The bishop’s letter

On 16 August 1615, Bishop James wrote a letter to the archbishop of Canterbury, George Abbot (1562–1633), in which he discussed a rapidly escalating Catholic crisis.Footnote 1 At least since mid-July, James’ spy, Christopher Newkirk of Gateshead, a surgeon of Polish origin, had been infiltrating a well-organized network of priests and lay Catholics in the north-eastern counties, including Yorkshire, who were apparently devising a new gunpowder plot, an attack on the king and his family ten years after the failed attempt of 5 November 1605.Footnote 2 On 16 August, however, Bishop James was yet unaware of the full extent of the conspiracy which his spy had been uncovering. He so far remained uninformed of the three engines allegedly built by Ambrogio Spinola’s engineer Alexander Malatesta somewhere in the hills of Cardiganshire, nor of the level of logistical sophistication of the plotters, who, in Newkirk’s words, ‘haue almost in euerye Creake, or haven Towne, some Vessils’.Footnote 3

Only a week later, James reported back to the archbishop yet again. This time, amazed by the scale of the unravelling plot, he wondered whether the Privy Council was already aware of its pending danger for the state and had taken the necessary measures to prevent the catastrophe.Footnote 4 Indeed, the most striking feature of the available state papers surrounding the correspondence is the absence of any immediate interest in James’ reports. George Abbot shrewdly communicated Newkirk’s intelligence to the secretary of state Ralph Winwood on 17 August, but on the whole, the Council appears not to have shared William James’ anxieties.Footnote 5 The impression we get from the available documents, and the affair in general, seems to confirm James’ suspicions that the London government had already been aware of the scheme from other sources. In any case, the conspirators experienced setbacks and the attack ultimately never took place.Footnote 6

Although national concerns already feature prominently in Bishop James’ deliberations from 16 August – he comments on the rumours of a Catholic invasion and wonders what Winter and Digby, two Worcestershire men, are doing in the northern parts – he seemed to be, for the time being, more alarmed by the local repercussions of the unprecedented ‘flockinges of Priestes […] in Newcastle, a Haven, & walled Towne, wherein there was within thes fewe yeares not one Recusant’.Footnote 7 James’ formulations seem hyperbolic, contrived to persuade the head of the Church of England that the situation in the North is dire, that the king ‘must be pleased (if he will regarde his owne safetye, and the safetie of his kingdomes) to alter this lenitye towardes the Priestes, who (whatsoeuer they, or their fauourers enforme his Maiestie) thirst after nothing but bloode’.Footnote 8 However visceral James’ rhetoric may sound, his language remains precise. He is careful not to dissociate the rise of recusancy from the missionary activity of the seminarists, nor to mislabel Catholics in general for recusants.

Since 1583, when Queen Elizabeth I granted the ninety-nine-year Grand Lease of the immensely profitable coal mines in Gateshead and Whickham to then mayor Henry Anderson and his associate, alderman William Selby, Newcastle-upon-Tyne’s civic institutions had been overwhelmingly in the hands of the influential coal-merchant families, which were, after 1600, newly incorporated as the Company of Hostmen.Footnote 9 Many of these families, such as the Selbys, Chapmans, Jenisons, Tempests, Riddells, and Hodgsons, had strong Catholic leanings and secretly supported the Catholic community, although, due to local political and social legacies, they tended to conform, cooperate with authorities, and remain staunchly loyal.Footnote 10 William James, who had been working in the diocese since 1596 (first as dean, and then, from 1606, as bishop), was more than aware of the supposed religious backwardness of the North East.Footnote 11 He knew how widespread church-papistry was in the diocese and that this semi-conforming Catholicism and specific local attitudes towards state policies dangerously thwarted any efforts by the diocesan authorities to bring Newcastle to genuine conformity.Footnote 12

After James I’s accession, the enthusiastic support for the Stuart dynasty among the northern Catholic gentry of the Neville circle complicated matters even further. Particularly in the North, ‘[p]apistry was regarded as a threat precisely because of its malleability, its capacity to adapt and its readiness to integrate’.Footnote 13 Therefore, notwithstanding the bishop Toby Matthew’s recusancy report from January 1596, which lists only four recusants in the city parishes, Newcastle had by then already developed into an auspicious Catholic centre.Footnote 14 Thereafter, recusancy grew.Footnote 15

Yet micro-variations in its figures during the eleven years of William James’ incumbency in the diocese of Durham are important for our subsequent discussion. In the palatinate of Durham alone, which at the time included substantial lands in Northumberland, the number of convicted recusants decreased from around 450 individuals in 1608 to merely 289 in 1613.Footnote 16 However, recusancy gained ground again in the following years. Around 1615, there were 432 convicted recusants in Palatinate alone.Footnote 17 Bishop James clearly and openly articulated these developments in June 1616 in a letter to Ralph Winwood. Speaking with the whole diocese of Durham in mind, James claimed that ten years earlier, at the start of his episcopacy, the number of recusants was around 700.Footnote 18 This number had been after ‘4 or 5 yeares by the Ecclesiasticall Commission, & other Meanes, brought to 400’, but ‘lately encreased againe to the number of 500 & odd’.Footnote 19 The latest number James is referring to must be from 1613, since it had been communicated to the king at the last parliament, in spring 1614.Footnote 20 However, a new ‘particular & true Certificate of all the Recusantes within this Diocese’ was soon to be prepared, following the bishop’s three-week visitation of the diocese, so James was not yet sure whether the figure had increased or diminished.

The numbers had in fact increased. In March 1616, Henry Anderson, at the time sheriff of Northumberland, already reported to the Council that there were 507 popish recusants and 432 non-communicants in Northumberland alone.Footnote 21 It is highly probable that the Lambeth Palace Library recusancy report provisionally dated to c. 1615 is actually based on James’ 1616 diocesan visitation mentioned in his letter to Winwood. If that is the case, then recusancy numbers in the diocese of Durham had grown drastically, from 519 convicted recusants in 1613 to almost 1,000 in 1616.

Thriving evangelization and revived Catholic confidence in Durham and the English Middle Shires can generally be ascribed to the increased influence of the pro-Catholic Howards after the death of George Home, Earl of Dunbar, the chief border commissioner, in January 1611, and Robert Cecil, Dunbar’s vigorous supporter, in May 1612.Footnote 22 The revival of factionalism in the region and increasing religious tensions may have contributed to the concurrent growth of recusancy in Newcastle.Footnote 23 By the mid-1610s, several recusant strongholds in the Tyneside region provided indispensable support for seminary priests working in Newcastle. The most significant were the residences of Sir Robert Hodgson at Hebburn and Dorothy Lawson, first at Heaton and sometime after 1613 at Saint Anthony’s, on the north bank of the river Tyne.Footnote 24 Although both houses, often working in tandem, were notorious for harbouring priests and recusants, the authorities were unable to arrest the ringleaders and suppress their subversive enterprise because they were tolerated by the Newcastle elite.Footnote 25

The rise of nonconformity and increased activity of priests indicate that the Catholic population throughout the diocese felt confident enough to step into recusancy. It is during this period that we first hear of Robert and Anne Hindmers. In August 1615, in order to illustrate to the archbishop of Canterbury the graveness of recent developments, Bishop James intriguingly chose to expand on an unusual account of persecution:

Since that time, my Intelligencer hath bene with me, & deliuered to me this, which I send your Grace herein enclosed wherein I use his owne wordes. He maketh mention of a dauncer, a poore mans sonne, borne in this Citie, yet proude, & insolent, and lately made a Recusant, and by his daunceing crept into manie houses, and his wife a younge woman (being both Recusants) haue done much harme and might haue done more. At his first comming before vs, I vsed him (knowinge his frendes to be verie poore, & needie, & his mother blinde) in the best sorte I coulde, and he refuseing all conference; as also to take the oathe of Allegiannce; wee committed him to Prison the third of this instant, where he hath remained, & yet doth. Vpon Consideracion of the enformacion herein enclosed, I willed the Gaoler, to offer him from me, that if he would be content to be instructed by anie learned man, that he might haue his libertie, and time to thinke of the oathe of Allegiannce; But he grewe so resolute as that he woulde accept of neither, whereby your Grace maie see what hopes, & encouragement they haue.Footnote 26

The letter, which is of considerable importance for dance history, not least because the dancer’s wife had clearly travelled and quite possibly danced alongside her husband, has not yet been considered by performance experts.Footnote 27 The letter is not explicitly acknowledging the dancing abilities of Hindmers’ wife, but taking into account similar records of itinerant performers from the period, in which professional husbands were accompanied by their lay wives, who nevertheless contribute to the performance in some capacity, allows us to reasonably speculate about the active involvement of the dancer’s wife.Footnote 28 Moreover, although the description offers scant details of the couple’s itinerant venture, their activities, including dance, seem to be linked in the bishop’s mind to confessional issues and Catholic evangelization.

James uses the dancer’s case to articulate the current concerns within the diocese and convey his own political appeal. The bishop’s narrative challenges not only the expected social and economic modus vivendi of the post-Reformation Catholic community, but, more importantly, defies the government strategies used to enforce religious conformity: pecuniary punishments for church non-attendance do not necessarily prevent those without land or goods from recusancy. The dancer thus becomes a symptom of a wider disease. For James, he encapsulates the new “papist” zeal made fresh by numerous illegal priests, a zeal which, quite unlike what leaders of the national Church would expect, is receiving its impetus from the lower orders of society. However, the tenor of the exemplum is not only in illustrating the importance of seminarists’ ministry, which can successfully exhort even poor dancers with blind mothers to stubbornly keep their apostasy, but also that “popish seducers” can assume the most unusual shapes: that of itinerant dancers.

Robert and Anne Hindmers

Legally speaking, the dancer was incarcerated for his recusancy and, more importantly, for refusing to take the controversial oath of allegiance.Footnote 29 The oath was evidently tendered to him by the bishop and not the two justices, since William James is quite precise in describing his personal involvement in the legal process. More details on the case survive in the only extant Jacobean court book of the Durham High Commission, which covers the period from 1614 until 1617.Footnote 30 Often written in a small, barely legible secretary hand and mostly in English, the ex officio correction cases are interspersed between long lists of recusants, the majority being gentry, for whom attachments, i.e. arrest warrants, have been issued by the commission. The sheriffs’ success in apprehending recusants was poor and on each subsequent session of the court, which usually occurred once every month, the warrants for the great majority of the accused were reissued.

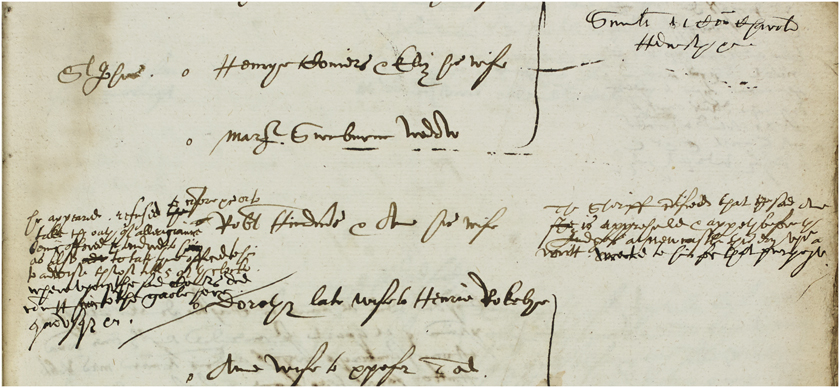

In his letter to the archbishop, James claims that he incarcerated the dancer on ‘the third of this instant’, i.e. 3 August 1615. The commission was indeed in session on that day, during which the sheriff of Newcastle, John Cook, ‘certyfied that none of the persons named in the said attachment could be found within his baliwick excepte Robert Hindmers & Anne his wife’.Footnote 31 There is no mention of Robert’s or Anne’s occupation, but the details found in the proceedings on the next folio match perfectly with the bishop’s narrative in the letter (fig. 1). ‘[H]e appeared’, the small writing next to Robert’s name affirms, and ‘refused to conform &c or to take the oath of alleagiance being offered to tendered to him as also to tak tyme offered to him to advise thereof till 5 of the clock’.Footnote 32 Since Robert refused to take the oath or be advised on it in a private conference, ‘the said Commissioners did committ him to the gaole’.Footnote 33 Anne did not appear at the Durham session together with her husband. She was instead, the sheriff reported, ‘apprehended & appeareth before the Judges at Newcastle this day’.Footnote 34

Figure 1 Durham High Commission court book, August 1615. Details on the incarceration of Robert and Anne Hindmers. Durham Cathedral Library, Durham, DCD/D/SJB/7, fo. 28r. By kind permission of the Chapter of Durham Cathedral.

Robert and Anne Hindmers were included in the commission’s recusant lists since May 1615; they were seized less than three months after the first warrant for their arrest had been written, which is unusually fast considering the generally poor rate of the sheriffs’ success. What happened afterwards remains a mystery. The Durham quarter sessions records are missing for the period between July 1615 and April 1616. It is very likely that during those Michaelmas or Epiphany sessions Hindmers appeared before the court again, swore the oath, and was subsequently released as the later sources seem to suggest.

What more can we learn about Hindmers’ life, dancing, and his role within the Catholic community? Following the bishop’s assertion that he was a poor man’s son, born in Durham, his family background can be pursued in parish registers. Robert, son of Richard Hindmers, was baptized on 24 January 1585 at St. Mary-le-Bow, North Bailey, Durham.Footnote 35 His father had married Jane less than three months before, on 4 October 1584 at St. Nicholas.Footnote 36 Sometime before 1589, when the death of Richard’s and Jane’s infant son (due to plague) is recorded, the family moved to or near Newcastle, to the parish of St. John the Baptist; perhaps in search of a better life in a city with a booming coal industry.Footnote 37 Tragedy soon struck the family again: on 11 April 1591 they had to bury Richard himself at St. John’s. For a family of insufficient means the death of a father was not only an emotional but also an economic blow; all the more so, if we consider Bishop James’ claim that Jane eventually turned blind. Nothing else is known for certain about Robert Hindmers’ youth. By May 1615, Robert and Anne’s religious non-conformity and vagrant lifestyle had already been noticed by church officials and on 23 May the first known warrant was issued for their arrest. The date of their marriage remains unknown. It is possible that the couple got married clandestinely, the Catholic rite perhaps conducted by William Southerne, a Newcastle-based missionary, who had returned to England in 1605, after finishing his studies at the Jesuit College in Polish-Lithuanian Vilnius and the English colleges at Douai and Valladolid.Footnote 38 In any case, Southerne was close to Robert Hindmers.

Christopher Newkirk’s memorials, copies of which were regularly attached to James’ correspondence with George Abbot, give substantial details of the Hindmers’ social milieu. On the evening of 7 August 1615 the priest William Southerne met with Newkirk at his house in Gateshead. The spy had recently returned from Durham and received the priest at 9 o’clock, offering him wine, pears, walnuts, and east country gingerbread, which sufficiently fuelled their conversation.Footnote 39 Intriguingly, the most pressing matter that evening was not the rumours of a foreign invasion, or logistics of the mission, but the dancer himself, imprisoned four days before the Gateshead meeting. Southerne was keen to learn about any further developments:

Then he asked me, if I had not heard of the prisoner, a dauncer (taken by the sheriffe and brought to Durham to take his oathe and confess the Supremacye of his Maiestie, which he denyed). I told him no. And further he said that the said dauncer had his maintenance from the Catholickes.Footnote 40

It is likely that the allowance Robert received from the Catholics was given to him in exchange for his itinerant activities, but we cannot be certain. Unfortunately, the priest also remains silent about who exactly supported him, although it is fair to assume that the dancer’s viaticum was administered to him through the hospitality of Catholic households and the funds raised by priests and the faithful.

This last speculation is substantiated on the subsequent page of Newkirk’s report. Although the spy’s narrative is emotionally detached and focused on factual details, it nevertheless conveys Southerne’s concern for Hindmers’ fortunes. He must have known the dancer very well and evidently trusted him. He tells Newkirk that ‘the dauncer now in prison, hath been a good member vnto vs, but he shall not want, for wee priestes gather for him’.Footnote 41 Southerne acknowledges Hindmers’ worth for the community and assures Newkirk that the dancer will not suffer deprivation in prison, but will be relieved by the funds collected on his behalf. Whether this collection is in some way related to the maintenance Hindmers had received before his imprisonment is unclear, but probable.

Prompted by the disagreeable state of the dancer, Newkirk suddenly feigns fear of similar imprisonment, to which Southerne offers a brisk and disparaging response:

Then I saide, how shall I doe, I am like to incurre such daunger. ffye fye, neuer take such care said he, yow are none of them that convert others, & yow are a straunger & nothing to loose but your goods, and if the bannishe yow, yow shall haue our lettres of preferment. If yow be imprisoned, yow shalbe relieued.Footnote 42

Although the priest assures the spy that he too will receive support from the community if the worst happens, Southerne nevertheless seems to be implying a distinction between Newkirk and Hindmers, who is, unlike the spy, a man ready to ‘convert others’.Footnote 43 However, the syntax of the passage is imprecise and Southerne may be referring to himself rather than the dancer. In any case, true conversion to Catholicism could only have been obtained through a sacramental confession conducted by a priest, although Hindmers could have somehow participated in greasing the wheels of conversion, possibly in tandem with Southerne himself, who was, after his martyrdom in 1618, particularly credited for his apostolate among the Tyneside poor.Footnote 44

The assistance offered to missionaries by lay commoners, which stretched from harbouring and escorting priests to acting as messengers, distributing Catholic books, and actively “seducing” their neighbours to Catholicism, was not uncommon in post-Reformation England.Footnote 45 John Parkinson of Knayton, North Yorkshire, was in 1595 ‘thought to be a conveyor of Seminaries from place to place’, while Lyonell Forster, a ‘malicious recusant’ and a yeoman of Rothbury in Northumberland, often travelled further north to ‘Balmebroughshire and Glendiall seeking to seduce others’.Footnote 46 George Swalwell of Wolviston, yeoman, was in 1634 accused by Durham High Commission ‘to have seduced some of his Majestie’s good subjects from their allegiance and obedience to his highness, and for teaching schollars without a licence, he being a recusant papist’.Footnote 47

As travelling Catholic commoners, the Hindmers were probably engaged in similar activities. We know that the couple worked for the seminary priests, were financially supported by the mission, and that their enterprise was, according to the bishop, harmful. What is particularly significant about the couple and makes their case unique is that they were known to practice dance; at least Robert was, for he is explicitly identified as a dancer by both Bishop James and William Southerne. Although the evidence about the exact role of dancing in the Hindmers’ itinerant venture is unclear, Robert’s alleged occupation should not be dismissed as a mere pretence.

In 1592, pursuivants John Worsley and William Newell reported that in visiting Mrs. Marchant’s house in Gloucestershire, they found ‘a very bad man, and by Report one that doth great [a word missing] in the contries for vnder the cowller of teching the childer mvssiket, it is thought that he doth teche them worse matters, for he is a notable Recwesant’.Footnote 48 Although Worsley and Newall are explicit in claiming that imparting musical skills to children was only a pretext, probably for Catholic catechizing, it would be wrong to assume an absolute disjunction between the teacher’s cover and his actual activities. In other words, teaching ‘worse matters’ most likely included practicing music.

Worsley and Newell claim that this Gloucestershire teacher had been previously arrested at Francis Yate’s house in Lyford, ‘when Camppan [Campion] was taken’.Footnote 49 Amongst those arrested with Edmund Campion was indeed a musician. On 14 August 1581, the privy councillors sent a letter to the vice-chancellor and the heads of colleges of the University of Oxford, demanding that they question three masters of arts and search the houses for suspected Catholics, for they were worried

that most of the Seminarie priestes which at this present disturbe this Churche haue ben heretofore Schollers of that vniuersitie & that they & likewise one Jacob a Musitian taken in Campions companie haue ben tolerated there manie yeres with out goinge to the Churche and receavinge of the Sacramentes.Footnote 50

Described as a “musician” rather than a “minstrel” and being active at Oxford, as the letter seems to imply, Jacob was almost certainly a formally trained occupational musician; most probably he was a student and a chorister at New College, Oxford, in the mid-1560s.Footnote 51 On 16 August 1581, John Jacob was committed to the Marshalsea, where he remained at least until 8 April 1584.Footnote 52 On 24 August 1582, he was found at Mass in Mr Parpoynt’s chamber in the same prison.Footnote 53 Being close to Campion, Jacob was also a friend of John Gerard, who visited him after his transfer to Bridewell prison.Footnote 54 Although Gerard provides a gruesome description of the musician, who was ‘wasted to the skeleton’, Jacob did not die in prison, as Caraman assumed.Footnote 55 He was released and at liberty for at least five years before he was once again imprisoned, this time in the Clink, on 21 January 1593, after being arrested in Mrs Machant’s house in Gloucestershire by Worsley and Newell.Footnote 56 On 17 April 1593, Jacob was examined and described as of Avill (near Dunster) in Somerset.Footnote 57 He sometimes owned a house in Oxfordshire, but the last five years he spent in Abingdon, London, the Stonor household near Henley, and at Mrs. Mercer’s.Footnote 58 Jacob was confident in his Catholicism; he declined a conference with a minister and refused to come to church. However, the more intriguing details are given in the summary of the examination, where, echoing the language of Worsley and Newell, the commission described Jacob as ‘a syngyng man’ and ‘a goar from one recusante’s houwse to another undar the collar to teche mewseke’.Footnote 59

Although Jacob seems to have been an Oxford-trained chorister, his teaching repertoire would probably not have been limited to sacred music. Popular music too played an important part in Catholic culture and evangelization. Emilie Murphy has demonstrated that English seminarians followed Jesuit missionary practices by ‘learning the tunes of the most popular songs in order to utilise them and disseminate Catholic adaptations to their melodies’.Footnote 60 For example, a tune, now lost, of the secular ballad ‘Dainty come thou to me’ was used to accompany a new sacred text of the ballad ‘Jesus come thou to me’.Footnote 61 Although we cannot be certain whether Jacob was indeed catechizing children by using such “converted” songs, it remains a real possibility, especially because he was associated with the Jesuit mission.

Conversely, neither the Hindmers’ case nor any other known example explicitly demonstrates that practicing dance by itself could have been an instrument for religious instruction. Although in certain contexts, dance could have been quite strongly associated with pre-Reformation culture, the links between dance and Catholic evangelization remain tenuous. The key evidence, which may suggest that the Hindmers did not use dancing merely as an outward appearance, is the fact that like John Jacob, Robert too was, as will be demonstrated, a professional: teaching fashionable dance was probably his main source of income. Undoubtedly, Robert’s occupation conveniently justified the couple’s peregrinations before the authorities; but the mission’s employment of a dancing master may also indicate the cultural significance of dance among Catholics in the North East.

A dancing master to the Howards

At present, only one of Robert Hindmers’ patrons can be identified: Lord William Howard of Naworth Castle near Brampton in Cumberland. Lord Howard was an avowed Catholic, a notable antiquarian, and the most powerful and influential landowner in the English borderlands.Footnote 62 Being a Catholic, William Howard was barred from holding a public office. But he nevertheless exerted considerable authority in the borderlands, particularly after 1614, when his conforming nephew Theophilus Howard de Walden became a commissioner and a co-lord lieutenant of the English Middle Shires.Footnote 63 Because he was a staunch loyalist and supporter of the oath of allegiance, he enjoyed the patronage of both James I and Charles I, who protected him from being prosecuted for recusancy.Footnote 64 Being a beneficiary of the sovereigns’ favour, Howard remained unimpeded in exercising his influence and in supporting individual Catholics in need, in spite of sporadic vicious attacks by northern Protestant officials.Footnote 65

Lord William Howard’s household accounts, which cover (albeit with considerable gaps) a period from 1612 until his death in 1640, demonstrate his family’s taste for dancing. Disbursements to Lady Elizabeth Dacre, Lord William’s wife, often include purchases of various necessities for their children and grandchildren, from luxurious clothing to toiletries and gambling money. On 1 August 1612 three pairs of ‘red dancing pumpes for the children’ were acquired for four shillings.Footnote 66 The flamboyant pumps were probably purchased for William and Elizabeth’s youngest daughter Mary and/or their oldest grandsons, William, son of Sir Philip Howard, and Thomas, son of Sir Henry Bedingfield, a Norfolk Catholic, and Elizabeth Howard.Footnote 67

Dancing education at Naworth was taken seriously. On 12 August 1613, the considerable amount of forty shillings was paid to one Robert ‘for teaching the gentlemen to daunce’.Footnote 68 After a substantial gap of six years, which is due to missing accounts, we find another payment made on 23 July 1619 ‘to mr Heymore for teaching to dance in part’.Footnote 69 “In part” must refer to partial payment. In autumn 1620, Lady Elizabeth visited Thornthwaite hall, a family residence in Westmorland, where between 31 October and 10 November a similar reward of 20s was given ‘to the dawncer’.Footnote 70 This could not have been a payment for a performance because the sum is simply too large. We only need to compare it with a reward given to anonymous players from the same period, who as a group had received merely half of the amount given to the dancer. The payment to the Thornthwaite dancer almost certainly represents the second part of the reward due to Mr Heymore in 1619, and must have been issued in exchange for dancing lessons.Footnote 71

The last dance-related entry in Lord William’s household books is the most fascinating of the set and sheds new light on all the previous expenses. On 22 August 1634 a payment of 40s was made to ‘Mr Robert Hymers for one Moneth Teachinge Mr William Howard and Mrs Elizabeth his Sister to daunce’.Footnote 72 It is worth pointing out that Douglas’ REED transcription errs in rendering Robert’s last name as “Hymes” instead of “Hymers”, although the same surname could at the time be spelled either way (fig. 2).Footnote 73 The scribe’s final “es” is normally very clear; the letters are neatly connected with either horizontal or slightly descending link.Footnote 74 However, in the case of Robert’s last name, where the double stemmed “r” is squeezed between “e” and “s”, which gives an appearance of an ink blot, this is clearly not the case.

Figure 2 Lord William Howard’s household accounts book, 1633–34. Payment to Robert Hymers for dancing lessons. Howard of Naworth Archive, Carlisle Archive Centre, Carlisle, DHN/C/706/12, fo. 74v. By kind permission of Philip Howard.

We can therefore conclude that Mr. Robert Hymers, found in Lord William Howard’s household books under a variety of spellings, is most probably Robert Hindmers, the recusant dancer imprisoned by Bishop James in August 1615.Footnote 75 Bearing in mind the considerable lapse of time between the first and the last payment for dance instruction at Naworth – in 1634, Hindmers’ would have been in his sixtieth year – and the fact that in the early modern period musical and dancing professions were often transmitted within one family from one generation to the next, we need to recognize the possibility that the accounts from 1610s and 1630s could be referring to two different dancers bearing the same name. If all payments to dancing masters in Lord Howard’s account books refer to dance instruction conducted by a single individual, which is more likely, then Robert, who started off teaching young gentlemen to dance at least in 1613, reappears in 1630s as an established family dancing teacher. For over two decades, Hindmers would have been visiting Naworth rather regularly, providing dance education to at least two generations of Howards. Considering the social standing of his employers, we are safe to assume that Robert’s expertise was far from limited to rustic hopping and skipping. Although he must have been thoroughly familiar with popular country dances, whose derivatives were in vogue at Court, his dance repertoire could not have been limited to that tradition alone.Footnote 76 Since Robert Hindmers was a professional dance teacher employed by the aristocracy, he had to keep track of the latest tastes and fashions in order to satisfy his clients.Footnote 77

If Robert’s father, Richard Hindmers, was indeed a poor labourer as Bishop James suggests, then his wage in 1590 would have been around six pence, which would probably amount to around five pounds of yearly income, although such estimates of annual earnings are notoriously uncertain.Footnote 78 In contrast to his father, Robert earned two pounds for only one month of dancing lessons at Naworth Castle. Although such high earnings were probably irregular, it is hard to imagine Hindmers leading a life as financially precarious as his father. Robert’s income would have been substantially smaller than the earnings of the court-based dancing masters, whose annual income could amount to more than 150 pounds, but Hindmers’ monthly rate was nevertheless the same as those of other dance instructors to the aristocracy in the south, such as William Jarman’s, a dancing master to Algernon Percy, the future 10th Earl of Northumberland.Footnote 79

Given Hindmers’ social background, his connection with the Howards is even more significant: how could a labourer’s son became a dancing teacher in a noble household, and more importantly, where did he learn the art in the first place? At present, no satisfying answers can be given. Dancing masters were proficient in a number of skills tangential and auxiliary to their fundamental expertise in teaching fashionable dance. Apart from possessing substantial musical knowledge – they were versed instrumentalists, often using a kit (a portable miniature violin), which enabled them to provide music during the lessons – professional dancers were also choreographers of entertainments, and mediators of civility and bodily deportment.Footnote 80 Robert Hindmers would possess these gentlemanly qualities, which were deemed essential for appropriate conduct in polite circles, and duly impart them to his socially superior students.

Until now, the earliest evidence of a dancing master residing in Newcastle-upon-Tyne dates to the late seventeenth century.Footnote 81 Many occupational musicians, fiddlers, and pipers can be identified in early seventeenth-century Newcastle, and although their main profession was teaching and performing music, some of them might have occasionally offered dancing lessons as well in order to capitalize on the proliferation of courtly fashions at Newcastle and its growing market for a more sophisticated dance culture.Footnote 82 Moreover, dancing was not only central to the emerging town civility and sumptuous festivities at Court, but also to the rural sociability in the country, where, according to Nicholas Breton, ‘dancing on the greene, in the market house, or about the May-poole’ was essential on holydays.Footnote 83 Robert Hindmers and his wife Anne would have probably engaged socially and professionally both with the polite society and the rustic milieu of mirth, which earlier in their lives would have allowed them to practice their first dance steps and develop an appreciation for the art. The Hindmers were bridging and crossing social divides and boundaries and were not too unlike brothers George and Robert Cally, musicians and dancing masters of Chester, who, according to Christopher Marsh, acted as ‘cultural conduits’, traversing society and transporting ‘tunes, terms and choreographies from one place to another’.Footnote 84

Although we should not expect Robert Hindmer’s mastery of dance to be on a par with the virtuoso dancers active at Court, such as Barthélemy de Montagut, author of a plagiarized dance treatise and a dancing master of George Villiers, his skills were nevertheless considered exquisite enough to secure him employment in the noble household.Footnote 85 Sometime between c. 1600 and 1613, Robert must have refined both his manners and dancing abilities, which could hardly have been picked up on Sunday evenings in a local alehouse, and had become by the 1610s a fully developed dancing master, generously supported by Catholic patrons.

Dance and the Catholic community

For Robert Hindmers, dance, or more precisely, teaching dance was not merely a pretence, but his occupation. According to James, Robert ‘by his daunceing crept into manie houses’, where he and his young wife Anne, who accompanied him on his travels, ‘haue done much harme’.Footnote 86 It is very unlikely that dance itself would have been the cause of this harm. However, it is worth stressing that within particular circles and contexts dance in post-Reformation England could have been perceived as a sinful practice associated with traditionalist culture and the old faith.

In the course of the Reformation, dance, as well as stage plays, bearbaiting, May games, church ales, rushbearings, and other traditional pastimes and festivities, came under increased scrutiny and were by the end of the sixteenth century a focal point of sabbatarianists’ cultural criticism.Footnote 87 The more zealous sort of Protestants were not only attacking the habit of Sunday dancing, but also denounced dancing itself, which was normally considered adiaphoron, as intrinsically sinful and nearly unacceptable at any time or in any form. Although authors such as Christopher Fetherston and, half a century later, William Prynne tolerated dancing found in the Holy Scriptures, which is always single-sex, sombre, unaffected, and devotional, they deemed it fundamentally alien to the dancing practices of their own times.Footnote 88 To defend biblical dance, they historicized it and presented it as culturally obsolete. In contemporary society, they argued, spiritual joy finds its principal expression in ‘Psalmes, and Himnes, and spirituall Songes’ rather than in dance, which is now solely driven by lust.Footnote 89 The Neoplatonic notions of dance, which dominated the Court and were famously articulated by John Davies in Orchestra (1596 and 1622), could not be further from the moralists’ perspective, who described dancing as lewd, lascivious, heathen, and closely associated with practices of the old, superstitious faith.Footnote 90

Reformers broadly agreed to ‘prohibit dancing that either coincided with church services or took place in the sacred space of the church or churchyard’, but up to the publication of James I’s Book of Sports on 24 May 1618, the more fervent ministers could extend such orders to any part of the Lord’s Day.Footnote 91 Therefore, the acceptability of dancing in practice generally depended on whether it occurred in suitable places, at suitable times, and in a reverent and seemly manner. Moreover, those involved in parish dancing were rarely presented before visitation commissions and subsequently tried at a consistory court if the local community had not already been burdened by the ‘pre-existing tensions and disagreement about the acceptability of dancing in particular contexts, such as on Sundays, in the churchyard, or as part of traditional festivity’.Footnote 92

In the eyes of the Puritan ministers and preachers, dancing and other pastimes had been hindering the formation of a truly godly nation by representing means for Catholics to defy the ecclesiastical establishment and engage in unwanted conviviality, which reiterated their survivalist identity.Footnote 93 The association between traditional festivity and Catholicism was particularly strongly articulated from 1587 onwards by a number of Lancashire ministers. Their periodical fervent suppressions of Sunday recreations, and local resistance to their policies, stimulated the formation of the Book of Sports, initially issued in August 1617 exclusively for Lancashire as a Declaration Concerning Lawful Sports.Footnote 94 William Harrison, a preacher of Huyton near Liverpool, blamed the slow progress in bringing people to the obedience of the Gospels on ‘popish priests’ and ‘profane Pypers’, who every Sunday drew hundreds of people away from the church onto the village greens to participate in ‘lasciuious dancing’.Footnote 95 The greatest ‘maintainers of this impiety’, he claimed, were ‘our recusants and new communicants’, who by such means ‘keep the people from the Church, and so continue them in their popery and ignorance’.Footnote 96

The cultural activity of the recusant and musically talented Blundell family of Little Crosby in Lancashire testifies that the preachers’ outbursts were not simply rhetorical fantasies of the godly.Footnote 97 Rushbearings and May games in Cheshire, Lancashire, and Yorkshire would often have recusant overtones.Footnote 98 There is evidence of similarly contentious festivity and sociability amongst Catholics in Westmorland, Northumberland and Durham, including the setting up of a Christmas Lord, communal hunting, bowling, and horse-racing.Footnote 99 Intriguingly, the association of pastimes with Catholicism is also present in the Book of Sports itself, yet this time in order to curb and not advance the suppression of Sunday recreations. The king believed that Puritan disregard for traditional pastimes was in fact hindering ‘the conversion of many’, who might, prompted by popish priests, think ‘that no honest mirth or recreation is lawful or tolerable in Our Religion’.Footnote 100 Nevertheless, the Book of Sports denies the benefit of Sunday recreations to convicted recusants and church absentees. In other words, one had to conform to take part in parish sociability. The management of mirth was clearly significant not only for preserving royal authority and promoting royal policies, but also for achieving religious conformity.Footnote 101 With the Book of Sports, King James reacted not only against Puritans, but also Catholics, who had already taken advantage of controversies surrounding traditional culture by using it for proselytizing and asserting their religious identity.

Early-seventeenth-century traces of dancing practices in north-eastern England are scarce, and even more so among the Catholics. Yet the evidence of social occasions which might have included dancing are not difficult to identify. Trade companies and civic corporations of Durham and Newcastle regularly hired musicians for their annual feasts and holyday recreation, which undoubtedly included dancing.Footnote 102 The order of Newcastle Merchant Adventurers from 1603, which aimed to curb unseemly sociability of their apprentices, names dancing, along with dicing, carding, mumming, and taste in expensive clothes, as one of the vices the youths were forbidden to indulge in on the city streets.Footnote 103 There is also some evidence of professional instruction aside from the work of Robert Hindmers. In Durham City, Thomas Edlin was teaching dancing before he died in May 1620; most likely, he was an itinerant teacher, since he is described as ‘a strainger’.Footnote 104

Although Counter-Reformation Catholicism harboured similar attitudes towards superstitious devotional practices and profane recreations as Protestantism, it nevertheless, when necessary, harnessed festivity and popular rituals as instruments of confessionalization instead of bluntly suppressing them.Footnote 105 Even some Jesuit-friendly households, most strictly fashioned according to Tridentine values, did not completely oust holiday revelry from within their walls. Such was Dorothy Lawson’s semi-monastic institution near Newcastle, which was publicly marked as a Catholic house of worship with a sacred name of Jesus (the Jesuit emblem) on its wall facing the Tyne waterside. Behind its walls there was a chapel consecrated to the Mother of God, while each of the other rooms in the house was dedicated to a particular saint according to Robert Southwell’s recommendations.Footnote 106 It was a Catholic recusant space par excellence. In St. Anthony’s on Christmas Eve, after confessions, litanies would begin at eight in the evening, and would last, together with a sermon, until midnight, when three Masses were celebrated consecutively. Afterwards, the attendants broke their fast with a Christmas pie and then departed to their respective homes.Footnote 107 However, Dorothy Lawson did not feast her neighbours and tenants only spiritually, but also corporally, unbinding ‘in this time of mirth and joy for his birth who is the sole origin and spring of true comfort’ her ascetic stiffness to allow herself playing cards on Christmas day for ‘two hours after each meal’ and spending a shilling ‘among her friends to make them merry’.Footnote 108 Furthermore,

[s]hee had in a room near the chappell, a crib with musick to honour that joyfull mystery, and all Christmass musicians in her hall and dining chamber to recreate her friends and servants. Shee lov’d to see them dance, and said that if shee were present, greater care would be taken of modesty in their songs and dances.Footnote 109

The Jesuit William Palmes constructs the life of Dorothy Lawson in accordance with post-Tridentine ideals of piety and Christian living. Revelry, which the matriarch observes with a slight suspicion, does not at all assume a central role in the household holiday celebrations, but it is nevertheless vital, since, to use Southwell’s words, ‘tyred spirites for mirth must haue a time’.Footnote 110 Dorothy Lawson’s monastic restraint from worldly pleasures is thus balanced by acknowledgement that on feast days bodily recreations and outward expressions of joy through music, gaming, and dancing are as important as penance and religious meditation. At St. Anthony’s, whose first stone was laid by Richard Holtby, a Jesuit Superior, and where Jesuits were employed as resident chaplains, festive revelry was clearly indispensable at Christmas and in spatial proximity to richly adorned chapel and sacred solemnities.Footnote 111

Ecclesiastical records can give us further insight into the social life of the north-eastern parishes. In 1607, Toby Matthew, who had vacated the see of Durham in benefit of William James and assumed the archbishopric of York, produced a set of influential visitation articles for the whole province. The articles request the ministers and churchwardens to inquire whether in their parishes and chapelries there are any ‘rush bearings, bull-baytings, may-games, morice-dances, ailes, or any such like prophane pastimes or assemblies on the sabboth to the hinderance of prayers, sermons, or other godly exercises’.Footnote 112 Extant visitation books for the diocese of Durham only rarely mention illegal dancing. Instead, they refer to a number of controversial social occasions on which dancing was commonly practiced or encouraged.Footnote 113

In November 1615, William Harrison, his wife Isabella, and John Gowling were presented before archdeacon William Morton at Barnard Castle – the latter for piping and ‘those two dauncing vpon the saboth’.Footnote 114 No information is given of either exact time or place of their dancing. Other cases heard before archdeacons John Pilkington and Morton convey a picture of pervasive communal recreations and thriving festive culture. At Winston, a village near Darlington, John Stanton and Robert Hewetson were presented in 1603 for ‘maikinge a drinkinge on the Sabbaoth daie’ and ‘makinge a may game on the Sabbaoth daie’ respectively; undoubtedly they were both involved in organizing the same event.Footnote 115 We find more contested may-gaming two years later at Bishop Middleham, where Randal Watter and five others were suspected of bringing ‘a may pole into the towne vpon assention day last’.Footnote 116 May game celebrations often included morris dancing, but setting up and dancing around the maypole would have been even more common.Footnote 117

A strong resistance to John Pilkington’s sabbatarianist tendencies can even be detected at the heart of his archdeaconry, at St. Nicholas in Durham. On 7 July 1603, the churchwardens of the parish were presented for allowing ‘drinking banquetting & playing at cardes, and other vnlawfull gaimes’ in alehouses in time of divine service.Footnote 118 It was precisely due to such leniency on the part of churchwardens that more unlawful dancing had not been detected in the city.Footnote 119 Disorderly Sunday gatherings in alehouses and private homes which involved drinking and gaming are otherwise often reported throughout the county.Footnote 120 Occasionally, such conviviality is more distinctly paired with charges of non-communicantcy or even recusancy. In Benton, just outside Newcastle, Christopher Dawson entertained ‘a companie of fidlers playing at cards in his house on the first sondaie after the Epiphanie last [in 1620] all the tyme of dyvine service and administration of the holy Communion’.Footnote 121 The fiddlers, John Hobkirk of Newcastle and John and William Hatherwick, had abstained from fiddling during the service, which they failed to attend, but instead amused themselves with cards before probably assuming the revels again after divine service. Agnes Walker, a Berwick recusant, entertained a ‘Companie drinking in her house on sundaie vijo Junij 1620’ and kept her front door closed ‘against the Churchwarden that daie, and let the Companie goe forth at the back dore’.Footnote 122

Although dancing is never specifically mentioned in such cases, the alehouse keepers at least, such as Robert Burden and Anthony Learman from Bishopwearmouth (now part of Sunderland), who hosted ‘drinkers in ther houses in tyme of prayers’, had a vested interest in attracting and entertaining their guests by providing dance music.Footnote 123 They might have employed someone like John Wilson from South Shields, who was presented to the Cathedral authorities in February 1612 ‘that being the Piper & the wait, there pipeth euerie sabboth daie & hollidaie at Alehouse in the forenoone’.Footnote 124

Whether there were ulterior motives behind any such instance of disorderly drinking, gaming, and dancing in private homes, such as luring Catholic sympathizers away from church-going, is hard to ascertain. The post-Reformation attack on traditional culture had stimulated some Catholics to preserve and treasure those ceremonies and recreations which in the eyes of the radical Protestants defined them as a coherent and oppositional religious group, but we should be careful not to associate just any unruly festivity with Catholicism.Footnote 125 However, the Hindmers’ case informs us that the crowd of Durham Sabbath profaners must have also included recusants, some of whom, like Anne Hewes from Cheshire, might have been both ‘seduceing papist[s]’ and ‘daunceinge vpon ye Saboth daie’.Footnote 126

Creeping into houses

Although moral critique of dancing is undoubtedly implied in the private correspondence between two Calvinist clergymen, the language of Puritan sabbatarianism, linking Catholicism with disorderly, heathen, or even seditious festivity, is absent in Bishop James’ letter, not least because his main concern is fervent recusancy, and not festive traditionalism. Rather than claiming the harm was caused by dancing itself, James seems to be suggesting that dance, much like music in the case of John Jacob, had been cunningly used as an expedient to gain entry into private houses and disseminate without suspicion far more harmful matters than the latest dance moves. By employing the language of religious controversy, James strengthens his identification of the Hindmers as Catholic proselytizers. The aforementioned report on recusancy in the bishopric, issued by William James in 1608, uses familiar phrasing:

There is no doubt but amongst so many Papistes in so remote a Countrey sondrie Semynaries are crept in & keepe resdences, to the dalie withdrawing of the kinges people, who though they be not verie obvious, yet vpon searches might no doubt be apprehended.Footnote 127

In the bishop’s vocabulary, the verb “to creep in” does not denote just any stealthy, cautious, scheming, and unobserved intrusion or advancement. It is particularly associated with the practices of “popish” priests, who, in order to evade persecution, had to abandon their clerical dress and travel in disguise. The expression is in fact a commonplace in both anti-Catholic and anti-Protestant polemics and derives from Paul’s second epistle to Timothy: ‘For of this sort are they [hypocrites] which creep into houses, and lead captive silly women laden with sins, led away with divers lusts’.Footnote 128 Protestant works, such as John Baxter’s A Toil for Two-Legged Foxes (1600), Samuel Harsnett’s A Declaration of Egregious Popish Impostures (1603), and John Gee’s The Foot out of the Snare (1624), which attacked and exposed alleged devious missionary practices of Catholic priests, thrive on identifying Jesuits and seminarians with sly false prophets, invaders of households, and undercover womanizers.Footnote 129

In numerous Catholic households, the spousal division of labour in upholding Catholicism was necessary. In order to avoid recusancy fines, maintain Catholic identity, and satisfy the dictates of conscience, husbands would outwardly conform and ‘peepe into the Church once in a month’, while their wives would abstain from attending the parish church entirely.Footnote 130 Although married women were convicted and fined for recusancy, their forfeitures could never be extorted while their husbands were alive, since legally they did not possess any goods or lands.Footnote 131 Later Elizabethan and particularly Jacobean statutes tried to address the issue of non-conforming wives more vigorously by threatening their husbands, who were deemed bad patriarchs for not securing religious conformity in their households, with additional penalties and civil disadvantages.Footnote 132 The popular imagination responded to women’s substantial influence in Catholic households and their role in harbouring priests. Because sharing a roof with secular women became a norm for priests in seventeenth-century England, anti-Catholic and particularly anti-Jesuit tracts were keen to point out that popish seduction was not only religious, but also sexual: priests were frequently accused of adultery, recusant women of whoredom.Footnote 133 Anti-Catholicism was paired with misogyny.

In light of the subversive role of Catholic women, it does not come as a surprise that polemicists adopted 2 Tim 3,6 as a focal reference for describing the unsettling heterosocial relationships between popish priests and recusant women, while the phrase “creeping in” or “creeping into houses” became widely used with regard to secret intrusions of priests, sin, abuses, and superstitions either in private homes or worship more generally. John Baxter thus claims that Jesuits (or Foxes), ‘by dissembled zeale & palpable flaterie creepe into mens houses, winde themselues into mens consciences, lead away the simple captiue’.Footnote 134 In the fervently anti-Jesuit epic The Locvsts, or Apollyonists (1627), Phineas Fletcher laments that the ‘little Isle’ did not escape the scheming priests who

[…] with practicke slight

Crept into houses great: their sugred tongue

Made easy way into the lapsed brest

Of weaker sexe, where lust had built her nest,

There layd they Cuckoe eggs, and hatch’t their brood unblest.Footnote 135

After the Fatal Vespers in 1623, John Gee, a minister with previous Catholic inclinations, turned distinctly anti-Catholic. In the wake of the accident, Gee was prompted by Archbishop Abbot to write a penitential tract exposing proselytizing strategies of popish priests. In the introduction of The Foot out of the Snare he wittily asserts that ‘our Countrey, which ought to bee euen and vniforme, is now made like a piece of Arras, full of strange formes and colours’.Footnote 136 The blame for religious divisions lies with lukewarm ministers and, more importantly, the emissaries of Rome, who

make them, whom they can get to work vpon by their perswasions, to become retrograde […] and become Apostates in matters of orthodox Christianity. Easily can they steale away the hearts of the weaker sort: and secretly do they creep into houses, leading captiue simple women loaden with sinnes, and led away with diuerse lusts. Footnote 137

Gee’s patron and the addressee of William James’ letter, George Abbot, had also engaged in anti-Catholic discourse in the Reasons which Doctor Hill hath Brought for the Upholding of Papistry (1604), as well as in a voluminous collection of thirty sermons, An Exposition upon the Prophet Jonah (1600). In the closure of the twenty-ninth sermon, Abbot explains that although there is no apology for sin, the fact that the weakness of sinners is often transformed into strength by God’s grace can also be used as a just defence against

Seminarie priests of Rome, who take occasion by reason of some slippes in our Cleargie, & defects in our ministerie […] to vnder-mine any good opinion of our religion in the simple: But this is practised most of all to the ignorant, and to silly women, into whose houses they creepe, and leade them captiue being laden with sinnes, and led with diuerse lustes.Footnote 138

The semantic field of Catholic “creeping” can be further extended by discussing a pious observance which might have informed and reiterated the Protestant pejorative use of the verb in anti-Catholic tracts.

Early in 1548 the government of Lord Protector Somerset (c. 1500–52) forbade a number of old Church ceremonies, such as the blessing of candles at Candlemas, ashes upon Ash Wednesday, foliage on Palm Sunday, and creeping to the cross, a Good Friday custom of venerating the crucifix.Footnote 139 How elaborate the practice of the creeping to the cross would have been in pre-Reformation England can be observed in the Rites of Durham, a work of Catholic nostalgia from the end of the sixteenth century, describing ceremonies in and around Durham cathedral before the dissolution of the monasteries.Footnote 140 It is easy to see why the Reformers abhorred such extravagant expression of faith, and also how infiltrating priests might have been reintroducing the practice in Catholic households. The ceremony was certainly observed in Dorothy Lawson’s house, where both Easter and Christmas were celebrated lavishly. During Holy Week, Lawson performed in her chapel ‘all the ceremonies appropriated to that blessed time’, including creeping to the cross, ‘which kissing shee bath’d with tears’.Footnote 141

Returning to the bishop’s letter, we can now decisively conclude that James’s language consciously compares the Hindmers and their itineracy with that of undercover seminary priests. He is not only describing Robert Hindmers as a dancer and a recusant, but also as a “seducing papist”, who ‘by his daunceing crept into manie houses’ and with “divers lusts” led people away from religious conformity.Footnote 142 For James, the fact that Robert is accompanied by his recusant wife reinforces Protestant stereotypes about the unruly Catholic women and gynocentric Catholic mission. Dance itself, on the other hand, is only tangentially under attack, although James seems to be anticipating later Caroline anxieties about the proliferation of the new French dance and decorum, which were often associated with emasculation, lewdness, Catholicism, and Jesuit influence.Footnote 143 In the 1608 recusancy report, the consequences of creeping in of seminary priests is described as a ‘daily withdrawing of the king’s people’, namely the shifting of individuals into religious and political nonconformity.Footnote 144 Bishop James clearly perceived and measured the damage of the Hindmers’ venture in similar terms.

Conclusion

We lack evidence to determine how precisely the Hindmers utilized dance in their proselytizing efforts. Bishop James certainly believed that Robert’s ability to teach dance enabled him to enter households and access particular communities. However, it remains unclear whether dancing lessons were anything more than a convenient cover story for unrelated missionary activities.

Using worldly recreations to evangelize was not an unprecedented practice. Jesuits did not understand proselytizing as a primarily polemical exercise and indeed used a variety of approaches to successfully convert heretics, schismatics, or lukewarm Catholics.Footnote 145 John Gerard took advantage of Sir Everard Digby’s love for hunting and converted Sir Oliver Manners over a game of cards; he clearly approached the spirit from the flesh.Footnote 146 Dance, so prevalent in English early modern culture and already widely associated with Catholicism, both in the country as well as at Court, particularly due to the two Stuart Queens, could hardly have been an inappropriate method for accessing festive-traditionalist elements of society, who sympathized with the old faith.

Although the notion of ‘converted’ dance forms, which might have mirrored the ‘converted’ ballads discussed by Murphy, is compelling, we have no evidence to confirm their existence. However, dance would not have to be necessarily made “Catholic” in order to serve the mission. In the early modern period, dancing was perceived to fulfil an important social function of bringing young men and women together. In fact, the social mixer dances, a special group of dances designed to achieve more unexpected intermingling of the participants, provided ‘a structured form for flirtation, usually in a safe and supervised context’.Footnote 147 If dancing lessons were conducted by the Hindmers, they may have been utilized to facilitate such sociability among the local Catholic youth. Moreover, it is not hard to imagine how private dancing might have brought like-minded people together not only to socialize, but also to exchange news, pray, and worship.

Much like the Simpson players, a semi-professional recusant theatre company from Egton, which toured the North Yorkshire households in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, the Hindmers’ dance events probably participated in communal affirmations of Catholic identity.Footnote 148 However, such entertainment, which involved individuals both physically and mentally, could quickly yield more subversive and far-reaching consequences. A telling rumour spread in the wake of the Simpsons’ Christmas performance at Gowlthwaite Hall in 1609. Some of the ‘Popishe people’ present at the performance of the Saint Christopher play alleged to their neighbours ‘that if they had seene the said Play […] they would neuer care for the newe lawe or for goinge to the Church more’.Footnote 149 Participating in communal entertainment could have a significant impact on individual’s religious identity.

Robert Hindmers used his talents to defy poverty and advance the Catholic cause. He received maintenance from local priests, but also managed to acquire more wealthy and powerful patrons, such as Lord William Howard of Naworth. Although Bishop James is quite clear with regard to the nature of the harm which Robert and Anne caused, the evidence does not explicitly link dancing lessons with religious instruction. And yet, precisely because Robert Hindmers was a professional dancer, the importance of dance in his evangelizing activities should not be underestimated. Allowing a dancing master to assist the missionary priests without utilizing his unique skills would seem like a conspicuous waste of talent.