INTRODUCTION

Excavation of the Roman fort on Brough Hill at Bainbridge, in Wensleydale, North Yorkshire (SD 937 902), began in 1925 and continued intermittently in short summer seasons for a period of fifty years. Seventeen seasons were directed by Brian Rogerson Hartley who taught at Leeds University from 1956 to 1995 and continued the university's training excavations at the fort which had been started in 1950 by his predecessor at Leeds, William V. Wade. Hartley worked at Bainbridge in 1957–64, 1966–72, and in 1974 and 1977; he also excavated the forts at Adel (1957), Ilkley (1962), Bowes (1966–67 and 1970, with S.S. Frere), Slack (1968–69), and Lease Rigg (1976, 1978–80, with L.F. Fitts). This series of excavations was described by Frere as a ‘programme of research’ on the Pennine forts.Footnote 1 Hartley reviewed the results of this work in two influential articles,Footnote 2 and his last extended consideration of the problems of northern England under the Romans was his book, The Brigantes, which was written with L.F. Fitts and published in 1988.

Hartley published his first three seasons of work at Bainbridge.Footnote 3 The fourteen seasons after 1959Footnote 4 are the subject of the present study, which provides a full structural account of the remarkable sequence of three successive principia — Flavian, mid-Antonine and Severan — and a discussion of its implications for the history of the fort and for our understanding of the evolution of the principia as a building type from the later first to fourth centuries. Descriptions of the small finds are also included. All the coarse pottery has been spot-dated, although it is not published here; use has also been made of Hartley's notes on the dating of the samian ware recorded in the context books.Footnote 5 Other aspects of Hartley's excavations are incorporated in a brief summary of what is known about the other buildings of the fort, its defences and its walled annexe, which is based on the surviving records and finds. The Supplementary Material (see http://journals.cambridge.org/bri) contains detailed accounts of the excavations summarised here, together with finds reports and two unpublished studies undertaken independently of this project: the conclusions of a report on the animal bones by Caroline Middleton and a survey of the fort at a scale of 1:500 and a wider survey of its immediate landscape at 1:1000 carried out by RCHME in 1994 which are reproduced here as online figs 31 and 32.

In 1975 or shortly after, Hartley began to write a full report on the Bainbridge excavations, working directly from the site records. He drafted the introduction and a summary of the Flavian–Trajanic fort and had started to describe its principia in detail when he set aside the project. The first and last of these sections are included below, omitting material which is no longer relevant, and the other section is included in the Supplementary Material. He also prepared a fine series of plans of the principia which were published in interim reports and are reproduced here as figs 7–8, 12 and 17, with some additions. There is also a general plan of the fort ( fig. 2) which was not published by Hartley and has likewise been amended. Most of the other illustrations have been prepared for this report. There is more in the Bainbridge archive that merits publication at some stage, but this article and the Supplementary Material have concentrated on the structural sequence, which is the most important contribution that Hartley's work on the fort can make to the archaeology of Roman Britain and of Roman forts in general.

THE SETTING OF THE FORT AND ITS HISTORY OF RESEARCH By B.R. HartleyFootnote 6

Brough Hill at Bainbridge (the name Brough-by-Bainbridge seems to have been coined by R.G. Collingwood) lies at the watersmeet of the Ure and the Bain, immediately east of the latter. The hill is a drumlin, but larger than most in Wensleydale. As such it has relatively steep flanks and an upstream (western) end broader and higher than its downstream one, which offers the only easy approach to the site. Geologically then, the hill is a mixed glacial deposit, though boulder clay predominates at its surface. This normally has an orangey-brown weathered (in effect rusted) surface, but is greenish-grey a few centimetres down, where it has been protected from oxidation. The solid geology below these glacial features belongs to the Carboniferous system, the hill resting on limestone of the Yoredale series, as may be seen from the gorge cut by the Bain. At Bainbridge the upper flanks of the Dale are sandstones and fine-textured grits. The limestone seems not to have been used much by the Romans until the later fourth century, except in the form of boulders from the river and, presumably, in preparing lime for the mortar. From the earliest occupation the sandstones were widely used. As well as yielding good ashlars for facing walls, they also offered beds producing slabs 0.05–0.07 m thick useful for flooring, and thinner slabs which made good roofing slabs, normally pierced for nails. Accordingly, tile was rarely used in the fort, except presumably in hypocausts. No definite evidence has ever been found of the water supply to the fort. The water table is so far down as to eliminate the possibility of wells and it follows that a piped supply would have been essential. Of the two possible sources — the Bain above the level of the fort and the springs which exist on the south side of the Dale just above its level — the Bain must be eliminated, since the cutting of an aqueduct would have been exceedingly difficult. Evidently, an inverted siphon is in question, using the causeway of the south gate to enter the fort (the east gate has no trace of a pipe-line). Presumably, branches, or separate lines, would have served the vicus and the fort's bath-house, which lay in the annexe to the east of the fort.

Under natural conditions the clays of the Dale's floor would have supported dense vegetation and in the Roman period would presumably have been more heavily wooded than now. No pre-Roman or Roman native sites are known in the bottom of the Dale. In the vicinity of Bainbridge, most sites are at or above the level of the fort on the flanks of the Dale. There is a heavy concentration up the Bain valley and on the slopes of Addleborough.

Comparatively little is known of the Roman roads approaching the fort ( fig. 1). Clearly one must have existed up the Dale. It has been usual to assume an approach from Healam Bridge along the south side of the Dale through Aysgarth, but one must admit that there is no certain trace of it on the ground, and in view of the discovery of a fort north of the Ure at Wensley, near Bolton Castle,Footnote 7 it now seems more likely that the present course of the north road up the Dale through Redmire and Carperby represents the Roman road. A ford or bridge crossing the Ure to the north-east of the fort is therefore to be expected. The road south-west from Bainbridge heading by Ingleton, and presumably linking with Lancaster, has long been known and is perfectly visible from the site (though only because it was re-used in the eighteenth century for a turnpike).Footnote 8 One point worth noting is that it appears to be aligned on the centre of the visible fort. The road over the Stake Pass into Wharfedale was traced in the early 1930s.Footnote 9 Although its precise course down Wharfedale is in doubt, there can be little question that it linked Bainbridge to Ilkley. It seems probable that there was a road higher up the Dale than Bainbridge. A strong case may be made for postulating one on the north side of the Dale, continuing the line of the road from Healam Bridge suggested above. It is tempting to suggest that this road swerved north up the Mallerstang to link eventually with Brough-under-Stainmore. (The course of Lady Anne Clifford's Way through the Mallerstang looks suspiciously like Roman engineering.) Finally, it is often conjectured that a road leading north from Bainbridge crossed Askrigg Common to Swaledale, where it is likely to have headed for a putative fort at Reeth.Footnote 10 The terrace of the road approaching the south gate of the fort is perfectly clear on the ground and the cutting at the foot of the hill must be Roman and have led to a crossing of the Bain, where a bridge would have been necessary.Footnote 11

FIG. 1. Bainbridge and Wensleydale in their wider Roman setting. Camps, towers and fortlets omitted on the line of the road across Stainmore, from Brough to Bowes. Cave names as follows: Attermire Cave (A); Dowkerbottom Hole (D); Greater Kelco Cave (G); Jubilee Cave (J); Kinsey Cave (K); Sewell's Cave (S); Victoria and Albert Caves (V).

Antiquarian sources, and early editions of the Ordnance Survey, assign the name ‘Bracchium’ to the fort and they invariably talk about a ‘summer camp’ on the top of Addleborough. The name is a palpable nonsense owing to Camden's failure to understand RIB I, 722. Needless to say, the ‘camp’ does not exist.Footnote 12 Bainbridge escaped the attentions of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century antiquaries and it was not until 1926 that any archaeological excavation was done. At that time, Dr J.L. Kirk began work under the auspices of the Roman Antiquities Committee of the Yorkshire Archaeological Society. His work included a section through the west rampart north of the west gate. A copy of his drawing of the section exists at Bolton Castle, but it was never published. It was at this point that a curious episode intervened. The Committee invited R.G. Collingwood to act as ‘archaeological expert’ at the excavations. It is evident that Collingwood in effect took over from Kirk and it was his report which was eventually published. Attention was focused on the back of the principia and on the east gate, though sections were also cut through the rampart, and narrow trenches were dug in several parts of the interior. Subsequent work in 1928, 1929 and 1931 was done by Professor J.P. Droop of Liverpool. This added the enclosure wall of the vicus east of the fort and showed that the area inside the east gate had a complicated series of buildings which was not satisfactorily sorted out at the time. Droop, incidentally, wrote the standard text book on excavation current in the 1920s.Footnote 13 His work at Bainbridge scarcely lived up to his own standards. Note that both he and Collingwood sought to explain away the straightforward evidence for the late date of the east gate. We now know that the original gate was to the south, in the axial position. Many of the areas dug in 1925–31 were left open, with consequent damage to the surviving Roman walls. The finds from the pre-War excavations were kept at Cravenholme by the owners of the site (the Terrys). They were taken to Bolton Castle for safety during the 1939–45 war, but many (presumably including the inscription RIB I, 724) disappeared. Some of the pottery was salvaged, however, and this is now with the more recent finds. The University of Leeds acquired a lease of the fort for archaeological purposes in 1950 from Mr Leonard Scarr of Cravenholme Farm, and since then the site has frequently been used during the summer for training undergraduates, and others, in archaeological techniques. Most of the trainees came from the ranks of the Greek, Latin and History Departments until the creation of the Department of Archaeology in 1974.

THE DEFENCES AND INTERIOR BUILDINGS OF THE FORT (EXCLUDING THE PRINCIPIA)

THE EARLIEST OCCUPATION AND THE FLAVIAN–TRAJANIC FORTSFootnote 14

Casual use of the fort site in prehistory is suggested by the recovery of a few lithics. The fort platform, still visible as a prominent earthwork, preserves a Flavian–Trajanic defensive circuit which, though much rebuilt, remained until the end of the Roman period. However, there was an earlier period of Roman occupation represented by post-pits under the west rampart, principia and buildings in the praetentura of the Flavian–Trajanic fort; in addition, the post-trench of a building in the retentura cut earlier paving. The ramparts also incorporated Flavian pottery from earlier occupation of the site. The date of the samian ware from the whole site left no doubt in Hartley's mind that occupation began in c. a.d. 80, so the earliest remains must be associated with an Agricolan military presence. Hartley thought it possible that the earliest occupation represented a fortlet, but the extent of the remains strongly suggests a short-lived fort, its site at least partly overlapped by its Flavian–Trajanic successor. It might have replaced the fort at Wensley 15 km to the east, where Wensleydale opens out to a lower-lying landscape. The latter is known only from an aerial photograph and could date to the early a.d. 70s.

What appears to have been the second fort at Bainbridge had an area of about 1.1 ha (2.8 acres) measured across its ramparts ( fig. 2). None of its gates has been seen, but the position of the principia indicates that they were in much the same position as those of the mid-Antonine fort. The rampart was c. 5.3 m in width and was built of turf on a bottoming of flat stones. Later defensive ditches have removed any definite remains of the original ditches. The principia are described in detail below. Nothing is known of the Flavian–Trajanic praetorium, though it undoubtedly lay to the south of the principia, since the granaries occupied part of the area north of it. In 1951, under the north wall of the Severan principia and c. 4.5 m north of the Flavian–Trajanic principia, Wade found the south side of a stone building; it had two buttresses at its south-west corner and can be identified as a granary ( fig. 7).Footnote 15 Possible traces of a timber granary were found to the north. The stone granary was cut through a layer of carbonised grain, probably derived from the burning-down of an original timber granary. It seems then that there had been a pair of timber granaries north of the principia and that when the southern one had been destroyed by fire, it was rebuilt in stone. Between the granaries and the north intervallum street, there was another timber building fronting the via principalis. Barracks have been excavated in the southern part of praetentura ( fig. 3).Footnote 16 Their remains were fragmentary: they probably represented three barracks running north–south, which were not more than 26 m in length and just over 6 m wide, though other interpretations are possible. There were apparently two periods of construction.

FIG. 2. Overall plan of the fort and annexe, with excavated features of mid-Antonine and later date. For enlargements of the areas of the Antonine and Severan east gates, and of the granary and overlying buildings to the south-east, see fig. 4 and online fig. 36. The evidence for the building in the northern part of the praetentura is uncertain. Scale 1:1250.

Virtually nothing is known of buildings outside the fort, though presumably the contemporary vicus lay to the east. A length of wall beyond the site of the Severan east gate might have been part of the fort baths.

The samian ware incorporated in the rampart makes it clear that the fort was built after a.d. 85. As the new fort was a complete replacement of its Agricolan predecessor, a unit of a different type was probably now at Bainbridge. The small size of the fort might indicate that the unit was a cohors quingenaria peditata. This change probably resulted from a general redeployment of the army. There are two likely historical contexts: the withdrawal from most of Scotland in c. a.d. 87 and the consolidation of forces along the Tyne–Solway isthmus in the years following c. a.d. 105. On balance the earlier date seems preferable because of the slight remains of the earliest structures which do not suggest a lengthy occupation of the first fort. Abandonment of the new fort came early in Hadrian's reign at the latest. According to Hartley, ‘the pottery from the fort includes no black-burnished ware, and the samian is largely South Gaulish, though pieces from Les Martres-de-Veyre are not uncommon. Lezoux ware has never been recorded. In view of this, the latest possible date for withdrawal would be a.d. 125 and a connexion with the building of Hadrian's Wall is evident. This puts Bainbridge in the same category as, for instance, Ebchester, Ilkley or Brough-on-Noe.’

THE MID-ANTONINE FORT AND ITS LATER HISTORY

Hartley's narrative ended with his description of the Flavian–Trajanic principia. The later periods of activity are described by him in brief interim statements, but the detailed sequence has been worked out by an analysis of the site records. For the most part, Hartley's interpretations of the structural sequences hold up well. The first two periods of construction were of mid-Antonine and Severan date, though a new interpretation of the history of the fort defences and the annexe walls is offered here. Hartley proposed two further periods of construction — Constantinian (shortly after a.d. 296–97) and Theodosian (shortly after a.d. 367) — which are seen most clearly in the principia. In broad terms, these are accepted here. All four periods, of course, correspond to the Wall-Periods IB, II, III and IV. They represent a historical framework which, although not entirely superseded (for example, three Severan inscriptions make it certain that Bainbridge was partly rebuilt at the beginning of Wall-Period II), needs to be viewed alongside longer-term trends, both in Britain and in other European frontier areas.Footnote 17 There is not enough dating evidence at Bainbridge to ascribe alterations in the principia and other buildings specifically to the Constantinian or Theodosian periods, but there are sufficient grounds to place them in the later third and later fourth centuries.

The identity of the unit or units in occupation during the Flavian–Trajanic period is unknown. Cohors VI Nerviorum was at the fort by a.d. 205 and in the Notitia Dignitatum it is placed at Virosidum, which is almost certainly Bainbridge. The unit might also have been present in the Antonine period, but, as will be seen, there was a period of reduced occupation before a.d. 205; following this hiatus, the Nervians could have replaced another unit, perhaps cohors II Asturum, its presence suggested by a lead sealing.Footnote 18

THE FORT DEFENCESFootnote 19

The rampart of the Flavian–Trajanic fort was heightened and widened at the rear with turf and clay. Hartley regarded the fort wall as a later insertion, but this is not shown with any certainty on the section drawings of the defences. Part of the original stone east gate was seen in 1960; it appears to have had a single portal with an overall width of c. 4 m and no flanking towers ( fig. 4). The east gate was rebuilt further to the north when the Severan principia was rebuilt, so the original building of the defences in stone would have had to have taken place by the end of the second century, if not when the fort was re-occupied in the mid-Antonine period. When the east gate was relocated, the east fort wall was also rebuilt on a line c. 0.8 m behind that of the original wall. Single ditches are still visible on the north and south sides of the fort, though excavations by Droop in 1928 traced a second ditch on the north side; traces of five ditches can be seen extending for a distance of 38 m beyond the west rampart. The arrangements on the east side were complicated by the presence of the annexe and are described below. Gaps still visible in the rampart mound mark the sites of the south, west and north gates, which have never been excavated.

The Severan east gate remained in use until the end of the Roman period. This small area produced a disproportionately large number (46 or 24.7 per cent) of the Roman coins (186) recorded from the whole site. They consist largely of issues dating from the later third century to the Valentinianic period. As at the Minor West Gate at Wallsend, the high level of coin-loss in this area can probably be explained by its use for transactions between the fort garrison and itinerant pedlars and traders when there was no longer a military vicus outside the fort.Footnote 20

THE INTERNAL BUILDINGS (EXCLUDING THE PRINCIPIA)

The main streets of the mid-Antonine fort were in much the same position as those of its predecessor. The southern part of the praetentura was once again occupied by barracks ( fig. 3). There were three, running north–south, which were divided from each other by narrow eaves-drips. If the remains have been correctly understood, the central building could only have been entered from its narrow ends and had a passage connecting its contubernia, an arrangement which is without parallel in any Roman barrack. The western barrack was demolished before the Severan period; the middle barrack was either split along its length by a spine wall or reduced in width. Pottery dating to the second half of the second century was stratified in deposits associated with these barracks. In the Severan period, the line of the via praetoria was shifted northwards and presumably cut across the ends of barracks in the northern part of the praetentura. New barracks in the southern praetentura were probably part of a general rebuilding that followed the realignment of the street. Their remains were fragmentary but perhaps represented free-standing contubernia (so-called chalet barracks) forming two barracks built back-to-back and aligned north–south. Two further periods of rebuilding followed, but again the remains were fragmentary. In the northern part of the retentura, the excavations of 1969–72 and 1977 were limited in scope. There was a latrine building in the north-west angle of the rampart with a drain which seems to have run under the fort wall. Most of the excavated area was occupied by two successive stone buildings, which were probably barracks running north–south. To their north was an open area which was paved with flagstones and rubble after c. a.d. 360.

FIG. 3. The barracks in the praetentura, excavated in 1957 (after Hartley 1960, fig. 5); for their location, see fig. 2. Scale 1:1000.

FIG. 4. The Antonine and Severan fort walls and east gates; for the position of the trenches, see fig. 2. In 60 BII, the possible timber raft is shown with hatching of vertical lines. Scale 1:250.

In the central range to the south of the principia, trenches dug in 1926 traced paving, a gutter and walls which probably formed part of the praetorium. North of the principia, in the angle between the via principalis and the north intervallum street, there was a granary with an overall width of c. 6.7 m; a wall running up to its south-east corner probably enclosed a yard, the southern side of which would have been formed by a second granary. In northern England, the same arrangement can be seen at Ambleside;Footnote 21 these yards might have provided secure storage for supplies such as timber, barrels and amphorae which did not need sheltering from the weather. In the Severan reorganisation of the fort, a double granary measuring 19.5 by 17.5 m was substituted for the mid-Antonine buildings. After c. a.d. 360 the southern part of the granary was demolished and its site paved with large slabs. The northern part apparently continued in use until the end of the Roman period and certainly until after c. a.d. 370.

THE ANNEXE AND SURROUNDINGS OF THE FORT

In 1928 Droop discovered the later northern wall of the annexe and in the following year traced it eastwards until he encountered its turn to the south. He connected the wall with the ‘bracchium’ or annexe wall mentioned in the Severan inscription RIB I, 722. In 1931 he traced the rest of the circuit which enclosed an area, measured across the walls, of c. 0.75 ha ( fig. 5). Two gates or entries were found: on the eastern side there was just a gap in the wall, but on the northern side there was a more complicated arrangement which might have incorporated a flanking tower, though this is very far from certain. Equally uncertain is the existence of a gate or entry on the south side which might have been indicated by a possible interruption of the wall noted by Droop.Footnote 22 In 1958–59 Hartley cut a trench across the annexe wall; behind it he found an earlier wall backed by a rampart and with a ditch in front of it, the northern edge of which was cut by the later wall. A rampart, not seen by Droop, was also found behind the later wall.Footnote 23

FIG. 5. Aerial photograph looking north-west, showing the annexe (centre) and fort (beyond), with Cravenholme and the River Bain at the top. At first sight, the arrangement of the ditches on the west side of the fort might seem partly to preserve one side of an earlier fort, but this is illusory (see online figs 31–32). CIF 45, January 1979. (Reproduced with the permission of the Cambridge University Collection of Aerial Photographs)

Within the area of the annexe, Droop and Hartley uncovered parts of a number of buildings, and the RCHME survey recorded surface traces of others. In the north-east corner was a hypocausted building, probably the fort baths of mid-Antonine or later date and certainly not part of the possible baths of the Flavian–Trajanic fort immediately outside its east gate. South of the road leading to the Severan east gate, the north-west corner of a stone-built granary was seen; its long axis was aligned north–south and it was at least 14.5 m in length.Footnote 24 The granary was sealed by one or more buildings; from under what seemed to have been a primary floor of this later period of construction there was pottery dating to c. a.d. 250 or later. Droop uncovered the complete outline of a strip-house immediately south of the eastern entry into the annexe.

In 1960 Hartley regarded the earlier annexe wall as the Severan bracchium; its replacement on the north side he dated to the mid-third century.Footnote 25 Both Droop and Hartley noted the scarcity of fourth-century pottery in the annexe.Footnote 26

THE FUNCTION OF THE FORT AT BAINBRIDGE

Until the 1970s the function of the forts that remained in northern England after the Flavian–Trajanic period had seemed almost self-evident. The Roman occupation was disrupted, it was thought, by periodic barbarian incursions from the north, with their consequent trains of destruction which were apparent in the archaeology of the forts; besides which, there were always threats from the hill-folk. Forts were needed to control large areas of northern England and to defend those areas against internal and external enemies. This grim picture faded when doubts began to gather about whether there were destruction deposits in forts and whether this defensive system was needed. The new view — that the forts were primarily to hold reserve forces — was first expressed in connection with County Durham: ‘… the return of units in the a.d. 160s to Binchester and Ebchester need mean no more than that these sites were highly convenient for stationing units which could not be squeezed onto the Wall line but were part of the expeditionary force for activities north of the Wall …’.Footnote 27 This view was soon enlarged to encompass all the forts in northern England, but was explicitly rejected by Hartley who considered it still likely that there had been a Brigantian rebellion in the 150s and destruction of forts in a.d. 196–97.Footnote 28 In 2009 Hodgson and the present writer re-stated what were essentially the older beliefs about the significance of the Pennine forts, but justified them by a different line of reasoning.Footnote 29 Accepting doubts about the existence of destruction deposits and the Brigantian rebellion, the study concentrated on the settings and histories of the forts, which hardly seemed to accord with their use as bases for reserves. It was also questioned whether it was feasible to keep such large reserves in Britain during the later second century and beyond, given the grave military emergencies that confronted the Roman state elsewhere.

These matters are central to considering why there was a fort at Bainbridge. Its origin in the Agricolan period is unremarkable; it was one of a large number of forts which were established to control the recently conquered territories of the Brigantes. The re-occupation of the site in c. a.d. 160 took place in very different circumstances: northern England had been part of the Roman province for almost a century, and under Hadrian and Antoninus Pius the numbers of forts in the region had been progressively reduced. One particular aspect of the fort at Bainbridge which might shed light on its purpose is its small size (1.1 ha). Fort-sizes vary considerably at different periods, and also, to some extent, from province to province, but in second-century Britain they usually fall within the range of 1.5 ha to 2.5 ha, apart from smaller examples on the Antonine Wall where some units were apparently split between adjacent forts. Bainbridge is one of five markedly small forts in the Pennines and Lake District which had areas of between 0.92 ha and 1.2 ha: these other forts are at Whitley Castle (1.2 ha), Ambleside (1.18 ha), Low Borrow Bridge (1.16 ha) and Brough-on-Noe (0.92 ha). A sixth fort within this range of sizes, at Brough-under-Stainmore (1.16 ha), is possibly later Roman, replacing a larger fort.Footnote 30 All these forts were established in the late first or early second century and held until the end of the Roman period, though, except for Ambleside, with a period of abandonment c. a.d. 125–60. From the third century, or perhaps some decades earlier, cohors II Nerviorum was at Whitley Castle; cohors I Aquitanorum was at Brough-on-Noe from a.d. 158 until no later than the beginning of the third century. Bainbridge, as already noted, was occupied by a.d. 205 by cohors VI Nerviorum, possibly preceded from the mid-Antonine period by cohors II Asturum. The identities of the units at Ambleside and Low Borrow Bridge are unknown, though, as in the case of the other small forts, they will probably have been quingenary. Inscriptions and other written records of the units named above do not specify whether they were equitate or peditate, but the size of the forts they occupied is usually taken to indicate that they were peditate, requiring six barracks rather than the ten (four of them stable-barracks) needed for an equitate cohort.

However, a simple equation of the sizes of forts and units can be misleading,Footnote 31 especially from the earlier third century onwards when units began to be reduced in size,Footnote 32 and unfortunately, none of the plans of the barrack accommodation in the six small forts can be reconstructed. Another possible explanation for the small size of these forts is that they contained only parts of units. The smaller forts on the Antonine Wall have already been mentioned. Another fort comparable in size to our group is at Crawford (1.06 ha); originating in the Flavian period, it was re-occupied in the early Antonine period. As well as the principia and a granary, its interior contains barracks with a length of 19.8 m which were judged to be too short to contain complete centuries.Footnote 33 There was not enough accommodation for a complete quingenary unit, its remainder perhaps being posted at the fortlets and at least one tower which are known on roads to the south and north. A second possible example is Hardknott with an area of 1.3 ha, where the main occupation was confined to the Hadrianic period. It was held by cohors IIII Delmatarum, which, to judge by the size of its parade ground, was probably equitate. Part of the unit was probably stationed in a fortlet on the coast at Ravenglass, superseded by a fort with an estimated area of 1.46 ha when Hardknott was given up. However, these forts were comparatively short-lived, and it is doubtful whether a unit would have been permanently split between a fort and satellite fortlets. It seems best to accept that the units at our group of small forts in the second and third centuries were all probably quingenary peditate units, while admitting that there are other possibilities.

More can be learnt about the function of these forts by looking at their settings. Whitley Castle, Ambleside, Bainbridge and Brough-on-Noe can be described as remote forts, in the sense that they are on minor routes and are not links in a chain of forts, such as those on Dere Street or on the road which crosses Stainmore and runs up the Eden valley to Carlisle. These small forts are situated in valleys running through barren uplands; food from local agriculture would probably have had to have been supplemented from more distant sources. Brough-on-Noe was in an area ‘… on present evidence … very much less densely settled …’ than the river valleys in the White Peak to the south.Footnote 34 Field-systems and settlements have been mapped to the south of Bainbridge, but are far fewer in number than those known in and around Wharfedale and Malham.Footnote 35 Low Borrow Bridge, on a major route connecting Chester and Manchester with Carlisle and the western sector of Hadrian's Wall, is an exception to the remote positions of these smaller forts, but it is situated in the narrow, upper part of the Lune valley where it passes through the massive Howgills; local agriculture near by, particularly cereal production, must have been as limited as in the vicinities of the other small forts.

A possible connection between Whitley Castle, Bainbridge, Ilkley and Brough-on-Noe is their proximity to lead-mining districts. The association is strongest at Whitley Castle: from Brough-under-Stainmore there are lead sealings of cohors II Nerviorum inscribed ‘metal(la)’ on the obverse which probably date to the period when the unit was at Whitley Castle (RIB II.1, 2411.123–7), where possible by-products of lead smelting were used as aggregate in a mortar floor.Footnote 36 At Brough-on-Noe, galena was found in the principia.Footnote 37 The fort at Ilkley, which, with an area of 1.3 ha, is not much larger than the other forts considered here, is situated 16 km south of lead fields at Greenhow ( fig. 1), near which have been found lead pigs cast with inscriptions of Domitian and Trajan (RIB II.1, 2404.61–3). Bainbridge is also near lead fields, and the monks of Fors Abbey were granted the right to exploit them. Those rights were also to deposits of iron ore, which is a reminder that the Pennines were rich in other mineral deposits that might have been processed during the Roman period. In Britain, as elsewhere, the exploitation of valuable mineral resources did not in itself require the presence of the army. Military occupation at Charterhouse on Mendip in Somerset seems to have ended early in the Flavian period, even though lead-mining continued well into the second century and almost certainly much later.Footnote 38 Likewise, there are no clear indications of a military presence in the tin-mining areas of Cornwall after the early Flavian period. Any connection which Bainbridge, Whitley Castle, Ilkley and Brough-on-Noe had with lead-mining and other mineral extraction was likely to have arisen from a need to provide protection for the mines and the transport of their products in areas which were much less secure than south-west England.

The remoteness of these small forts in northern England might have been reflected in the size of their military vici. The annexe at Bainbridge contained vicus buildings, but it is uncertain whether there was also civilian settlement outside the defences. At Ambleside the vicus was extensive but seems to have been abandoned by the late Antonine period. Otherwise, very little is known about occupation outside the small forts. Their supply systems must have been more costly than those of forts on major routes, and, as suggested above, the upland settings of the small forts might have meant that they had to rely more on foodstuffs brought considerable distances than was usual for forts sited in less difficult terrain. At Bainbridge, recognition of the need for reserve stocks of grain much larger than at more accessible forts might explain the building of a granary in the annexe. The costs of servicing garrisons in these remote posts might explain their small size. On the other hand, the fact that these difficulties were accepted speaks of an imperative need to supervise and control a disaffected and troublesome population.

THE PRINCIPIA: FLAVIAN–TRAJANIC TO SEVERAN

A NOTE ON TERMINOLOGY AND THE RECORDING SYSTEM

The word ‘principia’ is a neuter plural noun, and R. Fellmann has recently deprecated its use as a single noun, which occasionally leads to the solecism of a plural ‘principiae’.Footnote 39 Not only this, but it also obscures the meaning of the word which refers to a number of different functional elements, only finally assembled in one building in the first half of the first century a.d. One of these elements was the shrine of the standards, or aedes principiorum, a term which occurs in RIB III, 3027 from Reculver and which is used here in preference to sacellum. The same inscription mentions a basilica, presumably the cross-hall. The English term is too well-established to abandon.

Hartley recorded his excavations in context books, usually one for each year, and by plans drawn to imperial scale. Usually, each area was given a letter preceded by the year of excavation, and each trench within that area was given a Roman number; all features and deposits were numbered continuously. Therefore, 64 GIII, 9 would be context 9 in Trench III, Area G, dug in 1964.Footnote 40 The trenches in the principia were generally of irregular size, their shape and position dictated by the need to answer specific questions ( fig. 6).

FIG. 6. Trench numbers on the principia site and position of section ( fig. 9). The north-easternmost trench was not numbered. Scale 1:250.

THE FLAVIAN–TRAJANIC PRINCIPIA (FIG. 7) By B.R. HartleyFootnote 41

There were several post-pits and other features in the subsoil which bore no relationship to the plan of the Flavian–Trajanic principia, and were cut by its post-trenches and post-pits, or were sealed by the earliest via principalis.Footnote 42 Since subsequent work has revealed similar post-pits under the west rampart of the first fort on the visible circuit, it now seems increasingly likely that its Agricolan predecessor was nearer the west end of the hill. Of the sixteen features recorded as likely to belong to the Agricolan phase, twelve were certainly post-pits, one may have been a post-pit, and the residue consists of one post-trench and two gullies. All the post-pits had clean fillings, save for the occasional flecks of charcoal, and, with only one apparent exception, produced no occupation material. Three coarse pottery sherds of Flavian or Trajanic date were recorded from the possible exception. But, since it was only realised later that the post-pit was cut by the Flavian–Trajanic veranda trench, the pottery may have been in the filling of the latter. The early post-pits fall into two groups. Four were large pits holding massive posts some 0.22–0.26 m square, packed with clay and stone. The other series of post-pits give alignments of three and four smaller posts respectively, all with posts 0.10–0.12 m in major dimensions, but not carefully squared, it seems.Footnote 43 For what it is worth, the two series are approximately at right angles to each other, but their alignments are different from the posts recorded under the Flavian–Trajanic barracks in the praetentura.Footnote 44

FIG. 7. The Flavian–Trajanic principia with earlier post-holes to north and outline of granary wall recorded by Wade in 1951. Scale 1:250.

The main difficulty in tracing the plan of the Flavian–Trajanic principia Footnote 45 which succeeded these features was that many of its post-trenches had been partly or totally destroyed in later reconstructions in the Antonine and Severan periods, particularly the latter. Both the south wall and the west one had entirely gone. However, the position of the former could be deduced by symmetry and the latter could be placed within a few inches. Its surviving returns to the east, considered together with the negative evidence of its absence west of the rear wall of the Severan building, where the subsoil was undisturbed, show that it was dug away when the Severan foundations were put in. Accordingly, the general plan may be restored with confidence, but the precise dimensions at a slightly lower order of confidence. The building emerges as a standard principia with forecourt and surrounding veranda, giving on to a covered transverse hall with four offices ranged about the aedes, which had a pit lined with concrete for the pay-chest. The walls were parallel to, or at right angles to, each other within a few degrees.Footnote 46 They had squared timbers, normally of 0.10–0.12 m scantling, but as will be seen from the plan ( fig. 7), the front wall of the hall had larger posts (about 0.25 m square) set in individual post-pits. There was no suggestion of a towering roof to the aedes, nor can there have been a central door in the front wall of the hall (but cf. below, ‘The Bainbridge principia: discussion’).

No trace of metalling was found in the forecourt, and normally an occupation deposit of brown earth capped with burnt material, including fired daub, rested directly on the subsoil. It is, however, possible that the entrance had been at least partly paved with flat slabs, since some were found on the subsoil close to the north veranda; gravel was also found at the entrance. Elsewhere in the court, it seems likely that timber duckboarding was laid, since in one area in the south-west corner of the court slight traces of dark striations in the subsoil suggested joists similar to those found in the timber barracks in the praetentura. Complete boarding would be impracticable in an open court, since it would become very slippery in wet weather, but duckboarding would be perfectly sensible in this context, and its use probably explains the absence of eaves-drip gullies around the veranda. Pit C had a gully draining into its south-west corner, as if it were acting as a soak-away. The gully had been lined with stone slabs, of which one survived. Pit D was of generally similar nature, but was apparently connected with a gully (E) too far to the west to take the eaves-drip from the eastern veranda. It may be suggested that this too served to drain the forecourt below the suggested duckboarding. The alternative that the gully (E) could have housed a wooden water-pipe, with Pit D as a small cistern, seems unacceptable, for there is no provision for dealing with the overflow, since the short stretch of gully on its north side sloped into, rather than away from, it.

No definite evidence of reconstruction within the Flavian–Trajanic period was noted. The building had been systematically demolished, with burning of the wattles and burial of the debris in pits, four of which were detected. Nails removed with claws were evident everywhere in the debris.

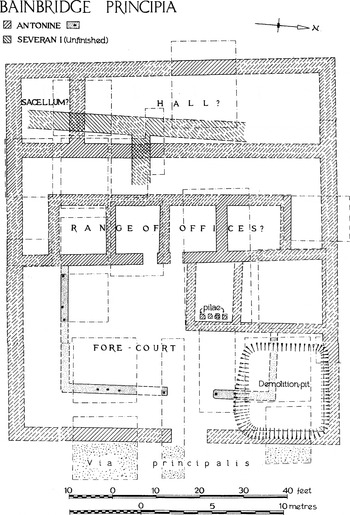

THE MID-ANTONINE PRINCIPIA: A UNIQUE PLAN OR A CONVENTIONAL PRINCIPIA PARTLY CONVERTED INTO ACCOMMODATION? (FIG. 8)Footnote 47

The mid-Antonine principia occupied the site of its Flavian–Trajanic predecessor, with its east–west axis 2.3 m farther to the north; its frontage was in roughly the same position as before, but it was a larger building and extended farther to the west as well as to the north, overlapping the Flavian–Trajanic stone granary. The new building was briefly described by Hartley as follows: ‘[it] was of unconventional plan, with a range of four small rooms taking up most of the space appropriate to the cross-hall, while the rear range appeared to contain one small room at the south end but otherwise to be undivided. The south half of the forecourt had a timber portico, but the north half was partly occupied by a stone structure, apparently involving a room with a hypocaust.’Footnote 48 The annotations on the accompanying plan ( fig. 8) label the four small rooms as ‘range of offices?’, the small room at the south end of the rear range as ‘sacellum?’ and the undivided remainder of the range as ‘hall?’. The only butt-joints shown on the plan are where the walls of the hypocausted room end against the east wall of the ‘range of offices’. Hartley clearly considered that all the elements of this curious plan were of one build, except presumably for the hypocausted room and its neighbour to the north. Yet, if this room and the ‘range of offices’ are extracted from the original plan, it leaves a conventional arrangement of forecourt, cross-hall and rear range, although the last apparently lacks the customary division into five rooms. It is therefore necessary to explore the possibility that the Antonine principia took the form of a conventional building which was later converted to serve other purposes by the addition of the ‘range of offices’.

FIG. 8. The mid-Antonine principia. Scale 1:250.

Hartley's plan implies the ‘range of offices’ were of one build with the longer wall which formed their eastern sides. If this longer wall formed the front of a cross-hall and the offices had been inserted subsequently, their walls would have abutted the longer wall. In fact, nothing more than the foundations of any of these walls survived, and it is impossible to be certain from the surviving plans and photographs (e.g. figs 18 and 20) whether or not they were all of one build. Re-examination of the records of the ‘Sacellum?’ and ‘Hall?’ to its north yielded more useful results. If these rooms had in fact been built as the rear range of a conventional principia, there should have been four cross-walls dividing up the area into the usual five rooms. The ‘Sacellum?’ would have formed the southernmost of these rooms. Just over 3 m beyond the north wall of this room, Hartley's plan ( fig. 8) shows a wide east–west foundation which was part of the initial work on the Severan principia, which was abandoned following alterations to its plan. This is shown clearly in a section ( fig. 9, H). Above the foundation is the south wall of the aedes of the completed Severan principia ( fig. 9, F with foundation-trench G). Below the foundation is a third wall ( fig. 9, I) which is pre-Severan and can only have belonged to the mid-Antonine principia where it presumably formed the north wall of a room next to, and of the same size as, the southern room in this range. Unfortunately, the next cross-wall to the north required in a conventional rear range would have been removed in the excavated area by the Severan strongroom, and the line of the fourth cross-wall would have lain entirely within an unexcavated area.

FIG. 9. Section across Room 2 and parts of the aedes (to left) and Room 1 (to right). Redrawn from TWM 30 with GI section reversed to face west. A: plaster adhering to walls or preserved on side of robber trench; B: possible hypocaust wall; C: general debris layer; D: ‘interference’ (possibly a robbed hypocaust wall); E: filling behind strongroom wall?; F: south wall of Severan aedes; G: cuts for insertion of F; H: foundation trench for first (abandoned) attempt at building Severan principia; I: mid-Antonine foundation trench, probably for south wall of aedes; J: mid-Antonine wall and foundation; K: robber trench for Severan wall built on stump of Antonine wall J; L: brown clay dump sealing foundations of J but cut by H; M: pit? For position of section, see fig. 6. Scale 1:75.

It is, therefore, likely that originally there was a conventional rear range of five rooms, which strengthens the case for there having been a standard cross-hall to the south, the range of offices being a later insertion. Just as important is the absence of any parallels for Hartley's building plan and the difficulties in analysing its function. If it is seen to represent two periods of construction corresponding to the successive functions which the building served, most aspects of its plans in both periods make sense, as is shown later in this structural analysis.

However, before returning to what will from now on be described as the cross-hall and rear range, the forecourt area needs to be discussed. The south side of the entry from the exterior of the building is shown as certain on fig. 8, but its position corresponds exactly with the south side of the entry into the Severan forecourt. There is no record of two walls in this position, though Hartley might have assumed that the Antonine foundations were re-used for the Severan wall. The south side of the opening, as shown on the plan, is nearly in line with the north end of a post-trench, separated by a gap 3 m in width from a short length of another post-trench on the same line, most of it destroyed by a so-called demolition pit. On the south side of the forecourt was another post-trench and there were traces of one on the north side, cut by the west side of the pit. Hartley regarded the post-trenches as parts of a veranda surrounding the forecourt on its south, east and north sides. There were timber verandas in the forecourt of the stone principia at Old KilpatrickFootnote 49 on the Antonine Wall, where the front wall of the cross-hall was also of timber while the rest of the building was of stone. However, at Bainbridge three closely-spaced post-impressions in the first of the trenches mentioned above held the uprights of a solid wall rather than the widely-spaced roof supports of the usual open veranda. These post-trenches might have been part of the later adaptation of the building. They do not have to be regarded as part of the primary construction: the rebuilt north veranda of the Severan principia shows that the bases of such supports could be placed on the ground without any foundations, and this might have been the original arrangement in the Antonine principia.

Another feature on the site of the principia forecourt is the so-called demolition pit.Footnote 50 It was roughly 6.5 m square and 1.9 m deep with sides sloping at angles of about 60 degrees; it contained two layers of burnt roof slates, charcoal and gravel, but most of its filling was of clay and ‘black earth’ mixed with stones. The top of the pit cut the inner edges of the north and east forecourt wall-foundations, but the pit might originally have had vertical sides which subsequently eroded, undermining the foundations. Whether this feature was a demolition pit is doubtful: it was not filled entirely with demolition material, and there is no obvious reason why a pit should have been dug to dispose of material which could have been included in street metalling, wall foundations and cores, and levelling layers for floors. Also, the uncompacted filling of the pit caused the collapse of the Severan forecourt wall which had been built above it. The pit would hardly have been dug in this position if it was to have been immediately succeeded by the rebuilding of the principia. It was probably associated with modifications to the principia, perhaps serving as a crude form of water-tank.

At first sight, the plan resulting from what is regarded here as the adaptation of the cross-hall is puzzling. Why were the four rooms inserted in the cross-hall rather than adapted from the five rooms of the rear range and why were there passages around three sides of the new rooms? The passages provide the answer. Many stone principia are reduced to their foundations, but where walls and door openings survive, there are usually entrances into the cross-halls from the ends of the verandas, as at Benwell and Chesters on Hadrian's Wall.Footnote 51 Entrances in this position are more often apparent in timber principia because of the spacing of the post-pits at the front of the cross-halls (cf. fig. 7). Doors opening off the verandas at either end of the cross-hall at Bainbridge would account for the two east–west passages; the passage connecting with their eastern ends would have provided access to the five rooms of the original rear range ( figs 10–11). These rooms had to be retained for some purpose, but the cross-hall was redundant and, probably following the removal of its roof, could be used for the new rooms, provided that there was still access to the rear range from the forecourt. The hypocausted room and the room to its north were presumably added after the original adaptations, as indicated by Hartley (see above), because they blocked the entrance to the north passage.

FIG. 10. The mid-Antonine principia probably as originally built; the positions of the forecourt entrance and veranda follow fig. 8, but are doubtful. Scale 1:250.

FIG. 11. The principia, partly converted into living accommodation (H = room with hypocaust). Scale 1:250.

The conversion added four rooms to the building, and then a further two. The hypocausted room suggests that the accommodation was for an officer above the level of an auxiliary-cohort centurion. Until the later third century, it is unusual to find hypocausts in the living areas of forts, except in praetoria. The remainder of the principia could have functioned much as before the conversion, with access from the forecourt to the rear range provided by the passages around the range of new rooms, though the removal of the cross-hall would have taken away the place of assembly in front of the tribunal and much reduced the size of the area from which ceremonies in the aedes could be witnessed (see below).

There are early and late parallels for the combination of principia and praetorium. In Augustan legionary fortresses, the aedes was located in the praetorium and could be approached through the rear range of the principia, both buildings having an axial relationship; this arrangement perhaps continued through the Tiberian period.Footnote 52 In small forts of the later third century and beyond, there is a type of building, described by Mackensen as principia cum praetorio, which combines, on a small scale, office space and living accommodation for the commanding officer.Footnote 53 At Bainbridge, the conversion of the principia surely signifies a drastic reduction in the size of the unit in occupation. This was presumably expected to be temporary: otherwise there would have been a corresponding reduction in the size of the fort. The praetorium and possibly many other buildings in the fort were perhaps in need of repairs, and the limited manpower was concentrated on making a few of the buildings habitable.

THE SIGNIFICANCE AND POSSIBLE HISTORICAL CONTEXTS OF THE CONVERSION OF THE MID-ANTONINE PRINCIPIA

The mid-Antonine principia, partly converted into accommodation, was swept away in c. a.d. 205 and replaced by entirely new principia. The date at which the conversion took place is uncertain, but might well have been only a short while before the complete rebuilding. Something very similar occurred in the principia at South Shields before the construction of the supply-base in c. a.d. 205–7 or 208–9:Footnote 54 the partition between two offices in the rear range was removed and the resulting space used for iron-smithing, while a timber building was inserted in the forecourt following the demolition of part of the veranda. At least one side of what was almost certainly the praetorium was also demolished and replaced by a smaller building, which in turn was superseded by one of the granaries of the original supply-base; the porta decumana went out of use and, probably also at this time, two other gates were partly or entirely blocked.Footnote 55

These various modifications to the buildings at Bainbridge and South Shields clearly indicate that the units occupying the forts had been greatly reduced in size, or even that they had been replaced by a small holding force drawn from another unit. At Bainbridge the officer in command was content with what, in comparison with a conventional praetorium, can be described as a small apartment. There is nothing to indicate that the conversion of the principia at South Shields included accommodation for an officer, but parts or all of the praetorium were demolished. The period of reduced occupation at these forts ended shortly before the Severan campaigns in Scotland, or at South Shields possibly during the preparations for the campaigns or during their early stages. The reduced occupation probably lasted only a few years; otherwise, as noted above, it might reasonably be expected that the forts would have been reduced in size to reflect the smaller numbers in the units. The period thus indicated might well have encompassed the battle at Lugdunum in a.d. 197, where Septimius Severus defeated Clodius Albinus, and its aftermath.Footnote 56 In one of his last studies of the Roman occupation of Brigantia, Hartley stated that ‘there are hints at such sites as Bainbridge and Ilkley that some of the barracks were occupied at the time of the destruction [in a.d. 196–7] and the implication is that small detachments had been left to look after the forts, but that they proved insufficient to deal with determined attacks by the natives’.Footnote 57 At South Shields, however, there were no signs of destruction in the very extensive excavations, published and unpublished, of the levels immediately preceding the building of the Severan supply-base, and at Bainbridge there were likewise no signs of destruction on the principia site. In recent decades, the possibility of widespread devastation in a.d. 196–7, when the northern peoples might have taken advantage of the removal of much of the Roman army to fight under Albinus at Lugdunum, has commonly been discounted.Footnote 58 Whether the forts had been ravaged by enemy attacks — which is most unlikely at South Shields — or merely required extensive renovations some forty years after they were built, involves a debate which can be side-stepped here. What needs to be explored is the significance of the reduced size of the units in occupation at the beginning of the Severan period.

That a large part of Albinus' army was drawn from Britain can hardly be doubted, though it is not confirmed by the ancient sources, but how soon after the slaughter at Lugdunum the British units on the losing side were brought up to strength is uncertain. For a few years it may have been necessary or politically expedient to keep the army in Britain much reduced in numbers. In the immediate aftermath of Lugdunum, repairs were made to buildings at Ilkley (RIB I, 637) and Bowes (RIB I, 730, preceding 3 May 198) under Virius Lupus, Severus' first governor in Britain. Both forts are on vital cross-country routes, and the inscriptions perhaps signify repairs to buildings essential to keeping lines of communication functioning properly rather than the overall renovation of these forts. The identity of the building at Ilkley is unknown, but at Bowes it was a baths building, ‘vi ignis exustum’ (‘burnt by the violence of fire’), that was restored. The latter might seem inessential if it was the fort baths, but the inscription might equally refer to the baths of a mansio (so-called) or posting-station, a vital facility at Bowes; the fort was on a major Roman road, now the A66 which is still sometimes closed in winter where it crosses Stainmore, immediately to the west of Bowes. The highly unusual circumstances of the building work, which was under the supervision of the prefect of the ala Vettonum at Binchester for the unit at Bowes, cohors I Thracum, finds no parallels elsewhere in Britain; the prefect of the cohort was absent and perhaps had been killed at Lugdunum, as Frere has recently suggested.Footnote 59 The only other building inscription of Virius Lupus from northern Britain is from the western legionary compound at Corbridge (RIB I, 1163), and is not associated with the forces holding Hadrian's Wall. Between the governorship of Virius Lupus and a.d. 205 (the date of the inscription at Bainbridge citing Pudens as governor), there was probably a gap of five or six years; the absence of building inscriptions, the usual source of governors' names in the second and third centuries, means that we do not know the name of the post-holder (possibly more than one) during that gap.Footnote 60 From c. a.d. 205–7 onwards, assuming that this was the period of Senecio's governorship, there is a large series of inscriptions from the forts on Hadrian's Wall and also in northern England generally.

An army well below full strength, in terms both of overall numbers and its cadre of commanders, certainly fits the circumstances at Bainbridge, South Shields and Bowes, and might also have caused the problems which brought Severus to northern Britain. However, from other excavated forts there are no signs of reduced occupation in the late second or early third century, with the exception of Vindolanda where much of the site of Stone Fort 1 seems to have been occupied by circular buildings. Buildings to the west are currently interpreted as a fort which co-existed with the circular buildings, but this is doubtful.Footnote 61 In many instances, the excavation of forts took place in the nineteenth or earlier twentieth centuries and has not recovered their detailed structural histories. Also, it is likely that at many forts a period of reduced occupation would not be detectable; after all, the virtual abandonment of the forts on Hadrian's Wall which is assumed during the Antonine advance into Scotland at present figures only in the absence or scarcity of early Antonine samian ware. Existing buildings could have been used by much reduced numbers, only requiring adaptation or demolition if they were in disrepair or had been destroyed, which seems to have been the case at Bainbridge and South Shields.

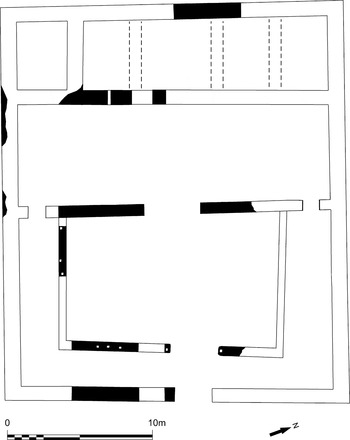

THE SEVERAN PRINCIPIA (FIG. 12)

The new building occupied approximately the same site as the Antonine principia, but only the front walls of the earlier and later forecourts coincided exactly. A false start, represented by two wide foundations, had been made on its construction; the foundations were probably part of the intended rear range ( figs 8 and 9, H). The central axis of the completed principia was c. 1.5 m farther north than that of the earlier building; the new building was c. 0.8 m wider north–south, but c. 3 m shorter east–west. The reduction in the overall depth of the building resulted from the comparative narrowness of the forecourt, the widths of the cross-hall and rear range being much the same as those of the Antonine principia. The overall dimensions of the principia were 24 m north–south by 24.5 m east–west. Its north–south walls were on the fort alignment, but the east–west walls were deliberately aligned about 5 degrees farther to the south-west.

FIG. 12. The Severan principia. Scale 1:250.

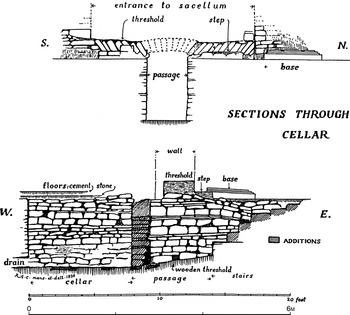

The cross-hall and rear rangeFootnote 62

The cross-hall measured 21.3 by 7.3 m internally. Its west wall survived to a maximum height of nine courses or 0.9 m, but its other three walls had been reduced to foundation level. The original floor was of mortar laid over a layer of brown clay, but it only survived along the west side of the cross-hall and near the entrance from the forecourt. The brown clay, sometimes mixed with pebbles and tile fragments, was a levelling layer over the western part of the site which sealed the walls of the original and altered Antonine principia ( fig. 9, L). The north side of the entrance from the forecourt was seen and, assuming it was centrally placed, allows its overall width to be restored as c. 2 m. The projecting foundation on the west face to the north of the entrance is shown on fig. 12 as of one build with the east wall of the cross-hall; a second foundation is restored in the equivalent position south of the entrance. However, a site plan seems to show the north foundation abutting the wall, and its north and south ends are ragged, as if it had extended farther in both directions.Footnote 63 It was perhaps a plinth or bench.

The tribunal, excavated in 1951, was in its customary position at the right-hand end of the cross-hall as approached from the forecourt. It measured 4.6 m east–west by 2.4 m north–south. Its south and east walls were 0.7 m in width; its west wall was 1.4 m wide and abutted the west wall of the cross-hall. This wider wall no doubt incorporated a flight of steps leading up to the tribunal, the floor of which was probably c. 2 m above that of the cross-hall. Under the raised floor, there was a room measuring 2.7 by 1.7 m. There was a gap at the north end of the east wall which might represent a door. Rooms under tribunals are known at several principia, including South Shields (in the mid-Antonine and late third- or early fourth-century principia), Chesters and Carpow.Footnote 64 In principia without strongrooms, as at Chesters (assuming the tribunal to have been original and the strongroom to have been a much later addition), at Carpow, and in the mid-Antonine principia at South Shields, it is assumed that the room under the tribunal, which at South Shields took the form of a semi-basement, was built for the storage of bullion and valuables, as first suggested by R. Birley in his report on Carpow.Footnote 65 The later principia at South Shields also included a very large strongroom under the aedes, which the present writer suggested was for the storage of bullion in transit through the supply-base, while the room under the tribunal was for the unit's valuables.Footnote 66 A similar explanation can be proposed for Bainbridge, where the funds of the unit and other valuables might have been stored separately. The surface of the west cross-hall wall abutted by the tribunal was plastered, implying that the latter was built after the shell of the building was completed, but not that the tribunal was built at a much later date. To the east of the tribunal were the foundations of two steps, which were probably later additions. They cannot have extended up to the original height of the tribunal and were probably associated with a rebuilding which reduced its level.

North of the entrance to the aedes, a sandstone statue base ( fig. 13) was found in 1926 and was described by Collingwood as follows: ‘… a base 4 ft. [1.22 m] by 3 ft. 6 in. [1.07 m], consisting of a single stone with mouldings round three sides … it had a dowel-hole in the middle, and in front two T-shaped cramp-holes, in one of which a bronze cramp, leaded in and broken off short at the base of the T, was still in place. This had evidently served as a stand either for an altar or for a statue, probably the latter, because it does not appear that altars were cramped into their bases, a precaution which would be more necessary in the case of a statue. There is no base symmetrically disposed to the south of the steps; presumably this represents an imperial statue … auspiciously placed on the right hand of one entering the sacellum [or aedes].’Footnote 67 Hartley's excavations confirmed that there had not been another statue base south of the aedes. In front of the aedes were one or two steps leading up to the threshold, which was 0.37 m above the level of the cross-hall floor.Footnote 68 However, the original floor in the aedes was at the same level as that in the cross-hall, which might suggest that the threshold was not part of the original construction and was inserted at the same time as a later floor, perhaps of timber, at a higher level.

FIG. 13. The statue base placed against the west wall of the Severan cross-hall; foreground, fragments of the paving associated with the late Roman timber building; drain cutting through party wall of northern two rooms inserted in mid-Antonine cross-hall. Scale divisions in feet.

In the rear range, all five rooms measured 4.8 m internally east–west; the aedes (Room 3) was 5.25 m in width, Rooms 1, 2 and 4 were 3.5 m in width, and Room 5 3.8 m in width. The central three rooms opened onto the cross-hall: the aedes opening was 3.5 m in width, but that of Room 2 was only 2 m in width; the width of the opening in Room 4 is uncertain. There were doors 1 m in width between Rooms 1 and 2 and between Rooms 4 and 5. The floors in all five rooms were originally of mortar. There are full descriptions of the aedes and its strongroom by Collingwood and of Room 5 by Wade, which do not need to be repeated here, although Collingwood's plan and elevation of the strongroom are reproduced as fig. 14.Footnote 69 Painted wall-plaster fragments from late deposits in these rooms are unlikely to represent their original decorative schemes and are described in the subsequent section dealing with the later occupation of the rear range.

FIG. 14. The Severan aedes and strongroom (after Collingwood 1928, fig. 4 ). Scale 1:75.

The forecourtFootnote 70

Its dimensions were 21.3 by 8.9 m internally. The south side of the east entrance was seen and established its width as 1.9 m. The supports for the veranda roofs were represented by eleven foundations of mortared rubble c. 0.9 m square. They were spaced unevenly; on the east side of the forecourt, there were three south of the entrance and four to the north. The builders were apparently unable to find a way of fitting the veranda supports neatly into the forecourt with its plan in the form of a parallelogram. The central and west foundations on the north side appear on an unpublished section: the former was 0.63 m in depth, and the latter rather deeper, at 0.85 m, because it was cut through the filling of the so-called demolition pit.Footnote 71 The foundations presumably supported the square bases with chamfered sides which were reused when the verandas north of the entrance were rebuilt ( fig. 15). The floors of the verandas were of mortar, and the forecourt had a gravel surface, in places with a few paving stones which might have represented later patching.

FIG. 15. Chamfered blocks forming the bases of the northern veranda supports in the Severan forecourt, looking east (67 HV). The blocks were re-positioned following the subsidence and collapse of the eastern forecourt wall where it crossed the filling of the probable water-tank; further signs of subsidence can be seen at the top of the photograph. Ranging rods with one-foot divisions; smaller scales with division in inches.

Three foundations projected from the east face of the cross-hall wall. The south foundation was 1.3 m in length and 0.45 m in width; notes state that it was built against the wall, but that does not necessarily mean that it was not part of the original building programme. The foundation immediately north of the entrance was 1.8 m in length and also abutted the foundations of the cross-hall wall; its north and south ends were ragged. The excavation records refer to these projecting foundations as pilaster bases. This is not a plausible interpretation of their purpose: their spacing is uneven, and one is of a much greater length than the others. One possibility is that they were benches or platforms to support altars, reliefs or aediculae.Footnote 72

Dating evidence

Hartley connected the construction of the principia with the general rebuilding of the fort in c. a.d. 205–7 with which the three inscriptions erected by the prefect L. Vinicius Pius are associated (see below). The latest pottery from the construction levels of the principia or from activities preceding them is consistent with a Severan construction date:

64 EII, 14, described on the finds card as above Antonine and below Severan forecourt levels: form 31R, stamp 3a of Pottacus (CG, a.d. 160–200).

67 GVII, 26, from the robber trench of the west wall of the Antonine principia: late second- to early third-century group including a BB2 bowl or dish with a rounded rim and a form 37 in the style of the late Antonine potter Paternus v.

67 HV, 28, ‘demolition pit’, lower filling: form 33, stamp 4a of Mascellio i (CG, a.d. 160–200):Footnote 73 the same layer contained a sherd from a ‘colour-coated scroll beaker’, presumably Nene Valley colour-coated ware, which is not known on Hadrian's Wall before the Severan period, but which could possibly have reached forts further south a little earlier.

67 HV, 20, ‘demolition pit’, upper filling: Antonine samian ware and a Lezoux colour-coated base, no earlier than the late second century.

The Severan building inscriptions

The three building inscriptions already referred to are by far the most important evidence for an extensive Severan reconstruction of the fort. Two (RIB I, 722–3) were found shortly before the end of the sixteenth century. They were recorded by Camden shortly after their discovery, but were lost by the early eighteenth century. The third (RIB III, 3215) was found by Hartley in 1960 outside the Severan east gate, lying face downwards. The back of the slab had been exposed in Collingwood's excavations.Footnote 74 The inscriptions have been published in volumes I and III of Roman Inscriptions of Britain, but the readings of the two earlier finds were revised in the Addenda and Corrigenda to RIB I in the light of the inscription discovered in 1960. The texts of all three are given below.

RIB I, 722 + add. (cf. Birley, A.R., Reference Birley2005, 188–9)

Imp(eratori) Caesari L(ucio) Septimio [Severo]|Pio Pert[i]naci Augu[sto et]|imp(eratori) Caesari M(arco) Aurelio A[ntonino]|Pio Feli[ci] Augusto et P(ublio) S[eptimio|Getae nobilissimo Caesari vallum cum]|bracchio caementicium [fecit coh(ors)]|VI Nervio[ru]m sub cura L(uci) A[lfeni]|Senecion[is] amplissimi [co(n)s(ularis) institit]|operi L(ucius) Vin[ici]us Pius praef(ectus) [coh(ortis) eius(dem) Sen]|ecio[ne et Aemiliano co(n)s(ulibus)]

For the Emperor Caesar Lucius Septimius Severus Pius Pertinax Augustus and for the Emperor Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus and for Publius Septimius Geta, most noble Caesar, the Sixth Cohort of Nervians built this [rampart] of uncoursed masonry with annexe-wall under the charge of Lucius Alfenus Senecio, senator of consular rank; Lucius Vinicius Pius, prefect of the cohort, had direction of the work (in the consulship of Senecio and Aemilianus [a.d. 206]?).

RIB I, 723 + add. (cf. Birley, A.R., Reference Birley2005, 189)

[Imp(eratori)] Caesari Augusto […|Marci Aurelii filio […|…sub cura L(uci) Alfeni]|Sen[ec]ionis amplissimi [co(n)s(ularis) coh(ors) VI Nerviorum|fecit cui praeest L(ucius]) Vinic[ius] Pius [praef(ectus) coh(ortis) eiusd(em)]

For the Emperor Caesar Augustus … son of Marcus Aurelius … under the charge of Lucius Alfenus Senecio, senator of consular rank, the Sixth Cohort of Nervians built this under Lucius Vinicius Pius, prefect of this unit.

RIB III, 3215

Imp(eratori) Caesari Lucio Septimio|Severo Pio Pertinaci Aug(usto) et|imp(eratori) Caesari M(arco) Aurelio|Antonino Pio Felici Aug(usto) et|P(ublio) Getae no|[[bilissimo Caesari d(ominis)]]|n(ostris) imp(eratore) Antonino II et|Geta Caesare co(n)s(ulibus) centuriam|sub cura G(ai) Valeri Pudentis|amplissimi co(n)sularis coh(ors)|VI Nervior(um) fecit cui praeest|L(ucius) Vinicius Pius praef(ectus) coh(ortis) eiusd(em)

For the Emperor Caesar Lucius Septimius Severus Pius Pertinax Augustus, and for the Emperor Caesar Marcus Aurelius Antoninus Pius Felix Augustus, and for Publius Septimius Geta most noble Caesar, in the consulship of Our (two) Lords the Emperor Antoninus for the second time and Geta Caesar [a.d. 205]; the Sixth Cohort of Nervians which Lucius Vinicius Pius, prefect of the said cohort, commands, built (this) barrack-block, under the charge of Gaius Valerius Pudens, senator of consular rank.

The consular date given in RIB III, 3215 is a.d. 205 and is the only epigraphic evidence for the date of Pudens' governorship. Alföldy thought it likely that the last line of RIB I, 722 also gave a consular date but could suggest nothing that would have included the remaining letters, which were ‘E’ (or ‘F’) CIO; however, A.R. Birley suggested Albinus and Aemilianus, consuls in a.d. 206, the first cited by another of his cognomina — Senecio — to avoid evoking the unpleasant memory of Severus' rival, Clodius Albinus.Footnote 75 The governor cited in this inscription and in RIB I, 723 was L. Alfenus Senecio, known from another inscription, at Risingham (RIB I, 1234 + add.), to have held this post at some date between a.d. 205 and 207. Epigraphically, there is nothing otherwise to suggest when during the joint reign of Severus and Caracalla he was governor of Britain, but the restoration of the consular date of a.d. 206 supports the view, originating with the discovery of RIB III, 3215 in 1960, that Pudens' governorship preceded Senecio's.Footnote 76 In any event, the building programme overseen by L. Vinicius Pius, prefect of cohors VI Nerviorum, overlapped two governorships.

Camden gives some details about the discovery of RIB I, 723: ‘… not long since there were digged up the statue of Aurelius Commodus the Emperor … he was portraied in the habite of Hercules, and his right hand armed with a club, under which there lay, as I have heard such a mangled inscription as this [text given], broken heere and there with void places betweene: the draught whereof was badly taken out, and before I came hither was utterly spoiled … this was to be seen in Nappa [Hall] …’.Footnote 77 The statue was taken by Birley and Richmond to have represented Maximinianus Herculis in the guise of Hercules and to have stood on the inscription which had been reused as a flagstone in the principia.Footnote 78 This reads far too much into Camden's description, which only places the find at the Roman site of Bainbridge and states that the statue was on top of the inscription; both could have been built into the wall of some later building.

Five ‘pila-tiles’ stamped ‘IMP’, with all three letters ligatured, were found in 1957 in the make-up for a late rebuilding of the barracks in the praetentura (RIB II.5, 2483, i–v). No mention of them was made in the publication of that excavation, but details of their context are given in the ‘Deposits’ book for 1957–59.Footnote 79 They were found in a layer of clay together with fragments of roofing- and box-tile, debris removed from a hypocausted room probably in the praetorium or fort baths; the layer in which they were found seems to have been part of the clay packing that preceded the building of the Theodosian or late fourth-century barracks.Footnote 80 Tiles with very similar stamps, though probably not from the same die, are also known from Carlisle and Housesteads; Swan associated them with Severan building programmes.Footnote 81

THE BAINBRIDGE PRINCIPIA: DISCUSSION

The plans of the principia

The three successive principia at Bainbridge — Flavian, mid-Antonine and Severan — are instructive additions to the corpus of such buildings from auxiliary forts.Footnote 82 Of all the frontier provinces, Britain has produced the largest collection of complete and well-dated principia plans, but they are dominated by two groups, one from the forts on Hadrian's Wall and the other from the Antonine Wall. There is also a small Flavian group of timber principia. The detailed plans of the principia not forming part of these three groups seem to be heterogeneous, though they display some general developments, touched on below, which probably resulted from changes in ceremonial activities.