At first sight, events involving Edward Arden, a Catholic gentleman from Warwickshire executed for treason in December 1583, look like an instance of a man drawn into a fight he could not win. The alleged feud between Arden and the earl of Leicester has been consigned to the status of a local affair, and the role of the earl in Arden’s downfall as gossip put about by Leicester’s enemies.Footnote 1 New research into the Catholic Arden family during the Dudley ascendancy in Warwickshire has revealed a conflict in which the Ardens’ descent from a Saxon magnate known as Turchil was used to challenge the Dudleys’ local dominance as well as the legitimacy of their national position at the centre of Elizabeth’s government. Turchil was one of the leading landowners in Warwickshire in 1066 and one of the few Saxons to retain his estates after the Conquest.Footnote 2 He later became central to the descent of the earls of Warwick back to the legendary Guy that was created by the Beauchamps, the family to whom the Dudleys owed their claim to the earldom (Appendix I).Footnote 3 In 1559, Robert Dudley was appointed lord lieutenant of Warwickshire and in December 1561 Ambrose Dudley was created earl of Warwick.Footnote 4 In 1562 both brothers adopted the Beauchamp badge of the bear and ragged staff, a motif they proceeded to use whenever possible.Footnote 5 The extravagant use of the bear and ragged staff to stamp the Dudley presence on virtually everything they owned, including items such as nightshirts and nightcaps, showed a commitment to the Beauchamp heritage that can seem comical.Footnote 6 In September 1564, Robert became earl of Leicester.Footnote 7 These titles and the lands granted with them, including the neighbouring castles of Kenilworth and Warwick, made Robert and Ambrose the leading magnates in the Midlands (Appendix II).Footnote 8 Their shared sense of purpose was second to none but it was Robert who became the source and target of Edward Arden’s antagonism.

By bringing the dispute between Edward Arden and the earl of Leicester out of the shadows of speculation about Shakespeare’s family, this article seeks to widen the debate on the nature of political conflict during the 1570s and early 1580s. It focuses on the connection between contemporary rumours concerning the Dudleys’ social origins, the historical associations of the Warwick and Leicester earldoms, genealogical research undertaken for Arden and the Dudleys from around 15722–1582, and Philip Sidney’s Defense of Leicester in order to show how Edward Arden used his lineage to contest the Dudleys’ authority.Footnote 9 Sidney’s Defense is a source of rare value for understanding the issues at stake and the article makes the case for re-dating this crucial tract.Footnote 10 By placing the genealogical research commissioned by the Dudleys and Sidney’s Defense within the chronology provided by the political tracts A Treatise of Treasons (1572) and Leicester’s Commonwealth (1584), described by Peter Lake as the ‘second instalment’ of the Treatise, the attack on the Dudleys’ ancestry can be seen as part of the wider debate on legitimate authority.Footnote 11 Events involving the Dudleys and Edward Arden showed the apparent reality of the dangers of Protestant new men to the ancient Catholic gentry. In exploring these events, the need for the Dudleys to exert their authority over Edward Arden provides a specific context for Simon Adams’s observation of the Dudleys’ emphasis on their Saxon ancestry in the 1570s.Footnote 12

Despite Arden’s portrayal in historical accounts, epitomised by Alice Fairfax Lucy’s description of him as ‘poor, proud and defenceless’, Arden was a member of the Midlands’ most important Catholic political network.Footnote 13 He inherited his estate in 1563 from his grandfather, Thomas, a Warwickshire magistrate for over thirty years, and the family was deeply embedded within the county elite. Arden’s father-in-law, Sir Robert Throckmorton, was de facto leader of the county and had been one of Queen Mary’s most prominent supporters.Footnote 14 Sir Robert’s first wife, Muriel, mother of Arden’s wife Mary, was the sister of Lord Berkeley (d. 1534). Arden’s brothers-in-law included Sir Thomas Tresham, Sir William Catesby and Ralph Sheldon. His legal counsel was his cousin, Arden Waferer, principle man of business to Christopher Hatton.Footnote 15 Around 1574, his eldest daughter, Katherine, married Edward Devereux, youngest son of the first viscount Hereford by his second wife and uncle (though near contemporary) of Walter Devereux, first earl of Essex (d. 1576).Footnote 16 The Devereux were Protestants but by the mid-1570s Essex had a deep dislike of the earl of Leicester.Footnote 17 Arden was also connected to Edmund Plowden through their common kinship with Ralph Sheldon and in 1579, Arden, Plowden, Tresham and another brother-in-law, Sir John Goodwin, became joint trustees of Sir Robert Throckmorton’s estate.Footnote 18 Sir Francis Willoughby, nephew of the duke of Suffolk (exec. 1554) and Sir Henry Goodere (d. 1595) were also close associates of Edward Arden.Footnote 19 Goodere, patron of Michael Drayton, had a career in Elizabethan politics that is still not fully understood. He appears to have been closest to Lord Burghley but was briefly imprisoned for his role in the duke of Norfolk/Mary, Queen of Scots marriage plan.Footnote 20 Goodere’s participation in the earl of Leicester’s expedition to the Netherlands has been seen as indicating his reconciliation with the earl but was more likely a reflection of his connection to Burghley.Footnote 21

These relationships connected Edward Arden to those at the heart of the Elizabethan polity. For these men, the public proclamation of descent was central to the struggle for political dominance during the reign of Elizabeth. However, political theory that generally focuses on the ideologies created by different religious groups has left a gap between theory and practice through which lineage has fallen, leaving genealogy defined as predominantly a cultural rather than political pre-occupation.Footnote 22 Moreover, pedigree rolls have been identified as an under-used manuscript source and although historians have acknowledged the symbolism of descents reaching back into antiquity, their political purpose has been only sporadically addressed.Footnote 23 Consideration of heraldic devices assigned by the Elizabethans to figures from the past can be fraught with difficulty, given that heraldry was a medieval practice in which even the earliest devices can only be traced to the twelfth century. Some heralds, particularly Robert Glover, Somerset herald from 1570–1588, have become renowned and Glover set new standards for genealogy.Footnote 24 Nevertheless, Tudor pedigrees have a mixed reputation and even the exceptional Glover was constrained by the culture in which he worked. The Dudleys were earls and Arden only an esquire yet both understood the essential role that lineage played in the prevailing ideology of power. Lineage was fundamental to their dispute and belongs to what Rees Davies usefully termed ‘the sociology of aristocratic lordship’.Footnote 25 Gentleman were those ‘whom their blood and race doth make noble’ and Sir Thomas Smith noted that men recently awarded arms were ‘called sometime in scorne gentlemen of the first head’, a description used to describe John Dudley, duke of Northumberland, in Leicester’s Commonwealth.Footnote 26 For Edward Arden and the earl of Leicester, lineage—‘the conjunction of blood and tenure’—was not a matter of fashion but the basis on which both were asserting their political and territorial rights.Footnote 27

The ascendancy of the Protestant Dudleys in a county in which the leading political network, led by Arden’s father-in-law, Sir Robert Throckmorton, was predominantly Catholic, had an effect on the county gentry which was reflected in the composition of the commission for the peace.Footnote 28 Tudor government relied upon the gentry in their role as magistrates and their co-operation with members of the council, a world where the magistrates needed ‘to learn the social skills that gave them access and effect at local and national levels’.Footnote 29 Edward Arden and his friends and relations had been learning those skills for generations and believed that local power was their right. At the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign the Throckmorton kinship network accounted for around a third of Warwickshire magistrates. By 1574, few of this group remained and the list of justices submitted to the council by Edward Aglionby in 1575 was almost entirely composed of known Dudley clients.Footnote 30 The gentry were essential to the smooth administration of the counties—‘the men without whom nothing was possible’—and the marginalisation of the Throckmortons and their connections was a serious assault upon the political hierarchy in Warwickshire.Footnote 31 Arden and his friends and family were not outsiders looking in, they were insiders being forced out.

However, even though the descent of the Arden estate was not unbroken, nor Arden’s family history unblemished, Edward Arden’s ancestry enabled him to challenge the earls of Warwick and Leicester.Footnote 32 Although Robert Dudley has been described as ‘less obviously a baseborn new man’, some of his contemporaries would not have agreed.Footnote 33 In November 1569 the earls of Westmorland and Northumberland warned of the danger to the queen and the ancient nobility of ‘new set up nobles’ that may have been aimed at the Dudleys.Footnote 34 In the early 1570s A Treatise of Treasons and The Table gathered out of the Treatise of Treasons recast the well-established ‘evil councillor’ discourse as an ‘evil base-born councillor’ discourse.Footnote 35 In the 1590s Sampson Erdeswick repeated an earlier rumour that the duke of Northumberland had falsely created his descent from Lord Dudley and that Edmund Dudley’s father, John Dudley of Atherington was not a gentleman but a carpenter.Footnote 36 Robert Glover was identified by Erdeswick as the source of at least the first part of this rumour and Glover had certainly met Erdeswick by 1579.Footnote 37 The attack on the Dudleys’ origins was two-pronged, challenging their descent from the Suttons of Dudley as well as their presentation of the descent of the Warwick earldom and corresponded to the charge of ‘want of gentry’ challenged by Philip Sidney in the Defense of Leicester. William Camden later assigned attacks on the Dudleys’ social origins not only to the earl of Sussex but also to Edward Arden, who had ‘opposed him [Leicester] in all he could, reproached him as an adulterer, and defamed him as an upstart’.Footnote 38 In 1604, in a document attached to a letter to James I from Henry Goodere, heir to his uncle and namesake, Leicester’s animosity towards Edward Arden was attributed to the earl’s belief that ‘Mr Arden could lay some clayme to the Earldom of Warwick’.Footnote 39

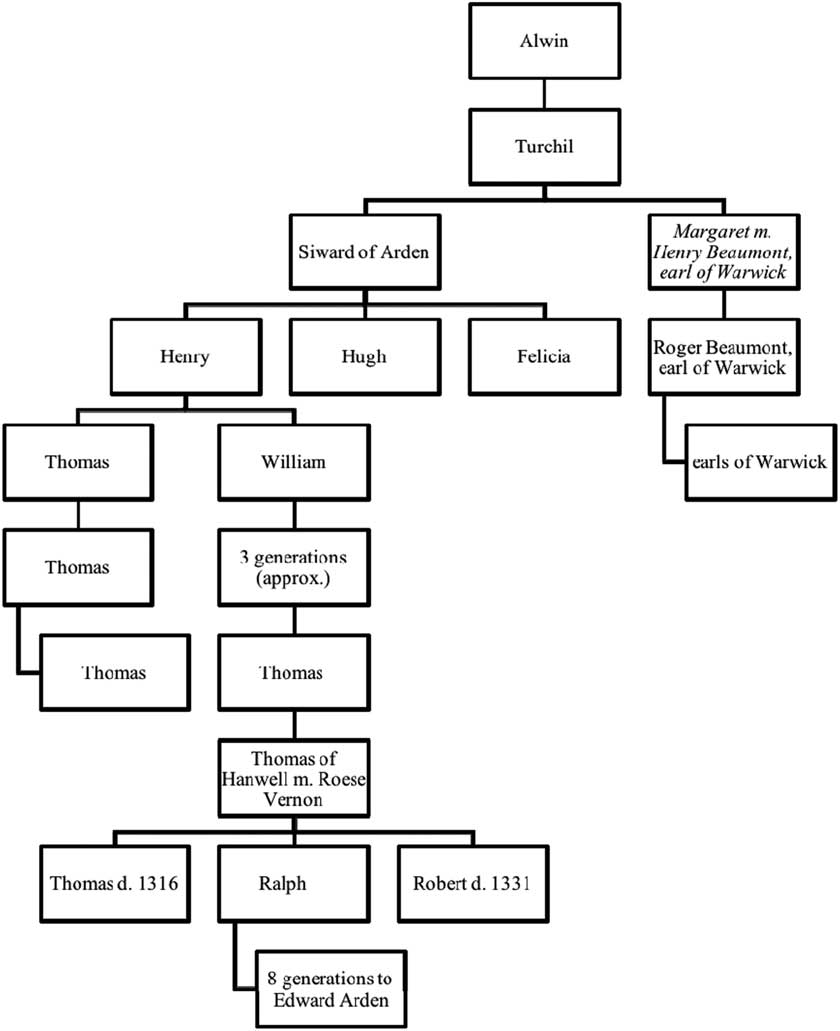

Arden’s alleged claim to the earldom of Warwick came from his Saxon ancestor, Turchil (Appendix III).Footnote 40 In 1086, Turchil was the dominant magnate in Warwickshire.Footnote 41 However, Turchil’s son, Siward, lost most of the family’s estate to Henry Beaumont, the first Norman earl of Warwick.Footnote 42 Siward and his sons were absorbed into Beaumont’s affinity and despite fluctuations in both their fortunes and their relationship with the Warwick earls, the Ardens remained an important family in the county and adopted a coat of arms that inverted that of the Beaumonts (Figure 1).Footnote 43

Figure 1 Arms of Edward Arden, c. 1579, bottom, quartered with Throckmorton. Detail of the lattice paned windows with roundels and shields of heraldic glass in the Drawing Room at Coughton Court, Warwickshire; image 153793. © National Trust Images/Andreas von Einsiedel

Siward and his descendants retained some of Turchil’s land, including Curdworth in north Warwickshire, in the forest of Arden from which the family took their name.Footnote 44 In the fifteenth century, the scholar-priest John Rous created a seamless link between the Saxon magnate Turchil and the Norman earls of Warwick by falsely depicting Henry Beaumont’s wife, a Norman noblewomen called Margaret, as Turchil’s daughter on the armorial rolls commonly known as the Rous rolls.Footnote 45 Rous’s account of Oxford halls may have recommended him as a scholar to Richard Neville, earl of Warwick (d. 1471) and his wife, Anne, daughter of Richard Beauchamp (d. 1439), and in the mid-1440s he was appointed chantry priest at Guy’s Cliffe.Footnote 46 His rolls, probably prepared in Warwickshire in the 1480s for Anne Beauchamp, gave a visual representation of the history of the earls of Warwick from the legendary Saxon warrior, Guy.Footnote 47 Anne’s commission reflected the unusual significance of the female line in the descent of the earldom of Warwick, plausibly suggested as the rationale for the production of the rolls.Footnote 48 Edward Arden’s real Saxon ancestors, Alwin and Turchil, as well as the re-cast Margaret, were shown as part of the earldom’s lineage from Guy of Warwick, providing a vital source later used by both Arden and the Dudleys (Figure 2).

Figure 2 British Library, MS Additional 48976, fols. 29–34, Alwin, Turchil, Margaret, Henry Beaumont, Roger Beaumont on the English Rous roll. © British Library Board

The Beauchamp appropriation of Turchil as the link back to Guy of Warwick reflected earlier borrowings from the Ardens already integrated into the legend. Guy, described as ‘England’s other Arthur’, merged pre-Conquest figures with medieval political pre-occupations and was still evolving during the sixteenth century.Footnote 49 Most versions focus on the story of Guy, son of Siward of Wallingford, who married the beautiful Felicia, daughter of the earl of Warwick, and through her acquired the earldom.Footnote 50 As Judith Weiss has discussed, Guy’s father possibly drew upon the real Siward, son of Turchil, ‘So the name of the hero’s father, Sequart, in our romance [Gui de Warewic] may have been indebted to Siward, a figure once of much local consequence in the area where the poem was written.’Footnote 51 Siward’s daughter, Felicia, has also been suggested as the most likely model for Guy’s wife, Felicia.Footnote 52 The story was widely disseminated among both an elite and a popular audience and was strongly connected to Warwickshire.Footnote 53 Edmund Spenser, Michael Drayton and Shakespeare all refashioned or reused elements of the legend in their own writing.Footnote 54 It was so central to English culture that the chapel on the supposed site of Guy’s hermitage was later spared as an ‘antiquity’ by Civil War troops.Footnote 55 The Ardens had a unique family identity that reflected their ancient connection to Warwickshire and Turchil’s manor of Curdworth was still the most important manor in Edward Arden’s estate.

The terms of Arden’s tenure played a central role in the dispute between Arden and Leicester. After Arden’s death, the earl was accused of wanting his land and the inquisition into Arden’s estate in 1584 described Curdworth as ‘holden of her ma[jes]tie in fee socage in the righte of the mannor of Sutton Coldfield somtyme p[ar]cell of therldom of Warwick’.Footnote 56 From the mid-1570s until around 1582, Edward Arden was subject to a series of legal challenges that destabilised his tenure of his estate. By 1575 he was involved in a territorial dispute with his neighbour to the west, Edward Holte, brother-in-law of Henry Knollys and a close associate of the Dudleys.Footnote 57 Arden’s refusal to wear the Dudley livery, an outright rejection of their lordship, is traditionally dated to the same year.Footnote 58 In 1576 Arden and Holte agreed to arbitration, with Holte represented by George Digby and Arden by his brother-in-law, Thomas Throckmorton, in pairings that reflected the growing fissure in the county.Footnote 59 Holte’s action against Arden was followed by similar actions from Ralph Rugeley and Raphael Massey, men who were also connected to the Dudleys.Footnote 60 In 1578 Ralph Rugeley accused a group of Arden’s tenants of trespass, initiating a dispute that continued until the early 1580s and moved from Warwick assizes to Star Chamber.Footnote 61

In the summer of 1578, Arden was among the Midlands’ gentry who tried to prevent the earl of Leicester from acquiring Drayton Bassett, a manor on the Warwickshire– Staffordshire border to the north of Curdworth and one of the Dudleys’ most important purchases in the region.Footnote 62 There is far more to be said about events at Drayton than can be addressed here, but Arden’s involvement confirms his position among the region’s leading gentry and the tension caused by the Dudleys’ territorial expansion. The acquisition of Drayton was accompanied by two serious riots and intermittent disorder in the summer of 1578, apparently orchestrated by north Warwickshire and south Staffordshire gentry and more or less ignored by Lord Paget and the Staffordshire justices until the Privy Council intervened.Footnote 63 Those accused of furthering the disorder at Drayton were substantial men. Chief among them were Sir Francis Willoughby, Walter Harcourt, William Stanford, Henry Goodere, Edward Arden and the families of Pudsey, Gibbons and Harman who were the leading gentry in the town of Sutton Coldfield.Footnote 64 These men had strong links with the court and the legal establishment. Sir Francis’s sister, Margaret Arundell, was a member of Elizabeth’s privy chamber and he later appealed to her for help.Footnote 65 Walter Harcourt was the son of Simon Harcourt (d. 1577) of Stanton Harcourt and William Stanford was the son of the Marian judge, Sir William Stanford (d. 1558).Footnote 66 Some of the men involved at Drayton were known or suspected Catholics (Arden, Harcourt, Stanford and Goodere) but others were not, including Sir Francis Willoughby and the men from Sutton Coldfield, although none could be described as advanced Protestants. Rather, one geographical factor united all of these men and that was the potential threat to their autonomy should the Dudleys attempt to enforce their overlordship through the earldom of Warwick, as their estates and the town of Sutton Coldfield all fell within the earls’ former park of Sutton Chase.Footnote 67 The enforcement of feudal tenures was used as late as 1590 when Ambrose Dudley claimed the lands of the Catholic Thomas Trussell through knight’s service after Trussell was convicted of felony.Footnote 68

During the same period, Edward Arden was trying to consolidate his own position. By 1574, Arden’s eldest daughter, Katherine, had married Edward Devereux, drawing Arden closer to the Devereux affinity and providing a possible conduit for the passage of Essex pedigrees connected with the Warwick earldom into the hands of Robert Glover. Documents relating to the marriage were witnessed by Arden Waferer.Footnote 69 In November 1574 Edward Arden became sheriff of Warwickshire.Footnote 70 At the same time, rumours about the earl of Leicester’s involvement with Essex’s wife, Lettice Knollys, began to be circulated and were referred to in later letters between the earl and Thomas Wood.Footnote 71 In 1576 the Dudleys’ patronage connections with the reforming Protestants were shaken by the suppression of the prophesyings and Arden was appointed to the Warwickshire bench.Footnote 72 Although Arden was unable to maintain his position as a justice, it is likely that he still had access to influential connections. In autumn 1580, Henry Goodere and the lawyer Robert Stanford (d. 1616) were appointed to resolve the continuing dispute between Arden and Ralph Rugeley.Footnote 73 Stanford was ‘the conforming head of a Catholic family’ who was said to be closely linked to Lord Paget.Footnote 74 He was also the brother of the William Stanford who had been one of the chief agitators at Drayton. When Goodere and Stanford were appointed to lead the commission to resolve Arden and Rugeley’s dispute, Goodere, Arden and William Stanford had very recently been under investigation for their role in the disturbances at Drayton Bassett.Footnote 75 Given that the appointment came from Star Chamber, this suggests competing power structures and complex political relationships both at court and in the Midlands.

As Arden and the Dudleys contested their positions in Warwickshire, the place of Turchil in the descent of the earldom of Warwick became the cause of detailed investigation. Arden benefitted from a Dudley claim that was neither straightforward nor unassailable and that reflected the complicated history of the Warwick earldom. In 1565, the Dudleys’ brother-in-law, the earl of Huntingdon, investigated his own right to the earldom through his great-grandmother, Margaret, countess of Salisbury.Footnote 76 A rift between Huntingdon and the Dudleys seems unlikely, even if their relationship was more ambivalent than generally believed. However, given that Huntingdon’s claim to the throne was central to his depiction in Leicester’s Commonwealth, his interest in the Warwick earldom, itself a step on the way to his recognition as heir to the duke of Clarence, may mean that Huntingdon really did have ambitions currently still obscured.Footnote 77 Other possible claimants included the Howards, whose arms included the chequy or et azure that showed descent from the counts of Meulan, used ‘by the related comital houses of Leicester, Warwick and Warenne’ from the twelfth century.Footnote 78 As well as the counts of Meulan, the Howards could claim descent from Joan Beauchamp, daughter of the eleventh earl of Arundel and coheir of her brother, twelfth earl of Arundel and ninth earl of Surrey.Footnote 79 Joan was also the wife of William Beauchamp, Lord Bergavenny, son of the eleventh earl of Warwick and ancestor of George Talbot, sixth earl of Shrewsbury.Footnote 80 These connections were complicated but no more so than those proclaimed by the Dudleys. The death and attainder of Norfolk in 1572 eliminated any Howard threat but Shrewsbury’s connections were a potential thorn in the Dudleys’ side. The marriage of John Talbot, first earl of Shrewsbury, to Margaret Beauchamp (daughter of Richard Beauchamp and Elizabeth Berkeley and the woman from whom the Dudleys claimed the earldom), had contributed to uncertainty over the descent of the Beauchamp and Berkeley lands that the Dudleys themselves exploited in their revival of the Berkeley lawsuit.Footnote 81 After Ambrose Dudley’s creation as earl of Warwick, Robert wrote to the earl of Shrewsbury to inform him that Elizabeth had restored the Dudleys to ‘the name of Warwick’.Footnote 82 Leicester’s Commonwealth explicitly depicted Shrewsbury, ‘a man of the most ancient and worthiest nobility of our realm’, as another of Leicester’s political victims and an example of ‘how little accompt he [Leicester] maketh of all the ancient nobility of our realm’.Footnote 83 Martha Driver has identified a Talbot claim to the Warwick earldom in a poem of John Lydgate’s written for Margaret Beauchamp and Griffith has also suggested that ‘the decorative images in the mid-fifteenth-century Shrewsbury Talbot Book of Romances (British Library, Royal MS 15. E. VI) reveal, albeit obliquely, a competing interest to the earldom during the Kingmaker’s lifetime’.Footnote 84 The common ancestry of the Talbots and the Dudleys was acknowledged by the earl of Leicester’s use of Shrewsbury’s manuscripts and several Talbot descents were copied in the 1570s, including by Robert Glover as part of his research into the descent of the Warwick earldom.Footnote 85

The statement of the younger Henry Goodere that Arden had some claim to the Warwick earldom makes it tempting to assume that such a claim was made. This was not the case. Arden’s response to the Beauchamp appropriation of Turchil was not to lay claim to the earldom of Warwick but to refute Turchil’s status as earl. This was made explicit in Glover’s later research and was referred to in the Arden pedigree in the visitation of Warwickshire made in 1619, in which Turchil was described as ‘by some formerly and ignorantly made Earle of Warwick but certayne it is he was Lord of Warwick at the conquest tyme’.Footnote 86 By acknowledging that Turchil was lord of Warwick but not the earl, Arden had two aims that were nevertheless closely linked. The first of these was to prove that as Curdworth had descended to Arden through Turchil, who had held the manor before the earldom of Warwick existed, the Dudleys’ had no rights over either the manor of Curdworth or Arden. The second of Arden’s aims, part of his defamation of the earls as upstarts, was to show that Dudley pedigrees were fictional documents designed to uphold a lordship that they did not possess and to which they had no right.

Between 1572 and 1582, the heralds Robert Cooke and Robert Glover produced, copied and consulted a wide range of documents connected with the descent of the Ardens and the Dudleys (Appendix IV).Footnote 87 By the late 1570s Glover’s friend, the Warwickshire antiquary, Henry Ferrers, was also researching Warwickshire pedigrees. In 1577/8, Ferrers produced a list of the peerage and gentry of Warwickshire that may have been preliminary research for a longer study to include a history of the earls of Warwick.Footnote 88 Griffith has questioned ‘disinterested antiquarianism or scholarship’ as an adequate explanation for such projects and Ferrers’ involvement moved the pursuit of Warwickshire pedigrees from the professional circle of the heralds into the gentry and the peerage.Footnote 89 Henry Ferrers came from a long-established Warwickshire family connected to the same circle as Edward Arden.Footnote 90 Ferrers’ uncle, Lord Windsor (d. 1575), was an unrepentant Catholic who lived in Italy for much of Elizabeth’s reign, where he was visited in the early 1570s by Philip Sidney.Footnote 91 By the early 1580s the new Lord Windsor, Ferrers’ cousin, was part of the circle of his other cousin, the earl of Oxford, and Philip Howard. In 1581 Windsor was both Oxford’s second in the Callophisus challenge organised by Philip Howard and in which Philip Sidney took the role of the Blue Knight, and one of the four Foster Children of Desire in the court entertainment written by Sidney.Footnote 92 Henry Ferrers’ research, undertaken during a time when Arden’s dispute with Leicester and friction at court was at its most intense, may have been politically motivated.Footnote 93

Glover and Cooke produced at least five full descents between 1572–82 (four for the Dudleys, one for Arden), of which three were finished products. Around eight related documents and notebooks also survive, including detailed copies of Arden’s charters and it is possible more remain to be found or re-categorised. Attribution of some manuscripts to individual heralds is a challenge. Uncertain attributions have become widely circulated and not enough attention has been paid to the context of production.Footnote 94 Personal relationships between the heralds and patronage relationships with the nobility involved with the College of Arms were complicated and sometimes difficult.Footnote 95 The heralds had multiple professional connections with the Marshal’s office, assorted patrons and ancillary staff including painters and draughtsmen as well as their private practices as genealogists.Footnote 96 Finished pedigrees were written using a formal hand that throws up only minor differences for comparison. Notes taken for personal use show wide variations in script, depending on the type of document being consulted or copied and the prevailing working conditions. A certain amount of collaboration took place and finished pedigrees were probably not the work of a single person. A detailed pedigree of the earl of Leicester from the mid-70s is considered to be Cooke’s research written by Glover.Footnote 97 However, comparison of this pedigree with MS Codex 1070 suggests that they were written by the same person and the Codex is currently attributed to Cooke (Appendix V).Footnote 98 A summary of MS Codex 1070 also exists yet these documents have never been studied together.Footnote 99 In the early 1580s Glover produced a pedigree for Arden which he credited to himself and Cooke but which is entirely in Glover’s hand (Appendix VI).Footnote 100 This pedigree not only contradicted the pedigrees produced in the early to mid-70s, it also contradicted Cooke’s notes and made claims for Arden that were potentially deeply offensive to the Dudleys. Cooke and Glover made copious notes on the same descents and they may have had different approaches to reconciling their genealogical research with their professional and patronage connections. Cooke’s well-known patronage relationship with the Dudleys may have made him more reluctant to challenge their descent.Footnote 101 Glover’s reputation for independence and his research into the Warwick and Leicester earldoms and the Sutton barony as well as his work for Edward Arden suggests that his relationship with the Dudleys was ambivalent. Although Glover produced a descent of the Sutton barony in 1581 and drafted a dedication to the earl of Leicester for a collection of European lineage disputes in January 1582, it is not clear that these works were either finished or presented to the earl.Footnote 102 In contrast to Cooke, most of Glover’s material can be seen in notebooks that reveal the extent of his research and the breadth of sources consulted. Glover’s closest political connection was Lord Burghley and it was Burghley who had arranged the appointment of Glover as Portcullis pursuivant in the 1560s.Footnote 103 In 1587, under attack by his fellow herald William Dethick, Glover asked Burghley for protection ‘wher I never yet missed it in tyme of need’.Footnote 104 Glover’s research into the genealogy of the Dudleys and Edward Arden may have required the protective cover of Burghley’s patronage and in 1584 Glover drafted a letter to the earl of Leicester refuting an accusation of Catholic sympathies.Footnote 105 Both heralds also used the Rous rolls. In 1572 Robert Glover made his own copy of the English roll.Footnote 106 Glover’s books, inventoried shortly after his death in 1588, revealed his copy of the English Rous roll as well as the first known mention of the Beauchamp Pageants, suggesting ‘a particular interest in Rous’s histories of the Earls of Warwick’.Footnote 107 On Robert Cooke’s death in 1593, the English Rous roll was among his papers.Footnote 108 The Latin roll may already have been in the hands of Edward Arden. It was referred to in the Visitation of 1619 and in the 1630s it was owned by Edward’s son, Robert Arden.Footnote 109

The earliest finished pedigree from the manuscripts under consideration is MS Codex 1070, helpfully dated 1573 and provisionally attributed to Cooke. It was made for the earl of Leicester and presented ‘proof’ of his descent from the early earls of Leicester and Chester. Turchil is described as ‘Turquinus, erle of Warwike’, a description repeated on the highly detailed pedigree produced for Leicester in the mid-1570s.Footnote 110 Turchil appears on this pedigree with the shield chequy or et azure a chevron ermine assigned to Guy of Warwick on the Rous Rolls and incorporated by the Dudleys into their own arms (Figure 3 & Figure 4).

Figure 3 College of Arms, MS 13/1 (detail) . Turchil as earl of Warwick on pedigree prepared for Robert, earl of Leicester, c. 1573–6. © College of Arms. Reproduced by permission of the Kings, Heralds and Pursuivants of Arms.

Figure 4 Portrait of Robert Dudley, earl of Leicester, with coat of arms showing quartering of chequy or et azure a chevron ermine, artist unknown, c. 1575. © National Portrait Gallery, London.

Notes of Cooke’s from around the same time refer to Turchil as ‘Turquenus’, in ‘a brief rehersall of the erles of Warwyk from Guy erle of Warwyk, who lyved in the year of o[u]r lord god 924’.Footnote 111 During the same period, Glover copied several pedigrees concerned with the earldom of Warwick’s descent.Footnote 112 One of these was obtained by Glover from Lord Dudley via a source whose name has been redacted. This descent, supplemented down one side by that of the Berkeleys, ended with the Dudleys’ elder brothers, Henry, Thomas and John, and probably dated from the 1540s.Footnote 113 Another Warwick descent, which also included the early descent of the earls of Leicester, was copied from a pedigree owned by the earl of Essex (d. 1576), given to Glover by Essex’s secretary, Edward Waterhouse.Footnote 114 It shows Turchil as ‘Tarquin, earl of Warwick’ with the arms assigned to Guy of Warwick. A detailed Talbot and Beauchamp pedigree in the same notebook also included ‘Tarquin’ as earl of Warwick.Footnote 115

In order to uphold their right to the earldom, the Dudleys needed to portray themselves as heirs to the legendary Guy. As Griffith has written, ‘By the middle of the fifteenth century Guy had effectively become the property of the earls of Warwick, just as Warwick itself had become their town’.Footnote 116 In 1565, the year of Ambrose Dudley’s marriage to Anne Russell, William Copland printed the first complete text of the legend, including an ‘injunction to the reader to inspect in Warwick a tapestry depicting Guy’s battle with a dragon’.Footnote 117 During Elizabeth’s visit to Warwick in 1572, the Recorder Edward Aglionby welcomed her with a speech so partisan as to suggest that it had been submitted to the Dudleys for approval. In a potted history of the town, Aglionby noted its existence as a Roman town named Carwar, its renaming as Warwick by the Anglo-Saxons, ‘of noble earles of thesame, namely one Guido or Guye’, of ‘the countenance and liberality of the Earles of that place, especially of the name of Beauwchampe’ and the honour done to the town by Elizabeth’s creation of a new earl, ‘a noble and valiaunt gentleman lyneally extracted out of the same house’.Footnote 118 The Dudley devotion to Guy was such that until 1590 Ambrose Dudley was still paying the salary of the keeper of Guy’s sword.Footnote 119 However, the Beauchamp establishment of Turchil and his father Alwin as the links between the post-Conquest earls and the legendary Guy created an unusual problem for the Dudleys because Edward Arden was still alive, still in Warwickshire and still a Catholic.

Although the Dudleys continued to claim a pre-Conquest ancestry through the existing connection between Guy of Warwick and the Warwick earldom, the weaknesses in the Dudleys’ position gave the Leicester earldom a new prominence in their search for authority in the Midlands. Both earldoms were essential to the Dudleys’ ascendancy in the region as well as crucial elements in legitimising their rights to office. The earldom of Leicester had already been the focus of the lavish Eulogia created by William Bowyer in 1567 and this was followed by the 1573 descent claiming Robert Dudley’s ancestry from the earlier earls of Leicester and Chester.Footnote 120 The descent made frequent allusions to offices held by these earls and reflected the Eulogia in which the connection between the earldom of Leicester and the lord stewardship was emphasised.Footnote 121 The antiquity and royal connections of the earldom of Leicester were also re-stated. As the descent noted, the earldom of Leicester was not in abeyance before the grant to Robert Dudley in 1564 but functioned as part of the earldom then duchy of Lancaster, into which it had been incorporated during the later thirteenth century.Footnote 122 It also re-affirmed the historic connection between the earldoms of Warwick and Leicester through the description of Robert Beaumont’s brother, Henry, earl of Warwick, from which Henry ‘is descended Ambrose Erle of Warwicke brother to Robert Erle of Leicester’.Footnote 123 The Beaumont connection formed the central motif for the 1573–6 pedigree (Figure 5) which showed the descent of the Sutton barony, the source of the Dudleys’ claim to nobility through their father’s family.Footnote 124

Figure 5 College of Arms, MS 13/1 (detail) . Central stem of pedigree prepared for earl of Leicester with central figure of Robert, earl of Leicester and Sayerus Sutton, Lord of Holderness. © College of Arms. Reproduced by permission of the Kings, Heralds and Pursuivants of Arms.

Robert Beaumont, ‘le Bossu’, earl of Leicester, (d. 1168) is the central figure of twenty-one nobles and the visual layout suggested that the earldom of Leicester was connected to Sayerus of Sutton, supposed Saxon ancestor of the Suttons of Dudley. Beaumont is flanked on the pedigree by Sayerus de Quency, earl of Winchester and the husband of Beaumont’s grand-daughter, Margaret, and Geoffrey Pagnell, Beaumont’s brother, described as earl of Somery in the right of his wife.Footnote 125 The controversies surrounding the attempts of the Dudleys to connect Sir Richard Sutton with ‘Sayerus, Lord Sutton of Holderness’ were long-running and it seems as if this was a connection that the Dudleys struggled to make stick.Footnote 126 However, this controversy has obscured the Dudleys’ attempt to find a link between the Sutton barony and the earldom of Leicester that lead them to the Saxon earldom of Mercia.

During the 1575 festivities to mark Elizabeth’s visit to Kenilworth, the Saxon kingdom of Mercia was used as a metaphor for the Midlands and the feast of the Mercian king, Kenelm, alleged builder of Kenilworth was celebrated during the queen’s stay.Footnote 127 In his account of the festivities, Robert Langham described the Midlands as ‘this Marchland that stories called Mercia […] the fourth of the seven kingdoms that the Saxons had’ and listed the shires that formed it as Gloucester, Warwick, Worcester, Chester, Derby and Stafford as well as ‘Hereford, Oxford, Buckingham, Hertford, Huntingdon, half of Bedford, Northampton, part of Leicester and also Lincoln’.Footnote 128 Whatever the controversies surrounding the publication of Langham’s Letter, it is clear that it circulated widely in print and manuscript.Footnote 129 The concept of Mercia placed the Dudleys’ Midland territorial interests in an historic context and suggested that they were part of an ancient whole. In 1066, Edwin and Morcar, the sons of Algar of Mercia, had been the most powerful men in the Midlands.Footnote 130 Morcar was also the leading land-owner in Holderness, the region that the Dudleys claimed as the lordship of their alleged Saxon ancestor, Sayerus Sutton.Footnote 131 In 1071, Edwin and Morcar lost their estates after a failed rebellion against William the Conqueror which resulted in Edwin’s death and the captivity of Morcar.Footnote 132 A putative link between Edwin of Mercia and the first Beaumont earl of Warwick had been copied by Robert Glover in 1572, in which Edwin was shown as the first husband of Turchil’s supposed daughter, Margaret, prior to her marriage to Henry Beaumont.Footnote 133 This fictitious marriage did not resurface in other documents produced between 1572 and 1582 but the attempt to link the pre-Conquest earls of Mercia with the post-Conquest earls of Warwick and Leicester did, suggesting that the Mercian connection had become central to the Dudleys’ activities. Some of Edwin’s lands in the Midlands went to the Norman William Fitzansculf, ancestor of the Sutton lords of Dudley. In 1086, Fitzansculf held Birmingham, Edgbaston and manors in Aston including Aston itself, Erdington, Witton, Handsworth and Perry and Little Barr.Footnote 134 Other Aston manors held by Fitzansculf’s descendants included Bordesley, Little Bromwich, Duddeston, Saltley and Nechells. In the 1570s, Castle Bromwich, Water Orton, Saltley, Duddeston and Bordesley were owned by Arden and it was mills in Duddeston and Saltley that were the focus of the dispute between Arden and Holte.Footnote 135

In 1578/9, Robert Glover worked at Arden’s home in Warwickshire, producing ‘something like an Arden cartulary’.Footnote 136 Glover’s interest in Arden’s charters has been seen as purely genealogical even though it is clear that the cartulary did not contain the usual materials needed for a pedigree.Footnote 137 Sixty-one charters were transcribed and over twenty-five seals were copied. The charters copied show the same connections again and again and those selected all date from the twelfth to the mid-fifteenth centuries. Most of the documents referred to grants or indentures relating to the Arden estate at Pedimore, Minworth and Curdworth and where no date was given, this was noted by Glover. The significance of Arden’s ancestry is shown by the inclusion of Turchil’s descendants from the time of William the Conqueror to around 1230.Footnote 138 In the same notebook, Glover included copies of charters concerning the Pagnells, seen as a link between the Somery and Beaumont families, as well as pre-Conquest charters and Bede’s list of Saxon kings.Footnote 139 He also noted the difference in status between the post-Conquest earls of Warwick and the Saxon lords of Warwick in a list in which Turchil is shown as a baron and the Beaumonts (Newburgh) as the first earls.Footnote 140 This contradicted the pedigrees prepared for the earl of Leicester in the early 1570s in which Turchil was described as earl of Warwick at the time of the Conquest, a change that suggests Arden and Glover were prepared to challenge the earlier version of the earldom’s descent.

In 1581, Robert Glover exhaustively traced the Dudley Sutton descent, not as part of a new genealogy but as a detailed investigation into that already proclaimed in the mid-1570s.Footnote 141 Across fifty folios, Glover outlined the Sutton descent and its connection to families including Somery, Pagnell and Malpas, all of whose arms were included in those of the Dudleys. Glover also investigated the links between the Sutton barony and the Beaumont earls of Leicester and the connection between the Leicester earldom and the Saxon earldom of Mercia.Footnote 142 The Mercian descent was shown from Leofric, ‘earl of Leicester in the time of King Ethelbald of Mercia’, through to Leofric, husband of Godiva, and ended with their grandson, Edwin, described as earl of Leicester and duke of Mercia at the time of the conquest.Footnote 143 A link between Edwin’s descendants and the Beaumonts was provided by Robert, third earl of Leicester (Blanchemains) and his wife, Petronella de Grandmesnil, generally if incorrectly depicted as the daughter of the Warwickshire land-owner, Hugh de Grandmesnil.Footnote 144 Petronella and Robert were the parents of Margaret, co-heir of her brother, Robert (d. 1204) and wife of Sayer de Quincy, earl of Winchester.Footnote 145 Although the tenure and division of the Leicester earldom after 1204 became particularly complicated, Sayer and Margaret held at least half of the Leicester inheritance.Footnote 146 Their son, Roger/Robert (Glover used both names) married Hawise, the great-great-grand-daughter of Edwin of Mercia’s alleged sister and co-heir, Lucy.Footnote 147 The descent produced in 1573 had already claimed Margaret as the ancestor of Robert Dudley. The marriage of Hawise and Roger/Robert therefore connected the descendants of Edwin of Mercia with those of the Beaumont earls of Leicester.Footnote 148 If the earls of Mercia were also earls of Leicester and if the Dudleys were descended from the Beaumonts—as already claimed in 1573—then the Dudleys would be able to assert their overlordship not only over Arden through Turchil’s subjection to the earls of Mercia but over all those manors which had belonged to Edwin of Mercia but had not become part of the patrimony of the earldom of Warwick.

In the same year, Robert Cooke finished the pedigree now at Longleat which opens with Guy of Warwick.Footnote 149 This restated the Dudleys’ ancestral connection to Guy through Turchil and showed Guy with the Beaumont shield chequy or et azure a chevron ermine as well as the emblem of the bear and ragged staff most closely associated with the Beauchamps and widely used by the Dudleys. However, this did not mark the end of Arden’s challenge to the Dudley appropriation of Turchil and he was prepared to press his case.Footnote 150 In the early 1580s, Robert Glover prepared an Arden pedigree, apparently in collaboration with Robert Cooke.Footnote 151 This document, never fully finished, is also missing text from the end of the document, meaning that the exact date is unknown. Fortunately enough remains for it to be clear that the pedigree was made by at Edward Arden’s request in order to provide an authoritative record of the Arden descent.Footnote 152 This pedigree for Arden showed Turchil and his father Alwin as lords of Warwick rather than earls. Alwin was shown with the Beaumont shield descending from Guy of Warwick on the Rous rolls and assigned to Guy and Turchil on the earlier Cooke pedigrees, making it clear that Arden was contesting the descent being put forward by the Dudleys (Figure 6a & Figure 6b).

Figure 6a College of Arms, MS 3/44 (detail) . Pedigree prepared by Robert Glover for Edward Arden, c. 1581–3. © College of Arms. Reproduced by permission of the Kings, Heralds and Pursuivants of Arms.

Figure 6b College of Arms, MS 3/44 (detail) . Alwin with the arms assigned to Guy of Warwick and the Beaumont earls on pedigree prepared for Edward Arden by Robert Glover. © College of Arms. Reproduced by permission of the Kings, Heralds and Pursuivants of Arms.

As Davies put it, ‘to challenge the authenticity and the exclusivity of a family’s coat of arms was […] to impugn its honour in the most fundamental fashion’.Footnote 153 Chequy or et azure a chevron ermine was shown descending to the Beaumonts through their alliance with Turchil’s supposed daughter, Margaret. For Arden to commission a document that assigned the arms of the earldom of Warwick to his ancestors was an unmistakeable challenge. This was an extraordinary document to produce, given that it contradicted the whole edifice of the connection between the post-Conquest earldom of Warwick and Guy. One fictitious ancestor—Margaret, daughter of Turchil—became the means to challenge the fictitious descent of the Beauchamp earls of Warwick from Guy.

To dismiss such manuscripts as Elizabethan hyperbole is to miss the point. Firstly, Margaret’s position as Turchil’s daughter was widely accepted, including by the scholarly Glover. Secondly, although Arden and Leicester were stretching connections to breaking point, we cannot assume that they acted in bad faith. Lineage was the primary factor in the transmission of land and status for centuries before their dispute, and remains a significant factor in a great many societies, including our own. The resort to lineage of Arden and Leicester grew out of the pressures created by competing elites but the Elizabethans did not invent the genealogical practices that went with these circumstances, they simply responded to new pressures by refining them, a response that has been identified as an obsession with genealogy. The Arden arms drawn by Glover at the end of the roll suggests that Arden was willing to give up fess chequy or et azure in favour of fess cross compony or et azure in support of his pedigree as a ‘true’ representation of the descent of the Arden family from Alwin and Turchil.Footnote 154

The success of Arden and his friends in sowing doubts about the Dudleys’ claim to nobility can be seen in the response of the Dudley camp. This has particular consequences for our understanding of Philip Sidney’s Defense of Leicester, described by Adams as ‘a near-hysterical reaction’.Footnote 155 It was also the only one of Sidney’s works apparently written for printing, a detail that suggests the widespread damage that attacks on the Dudleys’ origins had caused.Footnote 156 Three contemporary versions of the Defense survive, including Sidney’s original draft.Footnote 157 Although the only surviving manuscript copy with a date is dated 1582 (that in the Bibliothèque Nationale, Paris), this is believed to be a mistake, following the position taken by Katherine Duncan-Jones and Jan van Dorsten in the early 1970s.Footnote 158 The basis for this assumption lies in the belief that the Defense is a response to Leicester’s Commonwealth, understandable given that the first line of the Defense refers to ‘a book in form of dialogue to the defaming of the earl of Leicester’.Footnote 159 As Leicester’s Commonwealth has been reliably dated to summer 1584, so it has followed that Sidney’s Defense must have been composed shortly afterwards, and this has remained the sole basis for the dismissal of the date on the document in Paris. Nevertheless, the Defense has always been a puzzle for scholars, who have noted that it serves as a defence of the Dudley lineage that is barely attacked in the Commonwealth. Duncan-Jones and van Dorsten described it as ‘totally inadequate’ as a reponse to the Commonwealth, a view summarised by Dwight Peck as ‘The customary appraisal [that] argues that Sir Philip unwisely shifts his defence from the moral allegations to the very minor problem of Leicester’s, and Sidney’s own, ancestry’.Footnote 160 Peck has also noted that the motivation for the Defense – the attacks on the Dudley claim to gentility – and the accusation that Lord Hastings murdered the sons of Edward IV, are not actually in Leicester’s Commonwealth.Footnote 161

Either Sidney was not paying attention or the Defense is not a response to the Commonwealth, or at least not the version that was published in 1584. The possible existence of earlier drafts of the Commonwealth has been known for some time, although some claims have been given short shrift.Footnote 162 Nevertheless, manuscripts and books defaming the earl of Leicester were in circulation during the early 1580s and some of these influenced the work published in 1584. When Leicester’s Commonwealth did appear, Sir Francis Walsingham stated that he had heard of plans for such a book a few years earlier.Footnote 163 This has been treated with varying degrees of interest by historians but a letter written by William Herle to Lord Burghley in late 1583 confirms this. In December 1583 the priest, Hugh Hall, was in custody over his role in plotting the alleged assassination of the queen alongside Edward Arden and his son-in-law, John Somerville.Footnote 164 Hall was known to the Elizabethan regime and Herle reminded Burghley that the informant John Gilpin had come across Hall in Rouen in 1582, where he was smuggling books which described ‘the nobilyte, Cowncellors, & others well affected to God & our Sovereigne, in the sclanderest maner & most reprochefull that might be, onlye the Erlle of Sussex & som others were reverentlye spoken of’.Footnote 165 These works, referred to as ‘Hydes bookes’, confirm that seditious books about Elizabeth’s councillors were being printed at the same time that rumours of an early draft of the Commonwealth reached Walsingham.Footnote 166 Given that Arden knew both Robert Persons and other candidates such as William Tresham, the rather circular debate over the authorship of Leicester’s Commonwealth is less relevant in this context than the likely existence of earlier drafts that may have contained a much more detailed attack on the social origins of the Dudleys.Footnote 167 Nevertheless, Hall’s presence in Rouen, the location of Persons’ press, makes it possible that Hall, who had been lodging with Arden and his friends on and off for fourteen years, had a connection with Persons, who had stayed with Arden in the early years of the Jesuit mission.Footnote 168 Hugh Hall was only part of the traffic between England and cities including Rouen, Antwerp, St. Omer, Paris and Rome in the early 1580s. As well as William Tresham, other travellers connected to Arden included his nephews, Thomas and Francis Throckmorton, and Elizabeth Somerville, sister to Arden’s son-in-law, who was later arrested alongside her brother and accused of distributing seditious books.Footnote 169 In February 1582, Sidney and Leicester travelled from England to Antwerp, a major centre for the European book trade, as part of the entourage accompanying the duke of Anjou.Footnote 170

Rather than Sidney, one of the sixteenth century’s finest writers, writing a mis-directed, ill-conceived response to Leicester’s Commonwealth that contained references to things that were not even in it, it is more likely that in the early 1580s Sidney had seen a written attack on Leicester that required exactly the kind of response that is the Defense. Sidney’s emphasis on the Dudley connection to the barony of Sutton corresponds to the focus of Cooke’s pedigree from the mid-1570s and Glover’s research in 1581, as well as the rumours later remembered by Sampson Erdeswick. The bear and ragged staff was the emblem most closely associated with the Dudleys but this was a badge and not a coat of arms. The Dudley arms followed the common practice of placing the house from which nobility was derived in the top right-hand corner if holding the shield (dexter chief).Footnote 171 This position was generally occupied by the lion rampant of the Suttons.Footnote 172 To deny the Dudley descent from the Suttons of Dudley was a repudiation of their claim to nobility that left them without lineage and was therefore a matter of huge importance that they needed to contest at all costs. Previous Dudley attempts to dispel these rumours are implied in the Defense, given that Sidney wrote: ‘alas good railer, you saw the proofs were clear, and therefore even for honesty sake were contented to omit them’.Footnote 173 Sidney’s intention to print the Defense shows how widespread such rumours had become and how clearly the Dudleys and their friends understood that silence was inadequate as a response. This was explicitly addressed by Sidney in his justification for the piece, in which he explained, ‘because that thou, the writer hereof [of the libel] dost most falsely lay want of gentry to my dead ancestors, I have to the world thought good to say a little’.Footnote 174 In 1582, the year Robert Glover dedicated a book on disputed noble descents to the earl of Leicester and probably prepared Arden’s pedigree, the year of renewed conflict between the Dudleys and the earl of Sussex, who had been calling Leicester an upstart since the early 1560s, attacking the Dudleys’ lineage was an active political strategy. In 1582, the only year found on any of the surviving versions of the Defense, a defence of the Dudleys’ ancestry was exactly what was called for. As part of the response to attacks on the Dudleys’ ancestry that may have included Harvey’s Gratulationes and almost certainly included Spenser’s lost work, the Stemmata Dudleiana, Sidney’s Defense not only makes sense, it shows how wounding the attacks were.Footnote 175

However, events may have overtaken plans for the Defense to be printed. In early November 1583 Edward Arden was arrested and accused of treason. In summer 1584 William Allen wrote in A Defense of English Catholics that Arden was brought down by ‘the malice of his great and potent professed enemy that many years hath sought his ruin’.Footnote 176 Arden’s wider connections were hinted at in Leicester’s Commonwealth, which saw his fall as part of a plot to bring down Sir Christopher Hatton.Footnote 177 The judicial process that saw Edward Arden and his son-in-law, John Somerville, accused, indicted, tried and killed for treason, lasted a little over seven weeks. Arden’s arrest and execution was commented upon by Richard Barret, Robert Persons, Robert Southwell, Juan Bautista de Tassis in Paris and Mendoza, the Spanish ambassador in London, several of whom referred to the framing of Arden and the involvement of Leicester.Footnote 178 Arden’s estate was forfeit to the Crown and one of the last Saxon estates in England, first broken up by the Beaumont earls of Warwick and Leicester after the Conquest, was finally brought down by the Dudley earls of Warwick and Leicester five hundred years later. Seventy years after the death of Edward Arden, in the political landscape of republican England, Sir William Dugdale concluded in the Antiquities of Warwickshire that ‘these hereditary vicecomites [Alwin and Turchil] were immediately Officers to the King and not to the Earles of Mercia’.Footnote 179

By challenging Leicester’s ancestral claims, Edward Arden challenged the validity of the Dudley lordship in Warwickshire and by implication, in the country. The Dudley attempt to impose their authority in Warwickshire was not straightforward and the Black Book recounts a telling scene in 1576 when their main officer in the county, Sir John Hubaud, lost his temper with the burgesses of Warwick, angrily noting that when Sir George Throckmorton was around, they did what they were told.Footnote 180 The pressure put on the Dudleys to prove their right to power – the sort that depended on a mythical Saxon past and the kind of ancient nobility ‘whereby men’s affections are greatly moved’, as the authors of the Commonwealth put it – should not be seen as resulting in antiquarian business with crests and badges and pedigree rolls and ostentatious showing-off by the earl of Leicester, it should be seen as resulting in political behaviour essential to the establishment of their position.Footnote 181 The Dudleys had titles, wealth, land and the favour of the queen but their lineage made them vulnerable in the eyes of those who were keen to show that they represented the overthrow of civil society. Like the Protestant church depicted by Richard Bristow in his 1574 treatise, the Dudleys were deemed to lack ‘proof of lawful and lineal descent’.Footnote 182

Edward Arden was part of a network that was not necessarily united but which was, beyond a shadow of doubt, political. In 1580, Thomas Throckmorton and Ralph Sheldon were imprisoned in the government’s round-up of leading Catholics.Footnote 183 The following year, so were Sir Thomas Tresham and Sir William Catesby as part of the Elizabethan regime’s pursuit of Edmund Campion, one of the seminal political events of Elizabeth’s reign.Footnote 184 Although the contacts of the Catholic and conservative gentry are generally considered to be with nobility who were ‘peripheral to the Elizabethan establishment’, it is possible that it was their continuing connections within the establishment that made some networks such a concern.Footnote 185 The dichotomy of Protestants and Catholics during the 1570s has served as a distraction from the ways in which Catholics like Edward Arden still functioned within a broad base of the politically active, a reflection of the patterns of behaviour identified in social relations.Footnote 186 A historiography of consensus among those closest to Elizabeth that requires that other interests were peripheral makes it difficult to understand the connections between the Catholic gentry and those described as ‘Richard II’s men’ by Sir Francis Knollys in January 1578.Footnote 187 This group, tentatively identified as including Sir James Croft, the earl of Sussex, Lord Henry Howard, Lord Paget, Charles Arundel, Sir Edward Stafford and possibly Sir Christopher Hatton, amounts to more than the ‘smooth-tongued flatterers’ described by Collinson, given that three of these men were privy councillors.Footnote 188 Moreover, a more detailed picture of political relationships during the 1570s would allow us to integrate these into events such as the proposed marriage of Elizabeth to the duc d’Anjou. As recent research has shown, the entertainment given at New Hall by the earl of Sussex in 1579 allowed Catholic and conservative nobility and gentry to show their support for a match strongly opposed by committed Protestants like the Dudleys.Footnote 189 Both the earl of Sussex and Sir Christopher Hatton acted as points of contact for those hostile to the political aims of the Dudleys and their associates. Sir Christopher Hatton, whose Catholic step-father, Richard Newport, was Henry Ferrers’ great-uncle and a Warwickshire magistrate between 1547 and 1562, was particularly close to Edward Arden and his kinship network.Footnote 190 Initially at least, Arden’s opposition to the earl of Leicester was not irrationally suicidal but part of an environment in which Catholics were neither excluded from court politics nor circles close to the queen.

Arden’s decade-long challenge to the Dudleys was part of an extremely tense political atmosphere. The Dudleys’ attempt to counter Arden through genealogy and legal pressure shows how keen they were to avoid action that could be depicted as tyrannical. This did not work, as the production of Leicester’s Commonwealth testifies. However, this indicates the scale of their task as much as their inclination to ride roughshod over Catholic interests. In the Midlands, the Dudleys were instrumental in disrupting the power of the resourceful and well-connected Catholic Throckmorton network. Why this was so is better explored through the Dudleys’ role in Elizabeth’s government rather than the alleged dastardliness of the earl of Leicester. The Dudley acquisition of titles and land was almost entirely dependent on the queen.Footnote 191 In these circumstances, the creation of Ambrose Dudley as earl of Warwick, and Robert Dudley as earl of Leicester, can be seen as political appointments that they might not have sought solely for purposes of personal gain. The re-establishment of the Dudleys as the dominant magnates in the Midlands during Elizabeth’s reign suggests that there was the need for a sole political authority in the region that probably had less to do with the continued practise of Catholicism than the issue of the succession, a question with which Arden and his connections were deeply concerned.Footnote 192 Moreover, the loyalty to Elizabeth of Arden and his friends and relations was disputable and Arden willingly sheltered Robert Persons and the Marian priest Hugh Hall. The Dudleys enabled Elizabeth to exert control over the Midlands while allowing her to deny the charge that she was alienating the interests of specific groups. As Leicester wrote to Lord Burghley in November 1579, ‘Your lordship is a witness I trust that in all her services I have been a direct servant unto her, her state and crown, that I have not more sought my own particular profit than her honour’.Footnote 193 Leicester’s posthumous reputation shows that few have taken him at his word. At the same time, the historiography of Protestantism has masked the political activities of the Catholic and conservative nobility and gentry, depoliticising activities such as genealogy along the way. The connection between denigration of the Dudleys’ origins and the agenda of established political families is one way of re-integrating Catholic and conservative interests into Elizabethan politics as well as addressing Adams’s recent observation that historians ‘have failed to appreciate that “the ancient nobility” was one of the major political issues of the reign’.Footnote 194 Those who identified themselves with or among ‘the ancient’ attacked the Dudley ancestry as a deliberate political strategy. At a time of pan-European religious conflict, these were the politics of highly-educated elite groups in which confessional, political and territorial disputes were contested through powerful connections to family, history and land.

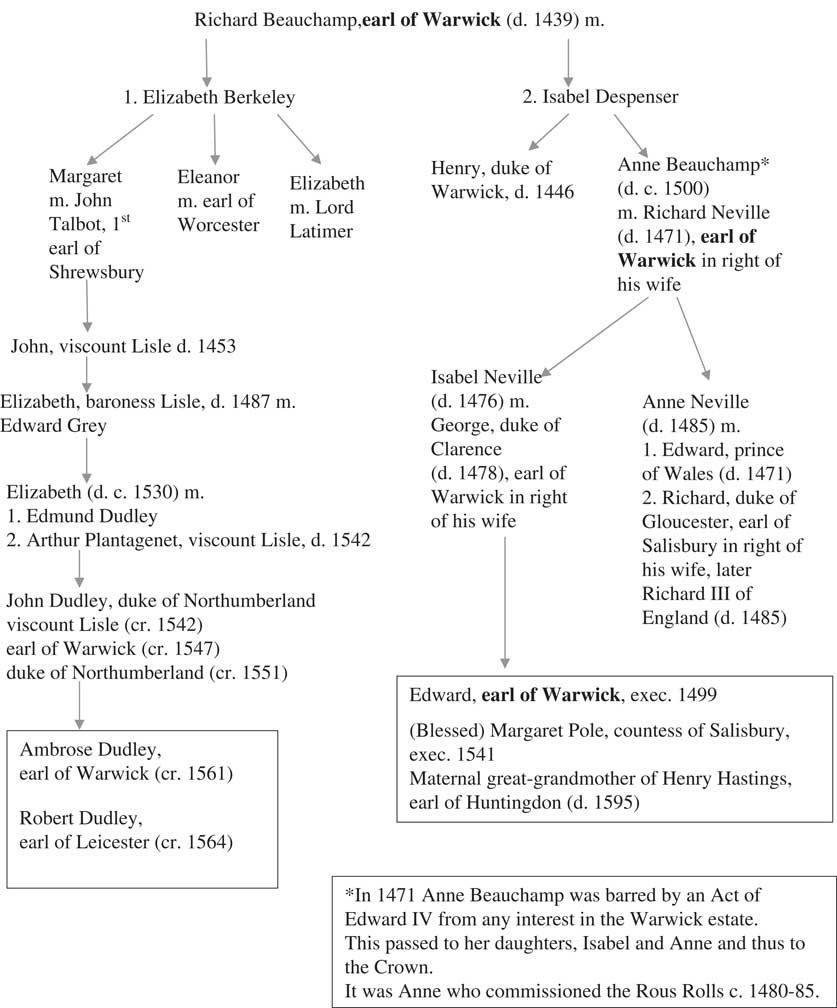

Appendix I

Descent of earldom of Warwick from Richard Beauchamp, earl of Warwick, d. 1439

Appendix II

Map of north Warwickshire and part of Staffordshire

Local residence of figures referred to in the narrative:

Appendix III

Simplified descent of the Arden family and the earls of Warwick from Alwin and Turchil as used in the dispute between Edward Arden and the Dudleys

Appendix IV

MS sources connected to the descent of the earls of Warwick, the Dudley family and the Arden family made or used by the heralds, 1572–1582 (*current attribution)

Other useful documents:

Appendix V

University of Pennsylvania State, MS Codex 1070

http://openn.library.upenn.edu/Data/PennManuscripts/html/mscodex1070.html

fol. 1v

The genelogies of the Erles of Lecestre & Chester

wherin is brifely shewed som part of their deedes

and actes with the tyme of their raignes in

their Erldoms and in what order the saide

Erldoms did rightfully descend to the crowne, and

in the same is also conteyned a lineall descent

shewing how the right honorable Robert Erle of

Lecestre and Baron of Denbigh knight of ye Garter

and Chamberlen of Chester is trewly descendid of

Margaret second sister and one of the heires of

Robert fitz Pernell the fifte Erle of Lecestre and

of Maude and Agnes the first and third doughters

to Hugh Kenelock the fifte Erle of Chester, sisters

and coheirs to Randolf Blondevile the sixt Erle of

Chester. Note that the lynes and descent come

from those rondells in the margent which be

stayed by two leaves and the other rondells that

are stayde but by one leafe are the colaterall

children

Appendix VI

College of Arms, MS Num. Sch. 3/44: Final inscription on pedigree of Edward Arden attributed to Robert Cooke and Robert Glover, c. 1581–3, written by Robert Glover

This pedigree hath bene written, collected, gathered and for memory in this

order sette forthe by Robert Cooke esquire als Clarenceux principall

herald and king of Armes of the South partes of this realm of England and

Somersett herald of Armes at the request of Edward Arden of Park hall

in the county of Warwick esquire […] to the truth of the records in the

office of Armes and by view of […] other matters of great

[…] and antiquity remayning in the [...] Edward Arden

esquire. In witness whereof […] armes and

somersett herald have hereby […] day of ffebruary

[…] in the yere of our lord god and of our

most gracious sovereign Lady […]