Introduction

Various studies have focused on the characteristics of professional musicians’ practice methods, such as deliberate or structural practice strategies used to develop their expertise (Ericsson et al., Reference ERICSSON, KRAMPE and TESCH-RÖMER1993; Hallam, Reference HALLAM2001, Reference HALLAM, RINTA, VARVARIGOU, CREECH, PAPAGEORGI, GOMES and LANIPEKUN2012), and the amount of practice time as an indicator of high levels of musical proficiency among young musicians (Hallam, Reference HALLAM1992; Sloboda et al., Reference SLOBODA, DAVIDSON, HOWE and MOORE1996). In observing professional musicians’ performance, they have identified intuitive or analytical approaches to music practice as central to understanding how musicians accomplish music performance during practice (Hallam, Reference HALLAM1995a, Reference HALLAM1995b; Bangert et al., Reference BANGERT, FABIAN, SCHUBERT and YEADON2014). It is noteworthy that few studies have focused on the cognitive behaviours that underpin an analytical and/or intuitive approach to music performance. In addition, performers’ foci and thought processes during performance may offer important clues for determining such cognitive behaviours in relation to music performance. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to investigate performers’ cognitive behaviours, applied to music performance, by observing the specific foci in their musical repertoires and their thought processes during practice. We also attempted to identify factors that may relate to performers’ reasoning when achieving music performance.

Literature review

Bent and Drabkin (Reference BENT and DRABKIN1987), in his thorough review of music analysis, articulated that it offers a means to understand the structure and functions of musical elements. Music analysis targets a variety of forms of music including music scores, music performance and music available as a listener’s experience (p. 5). Focusing primarily on music scores, Narmour (Reference NARMOUR, Narmour and Solie1988) claimed that analysis of the contextual functions of musical components should precede performance. Berry (Reference BERRY1989) contended that music analysis is a central component of informed music making and that musicians should carefully consider the extent to which their musical decision-making is governed by their application of well-reasoned principles. Similarly, Sloboda (Reference SLOBODA1985) emphasised the use of musical knowledge in music analysis, aiming to reduce musical barriers to expert performance. These music theorists argued that music analysis provides performers with guidance on how to perform the presence of music in a score.

Although the use of music analysis of music performance has been asserted by music theorists, the nature of music analysis in performing appears to be distinct from theoretical music analysis. Rink (Reference RINK and Rink2002) suggested the concept of performer’s analysis as an independent type of music analysis. In Rink’s view, performers’ study of music scores interacts with their musical intuition – a form of musical knowledge influential in performance but non-verbally expressed (Cook, Reference COOK1994) – and results in performers’ informed intuition. Comparable with this notion, Nolan (Reference NOLAN1993) agreed that a structural analysis of music contributes to the emergence of musical sensibility in performers. Performer’s analysis, as defined by Rink (Reference RINK and Rink2002), indicates a continuum consisting of performers’ study of music driven by the structural aspects of scores and its integration with intuition in achieving music performance. Although Hallam et al. (Reference HALLAM, RINTA, VARVARIGOU, CREECH, PAPAGEORGI, GOMES and LANIPEKUN2012) focused on the development of practice strategies in relation to musical expertise, their study specifically posited an approach to music practice that analyses the structure of a music score or a piece of music before practice. It is worth noting that the concept of performer’s analysis is related to Hatten’s view of gestures (Reference HATTEN2004, Reference HATTEN2005, Reference HATTEN2010), which recognises an important link between analysis and performance. The researcher incorporated rhythm, dynamics, articulation and even physical gestures during a performance, defining gesture as ‘significant communicative energetic shaping through time’ (Hatten, Reference HATTEN2004, p. 93). Although the concept of gesture (Hatten, Reference HATTEN2012) goes beyond performer’s analysis, it opens up the possibility that all the analytic details are expressed in performing. His approach, revealing how performers feel and express even trivial musical details during performances, complements the performer’s analysis suggested by Rink (Reference RINK and Rink2002).

Acknowledging structural analysis of music score (what he calls structurally informed performance), Cook (Reference COOK and Cook1999) valued musicians’ capacity to utilise it for original interpretive ideas. Similarly, Palmer (Reference PALMER1997) defined interpretation as referring to performers’ individualistic modelling of music repertoire. Rink’s performer’s analysis (Reference RINK and Rink2002) represents a robust approach to musical interpretation, and a number of studies have shed light on how performer’s analysis works in the process of music performance. For instance, observational studies on the modification of expressive components, including rhythm, metre and tempo (Gabrielsson, Reference GABRIELSSON and Gabrielsson1987; Todd, Reference TODD1992; Lester, Reference LESTER and Rink1995; Rink Reference RINK and Rink1995; Rothstein, Reference ROTHSTEIN and Rink1995), have shown the outcomes of performer’s analysis in actual performance.

Adopting Pask’s learning model (Reference PASK1976), Hallam (Reference HALLAM1995b) attempted to identify performers’ intuitive or analytical approaches to interpretation by analysing 22 performers’ reports of how they practised. In the study, performers were divided into three groups: analytical (pursuing deliberate analysis of music scores), intuitive (relying on interpretation without conscious analysis of the music) and versatile (alternating between intuitive and analytical approaches). The findings suggested that performers tend to have their own individual ways of achieving music performance.

Bangert et al. (Reference BANGERT, FABIAN, SCHUBERT and YEADON2014) specifically investigated the nature of intuitive and deliberate thoughts in relation to musical decision-making. In the study, an expert cellist was asked to verbally describe the process of musical decision-making while reviewing a recording of the musician’s performance. The retrospective protocol analysis revealed four characteristics of musical decision-making: (1) intuitive decisions based on the musician’s feelings or senses, moment by moment; (2) procedural decisions automated by previous experiences of decision-making; (3) deliberate decisions relating to conscious planning or reasoning; (4) deliberate historically informed performance (HIP) decisions based on references to historical performance. In particular, the researchers found that musicians’ deliberate decision-making was mostly employed for the manipulation of performance features such as phrasing, articulation and tempo.

These studies sought to reveal ways of achieving music performance through intuitive or/and analytical approaches (Hallam, Reference HALLAM1995b) and types of musical decision-making used in performance (Bangert et al., Reference BANGERT, FABIAN, SCHUBERT and YEADON2014). In line with these, it is noteworthy that performers’ visualised information on music notation and reasoning processes while performing can be critical resources for revealing musicians’ cognitive behaviours in achieving music performance, possibly revealing performers’ multi-dimensional approaches to music performance.

In this study, we attempted to investigate the cognitive behaviours underpinning musicians’ approaches to performance by observing their foci in repertoires and their thought processes during practice. Following a previous research rationale (Bangert et al., Reference BANGERT, FABIAN, SCHUBERT and YEADON2014), we established a hypothesis that musicians would better recall their foci and thoughts for repertoires they had practised than for unfamiliar music. We further examined influential factors in relation to the cognitive behaviours supporting musicians’ approaches.

Methods

Participants

Totally, 52 musicians at university level (25 undergraduates and 27 graduate or postgraduate), enrolled as performance majors at a university in the United States, volunteered to participate. Two students withdrew for personal reasons before the test session. Of the 50 participants, 52% (n = 26) were female and 48 % (n = 24) were male. Their ages ranged from 20 to 35 years (M = 23.51, SD = 3.9). Their primary instruments were piano (n = 15), trombone (n = 7), violin (n = 6), clarinet (n = 5), oboe (n = 3), cello (n = 3), trumpet (n = 2), horn (n = 2), organ (n = 2), bassoon (n = 2), saxophone (n = 1), marimba (n = 1) and viola (n = 1). The time spent learning their primary instruments ranged from 4 to 25 years (M = 14.18, SD = 4.90).

Instruments

The participants were asked to bring to the test session a piece of music from their repertoires that they had been working on for at least 30 days. This restriction was deliberately established to avoid the possibility that participants might bring an unfamiliar piece of music that would require initial practice. This resulted in a sample of 50 music repertoires.

We recorded the participants’ verbal descriptions of their own familiar repertoires using a Sony FDR-AX40 camcorder fixed to a stationary tripod. The video recordings from the camcorder were transferred to a laptop computer and transcribed in a spreadsheet program.

Procedure

We set up individual meetings according to participants’ schedules. For the test session, the researchers pointed a video camera towards a music stand and the participants sat in a chair facing the music stand, upon which their repertoire score was placed. The participants all signed a consent form, agreeing to participate. We asked them to explain what they focused on in their repertoire during daily practice, pointing to the music as they explained it. Each participant was asked to provide a maximum of eight minutes of explanation, although some finished their descriptions sooner. This time period was decided after the pilot study, in which we found that the average time for participants to describe their repertoires was approximately eight minutes, regardless of the genre of the repertoire.

The participants completed a questionnaire that included age, sex, classification (e.g. undergraduate, graduate, postgraduate), primary instrument and music repertoire to be used. Participants were also given another questionnaire regarding variables that might influence their performance during practice: (1) how often do you approach your repertoire analytically? (2) how often are you required to learn about music repertoire analytically during lessons with your current teachers? (3) to what degree is an analytical approach valuable to you in achieving a performance? The participants answered these questions using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = constantly, or 1 = not at all to 5 = essential.

For the data analysis, we used retrospective verbal protocol analysis – analysis of the verbal descriptions of thought processes after the completion of a task (Kussela & Paul, Reference KUUSELA and PAUL2000) – and a content-oriented coding technique designed to focus on participants’ visualised information, knowledge and decision-making (Suwa et al., Reference SUWA, PURCELL and GERO1998). We categorised the transcribed data according to participants’ visualised information and thought processes during daily practice. Subsequently, each researcher individually coded the data, and data expressing similar main ideas were condensed into higher-level categories, referred to as operators, that indicated reasoning processes (Fonteyn, Kuipers, & Grobe, Reference FONTEYN, KUIPERS and GROBE1993). Rigorous discussion was carried out to resolve disagreements between the researchers regarding the definition of the operators.

We conducted Pearson’s correlation analysis using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) (De Vaus, Reference DE VAUS2002) to identify the influence of factors such as applied teacher’s instruction, participants’ perceived value of an analytical approach and its application to their repertoire in achieving music performance. To ensure the credibility of this research, an experienced music education researcher reviewed each step of the research and the reported findings (Lincoln & Guba, Reference LINCOLN and GUBA1985).

Findings

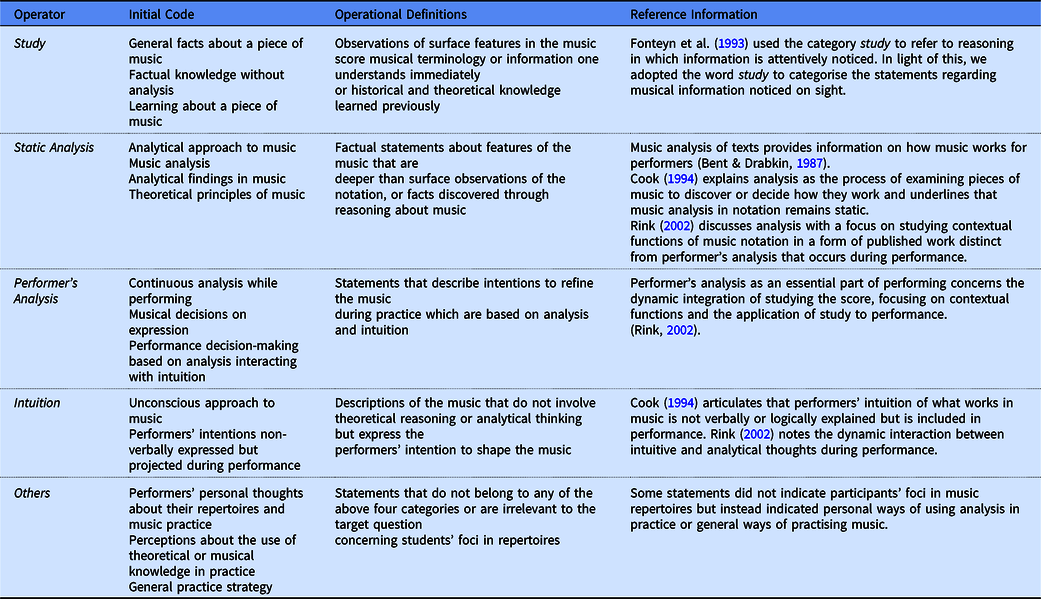

We developed five operators, four of which related to practising the current music repertoire and one of which was unrelated to the target question regarding the participants’ foci during repertoire practice. Specifically, we coded comments that referred to surface information about the repertoire as study, statements of learning about the structural aspects of music as static analysis, descriptions of the dynamic interaction between learning about music notation and performers’ decision-making as performer’s analysis, performance decision-making with no specific verbal descriptions as intuition and comments unrelated to current repertoire as others (see Table 1).

Table 1. Definitions of the Operators Utilised for Music Performance

Study

We found 137 statements indicating musical information derived from surface observation of the music score. Some of the statements reflected previous knowledge or brief research concerning the piece of music. The musical information sometimes became a basis for analytical learning of the piece of music.

P4: Mozart’s Concerto in C was written when he was in Salzburg.

P11: The title is Impromptu, but it is in a variation form.

P19: This work is J.S. Bach’s Chaconne.

Static analysis

There were 413 statements indicating participants’ analytical or theoretical understanding of musical repertories. The presence of static analysis shows that participants were involved in learning about the contextual features of the piece of music, although the degree of learning varied.

P2: Here, it is dominant and then it returns to tonic.

P13: It switches back and forth between arpeggio stuff and chromatic stuff a lot throughout the piece.

P27: I recognised the C minor arpeggio or chord outlined here, so I took that into account, noting where the thirds were, and gave them the correct intonation according to that.

Performer’s analysis

Performer’s analysis occurred continually in the dynamic between analytical and intuitive approaches to music, leading to musical shaping during performance (Rink, Reference RINK and Rink2002). We found statements describing musical reasoning and its effect on performance.

P8: I don’t go crazy with my crescendo here because I want to keep it sounding controlled.

P10: In the dominant chord, I try to bring out more emphasis or more intensity of my air.

P16: These accidentals here, I’m trying to keep them a little high to emphasise the leading.

P41: I focused on tone quality in B-minor since that’s in a new key area.

Intuition

We categorised 20 statements that did not include participants’ concrete musical knowledge or analytical ideas to their repertoire. The comments were not necessarily related to the musical shape of the performance.

P7: The characteristics of the second measure are suddenly transformed from an active mood to a stable one to a rather obscure one.

P32: It is more an internal feeling, and something is intense right here that resolves at another point.

P48: It is hard to verbally describe here, but there is something very nuanced. I tried to express this thing. I don’t think I did that consciously.

Others

Participants made 231 statements that were unrelated to performing their current repertoires including evaluative statements of the pieces, strategies or steps developed in music practice and lesson episodes with their teachers.

P11: Bach is kind of complicated, but it [this music] is really interesting.

P24: I usually look at music and listen to the recordings of other musicians, and then I play it myself.

P25: I think it is helpful to read music analytically, like simple analysis of chord progressions, because the graph works, especially for memorisation.

P50: I’ve had a lot of lessons with my professor, talking about what we could do with some musical aspects of this piece, because it’s hard to always find what to bring out musically because it is so technically based.

In summary, of the operators relating to music performance, static analysis had the highest number (n = 413, 41.8%), accounting for approximately half of the total number of statements (n = 988). Other operators followed in the sequence of performer’s analysis (n = 187, 18.9 %), study (n = 137, 13.9 %), intuition (n = 20, 2.0%) and others (n = 231, 23.38%) (see Table 2).

Table 2. Descriptive Analysis of Statements for Each Operator

Note: ‘range’ indicates the range of the number of statements provided by each participant.

Pearson’s correlation analysis was performed to reveal the relationships between the operators of music performance (see Table 3). Study was moderately correlated with static analysis (r = .405, p = .004) and with performer’s analysis (r = .363, p = .010), but no significant relationships were found between other operators.

Table 3. Correlation Between Operators Utilised in Music Performance

* p < .05. **p < .01.

The number of statements regarding static analysis was also correlated with the frequency of an applied analytical approach to music performance during individual practice (e.g. learning about the structural aspects of music, such as the contextual functions of notes) (r = .446, p = .001) and with the perceived value of such an analytical approach to music (r = .386, p = .006) (see Table 4).

Table 4. Correlation Between the Number of Statements for Each Operator and Variables, Including Applied Teachers’ Instruction, Students’ Music Practice and Students’ Perceived Value of an Analytical Approach to Music Performance

* p < .05, **p < .01.

Note: Students answered using a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5: 1 = never to 5 = constantly, or 1 = not at all to 5 = essential.

The multiple regression analysis presented in Table 5 shows that the variables explained a significant proportion of variance in the number of statements for static analysis (R 2 = .252, F (3, 49) = 5.154, p = .004 with adjusted R 2 = .203). The frequency of using an analytical approach to music performance predicted only the number of statements for static analysis, β = .409, t (48) = 2.472, p = .017.

Table 5. Multiple Regression Analysis Results for Variables Predicting the Number of Statements for Static Analysis

* p < .05

Discussion

Studies have observed musicians’ approaches to performance (Miklaszewski, Reference MIKLASZEWSKI1989; Ericsson et al., Reference ERICSSON, KRAMPE and TESCH-RÖMER1993; Hallam, Reference HALLAM1995a, Reference HALLAM1995b; Krampe & Ericsson, Reference KRAMPE and ERICSSON1996; Sloboda et al., Reference SLOBODA, DAVIDSON, HOWE and MOORE1996). In line with that research, the purpose of this study was to investigate collegiate and professional musicians’ cognitive behaviours utilised for music performance during daily practice and the influential factors relating to such cognitive behaviours. Based on the previous studies that focussed on performers’ intuitive or analytical approaches to music performance (Hallam, 1995b; Bangert et al., Reference BANGERT, FABIAN, SCHUBERT and YEADON2014), we examined performers’ cognitive behaviours relating to performing through analysis of the content of retrospective verbal protocols. The adaptation of a content-oriented analytical technique (Suwa et al., Reference SUWA, PURCELL and GERO1998) enabled us to extract four operators describing reasoning processes – study, static analysis, performer’s analysis and intuition – apart from others that indicated comments unrelated to the research question. These findings suggest that musicians’ approaches to performance are multi-dimensional, perhaps because they change their reasoning according to the characteristics of the music repertoire. Performers were found to rely on surface information regarding notation or background knowledge (i.e. study), otherwise adopting an analytical approach (i.e., static analysis, performer’s analysis) or an intuitive approach (i.e., intuition). In particular, the presence of static or performer’s analysis in the study clearly supports a need to clarify the nature of the analytical approach, going beyond music analysis as a unitary form.

The use of study was statistically related to static analysis and performer’s analysis at moderate levels (De Vaus, Reference DE VAUS2002). This makes sense given that learning about a repertoire or relying on musical knowledge provides performers with a link to other reasoning processes such as static analysis or performer’s analysis. This view of the influence of musical knowledge on performance is consistent with previous studies (Sloboda, Reference SLOBODA1985; Swanwick, Reference SWANWICK1994), though the concepts of static analysis and performer’s analysis were not clearly discussed. Interestingly, no significant relationship between static analysis and performer’s analysis was found. This may be because performers find it difficult to reflect on how their learning about the structural aspects of music repertoires is translated into performing or believe the learning itself is influential on performance in any way. Since both notions align with music analysis, a possible interaction between static analysis and performer’s analysis still warrants further examination.

Regarding the relationship between operators and influential factors, static analysis was found to be associated with the frequency of performers’ analytical approach and performers’ attitudes to the use of an analytical approach during practice, with moderate correlation levels (De Vaus, Reference DE VAUS2002). This may be a result of performers conceptualising an analytical approach to music performance as a study of the contextual aspects of music notation only, rather than performer’s analysis, and considering that concept when answering the interview questions. We did not confirm participants’ awareness of performer’s analysis in this study, but an investigation of participants’ notions of analytical approaches applied to interview questions may find an association between the use of performer’s analysis and relevant factors.

We did not include a question asking whether performers’ application of teachers’ instructions led them to perform intuitively, as teachers generally explain music pieces or performances analytically. Considering that the intuitive and analytical approaches to music performance lie on a continuum (Dunsby, Reference DUNSBY and Rink2002), it was assumed that the lack of relationships between operators regarding analytical approaches and interview answers would be linked to an intuitive approach correlating with those answers. However, such was not the case in this study. We cannot disregard the possibility that performers may not ensure about how to mention their focus on music repertoire regarding their intuitive approach that resulting in a low number of comments explicitly relating to intuition. For example, some described their analytical approach as a ‘nuanced feeling’ or an ‘instant performance decision-making’. This finding remains an issue of specific guidance on how to report anecdotal descriptions of intuition. A research design that includes students trained to verbalise their musical intuition offers the possibility of quantifying intuition, contributing to the identification of relevant variables to explain an intuitive approach.

The multiple regression analysis showed that the frequency of students using analytical approach to music performance was the only predictor of students’ comments for static analysis. This finding implies that the participants may be familiar with reporting the structural aspects of music because they are encouraged to do so. This may be understood as students’ own experience of an analytical approach leading to improvement in their music performance, which may be more influential in the establishment of static analysis than teachers’ instructions and musicians’ perceived value of an analytical approach. Further examination is necessary to observe what musical experience, or what other factors in the musical environment, lead participants to use an analytical approach to performance in order to reveal the role of such an approach in performance.

Some limitations and suggestions should be considered. We used retrospective verbal protocols that relied on memory retrieval, which is effective for eliciting comments regarding decision-making (Kuusela & Paul, Reference KUUSELA and PAUL2000). We asked the participants to point out the relevant places in the music notation but having them describe their focus or thoughts while reviewing their performance recordings may be effective in capturing performers’ descriptions of their thought processes with less faulty recall. In addition, this study did not investigate the accuracy of descriptions or musical knowledge with a goal of revealing cognitive behaviours. Such questions could be considered in further exploration since few studies have examined the potential relationship between the accuracy of musical knowledge and execution of cognitive behaviours in pursuit of a high level of performance.

Previous studies concerning how musicians perform or practise appear to be based on a dichotomous conception of the relationship between analytical and intuitive approaches (Hallam, Reference HALLAM1995a, Reference HALLAM1995b). The presence of performers’ active forms of analysis, in which analysis and intuition interact during performance (Rink, Reference RINK and Rink2002), was found in this study, suggesting that musicians’ approaches to performance need to be understood through a delicate form of categorisation consistent with the view of Bangert et al. (Reference BANGERT, FABIAN, SCHUBERT and YEADON2014).

The recognition of musicians’ cognitive behaviours may guide instrumental music teachers, so that their instruction can be established or modified according to how their students shape their performance or achieve music performance. Teachers’ knowledge of students’ foci during music performance could be a source to lead students to be more flexible in improving technical deficiencies or musicianship. Such instruction could also be effective for young performers since observation of their cognitive behaviours and experience may facilitate better performance. For young musicians, this could be a starting point for developing effective music practice strategies.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest is reported by the authors.