Introduction

The research reported in this paper forms part of a larger study that investigated interpersonal interaction amongst teachers, pupils and parents in the context of one-to-one instrumental lessons (Creech, Reference CREECH2006). The overarching purpose of the research reported here is to address the question of what instrumental teachers can learn to do in lessons, in order to maximise positive learning outcomes. For this research, positive learning outcomes were not confined to achievement; rather, positive outcomes were conceptualised in a broader sense, including motivation, self-efficacy, self-esteem, satisfaction, enjoyment of music and attainment. This paper focuses on patterns of interpersonal behaviour amongst teachers and their pupils, investigating whether teacher and pupil behaviours in instrumental lessons might differ in systematic ways that correspond with six interpersonal interaction ‘types’ that were identified in the larger study (Creech, Reference CREECH2009).

Background

Several researchers have, over the past three decades, used observational methods to investigate teacher and pupil behaviour in instrumental teaching, both in classroom and one-to-one contexts (for reviews see Rosenshine et al., Reference ROSENSHINE, FROEHLICH, FAKHOURI, Colwell and Richardson2002; Hallam, Reference HALLAM2006). Effective teaching was conceptualised by Yarbrough & Price (Reference YARBROUGH and PRICE1989) as comprising sequential units of teaching that began with teacher presentation of a task, followed by student response and engagement with the task and concluding with teacher feedback in relation to the student response. Siebenaler (Reference SIEBENALER1997) carried out an observational study, focusing on 13 piano teachers who each recruited one adult student (aged 24+) and one child student (aged 7–11) to take part. A total of 78 one-to-one piano lessons were video-taped and the teacher and student behaviours were analysed. A key finding was that long stretches of uninterrupted student performance ‘often indicated a struggling student without appropriate teacher intervention’ (Siebenaler, Reference SIEBENALER1997, p. 17). Siebenaler concluded that expert teachers, in comparison with non-expert teachers, provided faster-paced sequences of instruction-engagement-feedback, characterised by rapid alternation between teacher feedback and student response.

Duke and Henninger (Reference DUKE and HENNINGER1998) carried out an experimental study, where two groups of beginner recorder students were taught to play a simple melody by either (a) a directive method, focusing on commands describing how the student should perform in a subsequent attempt or (b) a negative feedback method, focusing on identifying performance errors followed by directions for correcting the performance. The participants included 25 fifth- and sixth-grade children and 25 college undergraduates. Following individual lessons, the recorder students completed a short questionnaire that assessed their self-efficacy and positive attitudes towards learning the recorder. The researchers reported that the novice recorder players had positive attitudes about having successfully achieved their musical goals and demonstrated high self-efficacy, irrespective of the teaching approach. The researchers concluded that the salient factor that underpinned positive student experience had been the successful accomplishment of musical goals. However, in both conditions the recorder students had frequent opportunities to respond, the rate of positive teacher feedback was high and, where negative evaluations of previous attempts were offered by the teacher, these were accompanied by specific corrective feedback.

In a follow-up study, Duke and Henninger (Reference DUKE and HENNINGER2002) investigated trainee teacher perceptions of the lessons, testing whether the directive or negative feedback conditions influenced perceptions of the effectiveness of the recorded lessons. Fifty-one undergraduate music teacher trainees took part, viewing one ‘directive’ lesson and one ‘negative feedback’ lesson with a fifth-grade recorder student. The trainee teachers rated both lessons highly positively and again the researchers reported that the feedback condition did not influence perceptions of positive experiences of learning. Expert teachers, according to the findings from this study, gave positive and negative feedback at high rates and offered students many opportunities to respond to feedback and make improvements in their performance tasks.

The concept of scaffolding, whereby students are supported by knowledgeable others (including teachers, peers or parents) has been extensively researched in the wider context of education (for example Needham & Flint, Reference NEEDHAM and FLINT2003). Scaffolding occurs when teachers provide appropriate support that enables students to move beyond their current skill or knowledge, in small and attainable steps. A typology of scaffolding, comprising six stages, was proposed by Wood et al. (Reference WOOD, BRUNER and ROSS1976). Following observations of 30 pre-school children who were guided by their teacher in a block-building jigsaw task, the authors theorised that scaffolding was a process involving several tutor functions. The first of these was ‘recruitment’, whereby the tutor's task was to enlist the problem-solvers’ interest and adherence to the task requirements. The second function was labelled ‘reduction of degrees of freedom’ and involved simplifying the task to the extent that the learner could recognise whether he or she had fulfilled each step of the task requirements. According to this model of scaffolding, further tutor functions included ‘direct maintenance’, ‘marking critical features’ and ‘frustration control’. Direct maintenance referred to the tutor's role in keeping the learner focused on particular objectives and motivating the learner to risk moving out of their comfort zone to a next step. Marking critical features represented the process by which tutors accentuated certain relevant features of a task, drawing attention to discrepancies between the learner's attempt and the desired end product. Tutors also provided scaffolding for learning by offering encouragement and support to alleviate stress or frustration with the task. Finally, the authors identified demonstration or modelling as an important process in scaffolding.

Kennell (Reference KENNELL, Colwell and Richardson2002) proposed that the model put forward by Wood et al. (Reference WOOD, BRUNER and ROSS1976), applied in the context of instrumental learning, would include recruitment strategies that synchronised the attention of pupil and teacher, marking critical features of tasks, manipulating the difficulty level of tasks, modelling performance, setting goals and providing support for the pupil by engaging in dialogue intended to reduce frustration.

In order to maximise the potential for effective learning, instrumental pupils need teachers to scaffold their development in a range of ‘aural, cognitive, technical, musical communication and performing skills’ (Hallam, Reference HALLAM2006, p. 169). In this vein, Colprit (Reference COLPRIT2000) reported that expert teachers, conceptualised as those who accomplished positive change in their students’ performances, structured their lessons in small attainable steps that led sequentially to the attainment of goals. Colprit makes the salient point that the complexity of the teaching–learning process makes identification of specific features of effective teaching problematic.

Diagnostic skills and the use of modelling may both contribute to successful scaffolding of student learning, while the effectiveness of these strategies may be mediated by the teacher's musical competence and teacher affect (Brand, Reference BRAND1985; Saunders, Reference SAUNDERS1990). However, although there may be some cultural differences in teacher and student behaviour (Benson & Fung, Reference BENSON and FUNG2005), observational evidence from the USA (for example, Kostka, Reference KOSTKA1984; Kennell, Reference KENNELL1992) suggests that the most frequent teacher behaviour is directive verbal diagnosis, with little time devoted to modelling. Salzberg (Reference SALZBERG1980) contributed some evidence to support the view that verbal diagnosis has an important role to play in scaffolding instrumental learning, reporting that university student string players produced more accurate intonation in response to verbal feedback than following modelled performance. Nevertheless, a substantial body of evidence supports the view that effective learning amongst instrumental students is supported when teachers model processes such as identifying difficulties and generating problem-solving strategies, as well as when they model technical or musical aspects of desired performances (see, for example, Kostka, Reference KOSTKA1984; Dickey, Reference DICKEY1991, Reference DICKEY1992; Hallam, Reference HALLAM2006).

Praise, too, has been found to be an effective and enduring form of scaffolding, but most notably when accompanied by physical, ‘hands-on’ corrective prompts. Salzberg and Salzberg (Reference SALZBERG and SALZBERG1981) carried out an experiment with five elementary school-aged violin pupils, comparing corrective feedback with praise. The researchers reported that praise was always as effective as corrective feedback and that when physical prompts were used in conjunction with praise, for extended periods, the effects were positive and sustained.

The quality of teacher feedback, in particular, has been the focus of much research concerned with teacher–student interaction. There is a wealth of empirical evidence in many diverse educational contexts to support the view that students who develop sustained and deep engagement in a given domain are supported in making attributions for success to effort and the correct use of learning strategies (Fryer & Elliot, Reference FRYER, ELLIOT, Schunk and Zimmerman2008).

In a musical context Colprit (Reference COLPRIT2000) and Duke and Henninger (Reference DUKE and HENNINGER2002) have noted that the quality of teacher talk may distinguish expert teachers from their less-expert counterparts. In particular, expert teachers have been found to provide specific attributions for student performance on tasks, for example making detailed reference to tone quality, intonation, expression, phrasing or articulation.

In summary, the evidence strongly suggests that instrumental learning is supported when teachers implement a range of scaffolding strategies, including specific, honest and positive feedback and verbal diagnosis accompanied by high quality modelling and hands-on corrective prompts (for example, Colprit, Reference COLPRIT2000; Kennell, Reference KENNELL, Colwell and Richardson2002; Hallam, Reference HALLAM2006).

Methods

Typology of interpersonal interaction

As noted above, the research reported here forms part of a larger study (Creech, Reference CREECH2006) that explored the contribution of interpersonal interaction to teaching and learning outcomes amongst 263 violin teachers and their pupils. The teachers taught in private studios, independent schools, state-funded music services and junior conservatoires, with pupils aged 8–18 whose levels of ability ranged from beginner to diploma level. Their teaching experience ranged from one year to over 30 years; 50% had over 15 years of experience. Several teaching methods and approaches were represented; 177 (67%) teachers taught by ‘no specific method’, 49 (19%) taught by the Suzuki method, and the remaining 37 (14%) taught by a range of other specific methods. Some teachers had more than one pupil who participated in the research. In total, 337 pupils and their parents took part in the study, thus making it possible to examine interpersonal interactions amongst 337 teacher–pupil–parent trios.

A model of six interpersonal interaction types was developed, using quantitative and qualitative methods to explore the teacher–pupil–parent interactions (Fig. 1). The model was developed within a systems theory perspective and based on a cluster analysis of measures of interpersonal control and responsiveness, in-depth interviews and observations of lessons (see Creech, Reference CREECH2009 for full details of development of the model). Systems theory is characterised by concepts of reciprocity and holism (Tubbs, Reference TUBBS1984). Systems theorists place an emphasis on understanding the constituent parts of a system in relation to the dynamic properties of the whole unit (Pianta & Walsh, Reference PIANTA and WALSH1996), which in the context of this study was conceptualised as the teacher–pupil–parent partnership. Circular communication processes develop which not only consist of behaviour but which determine behaviour as well. ‘When individuals communicate, their behaviours will mutually influence each other’ (Van Tartwijk et al., Reference VAN TARTWIJK, BREKELMANS and WUBBELS1998, p. 608). From this perspective, an individual's particular interpersonal style may be seen as both causing and resulting from a web of complex interactions. For example, Creech and Hallam (Reference CREECH and HALLAM2003) describe ‘collective efficacy’, whereby teachers who were secure in their perceived capabilities invited and supported parental involvement, which in turn fostered self-efficacious beliefs and supportive behaviours amongst parents and pupils.

Fig. 1 Teacher–pupil–parent interaction types in instrumental learning

The six different interpersonal interaction types identified in the larger study (see Fig. 1) represented diverse interpersonal relationships. Types 1, 2 and 4 were characterised by a didactic master–apprentice framework. Types 1, 2 and 3 were each conceptualised as a primary dyad plus a third party, while Type 4 was represented as two primary dyads connected by one common member. Type 5, the least successful in terms of teaching and learning outcomes that included attainment, motivation, self-efficacy, self-esteem, enjoyment and satisfaction, was characterised by very little communication between any two of the three individuals. In contrast, Type 6 was characterised by reciprocity amongst all three participants, with teachers who were receptive, caring and yet supportive of autonomous learning. The highest musical attainment levels were found amongst Type 6. However, while no single type of interaction consistently produced the best outcomes for teachers, pupils and parents alike, overall the most effective teaching and learning outcomes (noted above) were found amongst those classified as ‘harmonious trios’ (Type 6) representing a parent–professional–child partnership characterised by reciprocal communication, mutual respect and child-centred goals (Creech, Reference CREECH2006).

Video observations

Case study examples representing each of the six interpersonal types were identified as participants for the observational study. To some extent this was a self-selecting sample as participants were drawn from a pool of 98 teacher–pupil–parent trios who had indicated on the initial questionnaire their willingness to participate in observations. The case study participants were selected as far as possible to be representative of the gender balance, pupil age and teaching methods found amongst the larger sample. Eleven violin teachers (eight female and three male) and their pupils aged 8–16 (15 female and eight male) were observed and digitally recorded during a total of 23 one-to-one lessons (Table 1). Six teachers taught by ‘no specific method’, three identified themselves as Suzuki teachers and two taught by ‘other specific’ methods. The observed lessons all took place at the time and venue where they ‘normally’ happened on a weekly basis, including private studios, independent schools, state sector schools, Saturday music centres and one junior conservatoire.

Table 1 Participants in the video observations

Digital recordings of 30-minute lesson segments were analysed with the aid of the software package Scribe 4.1.1 (Duke & Stammen, Reference DUKE and STAMMEN2009), first using an event-sampling approach, using a pre-defined checklist of lesson behaviour (see Table 2) derived from Hallam (Reference HALLAM1998).

Table 2 Checklist of observed lesson behaviours

These results were then verified using a time-sampling approach. The video recordings were watched repeatedly, focusing first on the teacher behaviours and then on the pupil behaviours. The video tapes were stopped at 5-second intervals and the observed behaviour at that point was coded accordingly. Finally, qualitative field notes from the observations were used to triangulate the quantitative coded results. For the purposes of this paper, the results of the time sampling, whereby behaviours were coded at 5-second intervals, are reported. Only those behaviours that directly related to technical and musical issues are reported and discussed.

Findings

Behaviour in the observed lessons was coded in five overarching categories (Table 3). Pupils played in the lessons for an average of 38% of the time, either on their own or accompanied by their teacher. An average of 29% of lesson time was spent with teachers talking, either in a directive way, diagnosing pupil performance or providing feedback. Teacher feedback was coded as ‘attributional’ when teachers attributed success or failure in performance outcomes to specific strategies or effort (e.g. ‘well done, because when it wasn't quite sharp enough you moved your finger up, just here’). Conversely, feedback that was positive or negative but not attributed to any specific cause (e.g. ‘very good indeed’) was coded as ‘non-attributional’. Teacher scaffolding, accounting for an average of 28% of the time, included modelling on the violin or singing, playing along with the pupil on the violin, accompanying on the piano or providing hands-on practical help (e.g. guiding the bow, assisting with posture). Teacher questioning, taking an average of 9% of the time, included open questions, rhetorical questions where agreement from the pupil was required, or questions intended as a means for checking the pupil's understanding. Finally, pupil talk accounted for an average of 3% of the time and included agreement or disagreement with the teacher, contributing own ideas, self assessments and choosing what to play.

Table 3 Overall percentage of time engaged in different behaviours

Table 3 demonstrates that in all of these categories, particularly the amount of time pupils played and teachers provided scaffolding, there was considerable variability. However, an analysis of variance, comparing the mean percentage of time in each coded category across the six interpersonal types did not reveal any statistically significant differences with regards to these overarching categories of behaviour. Nevertheless, statistically significant differences were found with respect to sub-categories related to open questioning, scaffolding in the form of playing along with pupils and feedback that was specific and attributional; these are discussed in the following section.

Teacher questioning

Figure 2 suggests that the greatest proportion of time devoted to teacher questioning was found within Type 6, the ‘harmonious trios’. A one-way between-groups analysis of variance was carried out, comparing the extent and nature of teacher questioning, across the six interpersonal types. Statistically significant differences in the percentage of time were found in respect of open questioning (F(5, 17) = 4.8, p = 0.007) and seeking agreement (F(5,17) = 3.4, p = 0.03). Post-hoc tests indicated that overall the greatest differences were in respect of open questioning, with Type 6 ‘harmonious trios’ using more open questioning than the Type 1 ‘solo leaders’ (mean difference 2.42), the Type 3 ‘dynamic duos’ (mean difference 2.28) and the Type 5 ‘discordant trios’ (mean difference 2.40).

Fig. 2 Differences between interpersonal types in teacher use of questioning

Scaffolding

A one-way between-groups analysis of variance revealed that the only statistically significant difference between the interpersonal types in relation to scaffolding strategies was in respect of playing along with the pupil (F(5,17) = 3.5, p = 0.022). The greatest difference was found between type 1 ‘solo leaders’ and type 6 ‘harmonious trios’ (mean difference – 11.63). Figure 3 demonstrates that in Type 1 and 5 lessons teachers played along with their pupils more than teachers in other types, while in Type 6 lessons teachers spent more time providing hands-on practical help. Scaffolding in Types 3 and 4 was provided for the most part through accompanying at the piano, while in Type 2 scaffolding was mainly in the form of modelling on the violin (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Time spent in scaffolding behaviour

Teacher talk

The percentage of time devoted to facets of teachers’ talk, including directions to play, diagnoses and attributions for positive or negative performance outcomes was compared across the six types (Fig. 4). Differences in respect of directions, diagnoses and non-attributional positive and negative feedback were found to be non-significant.

Fig. 4 Teacher talk amongst the six interpersonal types

With respect to attributional feedback, statistically significant differences were found between ‘harmonious trios’ (type 6) and each of the other types (F(5,17) = 13.8, p < 0.0001) (Table 4).

Table 4 Mean percentage of lesson time devoted to attributional feedback

Pupil talk

As noted above (Table 3) a very small percentage of time was devoted to pupil talk and an analysis of variance did not reveal any statistically significant differences. Figure 5 suggests that pupils devoted more time to self-assessment within Type 6, while in Type 4 they responded to the teacher with their own ideas, more than amongst the other types. Overall, pupils rarely expressed disagreement or agreement with the teacher and in Types 1 (solo leader) and 5 (discordant trio) pupils did not ask questions. The greatest variety of pupil talk, including more self-assessment than amongst the other types, was found in Type 6 (harmonious trio) lessons.

Fig. 5 Percentage of time pupils talked during the lessons

Pupil playing

A considerable amount of lesson time was spent with pupils playing their instruments (Table 5).

Table 5 Percentage of time pupils were playing during the lessons

As noted above, where ‘accompanied by teacher at the piano’ and ‘teacher plays along on the violin’ were coded as scaffolding strategies, statistically significant differences were found between the interpersonal types for ‘teacher playing along’ (F(5,17) = 3.5, p = 0.022). No other significant differences were found, although Fig. 6 suggests that during the ‘solo leader’ lessons (Type 1) there was more interplay between playing alone and playing with scaffolding from the teacher, in comparison with the other types.

Fig. 6 Percentage of time pupils played during their lessons

Pace of the lessons

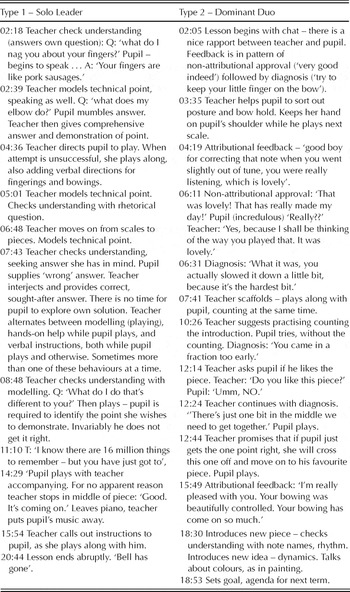

Overall, behaviour patterns were seldom pupil-led and could most frequently be characterised as teacher instruction–pupil response–teacher feedback. However, there was evident variability in the extent to which teachers allowed space for pupil response, as well as with respect to qualitative aspects of the teacher feedback. Table 6 demonstrates an extract from a Type 1 lesson, where the teacher was highly directive, to the point that the pupil's responses were scarcely acknowledged. In contrast, the extract from a Type 2 lesson (Table 6) demonstrates a clear pattern of teacher initiation, pupil response and teacher feedback that, to greater extent, was specific. The teacher style in this lesson was authoritative, yet characterised by responsiveness to the pupil.

Table 6 Field notes from Type 1 and Type 2 lessons

In Type 3 a clear pattern of teacher initiation, pupil response and teacher feedback was again discernible. There were longer stretches of pupil playing in this lesson and the feedback stayed focused on diagnosis of technical issues, diagnosing problems and scaffolding solutions using modelling in particular. Feedback tended to be non-attributional; where attributions were made they were to factors such as the quality of the instrument, over which the pupil had no control (Table 7). The Type 4 lesson similarly focused on technical issues, although a significant part of this lesson was devoted to playing duets together with evident pleasure, exploring musical compositional devices through this medium. Like the Type 2 lesson, there was an evident responsiveness on the part of the teacher towards the pupil's contributions, both verbal and musical.

Table 7 Field notes from Type 3 and Type 4 lessons

Finally, field note extracts in Table 8 demonstrate a difference between Type 5, characterised by low responsiveness, and Type 6, where the teacher and pupil interact, seeking solutions to problems together. The Type 5 teacher's feedback is almost always non-attributional, yet judgemental, leaving the pupil with no specific information as to how to improve or solve a problem. The pupil is not, at any point in the lesson, provided with space in order to articulate ideas or formulate questions. In contrast the Type 6 teacher provides diagnostic feedback, attributing successful outcomes to specific strategies and providing specific information as to how to progress. Furthermore, the Type 6 teacher allows the pupil space to experiment with tuning and other technical issues, report on what has been practised that week and contribute to setting practice goals. Whereas the Type 5 lesson fostered evident anxiety in the pupil, the Type 6 lesson fostered enjoyment and curiosity, even where the task was difficult and challenging.

Table 8 Field notes from Type 5 and Type 6 lessons

Discussion

The evidence presented here provides some insight into what happens behind the closed doors of one-to-one instrumental lessons, in terms of the nature of the behaviours and interactions teachers and pupils engage in, in pursuit of positive teaching and learning outcomes. This paper suggests that behaviour in instrumental lessons may indeed differ in some systematic ways that correspond with six interpersonal interaction ‘types’ that were identified in the larger study (Creech, Reference CREECH2006).

Overall, in accordance with previous research (for example, Yarbrough & Price, Reference YARBROUGH and PRICE1989), behaviour patterns in the lessons were seldom pupil-led; generally pupils listened passively to teachers, responding to direct instruction and diagnosis. As previous researchers have noted (Kostka, Reference KOSTKA1984; Kennell, Reference KENNELL1992; Benson & Fung, Reference BENSON and FUNG2005), teachers talked (including questioning) more than they provided scaffolding for pupil activity. Furthermore, as previous research would suggest (Duke & Henninger, Reference DUKE and HENNINGER2002), some types (e.g. Type 1) were characterised by a faster pace than others, with a more dynamic interplay between different styles of scaffolding, in particular. However, in contrast to the findings from previous research, a faster pace did not always imply more positive outcomes. Rather, the fast pace established during the Type 1 lessons had the potential to obscure the pupil voice, limiting opportunities for the pupil to experiment or to formulate and articulate their own ideas. In this vein, Type 2 and Type 6 lessons, where there was less use of scaffolding strategies than in Type 1, were the lessons where the pupils were found to choose what to play and to ask questions more than in other types.

A comparison of Type 1, characterised by highly directive teachers and reticent yet compliant pupils, with Type 6, characterised by teachers who were responsive and open to pupil views, highlights diverse behaviours that align with a difference between a didactic master–apprentice model of teaching as contrasted with a facilitative student-centred model. Hallam (Reference HALLAM1998) proposed a series of possible models developed from Pratt (Reference PRATT1992), including engineering (delivering content); apprenticeship (modelling ways of being); developmental (cultivating the intellect); nurturing (facilitating personal agency); social reform (seeking a better society). Arguably, Type 1 may be conceptualised as aligning with the most teacher-dominated of these models, while Type 6 may be conceptualised as corresponding with the most student-centred model. In this vein, while Type 1 teachers did provide more extensive scaffolding than in Type 6, their lessons were to a large extent teacher-focused, characterised by more directive talk than open questions or checking understanding. The pupil voice, both musically and verbally, was largely absent from these lessons. Pupils did not ask questions and did not tune their own instruments. Furthermore, they were not given many opportunities to play alone or to explore and experiment with new ideas. In contrast, Type 6 teachers devoted more time to questioning using a range of styles. Pupils were given time to experiment with tuning their own instruments and with implementing new ideas. These pupils engaged in self-assessment and asked questions more than in other types. Perhaps the most distinctive feature of the Type 6 lessons was the specific feedback provided by teachers, attributing outcomes – be they positive or negative – to specific strategies or to effort. In this way pupils were provided with information that they could apply effectively in their progression towards becoming self-regulating, autonomous learners.

As noted in the introduction to this paper, the overarching purpose of this investigation was to contribute to our understanding of what instrumental teachers can learn to do in lessons in order to maximise positive learning outcomes. With the exception of Type 5, where there was little evidence of shared purpose and which was characterised by discord and anxiety, all of the observations highlighted styles of behaviour and teacher–pupil interaction that arguably have a justified place within a teacher's ‘repertoire’ of strategies. The complexity of teaching and learning processes, considered together with the great diversity amongst any group of individual learners, is such that effective teaching may be underpinned by just such a wide-ranging repertoire of interpersonal behaviours.

From a systems theory perspective, the differences that were found with regards to style of teacher questioning, use of ‘playing along’ scaffolding strategies and, in particular, the use of attributional feedback could be interpreted as manifestations of reciprocal interpersonal processes, rather than as characteristics of individual teachers. An underpinning principle of systems theory is that if one part of a system changes this will in turn effect reciprocal change throughout the whole system (Tubbs, Reference TUBBS1984). Thus, teachers who wish to effect positive change with regards to teaching and learning processes may choose to do so by, for example, developing a flexible interpersonal style that accommodates a range of scaffolding, questioning and feedback strategies. Most importantly, teachers may use the model of interpersonal interaction as a reflective tool, supporting the development of awareness of when various scaffolding and feedback strategies may be used to greatest effect in teaching and learning contexts.

The analysis offered in this paper is limited by a small sample size that comprised unequal numbers of lessons within each interpersonal type. Furthermore, the participants in the study were to a large extent self-selecting, which may have biased the results. It is also important to acknowledge that the very presence of the researcher observing the lesson may have changed the interpersonal dynamic and influenced particular behaviours. Furthermore, the interpretation of the observed lessons is one researcher's perspective – a researcher who herself is an experienced instrumental teacher and teacher educator. While every attempt was made to create a robust analysis, a potential bias in interpretation must be acknowledged. A further salient consideration that was outside of the scope of this study is related to gender issues. There is a real need for future research that examines potential gender biases in instrumental teaching.

Notwithstanding these limitations, the observations reported here, within the framework of the model of interaction types, provides teachers with a tool for reflecting on and widening the scope of their own teacher–pupil behaviour and interactions. Teachers and pupils need not become entrenched in fixed patterns of interaction behaviour that potentially place constraints on teaching and learning outcomes. Rather, instrumental teachers have the option to widen the scope of their behavioural repertoire, thereby creating opportunities for enhancing both pupil engagement with learning and teacher satisfaction. For example, teachers may re-frame or vary their style of feedback, they may encourage student questioning and self-assessment and they may create space for experimentation with technical solutions and exploration of musical ideas. Altering patterns of lesson behaviour in these ways offers the potential for students and teachers to migrate to alternative interaction styles that may foster greatly enhanced learning outcomes.