INTRODUCTION

Colchester's North Cemetery, as defined by M.R. Hull,Footnote 1 lies beyond the river Colne and was first noted by the local antiquarian William Wire in 1842. Burials were found east of Colchester's North Station during the construction of the railway, with a thin scatter between there and the river, but there was a concentration at the brickworks that lay to both the immediate north and south of the railway.Footnote 2 All these burials were probably of people living in the as yet poorly defined suburb north of the river.Footnote 3

THE BRICKYARD FINDS

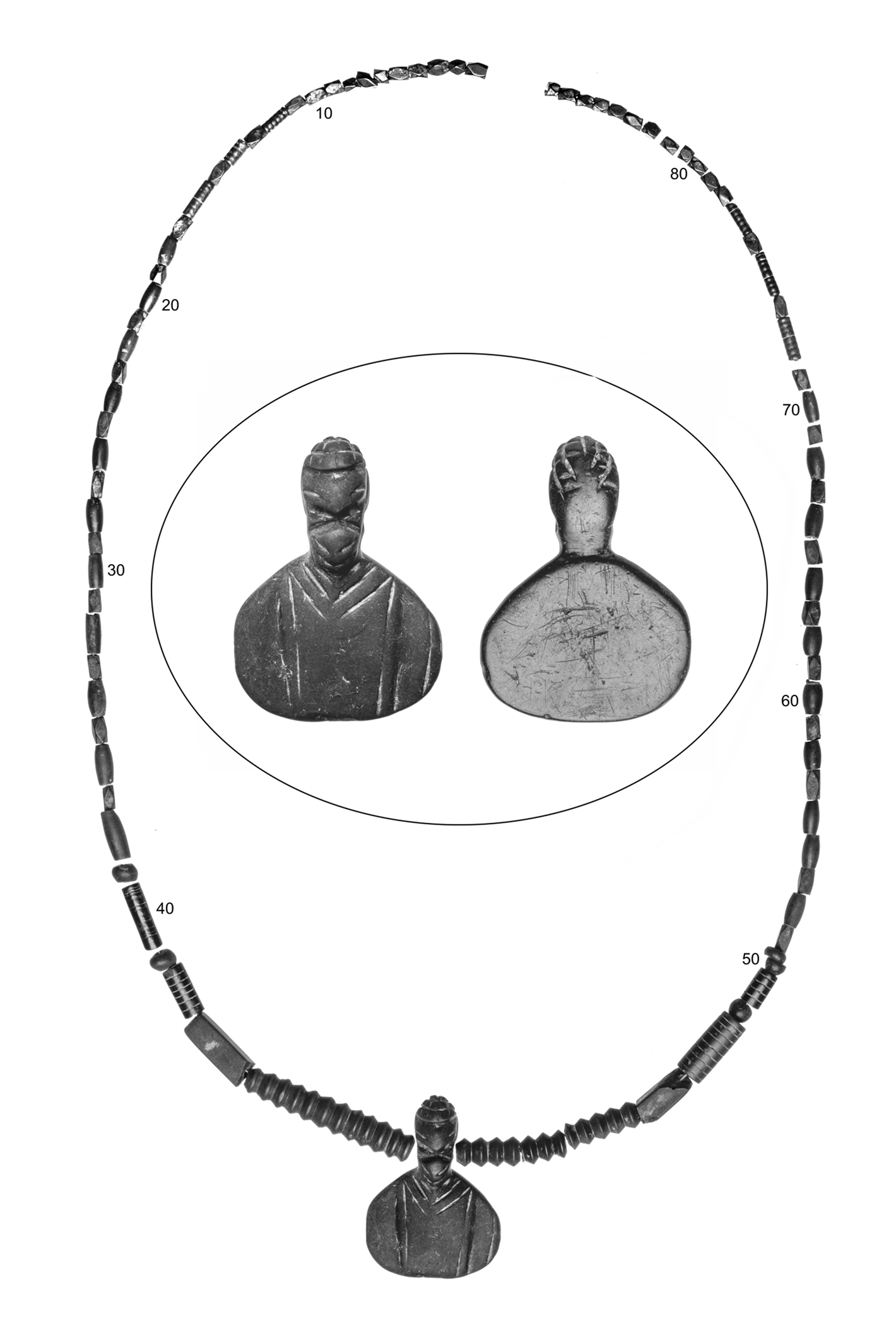

In 1912 Henry Money, the former owner of the brickyard near the railway, sold several Roman finds to the Colchester and Essex Museum.Footnote 4 By tracking his career (see online appendix 1), the date of their recovery can be narrowed down to between c. 1892 and 1910, probably towards the middle of that range. Some of the items he sold to the museum are mentioned by Hull in his description of the North Cemetery: ‘gold earrings, a silver spoon, and jet necklace with pendant, came to the Museum’. The full list is recorded in the museum's Annual Report for 1912.Footnote 5 It is summarised here with some comments and updated identifications: acc. no. 2499.12, shale armlet, diameter 73 mm; 2500.12, silver spoon with pear-shaped bowl, length 124 mm; 2501.12, bronze bracelet fragments (?burnt); 2502–3.12, fragments of two pale green glass unguentaria; 2504.12, a pair of gold-wire earrings with double-coiled terminals, diameter 14.5 mm (these are finger-rings of Guiraud's Type 6Footnote 6); 2505.12, a slightly tapering tubular jet bead with two fine incised grooves at one end and six at the other, length 35 mm, maximum diameter 11 mm; 2506.12, a carved jet pendant in the form of a bust with African features, height 36.5 mm, maximum width 27 mm (fig. 1); 2507.12, 93 jet beads of various forms and sizes, made into one string with the carved pendant bust (fig. 1); 2508.12, 91 beads of coloured glass of various forms and sizes, made into one string; 2509.12, 16 glass beads made ‘to imitate pale yellow amber’ (these are late post-medieval/early modern and only 15 now remain); 2510.12, seven small gold-in-glass beads, both double and single segments.

FIG. 1. The black mineral amulet and necklace from Colchester, with every tenth bead numbered (excluding the bust). Scales: amulet 1:1; necklace with amulet 2:3. (Photographs by R. Stroud; © Colchester Museums)

Many of these items suit a late Roman date, such as the spoon, jet beads and pendant bust; others were produced over long periods, such as the gold finger-rings and gold-in-glass beads, while the yellow beads (actually an opaque lemon yellow, very unlike amber) are post-medieval, probably Victorian, and were presumably included by Money in error.Footnote 7 No stratigraphic associations were recorded at the time by the curator, A.G. Wright, but the expression ‘made into one string’ implies that he doubted that the two long strings were faithful records of Roman necklaces. As the gold-in-glass beads (2510.12) had been separated out because of their distinctive colour, this doubt was clearly justified. The questions of how much jewellery was found from how many burials, and how closely associated the pendant bust was with any of the beads, must remain moot. It is certainly possible that the whole group came from the burial of a young female, but the shale armlet 2499.12 and the long jet cylinder bead/pendant 2505.12, for example, may be from a different grave, and two particularly long and deeply segmented cylinder beads on the necklace 2507.12 may belong with them. That 2505.12 had not been incorporated into the string of black mineral beads by Money adds credence to this suggestion, and, as a group, these two (or four) objects are reminiscent of the Joslin Collection grave group 87/14, which includes three long jet cylinder beads and a jet bracelet, as well as a jet bear, a large jet ring and a pottery beaker.Footnote 8

If all the objects acquired from Money were indeed from a single grave, they would form a similar group to one from a burial at the cemetery at Koninksem (Coninxheim), southwest of Tongeren, Belgium (containing a jet bust, jewellery and glass vessels).Footnote 9 Professionally excavated in September 1908, its contents are summarised in table 1 and those from the North Cemetery are matched against them.Footnote 10 Two other burials bear close comparison: (1) the richly furnished H.321 burial from Walmgate, York, with its jet jewellery, jet Medusa pendant, bead strings in a variety of materials,Footnote 11 glass unguent bottles and two coins,Footnote 12 and (2) the Chelmsford burial (originally thought to be a hoard) with jet jewellery, jet Medusa pendant and lion amulet, and a glass pipette bottle.Footnote 13

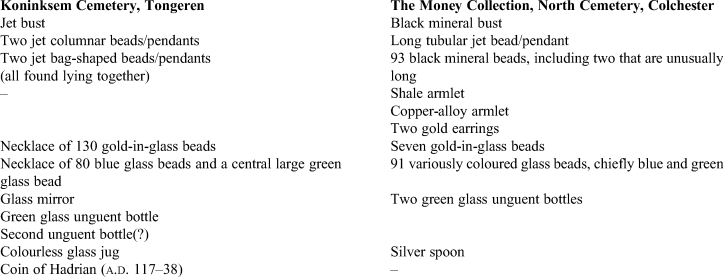

TABLE 1 THE KONINKSEM GRAVE GROUP AND HENRY MONEY'S NORTH CEMETERY COLLECTION

THE BLACK MINERAL JEWELLERY

The pendant is in the form of a human bust; it ends just above the waist, with the body flattened but the head fully three-dimensional: height 36.5 mm, maximum width 27 mm. It is pierced from side to side through the ears. Tight curly hair is shown by deep grooves running across the head from front to back and side to side. The face is grotesque, its features formed by grooves that are often wide and deep. It has slanting eyebrows and eyes set some distance apart. The nose is formed by four grooves set in a lozenge and almost as wide as both the curved mouth and the distance between the outer corners of the eyes. There is little or no neck. The shoulders are strongly sloping before dropping down to the arms, which are hinted at by a slight groove close to each side. Clothing is indicated by pairs of parallel grooves forming a garment neckline and running down from each shoulder; they may have been intended to represent stripes or bands in the fabric. Short, shallow scratches, presumably tool marks, are less noticeable on the front but prominent on the back. Some longer, wider and deeper grooves on the back were perhaps made when the pendant was dug out of the ground. The back is polished to a shine, while the front is worn, dull and slightly cracked in a few places. The item would originally have been polished, but much handling has worn away the shine. This use-wear points to the amulet being of some age when placed in the grave. It has not proved possible to identify the material of the pendant, but it is black and appears to be jet. Of the analysed Medusa and portrait pendants in the York Museum, one is of cannel coal and is dull both front and back, while three are of jet and dull at the front but polished at the back.Footnote 14

The black mineral beads are catalogued in online appendix 2 and summarised in table 2, where many are matched to a typology. They are numbered as strung, and as marked on fig. 1. Most are black, and the faceted cuboid beads and finely grooved cylinders are certainly made from jet. The surfaces of some of the other beads are quite dull and several have patches of brown, while the deeply segmented cylinders – nos 44 and 45 – that flank the pendant are dark brown/black. There is a possibility that these ‘brown-black’ beads are made from a different black mineral. The necklace is now composed of 88 beads, five fewer than when it was accessioned in 1912; this discrepancy might be accounted for in some part by counting the three broken parts of bead no. 45 as separate pieces and perhaps by some of the smaller beads breaking over the course of more than a century. Other than that, and the recent replacement of the metal wire on which it was strung, it remains as it was when it was acquired. The stringing is symmetrical, with faceted cuboid beads at the terminals and then alternating with long barrel-shaped beads, although there is a slight deviation in this arrangement between beads 54 and 57, where a faceted cuboid is missing. Oblate beads then act as spacers between grooved cylinders at each junction with the central section, which is composed entirely of long beads of various forms. One half of oblate bead 50 is missing, but has been replaced by the similarly sized discoid bead 51.

TABLE 2 THE BLACK MINERAL BEADS

It would be unwise to accept without question that this stringing represents a necklace as originally deposited in a burial, not least because there is no direct proof that the beads and pendant were even originally associated. Justification for association is provided by the jet necklaces incorporating Medusa and portrait pendants excavated under more controlled conditions,Footnote 15 while the possibility that the pendant was rather differently strung when it was excavated is provided by a Medusa pendant from London that was hung on a necklace of both jet and glass beads.Footnote 16 At the worst, as an antiquarian find not excavated under controlled archaeological conditions, the Colchester pendant may not even have been an undisturbed grave deposit. Only two of the six Medusa and portrait pendants from York are indisputably from grave groups, as are only eight of the 20 Medusa pendants listed by Hella Eckardt from Belgium, Britain, France and Germany; conversely, several are antiquarian finds lacking stratigraphic data and so these too may be from burials.Footnote 17

THE GLASS BEADS

The glass beads are catalogued in online appendix 2 and summarised in table 3; the gold-in-glass beads, now strung separately, were probably originally incorporated in either the long glass string or the black mineral string. Similar necklaces incorporating beads of various shapes and colours have been found in late Roman cemeteries at, for example, Colchester, London and Winchester, with blue and/or green often dominating, as here.Footnote 18 The stringing is not quite as regular as on the black mineral necklace, but again there is a central section containing larger and differently shaped beads. As Catherine Johns has remarked for other bead strings, it is likely that, after excavation, the beads were simply ‘restrung in a way that seemed feasible’.Footnote 19

TABLE 3 THE GLASS BEADS: THOSE IN THE MAIN GROUP ARE LISTED IN ORDER OF FIRST APPEARANCE

OTHER PENDANT BUSTS AND HEADS

The pendant can be grouped with a number of busts made from jet found in the western provinces, all undoubtedly amuletic and at least two from graves. Wilhelmine Hagen describes and illustrates five examples – three from Cologne in Germany, one probably from Cologne and one from Koninksem (Coninxheim) in Belgium (see table 1) – and she cites parallels in one Austrian and one Italian museum.Footnote 20 There is another jet bust from north-west Spain.Footnote 21

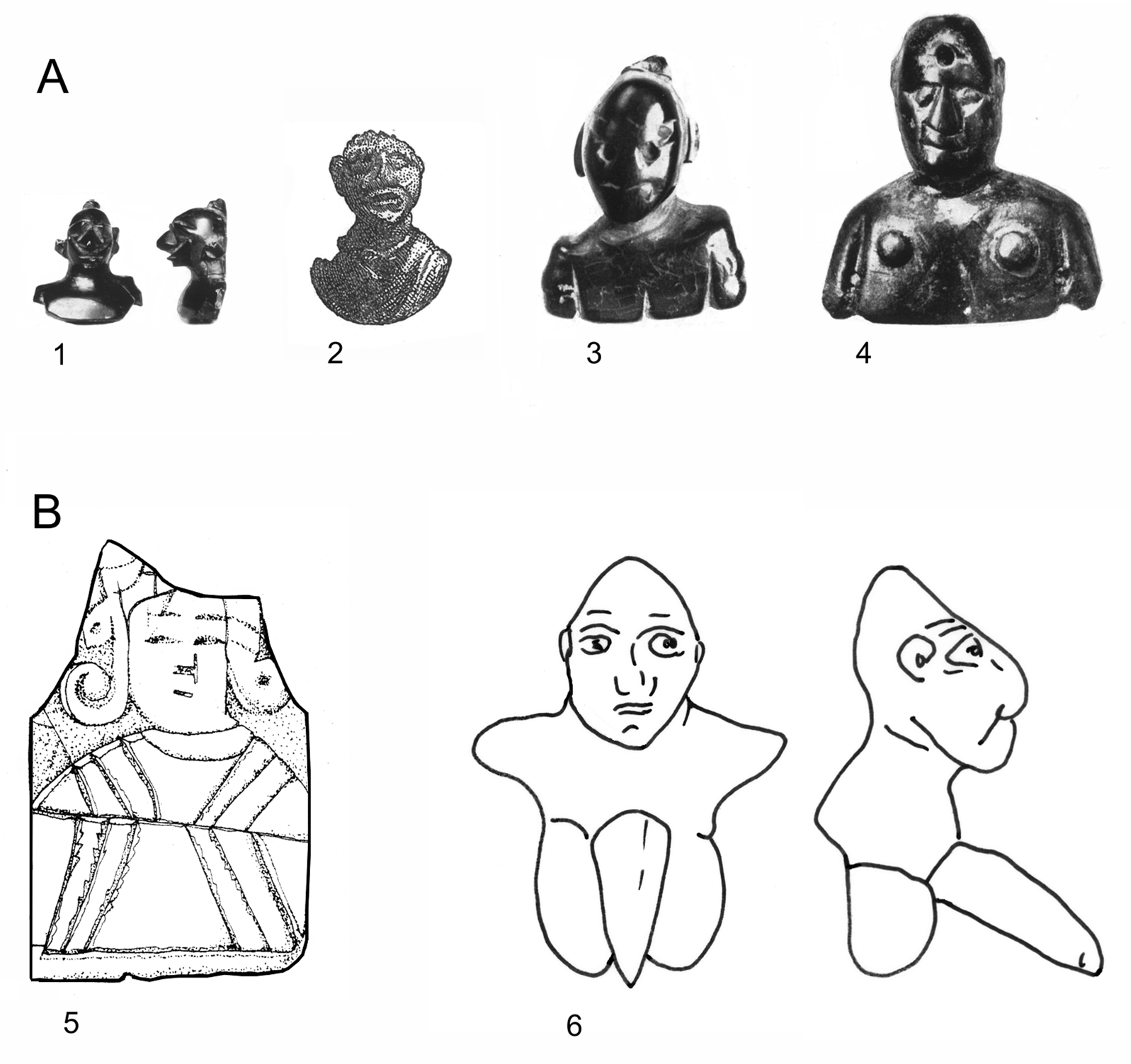

Only the German E7/1–2 and the bust from Spain are very similar; E7/1 is from Cologne, E7/2 may also be from Cologne, while the Spanish bust is from Astorga (Asturica Augusta), Léon. They range in size from 15 mm high (E7/1; fig. 2A, 1), to 19 mm (Astorga), to 25 mm (E7/2). On the two busts from Germany the head is pierced horizontally for suspension above the large ears, while the Astorga bust has a loose loop of thin gold wire about the neck and a length of more gold wire is attached to the loop. The three terminate at the upper chest and have a flat back. They show a male with a small topknot on an otherwise hairless head, prominent and exaggerated facial features (in particular a beak-like nose), fairly square shoulders and a naked chest with the arms marked by shallow notches in the jet. The Astorga bust is described as that of an African, but Hagen merely refers to the German pair as male busts and remarks that there was no attempt to make them realistic portraits.Footnote 22

FIG. 2. (A) Amulets referred to in the text: 1 E7/1, from Cologne; 2 E9, from Koninksem; 3 E8, from Cologne; 4 E10, from Cologne (after Hagen Reference Hagen1937) and (B) 5 The Chelmsford bone plaque; 6 the Boughton Aluph copper-alloy amulet (after Wickenden Reference Wickenden1992; Bradshaw Reference Bradshaw1980). Scale 1:1.

An amber bust with features similar to this group of jet pendants was found with other amulets in a late Roman child's grave in the Butt Road cemetery at Colchester. At 19 mm high it falls within the same size range as the jet examples, and has a topknot, large nose and large ears, but below the neck there is only a narrow, plinth-like section of the upper chest.Footnote 23 Martin Henig notes the topknot as his principal reason for identifying this pendant as the head of an African,Footnote 24 but there is no substantive evidence to support this conclusion (see below).

One of the other busts from Cologne (E8; 31 mm high) shares the topknot of the examples noted above, but the face is smooth and almost featureless, the shoulders are lopsided, the piercing runs vertically down the back of the head and the bust extends further down the chest with the arms clearly shown (fig. 2A, 3). It may be a poorly executed copy.

Bust E10 from Cologne is very distinctive, both less exaggerated and more strange (fig. 2A, 4). At 36 mm high, it is the closest in size to the Colchester pendant. Like E8, bust E10 extends well down the chest and the arms are defined by a long groove. The face is heavy and marred by the suspension hole running horizontally from the forehead to the back of the head. Even though the ears are exposed, Hagen suggests that the head was covered not by hair but by a helmet with cheek-pieces (Backenklappenhelm). She was no doubt led to this conclusion by the lack of a topknot, the prominent cheekbones and the vertical lines running from nose to chin, but, again, a mix of smooth and angular features, along with E10's beaky nose, reference the group discussed above. What really sets this piece apart are the large silvered nipples that seem to identify it as female. Hagen cites two parallels to E10: one in the Antikensammlung Wien (inv. X 150) and a smaller one in the Aquileia Museum.

The bust from Koninksem (E9; 23 mm high) differs again, being the most naturalistic and more akin to a portrait bust, with the lower end cut to a regular curve and the body draped; it is noted by the excavators to be well cut and of a lustrous black (fig. 2A, 2).Footnote 25 Pierced horizontally above the ears, it has a suggestion of hair and, considering the size of the pendant and the material, the features are not particularly exaggerated. Large ears give it a masculine appearance and, described as beardless, it was interpreted as male on excavation. Stylistically it resembles the draped images on portrait pendants, such as those from Cologne and York.Footnote 26 Could it have been cut down from one? Four other highly distinctive items came from the same burial (table 1): two large column-like jet beads and two bag- or vase-like jet pendant amulets.Footnote 27 The latter are similar to examples in amber from a necklace of pearls, bone beads and glass beads from a late Roman female grave at Dorchester and in black and yellow glass from a necklace of glass and amber beads in a late fourth-century child's grave at Butt Road, Colchester.Footnote 28 At 40 mm, the columnar beads are only 5 mm longer than the jet bead 2505.12 from the Money Collection. Beads of such size and solidity may be better defined as pendants, and both the Koninksem and Colchester pieces could have formed the central focal point of a necklaceFootnote 29 or served as amulets if placed unstrung in a grave.

Two further jet items from the antiquities market can be mentioned here; both are heads only, not busts. The first, a ‘fantastic ancient Roman jet amulet pendant of a Nubian head c. first century AD’ in ‘excavated condition’, was sold on ebay.ie in 2014 by a seller in Bath for £73.00. Badly cracked in places, it is elongated and hairless (with no topknot), and has a hooked nose and open mouth: height 10 mm, length 12 mm. A short length of gold wire is fitted into the horizontal piercing at the back of the head. No provenance was given. The second has been offered for some time on e-Tiquities.com.Footnote 30 Described as a pendant amulet of a head of a grotesque and dated to the later first or second century, it has many of the features of the group of three from the Rhineland – topknot, otherwise hairless head, large beak-like nose, prominent ears – but the nose is enormous and sharply hooked, making this a miniature version in jet of life-sized, beak-nosed theatrical masks and some head vases from the eastern Mediterranean.Footnote 31 It is pierced from side to side through the topknot and is 21 mm in height.

It is noticeable that the smaller black mineral busts are also the most accomplished, and this may indicate that they are the earliest. They look distinctly male, chiefly because of the prominent ears, but also because of their strong brow-ridges; the apparently hairless head sold on ebay.ie may also be male, while E8 and the silver-nippled E10 are of ambiguous gender.

Among the pendants, only those from Koninksem and Colchester are clothed. Where the former is loosely draped in a mantle, the clothing of the latter is shown by pairs of grooves that might either represent the folds of a tunic or stripes in fabric. Both tunics and overgarments, their folds shown by grooves, can be distinguished on jet portrait pendants,Footnote 32 while a female psyche on a tomb mosaic from Thyna (Henchir-Thina), Tunisia, wears a tunic and a coat-like open-fronted overgarment.Footnote 33 The lines on the Colchester pendant are rudimentary, however, and they may therefore represent both a tunic and an overgarment. Equally, stripes ran in similar positions downwards from the shoulders of the robes of both males and females in the mid-fourth century, more or less contemporary with the Colchester pendant.Footnote 34 The grooves used to show stripes/draped clothing on the figure on a mid- to late Roman bone plaque, perhaps a ritual item, from the octagonal temple site at Chelmsford are equally ambiguous (fig. 2B, 5).Footnote 35 A rounded neckline of double grooves certainly represents a tunic, while triple parallel grooves on the chest form poorly aligned sideways chevrons that may be either stripes or folds. The facial features of this figure are grooved like those of the Colchester pendant, but are in naturalistic proportions. S/he either has an elaborately curled coiffure, much like those of medieval coin portraits, or wears a headdress with curled side pieces.

DISCUSSION

The amuletic powers of jet and amber have been well rehearsed in recent years and do not need repeating here.Footnote 36 Plutarch defines a strange-looking amulet's power as being able to draw a malicious gaze away from the intended victim,Footnote 37 and the jet pendant busts belong to this practice of employing heads or masks, usually grotesque or absurd and the latter often theatrical, as guards against the evil eye, envy or the perils of the underworld. Such devices are seen across a range of objects from pottery and antefixes to amulets.Footnote 38 A pertinent example here is a bronze amulet from Boughton Aluph, Kent, in the form of a grotesque head with a small pointed skull atop male genitalia; the effectiveness of the head is reinforced by its association with the protective phallus (fig. 2B, 6).Footnote 39 The top of the skull is smooth (bald) and the face has lively well-formed eyes, a jutting jaw and a large nose; Jim Bradshaw likens it to figures of entertainers.Footnote 40 The head on a similar copper-alloy amulet from Trier has been described as that of a bald Nubian, while an unprovenanced continental find, also showing a head above male genitalia, has hair and a beard.Footnote 41

Were these jet pendants really intended to represent Africans, as is sometimes suggested? The evidence is at best ambiguous, and there is no consensus on the subject.Footnote 42 Hagen draws attention to similar heads in relief on the bezels of several jet finger-rings from Bonn, on most of which the hair and features, as on the Colchester pendant, are defined by grooves and notches.Footnote 43 The same technique is used on first- to second-century bone hairpins with heads in the form of female busts and on a lignite flute player from Bonn.Footnote 44 On these objects the materials, the areas to be embellished and the available tools all dictated the method used, and there is no suggestion that the subjects are African. The colour of the material has perhaps influenced the identification of the jet head sold on ebay.ie as that of a Nubian, while for the Colchester pendant it may have rested upon both the colour of the material and the apparently tightly curled hair. In antiquity, some stone heads of Africans with curly hair were clearly portraits of individuals and demonstrate their innate character as well as physical beauty, while others were stock images, such as ‘the sleeping slave boy’ replicated on flasks, lamps and other objects.Footnote 45

Although Henig gives the topknot as his principal reason for identifying the Colchester amber pendant as the head of an African (rejecting the idea of a tiered hairstyle),Footnote 46 there is no substantive evidence that this is the case. During the Roman Republic the wives of the 15 flamines (priests assigned to the official cults) were required to wear the tutulus, a topknot bound with cloth that seems to have originated among Etruscan matrons in the late sixth and early fifth centuries BC; and from Italy and Corsica there are mostly two-dimensional Etruscan period amber heads of females with their hair dressed in this conical style.Footnote 47 A pair of amber and gold earrings (22 mm high) from an Etruscan-Roman burial at Bettona, Italy, sheds light on various aspects of the jet busts. Each consists of an amber head of a Moor or African, grossly caricatured with slanting eyes, no nose and exaggeratedly protruding lips, held within a complex gold setting.Footnote 48 On each head tightly curled hair made of gold filigree extends down over the forehead and for some distance onto the cheeks and jaw, but leaving the ears exposed. The head is topped by a small ridged cap of gold bearing traces of blue enamel, and a ring on top of the cap provides the catch for the hoop of the earring, which is developed from a gold calyx-like cup at the neck. There are several other earrings of this type, not all identical in detail but in the same general style.Footnote 49 Their precise date is a matter for some debate: Giuseppe Cultrera proposes the second century BC as the time when the tomb was constructed, while Giovanni Becatti places the earrings, and a similar pair from Taranto, in the third century BC, the earliest date recorded for the appearance of amber earrings in the form of African heads in Italy.Footnote 50 Whatever the date, these earrings seem to hold the key to some features of the jet amulets: the cap might have become the topknot of E7/1–2, E8 and the example from Astorga, and the gold hair encasing the head and running onto the cheeks can be seen in the supposed Backenklappenhelm of E10. Indeed, only the enamelled cap and visible ears on the earrings from Bettona prevent the hair being seen as a close-fitting helmet with large cheek-pieces.

CONCLUSION

The jet busts are much later than the Italian amber and gold earrings, but they may be perceived as belonging within the same cultural tradition. Similarly, the Colchester pendant belongs within the tradition of the jet busts but has its own unique characteristics, as do others within the group. The same has been remarked upon for jet portrait pendants and jet Medusa heads, each of which differs in some way from the others.Footnote 51 Indeed, as they show clothing, the Colchester and Koninksem busts bridge the divide between jet heads and portrait pendants, and through them can be linked to the Medusa heads. Such marked distinctions in style and execution point to manufacture by several hands, some more skilled than others, and probably to several workshops as well, some competently replicating classical images in this medium and others less confident with the material and perhaps copying the products of abler artisans, or even undertaking commissions based on a verbal description, as may be the case for the Colchester pendant.

Where records survive, some of the Medusa pendants were found in burials with jewellery that suggest these are the graves of young females,Footnote 52 and the same is true for both the Colchester and Koninksem pendants. Their apotropaic effectiveness as grave deposits is reinforced by the use of a material perceived to have magical properties, but use-wear on many of these objects shows that their life as amulets began before they were buried: most noticeably two Medusa pendants from York, four portrait pendants from Cologne, bust E8 from Cologne and the Colchester pendant.Footnote 53 The same is true for the jet bears found in infant burials, where their final function as maternal guardians of the dead can be seen through surface wear to have been preceded by use as protective images for the living.Footnote 54

The Colchester black mineral bust is the only example of the form so far found in an archaeological context in Britain, and there is no reason to doubt its recovery from the North Cemetery, despite a general vagueness of contextual and associative detail. It fits within the same pattern of distribution as other jet amulets. Jet bears centre on Cologne, Colchester and Yorkshire, and Medusa heads on Cologne, York and the south-eastern seaboard of Britain from Strood in Kent up to Colchester, with one found close to Ermine Street near Brampton, Cambridgeshire, standing out as an inland outlier of the southern group.Footnote 55 With the majority of the other securely provenanced jet busts coming from Cologne, the pendant's presence in Colchester might even be called predictable, bolstered by adding the amber pendant from the Butt Road cemetery. It has been suggested that the distribution of jet bears may depend upon the movement of military personnel from the Rhineland across to Colchester and then up to Yorkshire, or, alternatively, upon élite families from the north-western provinces travelling between their estates.Footnote 56 Certainly a religious belief in the protective power of black mineral images in both life and the afterlife unites all these objects, and whatever the origin of the Colchester bust, import or British-made, it sits comfortably within the twin customs of employing grotesque images to avert envy or the evil eye and of depositing protective images in the grave to protect the dead in the underworld.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

For supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0068113X20000094.

The supplementary material comprises online appendix 1 (A brief biography of Henry Money) and online appendix 2 (Catalogue of the beads).

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Joanna Bird for drawing our attention to the Astorga bust and to Hilary Cool for her comments on the Tongeren glass and on the yellow beads (2509.12) in the Money Collection. Richard Stroud, Museum of London, kindly photographed the black mineral pendant and necklace, which was restrung by Helen Butler and Lucie Altenburg, formerly of the Museum of London. We also owe thanks to Hella Eckardt, University of Reading, for her encouragement.