Introduction

Many adults take up or return to a musical instrument in later life. The richness of their musical experience (see Crafts et al., Reference CRAFTS, CAVICCHI and KEIL1993) places them in a very different position from children and young people when they engage with instrumental learning. However, there is little research which explores their musical enculturation, the process of learning the traditional content of a musical culture and assimilating its practices and values. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that musical life experience issues are not often explored during instrumental teaching and learning sessions.

Arguing persuasively, Hendry and Kloep (Reference HENDRY and KLOEP2002) suggest that personal growth and identity development over the lifespan takes place in a series of developmental shifts stimulated by life challenges, whether they be task, crisis, stimulus or loss. These may arise from predictable events which happen to everyone like starting and leaving school, and from unpredictable events for individuals such as moving house, serious illness, divorce, and retirement. The extent to which musical participation and learning and concomitant musical identity construction might resonate with such shifts and responses to life in addition to creating its own challenges is worth considering.

This article discusses the lifelong musical experiences and concomitant musical identity construction that six of 21 keyboard players with an average age of 67 brought to their formal music learning as mature adults. Although there are dangers associated with retrospective studies in terms of bias, in that what people choose to select and omit from their (musical) life histories will depend up to a point on the situation in which they find themselves when reflecting on their lives (Harré & Langenhove, Reference HARRÉ, LANGENHOVE, Harré and Langenhove1999), it was not possible to complete longitudinal observational and interview studies of these respondents as an alternative way of exploring their lifelong musical participation and learning.

The use of ‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ as a tool for semi-structured interviewing

‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ were used as a research tool to facilitate semi-structured interviewing in emergent case study research. Interviews were held in the north of England from autumn 2004 at regular intervals for two and a half years when individuals interested in taking part in the study became available. In the absence of a model of this research tool for use with adult music learners, ‘River of Musical Experience’ diagrams similar to those designed for use with children and music teacher training students (Burnard, Reference BURNARD and Bartel2004a, Reference BURNARD2004b) proved useful.

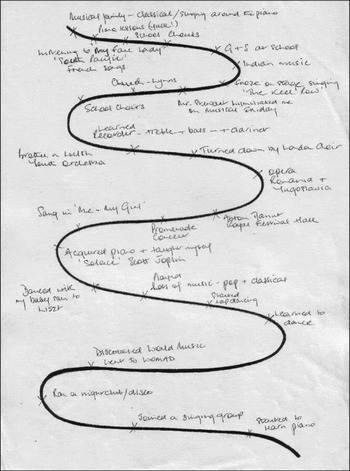

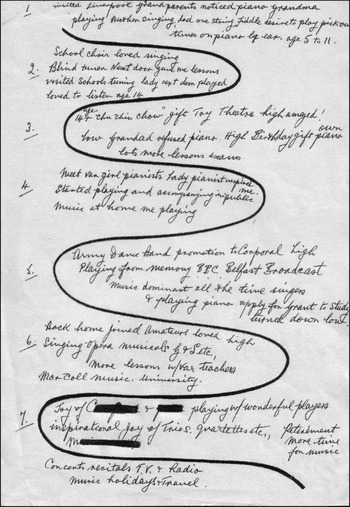

The participants received written instructions to reflect on the critical incidents or musical events which impacted on their musical lives both positively and negatively up to the point of data collection, and to mark them on the bends of a diagram of a winding river. The instructions emphasised that writing about any form of engagement with music, whether formal or informal, was useful and interesting. This reduced the likelihood of individuals trying to impress or feeling self conscious (Cross & Markus, Reference CROSS and MARKUS1991), and made it possible to explore the wide range of music experience they had to offer. Everyone was supplied with a diagram to complete before they were interviewed, and conversation around it was gently guided with open-ended prompts (see Appendix). As their researcher, I completed my own ‘River of Musical Experience’ before interviewing the respondents. This helped me to understand the reflection and self examination process they would need to undertake.

Whilst three of the 21 participants preferred to write an outline on their own paper and two others needed verbal reassurances to supplement the written instructions, the use of this research tool to facilitate semi-structured interviewing proved to be very effective. This was because the respondents had thought about their musical experiences in advance in a highly focused manner and could use their own written records as a prompt during their interviews. This helped to create a suitably non-threatening environment (Denicolo & Pope, Reference DENICOLO, POPE, Day, Pope and Denicolo1990) where they acted as co-researchers, and the barriers between them as interviewees and myself as interviewer were lowered. Conversations thus flowed freely and spontaneously, moving away from musical life as illustrated on the diagrams to current learning and back again. The diagrams also triggered memories of incidents that had not been recorded.

When appraising their use of ‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ for reflection, the respondents offered a wide range of comments, sometimes more than one. These were as follows: (very) interesting (5); enjoyable (4); good to have helped me in my research (2); a reminder of things forgotten (2); a chance to note patterns in life (1); a chance to note ‘the happy times in the past’ (1); reaffirming (1); confidence-building (1); ‘good to introspect’ (1); ‘makes you realise how difficult it is to put things into words’ (1); ‘an achievement because of my [poor] spelling’ (1); ‘depressing to fill it in because I was going over things I need to get away from’ (1); ‘a little self indulgent to reflect on myself’ (1) ‘almost autobiographical’ (1); ‘fascinating. I hadn't realised what a strong thread music has had in my life’ (1); and ‘an intellectual exercise’ (1).

In this way, I was helped to understand the uniquely complex and highly personal context for learning that each respondent had experienced. I could make useful connections between the events noted on the diagrams and discussed at interview, and how the respondents understood and approached their current learning as mature adults (see Pope & Denicolo, Reference POPE and DENICOLO1993). Very shortly after their interviews, the respondents evaluated my interpretation of what they had said, and their comments were later taken into account when writing this article. These member checks ensured an accurate representation of the participants’ views which increased the trustworthiness of the study (Crabtree & Miller, Reference CRABTREE and MILLER1999; Cresswell, Reference CRESSWELL2003) as well as extending the topics for discussion in future interviews.

Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA)

The current study is an example of hermeneutic enquiry (Palmer, Reference PALMER1969) taken from the theoretical perspective of Interpretivism (see Burnard, Reference BURNARD2006) in which the uniqueness of shared meanings and common practice is explored and the interpretation of the researcher acknowledged. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) as evolved by Jonathan Smith was adopted for use within this framework. IPA is a two-stage interpretation process or double hermeneutic: that of participant(s) trying to make sense of their world and researcher(s) trying to make sense of what they say, in which the first stage is empathetic and the second stage critically questioning (Smith & Osborn, Reference SMITH, OSBORN and Smith2003). The aim of IPA is to uncover meaning that is not transparently available, and it stresses the importance of clearly differentiating between what is said by the respondents and how it is interpreted by the researcher (Smith, Reference SMITH, Smith, Harré and Van Langenhove1995). IPA is idiographic in that it requires the analyst to make a detailed examination of one case study before moving onto others in a process of constant comparison. IPA is flexible in that it allows unanticipated topics or themes to emerge, and acknowledges misfits and contradictions. Research results and discussions can also be presented in different ways to reflect different levels of analysis. Finally, IPA relates to other research by situating the findings in relation to it (Smith, Reference SMITH2004). Illustrations of these uses of IPA can be found in this article. For a step-by-step guide to using IPA, see Smith (Reference SMITH, Smith, Harré and Van Langenhove1995) and Smith and Osborn (Reference SMITH, OSBORN and Smith2003). For further guidance and discussion about its use in qualitative research, see Smith (Reference SMITH2004); and for a critical evaluation of IPA, see Brocki and Wearden (Reference BROCKI and WEARDEN2006).

What follows is an exploration of the wide range of past musical influences, incidents and experiential learning with which six respondents constructed their musical identity as mature adult learners. Mature musical identity can be understood in terms of musical self derived from personal musical meaning and motivation accrued from a lifetime of musical experience including current musical participation and learning, and also as social construction through shared identification with musical groups and genres. See MacDonald et al. (Reference MACDONALD, HARGREAVES, MIELL, Hallam, Cross and Thaut2009) for further discussion of musical identity. This article aims to elucidate musical motivation and identity in mature adults learning for self-fulfilment by presenting examples of individual lived experience of music and concomitant musical identity construction over the life-span (see Van Manen, Reference VAN MANEN1997) whilst exploring similarities and differences between individuals and others situated in the same music learning world. Discussion draws on statements emerging from reflection at interview as well as those written on the ‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ diagrams. To preserve anonymity, those names that would reveal the respondents’ identity have been changed in the narrative, and in Figs 1–6 they have been blacked out and/or replaced with the first letter only. The artefact transcriptions in Figs 1–6 include extra punctuation and explanatory material in brackets where clarification was necessary. This article will conclude with implications for music education.

Fig. 1 Jane's musical river. Transcription: Went for my 1st singing lesson would be aged between 9 + 10 yrs [years] old. I can remember singing Early one Morning. Remember taking part in the F. musical festival and also B. music festival aged 10–11 yrs [years] old. Our headmistress Miss C. was an inspiration. I was in the school choir and before any special event, she used to tell us to remember the 3 Cs = keeping COOL, CALM + COLLECTED. Took part in a talent contest while on holiday at M.T. holiday camp. I sang Tommy Steel's Singin the Blues! Of course I didn't win but it was a great experience I would be about 16. 1955–1959 I was in the church choir for about 3–4 yrs [years]. Also rang hand bells for a short while. My son bought me a keyboard Christmas 1999. I started going to A. College for lessons. Played for about 4 years. Really enjoyed it. Always wanted a keyboard and a piano! I finally acquired a piano and am now playing piano at A. College. It's a challenge.

Fig. 2 James' musical river. Transcription: School music lessons – instruments of the orchestra Piano lessons. Sunday pm and boring Radio. Jack Jackson. Late Saturday evening Les Paul! Record ‘Blues in Thirds’ (Earl Hines, piano). Gerry Mulligan ~ W. Coast jazz. Hi Fi & ‘classical’ music. Discovered big bands. Miles Davis ‘Miles ahead’. Singers and songs Singers – piano backing. (Andre Previn, Ellis Larkin) William Bolcome + Joshua Rifkin – recordings of ragtime music. Stacey Kent – Live in Manhattan club. Les Paul – Live in New York Club. 1992 – Retirement plans – jewellery, piano. 2002 – Bought Keyboard. College Keyboard course.

Fig. 3 Carla's musical river. Transcription: Musical family – classical/singing around the piano. Piano lessons (yuck!). School Choirs. Listening to ‘My Fair Lady’. ‘South Pacific’. French songs. G&S at school. Indian music. Froze on stage singing ‘The keel Row’. Mr S. humiliated me on Musical Friday. Church – hymns. School choirs. Learned recorder – treble + bass – + clarinet. Brother in Welsh Youth Orchestra. Turned down by London choir. Opera Romania + Yugoslavia. Anton Manut Royal Festival Hall. Promenade Concert. Sang in ‘Me and my Girl’. Acquired piano + taught myself ‘Solace’ [by] Scott Joplin. Danced with my baby to Liszt. Played lots of music – pop + classical. Started tap dancing. Learned how to dance. Discovered World Music. Went to WOMAD. Ran a nightclub/disco. Joined a singing group. Started to learn piano.

Fig. 4 Tom's musical river. Transcription: 1. Visited L. grandparents noticed piano, grandma playing, mother singing, dad one string fiddle. Desire to play pick out tunes on piano by ear. Age 5–11. 2. School choir loved singing. Blind tuner next door gave me lessons. Visited Schools tuning [pianos]. Lady next door played, loved to listen age 14. 3. Age 14+ ‘Chu Chin Chow’ gift toy theatre – High. Amazed! Low – Grandad refused [to give] piano. High – Birthday gift own piano. Lots more lessons. Exams. Meet var[ious] girl pianists. Lady pianist inspired me. Started playing and accompanying in public. Music at home me playing. 5. Army dance band promotion to Corporal – High. Playing from memory BBC Belfast broadcast. Music dominant all the time. Singers and playing piano. Apply for grant to study turned down – Low. 6. Back home joined amateurs – High. Loved singing opera musicals G&S etc. More lessons with various teachers M. Coll[ege of] Music. University. 7. Joy of C. [summer school] & Brian playing with wonderful players [and] inspirational joy of trios, quartets etc. M. [music club]. Retirement. More time for music. Concert recitals TV + Radio. Music holidays + travel.

Fig. 5 Paula's musical river. Transcription: Father keen lover of classical music – vast record collection. Played piano from 9–15 – a great source of pleasure and solace. Passed Grade 5. Sang in school choir. Music seemed to slip out of my life as other interests took over (age 15–30) although I remained a keen listener. Age 30+ Through practice of yoga rediscovered delight in the voice through mantra and singing bhajans [sacred songs]. Also as time rich (being unemployed for a while) took up saxophone (reached about Grade 4) clarinet (again about Grade 4) and flute (Grade 2). Sold my saxophone – too unwieldy to carry around without a car. Developed interest in voice work through Dances of Universal Peace – which I eventually trained in – age 45 approximately. Started teaching classes involving Peace dance with special needs students and singing groups with physically handicapped adults. Aged 49. Lost my voice for 3.5 weeks when decided to finally leave my ex-husband! M.E. and voice loss made singing very difficult for years – very depressing. Took up piano again – have now reached Grade 5 – enjoying piano jazz. Am singing again in a choir. Have started music theory study.

Fig. 6 Alan's musical river. Transcription: First piano lesson. Didn't like teacher! – 1954. Greater awareness of music at Grammar [selective secondary] school – 1957. Opted for Music ‘0’ level [examination for 16 year-olds] – 1959. Hooked on classical music. Achieved 5th Form [year 11] Music Prize. Amazed – 1962. Inspired by soloist I heard in BSO [orchestra] concerts. Increased concert going [and] broadened knowledge – 1962–64. Disappointed at not getting University place I wanted, but obtained place at B. School of Music. Decided I would not make a career in music and that performing was out – 1966. Joined G&S Society in K. – 1975. Not my scene! 1985 – complete change to folk scene and became a Morris Dancer until 1994. Really enjoyed it, but needed something more musically demanding. Joined George's advanced class at A. College – 2005. Played in M. [music club] concert and in masterclass.

Findings and discussion

Participants

The six participants, three novices and three relatively experienced instrumentalists, were chosen for discussion in this article because their ‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ clearly show contrasting positions possible in relation to lifelong engagement with music and motivation for learning a keyboard instrument formally as an adult for self-fulfilment. Three of them were retired, one was unable to work for health reasons, and two were working part-time.

Amongst the novices learning in college workshops run by the researcher, 63-year-old Jane (see Fig. 1) was someone who had not had the opportunity to learn the piano as a child. Once she left school there was no time for music until her late 50s, when after learning the electronic keyboard, she finally took up the piano which she had always wanted to learn. 73-year-old novice electronic keyboard player and pianist James (see Fig. 2) had learned the piano as a child, but found it boring. However, he became a keen jazz listener from his teens onwards, and returned to active musical participation in retirement. Whilst 58-year-old pianist and singer Carla (see Fig. 3) only played the piano intermittently once she had stopped taking lessons as a child, other musical participation had been important to her before she made a fresh start on the piano in her late 50s.

Amongst the experienced players who were taught by other tutors, 57-year-old pianist and singer Paula used music, though not the piano, to connect with her interests and personal beliefs and to create a work identity (see Fig. 5). 80-year-old pianist Tom used the piano from his teens onwards as an enjoyable means of making contact with others (see Fig. 4). In contrast, 60-year-old pianist Alan's musical life (see Fig. 6), though varied, gave him little musical satisfaction until he returned to the piano in early retirement, taking lessons for the first time in 40 years.

The following thematic categories emerged from analysis of the six ‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ and related discussion in the interviews: family associations; reconnecting with music in youth: a basis for music as an adult; music and the piano as social enrichment; music and disappointment; and music as empowerment. As befits the complexity of the participants’ musical experiences, these categories overlap, and references are made to other sections in the article where appropriate.

Family associations

Interest in music within the family contributed significantly to the respondents’ motivation to engage in active musical participation and learning, and to their identification with music at all stages in their lives. Whilst James and Tom's wives actively supported their musical involvement, all except James also had memories of parents or grandparents who enjoyed music. These memories varied. Carla and Jane recollected a lot of family music making, with ‘singing around the piano’, as did Tom whose father played a one-stringed fiddle for the family as well. However, in Paula's case, music was not shared with the rest of the family. Instead, her father listened to music on his own for many hours in the ‘no-go area’ of their living room. This made an indelible impression on her:

He would just get totally caught up in it, but then I can see that myself, you know and I've seen that in different times in my life where I've got so totally drawn into music it's like, it's very seductive, it has that charm, or it can have, certainly. So that I think that's kind of affected me all my life, sort of that awareness of its charm.

When she was nine she was sent to boarding school for six years. Unhappy there, she found solace in playing the piano on her own, and music later played an important part in her personal development as an adult (see Fig. 5 and discussion later in this article).

Reconnecting with music in youth: a basis for music as an adult

The rivers of all six participants show that they all had some musical experiences which they enjoyed when they were young. This enabled them to construct a positive youthful musical identity which predictably was the foundation of their musical interest as adults (also see Gembris, Reference GEMBRIS, Daubney, Longhi, Lamont and Hargreaves2008; Pitts Reference PITTS2009). Nevertheless, not all of them had positive experiences with a keyboard instrument. Unlike Tom and Paula, and Alan with his second teacher, Carla's piano lessons were always very difficult for her:

I was sent on my own to the piano teacher's house . . . It must have been quite a long walk for a six year old . . . I had to go over this bridge and there was something sticking out of the river, and I always thought it was a dead cow, the leg of a dead cow . . . I didn't want to go, didn't feel welcomed, there was nothing about it that was positive, got to go and do it and come home, ‘Go and practise the piano, go and practise the piano till next week go to the piano lesson’ . . . When I was eight, as soon as we got to India, sweltering temperatures . . . walking down the road in the darkness to the piano teacher's house, and another experience of never being relaxed. It was just awful.

Her negative experiences with the piano, an instrument which she declared that she had wanted to have as something to play with, continued when her head teacher made sarcastic comments about how she presented herself to the school on ‘Musical Friday’. But her other musical participation and learning in India profoundly affected her sense of musical self to the good, as suggested by the ecstatic tone of the following:

And on Easter morning we would have a sunrise service, and so we all got out of bed at about 4:30 in the morning, got a chair each, trooped down the mountainside, quite a way, probably about a mile or so, to this little plateau in the school grounds, sat our chairs down and sang all these Easter hymns as the sun came up. And it was, [sings] ‘Up from the grave he rose, he rose, with the mighty!’ You know, it was just the most exciting, gorgeous, glorious. To me it was almost pagan. It was like, ‘God, this is, absolutely-’. All these little school kids!

Peak musical experiences like this could well have outweighed Carla's negative musical experiences on the piano and formed the basis of her lifelong interest in music shown in her river. She returned to the piano as an adult when her friend enrolled her without her knowledge. She had wanted to take up the piano again for years, explaining that, ‘I know there was a pianist there, I just know. I always knew, she just wasn't allowed to emerge’. Clearly, she still identified with the instrument despite her negative experiences with it in the past. Her fresh start with the piano in her 50s was ‘the polar opposite’ of what she had known as a child. Now she could ‘play it how you feel. Do your own thing . . . it's entirely up to you’. Through choosing what she learned and how to do so as an adult so she could rework her past negative experiences with the instrument.

James had found his piano lessons boring as an eight-year-old, but, like Carla, he experienced music extremely positively in other ways as a youngster. A strong initial source of musical inspiration was a series of lessons on the instruments of the orchestra given by a teacher who ‘could make a telephone directory interesting’. When he was about 13 or 14 he further developed his interest in music when ‘a little crowd of us at school had this craze of playing harmonicas, and getting quite serious, playing at playtimes and things’ (omitted by mistake from his ‘River of Musical Experience', see Fig. 2). A couple of years later he discovered jazz which became a life-long musical interest, ‘a significant part of all of my life’.

The attraction of jazz for James, as in the recording of Blues in Thirds by pianist Earl Hines (see Fig. 2), was ‘being able to hear things clearly . . . it's very much about sound . . . what one person makes one instrument sound like’. He valued clarity, individuality and agency in performance which coloured his expectations of a keyboard instrument when he returned to one as a mature adult. He found his workshop class ‘incredibly open-ended, no preconceived ideas about what sort of music it's going to be or anything else’. He felt able to treat his electronic keyboard there like a piano, producing every sound himself rather than using the automatic sound production available on the instrument to help him. When the keyboard workshop closed, James, unlike his peers, joined a new piano workshop at the same college.

Joining a keyboard workshop to learn the instrument that he had found boring as a child marked the beginning of James' adult musical identity shift from music listener to performer. During the next few years he also taught himself the Appalachian Dulcimer (a single-stringed guitar-like instrument played horizontally across the knees) and played it for fun with his friends in the local folk club, as he had once played the harmonica with his friends in the school playground. It appears that by reconnecting with the schoolboy who found his school lessons about musical instruments interesting, who enjoyed playing the harmonica with his friends, and who loved to listen to jazz, rather than with the musical child who had found his piano lessons boring, James was able to realise a possible musical self as performer in public and reconstruct himself as a mature adult musician. This musical transition seemed to mirror the life shift which he experienced after his ‘fall down on the floor job’ heart attack when he realised that ‘tomorrow isn't there forever’. Six years after completing his ‘River of Musical Experience’, he was still using his piano skills to work out tunes to play on the dulcimer which he practised every day for his regular public performances in the folk group.

Music and the piano as social enrichment

James used music during his adult life to connect with others through a shared interest in listening to jazz before returning to active participation with others in the workshop and in the folk group. Carla and Paula (discussed later in this article in connection with music and empowerment) sang and played and went to concerts with other people. Tom, however, stood out as someone who used the piano itself, usually a solo instrument, for social cohesion throughout his life (see Fig. 4). During his teens, a strong musical self-concept emerging, he played the piano at family parties:

Oh Tom'll play, everybody knew I did it, and I used to have to sit down and play and entertain them, or we'd have a good sing and get together, and certain people would sing solos, you know, and that was my first try at accompaniment really.

When he was enlisted in the army in his late teens, he joined the unit dance band as a keen amateur musician, was promoted to Corporal, and learned to play jazz piano from a trumpeter. This ‘stuck with me ever since. I've never forgotten it’. Tom marked this period as a ‘high’ on his river. This was counterbalanced by a ‘low’ when he returned to civilian life and failed to get a grant for musical study. He described this as being ‘a slap in the face’. Nevertheless, Tom's musical self-esteem remained high with ‘music dominant all the time’ during his working life and retirement. He was strongly encouraged by his wife in his musical activities. ‘We are as one’ he said of her. As well as singing in the local Gilbert and Sullivan society, taking piano lessons intermittently, and participating in piano master classes (see Taylor, Reference TAYLOR2010), he also accompanied ‘a group of lady singers’ regularly at the local hospice, and attended the piano accompanists’ course at summer school. Here his tutor Brian,

suggested I took myself in hand, you know this is the new Tom . . . And I got landed with, I think it was a Brahms song which I didn't know, and I sight-read it.

Musically reconstructed as ‘the new Tom’, he found himself willing and able to take on new challenges. Music appeared to be a source of personal growth, self-confidence, joy and optimism for him, strongly associated as it was with the individuals and groups with whom he shared it.

Music and disappointment

Tom retained his musical optimism despite failing to achieve his ambition of studying music at college. Carla regarded her musical life as one of opportunity (see next section) despite failing to get into a choir counter to expectations as well as having experienced the piano negatively as a child. However, experienced pianist Alan regarded his musical life differently. The bareness of his river, recounting things he ‘wanted to get away from’, depicts a musical life he described as having ‘a lack of overall understanding or satisfaction that I might have wished for’ (see Fig. 6).

When he was 16, he won the 5th form (Year 11) school music prize, Tovey's ‘Essays in Musical Analysis’, to his amazement, and kept it all his life. But he subsequently failed to get into university to study music, and his disappointment was a clear threat to his musical self esteem. Later, when he was at music college, he was expected to rethink his piano technique and catch up with his peers. However, he did not meet that challenge. Instead, he decided to leave, having been unable to construct a satisfactory musical performer identity as a student. He rationalised that he had been very shy as a student and that he could not develop musically with the piano because it was too solitary an instrument: ‘I didn't have an outlet for it . . . a network in which I could play’. He did not want to teach, and he chose not to pursue music as a career.

Instead, he experimented with temporary musical identities associated with different music worlds at times of transition and change in his life. When he moved house, he joined a local Gilbert and Sullivan society for a few months. Some time later, when his first marriage broke up, he joined a Morris dancing group at a friend's suggestion, in which he also played the accordion (this instrument was not marked on his river, Fig. 6). But he did not identify strongly with those groups. It was not until he retired and returned to piano tuition with others in a piano workshop and also joined a local music club where he could perform and take part in master-classes (see Taylor, Reference TAYLOR2010) that he was able to fulfil himself musically in the company of his new musical friends. At the age of 60, he felt that,

I'm now at a point where I'm getting from my piano playing the most satisfaction I've ever got from it in the last eighteen months or so . . . It's so strong at the moment I've got to go and do it.

His impassioned tone seems to illustrate the intensity of his musical need. Indeed, Alan also said of his musical life that, ‘I keep bouncing back and wanting to persevere with it’. This suggests that he saw himself as someone musically strong who was determined and able to keep his musical life going despite his setbacks. It is surprising, though, that whilst Alan had collected a vast number of classical music records over the years, some of which he talked about as being a reference point for his own playing, his river diagram shows no indication of this important source of musical engagement for him.

Music as empowerment

Whilst Alan appeared to have found personal fulfilment and musical empowerment, arguably significant factors in adult musical identity construction, by re-establishing the intense relationship with the piano which had been interrupted since his schooldays, Paula described music as being ‘a love affair . . . on and off throughout my life’. She used it as a source of empowerment by merging it with her other interests as well as meeting new people and discovering new things. In her 30s she was to ‘rediscover [her] delight in the voice’ through her interest in yoga by chanting mantras and singing Bhajans, sacred songs, in the company of others. It was,

Something which is transcendental if you like, and it's this thing about joining with and blending with other voices and other aspirations if you like, which I find very very empowering, very beautiful.

Paula also used music significantly at turning points in her life. When she gave up school teaching and had time on her hands, she bought a second-hand saxophone after catching sight of one in a shop window. And ‘something new started in my life, and oh, gosh you know, it was a wonderful thing to do’. Later, when she was 45, she became interested in Dances of Universal Peace, which involved singing as well as dancing. Eventually, she trained and began to teach it to people with special needs. She used what had been her leisure pursuit to develop a new work identity with music.

Yet music was also painfully associated with Paula's husband with whom she had played the clarinet and shared her music listening. When she left him at the age of 49, she lost her voice and developed ME (chronic fatigue syndrome). For several years she found it difficult to sing which was very depressing for her (see Fig. 5). However, in her early 50s, Paula returned to the piano, attending two college workshops in succession. With her music learner identity strengthened, she bought her own piano and began private lessons, started music theory study and also joined a singing group. Her intention was to develop her music skills further in her sixties by doing a part-time music degree. It appears that despite having painful associations, music could provide Paula with a framework for personal development, give her a sense of purpose, and enrich her life.

Carla, who had also experienced painful associations with music, similarly used music for her personal empowerment at major turning points in her life. When she was 39, and living back in the UK, she left ‘the prison I'd been in for 40 years’, which also included her husband, marriage and small children. She discovered African music at WOMAD (World of Music Arts and Dance). It proved to be:

part of my opening up to, learning to dance for the first time, really to dance, you know, African kind of dance . . . being inspired by this music, and being, yeah, really turned on by it, I mean impassioned by it, excited by it, and liberated by it.

Later, she set up and ran a night club and disco with nine others who became her friends. Life seemed full of possibility:

It was late 80s, early 90s. . . . It was this whole, the Berlin Wall had come down, you know, it was almost like the world was going to change, and we were going to be part of it, and so we ran this place for a year, and it was one of the best things I've ever done in my life. . . . We had this thing where if your favourite record came on, you could leave everyone else to run the bar, and you could go up onto the stage and dance. . . . Bear in mind I'd come from this incredibly uptight middle-class life in K. I was up on the stage, in this disco, in fishnet stockings and heels that big, and a skirt up there, you know, 41 years old, dancing my socks off!

When Carla summed up what her musical life meant to her, it was apparent that music had not functioned solely as a means of occupying her spare time:

This morning, to have shared my musical life experience, I, you know, it's like I've been listening as well, I've been reminded of how rich it is, and how much I've done, and the opportunities I've had, and the variety and the – everything, bits of everything. There's been the painful piano lessons, there's been the romantic novel kind of stuff, there's been the rejections, there's been the successes, there's been the spotlight, there's been, freezing on the stage, all of those things. And, you know, all of this is part of what makes me who I am.

The richness of Carla's musical experiences established musical continuity in her life. Her river clearly shows how music came to be an important part of her self concept as a mature adult. About a year after data collection, there being changes in her personal life, Carla left the piano workshop with another new plan for music. This was to update and expand the collection of LP records her father had given her with the help of one of her two DJ sons.

Concluding issues and implications for music education

The ‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ and associated dialogue of the six respondents about aspects of their musical enculturation demonstrate the variety and complexity of the musical experiences they brought to their musical participation and learning as mature adults. Significant events and changes in their lives appeared to act as triggers to engage in new musical activity and achieve personal growth with the realisation of possible musical selves (see Markus & Herzog, Reference MARKUS and HERZOG1991). Changes in the respondents’ lives also prompted a search for musical continuity (see Atchley, Reference ATCHLEY1989) as they carried on with or returned to the instruments they had learned in the past, or had always wanted to learn. As they engaged with their music learning, they constructed their mature musical identity by regenerating and reconstructing their youthful musical selves as keyboard players as well as reinventing and empowering themselves as mature adult musicians.

Importantly, the findings reveal the respondents’ surprisingly strong resilience to negative musical experiences. Though it would be inappropriate to generalise from this small-scale study, it seems that not only can positive musical experiences (see Conda, Reference CONDA1997; Chiodo, Reference CHIODO1998; Cooper, Reference COOPER2001; Gavin, Reference GAVIN2001; Gembris, Reference GEMBRIS, Daubney, Longhi, Lamont and Hargreaves2008) be a powerful motivator and predictor for a return to instrumental tuition as an adult, but a prior lack of musical satisfaction can also be. This may occur in childhood with the instrument concerned, as in the case of Carla and James (also see Taylor & Hallam, Reference TAYLOR and HALLAM2008), or when engaging with other musical activities as an adult, as in the case of Alan (also see Richards & Durrant, Reference RICHARDS and DURRANT2003; Cope, Reference COPE2005).

A lack of musical encouragement or musical stimulation similar to that experienced by the respondents may lead some adults to regard themselves as being unmusical and therefore incapable of learning music. Tutors can address this problem and motivate their learners for music by making time for reflective discussion about the effect of past musical experiences on musical self-belief. ‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ can be used to advantage as a starting point, and barriers to learning and personal development through music caused by negative experiences and concomitant lack of musical self-esteem can be lowered with the benefit of shared hindsight.

The rivers of five of the six respondents demonstrated that musical self-affirmation was derived most often from informal learning and the support of important others such as family, friends and musical groups. I have found that encouraging collaborative creativity with groups of adult piano students using simple improvisation techniques in informal music making can be an effective and enjoyable way of increasing their musical self-belief. Open-ended tasks like this which take into account individual musical life experience, encourage peer support, and which allow mature adults some control in their learning, are important for their continued motivation for, and identification with music (also see Myers, Reference MYERS1989; Coffman, Reference COFFMAN, Colwell and Richardson2002; Taylor & Hallam, Reference TAYLOR and HALLAM2008). Shared informal learning with interested others from all over the world via internet forums can also reinforce and sustain adult musical identity through a cross-fertilisation of ideas. Such use of the internet has much potential for inclusion in music programmes for adults, and it is a valuable, though under-researched area of adult musical engagement.

An awareness of the breadth of musical experience and the expectations of adult music learners who self-identify with music is important in the light of increasing numbers of adults living longer who are interested in musical participation and learning. Researching musical life histories using ‘Rivers of Musical Experience’ with adults learning music in different contexts, for example ethnic instruments like the Tabla in the British-Asian community, would further elucidate how mature adults relate to music and what they require from it.

Acknowledgements

I should like to thank the respondents for taking part in this study with such enthusiasm, and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Appendix

Prompts for respondents

• What was it like to be doing ‘X’ musical activity?

• What did you like/not like about that sort of music?

• How did it make you feel about your music?

• What did you go on to do next?

• How do you feel that the music you have done/listened to in the past has affected you now?

• Looking back at your music, did anything happen that now seems surprising to you?

• Is there anything else that stands out as being particularly important to you in the development of your musical life as a music learner?