Autism is a neurodevelopmental condition marked by significant heterogeneity that usually presents in early childhood and persists throughout life. It is characterised by impairments in social communication, including deficits in ability to initiate and to sustain reciprocal social interaction, and by a range of restricted, repetitive and inflexible behaviours, interests or activities that are clearly atypical or excessive for the individual's age and sociocultural context (World Health Organization 2024: 6A02). Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is an umbrella term that encompasses autism and a range of neurodevelopmental disorders that exhibit similar characteristics to autism but vary in severity and presentation (Zauderer Reference Zauderer2023).

The language used to refer to autism varies depending on the community. The authors of the Cochrane Review discussed in this article chose to use identity-first language (such as ‘autistic people’), referencing evidence that this is what is preferred by people with a diagnosis of ASD (Kenny Reference Kenny, Hattersley and Molins2016) and that person-first language might increase stigmatisation (Gernsbacher Reference Gernsbacher2017). We have therefore continued with the use of identity-first language.

The prevalence of ASD has risen over the past decade, with the World Health Organization declaring in November 2023 that around 1 in 100 children have autism (World Health Organization 2023). ASD tends to be diagnosed in males more than in females, with the most up-to-date estimated ratio being 3:1 (National Autistic Society 2024). Presentation and severity can vary widely. It can often be accompanied by other psychiatric comorbidities. In terms of therapeutic aims and approaches, psychosocial and behavioural therapies are considered the first-line evidence-based treatments for people with a diagnosis of ASD. There are various music therapy approaches for working with autistic people, which can be person-led or relational and are directed by the person's strengths and resources (Carpente Reference Carpente2009). Therapy can be provided in individual (one-to-one), group-based or peer-mediated interventions. It can involve active music-making, listening to music played by the therapist, movement activities or storytelling (Geretsegger Reference Geretsegger, Fusar-Poli and Elefant2022). Often the target is to develop social interaction and understanding.

What does previous evidence tell us?

Music therapy for autistic people has been used since the 1950s and there are neurobiological and psychosocial theories that aim to explain how it is beneficial, for example by enabling non-verbal social exchange (Fusar-Poli Reference Fusar-Poli, Thompson, Lense, Matson and Sturmey2022).

The initial Cochrane Review on music therapy (Gold Reference Gold, Wigram and Elefant2006) concluded that it might help autistic people improve their communication skills. In a sample of 24 participants it identified an improvement in verbal and gestural communicative skills compared with placebo. It only looked at the short-term effect of brief interventions. A second review (Geretsegger Reference Geretsegger, Fusar-Poli and Elefant2014) had a larger sample (165 individuals) and examined short- (1 week) and medium-term (7 months) effects of music therapy. It concluded that music therapy may help children with autism improve their skills in social interaction, verbal communication, initiating behaviour and social-emotional reciprocity. It identified a need for more research with larger samples, using standardised scales.

There have been other systematic reviews, but as Geretsegger et al (Reference Geretsegger, Fusar-Poli and Elefant2022) point out in their latest update (which we discuss here), these have methodological flaws (e.g. Whipple Reference Whipple, Kern and Humpal2012) or are not generalisable (e.g. Shi Reference Shi, Lin and Xie2016). Furthermore, since these were published, knowledge about ASD has increased and there have been many new studies investigating music therapy and ASD.

Summary of this month's Cochrane Review

This third update (Geretsegger Reference Geretsegger, Fusar-Poli and Elefant2022) included 26 studies, compared with 10 in the 2014 review, and therefore participant numbers were increased. Participants ranged in age from 2 years to young adult; most studies included only children (2–12 years old), although one included only adults (mean age of 25; Mateos-Moreno Reference Mateos-Moreno and Atencia-Doña2013). Overall there was moderate-certainty evidence that, compared with placebo, music therapy is probably associated with an increased chance of global improvement for autistic people, that it likely helps to reduce total autism symptom severity and improve quality of life, and that it probably does not increase adverse events immediately after the intervention. The certainty of evidence of a difference for the other three primary outcomes reviewed (non-verbal and verbal communication and social interaction) was low or very low. The applicability of findings is limited to the age groups specified (not older than young adult). The evidence was limited in identifying long-term effects.

Specific areas of focus for discussion

Method

The purpose of the review was to assess the impact of music therapy on autistic people. Music therapy was compared with placebo therapy or standard care. Music therapy covers a range of therapeutic techniques, which were specified in each included study. Comprehensive searches identified the included studies, which comprised randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi-randomised trials and controlled clinical trials, RCTs being the gold standard (Box 1).

BOX 1 Randomised controlled trials

A randomised controlled trial (RCT) is a prospective study that assesses the effectiveness of an intervention against a comparator. The researchers must carefully select the intervention and comparator groups and the outcomes of interest. Participants are randomised and allocated to a group – intervention versus comparator (no intervention/control). This process reduces the risk of bias and provides a rigorous tool to examine cause–effect relationships. Randomisation acts to balance observed and unobserved participant characteristics between groups. To minimise bias, RCTs are often masked (blinded) so that participants, investigators and assessors do not know which group the participants are in:

• single-blind trial – only the participants are unaware of their assigned group

• double-blind – participants and study staff are unaware of the assigned groups

• triple-blind – participants, study staff and data analysers are unaware of the assigned groups

Outcome measures were broadened in this review to capture all relevant potential outcomes. The review also included standardised and non-standardised instruments to measure outcomes. Rating scales were included only if the instrument was either self-report or completed by an independent rater or relative and not by the therapist. There is an argument that reports completed by relatives could also be subject to performance bias and ideally all outcomes should be assessed by an independent rater.

The sample (n = 1165) was much larger than in previous reviews, and although international studies were included, most were conducted in North America. It included non-verbal and verbal children with varied cognitive and adaptive abilities, ranging from mild to severe autism. Although the review aimed to include adolescents and adults, the majority of studies involved children aged 2–12, and therefore it is questionable whether findings can be applied to adolescents and adults.

The follow-up time points varied but the mean follow-up was 3 months. The mean duration of intervention was 2.5 months. More research would be beneficial to identify duration of effect.

Data selection and extraction was clearly explained and recorded. The risk of bias was assessed using Cochrane's Risk of Bias 1 (RoB 1) tool (Higgins Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green2011).

The authors used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) system when reviewing the evidence; this system has been adopted by Cochrane for assessing the certainty (or quality) of a body of evidence. The GRADE approach specifies four levels of certainty for a body of evidence for a given outcome: high, moderate, low and very low. GRADE assessments of certainty are determined through consideration of five domains (Schünemann Reference Schünemann, Higgins, Vist, Higgins, Thomas and Chandler2023), as outlined in Box 2.

BOX 2 The five domains considered in GRADE assessments of certainty of evidence

• Risk of bias – graded as low, some concerns or high

• Inconsistency – degree of variability in results between studies

• Indirectness – do the majority of studies address the PICO (Patient, population or problem; Intervention; Comparison; Outcome)?

• Imprecision – risk of random errors (Castellini Reference Castellini, Bruschettini and Gianola2018)

• Publication bias – publishing certain studies and not publishing others, e.g. publishing those with positive and/or significant results and not publishing those with negative or no significant results

Results

Music therapy was compared with standard care, or with a ‘placebo’ therapy that attempted to control for all non-specific elements of music therapy. Most outcomes were assessed during intervention and immediately post-intervention, although one study followed up over the 1- to 5-month period post-intervention (Porter Reference Porter, McConnell and McLaughlin2017) and one followed up over the 1–5 months and 6–11 months post-intervention (Bieleninik Reference Bieleninik, Geretsegger and Mössler2017).

Study results showed a large effect in favour of music therapy on social interaction during the intervention. There was no sustained effect immediately post-intervention, or in the 1- to 5-month and 6- to 11-month follow-up periods. There was also a large effect in favour of music therapy on non-verbal communication during the intervention, but this was not maintained post-intervention. The authors note that the certainty of the evidence using the GRADE system was rated as ‘low’ for both outcomes, and therefore their confidence in the effect estimate is limited. They also note a moderate certainty in the large effect size in favour of music therapy on reducing total autism symptom severity post-intervention and during the 1- to 5-month follow-up period, but this was not maintained during the 6- to 11-month period. Global improvement as an outcome was more likely to occur with music therapy than with comparison interventions, but this was not sustained over the 1–5 and 6–11 months post-intervention.

There was no difference between the music therapy and comparison groups on verbal communication outcomes during and post-intervention. Music therapy probably exerted a small to medium improvement in quality of life when compared with comparator groups post-intervention, but this was not maintained during the 6- to 11-month follow-up.

Adverse events data were available in only two studies (Bieleninik Reference Bieleninik, Geretsegger and Mössler2017; Porter Reference Porter, McConnell and McLaughlin2017), only one of which reported any events and it identified no differences between the music therapy and the control groups (Bieleninik Reference Bieleninik, Geretsegger and Mössler2017).

Finally, as regards the secondary outcomes, a large effect in favour of music therapy was identified for adaptive behaviour during the intervention (but not post-intervention or on follow-up) and for identity formation 1–5 months post-intervention. No difference between music therapy and comparison groups was identified in quality of family relationships, depression and cognitive ability.

Bias

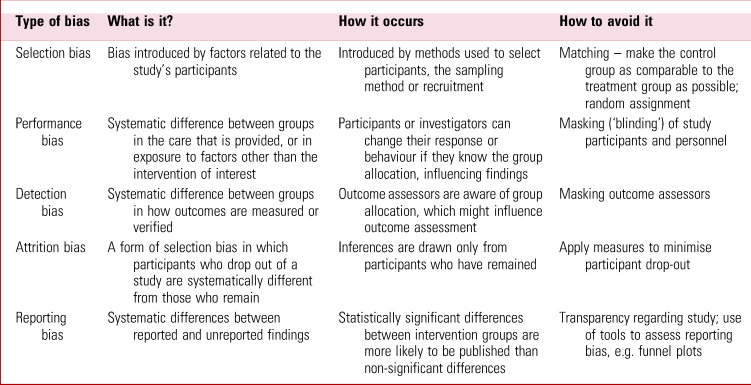

The risk of bias was assessed independently by four of the review authors using RoB 1 (Higgins Reference Higgins, Altman, Sterne, Higgins and Green2011), specifically looking at selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attritional bias and other bias (Table 1). They thoroughly assessed the risk of each bias for each study, classifying into low, high and unclear risk. However, the use of the original Cochrane risk-of-bias tool (RoB 1) rather than the updated RoB 2 (Sterne Reference Sterne2019) which is now recommended for use in Cochrane reviews (Higgins Reference Higgins, Thomas and Chandler2023), is a limitation of the study.

TABLE 1 Different types of bias in clinical trials

Sources: Florczak (Reference Florczak2022); Popovic & Huecker (Reference Popovic and Huecker2024).

The authors found an unclear risk of bias in the masking (‘blinding’) category in all of the included reviews. Owing to the nature of the intervention, it would be difficult to mask the participants and therapists to the group they were in as music is something we consciously experience and therefore is difficult to mask someone to.

The authors attempted to address reporting bias by using funnel plots to determine the relationship between effect size and study precision when 10 or more studies were pooled for an outcome. They used sensitivity analyses to determine the impact of studies rated as having a high risk of attrition bias (if drop-out rates were above 30%). The risk of performance bias was unknown in all studies. There was a low risk of reporting bias, attrition bias and of other bias in most studies. Detection bias and selection bias were unknown in at least 50% of the included studies, which might have influenced the results to an unknown degree.

Applicability and next steps

The overall evidence found in the review is of very low to moderate certainty, and therefore future research may change the findings. The authors suggest that more research with adequate design, i.e. producing reliable evidence, looking at areas that matter to autistic people is needed.

It is important to consider reliability and validity of evidence (Box 3). The authors reference reliability in their section on masking (blinding) and make reference to external validity in the context of applicability of findings to clinical practice. However, given the findings outlined above and little evidence of long-term benefit this might be premature.

BOX 3 Reliability and validity

Reliability – if research is repeated under the same circumstances, would the same results be obtained? The consistency of results is checked across various domains. A reliable measurement is not always valid; the results might be able to be reproduced but they may not be accurate.

Validity – do the results really measure what they are supposed to measure? The results are checked against established evidence and measures of the same concept. A valid measurement is generally reliable; if a test has produced accurate results the results should be able to be replicated.

(Adapted from Middleton Reference Middleton2023)As regards future research, the authors propose that because long-term outcomes of therapy matter to autistic people and their families, it is important to specifically examine how long the effects of music therapy last, as only two studies conducted longer-term follow-up. They recommend that future trials of music therapy in this area should be: ‘(1) pragmatic; (2) conscious of types of music therapy; (3) conscious of relevant outcome measures; and (4) include long-term follow-up assessments’ (Geretsegger Reference Geretsegger, Fusar-Poli and Elefant2022).

We searched PubMed for relevant articles published after this Cochrane Review. A paper by MacDonald-Prégent et al (Reference MacDonald-Prégent2024) using data from a randomised controlled trial that compared play-based and music-mediated interventions reported greater therapeutic benefit for the music-mediated intervention in children with lower verbal IQ. A paper by Bhandarkar et al (Reference Bhandarkar, Salvi and Shende2024) discusses the advanced effects of music therapy in autism, such as activating neurochemical reward pathways. A proposed trial by Ruiz et al (Reference Ruiz2023) aims to determine whether music therapy leads to improvements in social communication and functional brain connectivity when compared with play-based therapy.

We suggest that further research should pay particular attention to addressing bias, in particular masking assessors and utilising standardised outcomes to minimise the risk of detection bias. Masking participants continues to be a challenge, given the nature of music therapy, as previously mentioned. Further research questions could include: determining the best setting for individuals to receive their therapy, the optimum frequency of music therapy sessions and reviewing any long-term benefits to provide more information about the feasibility and effectiveness of music therapy in clinical practice.

Data availability

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Author contributions

Both authors were involved in the topic selection and contributed equally to this article.

Funding

This work received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

None.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.