should lead to greater support for this policy, even though it takes tax money away from the island.

The results in Table 3 are consistent with an ethical mechanism. For China nationalists, strong national identification is still associated with a 30 per cent higher support for a state policy that imposes a cost on themselves. It is difficult to imagine a payoff-based explanation for these patterns without making unrealistic assumptions about the imminence of unification with China or selective exposure to polluted air.

Table 3 Support for Tax Policy to Help China’s Pollution: Testing Ethical Obligation versus Payoffs in Taiwan

***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.10. All variables rescaled 0-1.

So far, survey evidence suggests that a sense of obligation to the nation is a real motivation behind the willingness to comply. But as a causal mechanism, national obligation is still implied in the patterns found in observational data. The following pair of experiments addresses this limitation by explicitly priming national obligation as the reason to comply.

Experimental Evidence

South Korea: a turnout field experiment in a mobile election

In South Korea, I inserted the national obligation prime into a mobile election held by the National Election Commission (NEC). The election was a pilot test for a new mobile voting application, where participants vote via SMS text. A total of 2,097 valid NEC employees were recruited.Footnote 46 To maintain real stakes in voting, the ballot included a mix of national issues as well as topics that affect NEC employee life. The election was held across two days – 13 and 14 August 2013 – and participants were randomly assigned to one of the days. On election day, participants received an interactive text message through which they cast their vote.

The treatment was embedded in an email sent to all participations via Qualtrics one day before their assigned election day. The control group (N=1,073) received an informational email with directions. The treatment group (N=1,024) received the same email, but with an appeal to national obligation as the reason to vote, bolded in Table 4. At the bottom of both emails was a link to an optional pre-election survey that asked, among other items, the duty to vote using the same wording as in the survey portion of the analysis.

Table 4 Experimental Treatment in South Korea

The worry with mailer experiments is whether subjects actually read and received the treatment message. In the current setup, because duty to vote is measured only among the 357 subjects who filled out the optional pre-election survey at the bottom of the email, those who did most likely read the treatment message as they scrolled down the screen. The average treatment effect should therefore closely approximate the true complier average causal effect. However, the survey’s opt-in nature introduces potential selection bias. To ensure that the only observable difference between individuals who opted into the survey in the control versus treatment conditions is exposure to the prime, I also calculate the treatment effect only among matched control-treatment pairs based on age, education, gender and years spent at the NEC.

Table 5 shows the treatment effects, unmatched and matched. Among all subjects who filled out the pre-election survey, duty to vote in the treatment group was 9 percentage points higher than in the control group (0.59 versus 0.68). This effect size nearly doubles to 13 percentage points among matched pairs only, the more precise estimate.

Table 5 Experimental Results in South Korea

***p<.01, **p<.05, *p<.10. Matching for control-treatment pairs conducted only among subjects who filled out the optional pre-election survey. Nearest neighbor method used with bootstrapped standard errors.

The effect on actual turnout, individually validated through mobile numbers, is likewise impressive. On average, turnout was 6 percentage points higher in the treatment group (0.81 versus 0.75). This effect size exceeds that found in most get-out-the-vote experiments using mailers or phone calls, falling short of only induced public shamingFootnote 47 and face-to-face canvassingFootnote 48 – strategies that are too controversial or expensive to implement broadly. Among the matched pairs only, the effect size remains similar at 5 percentage points.Footnote 49 Notably, priming individuals’ sense of obligation to their nation – the theorized source of citizen duty – appears to be much more effective than simply telling them that it is their duty to vote, which Gerber, Green and Larimer find increases turnout by only 1.8 percentage points.Footnote 50

The South Korea experiment shows that where nation-state linkage is strong, priming individuals’ sense of ethical obligation to the nation produces real gains in citizen duty to vote and actual turnout.

Taiwan: survey priming experiment

In a place like Taiwan, the same substantive treatment should yield only a negligible effect on citizen duty to comply. The experiment came at the very end of the same internet survey used in the survey portion of the analysis. Subjects were randomly assigned to one of two versions of a news article about the 921 Earthquake, a well-known national disaster that hit in 1999. The event was chosen for two reasons: first, earthquakes are a real and constant threat to the island and so state requests for citizen volunteerism are realistic; second, natural disasters are moments of exigency when the ‘moral glue’ within a group is heightened,Footnote 51 lending a ripe context for priming effects.

The control group (N=504) read the ‘neutral’ frame article that described objective facts about the disaster, while the treatment group (N=500) read the ‘national obligation’ frame article that included anecdotes exemplifying national obligation. Appendix 5 shows the wording of each article and balance checks of pre-treatment covariates. After reading the article, subjects were told that the state is considering enlisting citizen volunteers in the event of another earthquake. They were then asked whether they thought complying with state requests by volunteering or donating is a matter of duty or personal choice.

Unlike most experiments, the prediction here is a null effect, since the majority of subjects perceive nation-state linkage to be weak or absent. Figure 2 shows that, on average, the national obligation treatment did have a null effect on citizen duty to comply. But a null effect can also be due to a weak treatment. Dividing the subjects by national identity type reveals that this is unlikely. While the null effect holds for Taiwan nationalists, for China nationalists – the only group with strong nation-state linkage – the treatment increased citizen duty to comply by 18.5 per cent (p< 0.047).Footnote 52

Fig. 2 Experimental results in Taiwan X-axis represents OLS estimates of treatment effect on strength of duty to comply with state requests for volunteers and donations (rescaled 0-1). Error bars are 95 per cent confidence intervals.

The divergent result is not due to some idiosyncratic feature of the treatment that made it more effective among China nationalists.Footnote 53 A manipulation check in Appendix 6 shows that the treatment was similarly effective in boosting closeness to ‘my’ nation for both groups, but still led to contrasting effects on citizen duty to comply. The Taiwan results suggest that in places where nation-state linkages are weak or absent for most citizens, appeals for voluntary compliance based on national obligation tend to fall on deaf ears.

The empirical findings across two different methods suggest, with remarkable consistency, that national obligation is a real reason behind a citizen duty to comply and empirically distinguishable from payoffs. At the same time, the cross-case variation demonstrates that this ethical pathway is highly contextual. National obligations are politicized in support of compliance only under conditions of strong nation-state linkage. When such linkage is weak or broken, the data show with equal consistency that the ethical pull of the nation remains largely untapped towards compliance.

CONCLUSION

Why do citizens choose to comply with the state in democracies, especially when coercion is weak or absent? This article shows that ethical ties to the nation are a powerful motivation that has been missed by prior scholarship. For citizens who perceive strong linkage between their nation and state, acts of democratic compliance are seen as ‘ritualized means of fulfilling moral responsibilities’ to their national communities.Footnote 54 When present, this ethical lens reduced the importance of payoff considerations, survived in the face of potential costs, and led to one of the highest treatment effects on validated turnout found in the literature. The proportion of the citizenry that is willing to comply out of such ethical obligation to the nation will vary by state. But as the case of South Korea demonstrates, in certain contexts, it can be a considerable part of the population.

The findings suggest that citizen willingness to vote and otherwise participate in the democratic state will typically be weaker in places with nationalist contentions or divisions. One reason might be that differing preferences between national groups makes co-operation less desirable.Footnote 55 This study suggests that another powerful and potentially stickier reason is that, in such places, fewer citizens feel a direct obligation to the state for reasons of national identity. Weaker nation-state linkage attenuates an ethical obligation to comply, even for civic democratic national groups such as the New Taiwanese. What appears to matter is the context, not content, of national identity.

In democracies with nationalist contentions, inclusionary policies that aim to improve or reconstruct perceptions of nation-state linkage can be long-term investments towards building a more responsible and engaged citizenry. These might include formal policies that shape how citizens view the national identity of the state, such as representation quotas that reflect national diversity in state positions or laws around citizenship access. Change can also occur through subtler channels, such as by shifting the way that the national community of the state is visually portrayed in civic education and mainstream media channels.

The article also brings new evidence to the ongoing debate on the ambiguous role of nationalism in liberal democracies. Liberal democratic theory, with its emphasis on individualism and rationality, has always sat uneasily with the binding power of group attachments. Empirically, strong nationalism has been linked to both state-supportive outcomes, such as better public goods provision and co-operation, as well as state-disruptive outcomes, such as violence or separatist movements.Footnote 56 Such seemingly contradictory accounts have led some scholars to argue that perhaps certain kinds of nationalisms are better fit for liberal democracy than others.

Instead, this article suggests that the democratic consequence of nationalism is highly contextual. It demonstrates that under certain conditions, strong national identification – even of the ethnic kind – can work ‘for rather than against democracy’s rise and consolidation’.Footnote 57 The study is a rare and systematic effort to empirically assess the counterintuitive position long held by liberal national theorists:Footnote 58 that communal – and specifically national – attachments are an important and even necessary part of the functioning of liberal democracy.

Future work might further nuance the normative implications of the theory. The communal logic of compliance is certainly not restricted to democracies. Authoritarian states can, and repeatedly have, fanned national obligations to motivate their citizens to contribute to non-democratic ends. Like any other political resource, communal obligation can be exploited. To what limits, and to what consequence for democratic transitions and survival, are important empirical questions raised by this study.