In 1906, governor of German New Guinea, Albert Hahl, opened a crate containing artefacts that he had formerly designated duplicates from his collection. Based on the island of New Britain in the Bismarck Archipelago, Hahl sought to take full advantage of the discounts on their exorbitant prices awarded by the shipping company North German Lloyd to the Berlin Ethnographic Museum. In addition to supplying artefacts to Berlin, Hahl had hoped to distribute objects to the ethnographic institutions located in Freiburg and Leipzig. The crate's content, however, proved highly disappointing, as representatives of the Berlin Royal Ethnographic Museum based in New Britain had extracted many of the governor's duplicates and added them to the official Berlin collection shipment before the crates were forwarded from the colony to Germany.Footnote 1 Hahl was mortified about the paltry number of artefacts about to land in Freiburg and Leipzig as he had promised their respective directors rich treasures. Hahl, who prided himself on a liberal policy on duplication, which was based on his own desire to raise public awareness of German New Guinea in the metropole, withdrew his trust in Berlin officials. Since these museum employees had desired omnia, they would henceforth receive nihil and Hahl decided against delegating future ethnographic shipments to Berlin museum representatives. From that moment on, the governor insisted on distributing artefacts and designated duplicates to ethnographic museums and collections of his choice.Footnote 2

The disagreement between the governor and Berlin museum officials was more than a fleeting dispute; it reveals deeply conflicting perspectives on duplication; that is, the process of determining what constitutes an ethnographic duplicate.Footnote 3 Contestations over duplication of indigenous artefacts revealed deep-seated epistemic rifts. As outlined in the introduction to the current issue, duplication in the collection-based sciences was a process that was far from obvious. It involved epistemic decisions concerning what exactly constituted a duplicate of a particular specimen, economic decisions where duplicates functioned as barter or monetary exchange with other scientific institutions, and political decisions regarding the issue of who ‘owned’ such artefacts or the right to determine the boundaries of the duplicate. The case of Governor Hahl outlined above falls mostly in the last, political, arena, as the colonial officer expressed bewilderment and profound anger to have his duplicate selection process tampered with by a scientific institution, since he fully expected to have material culture from New Guinea on display in as many German museums as possible. Exploring such tensions, this article maintains, reveals larger historical trajectories that illuminate current post-colonial debates surrounding ethnographic institutions and their collections acquired in colonial contexts. The decision of labelling a particular artefact a duplicate occurred not only in museum hallways, but also all along the chain of collection. The process thus reveals political contestations among colonial residents as well as a high degree of agency among indigenous producers of the much-sough-after commodities.

As will be delineated later in this article, museum-based ethnographic collection activity did not have clear-cut definitions of duplicates, which does not support elucidating this term. A working definition of the term would be two or more artefacts from a similar cultural context that share design as well as function and thus shared a close resemblance. Perhaps more appropriate would be employing the German term ‘doppelgänger’ to best illustrate the jagged contestations. More than a synonym for duplicate, the term raises unsettling notions. Literally translated as ‘double-walker’, the definition captures a non-biological lookalike individual, sometimes as a ghostly apparition, the appearance of which in literature usually portends tragic outcomes. While the doppelgängers collected in the islands of German New Guinea were not themselves harbingers of tragedy or bad luck, as they travelled from the hands of their indigenous producers to museum hallways, their appearance as ethnographic specimens did herald disputations, rivalry and disappointments. I use the term, therefore, to emphasize the contested nature of these artefacts and their capacity to disrupt, as well as to facilitate, the flow of imperial and scholarly discourse. After first situating German New Guinea in the ethnographic discipline, the following article explores duplication processes among ethnographic practitioners before moving to reveal contestations between ethnographers and colonial as well as commercial agents. Lastly, on a more ontological level, the duplication process is explored in some of the indigenous societies residing in the colonial territory. At the heart of this article stands the argument that much like collecting artefacts themselves, the issue of duplication was not a one-sided epistemic affair of metropolitan museum officials impressing their desires upon peripheral collectors and indigenous populations. Rather, European collectors in the colonies and indigenous creators actively engaged in the duplication process in order to profit from the metropolitan ethnographic demand for material culture. To focus the discussion of this important issue, I have selected the colony of German New Guinea, which supplied a minimum of 200,000 artefacts, many of them drawn into the process of duplication, to ethnographic institutions in Germany and elsewhere.Footnote 4 A concluding section will read such deliberation against the contemporary ethnographic museum context in order to demonstrate that these doppelgänger artefacts continue to operate as agents of alterity in post-colonial debates.

Situating German New Guinea

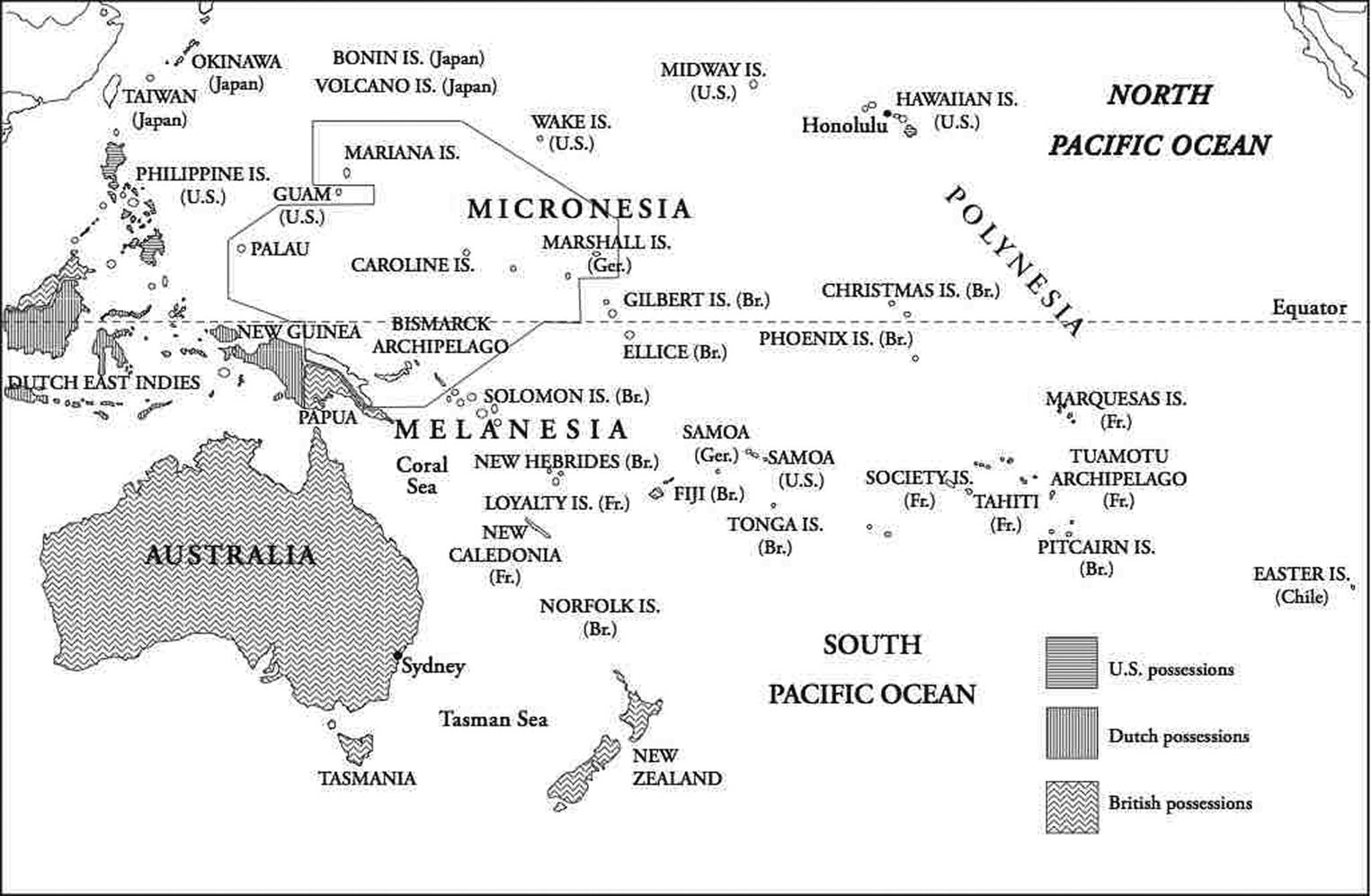

German New Guinea constituted a largely waterlogged colony, which covered many societies from the oceanic areas generally designated Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia. The history of this territory was gradual and expansive. As with most other German colonial regions, the territory was originally administered by a chartered enterprise: the New Guinea Company. However, this defrayed colonial administration failed, and by the turn of the century, the German state had involved itself directly in the supervision of the colony, appointing governors to facilitate this process. Meanwhile, the territory expanded since its early annexation in 1884–5. Initially, German New Guinea comprised mostly the north-eastern corner of New Guinea, the Bismarck Archipelago, and a sizable portion of the Solomon Islands. Following the Spanish–American War in 1899, the Spanish government sold the northern Mariana and Caroline Islands to Germany, which incorporated these into the existing territories under its administration. In connection with the annexation of the western portion of the Samoa Islands, which became the colony of German Samoa, the German government ceded some of the Solomon Islands to the British government as compensation. Lastly, by 1906, the company-controlled Marshall Islands had joined German New Guinea (Figure 1).Footnote 5 German New Guinea, unlike German Samoa, for instance, was thus one of the most culturally and linguistically diverse colonies in world. To reflect this reality, I shall employ the term ‘indigenous’ to contrast local populations with the European colonial residents. Where I can be specific as to the ethnic group involved, I will use the specific name.

Figure 1. The colonial boundaries of German New Guinea, boxed area, in the Pacific following 1906.

Ethnographic museum officials recognized the salvage paradigm as the very foundation for their scientific inquiries into human variation. They took for granted that the clash between European civilization and colonized cultures was a one-sided affair and that the former would eventually vanquish the latter in all of their cultural manifestations, including the artefacts they produced. The impact of this conflict was, according to ethnographic curators, uneven. While the expanding colonial powers quickly absorbed some societies, the integration of others was decisively slower. In particular, the islands of Melanesia were such a geographical area which, by the second half of the nineteenth century, stood only at the beginning of this predicted downfall and the missionaries, traders and colonial officials only at the beginning of their disruptive labour. Adolf Bastian, director of the Royal Berlin Ethnographic Museum, pointed out that in contrast to the frequently visited islands of Polynesia, the Melanesian regions of the Pacific were a premier place for a salvage operation:

The time has come for Germany to take its deserved place among other nations … Most importantly, we have to focus on the terra incognita of the Melanesian isles: specifically on New Guinea, New Britain, the Solomon Islands, and the New Hebrides.Footnote 6

Bastian was not alone in his belief that ethnographic collection should emphasize this neglected corner of the Pacific. Director of the Dresden Royal Natural History Museum Adolf Bernhard Meyer, who (unlike Bastian) had visited the region, greatly admired the cultural diversity he encountered in New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago and deemed this area one of great ethnographic interest because ‘the products of artistic activity are so exceptional and the different regions of this group of islands are so distinct from one another’.Footnote 7 In the early twentieth century, Emil Stephan, who guided the German naval expedition to New Ireland, elevated the salvage agenda to a ‘national burden of honor’ (nationale Ehrenschuld) in the closing pages of his work on South Sea art, pieces of which Germans had accrued by acquiring colonial territory in the Pacific.Footnote 8

Contested science: ethnographic and colonial doppelgänger

German colonialism and ethnography were mutually constitutive during the Wihelmine era. Nevertheless, German ethnography, as an entirely museum-based discipline, was able to filter out the colonial context and develop two competing epistemic paradigms based on artefact acquisition: non-Darwinian evolution and diffusionism. Both ideas coalesced in the above-mentioned salvage paradigm that resulted in a ‘doctrine of scarcity’ governing the purported limited availability of material culture. Such seemingly clear-cut scientific development was influenced by regional competition through civic pride, by increasing commercialization, and by a seemingly irrational appetite for accumulation that culminated in massive storage problems.Footnote 9

Similar clashes occurred in connection with duplicates. While museum officials attempted to apply natural-scientific criteria when deciding on duplicate artefacts, which were taken out of the regular museum, many argued that the term ‘duplicate’ simply did not exist in the realm of ethnography. Underscoring such problematic doppelgängers, Karl Weule, director of the Leipzig Ethnographic Museum, wrote that each expert knew that ‘duplicates do not exist in handicraft’ and that even a very loose conception of duplication could only be successful following a careful comparison of large series of similar artefacts.Footnote 10 Felix von Luschan, the director of the African and Oceanian division of the Royal Berlin Ethnographic Museum, echoed Weule's scepticism towards the very existence of duplicates. For instance, when the general director of the Berlin museums, Wilhelm Bode, pressured Luschan to speed up the selection of duplicates to relieve his division's crowded conditions, the ethnographic museum official vehemently retorted that there were simply no duplicates in his division:

Concerning your suggestions that I should surrender ‘duplicates’ from my division and reduce my demands for more [storage] space, I regret to say that I am unable to do so. I have never retained duplicates and have no interest in doing so in the future.Footnote 11

While denying the existence of duplicates on a scientific level, museum officials had to accept duplication in the quotidian affairs of museum administration. The above dispute between Luschan and Bode underscores this point. Bode, as a trained art historian, was both appalled and flabbergasted at Luschan's refusal to identify and surrender duplicate artefacts to relieve the overcrowded condition at the Berlin Ethnographic Museum. Additionally, duplicates became a kind of currency in their exchange with other institutions. Catherine Nichols has expertly shown how duplicates were employed as barter items to fill in significant gaps in the Smithsonian Institute by exchanging, for instance, Native American artefacts for objects from Dutch Indonesia with the Leiden Ethnographic Museum in Holland. Likewise, smaller museums who could not reciprocate in kind were expected to provide alternative service by asking their Congressional representatives to vote in favour of the Smithsonian when funding decisions were debated. This process of deaccessioning duplicates, the Smithsonian curators maintained, prevented the needless amassing of artefacts, while also creating prominent local, national and global alliances.Footnote 12

Colonial politics equally infused the problematic doppelgängers. Germany had a unique distribution modus that tied the colonies directly to the capital, Berlin. The Federal Council's decree of 1889, also described by Katja Kaiser in this special issue, stipulated that all ethnographic or natural-scientific artefacts collected by colonial civil servants or by members of federally sponsored expeditions had to be delivered to the Berlin museums first before duplicates could be distributed to other German institutions.Footnote 13 Renewed and emphasized in colonial publications in 1904, the decree was much hated by colonial residents and stoked resentment towards aloof museum curators and their supposedly lofty scientific ideals.Footnote 14

Above all, it was Luschan who managed to offend most colonial officials. In his 1904 instruction for ethnographic collecting and observations he stressed that such a centralization of artefacts in Berlin was necessary to avoid the regrettable splitting of collections that followed James Cook's expeditions to the South Seas in the eighteenth century and the punitive expedition to Benin in the nineteenth.Footnote 15 Luschan maintained that a centralization of objects in Berlin would not only prevent the dismembering of collections but also allow for the emergence of a complete ethnographic picture of the German protectorates, which clearly would assist the colonial administrations in Africa and the Pacific. Similarly, Luschan enumerated the laborious tasks associated with classifying, cleaning and restoring the artefacts before duplicates could be surrendered to smaller institutions. Because of this labour-intensive work, he insisted that the task of determining what constituted a duplicate sat squarely with the Berlin institution.Footnote 16 The growing and repetitive colonial arsenal of arrows and lances could be released as duplicates to other museums in compliance with the centralization edict and it was precisely this convenient outlet that would return to haunt Luschan, almost evoking the supernatural overtones of the doppelgänger. Leipzig director Weule, who on the surface agreed with Luschan's designation of duplicates, grew tired of Berlin's uninspiring and illiberal policy of doppelgänger distribution, a sentiment shared by many of his colleagues at other German museums. Indeed, with poetic license, Weule characterized Berlin's practice as ‘only with a broken dart will we part’ (ausser ein paar zerbrochen Pfeilen nichts zu verteilen).Footnote 17 Hamburg Ethnographic Museum director Georg Thilenius, in a letter to the deputy secretary of the German colonies, underscored the need for a transparent policy of duplication:Footnote 18

At the core of this dispute is the concept of ‘duplicate’. Without doubt the Federal Council assumed a rather extensive version of this term in contrast with the Berlin museum, where [Luschan] is of the position that the duplicate does not exist.Footnote 19

Thilenius and Weule were at the forefront of a number of museum directors calling for a disbanding of the centralization edict that would ultimately culminate in the partial overthrow of the Federal Council's decree by 1910.Footnote 20

Contested collecting: epistemological concerns in colonial ethnography

Initially, colonial residents welcomed ethnographic investigation. As sociologist and German studies scholar George Steinmetz has succinctly argued, while considering psychological factors in his study of colonialism, German colonizers attempted to control the production of knowledge over the colonized Other and, most importantly, endeavoured to prevent the colonized population from moving freely between European and non-European categories.Footnote 21 Colonial residents required clear-cut ethnic hierarchies that combined observed as well as projected characteristics to support colonial projects of conversion, commercial extraction and colonial governmentality. The cultural multiplicity of the territory made this task a difficult proposition.Footnote 22 Colonial residents did not share in the ethnographers’ scientific outlooks over indigenous material culture as they saw little use in evolutionary or diffusionist theories. Such conceptual clashes are perhaps best exemplified by the second governor of German New Guinea, Albert Hahl (in office from 1902 to 1914), who attempted to integrate ethnography with colonial administration. He kept an active correspondence with ethnographic authorities and, as the beginning of this article indicated, became increasingly incensed about Berlin's centralization edict. A legal scholar himself, Hahl dabbled in comparative anthropology and supported ethnographers, such as Richard Thurnwald, who professed an interest in indigenous legal conceptions.Footnote 23 The governor unsuccessfully attempted to push ethnography away from its emphasis on salvage of material cultures, and the concomitant emphasis on evolutionary and diffusionist frameworks, toward avenues more useful to his administration. Hahl, like many other colonial governors, displayed a clear preference for population statistics, indigenous legal conceptions, and linguistic constructs rather than collecting artifacts.Footnote 24

The contested process of establishing doppelgängers, already challenging among museum practitioners in Germany, emerged most conspicuously in the arena of ethnographic collection. Resident collectors vehemently resented the one-sided knowledge production of purported experts located at prominent museums and regarded trained ethnographers as competing collectors. Museum curators, such as Luschan, did not help matters with their insistence on the strict execution of the Federal Council's decree. Naval-surgeon-turned-ethnographer Augustin Krämer said it most aptly:

Colonial civil servants rarely welcome [ethnographic] researchers with open arms partially because they consider them competitors not within the discipline but in the collection of ethnographica … [Such officials] will always accept the geologist or the astronomer as absolute authorities and regard the zoologist and the botanist as untouchable experts. But ethnography is a specialty that they claim to have mastered just as well.Footnote 25

Krämer voiced what other trained ethnographers were experiencing in the colony: the dispute of expert status and a competitive atmosphere governing ethnographic collections.

The deprecatory attitude toward ethnography among colonial residents and the competition over material culture resulted from what Emil Stephan, leader of the German naval expedition to New Ireland (1907–9), wrote to Luschan: ‘Among 100 people here at least 99 are guided by self-interest. Indeed, if they are interested in anything else but making money then it is certainly not the lives and tribulations of the dirty kanakas’.Footnote 26 His use of this particular term to describe the local population was a forceful statement, which sought to distance his ethnographic approach from the attitude of the European residents. The competition over ethnographic objects also clouded terminology for material culture. Europeans residing in German New Guinea referred to artefacts as ‘firewood’ (Feuerholz) and professional collectors as ‘Professor Firewood’, or, in a more derogative fashion, as ‘firewood bandits’.Footnote 27 This term also influenced indigenous populations who would refer to the ethnographer in Pidgin English as ‘Master Firewood’.Footnote 28 This term might have sounded derisory on the surface. At the same time, it highlights the subliminal hostility against professional ethnographers in the colony. In addition, the expression is indicative of an almost pathological fear that a positive evaluation of local material culture could upset the carefully calibrated hierarchy impressed upon the heterogeneous population in German New Guinea.Footnote 29 The label ‘firewood’ was meant to pacify such disrupting positive cultural observations and highlight contested artefact collecting, which in turn influenced the determination of duplicates or doppelgängers.

Museum ethnographers would ultimately turn the term ‘firewood’ on its ear to undercut the quality and expertise of local European collectors The signifier experienced transformation, as it no longer functioned to denigrate trained ethnographers nor stymie the potential of local material culture to upset colonial hierarchies. ‘Firewood’ in the context of the museum was deployed to belittle European residents’ poor and repetitive collecting methods, which led to undesirable and therefore unsalable duplication. As Dresden museum director Arnold Jacobi put it, ‘bows, thick bundles of bamboo arrows, and room-high lances from Melanesia, the “firewood” of the experts’.Footnote 30

This appropriation of ‘firewood of the experts’ seemingly emerged during the interwar period, but the critical attitude of the museum community and the colonial residents’ ‘secondary’ – meaning uninformed – collecting had been present long before that, especially due to the predominance of useless duplicates in their acquisitions. For instance, when, in 1896, the resident commercial Hernsheim Company attempted to sell a commercially acquired collection from the ethnographically interesting western islands of the Bismarck Archipelago for no less than 20,000 marks, Felix von Luschan ridiculed the assemblage as ‘too much arsenal and not enough science’.Footnote 31 Further, he insisted that the company ‘had collected in the most abominable fashion. They deprived the poor [local] people of thousands of weapons … enough to supply all museums in the world’.Footnote 32 Emphasizing the useless quantity of doppelgängers was meant to disparage and thereby lower the price of commercially acquired collections.

Departing clearly from the scientific concerns of the ethnographic museum curators, colonial residents’ much more liberal policy of duplicate distribution needs clarification. The above episode illustrated that commercial companies shared little of the ethnographers’ scientific outlooks but sought to monetize indigenous material culture. Company directors found, however, that museum officials were ‘notorious price bargainers’ (Preisdrücker).Footnote 33Although several resident companies sought to export collections to Germany, their expected profit margins shrank considerably and the practice was, by and large, abandoned by the early twentieth century.Footnote 34 In the short-lived commercial aims governing commercial companies’ ethnographic collection practice, duplicates played a subordinate role. Little concerned about duplication, commercial companies treated artefacts as commodities and forwarded large collections, including numerous duplicates, to German museums.

Among colonial civil servants, who were more affected by the centralization edict than German museum staff outside Berlin, duplication of artefacts was pivotal. Governor Albert Hahl, despite his misgivings about an ethnography centring entirely on artefact collection, still acquired indigenous objects. However, he did so not to further the scientific goals of museum officials, but out of his desire to raise the status of the Pacific colony in the eyes of a German public who regarded it as much less important than the empire's African possessions. An encounter between Hahl and Kaiser Wilhelm II in 1902, recorded in the governor's memoirs, is very telling in this regard. The kaiser expected quick expansion and economic development from the newly appointed governor of German New Guinea. Hahl, however, maintained that the territory's topography, its geographical dispersion and the (in the governor's perception) low cultural standing of the indigenous populations prevented quick fixes. Wilhelm II seemed displeased.Footnote 35

The large ethnographic interest in German New Guinea, however, provided Hahl with an additional way of getting his supposedly neglected territory noticed. The proliferation of ethnographic museums and collections in Germany since the second half of the nineteenth century provided for free advertisement of the colony through exhibition space. In 1910, for instance, the governor wrote to Karl Weule in Leipzig that he did not want to see his services monopolized by a single institution. ‘I have, as much as possible, attempted to deliver the ethnographic treasures of the protectorate to German museums … I am very much concerned about an equitable distribution [of the artefacts]’.Footnote 36 The governor was deeply concerned to provide, particularly, what could be regarded as ‘showy’ artefacts to German museums, since such objects were most likely to end up on display rather than in storage rooms.

Two prominent examples of objects collected by Hahl are the hermaphroditic uli figures from New Ireland and the famously tall hareiga display pieces of the Baining of New Britain. The hareiga headdresses of the Baining varied from ten to nearly forty meters in height. The weight of such artefacts was such that carriers had to be held up by several people supporting the artefact with large bamboo sticks. Not only did the hareigas’ size make them particularly hard to ship out of the territory, but also their widely varying size technically eliminated these rare figures from ethnographic duplicate selection. Hahl, not bothered by such ethnographic duplicate considerations, had these impressive headdresses carried overland to the colonial capital, Rabaul. Once there, Hahl's depot administrators distributed them among museums located in Leipzig, Lübeck and Munich.Footnote 37 In Berlin, ethnographic museum director Luschan attempted to prevent Hahl's liberal vision of duplicates by enforcing the centralization edict, but Luschan superiors felt that the issue would not sit well with colonial authorities. In New Guinea, Hahl applied similar criteria to the uli figures of New Ireland. Even if current experts have identified no less than fourteen different types of uli figure, the governor's broad concept of duplicate employed only a single type of differentiation – the hermaphroditic characteristic of female breasts and a pronounced male phallus – to regale multiple museums with these important figures (Figure 2).Footnote 38

Figure 2. Uli figure on display on board the North German Lloyd Steamer Sumatra. The two unidentified individuals holding the carving are probably unidentified Sumatra crewmembers placed there for scale. Dieter Klein Collection.

Traces of Hahl's liberal distribution activity can today be found in the museums of Berlin, Freiburg, Leipzig, Lübeck, Munich and Stuttgart, and the artefacts are witness to his effort to split collections for greater propagandistic effect. Such intentions could only clash with the centralization edict. When Hahl saw his 1906 shipment compromised, as recounted at the outset of this article, he elected to no longer accept the route stipulated by the Federal Council's edict, which would channel his ethnographic treasures through the German capital. Instead, Hahl opted to bundle shipments of artefacts through the governmental depot located in Rabaul (Simpsonhafen), the main shipping node in German New Guinea, and bypass Berlin and its avaricious museums altogether.Footnote 39 Much to the chagrin of Luschan, there was little that Berlin officials could do about such obvious violations. Although he dutifully reported Hahl's infringements against the centralization edict to his superiors, the German Colonial Office, established in 1906, had other worries associated with the fallout of the brutal repression of uprisings in German South West and East Africa.Footnote 40

In his efforts to supply as many museums as possible with indigenous material culture, Hahl also resorted to the distribution of artificial duplicates, in the sense that they were deliberately crafted by the indigenous peoples as doubles rather than being retroactively designated such from a set of collected objects: dwelling and ship models from German New Guinea. Although, especially in connection with canoe miniatures, some models had application in indigenous societies for instruction and play, the house and ship models commissioned by Hahl were entirely manufactured duplicates. Museum curators were aware that these artefacts were entirely produced to serve decorative purposes and did not address ethnography's need for authenticity.Footnote 41 Authenticity, of course, was itself a fuzzy concept that ethnographers sought to bring into focus. An authentic object was considered one of an appropriate age to have fulfilled its specific cultural role or ritual.Footnote 42 Although practitioners rarely addressed the relationship between authenticity and duplicates, the assumption was that a young and ritually ‘unfinished’ artefact made for an equally imperfect duplicate.

In the early twentieth century, the influence of European wares on the production of ethnographica became an additional, highly influential criterion influencing authenticity. An early collector of ethnographic objects, Otto Finsch, claimed already in the 1890s that carvings made with iron tools were ‘rushed and less detailed, obviously, as in every place where the peoples of nature chose to replace their primitive tools with iron ones’.Footnote 43 The use of European tools and the potential lack of ritual use of several uli figures led Leipzig museum curator Ernst Sarfert to comment to the sender, a prominent ship's captain:

It seems that the natives are transitioning to the modern fabrication of the [uli] figures. All smaller figures never transcended toddler age and were therefore produced in the very recent past. Fortunately, the lovely Prussian blue [an industrial colorant] can only be detected on a few figures and in only a few spots.Footnote 44

This quote speaks volumes about the expanding notion of authenticity and indigenous adaptations to European demand, which will be discussed later. The notion of ‘toddler age’ employed by Sarfert suggests that the artefacts he received were never utilized in any cultural context. Indigenous producers carved them to satisfy European demand.

Little bothered by ethnographic concerns for authenticity, Governor Hahl enlisted his colonial civil servants and the missionary societies stationed in the territory in overseeing the production of the fabricated duplicates of house and canoe models. For instance, in August of 1909, Wilhelm Wostrack, a colonial civil servant stationed in central New Ireland, communicated to Hahl that local chief Bosle had completed a reduced model of a men's congregation house typical of the region of Namatanai, where Wostrack was based, and was shipping the same to the colonial capital, Rabaul. Wostrack further promised model houses from the southern region of New Ireland and the offshore Tanga Islands.Footnote 45 The governor also insisted on his own brand of authenticity: all model dwellings had to be constructed by employing indigenous people and with local materials. Such instructions became apparent when a set of house models arrived in Rabaul from Georg Zwanzger, a colonial civil servant stationed in the Admiralty Islands. Government stock keeper Mahler informed the shipping company that one of Zwanzger's models had been destroyed because ‘[f]or its construction, machine cut wood replaced genuine indigenous materials. With the approval of the governor, this [house] model was deemed unusable’.Footnote 46 Hahl's commission of ‘artificial’ duplicates may have not fulfilled the demands of ethnographic museums for authentic artefacts, but they still performed an important propaganda role when exhibited in museum hallways, potentially luring more German individuals to travel to New Guinea. Museum officials were conscious about these artificial reproductions. They felt, however, that house and canoe models would make museum displays more engaging for the visitor.

Hahl's approach to material culture that sought to boost New Guinea's appeal in the public eye was, by and large, not shared by the colonial officials toiling under his command. Most of the colonial servants, however, were indeed prolific ethnographic collectors, yet they were motivated by more mundane incentives that require explanation. Scientific ethnographic concerns, and even the governor's propagandistic concerns, did little to impress the colonial gentlemen. Their admittedly more limited reason for collecting was based on colonial worth and its outward recognition through state decoration. The German museum landscape was unique in that it could employ a plethora of state orders and decorations to reward collectors. Since most German states kept their own decoration systems following unification in 1871, the still-intact kingdoms, duchies, grand duchies and principalities that constituted the empire could engage such orders to secure collections for the museums located in their realm. These medals could also be strategically employed to counter the centralization of artefacts in Berlin.Footnote 47

For colonial civil servants, especially those operating in the more distant Pacific territories, orders took on a high degree of conspicuous consumption that rivalled even the strangest indigenous cultural practices in German New Guinea. Craving such decorations became a metaphorical ailment often referred to as ‘heavy chest’, ‘chest pains’, or ‘button-hole affliction’, as the lower classes of the knight's orders were carried in the buttonhole of one's overcoat.Footnote 48 Civil servants bitterly complained that the reprisal campaigns against Nama and Herero, today considered genocidal, amongst others in German South West as well as East Africa, provided ‘every lieutenant of the Protective Forces [Schutztruppe] who fights a little with the [Prussian Order of the] Red Eagle’.Footnote 49 For those based in New Guinea, on the other hand, ethnographic collecting became a means to earn one of the coveted state decorations or, through a careful division of the acquired ethnographic trove into duplicates, more than just one state medal (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Example of conspicuous consumption. At the centre, with a heavy chest, Franz Boluminski clearly stands out. To the left of him is probably Wilhelm Adelmann, who complemented his medal obtained through ethnographic collecting with the colonial medal introduced after 1912. Noticeable also is Albert Hahl, located at the very left of the picture, who forewent showcasing his own decorations to highlight those worn by his officers. Dieter Klein collection.

With a total of nine medals between the two of them, or more than half of all decorations awarded for ethnographic collecting, Franz Boluminski and Arno Senfft, who were district officials in New Ireland and the island of Yap respectively, are perhaps the best examples of colonial officials who decided to divide their ethnographic acquisitions into roughly equal duplicate collections to obtain a greater yield of German state medals (Table 1).

Table 1. Ethnographic collections and medals for colonial officers serving in German New Guinea.

Franz Boluminski had been in the territory since the 1890s working in several functions for the New Guinea Company, which had administered the colony since its annexation in 1884–5. When the German Reich assumed direct administration roughly fifteen years later, Boluminski was tagged to serve as the colonial official in the northern region of New Ireland, the Nusa/Kavieng station, an area that was vital for recruiting labour as well as for plantation development. By chance, Boluminski's assignment in this area also placed him at the centre of two vibrant indigenous material-cultural practices: the uli and the malagan. Both cultural practices were associated with funerary ceremonies of powerful men, involving the crafting of elaborate rituals and carvings. Malagan carvings covered a wide array of objects – masks, statues and friezes – and were generally discarded following the ritual circle; that is, once the figures finished circling though the mortuary rituals, they were generally destroyed or left to decay. The presence of a demand for these expressive figures presented another opportunity: barter for European goods. Uli, on the other hand, as displayed in Figure 2, were less elaborate carvings, but their pronounced hermaphroditic features were highly sought-after by ethnographic collectors. Unlike malagan carvings, uli were not cast off following the funerary events, but were retained for the next occasion. This also contributed to the fact that malagan figures were a great deal more plentiful that uli.Footnote 50 Boluminski collected both of these artistic expressions and divided his collected artefacts among many museums for maximum effect. In terms of uli figures, Boluminski took Hahl's superficial criteria, which referred only to the hermaphroditic nature of the figure, to designate duplicates. Edgar Walden, as member of the German naval expedition to New Ireland (1907−9) organized by the Berlin museum, in 1908 had the opportunity to visit Boluminski's shack, were he kept his uli and malagan treasures. Walden noted six to seven uli in the dwelling, but the colonial official told him to pick only three of these carvings, since the others would be forwarded to the Stuttgart museum. Noticing Walden's distress over this situation, Boluminski allowed him to also take some malagan carvings to make up for the shortfall.Footnote 51 Walden, who bitterly complained about the colonial official's collection and duplicate distribution patterns, was stopped by Luschan before the situation escalated: ‘I urge you to get along with Mr. Bolu[minski]. Please keep in mind the influence that man wields [in New Ireland].’Footnote 52 Much like Hahl, Boluminski's liberal efforts at duplicating his collection won out over Luschan's very narrow scientific conception of the term and highlight the contestations associated with such doppelgängers.

Similar experiences concerning duplicates also emerged in the case of Arno Senfft. Much like Boluminski, Senfft arrived in the new colony to work for the New Guinea Company in the 1890s. By 1895 he had moved to the Marshall Islands and started to collect local artefacts. A few years later he contacted the Berlin Ethnographic Museum about his collection and inquired whether he would be allowed to divide his collection to benefit other institutions with duplicates. In Berlin, Luschan proved unwilling to concede the privilege of doppelgänger distribution to a colonial resident: ‘Ethnographic objects distinguish themselves through specific intricacies that only an expert can evaluate. It is therefore important to leave the decision whether or not a piece is a duplicate to the specialists.’Footnote 53 Luschan's patronizing attitude concerning duplication did not sit well with Senfft, who would soon find ways to bypass such limitations. When the German Reich acquired the Caroline and Mariana Islands from the Spanish Crown following the disastrous Spanish–American War in 1899, Senfft was ordered to take over the colonial office for the western Carolines located on the island of Yap, from where he also oversaw the Palauan Islands. Supervising this – from a German perspective – novel ethnographic area, Senfft was unwilling to have Luschan select duplicates for other museums as he realized that any ethnographic or natural-scientific collection that landed in Berlin first would remain there.Footnote 54 Stuttgart ethnographic collection manager Karl von Linden concurred with Senfft that ‘Luschan plays the thundering Achilles and has torn [our] friendship asunder. The umbilical cord between Berlin and Stuttgart will be more difficult to repair than between Yap and Singapore or Sydney’.Footnote 55 Much like Hahl and Boluminski before him, Senfft decided to split his ethnographic treasures into duplicate shipments and forward collections directly to those museums that would promise a coveted decoration. In order to be in compliance with the federal decree, Senfft contacted Luschan about his intentions, but could not hide a certain degree of criticism: ‘Am I allowed to forward duplicates to Stuttgart again? They are quite enterprising in their writings from [Stuttgart] and I would very much welcome a similar engagement from your part.’Footnote 56 For colonial officials, state decorations obtained through ethnographic collection fulfilled a deep longing for public recognition of their work in a distant colony.

Contested design: indigenous considerations on duplication

To talk about duplicates in the indigenous context seems absurd, especially since Western criteria surrounding such artefacts seldom applied to local cultural considerations. In the multiple indigenous contexts of German New Guinea, objects were rarely, if ever, considered duplicates, even if there is evidence of individually and communally owned patterns and branding.Footnote 57 There are numerous studies of non-European societies that problematize the dichotomy between original and copy. Zuni artists, for instance, value repetition and do not regard close adherence to an original form as a cultural offense. Similarly, the Kwoma residing in East Sepik Province in Papua New Guinea hold that the essential features of evaluating a particular work of art are whether the carver has the sanctioned authority to perform the work and whether the rendition is closely allied to the original. Carvers generally produced copies of the original to replace a weathered item that was formerly left to rot or, in more recent times, passed on to a European collector.Footnote 58 Investigators looking more broadly at collection areas in the Pacific caution against setting indigenous ontologies apart from European ones since it disallows recognition of artefacts of encounter or entangled objects that potentially bridge this divide.Footnote 59 Duplication of crafts, although different in the indigenous and European contexts, highlights the indigenous responses to increasing European demand for their material culture. While it is difficult, in fact almost premature, to speak of a market for ethnographic objects in the early twentieth century, the rising demand for material culture in German New Guinea, and for that matter elsewhere in the world, created new outlets for traditional artefacts. The remainder of this article will look closely at the indigenous context where European products were copied, where artefacts were produced exclusively to satisfy European demands, and where artefacts which had reached the end of their ritual cycle were disposed of by selling them to Europeans. Doppelgängers in the indigenous context acquired the status of bargaining chips in the emerging colonial exchanges.

The islands of Wuvulu and Aua located at the western end of the Bismarck Archipelago came to the attention of the ethnographic community in the 1890s. Their material culture, which included shark-tooth-adorned weapons, suggested an affinity with the Micronesian islands located to the north. German museum officials assumed that these two special islands represented a clear-cut ethnographic boundary between Melanesia and Micronesia and urged investigation as well as further ethnographic collection. Spearheading such investigations was the commercial company Hernsheim & Co., the representatives of which hoped to profit from this sudden ethnographic interest. As mentioned earlier, unlike colonial officials, commercial agents did not have to comply with the centralization edict emerging out of Berlin. Turning ethnographic objects into commodities, however, proved disappointing. Their ethnographic collections – hastily assembled and poorly described – triggered scorn and rejection among museum ethnographers. To make matters worse, their endeavours provoked excess, such as the desecration of grave sites by traders in search of artefacts, which encouraged, for instance, Auan outrage that resulted in the death of a merchant and violent German punitive retribution. Similarly, the pathogens introduced as a result of increased collection activity took a high toll among the Wuvulu and Aua populations.Footnote 60 Prior to their tragic population decline, Wuvulu and Aua peoples responded rapidly to the increasing demand for their material culture. Despite the prediction that commercial companies would plunder the islands of material culture, Richard Parkinson, a prominent resident ethnographer, who arrived in the area at the turn of the century, noted that the inhabitants had skilfully reproduced the desired artefacts and, surrounding his vessel, peddled many of them for European wares. Most noticeable were also reproductions of European trade wares, which baffled the observer. Clearly the bush knives, fashioned out of wood, could not have the same efficacy as the iron counterparts. Yet the reproduction followed the original even in the smallest detail, including rivets and, on occasion, the commercial branding of the company producing the bush knife (Figure 4).Footnote 61 While Parkinson wondered about the purpose of the wooden reproduction, he collected some examples as curiosities, thus probably fulfilling the intended purpose of the indigenous duplicates.

Figure 4. Wooden duplicate of a bush knife on Wuvulu, reproduced from George Thilenius, Ethnographische Ergebnisse aus Melanesien, Halle: Karras, 1903, p. 266.

The Wuvulu may have been unique in their duplication of European trade wares, but production of duplicate objects to meet European demands for local material culture occurred elsewhere. A good example of such manufacture emerged from the Admiralty Islands in the Bismarck Archipelago. The inhabitants of these islands were best known for their fabrication of obsidian-tipped weapons that can be observed in Figure 5, where obsidian-tipped lances were displayed alternating with larger wooden counterparts. Ethnographic collectors paid particular interest to weapons, spears and daggers made with obsidian blades because it compounded the narratives of cannibalism that engulfed these islands. The harrowing description accompanying these weapons only increased their European demand. Supposedly the obsidian spears were not designed to bring about instant death, but would shatter upon impact. The wound produced by the weapon would fester due to the multiple tiny obsidian fragments, thus ensuring an agonizing and painful death from infection.Footnote 62

Figure 5. Indigenous trade involving obsidian-tipped weapons with the North German Lloyd Steamer Sumatra in the Admiralty Islands. 2798_008 Karl Nauer/Südsee Museum Obergünzburg.

Archaeologist Robin Torrence, in her research about obsidian-tipped spears and daggers from the Admiralty Islands located in museums worldwide, divided the ethnographic collections from this archipelago into six distinctive periods spanning the sixteenth to the late twentieth centuries. Although outright commercialization of these artefacts emerged only after the Second World War, she noticed that significant changes to manufacture occurred during the two periods that roughly covered the German colonial period (1876–1920). The Admiralty Islands became incorporated in the territory of German New Guinea in 1885, a period that ended with the Australian occupation of the archipelago in November of 1914. The most important event occurred towards the end of the German period with the opening, in 1911, of a government station, which led to an increased labour-recruiting effort as well as an expansion of plantations throughout the archipelago. This period also saw a substantial increase in ethnographic collecting. Processes of simplification and standardization characterizing obsidian-tipped spears and daggers meant a high degree of similarity among the artefacts. The actual killing purpose of the implements decreased, while decorative patterns and therefore collectability were on the increase. This trend was most noticeable in the production of obsidian-tipped daggers, whose quantitative representation in collections was greatly augmented, with simplified and standardized designs, during the German colonial period.Footnote 63 Demand for such objects increased partially because of the expanding trading stations opened in the Admiralty Islands (Figure 5). Similarly, as the Admiralty Islands were included in the expanding shipping connections throughout the Bismarck Archipelago, the local population were able to peddle their priced obsidian-tipped artefacts to ship personnel and some of the first tourists joining this vessel.Footnote 64

The changes triggered by the demand for Admiralty Islands artefacts did not go unnoticed by members of the Hamburg South Sea expedition, which visited the island group in 1908. Remarking that traditional material culture was disappearing, the expedition participants surmised that this decline was caused by the combination of tropical and externally introduced temperate diseases, rather than indigenous industry. On the other hand, the demand for material culture led to ‘adventurous forms’ unknown to Europeans that were by now ‘mass produced’ and probably never ran any significant cultural cycle.Footnote 65 This obvious effort toward duplication was soon misunderstood in the German press. When a Hamburg daily newspaper picked up the news from official expedition reports, simplification and duplication transformed into fodder for accusing Admiralty Islanders of skilful art forgeries.Footnote 66

The examples from the western region of the Bismarck Archipelago speak to duplication of artefacts to meet increasing European demand. The malagan carvings associated with mortuary ritual reveal yet another, perhaps more subtle, way of duplication. Anthropologist Susanne Küchler advocates for recognition of a particular sacrificial economy for the artefacts associated with the malagan ceremonies. Objects manufactured for each prominent funerary ceremony were removed from the enclosures after running their particular cycle and were either destroyed or left to decay. Following their ritual use, malagan carvings had become almost like dead skin that had to be shed. Most importantly, Küchler emphasized that destruction and decay could also be substituted through barter and sale to Europeans.Footnote 67 While sacrificial deposition of an artefact did not speak to duplication, the design and manufacture of the malagan carving were greatly influenced by European demand, which triggered similar simplification and standardization in design encountered in the Admiralty Islands. The contemporary examination of collections hailing from German New Guinea provides additional cues. Anthropologist Vicky Barnecutt has carefully analysed malagan collections from New Ireland made during the nineteenth century. Unlike the prediction of German ethnologists, who sought to salvage the last vestiges of authentic New Ireland material culture during the first decades of the twentieth century, Barnecutt reveals that the introduction of iron tools, as well as Western materials – whether it was cloth, industrial blue colouring, beads or glass – could in some cases be observed as early as the 1860s. For the manufacturing of wooden masks and friezes associated with the ceremonies she claims that, in fact, ‘Very few New Ireland objects in museum collections appear to have been carved using stone tools’.Footnote 68 While not all objects bear traces of the use of Western materials, there seems to have been no prohibition against these materials in the manufacture of ritual objects, thus greatly enlarging the realm of material combination which even before colonial annexation would be found in masks and carvings collected by Europeans.Footnote 69 Barnecutt further adds that there was possibly experimentation in malagan production roughly between 1870 and 1880, where the local populations not only employed iron tools but also incorporated beads, cloth and commercial colourants in the manufacture of the carvings. The rejection of such ‘novel’ artefacts, however, by European collectors as adulterated objects triggered a return to formerly employed aesthetics in a conscious effort to appease European demands. This ‘new traditionalism’ not only signalld the abandonment of iron tools in production, but also suggested a tightening of stylization and standardization that invited duplication.Footnote 70

Duplication and colonial collections in contemporary ethnographic museums

The doppelgänger artefacts of German New Guinea proved, as the term foreshadows, to be both a benefit and a curse for ethnographic collectors. Moving beyond the supernatural connotations of the term, doppelgängers traced the contested nature of the process of duplication all along the chain of collection. Museum officials frequently argued that artefacts created by human hands could not and should not be divided into duplicates. However, the pressures to relieve cluttered museum halls of objects, the need to establish alliances with other institutions, and the incentive to offset budgetary shortfalls through the objects’ sale forced the curators’ hands. The shorthand definition of duplicates as artefacts from a similar cultural context that shared design and function ironically applied more to the context of colonial officials and commercial agents, who showed little care for scientific debates and collected objects for monetary or self-fashioning gain. European colonial residents displayed a much more liberal conception of duplication than ethnographers in order to engage as many museums as possible. Many indigenous societies residing in German New Guinea traditionally held no cultural prohibitions against copying, replicating or otherwise duplicating artefacts. The increasing demand for indigenous material culture by Europeans actively encouraged engagement in the process of duplication.

Moving the duplication process beyond museum hallways and exploring it all along the collection chain reveal additional benefits from those listed above. Current debates surrounding the fate of cultural artefacts acquired during colonial times have reached a fever pitch. While museum curators have argued for decades that ethnographic museums took on a universal curatorship for cultures worldwide, a stance that represents an extension of the salvage paradigm, this argument has been forcefully challenged over the last three decades. A critical response to this stance argues that colonialism taints all objects collected during this historical phenomenon. The argument continues that colonialism created inequitable conditions encouraging ethnographic trophy taking during military raids and rendering even peaceful barter between indigenous and European parties suspect. These perspectives treat colonialism as a monolithic entity that either has little interaction with the ethnographic endeavour or leaves indigenous societies with little choice but to surrender their artefacts to collectors.

Recent calls to reach beyond collective provenance histories of ethnographic objects alert us to the potential cultural histories of colonialism inherent in the artefacts.Footnote 71 Studying the contested histories of duplication reveals such possibilities. In terms of the interaction between European colonial residents and ethnographers, tensions over which artefacts to designate duplicates simultaneously uncover and support the assertion that a cultural designation of colonialism is best characterized by cooperating and colliding agendas displayed by different colonial actors. This tension has significant repercussions for the indigenous populations. Duplicates in the indigenous context may have had a radically different meaning than in the European realm. The indigenous duplication process also points to a high degree of agency and dynamics behind the production of material culture that demands inclusion in contemporary museum exhibits.

Acknowledgements

This paper greatly benefited from the comments of Ina Heumann and Anne Greenwood MacKinney, as well as of all the participants of the Berlin workshop in November of 2020. The editors of this journal and two anonymous reviewers greatly improved the final version.