Singing in Spanish primary schools

Teachers colleges in Spain have provided musical instruction since 1878, and singing in schools was mentioned as early as 1884 in educational legislation. However, although music contents had nominally been included in all later educational reforms, it was only with the 1990 national curriculum that music education was made compulsory for all primary and secondary school pupils (for a historical account, see Rusinek & Sarfson, Reference RUSINEK, SARFSON, Cox and Stevens2010). This curricular stipulation was the first to be universally implemented because from 1991 all primary state schools were provided with specialised music teachers, this being obligatory in all private schools. Simultaneously a specialisation in music education began to be offered in teachers’ colleges and faculties of education as part of the 3-year programme required at that time to graduate as a ‘primary teacher’Footnote 1 which included around 500 hours of music education training and four months of supervised practicum.

In this article an analysis is offered of how specialist music teachers sing and teach singing, based on data collected from six case studies carried out in Spanish primary schools during three years. The research was motivated by practical and theoretical issues. As teacher educators, there was concern about student teachers’ attitudes towards singing, and about their vocal skills and problems. Many of them, including students from conservatoires with intermediate instrumental skills, were not used to singing. In a specific vocal training subject they reacted with reticence and occasionally with embarrassment, because they had no previous singing experience nor did they like singing. Moreover, some showed voice problems derived from poor vocal habits and a few even suffered or had been diagnosed with severe vocal disorders. This situation proved to be alarming, because these young people were prospective primary teachers who would be teaching music in the future. As professional voice users, they had to assume that their voices were going to become a work tool and that their careers might become a failure, if they did not learn how to use this delicate tool appropriately. Furthermore, if this finally were to occur, they could suffer serious personal and professional consequences, besides it being detrimental to the young people whose skills and attitudes they would be shaping.

The characteristics of children's voices and child singing have been extensively studied (Welch, Reference WELCH1985, Reference WELCH1986; Bertaux, Reference BERTAUX, Walters and Taggert1989; Phillips & Vispoel, Reference PHILLIPS and VISPOEL1990; Rutkowski, Reference RUTKOWSKI1990; Miller & Rutkowski, Reference MILLER and RUTKOWSKI2003; Levinowitz et al., Reference LEVINOWITZ, BARNES, GUERRINI, CLEMENT, D’APRIL and MOREY1998), as well as teachers’ vocal health (Escalona, Reference ESCALONA2006a , 2006b; Bovo et al., Reference ESCALONA2007; Franco & Andrus, Reference FRANCO and ANDRUS2007; Behlau & Oliveira, Reference BEHLAU and OLIVEIRA2009; Chen et al., Reference CHEN, CHIANG, CHUNG, HSIAO and HSIAO2010; Piccolotto et al., Reference PICCOLOTTO, DIAS DE OLIVEIRA, DO, PIMENTEL, DE ASSIS, DE FRAGA, EGERLAND and FIGUEIRA2010) and the impact of teachers’ voice use and singing on children (Petzold, Reference PETZOLD1963; Sims et al., Reference SIMS, MOORE and KUHN1982; Small & McCachern, Reference SMALL and MCCACHERN1983; Wolf, Reference WOLF1984; Green, Reference GREEN1990; Yarbrough et al., Reference YARBROUGH, GREEN, BENSON and BOWERS1991, Reference YARBROUGH, BOWERS and BENSON1992; Price et al., Reference PRICE, YARBROUGH, JONES and MOORE1994). Researchers have also studied vocal instruction in schools (Hughes, Reference HUGHES2007; Lamont et al., Reference LAMONT, DAUBNEY and SPRUCE2012), and analysed the implementation of educational programmes to foster singing in primary schools (Gould, Reference GOULD1969; Goetze et al., Reference GOETZE, COOPER and BROWN1990; Welch et al., Reference WELCH, HIMONIDES, SAUNDERS, PAPAGEORGI, VRAKA and PRETI2009; Saunders et al., Reference SAUNDERS, PAPAGEORGI, HIMONIDES, RINTA and WELCH2011) or to improve teachers’ singing skills and self-confidence (Heyning, Reference HEYNING2011).

In Spain, however, we found that besides our direct knowledge as practicum supervisors, and data from surveys of our student teachers’ past school musical experiences (Rusinek, Reference RUSINEK, Moore and Leung2006), there was not enough empirical research documenting how the curricular prescriptions in relation to singing had been translated into real classroom practices since the universalisation of music in the national curriculum (Cuadrado, Reference CUADRADO2013a ). Spanish generalist teachers’ vocal health has been of interest to speech therapists and pathologists as well as medical researchers in different cities and regions (Puyuelo & Llinás, Reference CUADRADO1992; Fiuza, Reference FIUZA1996; García, Reference GARCÍA1997; Aguinaga, Reference AGUINAGA1998; Preciado et al., Reference PRECIADO, PÉREZ, CALZADA and PRECIADO2005; Gañet et al., Reference GAÑET, SERRANO and GALLEGO2007; Centeno, Reference CENTENO2010), and programmes developed to help teachers improve their vocal health have also been documented (Gassull et al., Reference GASSULL, GODALL and MARTORELL2000; Casals et al., Reference CASALS, VILAR and AYATS2011). However, there is a scarcity of studies specifically focusing on how teachers sing and teach how to sing: for example, Cámara (Reference CÁMARA2003, Reference CÁMARA2004, Reference CÁMARA2005, Reference CÁMARA2008) focused on the relation between pupils’ decreasing interest in singing activities at different educational levels with the dichotomy between in school and out of school music activities, and Elgström (Reference ELGSTRÖM2001, Reference ELGSTRÖM2002), from the perspective of teacher training, studied the singing voice models of Spanish music student teachers and the ways they were adapted to primary pupils’ vocal range (Elgström, Reference ELGSTRÖM2007).

The present article therefore aims to bridge the gap between scarcity of research about the teaching of singing in primary schools and the practice of music teacher education, through an empirically grounded study.

Methodology and research design

The research was carried out using qualitative methods. Case study was the chosen strategy of inquiry because of its holistic, empathic and interpretive nature. The approach was instrumental (Stake, Reference STAKE1995), that is, a varied and balanced sample of cases was selected to answer the specific question of how music teachers were teaching singing in primary schools. After the first two case studies had been completed, new cases were chosen responding to the need to obtain new data to verify or contrast the emerging categories, following the principles of theoretical purpose and relevance and of theoretical saturation proposed by Glaser and Strauss (Reference GLASER and STRAUSS1967), to decide what and how many cases were needed. Thus, a maximum variation sample resulted (Lincoln & Guba, Reference LINCOLN and GUBA1985), which took into account teacher age, gender, training and vocal profile, along with the type and location of the schools they worked in. Attending an in-service vocal training course for music teachers was crucial to having practical access to a wide range of possible informants, making a multiple case study analysis possible (Stake, Reference STAKE2005).

Fieldwork took place during three school years, in six state and private schools in the city of Madrid and its surroundings. The duration of the data collection for each case study varied from two months to six months, depending on the practical needs of the case, on theoretical saturation, and on our search for corroborations of our findings. Data were collected through qualitative methods such as classroom observations, systematic field notes, individual semi-structured and open interviews with the teachers, and revision of documents such as lesson plans and school public documents. For each case, all classes from Y1 to Y6 were observed, in order to better understand how the teachers changed their strategies according to the pupils’ age, summing up 47 class observations for the whole project. The participants were interviewed at the beginning of each study to know their musical and pedagogical profiles and training, and after the classroom observations in order to understand their approaches by triangulating what we observed with what they told us about classroom singing, totalling 22 in-depth interviews. All the participants shared with us their lesson plans and annual subject plannings, and facilitated access to the school documents that referred to the arts. Permission for the observations was requested and obtained from the teachers and the school authorities, and the anonymity of all the participants and schools was granted, and kept throughout the research.

The analysis was cyclical and recurrent, informed by grounded theory techniques such as the realisation of constant comparison of categories (Glaser & Strauss, Reference GLASER and STRAUSS1967), and supported by the use of the qualitative data analysis software Atlas.ti. It started with etic categories (Harris, Reference HARRIS1976) such as the part that singing had in lessons, its relevance for teachers and pupils, whether there was vocal training or not, the strategies used to help pupils solve their vocal problems, the sequencing of vocal learning across primary and the continuity of its teaching, and the assessment of pupils’ vocal progress. As we kept collecting more data, new emic categories appeared − emerging from the participants’ discourse, such as dissatisfaction with their initial training, in-service training needs, and lack of institutional support − which helped us to understand the relation between teachers’ vocal training, their vocal models, and classroom practice. To corroborate the findings, triangulation of data collection methods, informants and observers was used (Flick, Reference FLICK1992).

The whole investigation tried to understand how Spanish primary music teachers sing, the characteristics of their classroom singing practices and of their teaching of singing, and the relation between their spoken and singing models with their understanding of the impact of these issues on children. In the next two sections data related to music teachers’ teaching of singing are analysed, illustrating the different approaches we found with short scenes taken from the classroom observations.Footnote 2 The approaches focusing on the teaching of singing are discussed first, and thereafter those which include singing songs without considering vocal instruction. In the last section we summarise our findings, including a comparison among the different approaches we found in relation to singing in the music class. Derived from the findings, the article concludes with some suggestions regarding the vocal training of prospective music teachers.

Teaching primary pupils to sing

Singing is a highly complex skill that demands multiple psychomotor coordination (Phillips, Reference PHILLIPS and Colwell1992, Reference PHILLIPS1996; Phillips & Aitchison, Reference PHILLIPS and AITCHISON1997). Vocal production depends on joint psychological processes, such as tonal perception and tonal memory, and on physiological processes, including closing and tautening the vocal folds with appropriate breath pressure. T1, a female music teacher in her early forties with 20 years of teaching experience, was conscious of this complexity. Despite her limited musical training when she had graduated, since then she had continued taking music and singing lessons. T1 transferred that learning to her teaching, incorporating sequences of specific exercises oriented to the vocal instruction of her pupils. Their complexity progressed gradually across the six primary gradesFootnote 3 to help pupils develop appropriate kinaesthesic perceptions to facilitate the coordination of vocal sound production. The articulation and diction exercises were based on the prosody of the lyrics, most of the time taken from the class repertoire. Moreover, she made a conscious effort to adapt these exercises, so that children could develop complex psychomotor processes in a playful manner.

-

– Let's stretch. It's OK to yawn. Let's try to touch the ceiling. Arch your back. Move your shoulders, first one, then the other, and now both together. Let's breathe. . . Now we put our hands on our partner's ribs. We try to feel the ribs. Not that way . . . shoulders don't go up. Let's expand when we breathe in, and then we breathe out. Let's turn round.

They break the circle and sit down:

-

– A balloon! I start! Let's inhale – she says, pointing to her diaphragm. Then she starts exhaling while she keeps pointing to her diaphragm. The children pay attention to what she is suggesting. A soft ‘s’ is heard: sssssssssss.

-

– Are you ready? Let's pretend we have a little balloon, we fill it with air and let the air out slowly, saying ‘ssssssssssssss’ with a half smile.

T1's vocal instruction was based on a precise understanding of group and individual vocal problems, for which she used specific strategies. As her own determination to learn how to sing came about from overcoming frustrating experiences as a child, she did not assume age or gender to be valid reasons not to sing in the classroom. Her targets were attained, and even if a few would be out of tune, all pupils sang in all primary years.

Besides her primary teacher diploma, T2, a female in her late fifties with around 30 years of teaching experience, held a bachelor's degree in music as a pianist, as well as a degree in education, and had taken singing lessons and participated in quality amateur choirs continuously. She taught music to Y1, Y2, Y5 and Y6, and directed an after-school choir. For Y1 and Y2 she used exercises based on the lyrics’ prosody together with melodic sequences to be imitated, and included individualised assessment to overcome the vocal difficulties of the songs.

When children quiet down, she sings an ascending octave scale from middle C, and then continues with some examples within a range of a fifth. Sometimes she demands legato and helps them with a gesture. For the staccato she helps them with an image:

-

– As if it were very hot! –she tells them, − You’re doing it very well, except somebody buzzing over there. Softly . . . −she says while indicating that each pupil sing individually. – Well done!

In contrast with Y1 and Y2, we observed that most students in Y5 and Y6 did not seem motivated to sing, or did so out of tune, producing strange heterophonies – a few, practically reciting. Y3 and Y4 were taught by another music teacher,Footnote 4 and according to T2, when she met pupils again after two years she found that they had lost their ability to sing, except for those who had continued to sing in the choir. The paradox was that although she used specific vocal training exercises and paid attention to breathing, emission, tuning, articulation and diction to conduct the school choir with children of similar ages, in the regular classes she did not. Although in the interviews T2 expressed her concern about the Y5 and Y6 vocal problems, in the end she gave up including specific strategies to resolve them.

T3, a male music teacher in his late fifties, with 30 years of teaching experience, had no formal music training. However, he was committed to innovation within the progressive state school he worked in, and was continuously attending diverse in-service training courses and getting involved in projects, like for example, a Spanish version of Write an opera. His educational commitment had moved him to include certain aspects of vocal training in his teaching, such as paying attention to posture or being conscious of the diaphragm, but out of his own lack of systematic learning to sing, he did not consider other essential aspects of voice production. He assessed pupils' posture and breathing, but his verbal or visual references were meaningless, because they did not stem from a real singing experience. Pupils could not understand the images he used, which were ultimately of no use in developing their singing skills.

The song starts after a percussion introduction. Both pupils and the teacher's higher tones sound harsh, slightly flat, and forced.

-

– This should be sung standing up! Let's keep up the rhythm and listen to ourselves. Liberate your voices!

They repeat the beginning with the same results.

-

– We must liberate our voices. We are helping them to go high!

T3 proposes an exercise consisting in singing the word ‘goal’ with an octave interval, to be sung one by one. It is impossible for the first three pupils and they sing something different. A boy, with a broken voice, sings it more in tune. The teacher tries to exemplify the exercise, but his voice breaks. The pupils laugh, and he explains he is a bass. A girl finds it very difficult. The following pupils, a boy and a girl, simply change the interval.

We observed that the teacher's vocal model was characterised by a harsh emission and lack of projection. Pupils’ voices presented an open, hard and hoarse sound because they were forcing their throats. T3 did not seem to have a clear understanding of their vocal problems, which were similarly significant in all primary years, and most of the times, he was asking them to perform procedures he had not assimilated himself. Thus, pupils ended up reproducing a jargon of visual and verbal references that corresponded with wrong kinaesthetic perceptions, and which did not help them to improve their singing. Apart from a deficient voice emission when speaking and singing, they showed difficulties when singing high tones, imitating melodies or finding a tonal centre, which in the end often resulted in singing out of tune.

Singing songs without vocal instruction

Vocal production is basically similar in children and adults, and requires complex psychomotor coordination. However, although there is medical and educational consensus in the scientific literature about the idea that children can and must learn to sing, with a progressive approach to control vocal muscles (Staloff & Spiegel, Reference STALOFF and SPIEGEL1989), some teachers, like T4, T5 and T6, seemed to expect these coordination to happen spontaneously. While this occurs with a few children, the problem is that many others present circumstances that hinder the coordination.

T4, a male music teacher in his early thirties with less than 10 years of work experience, taught in a religious school, the only private one in our sample and the only one without a music classroom. He had been continuously singing in choirs since he was 17. Although when T4 graduated as a teacher his musical training was limited, he had taken some singing classes, and had attended many choral conducting courses. His teaching approach consisted of carrying out the activities proposed in textbooks, limiting class repertoire to the songs included in them and using recordings instead of singing himself. Sometimes, provided the characteristics of the recorded accompaniments, the acoustic pollution in the classroom increased so much that it was difficult to hear and feedback between pupils and teacher was hindered. T4's vocal model was appropriate for pupils’ needs, but as the noise impeded a clear perception of their performance, he was not able to help them produce a good vocal sound.

-

– Open page 70. I’m going to play this song and then I’ll ask you to sing it!

In the recording, a child's voice is heard that asks a question and an adult female that answers. The questions refer to legs, mouth, wings, etc., and the answers to walking, singing, flying, and so on. The recorded accompaniment does not let pupils’ voices be adequately heard. The volume is too high. The teacher and the pupils sing with the recording. Then, T4 asks for volunteers to be individually assessed. The first volunteer hardly sings. The second recites – he practically prays. T4 corrects him. The third child sings it more or less, but the fourth changes key.

T4 perceived that some children sang the wrong melodies and that some others recited, but did not use any strategies to help them improve their singing skills. What surprised us when we observed him conducting the school choir was that he did use specific strategies with children of the same age in that out-of-class context.Footnote 5

T5, a male music teacher in his early fifties with 15 years of teaching experience, had taken singing lessons during three years to compensate his initially limited musical training. He did not have a wide musical experience, but he used to write songs and had worked as a dubbing actor. For teaching he followed a textbook with a complicated repertoire, including songs of wide melodic extension, difficult intervals, long lyrics, and arrangements that were not very adequate for primary. T5's class discourse was contaminated with certain images normally found in the teaching of singing. Teaching how to sing presents challenges due to the nature of the voice as an instrument whose mechanics are internal, intangible and difficult to show. That is why it is never free of subjectivity, as Phillips (Reference PHILLIPS and Colwell1992) suggests, despite the accumulated scientific knowledge about singing, and also why the language predominant in the teaching of singing is ambiguous (Welch et al., Reference WELCH2005). The misleading, often incorrect images without practical examples used by T5 were far from real vocal physiology, and confused pupils. Furthermore, their imitation of his vocal model, with timbre alterations such as broken voice, sometimes promoted phonotraumatic behaviours.

-

– In this song I will grade you for singing. Put your souls into it!

Pupils remain seated and start singing all together. Most sing in a lower octave, below middle C, and some purrs are heard.

-

– Maintain a constant air flow until the end! Pay attention and sing alone now! If you make a mistake, make it graciously! Raise the volume in ‘a’!,

-

– he keeps indicating. – Good job! It's easy, isn't it?

Now they stand up, and boys and girls alternate in pairs for the verses.

-

– Sing for me!

Boy 1 and girl 1 sing in their octave, but boy 2 and girl 2 purr. In the following verse boy 1 loses the tone and finally prays the lyrics. In the third verse boy 1 sings another melody, and so does boy 2 in the fourth. Girls 1 and 2 also end up praying.

-

– Bring your voices out! You have to go up!

T5's pupils presented a variety of vocal problems similar to T4's pupils, but they sang in the wrong octave. Singing in a lower register produces a rough sound that might damage vocal folds (Phillips, Reference PHILLIPS1996) and is one of the reasons why some children sing out of tune. Although his pupils occasionally sang in the right octave and in tune, most of the times they did not. T5 was only partially aware of their problems, and therefore he could not offer any appropriate strategies to remedy them.

T6, a female music teacher in her early thirties and with only two years teaching experience, only sang sporadically in primary due to vocal disorders. Since she did sing systematically in nursery, we asked her to observe her vocal practice there. She sang in a very low register, and as the lesson went on and her vocal fatigue increased, she only sang the beginning of the phrases, remaining silent while pupils sang. Her unhealthy vocal model (vocal folds nodules had been diagnosed) and her use of inappropriate terminology also induced pupils to produce an unhealthy voice.

Pupils start singing ‘Saco la manita’, accompanied with gestures. It's very low. They continue with ‘A mis manos yo las muevo’. Besides being low, the sound is rough. T6 changes key in the middle of the song, but lowering it even more:

-

– You must sing louder, I can't hear you!

Children's responses were varied: some sang in the proposed range, some looked uncomfortable while trying to find a better key to sing in, others recited in a kind of purr or parlato. The observed situation contradicted generalised recommendations about teaching singing regarding the use of a melodic range adequate to the characteristics and development of children's voices and about avoiding very loud or very weak intensities (Philips, Reference PHILLIPS1996). As T6 was not conscious of the impact of her vocal model, she used no strategies to help children with their singing skills. Moreover, she did not take into account that by insisting on the wrong kinaesthetic associations, they would eventually develop bad singing habits that, once established, could continue for life, as Phillips (Reference PHILLIPS1996, p. 72) warns. This approach was inappropriate for learning to sing, and even harmful for the children's vocal health.

Findings

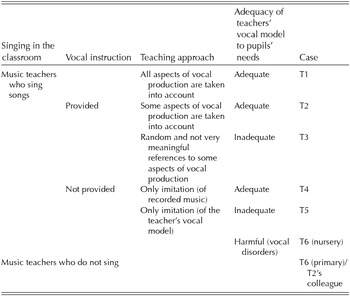

While it seems logical to expect that all primary music teachers sing in their classrooms, according to the data collected it was actually found that there were music teachers who did not sing. The differences among the approaches toward singing between those who did sing, referred to: (1) the provision of vocal instruction besides singing songs; (2) the teaching approach and children's learning schemes when there was no vocal instruction; and (3) teachers’ vocal models. The resulting teaching styles are summarised in Table 1:

Table 1 Teaching styles

Vocal instruction, as Phillips (Reference PHILLIPS1996, p. 3) contends, ‘is appropriate and necessary for all students’ because in order to be able to learn a wide and varied repertoire, they need to acquire singing habits in accordance with vocal needs. This was documented in Phillips and Aitchison's (Reference PHILLIPS and AITCHISON1997) empirical study, where they found that ‘students’ singing skills in general music can be improved through vocal instruction that moves beyond the song approach’ (p. 195). If we agree that singing skills can be developed and that they are not exclusive of the most gifted (Russell, Reference RUSSELL1997), it seems reasonable that boys and girls receive some kind of vocal instruction within their compulsory education which enables them to use their voices adequately. This is what was observed in the classes of T1, T2 and T3. T1 paid specific attention to all physiological and psychological processes, and the teaching of singing was a prevailing activity in her classes, besides the use of songs as a resource to articulate musical and extramusical learnings. Vocal instruction was progressively sequenced with specific exercises for relaxation, adequate posture, breathing, a fatigue-less emission, and correct articulation and diction, and was provided with continuity and recurrency. Her intensive vocal instruction style aimed at developing the necessary vocal skills, stemmed from her reflexion as a teacher, who was conscious of herself as an adolescent who had not sung due to a negative childhood experience, and her determination as a practitioner who knew how to make use of the delicate human voice. T2 also paid attention to vocal instruction with Y1 and Y2, but she did not take into account all the necessary aspects in developing singing skills, such as body posture. The teaching of singing is usually based on the teacher's experiences as a student and as a performer, and on his or her personal reflection. T2 had grown up singing since childhood, and was still singing as an alto in quality amateur choirs. Her contradictions, not supporting Y5 and Y6 pupils in the regular music class, derived from the fact that her approach was a by-product of her singing experience, more than due to professional reflection.

T3 was concerned about vocal instruction besides singing songs too. However, he provided it in an asystematic, random and, basically, non-meaningful manner. He paid attention to posture or becoming conscious of the diaphragm, but not to other processes that are indispensable for coordinating vocal production. Moreover, references to those processes were merely verbal or visual, because they were not deeply understood. In teaching singing, Welch et al. (Reference WELCH, Miell, MacDonald and Hargreaves2005) observe, there is a predominance of a confusing oral culture that most of the times does not coincide with what has been documented by scientific research. Nevertheless, the use of an ambiguous metaphorical language is accepted for its contribution to developing ‘pallesthésique’ and kinaesthetic memories, for perception and muscular movement respectively (Mauduit, Reference MAUDUIT2005, p. 12). Although T3 used singing intensively, both for musical and extramusical learning, and for classroom management, his lack of meaningful understanding of vocal instruction invalidated his efforts.

One of the most important challenges for a music educator, as Phillips (Reference PHILLIPS1996) argues, is to get children involved in singing. The problem arises when song teaching is emphasised, but the voice is neglected, and this is what we observed in T4 and T5's classes. Although an appropriate vocal model for children's needs was used, T4's teaching ended up denatured, because he uncritically used textbook repertoires and their suggested activities, including recorded accompaniments. Teaching singing requires a continuous feedback, where teachers assess pupils’ vocal performance and correct it by singing back with an appropriate voice quality and tuning; thereafter pupils sing again with an improved vocal performance. The high volume of the recorded accompaniments and the noise in the regular classrooms where T4 taught music, did not allow for that feedback. Teaching to read music before developing vocal skills is ‘like the proverbial cart before the horse,’ as Phillips (Reference PHILLIPS1996, p. 12) also warns. This is what T5 did when he used singing mostly as a resource for learning music notation, because pupils were actually deprived of the opportunity to develop their vocal skills.

The coordination of the physiological systems which generate sound for speech and singing with the neural processes which control these systems, are primarily developed by imitating (Gruhn, Reference GRUHN, Haas and Brandes2009). The imitation of a model (Bandura, Reference BANDURA1971) is one of the main means of human learning, and this is also the case with speech and singing, where vocal modelling plays a crucial role. Human beings are consummate vocal imitators (Brown, Reference BROWN2007), whose skills are developed in informal contexts within enculturation and breeding interaction (Welch, Reference WELCH, Miell, MacDonald and Hargreaves2005). Both in those informal contexts, and in formal school contexts, vocal modelling affects tonal perception and, therefore, tuning and voice quality, due to the relation between sound perception and production (Phillips, Reference PHILLIPS1996). The teacher's vocal model for speaking and singing is crucial in children's vocal learning. That is why we were concerned about the participants’ vocal models, and about the relationship among the vocal models, teacher approaches towards vocal instruction, and pupil response. We found that T3, T5 and T6 presented vocal models that were inadequate for pupils’ needs; T1, T2 and T4 presented adequate vocal models; and only T1 was conscious of its impact on pupil learning. T4's use of recorded songs instead of singing himself, also showed us that an adequate vocal model is a necessary, but not sufficient, condition for helping pupils to properly develop their singing skills.

Our observations of T6's classes in primary and of T2's colleague unfortunately documented the possibility of music teaching without singing, something we had not only heard about but also knew of due to our roles as practicum supervisors. T6 was not sensible to the consequences of excluding singing from teaching in primary, and tried to justify this exclusion alluding to pupil reluctance and problematic backgrounds. However, as we found by observing her when teaching younger children, the absence of singing in primary derived from her bad singing habits and severe vocal disorders.

In conclusion, these case studies show the relationship among music teacher vocal training, their vocal models, and their different approaches towards the teaching of singing and the assessment of pupil vocal problems. These findings corroborate the need for thorough pre-service vocal training to face the challenges of the teaching profession. Music teachers need vocal training in order to take care of their own vocal health as professional voice users exposed to risk factors such as its overuse, and furthermore, to take care of their pupils’ vocal health by providing adequate spoken and singing vocal models, besides being able to teach them to sing. We also found that the participants did not have a coherent theoretical framework to teach singing, even those who had competent singing practice. The findings confirm Phillips’ (Reference PHILLIPS1996) argument that if teachers are not familiar with childrens’ and adolescents’ vocal production issues and do not understand what can be expected from voices in those age groups, they can hardly help their pupils to develop their singing skills. The findings also suggest the convenience of rethinking the usual approaches in music teacher education, so that besides appropriate vocal training, they also make them conscious of the impact of their own vocal models and help them to develop a coherent theoretical framework for understanding the nature and particular needs of their future pupils’ voices.