Introduction

Curriculum for music education in generalist classrooms is a complex matter. The often-allied notions of progression and development require careful consideration, and it can be the case that only limited commonality can be noticed between various forms of curriculum construction. Indeed, as Anderson (Reference ANDERSON2021, p. 723) noted, “[t]here is a lack of consensus on the nature of curriculum sequencing in music education….” Anderson’s observation reflects the case now, but this has also been the case for many years.

Progression and development

One of the reasons for this lack of consensus is that we have little by way of comparison with regard to ways in which thoughts of musical progression within a curriculum can be both nurtured and then taken further for classes of children and young people. What can be observed in the construction of many classroom curricula is that of what might be termed as being “the long reach of the graded music examination” being evidenced in a number of instances. This is possibly because in the UK at least, many music teachers will have grown up taking graded practical performance examinations on the musical instruments that they play. The graded music examinations are, perforce, a sequential and progressive way of delineating attainment at a series of fixed points. In the UK system, which is also used in many other countries worldwide, these practical examinations are known as “grades” (Holmes, Reference HOLMES, Brophy and Fautley2018) and are sequenced from grade 1 through to grade 8; this use of the terminology “grade” should not be confused with that of the USA and elsewhere where it means year group, these music examination grades are not age-related. In assessment terms, these graded practical music examinations can be seen to exhibit construct validity, to the extent that they are about playing an instrument, and so in order to pass the examination, an instrument has to be played. The musical materials used for this, in other words the pieces on the syllabus, have been carefully chosen, or, in some cases specially composed, to present a progressive developmental trajectory through the repertoire in order to demonstrate attainment at the specific points chosen (we discuss the notions of “progression” and “development” below). There is nothing whatsoever wrong with this; indeed, it is a logical way to work for instrumental music performance examinations. However, this ubiquitous model of progress and progression has become so deeply ingrained into the psyche of many music educators in the English context and where graded music examinations hold sway, that thinking and conceptualising possible alternative modalities of progression, particularly, as in the case of this paper, in the context of generalist classroom music, that oftentimes all forms of presenting musical progression tends to default to a graded music examination type thinking. In other words, it is a developmental repertoire that forms the backbone of thinking, rather than progression in terms of musical constructs, musical concepts or musical schema – hence what we referred to above as “the long reach of the graded music examination.” Indeed, here in England, where we are writing, many discussions concerning the recent governmentally initiated Model Music Curriculum (MMC) (DfE, 2021), if not the MMC itself, can be seen as being predicated on this modality, with social media statements discussing the MMC focussing on the repertoire listed in it, rather than on the progression model which it espouses.

However, as a contra-example to this way of thinking, one of the progression models that we do have in music education is the Swanwick-Tillman spiral (Swanwick & Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986). The notion of a spiral curriculum did not originate with this article, and as Boyce-Tillman (Boyce-Tillman & Anderson, Reference BOYCE-TILLMAN and ANDERSON2022, this issue) observes, the research did not begin in this fashion, but the idea of a spiral in researching and designing curriculum materials has a provenance which is worth investigating.

Spirals in music education

One of the earliest appearances concerning the notion of a spiral in curriculum thinking, and the one which is often given as the source reference for this, is to be found in work of Bruner:

I was struck by the fact that successful efforts to teach highly structured bodies of knowledge like mathematics, physical sciences, and even the field of history often took the form of a metamorphic spiral in which at some simple level a set of ideas or operations were introduced in a rather intuitive way and, once mastered in that spirit, were then revisited and reconstrued in a more formal or operational way, then being connected with other knowledge, the mastery at this stage then being carried one step higher to a new level of formal or operational rigour and to a broader level of abstraction and comprehensiveness. The end state of this process was eventual mastery of the connexity and structure of a large body of knowledge… (Bruner, Reference BRUNER1960, p. 141)

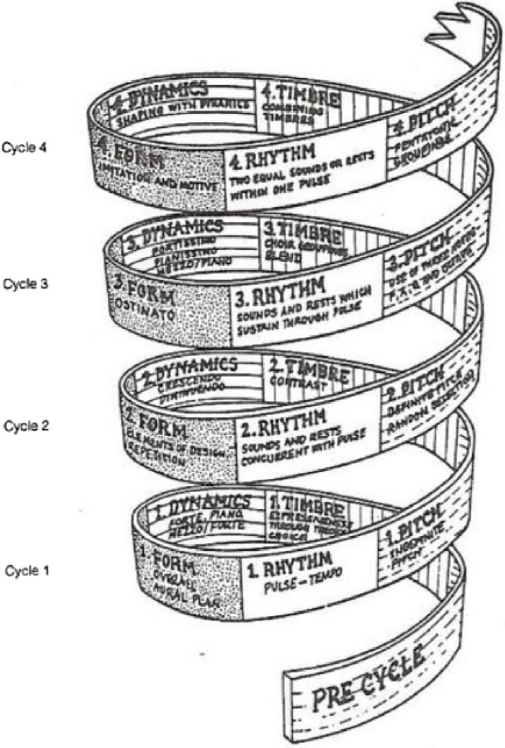

From Bruner, the idea of a spiral that involves notions of revisiting various elements is an important one, and one with which music educators will be very familiar. One of the first depictions of a spiral curriculum in music education came in 1970, with the Manhattanville Music Curriculum Project (MMCP) (Thomas, Reference THOMAS1970). The MMCP presented a visual representation of the spiral, as shown in Figure 1, where curriculum revisiting takes place across a series of cycles.

Figure 1. MMCP spiral.

The MMCP spiral and the sequence of events it delineates are described in this fashion:

1) Strategy – Teacher presents a framework for introducing a musical problem (often in the form of a question) that inspires creative thought. The problem must be well-defined, well-diversified and able to be solved creatively by all students.

2) Composing & Rehearsing – Students solve the musical problem in group composition projects by developing a musical hypothesis and testing it using aural logic. Critical thought should be used in solving the problem, and all students are encouraged to experiment.

3) Performance – After groups rehearse their compositions, a performance typically takes place to share ideas. From the experimenting process in designing their composition, the students have developed necessary musical skills needed to perform.

4) Critical Evaluation – Students may have an oral discussion after the performance to discuss and evaluate themselves. They may also record the performance for critical analysis at a later time.

5) Listening – Students listen to music for pleasure or as a resource to discover new ideas (Wikipedia, n.d.).

As can be seen from the spiral, and its associated descriptors, the MMCP spiral is itself founded on the notion of developmental compositional projects, built in turn on the idea of composing as problem-solving. It was a while before this idea was picked up again. Nevertheless, Spirals have continued to be used in music education, with more recent examples to be found in the model produced by Charanga (n.d.), as well as by the authors of this current paper (Fautley & Daubney, Reference FAUTLEY and DAUBNEY2019)

Non-linear progression

Unlike some of the spirals mentioned above, it is important to observe that the Swanwick-Tillman spiral does not, in and of itself, present itself as a solution to curriculum. The spiral is offered as a “musical development sequence” (Swanwick & Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986, p. 305). Indeed, with regard to curriculum the authors comment that it “…may have consequences for music teaching; for overall music curriculum planning…” (Swanwick & Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986, p. 305). This is important to note, as the intentionality of the spiral seems not to be that it should form the backbone of a curriculum progression model, but that it can instead help with charting musical development in terms of composing materials.

It is useful at this juncture to endeavour to distinguish between development and progression. In their article, Swanwick and Tillman cite Maccoby (Reference MACCOBY1984) to point out that development, in the sense they are using it, is a psychological construct concerned with maturation and interaction. More recently, and certainly since the article in question, the notion of progress has been defined by Ofsted, the quasi-governmental schools’ inspection body in England, as being this:

Learning has been defined in cognitive psychology as an alteration in long-term memory: “If nothing has altered in long-term memory, nothing has been learned.” [Sweller et al., Reference SWELLER, AYRES and KALYUGA2011 (p. 24)]. Progress, therefore, means knowing more (including knowing how to do more) and remembering more (Ofsted, 2019, p. 5).

One of the implications of this statement is that progress has come to have a very specific meaning in terms of education and schooling, at least in England, and that confusions of development, in other words a psychological terminology, with progression, which according to the Ofsted definition lies within the domain of learning and memory need to be reconsidered. As the Swanwick-Tillman spiral does not carry direct curricula implication within it, its application needs to be considered in ways which are appropriate across both of these domains. However, what the spiral can do for us in music education is to call into question notions of linear progression. The idea that progress can be considered only in the linear terms of a straight line has been a recurring one in assessment discourse; this is the notion of a smooth and always ascending flightpath of attainment grades. As Weeden (Reference WEEDEN, Jones and Lamber2013, p. 143) noted, “English assessment models are based on a hierarchical linear sequence of performance which implies that learning is a series of steps.” Although Weeden was writing in the context of the school subject of geography, the same progression model was employed across all National Curriculum subjects in England, and this way of viewing progress as a linear trajectory was common across all subjects. Indeed, it was not uncommon to find publications from government which showed charts of progression represented in this fashionFootnote 1 . However, the linear model is problematic:

The linear model presumes predictable and common stages of development and ignores children’s social and cultural backgrounds which so affect their perception of what music is and means to them (Spruce, Reference SPRUCE and Spruce2001, p. 20).

This presumption, outlined clearly by Spruce, is noticeably absent from notions of spiral representations of thinking. Indeed, the fact that movement through the spiral is not relentlessly unilinear is an important aspect of the way in which spiral thinking is conceived from the outset. This is not to say that progress and progression are not important in music teaching and learning, instead what is being posited is that trajectories and directionality can change with both topic and resources employed. This is an important and useful contribution for music educators.

Examples of music educator understandings of non-linearity of progression models in teaching and learning can be considered in terms of attainment, and, importantly of representations thereof in assessment. Most music educators would be entirely happy to think that in a sequence of three classroom music projects, the first on, say minimalism, followed by one on the 12-bar blues, and then by a project on English folk songs, would not automatically result in every pupil attaining at a higher level in the work on folk songs than they had on minimalism. Instead, although teachers would be more likely to expect the graph of attainment to be broadly upwards, as understandings, depth of knowledge and skills increased, but that the individual’s attainment grades within each unit of work could be very different. What this means here is that although increasing musical understanding is likely to be a goal of generalist classroom teaching (Rogers, Reference ROGERS2020), the pathway towards this is likely to involve peaks and troughs, and that this is a normal and to be expected thing.

Research in music education

Turning now to the Swanwick-Tillman spiral model itself, one aspect that stands out is the series of iterations that it went through over time, as ideas were considered, reflected upon and developed. This appears to be relatively unusual in music education research, where development and replication are not necessarily common attributes, maybe because of the relatively limited size of the domain. Whatever researchers and educators think of the model itself, and the applicability of it beyond the initial research parameters, the interest in, citation of, and critique concerning this spiral model, have without doubt provoked thought and discussion from multiple fields of study related to music education, as well as influencing developmental and curricular models (e.g. Booth, Reference BOOTH2022, this issue). Indeed, it is not a weakness of the original research to develop, progress and move on in this way and to read the author’s own reflections on this process (Boyce-Tillman & Anderson, Reference BOYCE-TILLMAN and ANDERSON2022, this issue) sparks afresh new possibilities for thought and further development, now with the advantage of 35 additional years of thinking about music and education to look back over and draw upon. Such an iterative reflective and reflexive process is both commonplace and usual in other fields, medical research being a prime example, and such an approach would arguably benefit music education too. In the various fields of music itself, just as music is often evolving – we only need to look at the multiple cover versions of different songs, and the way that live versions of music are often purposefully different to those found on recordings – and as Berio’s Sequenza shows the evolutionary developmental alterations of music over time from the perspective of a composer – there is a parallel here with the iterations of the Swanwick-Tillman spiral over time.

What is harder to ascertain, certainly in the context of music education in England, is the place of the Swanwick-Tillman article in current developmental curriculum thinking in music education. This is in itself not unusual in the incessant searching for the new, and the deliberate downplaying of the old, which characterises policy-making in England, and in a number of other jurisdictions too:

…even if one forgets or chooses to ignore the past, it will come back to bite you. Yet, with its incessant focus on innovation and modernisation, contemporary policy discourse often implies that the past is either irrelevant or only a negative, restraining influence. Either way, the past should play little part in progressive policymaking, which should be focused on the latest bright new dawn (Pollitt, Reference POLLITT2008, p. 1).

This view, which is so pervasive in English education that the policy imperatives of always privileging the new, has also come to affect research across the broader arena of social sciences in general, and thence to educational research, and finally to music education research in particular. Allied to this downplaying of the past is the relatively short amount of time that pre-service teacher education in England affords to programmes. The standard length of such programmes is one academic year, with a governmental requirement that at least 120 days of such courses must be spent on placements in schools, also known as practicums. It is clear to see that with such a requirement, there is precious little time left for delving into what might be considered key texts in music education, although the fact that many pre-service teacher education programmes manage to do just this is a tribute to the people who run such courses. But the end result is that in England, classroom music teachers then need to rely once they are in positions in schools on the provision of continuing professional development (CPD) courses, attendance at which is non-statutory, and which are themselves not subject to regulation or oversight, and can involve paid-for attendance. It is against this backdrop that the many music teachers who are aware of the Swanwick-Tillman spiral, and associated music education research, needs to be placed.

Influence

So how can we assess the influence of the Swanwick-Tillman spiral on thinking, curriculum and teaching and learning more generally in music education in England in the elapsed time since its publication? We know that for many years, the article was the most cited from the BJME, according to metrics on the journal homepage (Cambridge.org, 2021) with 130 citations at the time of writing. However, an alternative widely available freeware bibliometrics site (google scholar, n.d.) places the number of citations of the article at 686, again at the time of writing. Whatever the exact number of citations, we can be sure that the spiral has had an effect upon thinking about spiral learning in music education and the development of composing as a context for teaching and learning in musical development in schools. School teachers tend not to cite their sources in preparing curricula for use in their own schools, so we may never know the true extent of this.

Curriculum music in England’s schools currently finds itself in an increasingly difficult place, for a number of reasons including, but not limited to, a focus on “core” subjects at the expense of the arts, accountability measures such as the English Baccalaureate (EBacc) which excludes the arts, and a high-stakes inspection regime that, until recently, has focussed on core subjects rather than music and the arts. The increasing academisation programme, in other words the removal of schools from central direction (Rayner et al., Reference RAYNER, COURTNEY and GUNTER2018; Gorard, Reference GORARD2009), has given schools the freedom to ignore the National Curriculum. Considerable research evidence exploring and documenting the demise and struggle of curriculum music education can be found in multiple reports (e.g. Daubney, Spruce & Annetts, Reference DAUBNEY, SPRUCE and ANNETTS2019; Savage & Barnard, Reference SAVAGE and BARNARD2019; Bath et al., Reference BATH, DAUBNEY, MACKRILL and SPRUCE2020). In children’s early lives, musical learning and engagement contributes significantly to their interaction and engagement with their world and influences their learning. The current English National Curriculum for music (DfE, 2013), whilst short in content, overtly encourages creativity and musical exploration through the embodiment of music; the integration of musical process such as improvising, composing, performing, listening and responding to music through the use of instruments and voices invites young people aged 5–14 to practically and intellectually explore a wide range of musical influences and develop their own skills, knowledge and identities in and through music. Nevertheless, the usefulness of such a short document can be viewed in multiple ways, and whilst the freedom that it offers can open up a world of exciting and progressive musical teaching for music teachers (Daubney, Reference DAUBNEY2017), it could potentially be the case that some may find the lack of detail limiting. Nevertheless, even within the brevity of the current National Curriculum for music, there is implied musical development. For example, it provides the expectation that pupils create and perform music with “increasing… confidence and control… accuracy, fluency, control and expression… aural memory…awareness [and]…discrimination” (DfE, 2013).

Learning in the Model Music Curriculum

However, as mentioned above, in recent times the government in England have published a significant document of non-statutory guidance in an endeavour to put some flesh on the bones of the National Curriculum, this being the “Model Music Curriculum” (DfE, 2021). Although wide-ranging in scope, this document does not show its thinking as to how the various aspects of musical learning it describes have been arrived at. Within this document, it is difficult to see any identifiable influence of developmental models of music education permeating the areas of learning, despite the significant amount of research in this area. The press release to the Model Music Curriculum gives an indication of the focus of the learning within this model curriculum, indicating what might be considered as a passive engagement with music (our highlighting and underlining):

More young people will have the opportunity to listen to and learn about music through the ages, from Mozart and Bach to The Beatles and Whitney Houston, as part of a new plan for high-quality music lessons in every school.

As part of the curriculum, pupils will learn about the great composers of the world and develop their knowledge and skills in reading and writing music. They will be taught about a range of genres and styles covering historically-important composers such as Vivaldi and Scott Joplin, world renowned pieces like Puccini’s Nessun Dorma, and be introduced to instruments and singing from Year 1.

In this article, we are concerned with the Swanwick-Tillman spiral, and its impact on musical thinking, so in relation to children’s composing, the Model Music Curriculum outlines tasks for every year group, which some might consider as being limiting and controlling, and when these are allied to what seems to be a central purpose of the MMC, that of children developing notation skills, then this approach bears very little relationship to the playful, imitative, initial approaches taken by children in Tillman’s research, and developed and outlined within the model. Nor, indeed, does this seem to build on the stages outlined, described and defined within Piaget’s stage-development model (Piaget, Reference PIAGET1952) which underpinned early iterations of the spiral. Having said this, it is however, only fair to point out that it is difficult, post hoc, to extrapolate retrospectively from the published MMC document in order to analyse the thinking that informed its construction. In early consultation meetings on the development of this Model Music Curriculum, concern was raised that the document should “show its workings” and that it should draw appropriately and extensively on music education research (Daubney, Reference DAUBNEY2021). Unfortunately, this did not come to pass; instead, an edited list of documents and evidence that the panel were sent is listed with the phrase “The following publications were recommended for reference” (DfE, 2021, p. 100), without any indication within this model curriculum whether these were considered. It may, of course, be the case that political interference in the production, construction and publication of the MMC document were such that the evidenced thinking discussed here were submerged beneath political imperatives dictated by government ministers. After all, as Espeland notes:

Knowledge is the basis for power and power produces knowledge. Curricular reforms are… examples of a process where there is a close connection between the production of knowledge and power (Espeland, Reference ESPELAND1999, p. 177).

And we know that the government minister of the time in charge of the production of the MMC, Nick Gibb, stated that his “… aim is to make sure that every child is taught to read and write musical notation and has been introduced to the musical giants of the past…” (Gibb, Reference GIBB2021). This helps explain the centrality of musical notation to the MMC, although, as has been stated above, if this is the central purpose of the MMC, this is not explained. Indeed, not only is the thinking behind the construction of MMC not explained, neither is the notion of what has informed its views of what counts as musical learning, as the ISM (Incorporated Society of Musicians) noted:

“There is no explicit explanation of overarching musical understanding. This has been at the heart of nearly all earlier national developments for curriculum music” (ISM, 2021)

All of which is a long way from the thinking which lies behind the Swanwick-Tillman spiral, where the intentionality of the authors and the genesis and antecedents of the spiral are clearly laid out in the accompanying article.

What all this means is of concern to the future direction of music education thinking in England and possibly elsewhere too. The downplaying of the past, the political imperatives of making a mark on schooling and the political will to impose certain views on thinking, and thence on teaching and learning, whichever end of the political spectrum they come from, are of concern to all who work in music education. It is to be hoped that significant contributions to the domain from the past, as the Swanwick-Tillman spiral article can clearly be seen to be, should be something which are drawn upon, and used as a basis for progression – as Isaac Newton said, by “…standing on the shoulders of Giants.” We do not need to continually discard the old in favour of the new, to throw away when we can use, to not introduce the thinking of previous times. As the National Curriculum for England asks teachers to introduce children and young people to the “…works of the great composers and musicians” (DfE, 2013) then it seems logical to extend this consideration to classroom music teachers too.

Concluding thoughts

Music education is in a state of being a constantly evolving field and domain. The changing styles, genres and musical types are a constant, as is the development in scholarship of performing practices concerning the musical styles of different periods of musical history, alongside the constant new music being composed, performed and brought into being across all styles, types and genres. Music education should be as much about preparing children and young people for participation in future musical activity, as well as in looking at, listening to and participating in the reproduction of music of the past. Composing music is not a static enterprise either, and the education of the next generation of young creatives needs to be an important part of what is done in schools. But not only for this purpose, learning to compose as a part of generalist music education gives insights into composerly thinking and enables all children and young people to engage with music directly.

Thinking of curriculum, although Swanwick and Tillman did not suggest the production of a curriculum for music education from their work, they did, however, have something to say on this matter:

What is being suggested here is a strategy for curriculum development. We start from a collection of musical materials; then, no matter how tightly or loosely we organise the learning process, we shall be looking for the next question to ask. Asking the next question depends on having an idea as to what possible developments might be “round the corner.” In our spiral, so to speak, we have many corners (Swanwick & Tillman, Reference SWANWICK and TILLMAN1986, p. 337).

In order to try and work towards this end, it would seem to be helpful that music educators of whatever formation would benefit from not only knowing what they are teaching, and how they might go about teaching it, but also, and crucially, why they are doing this, or, in Swanwick and Tillman’s phrase “asking the next question” (ibid). To this end, we need more music education research articles like the Swanwick-Tillman piece, as it is in this area that future teacher development occurs. As Stenhouse observed back in Reference STENHOUSE1975, there can be “[n]o curriculum development without teacher development” (Stenhouse, Reference STENHOUSE1975, p. 142). That is a mantra which politicians and curriculum designers of the future would do well to heed.