Introduction

For musicians, negotiating the emergence from higher education to professional life presents many challenges. This rite of passage involves an ‘emotional reorganisation’ that can entail loss, risk and anxiety, as well as excitement and anticipation of future possibilities (Lucey & Reay, Reference LUCEY and REAY2000). Factors influencing successful transition into professional performing careers include support and encouragement from parents, peers, teachers and institutions, strong self-concept as a musician and coping strategies that underpin perseverance and self-discipline within a highly competitive domain (Burland & Davidson, Reference BURLAND, DAVIDSON and Davidson2004; MacNamara et al., Reference MACNAMARA, HOLMES and COLLINS2006).

This article explores the transition from music undergraduate to professional status and addresses the question of how higher education experiences might facilitate this process. The research reported here formed part of a larger project, Investigating Musical Performance (IMP): Comparative Studies in Advanced Musical Learning (Welch et al., Reference WELCH, DUFFY, POTTER and WHYTON2006), a two-year comparative study of advanced musical performance. The IMP project was devised to investigate how classical, popular, jazz and Scottish traditional musicians deepen and develop their learning about performance in undergraduate, postgraduate and wider music community contexts. For the purposes of this paper, thematic analyses were carried out on interview data from 27 undergraduate and portfolio career musicians representing all four of the focus genres. Differences and commonalities between transition experiences of musicians from the four genres were noted and the potential for higher education music institutions to support successful transitions was explored.

Transition has been described as a process rather than a specific event (Hallam & Rogers, Reference HALLAM and ROGERS2008). This process opens up a space in the imagination where the individual has the capacity to anticipate future possibilities in relation to present action and to begin to develop effective coping strategies for dealing with the real or imagined challenges lying ahead (Giddens, Reference GIDDENS1991; Lucey & Reay, Reference LUCEY and REAY2000). A body of research concerned with transitions throughout formal education suggests that transition experiences may be cumulative and furthermore that key ingredients for successful negotiation of critical transitions are an enthusiasm for learning, confidence in oneself as a learner and a sense of achievement and purpose (Galton et al., Reference GALTON, MORRISON and PELL2000).

Various researchers, including Bloom (Reference BLOOM1985), Sosniak (Reference SOSNIAK and Bloom1985, Reference SOSNIAK, Ericsson, Charness, Feltovich and Hoffman2006) and Manturzewska (Reference MANTURZEWSKA1990), have proposed the idea that musicians negotiate several transition points, passing through distinct phases of development typically characterized by spontaneous musical expression and exploration followed by periods of guided instruction, goal oriented commitment, identification and the development of artistic personality (Hallam, Reference HALLAM2006). It has been acknowledged that the acquisition of musical expertise throughout these phases requires considerable long-term investment of time and several studies have contributed to our knowledge of how best to support young musicians in sustaining their musical interest and motivation (Sosniak, Reference SOSNIAK, Ericsson, Charness, Feltovich and Hoffman2006). In particular, the crucial role of parental support has been well-documented (Csikszentmihalyi et al., Reference CSIKSZENTMIHALYI, RATHUNDE and WHALEN1993; Creech, in press) , as has the influence of extended family (Feldman & Goldsmith, Reference FELDMAN, GOLDSMITH and Fowler1996), instrumental or vocal teachers (Creech & Hallam, Reference CREECH and HALLAM2003) , peer groups (Feldhusen, Reference FELDHUSEN, Sternberg and Davidson1986) and role models (Sosniak, Reference SOSNIAK and Howe1990).

The importance of transition points in the pathway of musical expertise development has been acknowledged; ‘the longer a person engages in musical activities, the more expert they are likely to become as performers, assuming that they pass through each of the delineated stages successfully’ (Papageorgi et al., 2007: 4, italics added). The question of why some individuals successfully negotiate transitions from one phase of musical development to another (in the sense that they sustain engagement with music and continue to develop musical skills and artistry) while others do not has been investigated (Davidson et al., Reference DAVIDSON, HOWE and SLOBODA1995; Hallam, Reference HALLAM1998; O'Neill, Reference O'NEILL2002). Much of this research has been concerned with critical transitions during the formative years of musical development, for example between the second and third phases proposed by Manturzewska (Reference MANTURZEWSKA1990) of intentional, guided development (approximately between the ages of 6 and 13) and the hypothetical formation of an artistic personality (approximately between ages 13 and 23). Transition into this latter phase of development, characterised by greater demands in terms of deliberate practice, performance and competition, has been described as the mid-life crisis of young musicians, when the need to acquire or disown the interest in music becomes paramount (Bamberger, Reference BAMBERGER and Feldman1982).

Little research exists that has specifically investigated what factors are implicated in the successful management of the subsequent transition ‘between developing serious competence and then moving further toward the limits of expertise’ (Sosniak, Reference SOSNIAK, Ericsson, Charness, Feltovich and Hoffman2006: 297), which is interpreted here as corresponding with the transition from higher education contexts into professional performance careers.

One of the few studies to address this particular musical transition was carried out by Burland & Davidson (Reference BURLAND, DAVIDSON and Davidson2004) who undertook a follow-up to an earlier study concerned with motivation in children's musical development (Davidson et al., Reference DAVIDSON, HOWE, MOORE and SLOBODA1996, Reference DAVIDSON, HOWE and SLOBODA1997). In the second study, carried out 8 years later when the participants were between 17 and 26 years old, 20 semi-structured interviews were carried out with individuals who had been identified in the earlier study as children with high potential in music and who had attended a specialist music school in the UK. Six of the young musicians had decided against pursuing musical careers; thus the opportunity arose to compare retrospective accounts of those who had made the transition from music student to music professional with those who had taken alternative pathways (Burland & Davidson, Reference BURLAND, DAVIDSON and Davidson2004). A key finding from this study was that ‘the most important factor influencing whether the musicians . . . went on to pursue a professional performing career is the role of music as the central determinant of self-concept . . . . it seems that the importance of music to self-concept develops during the later stages of training’ (Burland & Davidson, Reference BURLAND, DAVIDSON and Davidson2004: 243). The influence of teachers, parents and peers was found to have sustained importance, while music education institutions were found to ‘clearly shape the musician and his or her self-concept’ and ‘to influence whether they proceed through the transitional phase successfully’ (Burland & Davidson, Reference BURLAND, DAVIDSON and Davidson2004: 244).

Transition from music student to music professional was also investigated by MacNamara et al. (Reference MACNAMARA, HOLMES and COLLINS2006) who identified psychological characteristics that facilitated successful transition experiences. Eight classical musicians were interviewed, offering insights into the ‘fear and frustration often associated with beginning a career as a performer’ as well as the ‘financial and practical constraints of forging a career in the music industry ‘(MacNamara et al., Reference MACNAMARA, HOLMES and COLLINS2006: 299–300) and suggesting that salient psychological characteristics at that particular transition point included versatility, self-belief, planning, perseverance and interpersonal skills.

The research reported here adds to the existing knowledge related to key transitions in the lives of musicians and specifically how higher education experiences may diminish or enhance the transition experience; in particular it is concerned with the transitional process of acquiring and establishing a professional artistic identity. Significantly, this study includes accounts from musicians representing a broad spectrum of musical genres, thus affording the opportunity to identify cross-genre differences or commonalities in transition experiences. Furthermore, as popular music and Scottish traditional music are relative newcomers to the higher education context, this research offers insights into how higher education establishments that focus on musical genres other than classical may best support their students in the rite of passage from student to professional.

Methodology

Twenty-seven semi-structured in-depth interviews were undertaken with portfolio career musicians (N = 15) who reflected on past experiences of transition as well as undergraduate (N = 12) music students who could be said to be ‘in transition’. The participants were ‘case studies’ drawn from a larger sample of musicians (N = 244) who had all completed a survey of attitudes relating to teaching, learning and expertise in music (Welch et al., Reference WELCH, DUFFY, POTTER and WHYTON2006). The musicians represented four musical genres that included classical, Scottish traditional, jazz and popular. A profile of the participants is given in Table 1.

Table 1 Profile of interviewees

*ST = Scottish traditional music.

Face-to-face interviews took place in the UK between January and April 2007. Lasting between 60–90 minutes each, the interviews were transcribed and a thematic analysis was undertaken using the approach known as empirical phenomenology, following the guidelines laid out by Cooper & McIntyre (Reference COOPER and MCINTYRE1993). The underlying principle of this approach is that theorising is based on participants’ own descriptive accounts of the phenomenon being investigated. Transcripts were read in sample batches of ten, and themes relating to the research questions were identified. These themes were grounded in the text, and translated into coding categories drawn directly from the text itself. For example, text concerned with anxiety relating to one's ability to attain professional standards of music-making was coded as ‘self-doubt’ and then grouped together with other themes such as ‘competition’ and ‘financial hardship’ to create a cluster of themes representing the challenges underpinning transition that were articulated by the participants. As each new sample of transcripts was read the coding scheme was tested and revised. The process was repeated until all text had been examined in relation to the coding scheme and points of difference and similarity amongst texts had been identified. NVivo software (Bazeley, Reference BAZELEY2007) facilitated the coding process and organisation of the qualitative data. Coding reports were generated by NVivo and exported into SPSS (Field, Reference FIELD2000) in order to facilitate a comparison of the prominence assigned to various themes in the musicians’ accounts.

Although interview studies are limited in that they can only ever offer insights related to what participants choose to report, they have the potential to allow insight into the issue at hand through the voice of those whose experiences we are interested in. Recognising that ‘we can never identify and measure the full context of anyone's life, even in the present, and interpretation of data can only be as well informed as possible’ (Freeman, Reference FREEMAN, van Lieshout and Heymans2000: 236), the analysis reported here was intended to probe the issue of transition in order that these findings may be converged with findings across different methodologies.

Findings

Themes that were identified fell into two broad areas. These were (1) challenges associated with forging a career in music performance and (2) mitigating factors that underpinned successful transition experiences (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Challenges and mitigating factors mediating the process of transition from student to professional

Challenges

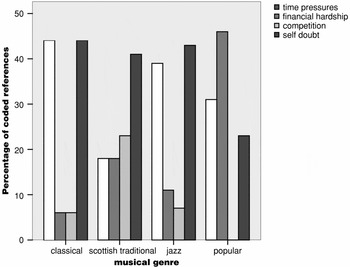

Challenges associated with forging a career in music performance included pressures on time, financial hardship, professional competition and self-doubt (Fig. 2). For musicians in all genres, pressures on time and self-doubt were particularly strong themes, although Scottish traditional musicians placed less emphasis on time pressures than musicians from other genres and popular musicians placed less emphasis on self-doubt than the other genres. Financial hardship was given the greatest weight by popular musicians, while competition was given more prominence in the accounts of Scottish traditional musicians than those from other genres. However, these comparisons are descriptive of these cases only and should not be generalised, as the sample size in each genre was very small.

Fig. 2 Perceived challenges in establishing a music performance career (percentages of coding references within each musical genre)

Pressure on time

Irrespective of whether the participants were working as musicians or in non-music jobs, difficulties associated with the need to continue to devote considerable amounts of time to professional development – and private practice in particular – were emphasised. When other pressures such as family commitments, commitments to further study and time spent working were brought to bear, it became increasingly difficult to sustain personal professional development (Table 2).

Table 2 Pressures on time

Shortage of time for practising was found to be a feature of the lives of many professional musicians: ‘I practise as much as I can, as time will allow . . . I can cut corners . . . But really, I'm always short of time’ (classical, portfolio musician). Donna, a professional classical singer, described how she felt when faced with insufficient time to prepare: ‘I always feel like I've kind of short-changed the music.’

The strong message from all of the musicians was that practising continued to be a foundation stone of musical development throughout higher education and beyond; some of the undergraduates recognised that finding time to practice, post-graduation, could pose problems: ‘I think making time to practice will be a big one - it seems hard now, but actually it's not at all’ (classical, undergraduate).

Self-doubt

Although the theme of self-doubt was found to be less prominent in the accounts of popular musicians it was clearly perceived to be an important issue for musicians from all genres (Table 3).

Table 3 Self doubt

Doubt as to whether one could live up to one's own expectations as a performer, as well as the expectations of audiences, was articulated several times. Henry, a classical musician who had branched out into popular genres, described how the performance stakes continued to rise:

As you get older it gets a bit more serious somehow and those performances start becoming more anxiety ridden rather than just purely for pleasure. You think, ‘I've got to go out there and perform to a certain standard’. (portfolio musician)

This view was elucidated by Bridget, who made the salient point that her self-doubt increased in proportion to her awareness of potential musical and technical boundaries.

What's making you nervous is your own expectations and knowledge of what's achievable . . . you have an imbalance between what you know is potentially possible and what you can do. (classical, portfolio musician)

As musicians gained in experience, there was a sense that they believed themselves to be only as good as their last performance, constantly having to reaffirm their status as professional musicians. Despite considerable experience and success as a professional musician, the absence of formal qualifications caused Jessica, a jazz musician, to doubt her technical ability.

I must have been playing for nearly 30 years . . . So I feel very comfortable at the piano, but I'm conscious of the fact that I only ever took formal exams up to Grade 7 and I, you know, stopped doing exams and I've never, kind, of studied the piano to a high level so I feel a bit nervous about that. (portfolio musician)

Jessica also provided an example of how conflicting identities have the potential to foster self-doubt; in her case it was her identity as a mother that caused her to question her musician identity.

I was part of the house band and I was very heavily pregnant with my second son, and this young guy came along to play and he sat in on the piano and he was fantastic and I just, suddenly, my confidence went and I thought ‘what am I doing here’ you know? ‘I should be at home nest building. Who am I kidding, going out and trying to gig?’

Financial hardship and professional competition

Financial hardship was alluded to by musicians from all musical genres. Amongst some musicians there was a sense of resignation to the fact that they would never achieve substantial financial recompense from the lifestyle they had chosen, while for others this was a difficult issue. Amongst all but the popular musicians, the music profession was deemed to be highly competitive; this appeared to be a bigger worry to the undergraduates than it was for the professional musicians who had found their niche, establishing careers that involved a full gamut of musical activities (Table 4).

Table 4 Financial hardship and competition

Mitigating factors

Several themes emerged that were interpreted as factors which mitigated the challenges of making the transition from student to professional (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3 Factors that ease the transition into professional musical performance careers – percentages of coding references within each musical genre.

Accounts from musicians representing all four genres included an emphasis on the importance of personality factors. A primary theme for all but the popular musicians was the importance of skills, including musical skills, rehearsal skills and promotional/organisational skills. The popular musicians, in contrast, gave greatest weight to the theme of the importance of performance opportunities. The value of the influence of professional colleagues, in terms of moral support, supportive performance relationships and belonging to a community of practice, was found to be a fairly important theme amongst the accounts of all of the musicians, while the role of luck was briefly alluded to by classical and Scottish traditional musicians (as noted above, these comparisons are descriptive of these cases only).

Personality factors

As one classical undergraduate musician succinctly stated, ‘it's 50% playing and 50% the person’. Several personality characteristics were identified as being important mitigating factors in the transition into the music business; these included self-confidence, perseverance, and enjoyment of music, communication skills and high musical standards (Table 5).

Table 5 Personality factors found to ease the transition into musical careers

Bradley, a popular portfolio musician, emphasised the importance of interpersonal skills: ‘the social side of it is really important, being able to get on with people’. Seona, a Scottish traditional musician, emphasised the ability to use interpersonal skills in the context of engaging audiences and putting across musical ideas: ‘what I look for is communication, understanding and the ability to put that across’. There was a strong sense of perseverance, amongst all of the musicians, and encapsulated by Bridget (classical musician): ‘I've got to always push myself to get more ability . . . I am quite dedicated to that and quite strict with myself’. Dedication and self-discipline were sustained by a tremendous enjoyment from music-making, articulated succinctly by Maria, a classical violinist: ‘I completely love music. I still practise for the sheer pleasure of it, and I don't think I could live without music’.

Developing reserves of self-confidence was found to be important for musicians from all genres. For jazz musician Peter, self-confidence grew from an acceptance and celebration of his own individuality as a musician: ‘as I feel the need less to emulate the past masters . . . feel less of a requirement to play like other people . . . I kind of accepted who I am as a musician’.

Skills:

A full gamut of musical and organisational skills was considered to be necessary for individuals cultivating a music performance career. Although it is outside the scope of this paper to give a full account of each of these sub-themes (see Table 6), the prominent theme of versatility seemed to encapsulate the significance attached to skill development on a number of different fronts. The capacity to be musically versatile was found to be highly valued and was a potent theme in accounts from all genres. There was a sense that there was little scope for specialism in the music world, if one were to forge a viable and rewarding career:

We recorded a debut CD and we are in the process of recording a second one . . . I'm writing some choral music for the local community choir and occasionally I do a bit of instrumental tuition. I also gig . . . I'll go and play with other bands. (Jessica, jazz musician)

For some the need to sometimes be ‘jack of all trades’ threatened their musical identity – ‘I don't like the fact that we don't fit into one world or the other’ (Henry, classical/popular artist) – and caused considerable stress:

‘It did make me physically ill because it was just such a strain. I was doing everything. I wrote the music, I directed, I did everything.’ (Fred, popular musician)

Musical justification for the importance of being versatile was found in the accounts from musicians representing all of the four genres:

It's important to have a range of things, because they inform each other’ (jazz) . . . ‘Any genre of music, anything. Listen really in-depthly, analyse it . . . it can be anything classical music, pop, rock, just listen to what the instruments are doing (Scottish traditional) . . . ‘I've listened to everything from jazz to rock, to pop . . . I think it's important to get inspiration from lots of sources. I think that makes a better musician, more rounded and more open-minded’ (classical) . . . ‘It's that level of obsession about his work that he'll work in any genre . . . It's complete kind of immersion and involvement in the music’ (popular).

Table 6 Skills found to facilitate smooth transition into professional music careers

Support of professional colleagues:

The importance of belonging to a community of practice, within which musicians derived moral support and forged musical performance relationships, was prominently articulated across the genres and summarised by Bridget, a classical portfolio musician who had three main performance partners:

I am very committed to those three and I'm not very keen on doing ad hoc performances or liaisons, not because I don't want to, but because I have very high standards and I don't think you can always achieve them if the personnel is not right.

The individual role within a community of practice described by Max, a jazz portfolio musician:

In order to stay in this community, to keep playing with these people, you have to react in a certain way, you have to go with it, you have to do these things . . . so you're always adapting within that community.

Performance opportunities

Clearly, performance opportunities are the cornerstone of a musician's professional life:

The moment I can . . . start working I'll be fine, and then it's just easy from then on. Once you're in the profession you just get better and better and gain more experience. (classical, undergraduate)

Performance opportunities were seen to be crucial in determining a musical pathway, yet difficult to control or predict:

I don't know what path I'll go down. It depends on what work comes up. I can't dictate that so much. (popular, portfolio musician)

For some it was perceived to be a matter of luck:

I graduated in 2005, and by that point I was quite well-established playing. And I'd been lucky enough to do lots and lots of deputising work in different bands. (Scottish traditional, portfolio musician)

I was very lucky; this was one of the areas that I was very lucky. (classical, portfolio musician)

One undergraduate described the problems she expected to encounter upon leaving higher education: ‘I don't think its motivation; I think its more opportunities.’ This very problem was experienced by Maria, a freelance classical portfolio musician, who described some ramifications:

I think I suffered a lot because . . . I didn't get enough performance opportunities. I actually spent too much time on my own, analysing myself and my own playing in an unhealthy way.

Discussion

There can be little doubt that making the transition from student to music professional is daunting. The evidence presented here suggests that, irrespective of musical genre, newcomers to the music profession must grapple with the challenges of forging a niche within a highly competitive domain, finding considerable amounts of time to devote to continuing professional development and self-promotion and overcoming internal demons in the form of self-doubt. These findings add to MacNamara et al.'s study (2006), suggesting that the fear, frustration, financial and practical constraints associated with the early years of professional classical music careers may be experiences that are shared by musicians of all genres.

As individuals acquire increased adult responsibilities, pressures on time clearly become more acute. For musicians, lack of time to devote to practising may lie at the heart of a negative cycle of increasing self-doubt and decreasing engagement in music. Furthermore, lack of performance work often means professional musicians must undertake work in non-music jobs, feeding once again into the same cycle.

Several factors were identified which helped musicians to overcome these challenges and construct fulfilling musical careers. Intrinsic personality qualities, including communication skills, perseverance, self-confidence, enjoyment of music and high musical standards, were all found to be mitigating factors, once again elucidating the findings from MacNamara et al. (Reference MACNAMARA, HOLMES and COLLINS2006). Individuals who had strategies for enhancing self-confidence could increasingly celebrate their own musical strengths, while interpersonal communication skills were valued both in terms of networking and in terms of communicating musical ideas. Perseverance and dedication to high musical standards, underpinned by a deep enjoyment and love of music, helped to provide motivation for practice in particular, as well as the incentive to strive for musical goals.

A range of musical and organisational skills were identified as factors which ease the transition into professional music, creating the impression that an aspiring musician needs to be a ‘jack of all trades’ in order to succeed. This was difficult for some musicians who would have preferred to specialise or others who resented time spent away from their instruments. However, those who were versatile musicians fared well, creating varied portfolio careers. Furthermore, musicians from all genres concurred with the notion that an ideal musician is musically broad-minded and able to engage with music from multi-genres. These qualitative findings concurred with quantitative findings reported by Creech et al. (Reference CREECH, PAPAGEORGI, POTTER, HADDON, DUFFY, MORTON, WHYTON, DE BEZENAC, HIMONIDES and WELCH2008) relating to the overall sample of 244 musicians from which the cases reported here were drawn, whereby the majority of musicians representing all four of the focus genres considered musical expertise to involve the possession of global musical skills that could be transferred to other musical genres.

Successful transitions into the music world were found to be very much dependent on relationships with other musicians. It was important for musicians to be able to identify with and integrate within a community of practice. This was possibly particularly important for freelance musicians with few performance opportunities or others who could not typically rely on the structure of regular ensemble work to provide this sense of a musical community. A community of practice was found to be important in terms of providing a source of moral support, for exchanging ideas with like-minded people and for forging performance relationships. Performance opportunities, sometimes perceived as a matter of luck, were often found to be created through engagement with peer networks. Membership of a musical community of practice thus greatly contributed to reinforcing one's self-concept as a musician, a factor that was found by Burland & Davidson (Reference BURLAND, DAVIDSON and Davidson2004) to be significant in negotiating successful transitions.

Higher education music institutions face a tall order, taking responsibility for equipping music students for facing the challenges of the music profession and also for supporting those whose transition pathways lead to alternatives to a performance career. However, if transition is treated as a process rather than an event (Hallam & Rogers, Reference HALLAM and ROGERS2008) then factors that facilitate this process may be addressed early in the higher education experience. Institutions where many musical genres cohabit have an ideal opportunity to broaden musical awareness amongst their students, providing opportunities for multi-genre communities of practice to evolve which have the potential to privilege musical versatility. Furthermore, music curricula need to have support systems in place that foster self-confidence, interpersonal skills, perseverance as well as musical responsibility and autonomy amongst students. In this vein, the importance of mentoring is paramount. Performance students typically have a mentor in the form of their instrumental/vocal teacher, and this relationship may have profound consequences for transition into professional careers (Persson, Reference PERSSON1996). Institutions need to capitalise on the potential for positive influence from these relationships and guard against negative ramifications by investing in the professional development of those who occupy the role of instrumental/vocal teacher. In short, higher education music institutions have a responsibility to their students to do all that is possible to foster a highly developed musical self-concept, which has been found to underpin success in negotiating this critical transition (Burland & Davidson, Reference BURLAND, DAVIDSON and Davidson2004).

Conclusions

This study highlights the notion of transition as a process that offers difficult challenges, yet has the potential to be facilitated by investing in the development of musical versatility and organisational skills, nurturing specific personality characteristics, and providing the context in which a strong and enduring community of practice may evolve. The evidence presented here suggests that higher education music institutions may assist their students throughout the transition process by exploring the potential for cross-genre peer networks and prioritising the importance of mentoring and fostering a versatile musical self-image for performance students.

An important finding from this study is that musicians representing a range of diverse musical genres have much in common, sharing similar fears and obstacles throughout the transition process and benefiting in similar ways from supportive professional networks and performance opportunities. Furthermore, apart from obvious specific areas such as improvisation versus notation, the skills and personality qualities that help to smooth the transition from student to professional were not found to differ a great deal amongst the genres.

Clearly interview studies such as this one have limitations in terms of scope and sample size. It is hoped that the themes that have been identified will be tested in further research. In particular, it is hoped that the speculative discussion relating to how higher education institutions might support the transition experience will be tested empirically.