The normative appeal of international law is predicated upon the view that well-designed rules will – in general and on average – promote peace, stability and good governance.

(Goodman and Jinks Reference Goodman and Jinks2003, p. 171)

Why do states that ratify human rights treaties violate human rights more often than those countries that do not ratify such treaties? Researchers continue to puzzle over the empirical finding that countries that ratify the various instruments within the global human rights regime are more likely to abuse human rights than non-ratifiers over time.Footnote 1 In a recent paper, I have identified a possible answer to this question: the set of expectations used by monitoring agencies to hold states responsible for repressive actions has become increasingly strict over time.Footnote 2 Changes to this ‘standard of accountability’ mask real improvements to the level of respect for human rights in data derived from human rights monitoring reports, which implicitly incorporate these increasingly stringent assessments of state behaviors. Once this changing standard of accountability is taken into account using a new latent variable model of repression, the relationship between ratification of the UN Convention Against Torture and respect for human rights becomes positive.Footnote 3 This result suggests that (1) countries which respect human rights are more likely to ratify the UN Convention Against Torture in the first place, (2) the treaty has a causal effect on human rights protection once ratified, or even possibly (3) both. This new finding has broad implications for the human rights, international relations, and international law literatures, because it suggests that the international human rights regime is not simply cover for human rights abusers but is instead associated with respect for human rights and improvements in state behaviors over time. But what about the relationship between respect for human rights and the many other international human rights conventions that are a part of the global human rights regime?

In this article, I demonstrate that there are systematic differences in the relationship between the level of respect for human rights – when the changing standard of accountability is and is not accounted for – and several widely studied international human rights treaties (measured in several different ways). Specifically, correlations that were once found to be negative are actually positive. I demonstrate that these new positive relationships hold generally for a set of human rights treaties, which are measured using a standard additive approach commonly used in the treaty compliance literature to capture the level of embeddedness of a state within the international human rights regime over time.Footnote 4 I also introduce a new measure of the global human rights regime using a dynamic latent variable model similar to the one developed by Martin and Quinn to model the ideology of Supreme Court Justices over time.Footnote 5 Overall, when changes in the standards used to assess state abuse are taken into account, the negative relationship between respect for human rights and ratification of human rights treaties is reversed across several different human rights treaty variables. The results suggest that the ‘normative appeal of international law’ may not be in doubt as earlier empirical research suggests.Footnote 6

In the remainder of this article, I first describe the disagreement that exists within the literature on international treaty compliance and how this relates to the changing standard of accountability. The acknowledgment and assessment of the standard of accountability has major implications for this debate. Next, I describe the existing measurement strategies used to assess human rights behaviors and treaty compliance and then demonstrate how the new human rights data changes existing relationships with both old and new measurements of treaty ratification over time. Finally, I conclude with suggestions for future research.

HUMAN RIGHTS TREATY COMPLIANCE AND THE CHANGING STANDARD OF ACCOUNTABILITY

In this section, I describe the disagreement between scholars on state compliance with international human rights treaties. I then describe how changes to the standard of accountability over time help to explain the anomalous empirical findings reported in earlier studies, which catalyzed this debate.

Understanding the relationship between respect for human rights and the effectiveness of UN human rights treaties is important for the human rights, international relations, and international law literatures because there are two divergent arguments about treaty effectiveness. Some authors argue that treaty ratification constrains states by creating costs for noncompliance, which modifies state behaviors.Footnote 7 Alternatively, treaty ratifications only occur in cases in which the regime would have complied with the provisions of a treaty regardless of whether or not the treaty was ever ratified. Thus, treaties have no effect on the codified behaviors within the specific treaty, such as the level of cooperation,Footnote 8 or human rights compliance.Footnote 9 According to this group of scholars, treaty ratification is simply a reflection of the preferences of the political leader. The theory and data presented in this article cast considerable doubt on this second interpretation.

As described above, there is considerable debate about the reasons for the negative correlations found between respect for human rights and treaty compliance reported in earlier research.Footnote 10 Using more sophisticated research design strategies that provide more plausible evidence of causal effects, scholars have found evidence for positive relationships between treaty ratification and human rights compliance under certain conditions.Footnote 11 For example, ratification of international treaties is associated with improvement in women’s protections and select civil and political rights under certain conditions.Footnote 12 Even more recent evidence suggests that ratification of the Convention Against Torture actually reduces torture in cases in which leaders are secure in their jobsFootnote 13 or when many legislative veto players are present and constrain political leaders based on rules written into law.Footnote 14

Unfortunately, with the exception of my recent article, all of the published empirical assessments of these opposing viewpointsFootnote 15 have made use of data measuring repression derived from the same human rights reports.Footnote 16 The data used in these studies do not account for the changing standard of accountability, which confounds the relationship between treaty compliance and respect for human rights.

As I demonstrate in this article, the acknowledgment and assessment of the standard of accountability has major implications for the treaty compliance debate because it identifies changes to human rights reporting that correspond in time with the increasing embeddedness of countries within the global human rights regime. Importantly, the empirical evidence presented in this article, based on new human rights estimates that account for the changing standard of accountability, bolsters the positive statistical associations for the effectiveness of the human rights regime on human rights behaviors reported in some of these more recently published studies.Footnote 17 This occurs because these previously reported positive effects were discovered using biased data that did not account for changes to the standard of accountability over time. That is, the substantive effects reported in these published studies are likely to be stronger than previously thought. Finally, the results reported in this article directly contradict the negative correlations reported in earlier studiesFootnote 18 and cast considerable doubt on studies that begin with this negative correlation as a puzzle needing to be explained.Footnote 19

Why do changes to the standard of acceptability confound the relationship between treaty ratification and compliance? In my previous article I have shown that the standard of accountability – ‘the set of expectations that monitoring agencies use to hold states responsible for repressive actions’ – has changed due to a combination of three mechanisms or tactics: (1) information, (2) access, and (3) classification.Footnote 20 Over time, observers and activists update these tactics in order to reveal repressive practices to the international community, understand why those practices occurred in the first place, and eventually change those practices for the better. Over the same period of time, however, state officials have signed and ratified an increasing number of UN human rights treaties, thus becoming increasingly embedded in the international human rights regime. To untangle the relationship between treaty ratification and state compliance then, it is also necessary to understand the process by which human rights reporting changes over time.

To understand how human rights reporting changes over time, first consider the amount and quality of information available to monitoring agencies with which to document the repressive behaviors of states. The standard of accountability changes because of improvements in the quality and increases in the quantity of information. These changes lead to more accurate assessments of the conditions in countries each year. Thus, the global pattern of human rights may appear stagnant or possibly even worse over time because of an increasing amount of information about how states respect or abuse human rights.Footnote 21 Over time, monitoring agencies are looking harder for abuse with more and better information at the same time that state officials are signing and ratifying an increasing number of UN human rights treaties.

Second and relatedly, consider the level of access to countries by non-govermental organizations (NGOs) like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. These organizations, and others like them, seek to gather, corroborate, and publish accurate information about allegations of human rights abuses. The ability to accomplish this goal has increased as these organizations grow and cooperate with one another. For example, Amnesty International and the US State Department gather allegations of human rights abuse from the reports of other NGOs that collect, publish, and share the information gathered from local or regional contexts.Footnote 22 Overall, the standard of accountability changes ‘as access to government documents, witnesses, victims, prisons sites, and other areas’, essential for assessing state compliance with international human rights law, increases.Footnote 23 Over time, monitoring agencies are looking in more places for abuse at the same time as state officials are signing and ratifying an increasing number of UN human rights treaties.

Third, consider how the classification of different types of abuse changes over time. That is, changes to the subjective views of what constitutes a good human rights record by the agencies and activists that monitor state behaviors are conditioned by the overall level of abuse or respect for human rights across countries in the international system. Today, what an observer at Amnesty International or the State Department considers to be a ‘good’ record of human rights is more stringent when compared to records from earlier years because the global average of respect for human rights has also improved. These changes occur as observers pressure governments to institute new reforms, even after other reforms have been implemented to reduce more egregious rights violations such as extra-judicial killings and disappearances. As I have argued elsewhere, ‘monitoring agencies are increasingly sensitive to the various kinds of ill-treatment that previously fell short of abuse but that still constitute violations of human rights’.Footnote 24 Moreover, there is even evidence from human rights case law of a rising standard of acceptable treatment, in which more state behaviors are classified as torture.Footnote 25 Again, monitoring agencies are classifying more acts as abuse at the same time as state officials are signing and ratifying an increasing number of UN human rights treaties over time.

Thus the relationship between treaty compliance and respect for human rights is confounded by the changing standard of accountability. What this all means for scholars of human rights, international relations, and international law, is that more recent versions of annual human rights reports represent a broader and more detailed view of the human rights practices than reports published in previous years.Footnote 26 As Sikkink notes, these organizations ‘have expanded their focus over time from a narrow concentration on direct government responsibility for the death, disappearance, and imprisonment of political opponents to a wider range of rights, including the right of people to be free from police brutality and the excessive use of lethal force’.Footnote 27 By allowing the standard of accountability to vary with time, ‘a new picture emerges of improving physical integrity practices over time (1949–2010) since hitting a low point in the mid-1970s’.Footnote 28 Though this new view should be welcomed by scholars and activists alike, these changes call into question empirical analyses of data coded from these reports because again, the changing standard of accountability confounds the relationship between treaty compliance and respect for human rights when it is not accounted for by existing measures of human rights practices. Fortunately, new data that corrects for the changing standard of accountability are now publicly available.Footnote 29

In the remaining sections of this article, I use new, publicly available human rights data to address this debate. To preview the results, I find that unobserved changes to the standard of accountability explain why correlations between all reports-based human rights variables and various human rights treaty variables are negative. When the new, corrected data are used in place of uncorrected data, the correlations between respect for human rights (i.e., compliance) and treaty ratification variables become positive. Like the relationship between the new human rights variable and ratification of the Convention Against Torture, these new results suggest (1) that countries which respect human rights are more likely to ratify UN human rights treaties in the first place, (2) that these treaties have a causal effect on human rights protection once ratified, or possibly even (3) both.

LATENT VARIABLES MODELS FOR UNOBSERVABLE CONSTRUCTS

In this section, I present information about latent variable models in three subsections. First, I present a general introduction to latent variables models and an overview of applications from various subfields in political science and related fields. Second, I present an applied version of the model, which is a dynamic binary latent variable mode, which measures the level of ‘embeddedness’ of a country within the global human rights regime over time.Footnote 30 In this subsection, I describe how I use this model to develop new latent treaty ratification estimates, which I contrast with two alternative additive treaty ratification scales and a variable that measures the proportion of ratified treaties. Third, I describe a similar latent variable model and the publicly available latent human rights estimates that I have developed, which extends the dynamic ordinal latent variable model introduced by Schnakenberg and Fariss.Footnote 31 Additional information about these models and the variables used to estimate them are available in the supplementary appendix.

An Introduction to Latent Variable Models in Political Science

Examples of latent variable or Item Repose Theory (IRT) models are now quite ubiquitous in the social sciences and political science, especially in the study of legislative ideology in the United States.Footnote 32 Scholars have also used these models in the study of international relationsFootnote 33 and comparative politics generallyFootnote 34 and in the study of human rights in particular.Footnote 35 Dynamic versions of these models are also increasingly common. The DW-NOMINATE procedure is a dynamic version of W-NOMINATE, which estimates the ideal points of members of a legislature as a function of ideal points from the previous time period.Footnote 36 Martin and Quinn introduced a Bayesian dynamic IRT model to estimate ideal points in the United States Supreme Court based on binary decision data and model the temporal dependence in these data by specifying a prior for each value of the latent variable centered at the estimated latent variable from the same unit in the previous time period.Footnote 37 Schnakenberg and Fariss build on this insight in order to extend the ordinal IRT model introduced by Treier and Jackman.Footnote 38 More recently, Fariss extends this model even further by allowing some of the item-difficulty parameters (the threshold parameters on the ordered human rights variables) to vary over time instead of being held constant.Footnote 39 That is, the baseline probability of a human rights variable being coded at a specific value is allowed to change over time.Footnote 40

The setup for the basic version of these models is quite intuitive. For the most part, the data of interest to scholars in international relations and comparative politics are made up of country–year observations indexed by

![]() $\dot{\iota }$

and t :

$\dot{\iota }$

and t :

![]() $$\dot{\iota }\,{=}\,1,...,N$$

indexes countries and

$$\dot{\iota }\,{=}\,1,...,N$$

indexes countries and

![]() $$t\,{=}\,1,...,T$$

indexes year. Of course, other grouping structures for different units are possible (e.g., students in schools, or survey respondent across counties, states, or even countries). The latent variable θ (theta) is inferred from the modeled relationship between it and the observed manifest data or items. The term ‘item’ was first used by researchers developing educational tests and refers to the correct and incorrect responses to test questions on intelligence assessments.Footnote

41

The observed items can take on any numeric value or even be missing. Data can be ratio (continuous with a true 0), interval (continuous without a true 0), categorical (ordered categories), nominal (unordered categories), or a mix of these types. For example, the data can contain continuous indicators,Footnote

42

event counts,Footnote

43

values from categorized documents,Footnote

44

nominal question responses of unknown order,Footnote

45

or again, some mix of different data types.Footnote

46

$$t\,{=}\,1,...,T$$

indexes year. Of course, other grouping structures for different units are possible (e.g., students in schools, or survey respondent across counties, states, or even countries). The latent variable θ (theta) is inferred from the modeled relationship between it and the observed manifest data or items. The term ‘item’ was first used by researchers developing educational tests and refers to the correct and incorrect responses to test questions on intelligence assessments.Footnote

41

The observed items can take on any numeric value or even be missing. Data can be ratio (continuous with a true 0), interval (continuous without a true 0), categorical (ordered categories), nominal (unordered categories), or a mix of these types. For example, the data can contain continuous indicators,Footnote

42

event counts,Footnote

43

values from categorized documents,Footnote

44

nominal question responses of unknown order,Footnote

45

or again, some mix of different data types.Footnote

46

A simple way to begin constructing a latent variable model begins with a linear regression equation (without reference to the country–year subscripts

![]() $\dot{\iota }$

to t or any other grouping referent):

$\dot{\iota }$

to t or any other grouping referent):

This model is similar to a factor analytic model but the label for the model is not an important point.Footnote

47

α represents the intercept of the model, β is the slope, and

![]() ${\rm {\varepsilon}}$

is the error term. Below, I drop ε and change the equals sign (=) to a tilde sign (~), which simply denotes a stochastic relationship between the dependent variable y and the independent variable x,

${\rm {\varepsilon}}$

is the error term. Below, I drop ε and change the equals sign (=) to a tilde sign (~), which simply denotes a stochastic relationship between the dependent variable y and the independent variable x,

Equations 1 and 2 are equivalent, though I have not specified the structure of the error process for either equation. The structure of the error is not important at this point. When x is observed, both of these equations are simple linear models and are easy to estimate. The model becomes noticeably more complicated when x must also estimated. Below, I change x to the Greek symbol theta (θ) to denote that it is also a parameter to be estimated:

In Equation 3, x is replaced by θ, which is the estimated ‘true’ or latent variable to be estimated. The theoretical interpretation of the model is that y is caused by the ‘true’ level of the latent variable θ. Stated differently; y is an observable outcome, which arises from the theoretical concept of interest. Importantly, the observation of y does not need to be perfect, especially when the researcher has an understanding of the biases related to the data generating process for a given observed item y. The more information obtained about the political process by which the observation of y occurs, the more closely it can be related to the model of the latent variable or theoretical concept of interest.Footnote 48

Again, α is the intercept or for categorical data, the baseline probability of observing a given category of y. In many latent variable applications, α represents the ‘difficulty’ in being coded at a certain level of the latent variable. β is the slope or the strength of the relationship between the ‘true’ level of the latent variable θ and the value of the observed variable y. In many latent variable applications, β represents the ability of a test or model to ‘discriminate’ between different values along the latent variable or trait (e.g., intelligence, ideology, treaty embeddedness, repression). This is a common specification for the relationship between the observed manifest variables and the latent variables.

Importantly, I wish to reiterate that there is no way to estimate a latent variable based on a single indicator.Footnote 49 If only one test score exists, then the only value to estimate the latent variable θ is the single test score itself. In this case α and β are irrelevant parameters that equal 0 and 1 respectively. However, it is possible to begin to approximate an estimate of θ with more observed information about the concept of interest. Each of the j=1,…,J indicators are for the various observed indicators that are observable manifestations of the theoretical concept of interest (e.g., intelligence, ideology, treaty embeddedness, respect for human rights). As the number of j items y j increases, the precision of the estimates of θ also increases. As Jackman points out, a researcher with only one indicator of a latent construct is unable to determine how much variation in the indicator is due to measurement error as opposed to other forms of variation in the latent construct.Footnote 50 Adding more observed information into the latent variable model allows for a more precise estimate of θ, and can be formalized for continuous variables with the following structural equation:

$$\eqalignno{ & Y_{1} \sim\alpha _{1} {\plus}\beta _{1} \theta \cr & Y_{2} \sim\alpha _{2} {\plus}\beta _{2} \theta \cr & \,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,. \cr & \,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,. \cr & \,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,. \cr & Y_{j} \sim\alpha _{j} {\plus}\beta _{j} \theta . $$

$$\eqalignno{ & Y_{1} \sim\alpha _{1} {\plus}\beta _{1} \theta \cr & Y_{2} \sim\alpha _{2} {\plus}\beta _{2} \theta \cr & \,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,. \cr & \,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,. \cr & \,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,.\,\,\,\,\,\,\,\,. \cr & Y_{j} \sim\alpha _{j} {\plus}\beta _{j} \theta . $$

Note that θ is the same for every equation, though the model parameters (here α and β) change for each equation, or more generally the function f (.). This identification strategy allows for the estimation of the latent variable and, in more complex versions of the model, the level of uncertainty about the parameter estimate. The level of uncertainty is formalized by the relative agreement or disagreement between scores across multiple indicators. The more disagreement across observed variables, the greater the uncertainty in the resulting latent variable estimates for the individual subject.

What is left for the researchers interested in estimating an unobservable concept, is the choice in what observed variables (manifest variables or items) to include in the latent variable model, the level of organization of the grouping information or subscripts (i.e., how one unit relates to another), and the function that relates the observed variable to the latent variable (α and β are part of the linear function assumed above).Footnote 51 These are each choices that should be driven by a theory of the concept of interest and then assessed using the tools of construct validity, which allow for both the assessment of the latent variable as it relates back to the theoretical concept (translation validity or how closely the estimate of θ relates to the theoretical concept) and as it relates to alternative representations of the latent variable (criterion-related validity or how the estimate of θ relates to other variables that measure the same concept).Footnote 52

This modeling approach provides a foundation for using the often flawed and incomplete data with which scholars of repression, human rights, and contentious politics must work in order to generate new insights about these important concepts. This perspective is useful because it shifts the burden of validity from the primary source documentation and raw data to the model parameters that bind these diverse pieces of information together.

Measuring the Treaty Ratification and Embeddedness of States within the International Human Rights Regime

Here, I use a dynamic binary item-response theory (IRT) model, similar to the model introduced by Martin and Quinn and quite similar to the general latent variable model described above. The model provides estimates for the level of ‘embeddedness’ of a country within the global human rights regime over time. Below, I compare this new latent variable estimate of ‘embeddedness’ with two alternative additive scales and a proportion variable each of which measure the same concept. The additive scales are simply sums of the number of treaties a country has ratified in a given year. The proportion variable is the ratio of the total number of ratified treaties for a given country out of the total number of treaties available for ratification in each year.

The dynamic binary IRT model is quite intuitive. As described in the model above, the data are made up of country–year observations indexed by i and t; i=1, …, N indexes countries and t=1, …, T indexes year. Each of the j=1, …, J indicators are for the various global treaties and optional protocols that cover a variety of human rights issues. Table 1 contains a listing of commonly studied human rights treaties that can be ratified by any country in the international system. The data can take on a value of ‘NA’, ‘0’, or ‘1’. A country–year observation is coded 1 for the year of ratification of a specific treaty and also 1 in every following year. The NAs are important because each of the treaties opens for ratification at different points in time. Thus, treaties with more ‘missingness’ will be less informative than those with less missingness over time. The uncertainty for each latent treaty variable for a given country–year is based on the number of treaties that could potentially have been ratified in a given year. As Table 1 shows, fewer treaties exist in earlier decades. The latent variable therefore represents both the level of ‘embeddedness’ of a country within the global human rights regime and the propensity to ratify new treaties as they open for ratification over time. The uncertainty for each latent treaty variable for a given country–year is based on the number of treaties that could potentially have been ratified in a given year. The error terms ε itj are independently drawn from a logistic distribution, where F (·) denotes the logistic cumulative distribution function. Each of the j treaty variables are binary y itj so the probability distribution is:

Assuming local independence of responses across units, the likelihood function for β, α, and θ given the data is:

Equation 4 refers to the probability of observing

![]() $$y_{{it}{j}} \,{=}\,1$$

, and one minus this equation refers to the probability of observing

$$y_{{it}{j}} \,{=}\,1$$

, and one minus this equation refers to the probability of observing

![]() $$y_{{it}{j}} \,{=}\,0$$

. The likelihood Equation 5 refers to the probability of the observed value in the data y

itj

. I estimate the model using independent standard normal priors on the latent treaty variable θ

it

In other words:

$$y_{{it}{j}} \,{=}\,0$$

. The likelihood Equation 5 refers to the probability of the observed value in the data y

itj

. I estimate the model using independent standard normal priors on the latent treaty variable θ

it

In other words:

for all i when t=1. The standard normal prior when t>1 is centered around the latent variable estimate from the previous year such that:

This method for incorporating dynamics was implemented in the context of a dichotomous IRT by Martin and Quinn.Footnote 53 One difference between this model and the Martin and Quinn model is that σ is estimated instead of specifying it a priori.Footnote 54

The prior for variance σ is modeled as U (0, 1). This reflects prior knowledge that the between-country variation in will be much higher on average than the average within-country variance.Footnote 55 Slightly informative gamma priors Gamma (4, 3) were specified for the β parameters. The α parameters are given N (0, 4) priors again for all of the j treaties.Footnote 56

The prior distributions for each of the model parameters help to provide a theoretical rationale for linking the latent variable θ it to the observed treaty variables y j . The normal distribution for the latent variable θ it arranges the country–year latent variable estimates under a normal density curve with mean 0 and standard deviation of 1. The mean from year to year need not be 0 and will depend on the constellation of data points for each item but the global mean for all the country–years in the model should be approximately 0. These priors are not highly informative but they do impose an overall density on the distribution of the country–year latent variable estimates. The choice in density functions, in this case a normal distribution, is up to the researcher and can be changed based on theory or new empirical information. Again though, it is important then to evaluate the output of the model using the tools of construct validity.Footnote 57 Schnakenberg and Fariss provide several different examples of empirical comparisons that are useful for assessing the validity of the estimate from different latent variable models.Footnote 58

The model assumes that any two item responses are independent conditional on the latent variable. This means that two item-responses are only related because of the fact that they are each an observable outcome of the same latent trait. In this case, the latent trait is the level of embeddedness of a country in the global human rights regime. There are three relevant local independence assumptions: (1) local independence of different indicators within the same country–year, (2) local independence of indicators across countries within years, and (3) local independence of indicators across years within countries. The third assumption is relaxed by incorporating temporal information into prior beliefs about the latent treaty variable.

Ratification is not a uniform process. Thus, a useful feature of the model is that it can also account for reservations, understandings, and declarations accompanying ratification of a treaty. States can tailor their ratification of treaties, and these adjustments have legal implications. For example, states may attach reservations that cancel application of particular provisions, or they may adopt optional provisions that increase their obligations under a treaty. These adjustments are typically referred to as reservations, understandings, or declarations.Footnote 59

I consider two important reservations that a state might make about the Convention of Torture in this article. Accounting for these different types of provisions presents a difficult modeling problem. As is mentioned in Dancy and Sikkink:

It should be noted here that ratification is not a uniform process, and it may vary from state to state. For example, states may issue declarations of reservation upon ratification, which may express an unwillingness to accept in full the provisions of the treaty. However, we do not distinguish between types of ratification for two reasons: first, it is not commonly done in the quantitative literature, on which we are building; and second, it is quite difficult to generate a coding scheme that accounts for reservations. The reason is that any reduction in the score assigned to a reserving country would be arbitrary, given that reservations are not always similar. Future research should work to generate new ways of dealing with this issue.Footnote 60

The dynamic binary IRT model can systematically account for such differences using a simply binary coding scheme for the observed variables or items. For this model, I have elected to include two binary variables, each coded 1 if a reservation, understanding, or declaration does not exist for Article 21 and Article 22, conditional on ratification of the Convention Against Torture. If this convention is ratified but with a reservation, understanding, or declaration to an article, then the binary indicators are coded 0. Otherwise the variable is coded as NA. Note again that the NA coding has substantive meaning in the context of the IRT model. Each country that ratifies the Torture Convention can choose whether the Committee against Torture may hear complaints brought against it by another state, under the optional mechanism in Article 21, or by an individual, under the optional mechanism in Article 22. It is not uncommon for states to ratify the Convention Against Torture with a reservation or declaration about these two Articles. Specifically, a country declares itself willing to recognize the Committee’s competence to hear inter-state complaints under Article 21 or individual complaints under Article 22. Overall, the model provides a principled way to incorporate this information along with the other data about treaty ratification generally.

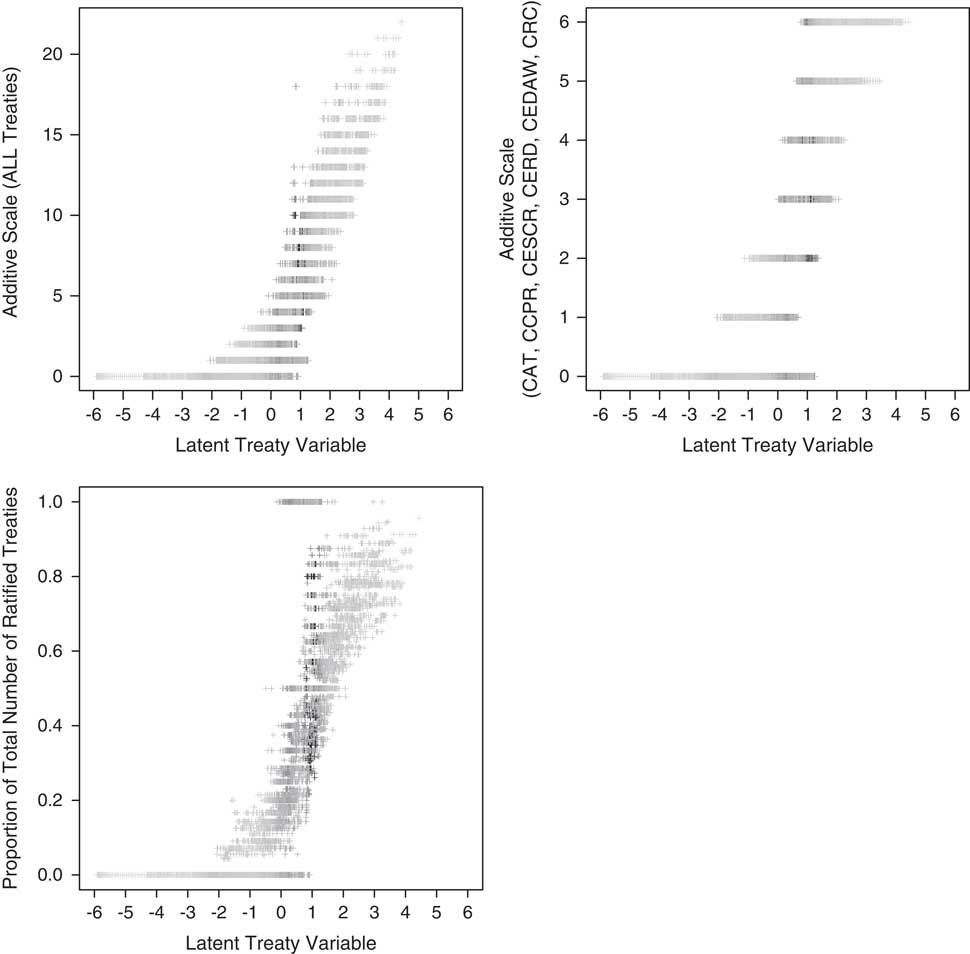

I should reiterate that there is no model-free way to estimate a latent variable.Footnote 61 An additive scale approach, typical for modeling treaty ratification behaviors,Footnote 62 is a model assuming equally weighted indicators and no error. The new latent treaty variable provides an alternative to such a model by estimating the item-weights and the uncertainty of the estimates. I compare this new latent variable, which is based on all of the treaty variables contained in Table 1 to two alternative additive scales and a proportion variable. All of these variables are closely related, though each make different assumptions.Footnote 63 However, as Figure 1 illustrates, there is considerable overlap along the latent variable for cases that are assumed to be different along the additive scales. The upper left panel compares the latent variable to an additive scale that ranges from 0 to 23 and is based on the total number of ratified treaties, optional protocols, and articles contained in Table 1. The upper right panel uses an alternative additive scale that ranges from 0 to 6 and is based on the total number of up to six ratified treaties. The selected treaties are commonly studied in the human rights literature and include the Convention Against Torture (CAT), the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The lower left panel compares the latent variable with the proportion of ratified treaties of those that are available to ratify in a given year. To generate the additive scales and the proportion variable, I recode missing values as 0 before summing across the indicators, which is the common approach when using the additive scale in the treaty compliance literature.Footnote 64 Note that this is not a necessary choice in the context of a latent variable model because this model can account for missing data. Again, the missing data have substantive meaning, which unfortunately is ignored by scholars using only an additive scale.

Fig. 1 Relationship between the latent treaty variable, two additive scales, and proportion Notes: The upper left panel uses an additive scale that ranges from 0 to 23 and is based on the total number of ratified treaties and optional protocols contained in Table 1. The upper right panel uses an alternative additive scale that ranges from 0 to 6 and is based on a total of up to six ratified treaties. The selected treaties are commonly studied in the international relations literature and include the Convention Against Torture (CAT), the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), the Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW), and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC). The correlation coefficients between the new latent variable and the additive scales are 0.795 [95% CI:0.792,0.799] and 0.754 [95% CI:0.750,0.757] respectively. The lower left panel shows the relationship between the latent variable and proportion of ratified treaties for those available each year. The correlation coefficients between these variables is 0.742 [95% CI:0.738,0.746]. We generated 95% credible intervals by taking 1,000 draws from the posterior distribution of latent treaty variables, which were then used to estimate the distribution of correlation coefficients.

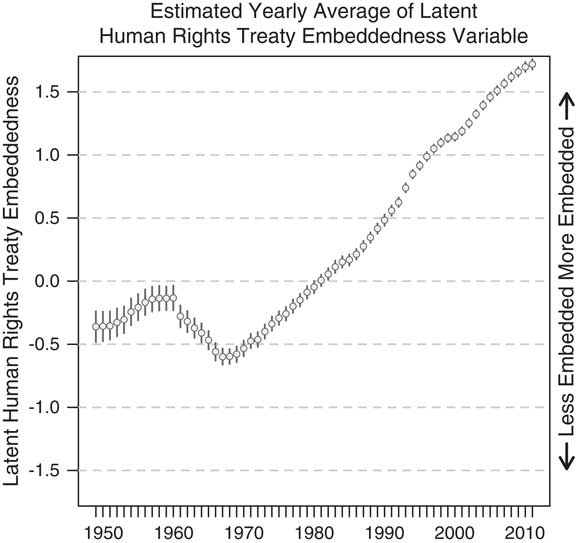

Not surprisingly, embeddedness within the international human rights regime has increased since the end of the Second World War. Section A of the supplementary appendix displays numerically and visually the model parameters that link the latent treaty variable θ to the observed binary treaty variables. Figure 2 displays the average level of embeddedness over time (see Section B in the supplementary appendix for more figures). In the next section I compare these treaty variables and the six binary treaty variables mentioned above with the two latent human rights variables.Footnote 65

Fig. 2 Average level of the human rights treaty variable over time Notes: On average, countries become increasingly embedded in the global human rights regime over time.

Measuring the Level of Respect for Human Rights

Here, I briefly describe the two sets of latent human rights estimates, which were generated with models similar to the latent treaty variable defined above.Footnote 66 These models are dynamic in the estimate of the latent variable, just like the latent treaty model presented above, but include ordered logit functions that link the ordered categorical data derived from human rights reports with the latent human rights estimates.Footnote 67 In the next section, I compare these two latent human rights variables with ten treaty ratification variables.

To reiterate, latent variable models, with their focus on the theoretical relationship between data and model parameters, offer a principled way to bring together different pieces of information, even if that information is biased. The information in the The Country Reports on Human Rights Practices published annually by the US State Department and The State of the World’s Human Rights report published annually by Amnesty International is reflective of both the historical context in which these reports were written and the true level of abuse in a given country during that period. The latent variable model I developed in 2014 provides a principled and transparent (though computationally complex) model that can account for these changes over time, which removes the temporal bias from the resulting latent variable estimates.Footnote 68

The manifestation of the changing standard of accountability has been recognized by a substantial body of human rights scholars who have developed in-depth knowledge of specific cases.Footnote 69 As Sikkink notes, monitoring agencies and others ‘have expanded their focus over time from a narrow concentration on direct government responsibility or the death, disappearance, and imprisonment of political opponents to a wider range of rights, including the right of people to be free from police brutality and the excessive use of lethal force’.Footnote 70 As I have argued, monitoring agencies are looking harder for abuse, they are looking in more places, and they are classifying more acts as abuse.Footnote 71 This argument is corroborated by several authors who suggest that the focus on police brutality, and the specific departments and locations of the abuse, in places like Brazil and Argentina are a relatively new aspect of human rights monitoring.Footnote 72 Marchesi and Sikkink specifically discuss the pattern of observation and the increasing monitoring that occurred in Brazil as it transitioned from a military regime into a democracy during the 1970s and 1980s:

This focus on police killings and torture has come to constitute the main focus of reports on Brazil throughout the 1990s and 2000s. The question is not whether this is a very serious violation of human rights. The question from the point of view of a researcher sensitive to information effects is ‘Do the Brazilian police kill and mistreat more victims today than they did in the 1970s and 1980s or do we know more about that killing and mistreatment today than we did before?’ We think it is quite possible that in the 1970s and 1980s, when the Brazilian government had large numbers of political prisoners and was killing and disappearing political opponents, the Brazilian police were also very violent with regard to criminal suspects, but such violence was not documented or reported.Footnote 73

Overall, there is a substantial amount of qualitative evidence that suggests that the standard of accountability has changed over time. The latent variable model I have developed formalizes this concept and generates new unbiased estimates of the level of respect for human rights by taking it into account.Footnote 74 The latent variable model incorporates information from thirteen original data sources. The thirteen variable names, temporal coverage, and data type of each variable are displayed in Section C of the supplementary appendix.Footnote 75

It is important to note that the version of the latent variable that does not account for the changing standard of accountability (constant standard model) is consistent with the assumptions used by all existing human rights scales.Footnote 76 For the latent human rights variable that does incorporate the changing standard of accountability (dynamic standard model), the event-based variables act as a consistent baseline with which to compare the levels of the standards-based variables. The event-based variables act as this baseline because they are each updated as new information about the specific events becomes available and are based on evidence from several regularly supplemented primary source documents (see Section C in the supplementary appendix for a list of sources); whereas, the human rights reports are produced in a specific historical context and never updated. Moreover, the producers of these events-based variables are focused on the extreme end of the repression spectrum (e.g., genocide, politicide, mass-repression, one-sided government killings). This focus makes identifying these events a relatively easier task than the more difficult one of observing behaviors such as torture.

In areas in which large scale repressive events occur, lower level abuses are often missed or simply ignored.Footnote 77 As Brysk notes, ‘Incidents of kidnapping and torture which would register as human violations elsewhere did not count in Argentina. The volume of worse rights abuses set a perverse benchmark and absorbed monitoring capabilities’.Footnote 78 These features suggest that the event-based data are a valid representation of the historical record to date, which again, acts as a consistent baseline by which to compare how the changing standard of accountability is associated with the standard-based variables over time. The changing standard of accountability is incorporated into the latent variable model of human rights by allowing the baseline probability of a human rights variable to be coded at a specific value to change over time.Footnote 79

The supplementary appendix (Section D) includes a graph that shows the difference in the two latent human rights variables each year, which illustrates the new picture that emerges of improving physical integrity practices over time. The supplementary appendix (Section E) also includes a ten-country time series graph comparing the two latent human rights estimates.

RESULTS: THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN HUMAN RIGHTS AND TREATY RATIFICATION

In this section, I illustrate the substantive importance of the changing standard of accountability for understanding human rights compliance over time by showing that ratification of UN human rights treaties and respect for physical integrity rights is positive. The results contradict negative findings from existing research. As the standard of accountability increases over time, empirical associations with human rights data derived from standards-based documents and other variables will become increasingly biased if changes in the human rights documents are not considered. This is especially true for variables that measure the existence of institutions that are correlated with time such as whether or not a particular treaty like the UN Convention Against Torture has been ratified or not.

To simplify the presentation of results, I visually compare two linear model coefficients using the dependent variable from the latent variable model that does not account for the changing standard of accountability (labeled the constant standard model) and the dependent variable from the latent variable model that does account for the changing standard of accountability (labeled the dynamic standard model). I estimate two linear regression equations using the latent physical integrity variables from the two measurement models. I run a regression of these variables on several treaty variables, including the latent treaty variable defined above, two versions of an additive treaty scale, and six binary variables. Each binary treaty variable measures whether or not a country has ratified the Convention Against Torture (CAT), the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDW), the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (CCPR), Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), or Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD) in a given year. I also include several control variables in eight different specifications.Footnote 80 Each model always includes the lagged version of one of the two human rights variables and the lagged version of one of the treaty variables.

The model comparisons demonstrate that the differences between the coefficients are similar across all of the model specifications; adding or removing any specific control variable does not change the difference between the coefficients. Thus, the results always contradict the negative findings from existing research.Footnote 81 That is, omitted variable bias does not change the substantive meaning of the difference in the relationship between treaty ratification and respect for human rights. The eight linear regression models are specified as follows:

Model 1 y it ~β 0+β 1*y i,t-1+β 2* treaty t-1

Model 2 y it ~β 0+β 1*y i,t-1+β 2* treaty t-1+β 3* Polity2 t-1

Model 3 y it ~β 0+β 1*y i,t-1+β 2* treaty t-1+β 3* Polity2 t-1+β 4*ln(gdppc t-1)

Model 4 y it ~β 0+β 1*y i,t-1+β 2* treaty t-1+β 3* Polity2 t-1+β 4*ln(gdppc t-1)+β 5*ln(population t-1)

Model 5 y it ~β 0+β 1*y i,t-1+β 2* treaty t-1+β 4*ln(gdppc t-1)+β 5*ln(population t-1)

Model 6 y it ~β 0+β 1*y i,t-1+β 2* treaty t-1+β 4*ln(gdppc t-1)

Model 7 y it ~β 0+β 1*y i,t-1+β 2* treaty t-1+β 5*ln(population t-1)

Model 8 y it ~β 0+β 1*y i,t-1+β 2* treaty t-1+β 3* Polity2 t-1+β 5*ln(population t-1)

y it is the country–year human rights variable generated from either the dynamic standard model or the constant standard model described above. Each regression model is estimated 2 by 3 by 8 times in order to compare the two competing dependent variables, using each of the three different treaty variables (the latent treaty variable and the two scales) within eight different model specifications. I also consider six additional binary treaty variables. All models include the same set of country–year observations from 1965, the year the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination opened for signature, through 2010. The results are also consistent for the period 1949 through 2010 and 1976 through 2010.

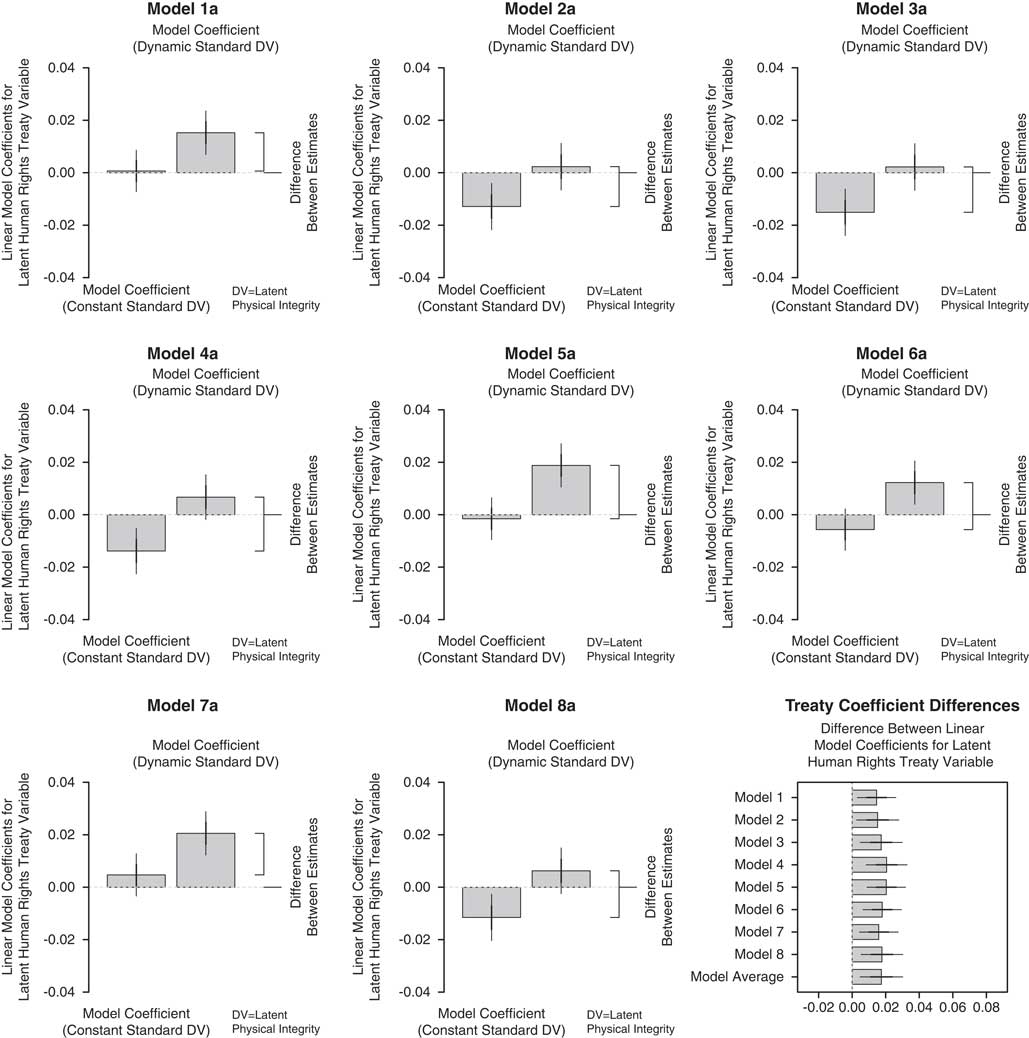

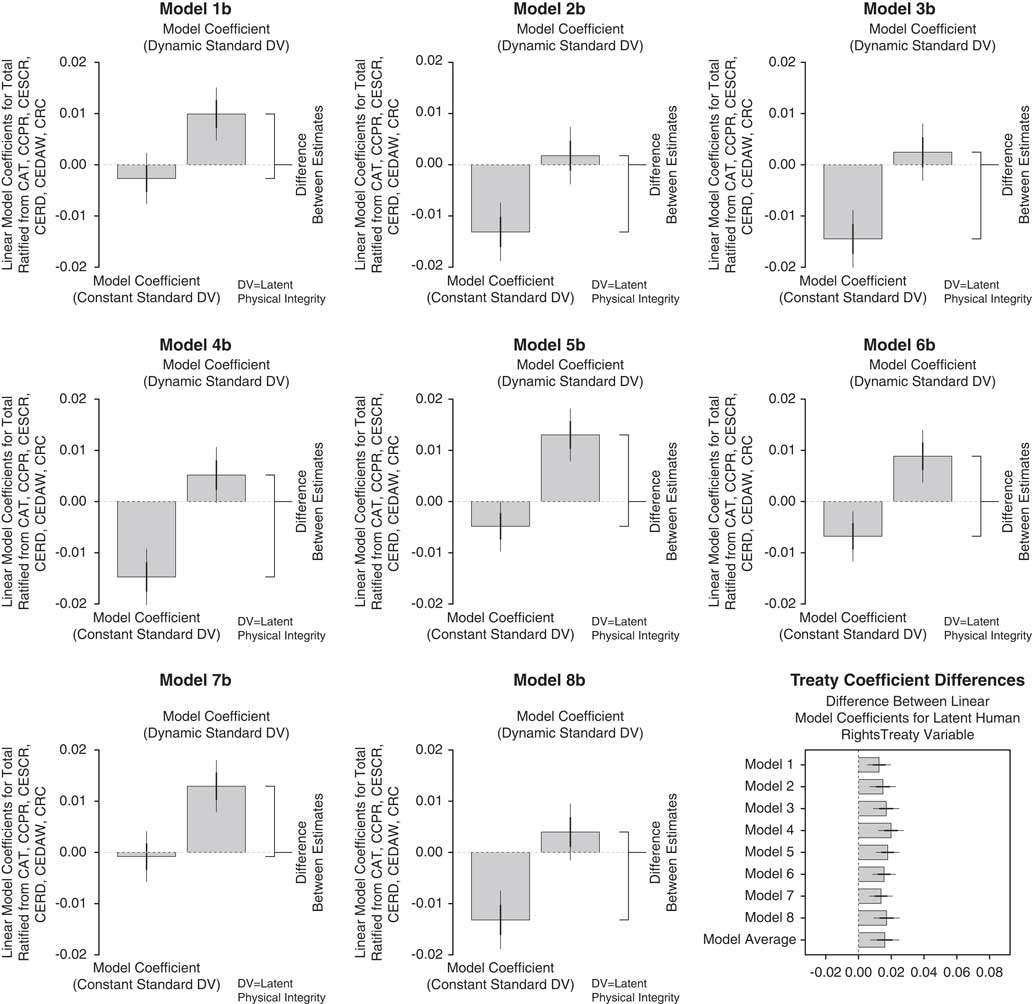

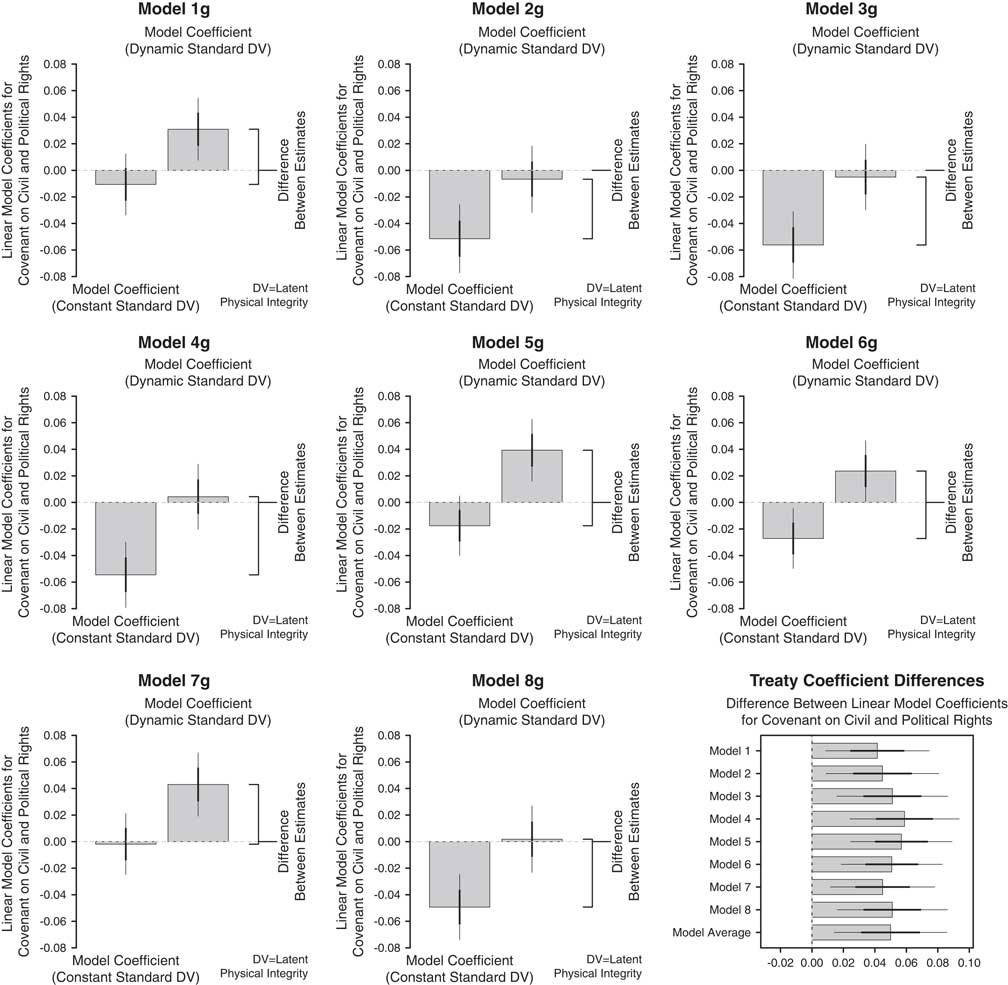

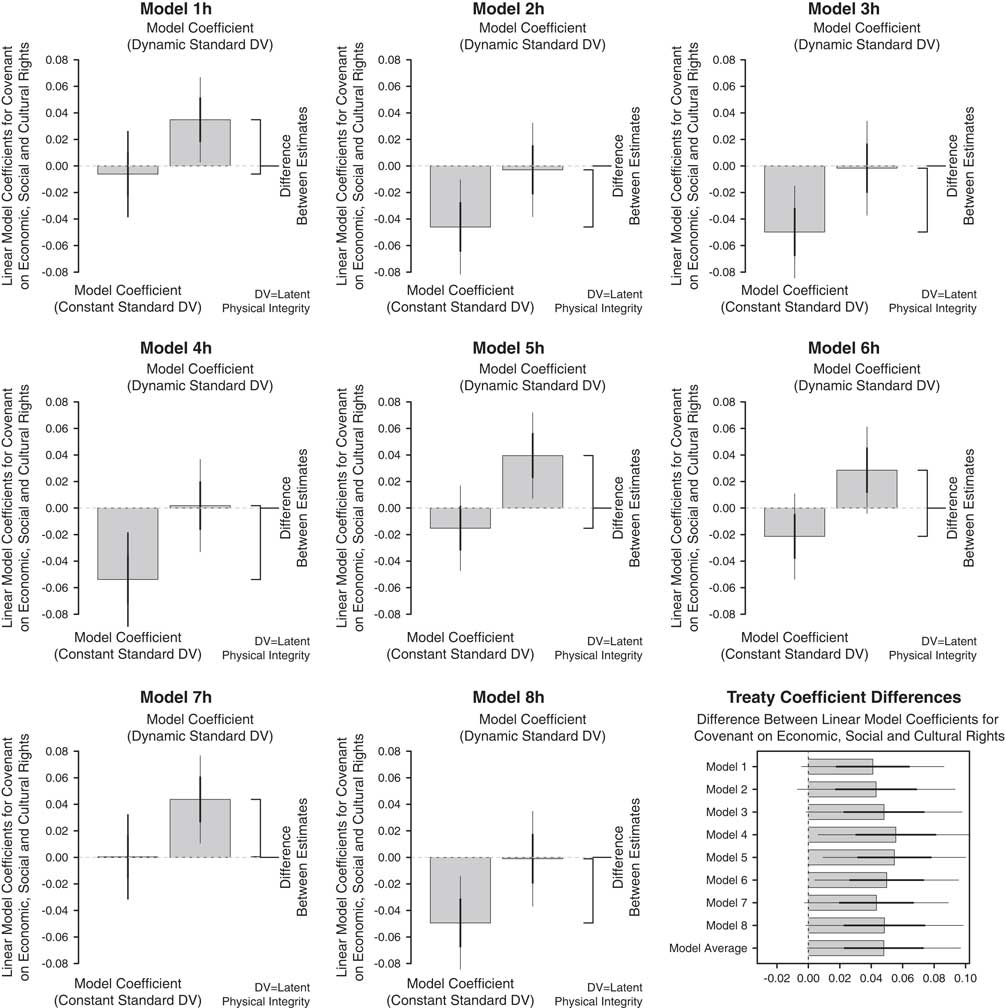

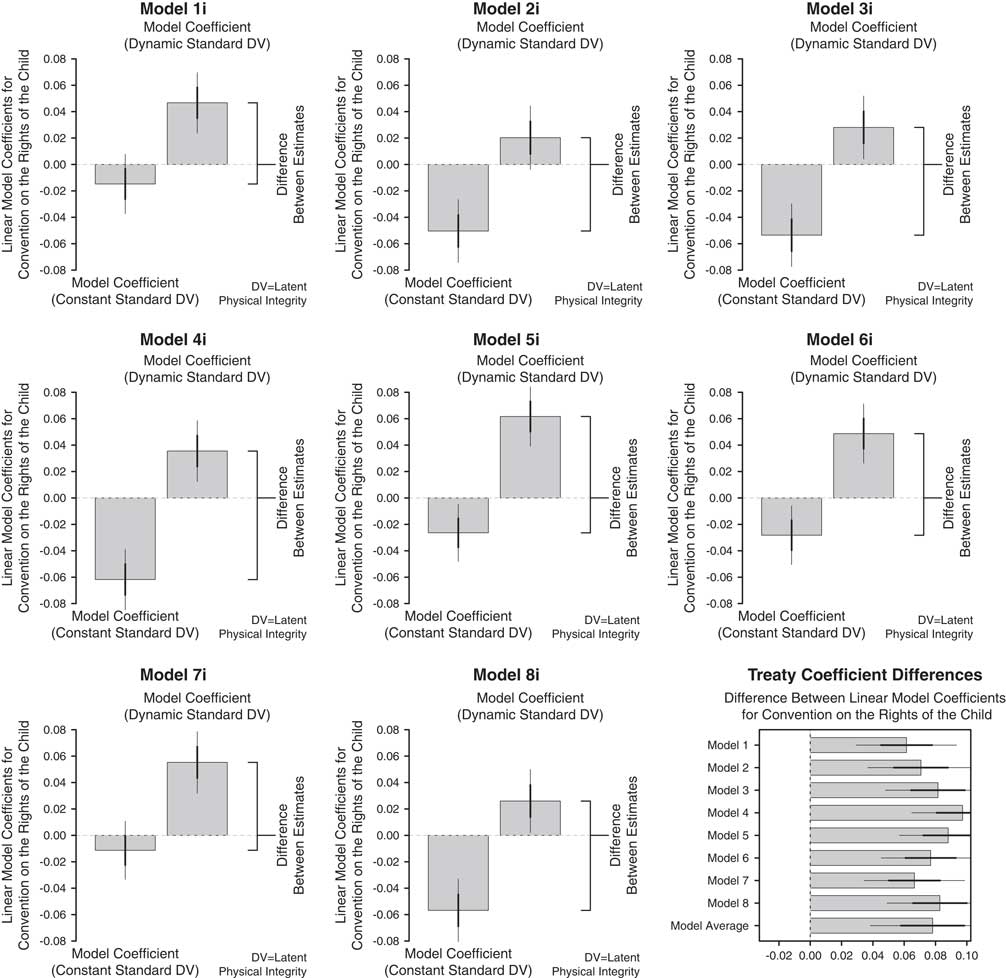

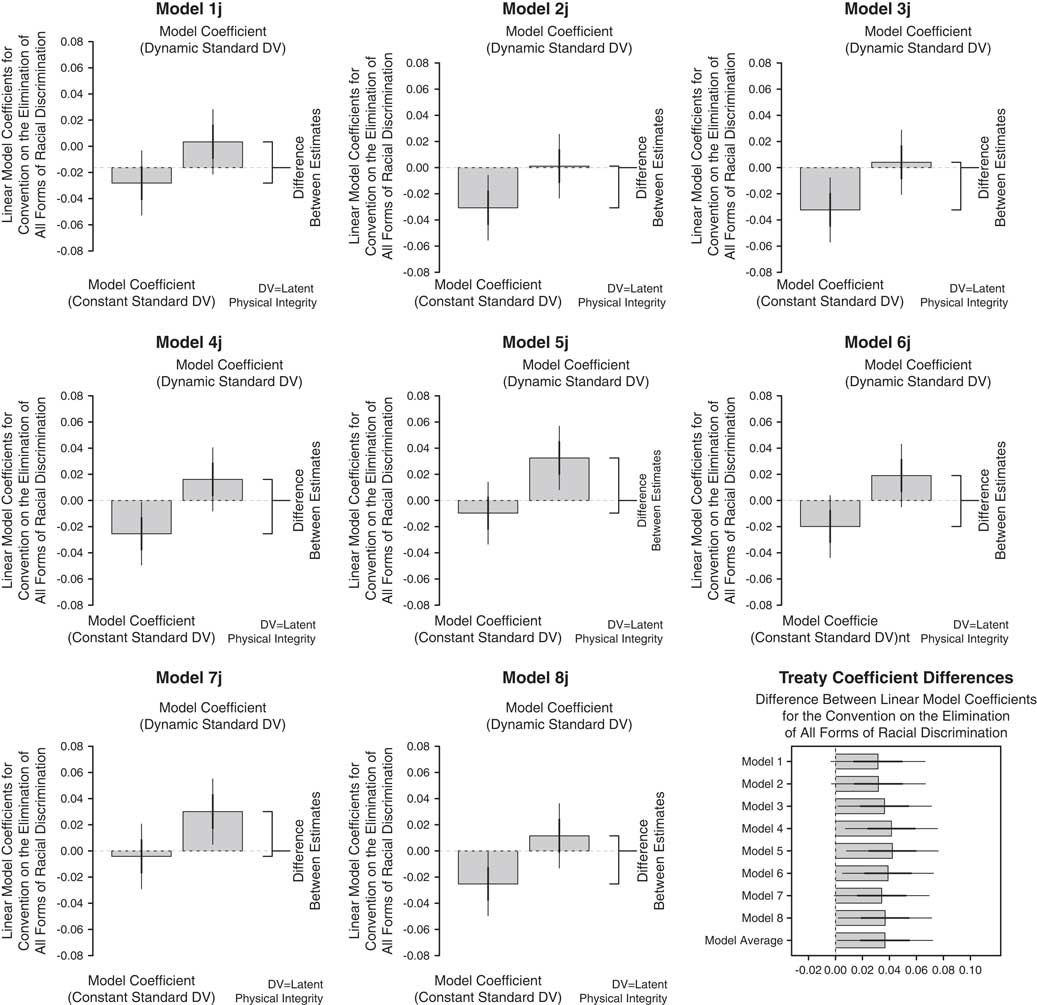

The key piece of information to consider from the various models is the difference between the coefficients estimated for the treaty variable for the two competing dependent variables. Each of the figures below visually display the two coefficients estimates for all eight model specifications using one of the treaty variables. The ninth panel in each figure displays the difference between these coefficients across the eight model specifications. This panel in each set of figures demonstrates that the differences between regression coefficients are statistically the same no matter what additional variables enter the model specification.

Though the individual coefficients for the treaty variables change across the eight models, the differences between the coefficients are consistent across all eight specifications for all treaty variables. By estimating all of the various model specifications for both dependent variables, I am able to demonstrate that the estimated difference between the coefficients using the corrected human rights variable (dynamic standard model) compared to the uncorrected human rights variable (constant standard model) are consistent and statistically different from 0. Thus, even though the individual coefficients change depending on the model specification, the differences are consistent, which is a substantively important finding that eliminates concern that the use of a particular control variable is driving the results. The differences between coefficients are therefore robust to variable selection. The coefficient for the various treaty variables flip signs in every model permutation presented across the figures and therefore contradict the negative findings from existing research. These results again suggest that human rights treaties are not simply cover for human rights abusers.

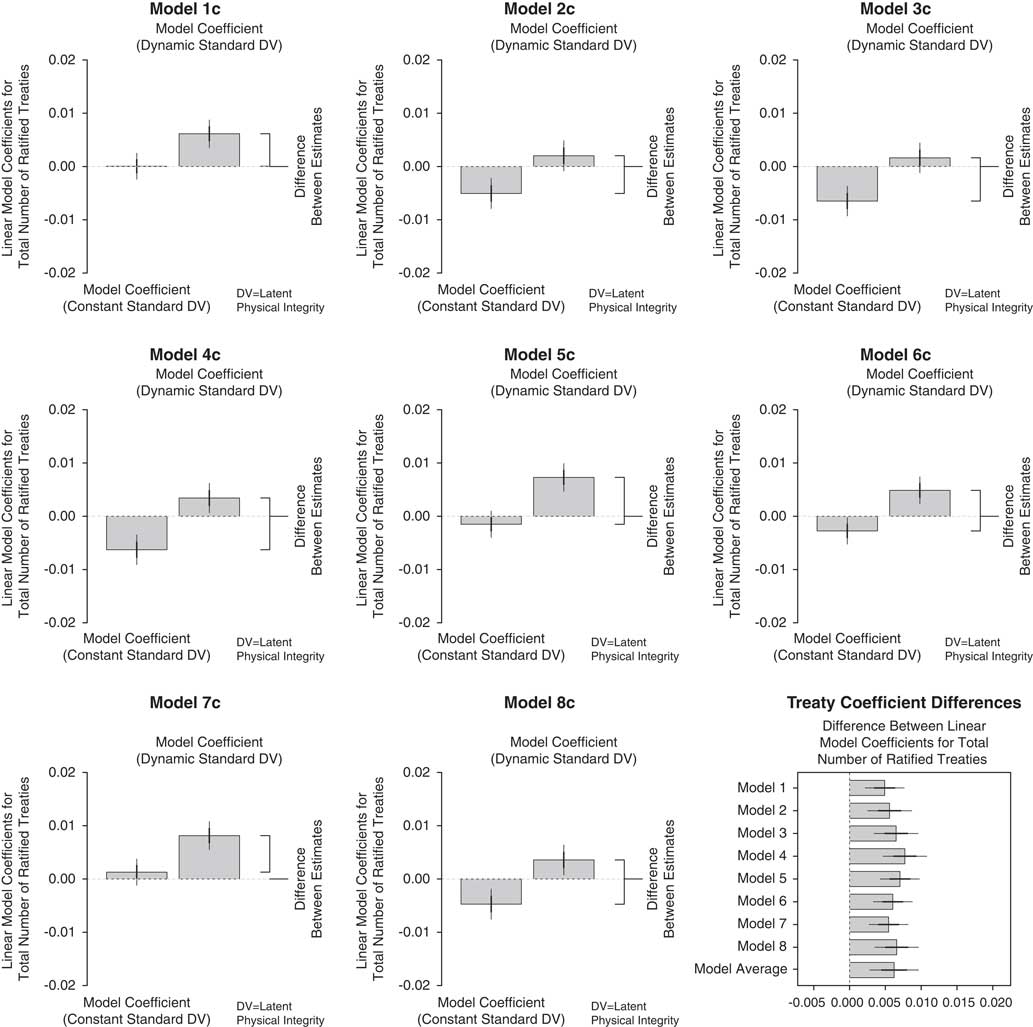

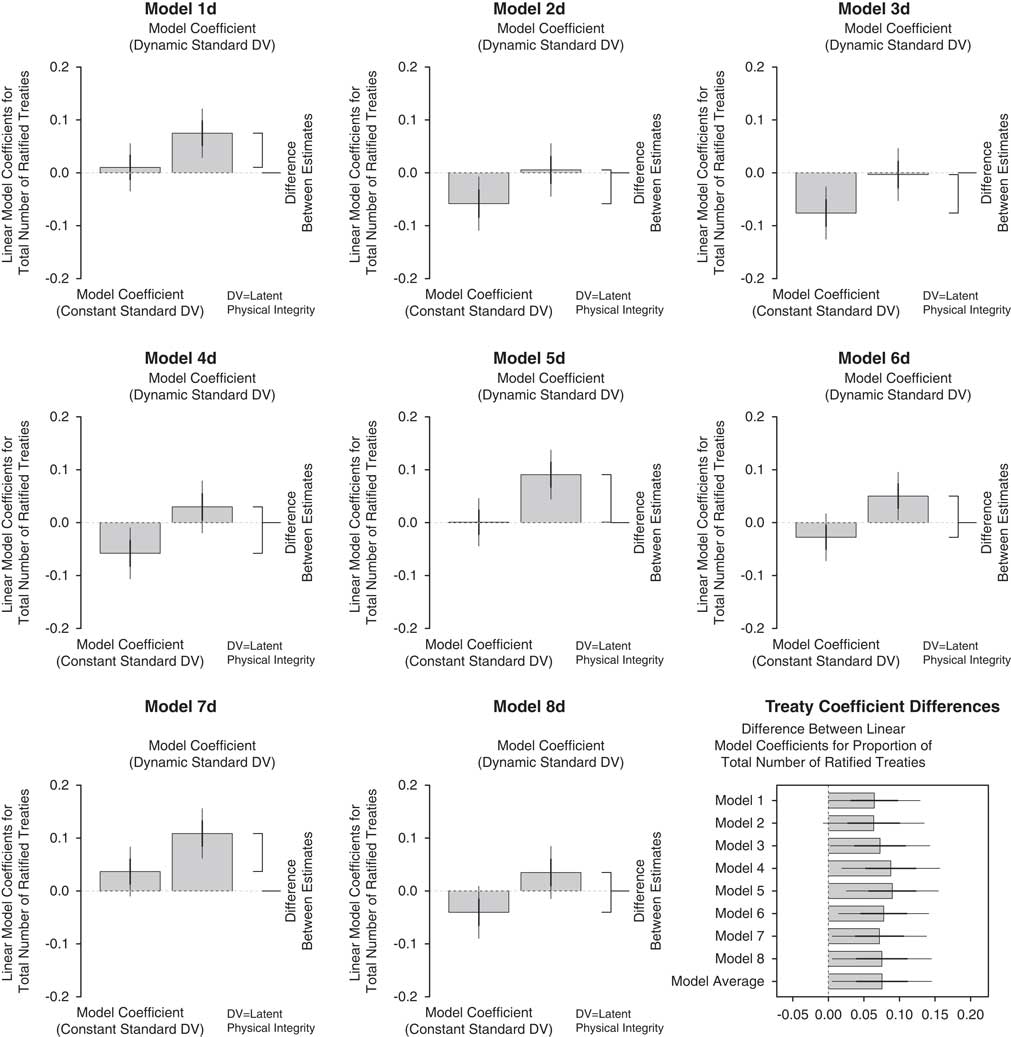

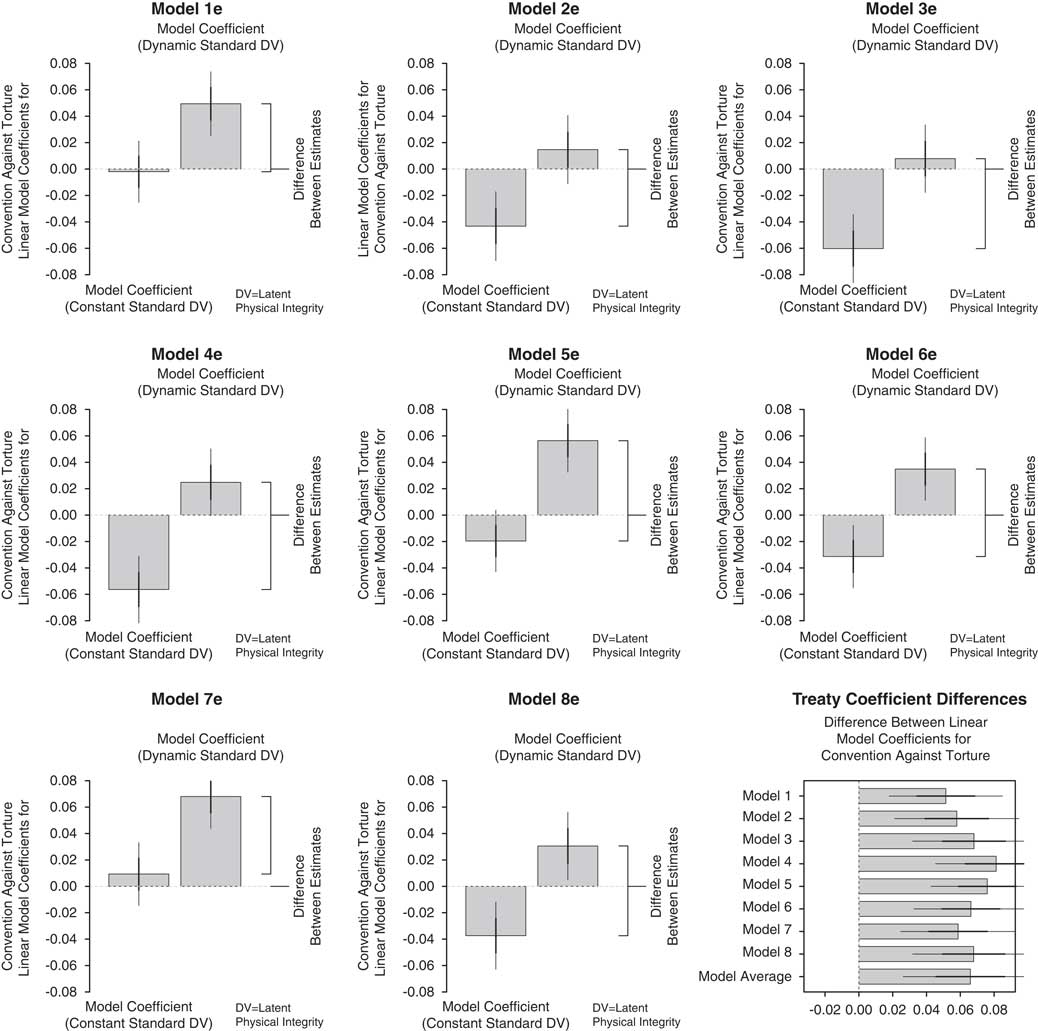

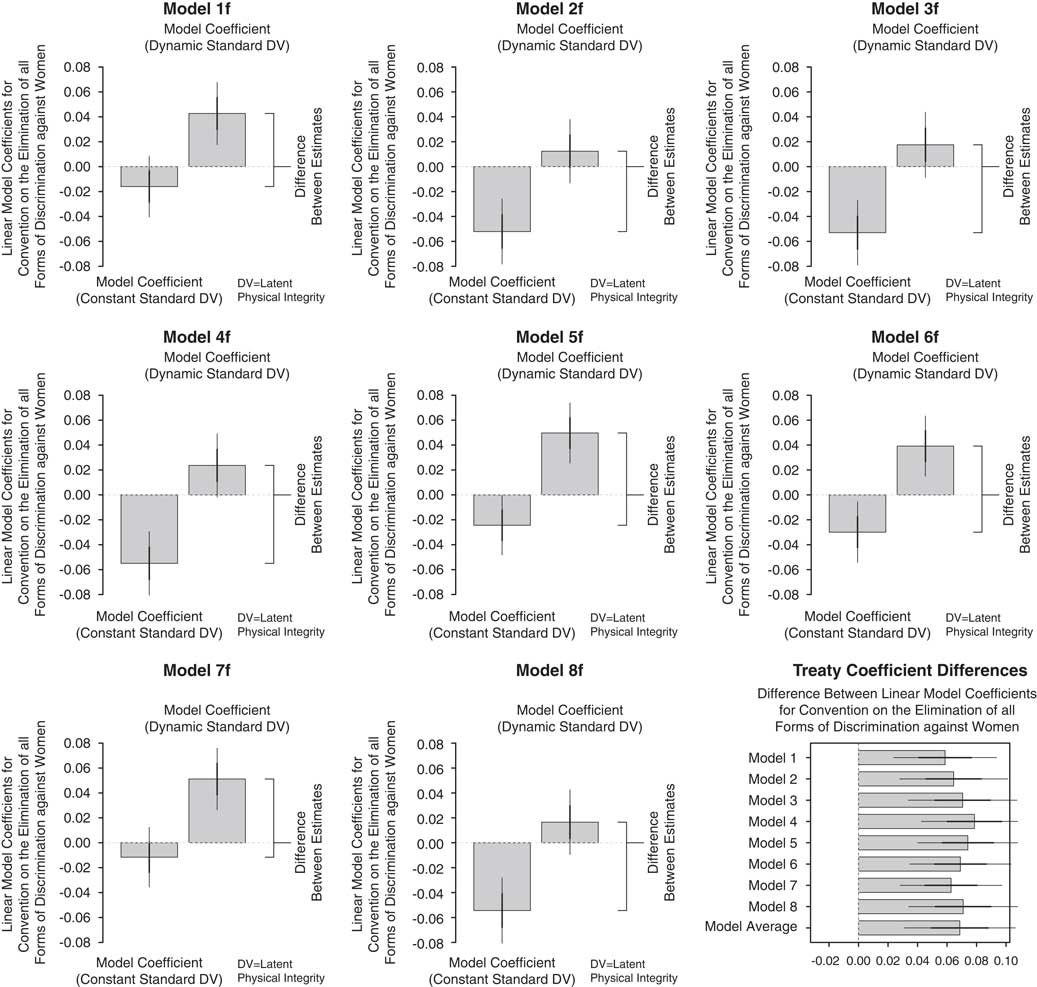

Overall, new relationships between treaty ratification and the level of human rights respect are obtained by replacing the dependent variable derived from the constant standard model with the one from the dynamic standard model, no matter what the specification of the regression model. Recall that the dynamic standard model accounts for the changing standard of accountability, while the constant standard model does not. For example, Figure 3 plots the linear model coefficient for the latent rights treaty variable. Again, each model uses one of the two latent physical integrity dependent variables and various control variables. Figures 4 and 5 display results using the two additive treaty scales. Figure 6 displays results using the treaty proportion variable. I also present visual results for the coefficients for the binary variable measures for the CAT, CEDAW, CCPR, CESCR, CRC, and CERD ratification variables respectively.Footnote 82

Fig. 3 Models for all human rights treaties using human rights latent treaty variable Notes for Fig. 3 : Estimated coefficient from the linear models using the dependent latent physical integrity variables from the constant standard model and the dynamic standard model respectively.The thick lines represent 1±the standard error of the coefficient. The thin lines represent 2±the standard error of the coefficient. The differences are all similar across models and all statistically different from 0. See the tables in Section F of the supplementary appendix for full model results.

Fig. 4 Models for selected human rights treaties (CAT, CCPR, CESCR, CERD, CEDAW, CRC), using human rights count treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

Fig. 5 Models for all human rights treaties, using human rights proportion treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

Fig. 6 Proportion of all human rights treaties available for ratification in year t, using human rights count treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

CONCLUSION

The results presented in this article represent a first step towards re-evaluating what has become conventional wisdom in the literature of international treaty compliance and human rights more generally.Footnote 83 I have presented evidence that the ratification of human rights treaties is empirically associated with higher levels of respect for human rights over time and across countries. This evidence bolsters claims that the negative correlations between variables measuring respect for human rights and variables measuring treaty ratification are an artifact of some other unaccounted for process.Footnote 84 With human rights data that now accounts for the changing standard of accountability, a new picture has emerged of improving levels of respect for human rights, which coincides with the increasing embeddedness of countries within the international human rights regime. This positive relationship is robust to a variety of measurement strategies and model specifications. These results are important because much of the theorizing in international relations begins with the premise that international human rights treaties are not effective in order to explain these puzzling, negative correlationsFootnote 85 or to provide policy recommendations based on these anomalous findings.Footnote 86 The results presented in this article, summarized in Table 3, cast considerable doubt on the empirical bases of these other research projects. Thus, conclusions and policy recommendations from this earlier research need to be re-evaluated.Footnote 87

Recent work by some human rights scholars has begun to unpack the institutional mechanisms by which international human rights treaty commitments can become effective.Footnote 88 With innovative new research designs availableFootnote 89 and now new data and measurement tools as well,Footnote 90 scholars have the ability to begin the systematic reassessment of the role that international human rights treaties play in mitigating the use of repressive tactics by all types of governments, working under a variety of institutional designs.

In closing, I wish to emphasize that a science of human rights requires valid comparisons of repression levels across different spatial and temporal contexts.Footnote 91 Scholars of human rights, repression, and contentious politics are aware of the fact that the quality of information across different political contexts is messy. Heterogeneity in information quality and the availability of information are major stumbling blocks for generating valid inferences about the topics our research community cares about. Latent variable models, with their focus on the theoretical relationship between data and model parameters, offer a principled way to bring together this information and make sense of it. This approach to measurement is useful because it shifts the burden of validity from the primary source documentation and raw data to the model parameters that bind these diverse pieces of information together.

Fig. 7 Models for the Convention Against Torture using binary treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

Fig. 8 Models of the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, using binary treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

Fig. 9 Models of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, using binary treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

Fig. 10 Models of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights, using binary treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

Fig. 11 Models of the International Convention on the Rights of the Child, using binary treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

Fig. 12 Models of the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, using binary treaty variable See Notes for Fig. 3.

Table 1 Global International Human Rights Instruments

Sources: (1): University of Minnesota Human Rights Library, http://www1.umn.edu/humanrts/

(2): United Nations Treaty Collections, http://treaties.un.org/

* The ‘Signed’ column refers to the year the treaty is opened for signature.

† The ‘Force’ column refers to the year the treaty enters into force.

Table 2 Summary of Visual Displays of Regression Results for Nine Treaty Variables

Note: Summary information for Figures 7–12 is contained in Table 2. Each figure displays linear regression coefficients for one of two dependent variables regressed on the selected treaty variable and controls. Each treaty variable is included in each of eight model specifications described above. The difference between the treaty coefficients is similar across model specifications for all treaty variables. To reiterate the results: even though the individual coefficients change depending on the model specification, the differences are consistent, which is a substantively important finding that eliminates concern that the use of a particular control variable is driving the results. And again, the results always contradict the negative findings from existing research. The coefficient for the each of the various treaty variables flip signs in every model permutation presented across the figures.

Table 3 Comparison of Results with Other StudiesFootnote *

* The findings presented in this study corroborate and strengthen the positive results present in many other recent studies that think carefully about research design strategies. These studies are presented in this table and discussed throughout the text of this article. Overall, the findings in these studies are strengthened because of the measurement issues addressed in this article. The negative results presented in other studies are likely only attributable to the systematic measurement bias caused by the changing standard of accountability. Several other studies report neutral results when exploring the relationship between the ratification of different treaties and respect for human rights (e.g. Keith Reference Keith1999). Again, the negative and neutral findings are most likely due to the unaccounted for changing standard of accountability implicitly contained in the data used in these earlier studies.

† Hill and Jones (Reference Hill and Jones2014) find both positive and negative correlations between treaty ratification and respect for human rights, which is why this study is listed in both columns of this table. Hill and Jones (Reference Hill and Jones2014) find positive relationships using the latent variable estimates that account for the changing standard of accountability developed by Fariss (Reference Fariss2014) but find negative relationships using the standard additive human rights scales (i.e., Cingranelli and Richards Reference Cingranelli and Richards1999; Cingranelli, Richards and Clay 2015a; Cingranelli, Richards and Clay 2015b; Gibney, Cornett and Wood 2012).