In representative democracies, politicians are sometimes forced to choose between actions that will further their political careers within a legislature or party and actions that will be popular with the public, and hence increase their chances of re-election. These choices are particularly complex in multilevel systems, in which politicians can pursue careers at either the regional or national level.Footnote 1 The career choices that legislators make, and the actions that follow from these choices, are central to the functioning of representative democracy; yet we know little about how political ambitions play out in multilevel contexts. In this article, we argue that the effect of individual ambition on legislative behavior is crucially shaped by the electoral system, which influences inter alia whether politicians have incentives to cater primarily to actors who control candidate selection (either locally or centrally), or primarily to voters in their constituencies. Hence there is a trade-off, conditioned by electoral institutions, between dedicated and professional legislators, on the one hand, and politicians who are visible and accountable to their electorates, on the other hand.

To investigate how electoral institutions moderate the relationship between career ambitions and legislative participation in a multilevel political system, we take advantage of the variation in electoral rules governing European Parliament (EP) elections and examine the career ambitions and behavior of Members of the European Parliament (MEPs). We posit that politicians seeking political career progression at either the state or federal level carefully adjust their legislative participation to increase their chances of promotion at their preferred level of government. Such personal ambitions are moderated by the structural incentives of the electoral system.Footnote 2 In a ‘candidate-centered’ electoral system, such as open-list proportional representation, legislators who want to be re-elected need to devote greater attention to their constituency regardless of which office they are seeking. Once a high profile has been established locally, this lowers the cost of transferring from one political arena to another. In contrast, in a ‘party-centered’ electoral system, such as closed-list proportional representation, legislators primarily need to be on good terms with their party leaders, who control candidate selection. The effect of career ambition on legislative participation thus varies across electoral systems. Politicians in candidate-centered systems are likely to be less willing to spend time on legislative activities, particularly if they seek a career at a different electoral level, as they have a greater need to spend time developing a constituency profile. In contrast, in party-centered systems, politicians who aim to further their career can afford to focus more on legislative activities since their party, not their constituency, matters most for their career advancement at both the regional and national levels.

We test these propositions using original data on MEPs’ career ambitions, both ‘stated’ and ‘realized’. We employ data from surveys of MEPs to identify their ‘stated ambitions’, as well as data on post-parliamentary careers to identify their ‘realized ambitions’. The EP is a useful laboratory in which to investigate these issues, because the same set of politicians in a single legislature is elected under different electoral systems in each European Union (EU) member state. Also, because the EP is a low-salience legislature, a large proportion of politicians harbors ambitions to return to national politics. Our findings show that these career ambitions have a substantive effect on legislative participation in candidate-centered systems, causing those MEPs with national-level ambitions to participate substantively less. The career-ambition effect is weaker in party-centered systems. Importantly, this suggests that candidate-centered systems, which are generally seen to encourage politicians to be more responsive to voters, can reduce the quality of legislative decision making, at least in low-salience legislatures.

The remainder of the article is organized as follows. We first situate our contribution to the literature on the career ambitions of politicians in multilevel systems, legislative behavior and electoral institutions, before presenting our theoretical argument and hypotheses concerning how electoral institutions condition the effect of career ambitions on legislative participation. We subsequently introduce the data and methods we use in the analysis, before presenting the results. The conclusion discusses the wider implications of our findings.

CAREER AMBITIONS, LEGISLATIVE BEHAVIOR AND ELECTORAL RULES

Legislators have different ambitions about their future careers.Footnote 3 Some may wish to remain for multiple terms in the same legislature, some will aspire to higher office, while others may wish to leave politics altogether. Such political ambitions shape the choices legislators make in their current positions. As Schlesinger noted in his seminal book, Ambitions and Politics, ‘a politician’s behavior is a response to his office goals’.Footnote 4 To achieve these goals, a politician must adapt his behavior to satisfy not only current constituents, but also potential future constituents: ‘our ambitious politician must act today in terms of the electorate he hopes to win tomorrow’.Footnote 5 Several studies have applied and extended the basic tenet of this ‘ambition theory’ in the US context.Footnote 6 Hibbing’s study of legislative behavior in the US House of Representatives, for example, confirms that politicians behave with an eye toward the constituency they hope to serve tomorrow.Footnote 7 He demonstrates that representatives who want to trade constituencies change their behavior before the contest for the new constituency is held. The key conclusion from this literature on political ambition and legislative behavior is that we cannot simply treat legislators as ‘single-minded re-election seekers’ in their current career positions. Rather, the behavior of many legislators will be shaped by the specific political constituency they hope to serve in the future.Footnote 8

Most studies assume that political careers are hierarchically organized, from the local, to the regional (state), to the national (federal) level. In the US context, for example, research has shown that politicians have ambitions to ‘move upwards’ from the state level to the federal level, and that the state and federal levels of government provide different incentives and rewards for politicians.Footnote 9 Nevertheless, career paths in other countries are often less clear-cut. Studies of political careers in federal systems have shown that while many politicians aspire to ‘move up’, others see their regional or state office functions as the main focus of their careers.Footnote 10

Previous studies have found that the political ambition of Brazilian legislators focuses on the subnational (municipal and state) level.Footnote 11 Yet, in line with ambition theory, Samuels demonstrates that even while serving in the national legislature, Brazilian legislators act strategically to further their future extra-legislative careers by serving as ‘ambassadors’ of subnational governments. Similarly, Carey finds that Costa Rican legislators, who are constitutionally restricted to a single term in the national legislative assembly, compete to align themselves with key party leaders, who are best placed to help them secure a post-legislative administrative appointment.Footnote 12 In a European context, Stolz points to integrated career paths at the regional and federal levels for Catalan politicians, whereas there are distinctly alternative career paths in Scotland.Footnote 13

Hence, in multilevel systems it is useful to distinguish between (1) a progressive ambition, which implies that a legislator seeks to leave his or her current legislative chamber and move to a another level of government (without assuming uni-directionality) and (2) a static ambition, which implies that a legislator wishes to build a career within his or her current legislature.Footnote 14 Depending on the institutional context, the predominant ambition among legislators may be static (seeking re-election) or progressive, seeking to move either ‘up’ from the state level to the federal level (for example, in the United States), ‘down’ from the federal to state/subnational level (for example, in Brazil), or ‘across’ between the regional and federal levels (for example, in Catalonia).

We argue that to understand how such ambitions shape legislative behavior in multilevel systems, electoral institutions are a key conditioning variable. It is well known that electoral systems shape how politicians campaign and how they behave once elected, such as how responsive they are to legislative party leaders or which legislative committees they choose to join.Footnote 15 We know far less about how electoral rules moderate the effect of career ambitions on legislative behavior. Previous studies have touched on this question. For example, Cox, Rosenbluth and Thies and Pekkanen, Nyblade and Krauss examine how variations in electoral rules moderate the effect of career ambitions on factionalism in the Japanese Diet.Footnote 16 Similarly, Jun and Hix find that the structure of candidate selection in South Korea shapes the individual parliamentary behavior of legislators.Footnote 17

Where career incentives are concerned, one key aspect of the electoral system is the difference between ‘candidate-centered’ and ‘party-centered’ systems.Footnote 18 In candidate-centered systems, the ballot structure allows voters to choose between candidates from the same political party, as in open-list proportional representation systems or under single-transferable vote. In party-centered systems, in contrast, the ballot structure only allows voters to choose between pre-ordered lists of candidates presented by parties, as in closed-list proportional representation systems.Footnote 19

In candidate-centered electoral systems, legislators who want to be elected need to develop their name recognition among voters in their constituency regardless of which office they aspire to. Career prospects in a candidate-centered electoral system therefore depend in large part on the candidate’s ability to cultivate personal identification and support within the electorate. For legislators who want to continue their political career in the current institution, low participation rates may be an electoral liability. But for politicians elected under candidate-centered electoral systems, any potential electoral cost of campaigning rather than participating, and hence appearing to shirk from one’s legislative responsibilities, would be heavily outweighed by the positive benefits of raising one’s profile among the voters.

This argument is in line with formal work, such as Ashworth’s model of how legislators trade off legislative participation vis-à-vis constituency services under different legislative arrangements.Footnote 20 One implication of this model is that legislators devote relatively more effort to constituency activities if voters can distinguish between support for a party and support for an individual candidate at the ballot box. Moreover, this trade-off in favor of campaigning over legislative participation is likely to be higher for legislators seeking a career in another legislative arena than for those seeking to continue in their current arena, since for the latter group low legislative participation may be seen as a liability. In a party-centered electoral system, by contrast, it is usually sufficient for the legislator to be on good terms with the party leaders who control candidate selection to keep his or her position.Footnote 21 We now turn to how electoral rules and career ambitions interact to shape legislative behavior in the multilevel context of the EU.

PARTICIPATION, AMBITIONS AND ELECTORAL RULES IN THE EP

The EU is a pertinent example of multilevel career paths. As in other legislatures in multilevel systems, MEPs typically follow one of three career paths: some advance within the EP itself, others see the EP as a stepping stone to a more coveted legislative or executive position in their home country, and a third group leaves politics altogether or retires. The key contrast is between the first two types of MEPs: (1) those who have static ambitions, and seek to build a career in Brussels and (2) those who have progressive ambitions, and seek a career ‘back home’.Footnote 22 For example, Daniel finds that as the powers of the EP have grown, which has coincided with the increased professionalization of the chamber, the proportion of MEPs who have a static career ambition (and hence seek re-election to the EP) has also grown.Footnote 23 Politicians with these static ambitions need to undertake tasks that are important to party leaders inside the EP in order to increase their prominence within the institution. However, these politicians also need to please those who control their re-selection and re-election, who tend to be located at the national level.Footnote 24 These national selectors prefer to re-nominate MEPs, everything else equal.Footnote 25

In contrast, politicians who seek to move to the national arena are less concerned with developing their prominence within the EP. Instead, their key concern is to make it plausible that they are capable of conducting tasks associated with holding national office, such as being visible in the national media and cultivating ties with the national leadership in order to secure an attractive post if successful at entering national politics. Hence the focus of politicians with progressive career ambitions will not be on pleasing those who control promotion inside the EP or re-selection/re-election to the EP. Instead, their primary interest will be to cater to the gatekeepers of political office at the national level. Indeed, work on career ambition in the EP has shown that MEPs who aim to return to national politics are more likely to vote against their legislative party groups and oppose legislation that enhances the power of the EU’s supranational institutions. Using age as a proxy for career ambition, Meserve, Pemstein and Bernhard find that MEPs with progressive career ambitions (younger) are more likely to vote against their European political groups than (older) MEPs with static career ambitions.Footnote 26 Similarly, Daniel finds that more senior MEPs, who have had a longer static career in the EP, are more likely to win ‘rapporteurships’ (legislative report-writing positions).Footnote 27

To identify the interaction between electoral rules and career ambitions in shaping legislative behavior in the EU, we focus on one particular aspect of legislative behavior: legislative participation. Participation can be regarded as a pivotal indicator of a legislator’s ‘valence’ (for example, his or her quality, commitment or diligence).Footnote 28 Conversely, absenteeism and low involvement in legislative activities can be seen as signs of shirking.Footnote 29 Participation may also influence legislators’ chances of re-election. However, the personal valence of politicians plays a less significant role in electoral competition for seats in lower-salience legislatures, such as regional or state legislatures, since the lack of media attention to these bodies makes it far harder for voters to monitor and sanction the behavior of their members. This is relevant in our context given that for voters, parties and candidates, elections to national political office are more highly valued and more salient than elections to the EP.Footnote 30

Of course, career ambitions are not the only motivation that guides legislative behavior. Legislators are also policy seekers who are driven to participate to fulfill certain policy goals.Footnote 31 Yet, all other things being equal, we expect that career ambitions are an important factor shaping parliamentary behavior. Consistent with the existing literature on careers and legislative behavior, we thus argue that legislators optimize their behavior to further their career goals.Footnote 32 There are competing demands on legislators’ time, such as scrutinizing legislation, constituency service, participation in public debates and work in the party organization.Footnote 33 Moreover, because each of these activities matters more to some voters and candidate selectors than others, legislators need to engage in the optimal combination of activities to maximize their chances of reaching their career goals. Specifically, for a legislator to be trusted with an office, he or she needs to make the case to the key gatekeepers of that office that he or she is capable of conducting the tasks of the office in an appropriate manner and in the interests of the gatekeepers.

Here, electoral institutions come into play. Despite Europe-wide ‘direct’ elections to the EP since 1979, and repeated efforts to establish a uniform electoral system, there is still considerable discretion for each member state to determine its own precise rules for electing MEPs (as long as a proportional electoral system is used). Where the ballot structure is concerned, about half of the EU’s states uses a candidate-centered system (either open-list proportional representation or single transferable vote), while the other half uses a party-centered system (closed-list proportional representation). In most of the states that use party-centered electoral systems, the central party leaderships draw up the candidate lists. Even in the two states with party-centered systems and regional constituencies – France and the United Kingdom – the central party leaderships influence the order of the lists, by deciding whether candidates can re-stand in the elections and formally approving any new candidates.

Within party-centered electoral systems, in which the party has considerable influence over individual MEPs, a legislator’s active involvement in parliamentary activities has a positive influence on his or her career prospects at the European level. The national party is more likely to want to re-select an MEP for a seat in the EP if she has actively participated in legislative activities. Equally, an MEP who has her heart set on a second or third term in Brussels is more likely to prioritize legislative activities inside the Parliament if she knows that the relevant gatekeepers are watching. While the party leaderships will take notice of politicians’ activity levels, because of the low salience of EP elections, voters are largely ignorant of the day-to-day activities of MEPs. However, while voters pay limited attention to activities in the EP, research has shown that candidate characteristics and campaign activities may influence their re-election chances.Footnote 34

Given that candidates’ career prospects hinge on the party leadership in party-centered systems, we would expect MEPs who have ambitions to stay at the European level to be far more engaged in legislative activities in the EP. Moreover, politicians who would like to progress to the national level can still spend time in the legislature, as long as the national party leadership supports their move to national-level politics, since national party leadership support is sufficient for a successful transition to national politics (assuming that electoral support for the party does not collapse).

In contrast, the career prospects of a politician in a candidate-centered electoral system depend to a greater extent on the candidate’s ability to cultivate personal identification and support within the electorate. Hence, there are fewer incentives for politicians elected in such systems to participate in legislative work in their current legislature, particularly if they seek to continue their career at another level. We therefore expect more distinct differences in legislative participation between legislators with national-level ambitions in candidate-centered systems, and a clearer distinction between politicians with static and progressive career ambitions in party-centered systems.

This leads us to the following hypotheses about career ambitions and legislative participation in multilevel systems, and about the moderating effect of the electoral system on the relationship between career ambitions and participation.

Hypothesis 1: Politicians with (static) European-level career ambitions are more likely to participate than politicians with (progressive) national-level career ambitions.

Hypothesis 2: The difference in participation attributed to differences in career ambitions is more pronounced in candidate-centered than in party-centered electoral systems.

In the next section, we discuss the data and methods that allow us to test these hypotheses.

DATA AND EMPIRICAL ESTIMATION

As discussed, the EP provides an excellent case for investigating these propositions because multiple electoral systems operate within the same institutional setting. Although legislation on the uniformity of electoral procedures in EP elections was enacted in 2003 (which requires all elections to the EP to be held under a proportional electoral system), there continues to be considerable variation in the ballot structure, district magnitude and candidate selection rules across EU member states. There are some within-country differences in electoral systems applied for EP and national parliamentary elections, in particular after the unification of the EP electoral rules.Footnote 35 However, these differences are not consequential for classifying an electoral system as candidate or party centered.

A further strength of our study is that we examine the effect of our primary explanatory variable, career ambition type, using two unique indicators of both ‘realized’ and ‘stated’ ambitions. Previous research on ambition has relied on proxies, such as age, to measure MEPs’ ambition.Footnote 36 We employ actual measures of stated career ambition, using survey data on MEPs’ future ambitions, as well as realized ambition, using observed data on MEPs’ actual careers. The advantage of the former measure is that it captures subjective ambitions prior to legislative participation for a subset of MEPs, whereas the advantage of the latter measure is that it provides actual biographical data on all MEPs in the period under investigation. In combination, these measures provide a rigorous test of the effect of ambitions on legislative behavior.

To achieve this, our empirical analysis focuses on 2,094 MEPs who were elected to serve in any period between the 4th and the 7th sessions of the EP (1994–2014), since this allows us to obtain good-quality data on pre-EP careers and ambitions as well as post-EP careers. As several MEPs served in more than one term, we have 3,341 observations in total. In line with previous work, we distinguish between three types of career ambitious amongst MEPs: national (progressive), European (static) and non-political careers.Footnote 37 For data on post-EP careers (realized ambition), we conducted a systematic search, consulting a range of online resources, such as the official webpage of the EP and national parliaments, webpages of European and national parties and individual politicians, complemented by EU Who is Who. We classified post-EP careers as: (1) National political career, (2) European political career or (3) Non-political career. The national political career category includes MEPs who went on to become members of the national parliament or national cabinet, either within a year (post-EP career) or at some point within the following five years (within five years career). The European political career category includes MEPs who remained members of the EP or became European commissioners. All others are classified as having a non-political career or retired. To capture ‘stated’ career ambitions we used survey data on MEPs collected in 2000, 2005 and 2010.Footnote 38 This allows us to compare stated and realized ambitions for a subset of the MEPs who responded to the survey. The survey question was worded as follows:

What would you like to be doing 10 years from now? (Choose as many boxes as you wish)

∙ Member of the European Parliament

∙ Chair of a European Parliament committee

∙ Chair of a European political group

∙ Member of a national parliament

∙ Member of a national government

∙ European Commissioner

∙ Retired from public life

∙ Something else, please specify.

The three surveys yielded a total of 727 respondents. Since some MEPs participated in the surveys in several Parliaments, the dataset includes 591 individual MEPs. The survey respondents were not significantly different from the population of MEPs on key variables, such as European political group, member state and gender.Footnote 39 Respondents who answered ‘Member of the European Parliament’, ‘Chair of a European Parliament committee’, ‘Chair of a European political group’ or ‘European Commissioner’ as seeking a European-level career. MEPs who answered ‘Member of a national parliament’ or ‘Member of a national government’ are coded as seeking a national-level career.

To measure our dependent variable, we consider two types of legislative participation: voting, and speeches in debates. Voting and speeches are the two main activities in which legislators engage in the plenary sessions, and have been the subject of numerous studies.Footnote 40 For these two types of behavior we look at two different ways of measuring participation. When considering voting participation, we look at all roll-call votes as well as participation in at least one vote on a given day in which at least one roll-call vote was requested. We use all data from twenty years of voting and attendance records, from 1994 to 2014 (EP4 to EP7). Some concerns have been raised that findings based on roll-call votes in the EP may be biased, as they do not represent a random sample of all votes. In particular, many roll-call votes are taken on non-binding, and lopsided, resolutions.Footnote 41 But as we rely on both voting and attendance records, our results should be less sensitive to such bias. In Appendix Tables A2 and A3 we repeat the analysis on legislative votes and close votes (in which the difference between Yes and No was less than 100). Also, as there may be substantive differences across national parties, Table A1 reports the results from models with national party and legislative term random intercepts. All these results are in line with those presented in the Results section.

Similarly, for participation in plenary debates, we consider all speeches by an MEP, given all speeches made during the time the MEP served, as well as the number of days with plenary debates in which an MEP participated at least once, given all days he or she could have participated. Proksch and Slapin provide a comparative analysis of participation in debates, demonstrating that there is variation in party leadership control by electoral institutions, arguing that in candidate-centered systems, constituency-based critiques of the policies of the party leadership are more welcomed.Footnote 42 Due to the availability of debates in an electronic format, we are limited in our analysis to the most recent fifteen years, 1999–2014 (EP5 to EP7).

To test our second hypothesis we need to operationalize the key moderating variable: the electoral system. As discussed, the most important distinction for our purpose is between candidate- and party-centered systems, which concerns the degree to which the ballot structure allows voters to determine the fate of individual candidates. In the main models, we follow Farrell and Scully, supplemented by our own reading of the electoral rules in the 2009 elections. We classify closed-list proportional representation as party-centered, and single-transferable vote, open-list proportional representation and single-member plurality as candidate centered.Footnote 43 To ensure that the career effect holds within the different systems, we also run a model in which the effect of career ambitions is analyzed separately for each type of electoral system. In order to capture how electoral institutions shape behavior through the re-election incentives they create, rather than the selection effects, we consider the prospective system in which an MEP is likely to run in the next election, not the system in which he or she was elected. The distribution of MEPs by career ambition and electoral institutions is presented in Table 1.Footnote 44

Table 1 Career Ambitions by Electoral Institution

Note: party-centered systems: Belgium, Czech Republic, France, Germany, Greece (–2009), Hungary, Latvia, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and United Kingdom. Candidate-centered systems: Austria, Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, Greece (2014), Estonia, Ireland, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta and Sweden.

The table shows that most MEPs are elected in party-centered systems, and that there is a higher proportion of MEPs with national-level political ambitions in candidate-centered systems. But in these systems there are also relatively more MEPs who plan to leave politics. This suggests that there may be a difference in who becomes an MEP across the two systems.

RESULTS

We begin our analysis of participation in roll-call votes with a simple comparison of participation levels given career ambition, conditional on the type of electoral institution.

Table 2 shows that those who seek to continue as an MEP participate more than both those who seek a career at the national level as well as those who seek to leave politics. Also, MEPs who seek a national-level career participate least. This holds for both candidate- and party-centered systems. Also, within career ambition types, MEPs from party-centered systems participate more. In Table 3, we show that this pattern holds when we consider presence in the EP, as measured by participating in at least one roll-call vote per day. However, here we notice that the difference between those who seek to stay on and those who leave politics is smaller.

Table 2 Participation in Roll-Call Votes by Career Ambition, Conditional on Electoral Institution

Note: proportion of roll-call votes participated in, out of all roll-call votes in the period each MEP served.

Table 3 Participation by Career Ambitions, Conditional on Electoral Institution

Note: proportion of days that MEPs voted in at least one roll-call vote, out of all days with roll-call votes in the period each MEP served.

In Table 4, we present the results from a more sophisticated statistical analysis. The statistical models are hierarchical binomial, taking the number of votes cast (Model 1 and 3), or active voting days (Model 2), given the number of total votes (Models 1 and 3) or total voting days (Model 2) as the dependent variable. Our explanatory variables are the combinations of career ambition and electoral institutions. We control for background in national politics, incumbency in the EP, age, and leadership roles in the committees and the European political groups. We also include political group, member state and legislative term specific intercepts. In Model 3, we include electoral systems rather than the binary candidate- vs. party-centered system. Note that the inclusion of intercepts for political groups, member states and parliamentary terms allows us to average over differences across countries, political groups and over time.Footnote 45

Table 4 Hierarchical Binomial Models: Participation in Roll-Call Votes

Note: hierarchical binomial models with random intercept for political groups, member states and parliamentary term. Dependent variable: participation in roll-call votes (all, daily, all). Estimates are posterior mode and 95 per cent posterior probability intervals. CLPR = closed-list proportional representation; OLPR = open-list proportional representation; SMP = single-member plurality; STV = single-transferable vote.

We see that the patterns from the bivariate analysis hold even when controlling for other variables, such as political group, member state and legislative term. In line with our hypotheses, we see that career ambition matters for participation in votes. MEPs with national career ambitions participate less than those with European-level career ambitions. The reference category is European career ambitions in a party-centered system. In Model 1, we see that the difference in participation as a function of career ambition is larger in candidate-centered systems than in party-centered systems. However, in Model 2, in which we only count participation in at least one vote per voting day, the difference across electoral institutions is harder to detect. This is in line with the pattern we would expect to see if MEPs with national career ambitions from candidate-centered systems were more likely than other MEPs to either arrive late or leave early in order to attend extra-parliamentary events in their constituencies. This finding is supported by a recent study that demonstrates that electoral institutions impact MEPs’ Twitter outreach strategies. Notably, these other results show greater social media activity by MEPs in candidate-centered systems.Footnote 46

In Model 3, we depart from the binary distinction of candidate- vs. party-centered systems to investigate the differences in behavior as a result of career ambitions within each system. The reference category here is MEPs with national career ambitions in open-list proportional representation systems. In line with our first hypothesis, career ambitions matter for participation in votes across all systems. Within each electoral system, MEPs with national-level career ambitions participate in fewer votes than those with European-level ambitions. The pattern holds within each type of electoral system.

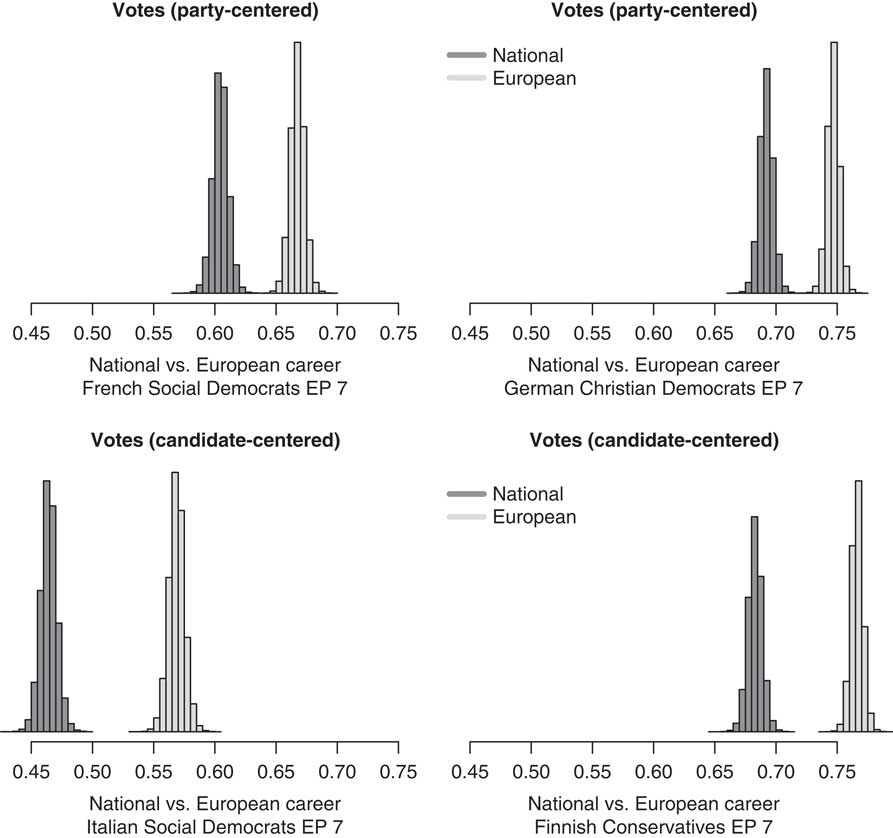

In Figure 1, we illustrate the substantive moderating effect of electoral institutions given career ambition on participation in votes in EP7 (2009–14). As examples of MEPs from party-centered systems, we selected French Social Democrats (P&S) and German Christian Democrats (EPP). These are presented in the top row of the figure. As examples of MEPs from candidate-centered systems, we selected Italian Social Democrats (P&S) and Finnish Conservatives (EPP). These are presented in the bottom row. Two aspects are clear from the figure. First, the difference in the level of participation is substantively larger in candidate-centered systems than in party-centered systems. Also, the level of participation varies across countries within these two types of systems. For example, French MEPs participate less than German MEPs, and Italian MEPs participate less than their Finnish counterparts. Daniel links such differences between member states with similar electoral institutions to differences in the party systems.Footnote 47 This is an interesting suggestion, but outside the scope of this article, which focuses on the effect of electoral institutions on career ambitions.

Fig. 1 The moderating effect of electoral institutions given career ambition on voting

PARTICIPATION IN DEBATES

Next, we investigate the extent to which we can find a similar pattern for parliamentary debates. We begin by investigating aggregate differences in mean participation rates across electoral institutions and career ambitions in Table 5. As with votes, we see that MEPs with European career ambitions participate more than those with national career ambitions.

Table 5 Participation in Plenary Debates, by Career Ambition, Conditional on Electoral Institutions

Note: proportion of days with debates MEPs participated in, out of all days with debates in the period each MEP served.

In Table 6 we run a similar set of models, but using debates instead of votes as our dependent variable. In Model 4 the dependent variable is the number of speeches out of all speeches occurring during the MEP’s tenure. In Model 5 we use the number of days an MEP participated in a debate relative to all the days with debates during the MEP’s time in office. Model 6 replicates Model 4, but using electoral systems interacted with career ambitions.

Table 6 Hierarchical Binomial Models: Participation in Debates

Note: hierarchical binomial models with random intercept for political groups, member states and parliamentary term. Dependent variable: participation in debates (all, at least once that day, at least once that day). Estimates are posterior mode and 95 per cent posterior probability intervals. CLPR = closed-list proportional representation; OLPR = open-list proportional representation; SMP = single-member plurality; STV = single-transferable vote.

The key results are consistent with those reported in the previous subsection, on votes. MEPs with national career ambitions participate less than those with European career ambitions. When we count all speeches, the difference is larger in candidate-centered than in party-centered systems. Again, this difference disappears if we use the number of days with a speech (Model 4) instead of the number of speeches (Model 5), which is consistent with these MEPs missing part of the plenary sessions due to engagements outside the chamber, which forces them to leave early or arrive late more often than their counterparts in party-centered systems. Also, in Model 6, we see that higher participation for MEPs with European career ambitions than those with national career ambitions holds in every pair of electoral systems.

The patterns in the control variables are consistent across model specifications. Political experience, at both the European and national levels, is associated with more plenary speeches. In contrast, there is a negative correlation between age and participation in plenary debates. Unsurprisingly, both the group and committee leaders speak more often during the plenary sessions than ‘backbenchers’.

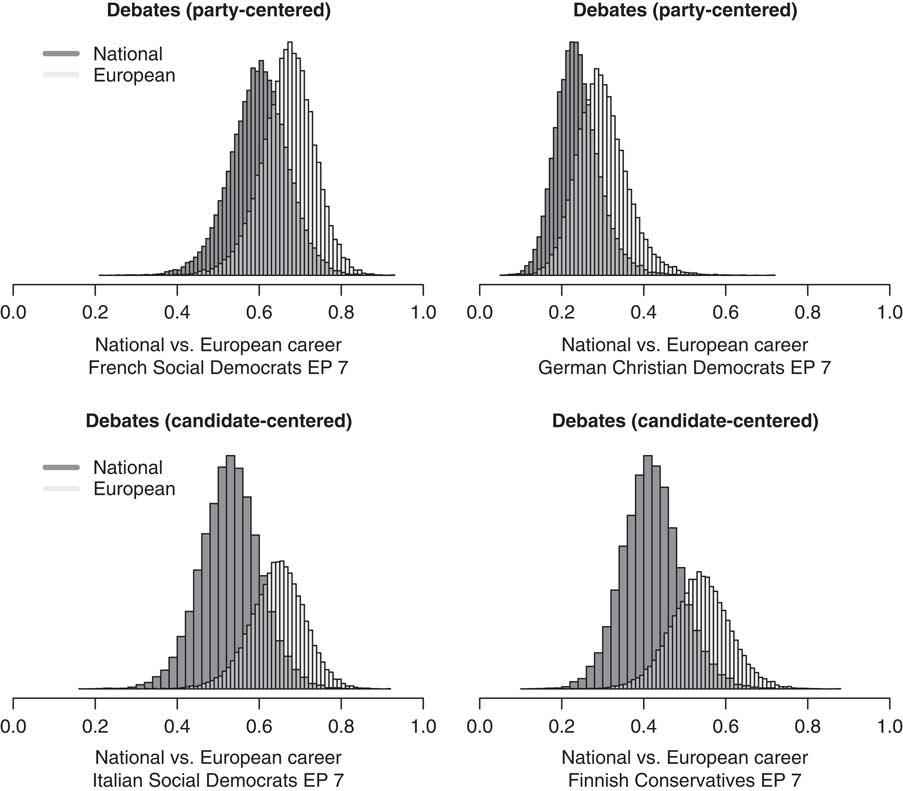

In Figure 2, we compare participation in debates across electoral institutions, using the same examples as above. While we see that there are smaller substantive differences by career ambitions, we nevertheless notice a distinct difference between party- and candidate-centered systems. In the latter, we are able to detect two different peaks in the distribution. MEPs with European-level career ambitions tend to participate more than those with national-level ambitions in candidate-centered systems. There is hardly any detectable difference in party-centered systems.

Fig. 2 The moderating effect of electoral institutions given career ambition on speeches

STATED CAREER AMBITIONS

Finally, we evaluate the extent to which we find similar patterns when considering ‘stated’ rather than ‘realized’ career ambitions. The descriptive relationship between career ambitions and votes is presented in Table 7, and the results for debates are presented in Table 8.Footnote 48 The tables show that for participation in both votes and debates, MEPs who seek a long-term European career participate more. Also, the difference in participation by career ambition is larger in candidate-centered systems than in party-centered systems.

Table 7 Survey: Future Career, Electoral Institutions and Participation in Votes

Note: proportion of days with roll-call votes that MEPs voted in at least one roll-call vote, out of all days that held roll-call votes in the period each MEP served.

Table 8 Survey: Future Career, Electoral Institutions and Participation in Debates

Note: proportion of days with debates MEPs participated in, out of all days with debates in the period each MEP served.

These descriptive results are encouraging, and Table 9 investigates whether the patterns also hold in a more sophisticated model. For the survey-based career ambition variable, we show the correlation between career ambitions and participation in roll-call votes in Model 7. Then, in Model 8, we focus on debates. We use the same control variables and structure as in the previous models – that is, member state, political group and legislative term random intercepts. As above, we control for previous experience, age, and leadership roles in the political groups and committees.

Table 9 Results for Stated Ambitions: Votes and Speeches

Note: hierarchical binomial models with random intercept for political groups, member states and parliamentary term. Dependent variable: participation in roll-call votes (Model 7) and in debates (Model 8). Estimates are posterior mode and 95 per cent posterior probability intervals.

The patterns from the ‘stated’ survey results are similar to the above results that relied on ‘realized’ career ambitions. Career ambitions matter for participation, especially in candidate-centered systems. MEPs seeking to move to the national arena participate less than those who want to stay on in the EP. The effect of career ambitions on participation is greater in candidate-centered systems than in party-centered systems.

For the control variables, the patterns are as expected. The MEPs who said that they planned to leave politics tended to have higher participation rates than those who were aiming for a national career, but lower participation rates than MEPs who planned to stay on in the EP. Political experience, both national and European, is associated with lower participation in votes but higher participation in speeches. Older MEPs, for whatever reason, vote more, but are less likely to speak. Unsurprisingly, political group leaders participate in more votes and speak more often than backbenchers. Committee chairs (and vice chairs) are more active than backbenchers across both types of participation.

Finally, Figure 3 shows the substantive effects of stated career ambitions, given electoral institutions. We illustrate the effect with French and Italian Christian Democrats in EP7 (2009–14). We see that there is a substantively larger difference in participation as a function of stated career ambitions among Italian MEPs than among French MEPs. When we compare across activities, we see the same pattern for both stated and realized preferences. The career effect is largest when access to the activity is not scarce (in votes). Alternatively, making speeches may be very valuable to MEPs from party-centered systems, as it may be an opportunity for individual MEPs to demonstrate their level of policy expertise to their party leadership, and thus to increase their chances of being re-elected.

Fig. 3 The moderating effect of electoral institutions given career ambition on votes and speeches (survey)

These results show a clear and consistent pattern in the case of participation in both voting and debates. Our key findings can be summarized as follows. MEPs with national-level career ambitions participate less than those who seek a European-level career. The difference is larger in candidate-centered systems. This holds for both realized and stated career ambitions. This pattern is strongest when participation is not a scarce good, such as in voting. In other words, the fact that one MEP is participating in a vote does not reduce the opportunity for other MEPs to participate in that vote. In contrast, making a speech is a scarce good, as speaking time is limited, and MEPs have to compete with each other for speaking time in plenary debates.

CONCLUSION

Politicians’ participation in legislative activities is a prerequisite for political influence. Voters whose elected representatives fail to be present in the legislature are not represented in a meaningful way. However, for the elected politicians, participation in legislative activities has to compete with extra-parliamentary activities that might enhance a politician’s personal profile among his or her electorate. Hence, it is important to examine the conditions under which politicians have incentives to prioritize legislative work. To understand what motivates legislators in multilevel systems, we have argued that not only do career ambitions shape legislative behavior, but electoral systems also influence how legislators respond to these incentives.

To examine this argument empirically, we have used the EP setting, in which politicians are elected under different electoral systems in each EU member state. Using unique data on both the stated career ambitions (from surveys) and the realized career ambitions (from post-parliament careers) of the MEPs, we demonstrate that politicians with ‘progressive’ career ambitions, who use the EP as a stepping stone to a national career, are less active in the legislature than those with ‘static’ ambitions, who wish to continue their political career at the European level.

Moreover, we find that even representatives who seek to continue their careers at the European level have lower levels of participation if they were elected in candidate-centered electoral systems than in party-centered systems. This, we argue, is because politicians in candidate-centered systems need to be visible to voters to be able to win the within-party competition for electoral support. In contrast, politicians elected in party-centered systems simply need to please the ‘selectorate’ in the party leadership. That task can more easily be achieved by focusing on legislative activities. We also find that the effect of electoral institutions in legislative participation is greater for politicians who seek to return to national politics: candidate-centered rules lead to lower legislative participation than party-centered rules.

These findings have potentially important implications for representation in the EU and beyond. Although we can assume that most voters would like their elected representatives to participate in the legislative activities of the institution in which they serve, our results suggest that party-centered electoral systems are more likely to encourage politicians to invest significant time and effort in legislative activities. In contrast, in candidate-centered systems, even politicians who want to pursue a long-term career within their current legislature have few incentives to engage in legislative activities, since their re-election depends on their links with local constituents. Such electoral systems reward politicians who raise their profiles among local voters and party members.Footnote 49 In the EU context, participation in EP committees and plenary sessions is barely noticed beyond Brussels. While the EP is dependent on members who are prepared to commit themselves to the legislative activities in order to strengthen the Parliament’s hand in its dealings with other EU institutions, it seems that the incentives to do so are largely confined to politicians who wish to stay in the EP and who are elected in party-centered systems.

These findings are also likely to be relevant to other legislatures. The EU may be unique in that the hierarchy of career paths is reversed compared to many other multilevel systems, since the EP is often regarded as the less coveted ‘lower’ legislature. However, most political systems have a hierarchy of legislatures, some of which are regarded as ‘lower salience’ and where voter attention to legislative activity is limited – hence the mechanisms of electoral selection and monitoring do not work as efficiently as in more salient elections. In such legislatures, we would expect similar mechanisms of career ambition (static or progressive) to shape legislative participation, conditioned by the type of electoral system. Research on legislative behavior in countries with mixed-member electoral systems suggests that whether a politician is elected in a (candidate-centered) single-member district or via a (party-centered) party list influences how he or she behaves in the legislature and in his or her campaigning activities.Footnote 50 This indicates that the conditioning effect of electoral systems is likely to apply beyond the specific European context.

Our results consequently suggest a trade-off between two desirable outcomes in representative democracy: (1) better-known (or more accountable) politicians and (2) more dedicated and professional legislators. This trade-off is likely to be particularly acute in low-salience legislatures, like the EP or state-level or local assemblies, where legislative participation may not enhance the public profile or re-election chances of individual legislators in their home constituencies. One limitation of this study is therefore that such a compromise may not necessarily be as evident in high-salience legislatures. Future research should examine whether this trade-off is a general phenomenon or whether highly salient legislatures encourage politicians from both candidate-centered and party-centered systems to participate in equal numbers regardless of their career ambitions.

More broadly, our findings therefore present a dilemma for constitutional designers in the EU and elsewhere. Existing research suggests that candidate-centered electoral systems provide incentives for politicians to invest time in campaigning.Footnote 51 In the EU context, these incentives lead to greater awareness about the EP and closer connections between citizens and MEPs in member states where candidate-centered systems are used, such as in Ireland, Finland and Denmark.Footnote 52 However, as our study has found, MEPs elected in candidate-centered systems are less motivated to participate and engage in day-to-day legislative activities within the EP, even if they aim to be re-elected to that institution.