INTRODUCTION

Hadrian's Wall was the most elaborate of all the frontier works that protected the Roman empire, and in recent years its overall significance has become more widely appreciated, not least as an example of engineering on a grand scale. Half a century ago it could be described as essentially ‘a police barrier’, seemingly not of much interest beyond the field of frontier studies ‘because the Roman empire added little to the science of military architecture as such’.Footnote 1 Hadrian's project is now seen as an example of ‘exceptional construction’, worth considering alongside the greatest Roman buildings in the Mediterranean world.Footnote 2 Its importance is not lessened by its military character. The Wall was just one of a series of enormous projects ordered by the emperor.Footnote 3 Each was quite different, but the Wall is of special interest because of its complex sequence of construction, which has a great deal of contemporary documentation. Building inscriptions and over 200 centurial stones have been used, together with detailed analyses of the structural remains, in many attempts to reconstruct the order of works. Some elements are incontestable, for example the progression from Broad to Narrow Wall, but much remains uncertain. Detailed knowledge of the Wall curtain, turrets and milecastles depends largely on research undertaken between the 1920s and the 1950s. These problem-solving campaigns undertaken by Birley, Richmond, Simpson and Swinbank belong to bolder times, and for the most part new theories can only be tested against old evidence.

It is mainly the forts and their environs that have produced new information: ten in the Wall zone have seen large-scale excavations in the last half-century for reasons that range from research to work in advance of modern development, and at seven there have been geophysical surveys, most of which have been extensive. Other information of equal importance has come from the investigation of rural settlements beyond and behind the Wall in north-east England where, as a result of developer-funded archaeology in the last 20 years, the effects of Roman frontier policies have become more obvious.Footnote 4

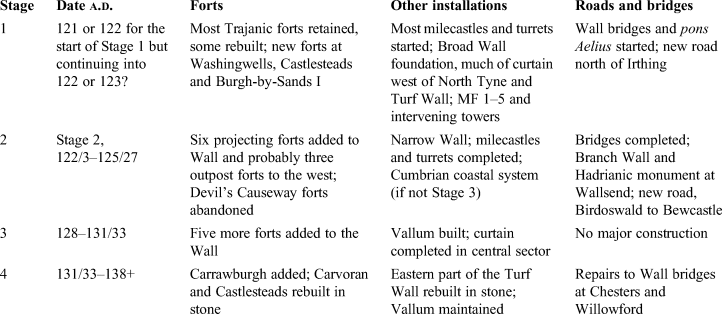

In what follows, the results of this more recent work will be used to look at the original scheme for the Wall and the modifications and improvements made to it during Hadrian's reign. At first the Trajanic forts on the Stanegate (the road between Corbridge and Carlisle) with a few additions were to have controlled the Wall, which ran to their north; in front of the eastern flank of the Wall, the Trajanic frontier on the Devil's Causeway was still held. Forts were then added to the line of the Wall (the fort decision), and it is proposed that they were built in three stages, the first two of which also involved major redeployments of forces north and south of the Wall. After the first stage, large parts of the original scheme operated for rather longer than was previously apparent. The various transformations of the defensive works, in their strength and extent, justify reference to Hadrian's northern British frontiers in the plural.

Detailed studies of the Wall have recently concentrated on the building programme especially as it relates to the curtain, milecastles, turrets and the Vallum, and have reached varying conclusions.Footnote 5 The wider background to the questions discussed in this paper are provided by general accounts recently published by Nick Hodgson, David Breeze and Matt Symonds.Footnote 6 The new scheme proposed here relies mainly on the structural history of forts and their relationships to the Wall curtain and Vallum. Some aspects of these histories and relationships are matters for debate, some have been neglected and others need to be reassessed because of recent or unpublished discoveries. It has therefore been necessary to examine some sites in detail, but most of these analyses are placed in the Supplementary Material together with bibliographical references relevant to the discussion of other forts in the main text. Some of the analyses must be regarded as interim, pending the fuller publication of recent or much older discoveries. Also relevant to the sequence of construction is the pottery. In particular, the potential of samian ware to establish the earlier chronology of the Wall forts has hitherto not been explored systematically. The Supplementary Material includes lists of the relevant finds together with detailed discussion. Again, this study must be regarded as interim, although some of its results, such as the late dating of the fort at Housesteads, can be regarded as robust.

The overall emphasis in the main text is on presenting a building programme for the Wall based on structural sequences, building inscriptions and the dating of pottery. Some of the wider historical implications are noted briefly, but a comprehensive overview is beyond the scope of this paper.

THE PLACE OF FORTS IN THE BUILDING PROGRAMME

Before analysing the original scheme for the Wall, the reality of its first major revision needs to be considered. This was the decision to place forts on the Wall only after its construction had begun and in places was nearly complete. In 1938, Ian Richmond stated that forts had actually been intended as part of the original scheme and that the Wall had been built across their intended sites because of ‘a lack of co-ordination’. By 1950, turrets and milecastles had also been found under the forts which Richmond then accepted were part of a second scheme.Footnote 7 Doubts about the fort decision were revived by Jim Crow on the grounds that between Willowford and Irthington the Wall was cut off from the Stanegate and its forts by the River Irthing and that there were no pre-existing forts east of Corbridge and north of the River Tyne to support the Wall.Footnote 8 Both points will be discussed later, but it has to be acknowledged that the absence of such pre-existing forts is practically impossible to prove, though it is highly probable. Beyond the suburbs of Newcastle, most of the area in question is still agricultural and has been well explored by antiquaries and archaeologists. There are, moreover, no definite signs of an extension of the Stanegate along the north side of the Tyne Valley, not even a medieval road following straight alignments conceivably of Roman origin.Footnote 9

The strongest argument for the fort decision is the order of works on the Antonine Wall and at later stages in the building of Hadrian's Wall. On the Antonine Wall, work at Balmuildy, Castlecary and Old Kilpatrick is known to have been in hand before the curtain was started, at least in their vicinity.Footnote 10 Until recently, these forts, together with three others, were generally regarded as primary, with more forts, mostly smaller, added later; this view is no longer held by all, but has been convincingly justified by Hanson.Footnote 11 At Balmuildy there were stone wing walls which suggest that in the original scheme the Antonine Wall was also intended to have been of stone throughout.Footnote 12 This fort must have been started before work began on the Wall and also on the fortlets, all of which were built in turf. On Hadrian's Wall the projecting fort at Wallsend was provided with a long wing wall to accommodate the Narrow Wall extension from Newcastle; the fort was almost certainly earlier than the curtain running west to Newcastle, because the wing wall was constructed of large blocks in a rough version of opus quadratum, whereas the remainder of the curtain reverted to the conventional techniques for building the Wall.Footnote 13 At Housesteads, built in a sector where previously only the Broad foundations of the curtain had been laid, the Wall was completed after the fort, while at Great Chesters the Narrow Wall, perhaps in the form of a wing wall, was bonded with the fort at its north-west corner.

The priority of all these forts is accounted for by the need for security. Even if not ready for the units intended to occupy them in the long term, the forts would be strong points as soon as their defensive circuits were complete, supplementing the protection for the Wall-builders and their supplies provided by the temporary labour camps.Footnote 14 Where the building of forts involved demolition of the curtain and minor installations, that can only have been because an original scheme had been revised. If it had always been intended to have forts on the line of the Wall, they would have been built before the curtain.

THE TRAJANIC FRONTIER AND THE ORIGINAL SCHEME FOR THE WALL IN THE EAST

In c. a.d. 105 part of the Roman army was withdrawn from Britain, and the lowlands of Scotland were abandoned. The Tyne–Solway isthmus, or at least its western and central parts, now represented the northern frontier of the province.Footnote 15 There were already forts in this area, the most important being those at Carlisle and Corbridge, which were on the two main roads connecting the frontier zone with southern Britain. More forts together with at least two small forts or fortlets and four towers were added to the west of Corbridge, completing the western and central parts of the frontier system that was still operating at the beginning of Hadrian's reign (fig. 1). There are no signs of a continuation of this system eastwards to the lowest reaches of the Tyne, and this led R.G. Collingwood to suggest that the Stanegate limes ‘may possibly have followed the road known as the Devil's Causeway to near Berwick-on-Tweed; but until the course of this road has been explored with the spade this must remain mere guesswork’.Footnote 16 The route started at Corbridge, following the line of Dere Street for 6 km before the Devil's Causeway branched off to the north-east. For most of its length of some 87 km, this road skirted the western edge of the Northumberland coastal plain, perhaps ending on the south side of the River Tweed at Tweedmouth (fig. 2).Footnote 17 More than 30 years elapsed until Collingwood's idea briefly saw the light of day again, and a further 42 years before it was finally disinterred by Hodgson.Footnote 18 In the 1930s no military sites were known along the Devil's Causeway, but a fort was subsequently found at Low Learchild from which there was pottery dating to the first and second centuries a.d. The existence of another fort at Wooperton is indicated by finds of large quantities of pottery, none necessarily as late as the Hadrianic period. Finally, earthworks at Longshaws, 3.4 km east of the Devil's Causeway, have been identified as a fortlet of Flavian type with an adjacent enclosure possibly of later date, and marching camps have been recorded near the road by aerial photography (see table 1, below).Footnote 19 Developer-funded excavations have shown that the coastal plain to the east of the Devil's Causeway was densely occupied in the later Iron Age, characteristically by settlements in large ditched enclosures, though there were also open settlements.Footnote 20 These sites remained in occupation until the Hadrianic period or perhaps a little later, when they were abandoned or in a few instances replaced by enclosures of a different character. A frontier along the Devil's Causeway would have protected this productive agricultural area from depredations coming from the zones to the west and north which the Roman army had given up in c. a.d. 105.

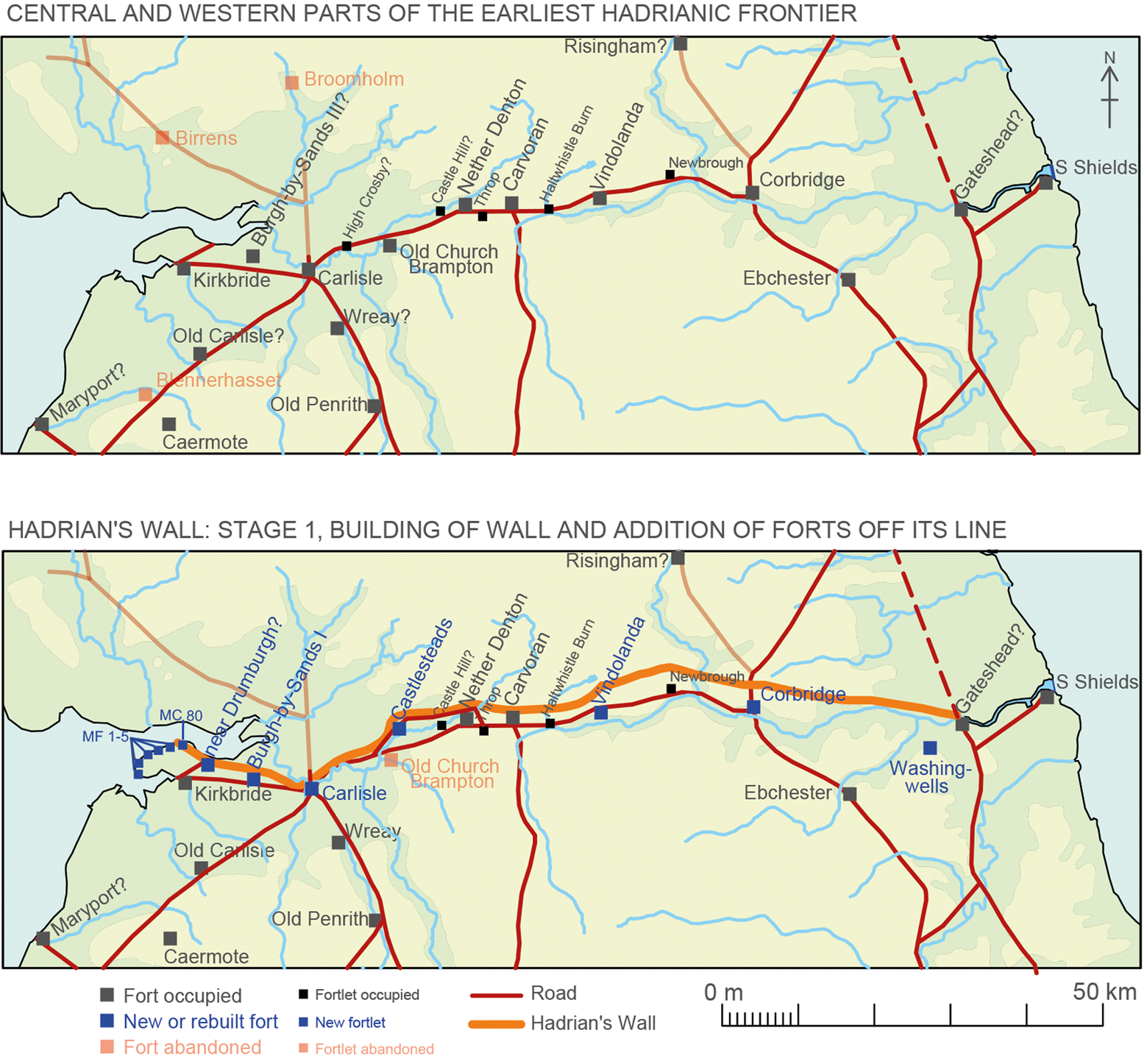

FIG. 1. Part of the northern British frontier works: their state at the beginning of Hadrian's reign and in Stage 1 of his Wall (source: author).

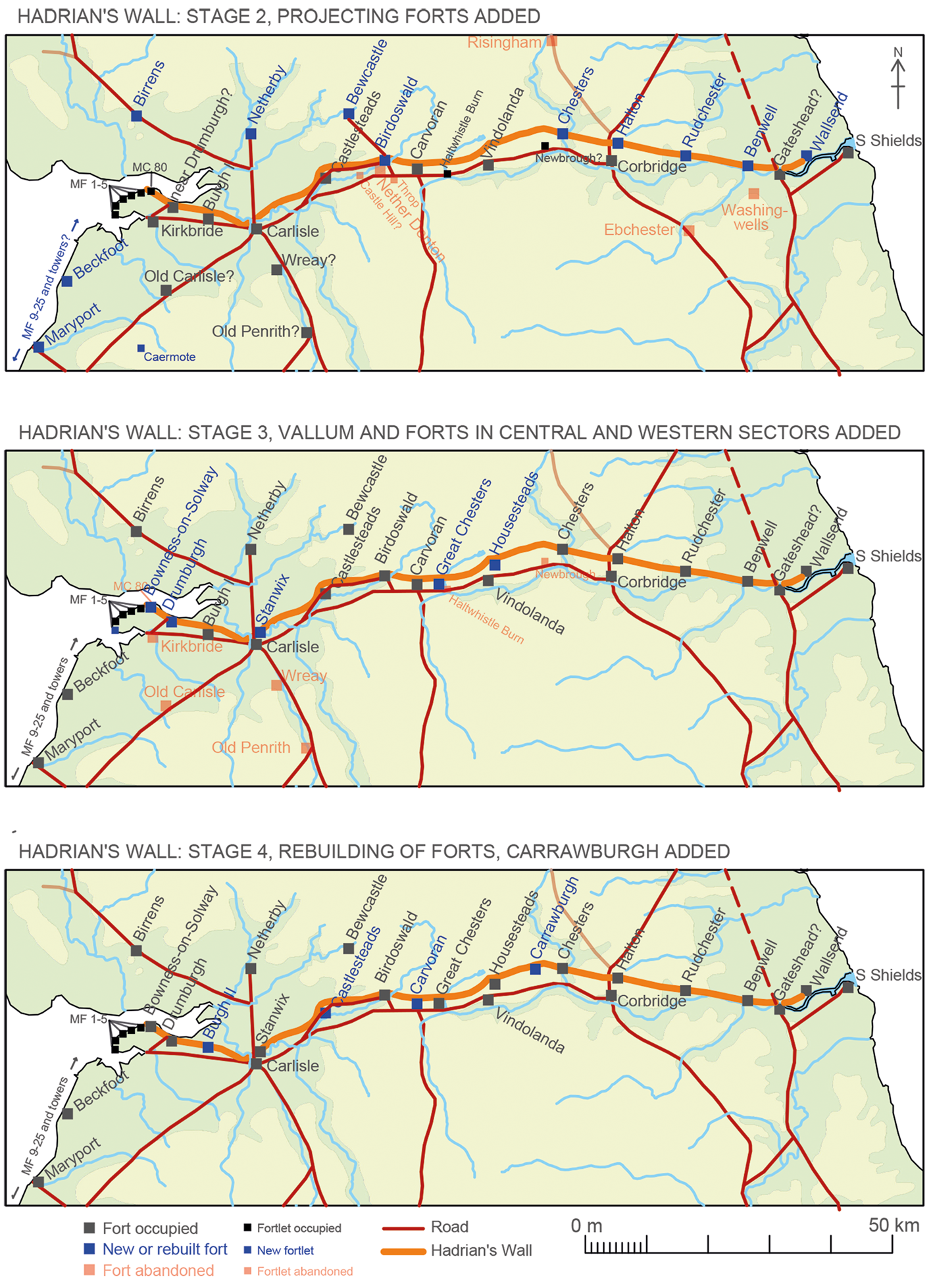

FIG. 2. The Devil's Causeway and Hadrian's Wall in Stage 1 (source: author).

Table 1 forts and fortlets supporting hadrian's wall in stage 1

In the original scheme for the Wall, the Stanegate forts were retained to deal with threats to the frontier and to provide men for the milecastles and turrets. Assuming that no such forts still remain to be found between Corbridge and the Tyne crossing at Newcastle, which are 26 km apart, the way in which the Wall was supported in this area clearly differed from the system elsewhere. Detachments from Corbridge, the Tyneside forts (discussed below) and even hinterland forts such as Ebchester could have manned the smaller installations, but this eastern stretch of the Wall would have lacked the immediate reinforcement which closely spaced forts and fortlets behind its line provided to the west. The possible reasons for this difference need to be considered together with another question: why did the Wall end at Newcastle, 12 km from the mouth of the Tyne in a direct line, or 16 km following the course of the river?Footnote 21 At its western end the Wall ran for 9 km beside the tidal flats, beyond the point where the Eden flows into the Solway Firth, to its termination at or just beyond MC 80 (fig. 1, STAGE 1).

The arrangements at the eastern end of the Wall would be explained by the retention of the Devil's Causeway and its forts as part of the new frontier system. Although longer than the road between Corbridge and Kirkbride (87 km as opposed to 78 km), the Devil's Causeway had fewer military installations on its line, though more probably remain to be found, and there is a hint of a fort at Gloster Hill near the mouth of the River Coquet. The Iron Age settlements on the Northumberland coastal plain are notable for their large size and the ‘monumental scale’ of the earthworks that enclosed them.Footnote 22 The main purpose of these banks and ditches, built in the later pre-Roman Iron Age, was no doubt to ‘express the status, wealth and power of [their] occupants’, but they were also a serviceable defence against attackers. During the Trajanic period, the people of these settlements might have become foederati in a treaty relationship with Rome, using their fortified farmsteads to supplement Roman control of their territory.Footnote 23 In the later Roman period there seems to have been a similar degree of co-operation between the army and ‘native Libyan potentates’ in Tripolitania, where the defended farms (gsur) would have contributed to the security of the frontier areas of the province.Footnote 24

Together with the settlements it protected on the southern part of the coastal plain, the road represented a deep zone of control north of the Wall. The Wall ended well within the protected zone at Newcastle, where there was an ancient crossing of the Tyne connected with a pre-existing Roman road running southwards.Footnote 25 The sector of the Wall east of Corbridge would have been a backstop, and in normal conditions could have been lightly held, the area to the north acting as a buffer zone which could delay any large-scale incursion long enough to reinforce the Wall and amass the forces necessary for a counterattack.

A further possibility is that the main axis of the frontier beyond the Wall was moved from the southernmost part of the Devil's Causeway to a road running north from Newcastle.Footnote 26 This change would have shortened the lines of communication. It would also explain a concentration of forces near the Tyne crossing. Circumstantial evidence suggests that there was already a fort at Gateshead on the south bank of the river, though it is yet to be found. The road running south from the crossing was connected by the Wrekendike to South Shields at the mouth of the Tyne where occupation under Hadrian is certain, is probable under Trajan and might have begun even earlier. A third fort is situated at Washingwells, south of the Tyne and 4.5 km south-east of Gateshead. Its ditches enclose an irregular quadrilateral of about 2.6 ha and perhaps a little more, making it as large as the fort at Corbridge. The apparent absence of internal buildings might mean that the site was abandoned at an early stage in its construction; there is no dating evidence, but work on the fort might have ended when the original scheme for the Wall was revised.Footnote 27 The fort overlooked the Team valley and the lowlands to the east, and although the line of the Wall 4.5 km immediately to the north would not have been in sight, there would have been a clear view of Gateshead, the crossing of the Tyne and the final Wall mile.

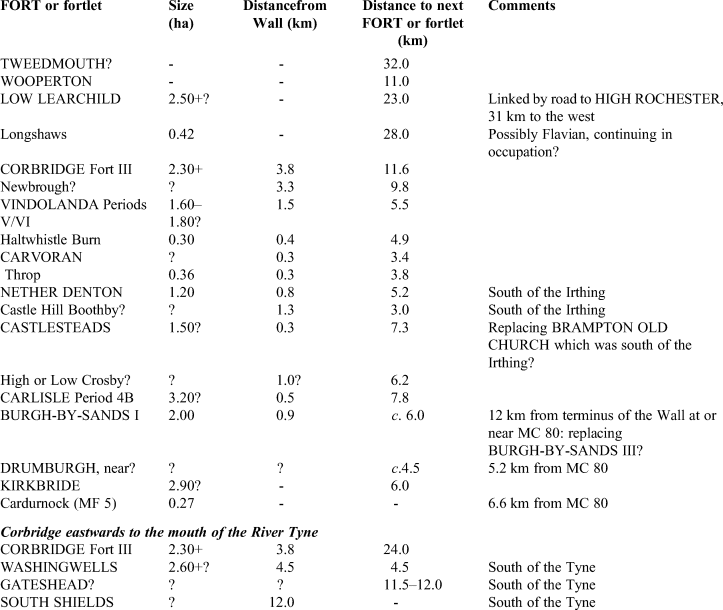

The eastern part of the Antonine Wall supplies an instructive comparison with the initial arrangements proposed for the eastern part of Hadrian's Wall (fig. 3). From the fortlet at Watling Lodge a road ran north to Bertha, a large fort (c. 3.9 ha) some 50 km from the Antonine Wall. Along the course of this road were three other forts: Camelon (2.9 ha), Ardoch (3.2 ha) and Strageath (1.8 ha). Once taken to have been part of an ‘offensive–defensive’ system, with their connecting road ‘keeping open what would serve as an easy line of advance’,Footnote 28 the forts are now seen as a cordon between the Forth and the Tay which isolated and protected the Fife peninsula.Footnote 29 In return, the leaders of the population in the peninsula might have been expected to keep an eye on the approaches to the eastern end of the Wall and, beyond it, the northern shore of the Forth, especially west of the fort at Cramond where the firth is narrow. As on Hadrian's Wall, alliances, willingly made or imposed, were likely to have been an element in the system of frontier control, but the difference was that the eastern part of the Antonine Wall was held in greater strength than the corresponding part of its predecessor was at first. Even so, three of the four forts on the road running north to Bertha were all larger than those on the Antonine Wall, whether primary or secondary, except for Mumrills which had an area of 2.6 ha. In the east the primary line of control was along the road to the north, and the Wall served as a backstop. The same is true of the eastern part of Hadrian's Wall in the original scheme, even if the forces along the Devil's Causeway were fewer than in Fife.

FIG. 3. The eastern part of the Antonine Wall and the road north (source: author).

FORTS IN THE ORIGINAL SCHEME FOR THE WALL: STAGE 1

The Stanegate began at Corbridge, where the fort was rebuilt in the early Hadrianic period. It occupied a crucial position, commanding the point where Dere Street crossed the Tyne and the start of the extension of the Trajanic frontier which was carried north-eastwards along the Devil's Causeway (fig. 1, STAGE 1; table 1). The next fort known to the west is Vindolanda, likewise rebuilt in the early Hadrianic period, but it is 21 km from Corbridge, not far short of the distance between Corbridge and the eastern end of the Wall. A small fort dating to the later Roman period is known at Newbrough, 11.6 km west of Corbridge, and there are slight indications that it had succeeded an earlier fort or fortlet. Eric Birley's reconstruction of the Stanegate system required a fortlet at Grindon Hill, 6.1 km east of Vindolanda, on the grounds of spacing.Footnote 30 His reconstruction also required another east of the North Tyne at Wall,Footnote 31 but neither there nor at Grindon Hill is there any evidence for these fortlets. In the face of these uncertainties, it is worth considering whether the arrangements east of Corbridge extended as far west as Vindolanda. There were extensive settlements in Redesdale and North Tynedale. Though only a small number have been excavated, many are likely to have been occupied in the Roman period, even if they originated in earlier times.Footnote 32 In the pre-Hadrianic period Redesdale was controlled by forts on Dere Street at High Rochester and Blakehope, but from neither site are there enough finds to establish their early history in any detail. High Rochester and Low Learchild on the Devil's Causeway were connected by a road and at some stage must have been held simultaneously. The fort at Risingham was situated in the lower part of Redesdale, only 5.5 km north-east of the meeting of the Rede and the North Tyne. Early levels at the fort remain almost entirely uninvestigated, but it was possibly occupied in the Trajanic and early Hadrianic period,Footnote 33 exercising control over at least parts of the North Tyne valley.

We are on firmer ground at Vindolanda and further to the west. It is argued in the Supplementary Material that the Periods V/VI fort at Vindolanda, probably with an area of c. 1.6–1.8 ha, was earlier Hadrianic and the source of a fragment from a building inscription (RIB 1702) contemporaneous with the original scheme for the Wall. The nearest milecastles to the fort are at Hot Bank (38) and Castle Nick (39), and from the former are two complete inscriptions (RIB 1637–8) carrying the name of A. Platorius Nepos, governor in c. a.d. 122–125/7. The Vindolanda inscription is a fragment, but its surviving three lines are nearly identical to those of the other two, and all three inscriptions were probably cut by the same hand; the missing line on the Vindolanda would have included the governor's name, surely that of Nepos.Footnote 34 The fortlet at Haltwhistle Burn, where pottery demonstrates occupation continuing into the early Hadrianic period, lies 5.5 km west of Vindolanda. At Carvoran, 4.9 km further to the west, there was a fort with an area of 1.65 ha, built in stone in c. a.d. 136–8 by cohors I Hamiorum, and there is evidence for an earlier fort on the site. Throp, 3.4 km west of Carvoran, is another fortlet where occupation continued into the early Hadrianic period.

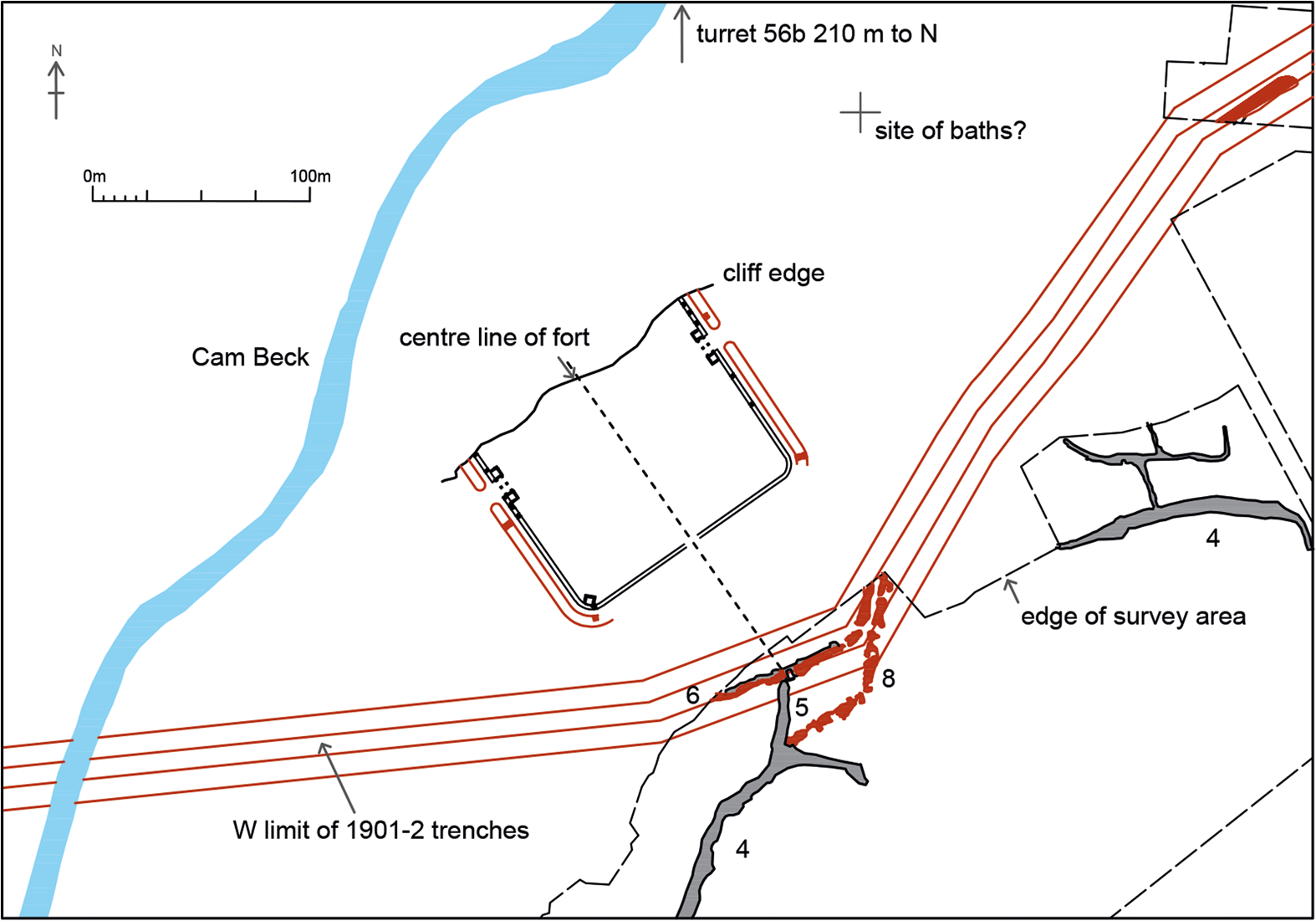

About 1 km from Throp, the Wall crossed the Irthing at Willowford by means of a bridge which originally took the Wall-top walk across the river. Beyond this point, the river separated the Stanegate from the Wall. The next fort to the west was at Nether Denton, 3.8 km from Throp; the fort is of some complexity and appears to have had an earlier and larger predecessor. The small quantities of pottery from the site include one samian bowl of Hadrianic to early Antonine date. The Irthing lies to the north of the fort, though there is a modern ford nearby; the ascent to the Wall above the valley is very steep. There is a fort or fortlet at Castle Hill, Boothby, 5.2 km to the west, and 3 km beyond this site two forts at Brampton Old Church and Castlesteads. Whether Brampton remained in occupation after Trajan, if only briefly, is uncertain, but like Nether Denton and Boothby it was cut off from the Wall by the river and might well have been replaced by Castlesteads. The stone fort, with an estimated area of 1.5 ha, was sited 1 km north of the river and had succeeded an earlier fort in turf and timber and of unknown extent. An inscription probably of c. a.d.136–8 can be plausibly connected with the replacement in stone of this earlier fort.Footnote 35 A geophysical survey at Castlesteads has confirmed that there was a road north of the Irthing which presumably branched off the Stanegate near Irthington and ran as far east as Willowford (see figure 7).Footnote 36 The part of the Wall between Willowford and Castlesteads that was isolated from the Stanegate was only c. 12 km in length, and to its south there were frequent fords across the Irthing in the post-medieval period, and presumably earlier.Footnote 37 Nether Denton lay only 0.9 km south of the Wall, and though separated from it by the Irthing, could easily have supported the turrets and milecastles in this sector.Footnote 38 Nevertheless, when the river was in spate, by no means a rare event, a road on its north side would have ensured the security of this part of the Wall.

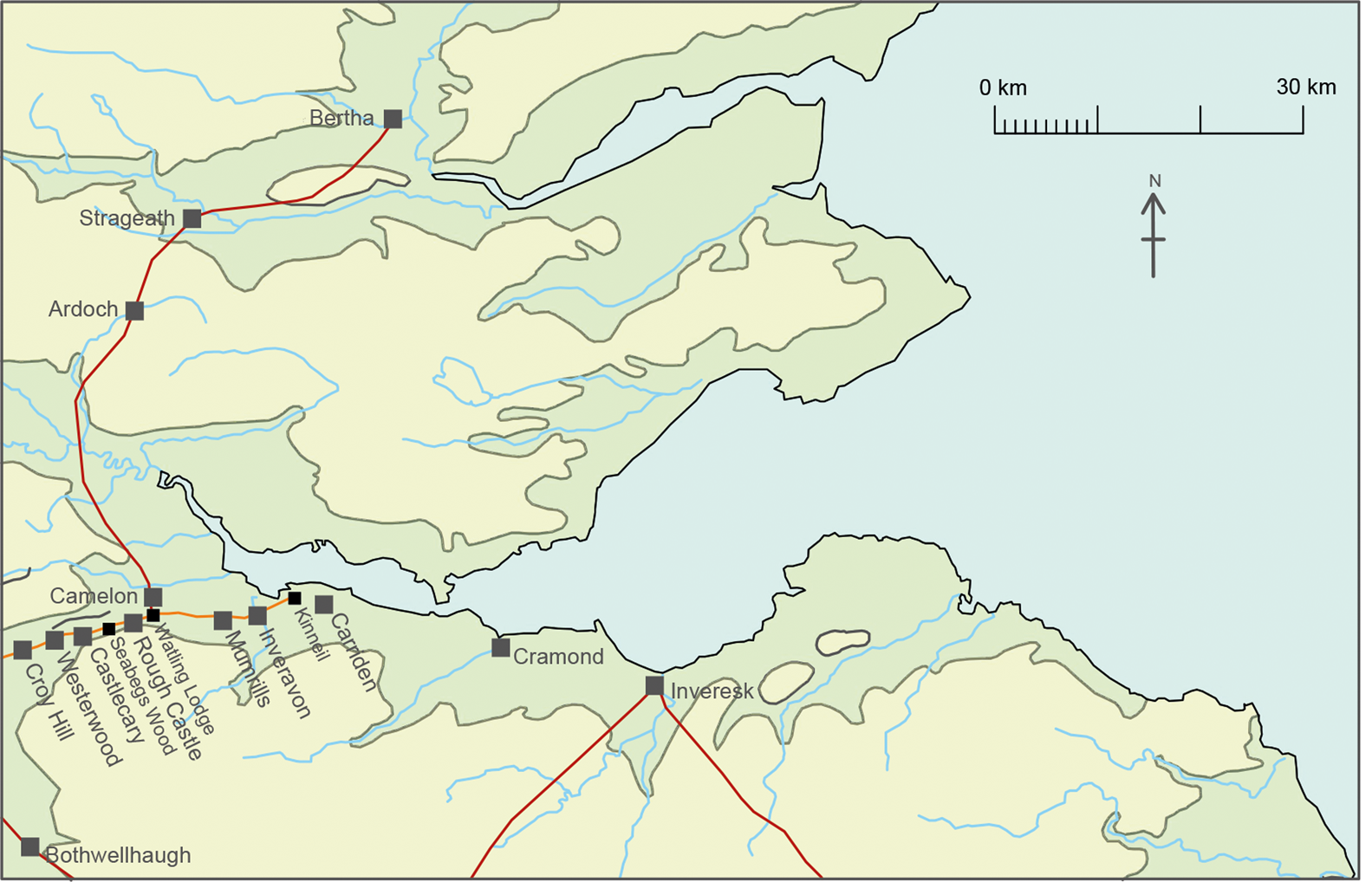

FIG. 4. Stages 2–4 of Hadrian's Wall (source: author).

FIG. 5. The two periods of the fort at Burgh-by-Sands II as described in the Supplementary Material.

FIG. 6. The Vallum looking eastwards from the Roman quarry at Shield-on-the-Wall. Hadrian's Wall underlies the road on the left of the photo (source: author).

FIG. 7. The stone fort at Castlesteads and its relationship to the Vallum as described in the Supplementary Material.

The Stanegate now crossed the Irthing and ran on its north side to the large fort at Carlisle, 13.3 km from Castlesteads. There might have been a fortlet at High Crosby, 7.3 km west of Castlesteads, or more probably a little to the west at Low Crosby, but there is only a slight hint of its existence. In terms of communications from the south, Carlisle was the most important hub on the Wall: roads from the Cumbrian coast, Chester and north-west England, and north-east England via Stainmore all met there. In the hinterland of Carlisle were forts at Old Carlisle and Wreay, possibly occupied in the early Hadrianic period, though there is nothing to show when they were established. There was also a road from Carlisle to Kirkbride, some 17 km distant, which in effect was a western extension of the Stanegate; its eastern section ran up to 2.5 km to the south of the Wall which west of MC 76 veered away to the north-west. One length has been seen west of the River Caldew.Footnote 39 Another possible sighting of this road was at Fingland Rigg, 5 km east of Kirkbride, where it seemed to be associated with a running ditch and fence lines of the supposed defensive system of the Western Stanegate.Footnote 40 The scanty remains of metalling are c. 150 m north of the likely course of the road as outlined by Bellhouse, which is followed more or less by the line of the modern B5307.Footnote 41

The next fort to the west of Carlisle, at a distance of 7.8 km, was Burgh-by-Sands I, which was 8.5 km from Kirkbride. It had an area of 2.0 ha and was sited 1.6 km north of the road just described. None of the pottery from the fort is necessarily earlier than the Hadrianic period. It faces north, away from the Stanegate, and might well have been built to support the Wall in the original scheme. Stratified pottery indicates that the fort at Bowness-on-Solway belonged to Stage 3. Its site overlooked the westernmost of the fords across the Solway in frequent use during medieval and later times.Footnote 42 If the ford existed in Roman times, as seems probable, MC 80 must have controlled it until replaced by the fort.Footnote 43 The westernmost fort supporting the Trajanic frontier was at Kirkbride, which was sited on the south side of the Wampool about 3 km from the point where the river flows into Moricambe Bay. The fort was of a large size, with an area of at least 2.0 ha and perhaps as much as 2.9 ha. Pottery from the site includes some BB1 of second-century date. Short lengths of a road between Kirkbride and Drumburgh have been seen just beyond these two fort sites.Footnote 44 The road covered the shortest distance (4.5 km) from Kirkbride to the Wall, and perhaps ended at MC 76 which lay only some 120 m east of the fort, which was an addition to the Turf Wall. The site must have been of importance from the earliest stage in the Roman occupation. The Solway was fordable at this point during medieval times by means of the Sandywath, and there is some evidence that the bay at Drumburgh was a Roman landing place.Footnote 45

How the Cumbrian coastal system of towers and milefortlets fitted into the building programme for the Wall is uncertain. One possibility proposed by Ian Caruana is that the system was established in two stages with the installations on the Cardurnock peninsula preceding the remainder.Footnote 46 This suggestion arose from the exceptional size of MF 5 (Cardurnock) which at 0.27 ha was almost as large as Haltwhistle Burn (0.3 ha). It was later reduced to the same size as MF 9 on the opposite side of Moricambe, which would be consistent with its conversion from the terminal installation of the first system into a regular milefortlet of the much more extensive series. MF 5 would have been an isolated terminus for the frontier works, some 6 km to the west of Kirkbride.

THE ADDITION OF PROJECTING FORTS: STAGE 2

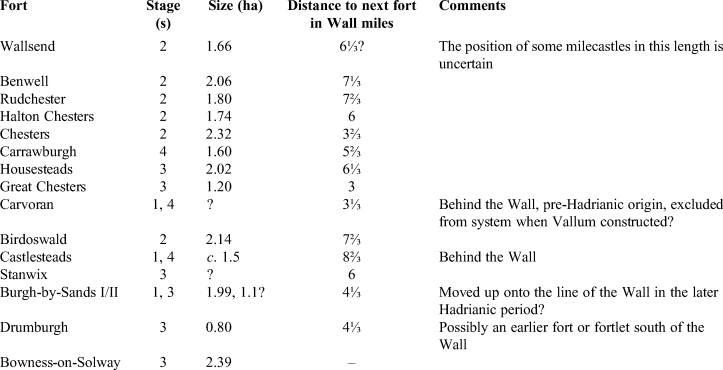

Five projecting forts were built in stone across the line of the Wall at its eastern end, requiring the demolition of some of its fabric (fig. 4, STAGE 2). The easternmost fort was at Wallsend, at the end of an extension of the Wall from Newcastle and at a point which commanded the junction of the Long and Bill Reaches, straight lengths of the Tyne; the westernmost was at Chesters, controlling the North Tyne valley. The other critical point was where Dere Street passed through the Wall at Portgate, which was controlled by the Wall gate and, 250 m to its east, by MC 22; both were supported by the projecting fort at Halton Chesters, 0.9 km east of Portgate. Pons Aelius and the original end of the Wall would already have been controlled by the suggested fort at Gateshead. Benwell and Rudchester were sited at convenient points between Wallsend and Halton Chesters. The five forts were spaced between 6 and 7⅔ Wall miles apart. A sixth projecting fort was built at Birdoswald, on the site of T49a TW, but the existence of a seventh at Burgh-by-Sands II can be dismissed, as is explained in Supplementary Material FIG. 5. In size these forts ranged between 1.66 ha at Wallsend, which was built for a cohors quingenaria equitata,Footnote 47 and 2.32 ha at Chesters, which accommodated an ala (RIB 3298) (table 2).

Table 2 the spacing of forts on or close to the line of the wall, and the order of their construction or rebuilding (stage 1: pre-existing or part of the original plan; stage 2: the projecting forts; stage 3: a.d. 128–131/33; stage 4: a.d. 131/33 and later)

There are building inscriptions dating to the governorship of A. Platorius Nepos (a.d. 122–125/7) at Benwell (RIB 1340) and Halton Chesters (RIB 1427), and the other forts in the series were presumably of this period. Various reasons are advanced below for regarding the other forts on the line of the Wall as later additions. The great augmentation of the forces on the eastern part of the Wall and the extension to Wallsend can only mean that the original system of control in the east was abandoned entirely. Low Learchild, Wooperton and a fort that perhaps lay at the northern end of the Devil's Causeway at Tweedmouth were presumably given up, together with Risingham, if it had been retained as part of the original scheme for the Wall. The addition of two new forts at Benwell and Wallsend might explain why Washingwells was not completed. It was large enough to have accommodated an ala, and the unit it was intended for could instead have gone to Benwell, known to have been held by a unit of this type in the later second century if not before (RIB 1329). Other units could have been moved north following the abandonment of hinterland forts such as Ebchester.

THE WESTERN OUTPOST FORTS AND THE CUMBRIAN COASTAL SYSTEM: STAGE 2?

Three forts were sited 10–12 km north of the Wall (fig. 4, STAGE 2). Bewcastle, connected by a road to the projecting fort at Birdoswald, was set among the fells and was not on a major route. Netherby, due north of Carlisle, was well placed to control the southern parts of Eskdale and Liddesdale. Birrens was separated from the Wall by the Solway; it had been preceded by a small Flavian post and was on what had been a major road leading to the centre of southern Scotland before the Trajanic withdrawal. Bewcastle, with an area of 2.4 ha, was more extensive than any of the forts on the Wall apart from Stanwix; later in its history, and perhaps originally, the fort might have accommodated a cohors milliaria equitata.Footnote 48 Netherby, held in 213 also by a cohors milliaria equitata (RIB 976–7), could have been of comparable size; Birrens was originally smaller, though its area was enlarged from 1.68 ha to 1.97 ha in the early Antonine period.

There were large forces at two of these forts. Clearly an important part of the Wall system in the west, Bewcastle and probably Netherby were comparable in size to the outpost forts beyond the Antonine Wall. All three forts have Hadrianic building inscriptions, which are known only from transcriptions made by antiquaries. The Bewcastle example (RIB 995) possibly included the name of Platorius Nepos, but this is far from certain.Footnote 49 The inscriptions from Netherby (RIB 974) and Birrens (not in RIB)Footnote 50 omitted ‘p(ater) p(atriae)’ from Hadrian's titles, and therefore are probably earlier than 128. The road from Bewcastle is aligned on Birdoswald where there is a projecting fort, but that does not exclude the possibility that Bewcastle was part of the original scheme for the Wall, together with Netherby and Birrens. There was perhaps an earlier track originally running north from one of the milecastles near Birdoswald, which was not replaced by a road until the fort was built.Footnote 51 Nevertheless, it seems more likely that these outpost forts belong to Stage 2. The apparent unrest or conflicts that led to a withdrawal from the area north-east of the Wall might have called for a different response in the west; instead of strengthening the Wall by the addition of a series of projecting forts, the emphasis was on controlling the main routes through the dales north of the Wall, with only one new fort on its line, at Birdoswald.

The Cumbrian coastal system of milefortlets and towers south of Moricambe might well have been built at this stage, together with the fort at Beckfoot, but they might equally belong to Stage 3.

THE LATER SERIES OF FORTS: STAGE 3

Since the 1950s a distinction has been made between primary forts on the line of the Wall, which seemed to be the majority, and those that followed later.Footnote 52 The primary forts were supposed to have included not only those that projected but also some with conventional plans. At first it was thought that the difference in the plans was because the projecting forts were solely for cavalry, their three gates beyond the Wall allowing their rapid deployment.Footnote 53 Later, after it was realised that the projecting forts probably accommodated units of various types, their plans were regarded as an ideal for which a conventional plan had to be substituted when topography prevented projections beyond the Wall.Footnote 54 Paul Austen, however, demonstrated that the only forts where this was the case were Housesteads and perhaps Bowness-on-Solway.Footnote 55 It is worth repeating that forts had priority over the building of the curtain; Balmuildy on the Antonine Wall is an example of a fort that preceded the fortlets. Housesteads, Great Chesters and Bowness-on-Solway were later than the projecting forts, as will be seen. They belong to Stage 3; had they been envisaged previously, they would have been built without delay at the same time as the projecting forts. Swinbank and Spaul in their study of the spacing of all the forts on the Wall, published 70 years ago, were not analysing what was for the most part a single plan, as they thought, but an arrangement that had developed in separate stages.Footnote 56 Some modifications of their views, not always widely accepted, have been proposed in recent years, and the spacing of forts on the Wall can now be seen to have resulted from responses to changing problems of security on the northern frontier.Footnote 57

During Stage 2, occupation would have continued in the forts on the Stanegate at Corbridge, Vindolanda, Carvoran and Carlisle, and also, it is assumed, at the forts built as part of the original scheme for the Wall at Castlesteads and Burgh-by-Sands I (fig. 4, STAGE 3). In other words, the Wall functioned as originally intended, except in the eastern sector and at Birdoswald. In the previously accepted scheme, there were supposedly six primary forts which did not project.Footnote 58 Castlesteads has already been discussed, which leaves Housesteads, Great Chesters, Stanwix, Burgh-by-Sands II and Bowness-on-Solway to be considered.

Housesteads is the only one of these forts to have been extensively excavated. Before it was built, there seems to have been settled occupation associated with the underlying T 35b, including a probable amphora burial. The excavations reported on by Alan RushworthFootnote 59 produced a maximum of 2,964 samian vessels; Hadrianic samian was remarkably scarce compared to the amounts from the projecting forts at Wallsend, Halton Chesters and Birdoswald, and from the outpost fort at Bewcastle. It is also possible that construction of the earth bank behind the fort wall had not been completed by the end of the Hadrianic period. These factors strongly suggest that Housesteads was built later than the projecting forts, allowing fewer years for samian to reach the site before the early Antonine advance into Scotland. There is of course no reason to think that Housesteads was not built until the return from Scotland. Setting aside other considerations, the construction date of the fort is established by a fragmentary building inscription which has been described as ‘acceptably Hadrianic’ (RIB 3325). It cites a cohort, the name of which is missing; the following line begins with the letters MI[…], plausibly expanded as mi[ll(iaria)] …, ‘a thousand strong’. Cohors I Tungrorum milliaria is known to have been at Housesteads later in the second century, and this inscription makes it likely that it was not only the first unit at the fort but was also responsible for building at least part of it.Footnote 60

At Great Chesters, a small fort with an area of 1.2 ha, there is a building inscription, found near the east gate, in which Hadrian bears the title ‘pater patriae’, granted in a.d. 128 (RIB 1736).Footnote 61 It is 6⅓ Wall miles west of Housesteads, and, as is explained the next section, both forts because of their relationship to the Vallum are likely to be earlier than c. a.d. 131–33. The relative scarcity of Hadrianic samian at Housesteads would be consistent with a date after a.d. 128, and the two forts could have been built at the same time.

Knowledge of the early histories of the Wall forts to the west of Birdoswald is thin. There was a Hadrianic fort at Stanwix, assumed to have been of turf and timber and built against the back of the Turf Wall. Rebuilt in stone after c. a.d. 160, it projected c. 20–25 m beyond the line of the Wall, unless the latter was realigned to meet the corners of the new fort, as at Birdoswald and eventually at Burgh-by-Sands II.Footnote 62 From the fort and a site to the west there are small assemblages with enough Trajanic and Hadrianic samian to allow the possibility that the turf and timber fort was added early in the building programme. There are complications, however, for the fort is on the predicted site of T 65b and just to the west there must have been a gate to take the road to Netherby and Birrens through the Wall. Some of the early pottery might have been derived from activities preceding the fort, perhaps especially with trading activities associated with the Wall gate. The large amounts of samian ware from the fort at Carlisle are more informative. Following a peak in the earlier Hadrianic period, quantities of the ware decline markedly, which would be consistent with the replacement of Carlisle by Stanwix as the most important fort in the western part of the Wall in the later Hadrianic period.

How long Burgh-by-Sands I remained in occupation until it was replaced by a new fort on the line of the Wall remains uncertain. There is some Hadrianic pottery from an extra-mural site south of the later fort, but it could represent a brief period of occupation in the a.d. 130s. Unpublished excavations reviewed in the Supplementary Material point to the existence of a small fort of c. 1.1 ha, of turf and timber and abutting the Turf Wall, which was later extended to the north and rebuilt in stone, a sequence paralleled at Stanwix (fig. 5).

At Drumburgh, an addition to the Turf Wall, there is nothing to indicate the date of the turf fort more precisely; it was possibly held by part of the same unit which occupied the small fort at Burgh-by-Sands II, foreshadowing arrangements common at the forts on the Antonine Wall. A later Hadrianic terminus post quem for the fort at Bowness-on-Solway is established by a large group of pottery, possibly a foundation deposit, from a pit under one of the original barracks.

There are finds or structural relationships which demonstrate that Housesteads, Great Chesters and Bowness-on-Solway cannot be as early as Stage 2 when projecting forts were added to the Wall, and it is likely that Stanwix, Burgh-by-Sands II and Drumburgh are also of later Hadrianic date. All were added to the Wall probably as part of the same programme – Stage 3 – which extended the arrangements of Stage 2 in the eastern sector to the entire length of the Wall, reverting to traditional fort planning. The relationship of Great Chesters to the Vallum provides a terminus post quem of a.d. 128 for this programme.

THE VALLUM

The Vallum consisted of a steep-sided ditch with a flat base, which was flanked by two revetted mounds.Footnote 63 It was a formidable obstacle which has come to be seen by some as defensive, even though there were apparently no towers or installations on its line to keep it under direct surveillance (fig. 6).Footnote 64 As far as its position in the sequence of Wall building is concerned, a long-established principle is that this continuous earthwork could not have preceded the addition of forts to the Wall, because, in Richmond's words, in the original scheme it ‘would have cut off the fighting garrison [on the Stanegate] from its field of operations’.Footnote 65 The possibility that the forts added to the Wall were intended from the very beginning, their sites to be determined later, has already been rejected, and thus the Vallum cannot have been planned or carried into effect as part of the original scheme. This is confirmed by a spatial relationship common to all the forts where causeways across the Vallum to their south are known. The causeways are exactly opposite one of the fort gates, that is, they are on the same lines as one of the major roads in these forts: the via decumana in the projecting forts at Benwell and Birdoswald and the via principalis in the later forts at Housesteads and Great Chesters. The causeways at Benwell and Birdoswald had gateways that took the form of monumental arches, known at Benwell to have been fitted with gate leaves. Their character and precise alignment with the fort gates, also architecturally elaborate,Footnote 66 suggest that together they were planned to form ceremonial axes, dignifying the approaches from the south to the most important installations on the Wall. At the other two forts, argued here to have been later than the projecting forts, there were apparently no arches on the Vallum causeways. In terms of architectural planning, the Vallum cannot have preceded the forts, for that would have rendered its monumental arches meaningless, though the Vallum could of course have been later than the forts.

The most considerable attempt to show that the Vallum was part of the original scheme nevertheless cannot be ignored, partly because it raises another matter. An analytical survey by Humphrey Welfare at Shield-on-the-Wall, between T 32b and MC 33, found that the Vallum had crossed a sandstone knoll and had ended to the east of a quarry.Footnote 67 Immediately south of the quarry, and respecting the line of the Vallum, was a camp with an area of c. 1.4 ha, evidently to accommodate a unit building the Wall. Because these three elements respected each others’ positions, the quarry, camp and the eastern part of the Vallum (which was continued across the floor of the quarry when it passed out of use) were judged to have been contemporaneous. That meant the Vallum had been constructed at the same time as the Wall, its stone being supplied from the quarry. Welfare's interpretation of the survey results does not take account of the two stages in the construction of the curtain, which in this sector were probably separated by some years.Footnote 68 Although the curtain is concealed under the Military Road, the Broad Wall foundation has been seen to the west where it extended beyond the wing walls of T 33b,Footnote 69 and nowhere to the east, as far as Newcastle, is it known to be absent. The digging of the Wall ditch where it cut through sandstone would have produced enough material to form the foundation.Footnote 70 The profile of the Wall ditch is very sharp at Shield-on-the-Wall, a sure indication that most of its depth was cut through stone. It is doubtful whether a separate quarry would have been required at Shield-on-the Wall for the first stage of building, and the camp, quarry and Vallum probably belong to the second, Narrow Wall stage.

An idea now current is that the Vallum was built piecemeal and that its line was surveyed from the forts.Footnote 71 If the forts were added in separate phases, where would the ends of the earlier sections of the Vallum have been in Stage 2? It might be argued that the quarry at Shield-on-the-Wall was exploiting stone immediately west of the point where an early length of the Vallum had originally ended. In Stage 2 the Vallum would thus have extended six Wall miles west of Chesters, cutting off access from forts on the Stanegate to the turrets and milecastles in this length, which seems unlikely. The only other terminus known at presentFootnote 72 is above Harrow's Scar at Birdoswald, where excavations uncovered the point at which the Vallum ditch ended, which was 4.5 m to the west of MC 49 and 400 m east of the fort.Footnote 73 The milecastle was effectively excluded from the zone between the Vallum and the Wall, a unique occurrence best explained by the precipitous slope to the south which left a space only 11 m in width between the Turf Wall and Vallum ditch: a gap was needed for access to the area north of the Vallum.

If in Stage 2 only parts of the Wall were isolated from the south by the Vallum, the movements it was intended to prevent would be channelled towards other areas of the Wall, particularly the central sector, which at this early stage were held in less strength than elsewhere. It is far more likely that the Vallum was built in a single operation as part of Stage 3 when forts had been placed on the line of the Wall throughout its entire length. The building inscription (RIB 1736) from Great Chesters provides a terminus post quem of a.d. 128 for the Vallum, and it had been completed by a.d. 131–33 (RIB 1550) when the fort at Carrawburgh was built across its line. Its obliteration at this point cannot be taken to indicate that the earthwork as a whole was redundant only a few years after it was formed. Haverfield found that on the east side of Carrawburgh the outer fort ditch opened into the south side of the Vallum ditch.Footnote 74 The line of the Vallum ditch, though presumably not its flanking mounds, seems effectively to have been continued around the southern perimeter of the fort by its outer ditch. This was perhaps not an entirely novel arrangement: according to Haverfield, the Vallum ditch at Chesters was continuous with the southern ditch of the pre-existing fort, here regarded as of Stage 2, and it is possible that there was the same relationship between the equivalent ditches at Burgh-by-Sands II (fig. 5).Footnote 75

Finally, when Castlesteads was rebuilt in stone later in the Hadrianic period, possibly in a.d. 136–38 (see below), the Vallum crossing was aligned on the south-east gate and the axis of one of the principal streets of the new fort (fig. 7), evidence that the earthwork was maintained and where necessary modified until at least the last years of Hadrian's reign.

CARRAWBURGH AND SUBSEQUENT REBUILDINGS OF FORTS: STAGE 4

The fort at Carrawburgh, which as noted above extended across the Vallum, has always been regarded as a later Hadrianic fort (fig. 4, STAGE 4). A building inscription of cohors I Aquitanorum can be restored to include the name of Julius Severus, governor in c. a.d. 131–33 (RIB 1550).Footnote 76 It provides a terminus ante quem for the construction of the Vallum. Another inscription, almost certainly Hadrianic, mentions cohors I Tungrorum (RIB 3317), probably at Housesteads in this period and too large a unit to have been stationed at Carrawburgh. The Tungrians might have been responsible for building parts of the fort, with cohors I Aquitanorum continuing the work when it arrived. Another local instance of a non-legionary unit building away from its base was the vexillation of the classis Britannica which built the granaries at Benwell under A. Platorius Nepos (RIB 1340). It is possible that this detachment of the fleet had its main base at South Shields while work on the Wall was in progress.

The fort at Carvoran was rebuilt in stone and probably to a different plan in a.d. 136–38 (|RIB 1778, 1818, 1820). The rebuilding at Castlesteads, also to a different plan, would be of the same period if the name of a governor, Ti. Claudius Quartinus, has been correctly restored on a building inscription (RIB 1997–8 + add.).Footnote 77 Perhaps the renovation of these two forts was part of a wider programme that included the rebuilding of the eastern part of the Turf Wall in stone. Carrawburgh could be regarded as the result of a separate and earlier initiative, but equally could have marked the beginning of minor improvements and essential renovations, once the new forts were built in Stage 3.

FORTS, NATIVE POPULATIONS AND THE HADRIANIC FRONTIER WORKS

The Trajanic frontier, running from the mouth of the Tweed in the north-east to Kirkbride in the west, was 166 km in length. It consisted essentially of a series of forts, for the most part irregularly spaced and only reinforced systematically by towers and fortlets over a distance of 20 km between Pike Hill west of Nether Denton, where the Wall incorporated an earlier tower, and Barcombe Hill, just to the east of Vindolanda, where the easternmost tower was sited. Only one other fortlet, at Longshaws on the Devil's Causeway, which might have been part of the Trajanic frontier system has been identified with any certainty. Different problems in various parts of the frontier would explain the uneven distribution of forces along its length. On the coastal plain of Northumberland, and perhaps in North Tynedale and Redesdale, there were fewer forts because the native populations were compliant. The concentration of forces from Vindolanda westwards presumably indicates that this was the area most at risk of incursions. Forts were spaced at more frequent intervals along the westernmost 40 km of the frontier, but there were no fortlets and probably no towers associated with them.Footnote 78 It seems this area was more secure than that immediately to the east.

For the most part, Stage 1, the original scheme for the Wall, preserved the Trajanic distribution of forces, though some forts were rebuilt or moved to more advantageous sites (table 3). The Wall with its uniform succession of milecastles and pairs of turrets made almost no distinctions between areas of greater or lesser security. It can be seen as a strategic element in the system of frontier control. Forces behind and beyond the Wall could be concentrated for the long term in areas where the threats were most apparent. The Wall itself secured the entire Tyne–Solway isthmus, and could have been reinforced as necessary at any point, serving in an emergency as a backstop and a starting point for counterattacks. Once building of the Wall began, however, the needs of local security again became apparent. Construction to the west of the River Irthing was in turf rather than stone, except for the turrets, so that the work could be completed more quickly.Footnote 79

Table 3 the four stages in the development of hadrian's wall before the advance into scotland in the early antonine period

Priority was also given to the sector of the Wall between Newcastle and the North Tyne, which is where five of the six projecting forts were added in Stage 2, the first revision of the scheme. Wallsend was at the end of the Narrow Wall extension from Newcastle, and Birdoswald, the sixth projecting fort, was added at the eastern end of the completed Turf Wall, superseding or supplementing Nether Denton which was isolated from the Wall by the Irthing. Continuation of the Trajanic arrangements on the Northumberland coastal plain had been short-lived, and the eastern sector of the Wall was greatly strengthened by the projecting forts. They were a remarkable innovation, but what were they meant to achieve? Three main gates opening north of the Wall certainly permitted the rapid deployment of a unit from its fort.Footnote 80 This facility has long been regarded as of prime importance, for, as Eric Birley wrote, ‘in a sense, we may put it that the stationing of units of the field army in forts on its [the Wall's] line was merely coincidental, to give them a convenient springboard and a useful lateral line of communication’.Footnote 81 These units, according to Birley, were not drawn on to man the milecastles and turrets, which were entrusted to irregular units. This now seems doubtful,Footnote 82 but the idea of the forts as essentially bases for campaigning and aggressive patrolling beyond the Wall is still influential. If that were so, why were the forts not placed wholly north of the Wall?Footnote 83 The western outpost forts were obviously regarded as secure bases for large and versatile units, even though they were sited 10–12 km beyond the Wall, with Birrens separated from it by the Solway. On the Antonine Wall, Camelon, with an area of 2.9 ha, was sited 1 km north of a gate through the Wall at Watling Lodge. Forts in these forward areas were independent of their Walls for protection. Those on the line of Hadrian's Wall ignored positions a little to its north which would have offered better lines of sight, as for example at Benwell, Rudchester and Haltonchesters. Their physical integration with the Wall augmented their defences, preventing them from being outflanked. At the same time, they supported their adjacent minor installations and lengths of curtain; even Birley, describing the presence of units on the line of the Wall as in a sense ‘coincidental’, accepted that the ‘fort-commanders normally had groups of milecastles and turrets under command’.Footnote 84 The placing of forts on the line of the Wall expressed the indispensable part they played in its protection. That is not to deny their use as bases for activities to the north, but rather to question the previous emphasis on this aspect by Birley and others. The building of later forts that did not project beyond the Wall and with only one gate opening to the north, an arrangement that was standard on the Antonine Wall, seems to be a better representation of their purpose than the three northern gates of the earlier projecting forts.

The western outpost forts, assuming that they were added in Stage 2, would seem to have been a response to a problem in south-west Scotland not evident in the Trajanic arrangements. It was probably at the same time that the system of milefortlets and towers was extended along the Cumbrian coast to the south of Moricambe. Failure of the arrangements in the territory north-east of the Wall also brought about the addition of the five projecting forts in the east. All these changes could have been the result either of warfare in c. a.d. 124–25, perhaps sufficiently widespread to have affected the entire province, or of worsening relationships with parts of the native population that preceded the war.Footnote 85

Stage 3, which took place at some date between c. a.d. 128 and 131/2–133/4, saw the addition of forts to the entire line of the Wall, while, to the west of Newcastle, the Vallum sealed off a zone behind the Wall. There were presumably problems to the south which were countered by improvements to the whole Wall system on a scale comparable to the works in Stages 1 and 2. Nothing else indicates warfare at this time, but perhaps the building programme was precautionary and succeeded in removing the threat. In at least part of the central sector, completion of the Wall curtain could not have taken place before a.d. 128, the earliest date possible for the building of Great Chesters where the fort and Narrow Wall were built at the same time; the completed curtain at Housesteads was later than the fort. There are other signs of a long delay before the curtain was completed in the central sector: peat and silt had accumulated at Peel Gap between the Broad and Narrow Wall phases, and the line of the curtain at Highshield Crag and at Great Chesters ignored the Broad Wall foundation which weathering and plant growth had perhaps rendered useless.Footnote 86 Earlier neglect of this sector suggests that the main threats to the security of the frontier were at first in the eastern and western sectors of the Wall.

The only subsequent additions were the forts at Carrawburgh, built in c. a.d. 131/2–133/4, and perhaps at Moresby on the Cumbrian coast, which was no earlier than a.d. 128 (RIB 801). Subsequent activities were confined to the rebuilding of earlier structures in stone. Work at Carvoran is dated by inscriptions to a.d. 136–8, and Castlesteads was probably rebuilt during those years. Rebuilding in stone of the eastern part of the Turf Wall also began towards the end of the Hadrianic period. These disparate activities can be seen as the fourth stage in the development of the Wall: after the transformations of the whole system in the previous two stages, the works in Stage 4 translated what had already been established into more permanent forms.

CONCLUSIONS

The first stage of the Wall was the consolidation on a grand scale of the frontier which Hadrian had inherited from Trajan. The later stages were pragmatic modifications of the original vision, almost certainly driven by shifting focuses of resistance amongst the peoples of northern Britain beyond and behind the Wall. The addition of forts to the line of the Wall took place mainly in Stages 2 and 3 as a result of separate decisions. Stage 3 was not envisaged when Stage 2 was carried out because otherwise, fort-building being a priority once decided upon, all the forts would have been built as part of the same programme. Nothing suggests that the existence of the Vallum was anticipated until work began on it in Stage 3. The fourth stage, apart from the addition of the fort at Carrawburgh, was a new episode of consolidation with two forts and part of the Turf Wall being rebuilt in stone.

This paper has been concerned above all with setting out the structural sequences and relating them to dated building inscriptions and the less specific evidence of pottery. It can only take an agnostic stance on historical problems, in particular whether Hadrian ordered the building of the Wall when he visited Britain in a.d. 122, which is the traditional view, or had inspected work already in hand, perhaps conceiving the idea of projecting forts on the Wall.Footnote 87 What this paper can contribute to the wider understanding of this Hadrianic project is an appreciation of the ways in which the original vision was altered by a series of decisions springing from political and geographical realities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I am very grateful to Nick Hodgson and Matt Symonds who commented in penetrating detail on many aspects of this paper, much to its benefit. Thanks also to those acknowledged in the Supplementary Material who made unpublished reports available.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

For supplementary material for this article, please visit <https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X2200023X>.

The supplementary material lists the forts and fortlets (excluding those on the Antonine Wall) discussed in the main text together with information, published or in the grey literature, which amplifies their relevant structural histories and dating, in some instances with further discussion.