Introduction

In the UK, there are 44 choir schools attached to cathedrals, churches and collegiate chapels to educate choristers. Roughly, 1200 boys and girls are choristers out of the 20,000 pupils in choir schools.Footnote 1 Thirty-nine choir schools are fee-paying independent schools and five others are state schools. A further eight cathedral foundations draw their choristers from local schools. In this study, all participants were full-time choristers who had sung at least three services every week and were educated in one of the UK choir schools. Here, ‘choristers’ refers to young people (boys aged 8 to 13 years and girls aged 8 to 18 years) who sing the treble line in UK cathedrals, minsters and collegiate chapels. The majority of choir schools are Church of England foundations, but a few belong to Roman Catholic, Scottish and Welsh churches. In reality, there is no requirement for choristers to have had any experience of worship; they just need to be comfortable with the ethos of the church setting.

Challenges of chorister recruitment

Over the last couple of decades, the numbers of parents wanting their son or daughter to be educated in a choir school have been declining. The reasons for this are threefold: 1) a reduction in the number of church goers; 2) a steady rise in the cost of such schooling and 3) boarding their child at such a young age has become less attractive to parents. These are discussed below.

Firstly, although the Church of England is the main Christian denomination in England and Wales, it has suffered a dramatic loss of its followers. Statistics on UK Church membership show it has ‘declined from 10.6 million in 1930 to 5.5 million in 2010, or, as a percentage of the population, from about 30% to 11.2%’ (Faith Survey, 2021Footnote 2 ). In England, Church membership is ‘forecast to decline to 2.53 million (4.3% of the population) by 2025’ (ibid). The British Social Attitudes Survey (1983–2018) indicated that the number of people with no religious affiliation has nearly doubled from 12.8 million to 24.7 million.Footnote 3

Secondly, there are children who are musically talented, with supportive parents who also value this kind of education but cannot possibly afford yearly fee increases without financial assistance. The bursary system (choral endowment fund) plays an important role to keep choristers in those established choral foundations. For example, in 2019, Liverpool Metropolitan Cathedral received £20,000 for instrumental lessons for girl choristers, and at Durham Cathedral £25,000 in bursary funds was shared among boy and girl choristers. Various organisations such as FCM (Friends of Cathedral Music) also give substantial financial support to this long-running choral tradition.Footnote 4 For instance, the FCM Diamond Fund for Choristers was launched in 2016 at a concert in St Paul’s Cathedral. It aimed to raise funds for supporting choristers and cathedral music departments in need and has since provided £140,000 worth of grants to 24 choral foundations. The Diamond Fund aims to raise £10 million by 2020 to relieve hardship with specific grants in order to fund cathedral choristerships. Footnote 5

Unfortunately, this task was made more difficult by the recent global pandemic. In April 2020, hundreds of headteachers at fee-paying schools across the UK sent pupils home and got staff to switch to online teaching in response to the national lockdown by getting 25% per cent discount on the coming term’s feesFootnote 6 (Financial Times April 7th 2020). Two months later, The Sunday Telegraph reported that 30 British private schools were preparing to close due to the coronavirus pandemic, with parents struggling to pay fees contributing to their collapse. For example, York Minster announced it was closing the Minster School before September 2020. Durham Cathedral has decided to merge The Chorister School (where choristers are educated and boarded) with a nearby independent school, Durham School, by September 2021.

Thirdly, boarding is still compulsory for young choristers in 10 choir schools around the country. The better-known examples are St. Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey Choir Schools (London) and King’s College School (Cambridge). In 2019, the headmaster of Westminster Cathedral Choir School ended full boarding, explaining that it was a barrier to recruiting choristers. On the other hand, 29 other independent choir schools do not require young children to be boarders, which means choristers can go home after their singing duties or arrive earlier in the morning for rehearsals. Boarding is becoming less attractive nowadays. The sudden lack of emotional contact with parents seems to be having a negative impact on family relationships (Dong, Reference DONG2018).

Chorister outreach programme and funding opportunities

Due to the growing shortage of applicants in some parts of the country, the church foundations keep trying their best to find other ways of recruiting new members, whether the youngsters are religious or not. They offer ‘Come-and-be-a-Chorister-for-a-day’ sessions as a chance to do an informal ‘pre-audition’ to see which children are musically talented and should be invited to the formal voice trials. Evidence for this can be seen in the Choir Schools Association ‘Reaching Out’ bookletFootnote 7 published in 2018. It is also an opportunity for parents to learn about choristers’ life and see if that suits their child.

From 2007 to 2014, in the hope that thousands of local primary school children from widely differing backgrounds could benefit from a good quality singing experience, £40m government funding was given for a national programme called ‘Sing Up’ (Welch et al., Reference WELCH, HIMONIDES, SAUNDERS, PAPAGEORGI, RINTA, PRETI, STEWART, LANI and HILL2011) of which the national Chorister Outreach Programme (COP) was a very effective part, receiving £1m per year from the Autumn of 2007 through to Summer of 2010. Over those 3 years, there were 4,000 school-based workshops that involved 60,000 primary-aged children. The COP initiative sent 1,000 choristers connected to religious establishments to sing with children in local primary schools and became their role models. The report shows COP had a positive impact on children’s singing development with participants demonstrating advanced skills compared with children without such experience. Participants were developmentally approximately 3 years ahead of children without such experience (Saunders et al., Reference SAUNDERS, PAPAGEORGI, HIMONIDES, VRAKA, RINTA and WELCH2012). It was further shown that singing is not elitist but open to all.

Studies related to choristers’ education

Previous studies have demonstrated how English cathedral choristers’ lives are strongly linked to ritual practice (Mould, Reference MOULD2007), and that the amount of time choristers spent in practice is one of the key factors in attaining high achievement in choral singing (Barrett, Reference BARRETT and Barrett2011). Much of the existing research has been conducted through analysing choristers’ voice development (e.g., Williams et al., Reference WILLIAMS, WELCH and HOWARD2005), observing choristers’ demanding life in choir school settings (e.g., Barrett & Mills, Reference BARRETT and MILLS2009), explaining choristers’ voice change through puberty (e.g., Ashley, Reference ASHLEY2013), comparing the differences between boy and girl choristers’ singing voices according to audiences’ perceptions (e.g., Howard, Barlow, Szymanski & Welch, Reference HOWARD, BARLOW, SZYMANSKI and WELCH2001; Howard, Szymanski & Welch, Reference HOWARD, SZYMANSKI and WELCH2002) and discussing the possibility of training girls to sing just like the boys (Sergeant & Welch,Reference SERGEANT and WELCH1997). Day’s research (Reference DAY2014) also illustrates the distinctive ‘whiteness’ singing style of English choristers and the reason for such exercises concluding that the overall English style is characterised by the absence of vibrato compared with the extra control, restraint and reserve of the German style.

Furthermore, some studies have been published to deepen our understanding of English choristers’ training. Researchers have been exploring how music learning and development occurs in this unique setting in the 21st century, and what individual, social and/or cultural conditions seem to support the development of young choristers’ expert performance. The evidence from Barrett (Reference BARRETT and Barrett2011) suggests that family environmental factors such as ‘early exposure to/instruction in music’ and ‘strong family support’ are keys to the development of a chorister’s musical expertise. Barrett also noticed that youngsters were selected through auditions that not only tested a child’s musical potential but also looked for the social skills and capacity required for ‘self-sufficiency’. These environmental conditions combine with individual drive, focus, peer mentoring and structured practice essential for a productive learning experience. Other studies focus on purely vocal training within the English cathedral choir setting. For instance, Williams found the average age at which the voice started to change to be 12+ years (Williams, Reference WILLIAMS2007). She later conducted a detailed study (Williams, Reference WILLIAMS2010) on the connections between school environment, vocal activity and the vocal health of choristers, to investigate the impact of the intense schedule (rehearsal and performing) on the boys’ vocal health and future development. Significant differences were found between the vocal health of boys who were boarders in that choir school and sang intensively and those who did not sing. Although boarding choristers had the highest vocal loading, they had the lowest incidence of voice disorder, suggesting that choristers learned how to use advanced vocal techniques to reduce the levels of vocal damage. Howard et al., Reference HOWARD, WELCH, HIMONIDES and OWENS2019) explored three teenage girl choristers’ voice development during puberty and reported that a very significant degree of vocal control was established within a close-knit choral context. The girls were trained to listen to each other and modify their own sung pitch and timbre in order to blend in well and contribute to the overall choral sound. An improvement was also evidenced in word pronunciation and vocal projection.

The above studies are valuable but none of them explains what more might be achieved musically within the choristers’ already very demanding schedule. The aim of the current study is to explore how being a chorister, and having this unique experience with its extremely busy schedule, influences the development of choristers’ music skills, and asks the following questions:

-

1) What kind of musical skills can choristers achieve through this intensive regime?

-

2) Do choristers develop a lifelong interest in music?

Methodology

This study investigated ex-choristers’ perceptions by using in-depth semi-structured interviews. Thirty participants in the study (24 male and 6 female) were all ex-choristers who attended 11 English choir schools between 1940 and 2010. They were divided into three groups according to their status during this project: those in secondary or tertiary education; those in work; and retired people. All had been expected to sing at least three services in cathedrals or college chapters every week and received an intensive music education whether they were boarders or not.

Snowball sampling, also known as ‘chain-referral methods’ (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, Reference COHEN, MANION and MORRISON2011) was used in this study based on personal recommendation, which means the interviewees would recommend a potential fellow chorister to be interviewed. In snowball sampling, interpersonal relations feature very highly. This approach helped identify individuals with the characteristics this study focused on and used social networks, informants and contacts to seek out further individuals. The Federation of Cathedral Old Choristers’ Associations and Choir School Association were also contacted at the pilot study stage and they kindly recommended several ex-choristers from around the country.

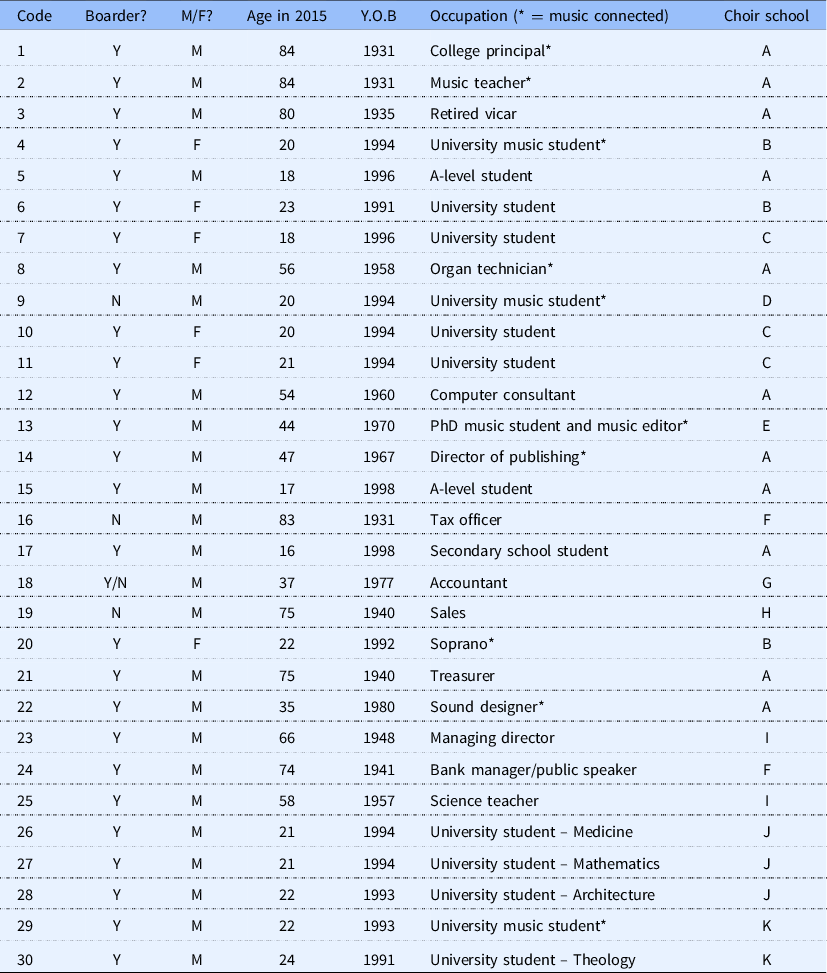

The data were collected through semi-structured interviews at various locations with six of the interviews conducted online. Most of the interviews were face to face, in a café or at the interviewee’s house, which provided a comfortable environment for the respondents to reflect on and share their childhood experience as a cathedral chorister. The final sample included 15 interviewees aged 30 years or under, and 15 over 30 years. Of those 30, 6 were female, all in the under-30 age group. The majority were boarders, with only four having attended non-boarding choir schools. Most interviewees still have an active interest in music, and 10 had or still have an occupation connected to music. More sample details can be seen in Table 1.

Table 1. Sample details

Ethical procedures were followed in line with the expectations of the British Educational Research Association, and ethical approval was granted by Durham University ethics committee. Before each interview, it was made clear to the participants how the interview would proceed, that it would be recorded, how the data acquired would be subsequently used, and that in every case anonymity would be fully preserved at all times. After each interview, the participants were asked to fill in and sign a consent form. The participants were further informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time, even after the interview, and without having to give a reason for withdrawing. All interviewees were allotted a four-digit number as their private code in the final report in order to make all participants anonymous. The first two digits referred to the order of interview; the third digit showed whether the interviewee was male or female (1: male/2: female); and the last digit meant boarder or non-boarder (1: boarder/2: non-boarder). (For example, 4512 would have meant that interviewee No. 45 was a male non-boarder). This meant they could not be identified or traced.

The interview data were then subjected to thematic analysis, a way of recognising patterns within the data, where emerging themes become the categories for analysis which can be divided into codes (Boyatzis, Reference BOYATZIS1998). All semi-structured interview transcripts in this study were coded several times using Nvivo software in order to organise and group the interview data thematically.

Findings

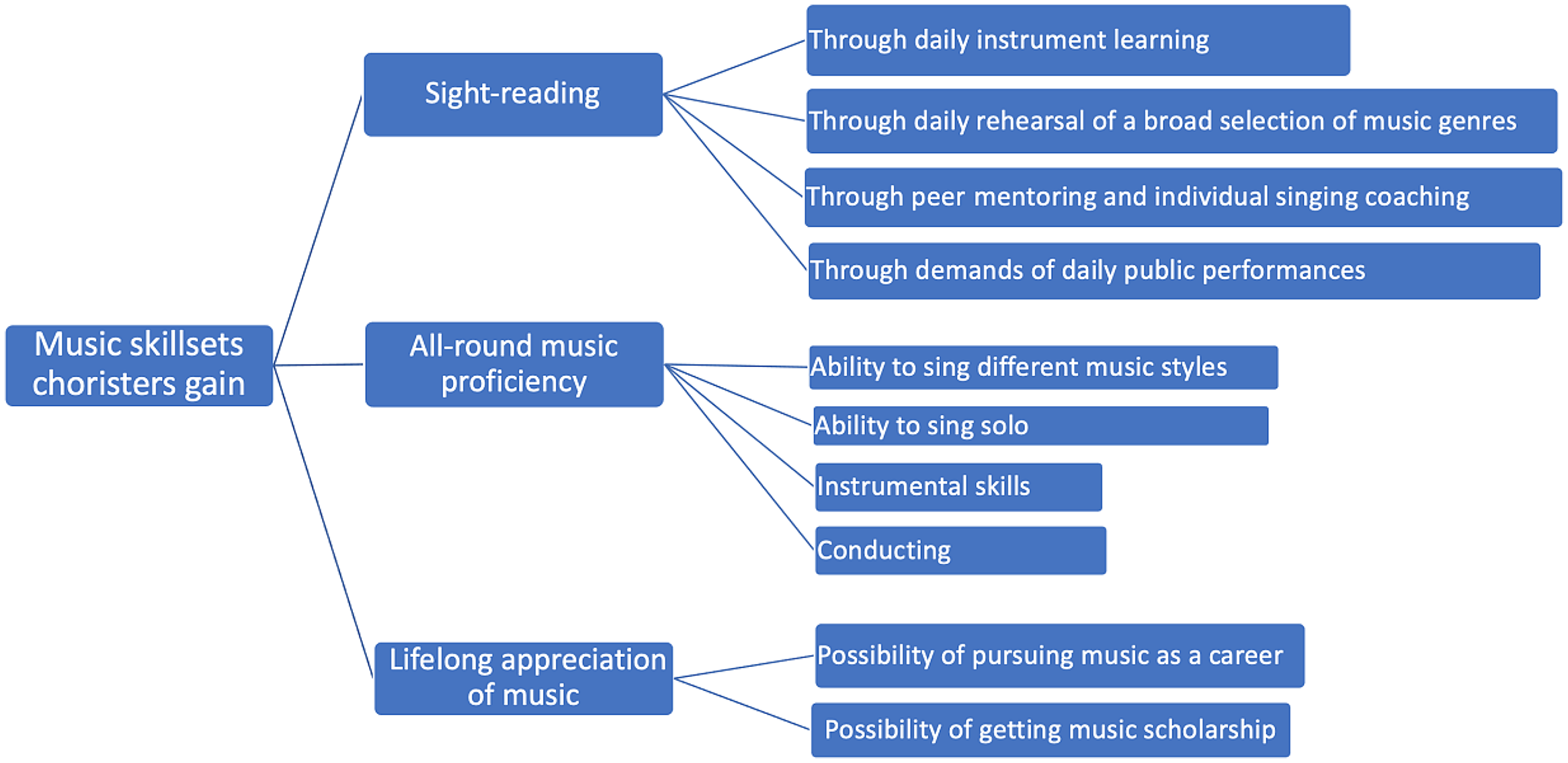

The main musical outcomes emerging from the 30 interviews conducted for this research can be divided into 3 sections. The first refers to the development of sight-reading skills that most choristers gained through their 5 years of training. The second section concerns the development of an all-round musicianship that a vast majority of choristers reported gaining and the third refers to a lifelong appreciation of music that seemed to have been fostered from a young age for the study participants (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Main music outcomes of being an English chorister.

Sight-reading skills

When ex-choristers looked back on their music training in choir school, of all the skills they gained as a chorister, sight-reading was most frequently mentioned. According to the participants, sight-reading was developed through instrument learning, highly focused rehearsal time, peer pressure, and high expectation from the choirmaster and audiences.

Firstly, choristers’ sight-reading proficiency skills were developed during instrument lessons according to interviewees. The instrumental skill and the overall singing skill were interlinked in their comments, one leading to the other. Good instrumental playing needed to be vocal and include all the nuances of text-based phrasing, while good singing needed the rhythmic discipline and academic rigour of good instrument playing. Therefore, the interviewees believed that a lot of the learning on the singing side came through instrumental work and not always through vocal training. For example, one interviewee suggested that leaning piano directly helped his sight-reading:

If you struggle to sight-read, it is quite helpful to think about it as a piano keyboard so that is why we had two pianos in the boarding house so you could always just go down and play. (1021)

Secondly, sight-reading has to be picked up rapidly because choristers need to sing music of varying genres in daily services with limited time for practice. The quote below demonstrates how sight-reading was used in a rehearsal context:

Sight-reading was not rehearsed as such but simply integrated into the daily training we received. The quantity of music that we needed to get through made rehearsing each item impossible. The music director always strategically placed the most experienced boy in the middle of the stalls so that he was almost used as a guide…The director also often made us listen to the new piece before attempting to sing it. This helped greatly as we would already have the tunes in our heads. Despite making it easier, the music director himself still approached our sight-reading with great patience and helped us by playing our parts on the piano to keep us right. (0511)

One must understand that the choirmaster would expect things to be done efficiently in an hour’s rehearsal and know what must be achieved in that time. As such, it is very rigorous work that has a clear sense of purpose behind it, requiring every member to have proficient sight-reading skills:

The ability to sight-read is absolutely crucial, particularly with things like the psalms. There were definitely times when you just ran out of time to rehearse them so you would sing them in the service…Yes you might remember it from the previous month but you weren’t good at them…[but] had to be up to doing that. (1812)

Thirdly, good sight-reading skills are also developed through peer mentoring. Former christers, as shown in the following quote, held the view that they learned from ‘listening and mimicking’. A ‘monitorial system’ was particularly mentioned by the older generation of choristers who sang in cathedrals and college choirs between the 1940s or 1950s. Interviewees mentioned choristers were not taught as such to sight-read but it was a matter of survival:

The choir was divided into juniors and seniors and probationers…so I was introduced to one of the seniors in the choir. They stood over me in practice and I had to stand next to him and copy him. If I made a mistake, I either got my shins kicked or my ears boxed, so it made me a very, very quick sight-reader. (0111)

As young choristers, many interviewees mentioned that they were asked to immerse themselves in the choral music environment every day and invited to use their prior music knowledge and common sense to make progress through copying their peers:

In your first year you were sat at Winchester, the Dec and Can were on either side of the piano, and then at the bottom of the rehearsal room there was another bench and the probationers had to sit following the music with their fingers, which now I know is a medieval technique. Rather funny that we were made to do it. But we had to follow everything and in our singing lessons we sang through the stuff that the choir was doing, and then in Evensong we had to sit there in silence following it. (3011)

Meanwhile, the pressurised environment created by the choirmaster and the choristers themselves, plus listeners’ high expectations, encouraged and compelled the choristers to develop their skills swiftly and efficiently, as illustrated in the following quotes:

It was just constant practice and just being taught to be professional. You would get a rehearsal and you would go and sing a service and it had to be right. There was no margin for error. (2311)

They (audiences) make a huge difference because doing that stuff at the age of 11 and 12 where you are live on the radio and having people listen to choral Evensong, like two million people. You are vaguely aware that is what you are doing but you are able to just kind of manage your way through it. (1812)

Although the pressures must have been formidable at times, many participants reported that they quickly came to regard these as challenges and faced up to them with determination. On looking back, some interviewees found it had prepared them well for the pressures of later life.

All-round musicianship

This section provides evidence of how being a chorister nurtures an all-rounded musicianship. This includes being able to sing in varying genres and to perform solo in front of large audiences. It also includes the development of instrumental skills (in some cases, an opportunity to learn the organ) and an interest in choral conducting. Twenty-six of the 30 interviewees in this study were boarders who had sung with the choir for 4 or 5 years and who had done more than 20 h of music training each week. However, these findings cannot be generalised to all choristers, especially day choristers who sang less frequently or had fewer years in the choir.

Ability to sing different styles of music

It was clear from the interviews that the modern-day choristers are not only interested in choral music (‘you would never find anybody who wasn’t interested in pop music and stuff’ 2611) but are also interested and capable of engaging in several other forms of music. For example, as one participant mentioned:

We did do a couple of pieces for concerts as a whole choir and were singing in a sort of jazz style. It is a different style, and it requires a different interpretation but certainly it is not beyond the ability of us. I think lots of choristers like the change and they can switch into any style pretty easily. (1311)

Choral music training can give children the ability to sight-read different music genres, as illustrated here:

Having learned to sight-read church music, that enables you to count in time, to be able to read the words and the music at the same time, so I think we have got the skills now to be able to try and sight read lots of different types of pieces. (1121)

Furthermore, this ability to sing in different styles is never lost, according to the study participants, and allows individual choristers to enjoy singing more in later life:

The good thing about the cathedral education and singing in choirs is you can stop for years and then start straight away, like riding a bike. (1411)

The ability to sing solo

During the last 2 years in the choir, senior choristers (usually aged 12 or 13 years) normally perform more solos once their singing technique and music understanding have reached a proficient standard. ‘It wasn’t unusual to sing solos at age 11; to do a small solo part just to get used to it. I think you have got to be a little bit nervous. It is the only thing that I have come across where children and adults perform on the same level, doing the same thing. (2511). For many, singing solos meant conquering one’s shyness and nervousness, but they recognised it as a confidence building process: from being very nervous in the beginning to singing confidently with enjoyment. This demanding emotional process is illustrated in the following quotes:

It was obviously very nerve-racking the first few times. You get very nervous in a cathedral when you are the only one singing and it is hard to develop that skill because normally you can hide behind everyone else’s voices. (1121).

It is quite a theatrical idea and so I remember the experience of walking there and being in this ‘different’ place. I remember I was certainly nervous but it was great, I enjoyed that experience. (2211)

It was the build-up. You are singing the ordinary anthem or whatever it might be: ‘Oh, there is my part, what am I going to do?’ and then you are nervous. My mouth used to go dry and I would say ‘oh, I am going to have to sing this…’ And then you open your mouth and you are all right, but it was the build-up. (1912)

In addition, singing solos made choristers very much aware of the responsibility placed on them by the choirmaster to get their part right in front of an audience:

I think it certainly taught us to just try to do our best. You are responsible for your own actions. You need to get prepared if you know that you have to sing a solo, and you know it is going to be in front of a lot of people. So you would be responsible for yourself and do well. (1021)

Instrumental skills

Choristers were often encouraged to take up two instruments and ideally pass the ABRSM Grade 5 proficiency exam in one of these, according to the participants in this study. The reason for this was related to the standard of musicianship needed in preparation for senior school entrances. Many schools such as Eton College, Radley College, Ampleforth College and Winchester College still expect Grade 6 in the first instrument as a minimum requirement for a musical scholarship. Interviewees did not feel that it was unusual to play two instruments and felt that it helped their vocal development, as shown by the participants quoted below:

It was a very, very musical environment. I remember in my year group there was only one person who didn’t play at least two instruments. It was geared towards daily practice with everyone having rostered music lessons. (3011)

We were taught music theory, that was something compulsory, if you didn’t have Grade 5 theory you would be taught it by the organ scholar during a lunchtime and you had to take the lesson for an exam, it was just something you had to do as a chorister. (0721)

None of the interviewees reached a level to be a professional classical soloist; however, many of them enjoyed just playing for pleasure. Participants also mentioned the instrumental skills gained in the choir school which qualified them to play in a band or chamber group later on.

Piano skills learned in the choir school covered a wide range of genres, and in the last two decades or so the range of instruments offered has become much broader, a fact much appreciated by the choristers:

I remember I was about ten years old and suddenly thinking ‘I can now work a tune out on the piano’. It might have been something that we sang at Evensong. I would go to the piano and I would just work out the melody that we sang without having the music. (1411)

When I was in the choir, we also had access to a spectacularly wide variety of instruments. I myself played the violin and the piano but I had peers who played brass, woodwind, percussion, guitar and pretty much anything in an orchestra. (0511)

This young interviewee (he was 17 years old at the time of the interview) had learned guitar while a chorister purely for his own enjoyment:

I also play the guitar. I don’t do Grades but I just busk. It is good and just depends where you do it. You get different pay because when I went to my friend’s house who lives in Canterbury I had an hour to wait for a train in King’s Cross, I went to the VIP lounge and borrowed someone’s guitar and I made £200 in 40 minutes. (1711)

Interestingly, even though the organ is a special instrument that choristers encounter in their daily life as its sound is the main accompaniment for every service, very few participants in this study actually got a chance to learn it in the choir school. Those who did and became interested in the instrument just gradually picked up the skill through self-tuition or were lucky to have an organist who was willing to train them:

I went in the organ loft and did page-turning which was really great because I got taught all the tricks of the trade, and it was far more interesting. I taught myself organ from a chamber organ in the choir rehearsal room in the cathedral that I was allowed to go over to by myself first thing in the morning. I never had lessons and taught myself. (3011)

I was lucky enough that the organist at New College gave me some lessons during last two years, and when I went to Radley I continued and I still play here at Durham. (0912)

The fundamental keyboard skills they learnt from piano lessons and their musical knowledge absorbed from singing and theory lessons all contributed to the later development of organ skills.

Conducting

Conducting is not normally taught in choir schools according to the participants’ experience, but nine ex-choristers reported that it was something that they watched all the time and that inspired them to take it up later on if they got the chance. As one participant mentioned, ‘I would certainly say watching our choirmaster conduct influenced me and made me want to do it but I didn’t conduct when I was there’. (0912). In the 1940s and 1950s, as the following interviewees remembered, the choirmaster usually doubled as organist, so during the actual services certain boys were discreetly delegated to conduct:

Nowadays you have people conducting the choir, don’t you? We never had a conductor, we just conducted ourselves from the back desks on either side of the choir. We learnt to conduct ourselves unnoticed. So Cyril sat in the organ loft, played the organ and we sang and that was it. I mean the expertise of choristers is beyond belief but that is how we learnt. Because we always did that in practice in those days, quite a lot of ex-choristers were fairly good conductors. (0111)

I am a conductor but I never did it as a chorister. I just worked it out myself. That is not really true because of course I was under A. at Winchester when I was a chorister and under M. at the College Chapel Choir and of course now S. at Trinity. All three of them are very, very brilliant choral conductors. I would say I have learnt from all of them just by watching them while I was singing but I have never been trained. (2611)

It becomes apparent that the choral music experience, as described by the study participants, can be a powerful force for the development of a range of musical skills through immersion in this rich musical environment. Although these young choristers did not realise at the time, having this exposure to conducting allowed them to subconsciously learn from their choirmasters. Later, they could just develop at their own pace and go into music as deeply as they wished, but the foundations had been established.

Lifelong interest in music/appreciation of music

The final theme relating to musical outcomes is the lifelong interest in music that ex-choristers have. An interesting phenomenon that several participants brought up was that at some point, they walked away from church music but they are still enjoying music. Twenty of them did not take music up as a career but instead regarded it as a lifelong interest and hobby. Here is an example from someone who studied for an MSc in Business. This student stopped doing music-related activities after leaving the choir school at the age of 13 years and only returned to singing during her second year in university as she found the cathedral a familiar environment and liked going there:

Since leaving the choir school, I lost the motivation to practice and sing. It has only recently just come back over the past two years. At Durham, in fact, I did no singing in my first year at all because I just decided that I wanted to do other things. I regret that now but yes that is what I did… Now I enjoy singing again in church. I will still take my music up and I will still be singing but I don’t want to do music as my career. (0621)

One interviewee mentioned that although during his time as a student he sang in top-ranking church choirs, he maintained a broad interest in different types of music:

My voice became my sort of first instrument. I loved pop music when I was a chorister. I played in pop groups until a couple of years ago, a Beatles band, a soul band and occasionally still sing in choirs like the one where we made a CD last summer. It is great that it gives you the appreciation of music in general. (1411)

Another former chorister who majored in French & Italian Literature at university tried opera singing in her spare time and made some efforts to prepare for a diploma in singing by taking individual singing lessons:

I had such good singing lessons throughout school so I just thought it would be a good idea to have a singing lesson every other week, just work on pieces then I won’t forget the technique. I am working on diploma pieces at the moment for the step after Grade 8. It is very hard but at some point, I want to work towards it then I will have a repertoire for that. (0621)

However, not everyone found their musical experiences in later life quite so inspiring. These two study participants felt uncomfortable when participating in musical groups where the standards were not of the high quality they were expecting:

For about 20 years of my life I sang in either Durham or in other cathedrals to a very good standard but now I sing in a very small church choir at a much lower standard. I find this really hard. There are a lot of very elderly ladies who are very much wanting to sing well but are often out of tune. You are almost cursed by having a taste for brilliant music and if you don’t reach that level, you are forever thinking I would rather not sing at all than sing at a lower standard.(1411)

I sang with a college chapel choir last year. I had a really fun time but I found it quite frustrating sometimes if people couldn’t sight read at all or there were so many sopranos. It wasn’t the music standard that I would have liked. I feel really bad saying that. (0621)

Additionally, many retired ex-choristers used their strong musical skills to lift their spirits and add to their quality of life, even if they could not sing anymore. The following interviewee considered this as a ‘divine gift’:

All those musical scores I read like a book, so even though I can’t sing I get the CD out and I get the score out, and sing away in my mind. It is a relaxing, soothing wonderful hobby to be able to go anywhere and sing chants…I look upon it as a divine gift that widened and broadened one’s interests and led to other things, not just music. Not just the playing of it but the reading of it and the history of it. Listening to William Byrd’s music for mass gives you a great enjoyment, a great thrill and so it is very helpful in lots of ways for people, particularly in this day and age where there is so much racing about. (0311)

A few of the former choristers even felt dedicated enough in later life to volunteer to organise a wide range of choral events. One ex-chorister, for example, was so inspired that he took on the task to organise all sorts of local and national music events with other former choristers over many decades:

I have had an enormous amount of satisfaction and I have always been enthusiastic about music. I set up the music department in a technical college. I had a very good choir and we used to put on a comic opera every year with the whole college and so on and I enjoyed myself there… I am obviously a classical musician and choral musician…I was actually the chairman of the Federation of Cathedral Old Choristers’ Association. I managed to run two festivals in 1993 and 2005 and they have both gone down extremely well. (0111)

Many commented that they were still keen to keep music as an important part of their life and enjoyed it. Even though their focus may have shifted away from music due to various circumstances, many continued to sing and play instruments as a hobby to enjoy.

However, the study participants pointed out four potential challenges for choristers (Dong, Reference DONG2018): 1) choristers lack time to play and somehow missed a ‘normal’ childhood, 2) many of them had to live away from home which put challenges on family relationships; 3) their schooling after leaving choir school to be educated in non-boarding environments was a difficult adaptation in terms of culture; and 4) despite their growing appreciation of choral music, some choristers found that it was hard to engage with religious worship as the hour-long services in the cathedral when they were young had made them feel reluctant towards religion. However, these considerations are beyond the scope of this paper and will be discussed in subsequent publications.

Discussion

The main musical outcomes of an English chorister’s training are the instilling of strong sight-reading skills, a high level of vocal control and a strong appreciation for music. Their entire musical education is an immersive experience. An illustration of this is that, from the very beginning, young probationers are made to sit through the services for up to 2 years without singing. Hallam (Reference HALLAM1998) lists the importance of aural, cognitive and technical musicianship alongside performance in the development of the professional musician. The paper explains that a variety of these combinations may be required for different tasks or genres of the music profession. Hallam (Reference HALLAM2001) further explains that ‘the process of enculturation into particular musical genres largely occurs through listening to music in the environment. Much of this learning occurs without conscious cognitive awareness; the sounds are simply absorbed’. (p.28). The following discussion deals with choristers’ instrumental skills and musicianship.

The instrumental level that choristers reach is seen as less important, simply a by-product of the choral singing, but there are good reasons for adding instrumental practice, especially piano playing and music theory to a chorister’s already busy schedule. The interview data showed that choristers can apply the knowledge they gain from singing and music theory to making music on an instrument, or vice versa. On the one hand, instrumental learning is one of the mechanisms by which choristers can develop more generalised aural schemata that can be utilised when they have to sight-read new music. On the other hand, for those children who show more talent as an instrumentalist than as a singer, this should be taken into account by parents when considering sending them to a choir school.

Choristers are also encouraged to learn to play the piano, which is seen as very important and in most cases is compulsory. It helps build up a sound image which in turn is likely to help improve their pitch discrimination and vocal accuracy. As the former choirmaster in St. John’s College, Cambridge, George Guest argued that the ability to play the piano, a stringed instrument or a woodwind instrument helps recognise pitch intervals as well as building up a sense of rhythm (Guest,Reference GUEST1998). But more than that, efforts to build up choristers’ instrumental skills need to adapt to the modern tastes of young people and help them enjoy the music-making process individually or as a group.

Our recommendation would be to broaden the choices for choristers to include instruments such as the guitar, saxophone or drum kit. Compared to the piano and violin, these are more popular amongst teenagers and easier to pick up, thus increasing the satisfaction and motivation of continuing. From the interview data, it also seems clear that the level a chorister manages to reach by the end of their school journey is not only based on the years of education in the choir school but is also related to the child’s previous educational background and, very importantly, their parents’ support and guidance. Although choristers make more significant vocal progress and develop music schemata for the particular types of music to which they have been exposed, their music appreciation depends on their personal development for a true desire to enjoy and improve. This is an important point worthy of further exploration considering that several interviewees mentioned dropping their instrument as soon as they left the choir school.

Overall, the study shows that English choristers’ music education remains at a very high standard and is not only limited to choral singing. Along similar lines, David Willcocks (former choirmaster at King’s College, Cambridge, 1957–1974) said in an interview with Doreen Rao: ‘I think that whole five years should be geared towards making a boy a really good musician later in life and opening his ears to the possibilities’ (Rao & Willcocks, Reference RAO and WILLCOCKS1985). Barrett (Reference BARRETT and Barrett2011) similarly concluded that some cathedral choristers would retain their musical skills and engage with music as a singer after leaving the choir school; others might continue their musical engagement as instrumental performers since they still have the skills. The study findings suggest that if ex-choristers choose to do so, they can take up a music career relatively easily; even if they do not decide to become a professional musician, choristers can still have a very high chance of winning music scholarships to their next schools. For example, a large number of scholarships and exhibitions have been awarded to Year 8 children at Exeter Cathedral School. Its reputation for musical excellence also remains high with 15 music awards being won to the UK’s leading senior schools in 2018.Footnote 8 Durham Cathedral had 23 choristers who graduated between 2018 and 2020, 9 of whom received music scholarships to their senior schools (4 girls, 5 boys),Footnote 9 almost 40% of the group were awarded music scholarships.

This study showed that gaining a place as a chorister is highly competitive in some of the choir schools; there might be as many as 60 applicants for just 4 positions. David Willcocks (Rao & Willcocks, Reference RAO and WILLCOCKS1985) insisted that he would select boys ‘with good aural perception’, which is hard to achieve without any preparation, so young children who attend auditions have in most cases been prepared by their parents. On top of this, before a child can be admitted as a probationer into the cathedral choir around the age of 8 years, as well as giving them a vocal trial, the school asks them to sit English and Maths exams to make sure the child can cope with schoolwork. There are many other activities on offer as well as the demanding choir workload. Therefore, the parents themselves have to be fully aware of this and help the child focus on those special strengths the school of their choice is looking for.

This study has focused on the musical benefits of an English chorister education. Out of the 30 participants, only 6 were female. This is because not until 1991 did Salisbury become the first English cathedral to admit girl choristers. The opportunities for female choristers and the equality of funding to support them need to be explored further. However, there is still the fear that introducing girl choral scholarships will somehow dilute or spoil the boys’ experience (Joanna Forbes L-Estrange, 2019Footnote 10 ).

A chorister education is not suitable for every child. Some children, for example, may not be well suited to the boarding school scenario. The demands of being a chorister require a child to have a real aptitude for this kind of lifestyle. These points will be discussed in a separate publication. Something which this paper does not address is the heavy impact that the COVID-19 pandemic has had on the English chorister education. This is a very important topic which ought to be further investigated. Overall, the way that British cathedrals and collegiate chapels train their choristers provides them with a higher standard of lifelong all-round musicianship. As David Willcocks puts it: ‘the time devoted by children to choir singing will never have been wasted, for they have laid the foundation for a lifelong love of music’. (ibid).