Introduction

Located at the south-eastern margin of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar are located at the crossroads of three major biodiversity hotspots: the Himalayan hotspot, the Indo-Burma hotspot and the Southwestern Chinese Mountain hotspot (Marchese Reference Marchese2015). Therefore, the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar harbour highly diverse assemblages of faunal elements from two larger zoogeographic regions, the Palearctic and the Oriental (Indo-Malayan) region. Along the elevational gradient, local species assemblages occupy different ecological niches in a great number of different terrestrial ecoregions (Wikramanayake et al. Reference Wikramanayake, Dinerstein and Loucks2002). At 5,881 m above sea level, Myanmar’s highest mountain Hkakabo Razi is located in the centre of the third largest of 55 important bird areas (IBA) in Myanmar (country profile of Myanmar; Chan Reference Chan2004). At a larger spatial scale, the Hkakabo Razi region is part of the Eastern Himalaya Endemic Bird Area (EBA 130) (Stattersfield et al. Reference Stattersfield, Crosby, Long and Wege2005). A first assessment of avian species richness at Hkakabo Razi was conducted by Rappole et al. (Reference Rappole, Aung, Rasmussen and Renner2011): A long-term study over five expeditions listed no less than 431 bird species in this region. In the course of long-term monitoring this number has been raised to 441 bird species observed at Hkakabo Razi (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015). An independent study covering four annual surveys (2015–2017) in the Putao region (Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Kyaw, Li, Zhao, Zeng, Swa and Quan2017) recorded a total number of 319 bird species and confirmed a mid-domain effect of species richness with highest diversity at average elevations (Stevens Reference Stevens1992, Acharya et al. Reference Acharya, Sanders, Vijayan and Chettri2011).

The Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar are also home to a number of globally threatened vertebrate species; mammals: the recently described Myanmar snub-nosed monkey Rhinopithecus strykeri (Geissmann et al. Reference Geissmann, Lwin, Aung, Aung, Aung, Hla, Grindley and Momberg2011) and two endemic deer species of the genus Muntiacus (Rabinowitz et al. Reference Rabinowitz, Myint, Kaing and Rabinowitz1999); birds: the critically endangered White-billed Heron Ardea insignis (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015), or the Rusty-bellied Shortwing (Brachypteryx hyperythra; compare species factsheet BirdLife International (2018). Brachypteryx hyperythra is fairly common at Hkakabo Razi, thus except for some fragmented and small populations in Nepal and north-east India, the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar are among the last refuges for this species. Among Myanmar’s endemic birds (see list at http://lntreasures.com/burma.html) most are typical lowland species and distributed farther south, such as the recently rediscovered Jerdon’s Babbler Chrysomma altirostre (Rheindt et al. Reference Rheindt, Tizard, Pwint and Lin2014), or even restricted to single sites farther south such as Nat Ma Taung, also known as Mount Victoria (e.g. the White-browed Nuthatch, Sitta victoriae, or the endemic subspecies of Black-throated Tit, Aegithalos concinnus sharpei). Other Myanmar endemics such as the endangered Hooded Treepie Crypsirina cucullata or the Burmese Bushlark Mirafra microptera have not yet been recorded at Hkakabo Razi, though the habitat in theory could fit for both species. However, one narrow-range endemic of the northern mountain forests is the Naung Mung Wren-babbler Rimator naungmungensis. Though subject to lively debate since its scientific description by Rappole et al. (Reference Rappole, Renner, Shwe and Sweet2005) its species status is well justified based on the results of genetic analyses (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Kyaw, Milensky and Päckert2018).

Previous field explorations to Hkakabo Razi resulted in several new bird taxa including the Ashy-headed Babbler Alcippe cinereiceps hkakaboraziensis and Abbott’s Babbler Malacocincla abbotti kachinensis (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015). Furthermore, preliminary data from comparative integrative analyses using morphological, bioacoustic and genetic characters showed that cryptic diversity is still underestimated for the Hkakabo Razi region, in other groups such as babblers (Moyle et al. Reference Moyle, Andersen, Oliveros, Steinheimer and Reddy2012), cupwings Pnoepyga spp. (Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Martens, Liang, Hsu and Sun2013) and leaf-warblers (Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Sun, Peterson, Holt, Strutzenberger, Martens, Päckert, Martens and Sun2016).

For several passerine target species of our study, we provide evidence of genetic distinctiveness of local populations in the Hkakabo Razi region. Some of these newly discovered genetic lineages are candidates for future study as possible new taxa. This information is relevant for conservation genetics and will be used in the currently ongoing nomination process for a UNESCO World Natural Heritage Site, the "Hkakabo Razi Landscape".

Material and methods

Study region and study sites

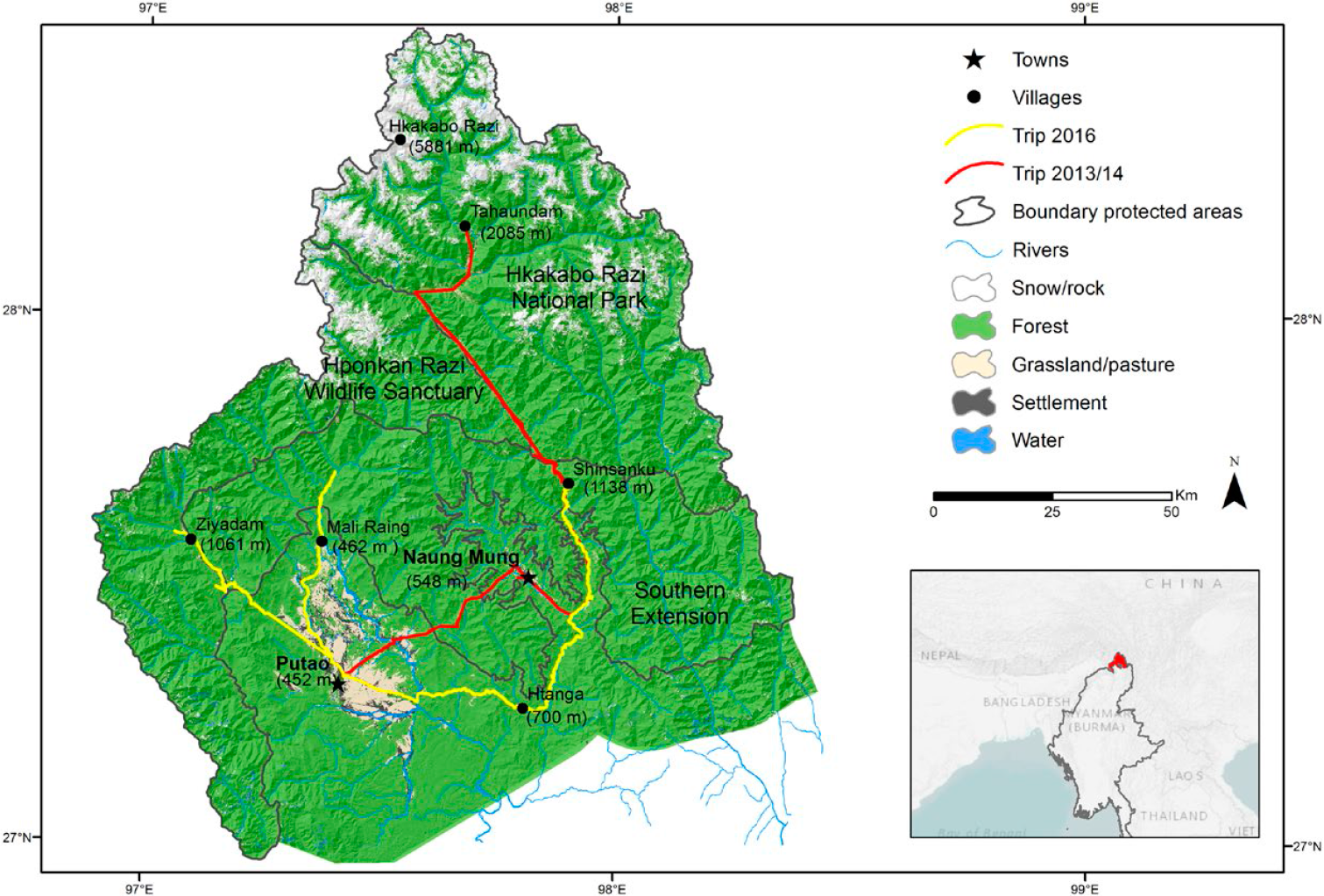

The study region is located in the northernmost tip of Myanmar and covers the Hkakabo Razi National Park, the Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary and the tentative Southern Extension of the Hkakabo Razi National Park (proposed boundaries as of August 2016 which are subject to changes (Figure 1). All three protected areas together are currently under consideration as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, tentatively suggested to be listed under criteria (ix) and (x) of the convention.

Figure 1. Map of the study region and the protected areas in the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar including itineraries during expeditions in 2013/2014 and 2016; elevations (in meters ASL) of study sites and highest summits given in brackets.

The study area within the region covered five major sites: (i) Ziyadam/Wanglaimdam in Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary, (ii) the Mali Raing and (iii) the Htanga-Shinsanku area in the Southern Extension, (iv) the higher elevations in the Hkakabo Razi National Park, and (v) the Babulontan Range in the Namti-Naung Mung area (Figures 1 and 2). Except for the very high elevations (> 3,000 m) all areas were covered by two field trips (see map in Figure 1). The study region has a unique constellation of land cover and land use types which are mainly stacked by elevational bands and form a diverse set of habitats for birds (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Leimgruber and Kelly2007).

Figure 2. Study sites in the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar; a) view at Hkakabo Razi; b) grassland and subtropical forest edge at Mali Raing; c) riverside near Ziyadam; d) Ziyadam, local village (Photos by Marcela Suarez-Rubio and Swen C. Renner).

Sampling

For a pilot genetic assessment, we chose 16 passerine species locally recorded at Hkakabo Razi (Rappole et al. Reference Rappole, Renner, Shwe and Sweet2005, Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015). The basic material for this study consisted of blood samples collected during a field trip from 31 January to 27 March 2016. During this trip we visited three sites; the Ziyadam area within Hponkan Razi Wildlife Sanctuary (six capture days), the Mali Raing area (nine capture days) and the Htanga-Shinsanku area (11 capture days). Further material (blood samples) were collected during another field trip to Hkakabo Razi (15 December 2013 to 30 January 2014, all in Hkakabo Razi National Park from Naung Mung to Tahaundam, with 28 capture days, 10 nets for six consecutive hours per day) and from museum collections (Senckenberg Natural History Collections Dresden [SNSD]; Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History [USNM]).

For a pilot screening of intraspecific genetic differentiation, we focussed on species (taxon pairs) with considerable subspecific variation between populations from Myanmar and those from adjacent Himalayan and Chinese mountain ranges (based on current systematics and morphology). For some of our target species, intraspecific genetic diversification was already suspected from analysis of very few samples (n < 5 per species; e.g. core babblers studied by Moyle et al. Reference Moyle, Andersen, Oliveros, Steinheimer and Reddy2012). Furthermore, we used DNA barcoding as a control for correct identification of cryptic species in the field with a broader choice of target species from our total sampling (143 samples from 45 species). Due to their subtle phenotypic distinctiveness, cryptic species are not easily distinguished from their closest relatives without additional data from vocalisations or genetics (Irwin et al. Reference Irwin, Alström, Olsson and Benowitz-Fredericks2001, Bickford et al. Reference Bickford, Lohman, Sodhi, Ng, Meier, Winker, Ingram and Das2007), such as in the case of golden-spectacled warblers of the former Seicercus burkii complex (Alström and Olsson Reference Alström and Olsson1999, Martens et al. Reference Martens, Eck, Päckert and Sun1999, Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Martens, Sun and Veith2004, Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Alström, Ericson and Sundberg2005), today Phylloscopus burkii and allies (del Hoyo and Collar Reference del Hoyo and Collar2016). For the eight species-level taxa of this group, DNA barcode reference sequences were recently published (Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Sun, Peterson, Holt, Strutzenberger, Martens, Päckert, Martens and Sun2016). To date, five of these species have been listed for our study site at Hkakabo Razi, however species identification according to phenotypes is highly problematic and these records needed confirmation from molecular markers. We also aimed at verifying species identification in case of a few doubtful records from the field lists, such as Indomalayan species like the Mountain Warbler Phylloscopus trivirgatus, or South-East Asian species like the Grey-cheeked Fulvetta Alcippe morrisonia (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015). The latter species has a widespread distribution across South-East Asia, however, the northern Myanmar mountain forests are located at the extreme northern edge of the species’ range. If the species was present in the northern mountain forests of Myanmar, the local population at Hkakabo Razi would be expected to belong to subspecies A. m. yunnanensis, which represents two closely related lineages so far known only from Yunnan and south-west Sichuan (Song et al. Reference Song, Qu, Yin, Li, Liu and Lei2009).

With several competing bird species lists of the world (Dickinson and Christidis Reference Dickinson and Christidis2014, del Hoyo and Collar Reference del Hoyo and Collar2016, Gill & Donsker Reference Gill and Donsker2019), avian taxonomy and systematics has become increasingly confusing in certain groups. We follow the taxonomy used by BirdLife International, based on del Hoyo and Collar (Reference del Hoyo and Collar2016) for passerines. However, due to recent taxonomic changes particularly in the speciose families of babblers, the taxonomy in published species lists for the study region (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015) might strongly differ from the taxonomic standard applied for this study. To avoid misunderstandings and confusion we provide synonymies for all our target species in Table S1 in the online supplementary material. Our target groups were babbler species from the families Pellorneidae, Leiotrichidae, Timaliidae (Alcippe, Napothera, Pellorneum, Pomatorhinus, Rimator, Schoeniparus, Turdinus, Trichastoma), cupwings (Pnoepygidae: Pnoepyga), leaf-warblers (Phylloscopidae: Phylloscopus), bush warblers (Scotocercidae: Abroscopus, Tesia) and bulbuls (Pycnonotidae: Alophoixus). A full list of sampled material and sequence data inferred from GenBank for comparison can be found in supplementary Tables S2 and S3.

All samples were taken in accordance with national Myanmar law and the animal protection laws of the European Union. All experimental protocols follow the national laws of Myanmar and have been approved by following the rules for the Nagoya Protocol, represented by the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environmental Conservation (MONREC; details in Acknowledgements). Access to the protected areas was granted by the Forest Department of MONREC under the contract with UNESCO ("Safeguarding Natural Heritage in Myanmar within the World Heritage Framework – Phase II 504MYA4001") for all fieldwork.

Marker choice

In conservation genetics, DNA barcoding using the standard marker cytochrome-oxidase I (COI) is often the method of choice for a first pilot screening of undiscovered genetic variation. The barcode marker COI has been proven to be a useful tool for species identification in birds (Hebert et al. Reference Hebert, Stoeckle, Zemlak and Francis2004, Kerr et al. Reference Kerr, Birks, Kalyakin, Red’kin, Koblik and Hebert2009, Barreira et al. Reference Barreira, Lijtmaer and Tubaro2016). Furthermore, DNA barcoding helped uncover intraspecific phylogeographic structure of some Asian bird species (Song et al. Reference Song, Qu, Yin, Li, Liu and Lei2009, Tritsch et al. Reference Tritsch, Martens, Sun, Heim, Strutzenberger and Päckert2017). However, barcode records of the Asian avifauna are still rather scarce, with the exception of the well-screened Japanese avifauna (Saitoh et al. Reference Saitoh, Sugita, Someya, Iwami, Kobayashi, Kamigaichi, Higuchi, Asai, Yamamoto and Nishiumi2015). Further sequence data input to the Barcode of Life Database (BOLD) came from a limited number of studies from Korea (Park et al. Reference Park, Yoo, Jung and Kim2011), South-East Asia (Lohman et al. Reference Lohman, Prawiradilaga and Meier2009) and China (Huang and Ke Reference Huang and Ke2014). Therefore, for several Asian species or even whole genera few COI sequences from previous studies are available for comparison. Our study provides the first COI sequences for several species and even a first complete barcode inventory for some avian genera, such as Pnoepyga cupwings.

Because of the general scarcity of barcode sequences for Asian bird species, we also sequenced the mitochondrial cytochrome-b and/or ND2 for some study groups depending on the number of sequences available at GenBank for comparison. For the White-throated Bulbul Alophoixus flaveolus we amplified and sequenced ATP synthase membrane subunit 6 (ATP6) for selected samples for comparison with sequence data from Fuchs et al. (Reference Fuchs, Ericson, Bonillo, Couloux and Pasquet2015).

For a firm inclusion of newly detected genetic lineages in a phylogenetic tree, we performed multi-locus analyses for some groups for which comprehensive multi-locus data sets were already available. We therefore amplified and sequenced further nuclear introns for selected samples of target species. Marker choice depended on sequence data sets available from previous studies and the following combinations of nuclear introns were analysed: 1) ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) introns 6 and 7 and myoglobin (myo) intron 2 for leaf warblers and bush warblers (Alström et al. Reference Alström, Hohna, Gelang, Ericson and Olsson2011; see their supplementary Table 8); 2) β-fibrinogen intron 5 (fib5), muscle skeletal receptor tyrosine kinase (MUSK) intron 3 and transforming growth factor β2 (TGFB2) intron 5 for babblers (Moyle et al. Reference Moyle, Andersen, Oliveros, Steinheimer and Reddy2012); for comparison with our sequences from Myanmar we used their complete multi-locus alignment, downloaded from Dryad: doi:10.5061/dryad.100jc764).

Lab protocols

For DNA extraction from blood samples, we used the innuPREP BloodDNA Mini Kit (Analytik Jena AG, Germany). For amplification of the barcoding marker (COI), we used standard primers BirdF1 and BirdR1 (Hebert et al. Reference Hebert, Stoeckle, Zemlak and Francis2004), each one modified with a 5’ M13 tail (forward-primer BirdF1-tl: TGTAAAACGACGGCCAGTTTCTCCAACCAC-AAAGACATTGGCAC, reverse-primer BirdR1-tl: CAGGAAACAGCTATGACACGTGG-GAGATAATTCCAAATCCTGG). The PCR protocol for the barcoding marker was 94°C for 5 min followed by 5 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 50°C for 1:30 min and 72°C for 1:30 min followed by 30 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 51°C for 1:30 min and 72°C for 1:30 min with a final extension at 72°C for 5 min (modified from Tritsch et al. Reference Tritsch, Martens, Sun, Heim, Strutzenberger and Päckert2017). Along with the barcode marker we amplified the mitochondrial cytochrome-b for at least one sample of each taxon investigated with the primer combination O-L14851 (5’-CCT ACC TAG GAT CAT TCG CCC T-3’) and O-H16065 (5’-AGT CTT CAA TCT TTG GCT TAC AAG AC-3’ (Weir and Schluter Reference Weir and Schluter2008)). The PCR protocol for cytochrome-b was 94°C for 10 min followed by 35 cycles of 92°C for 1 min, 53°C for 1 min and 72°C for 2 min with a final extension at 72°C for 10 min. Further information on primer combinations used for PCR and sequencing of further mitochondrial markers and nuclear introns is provided in Table 1.

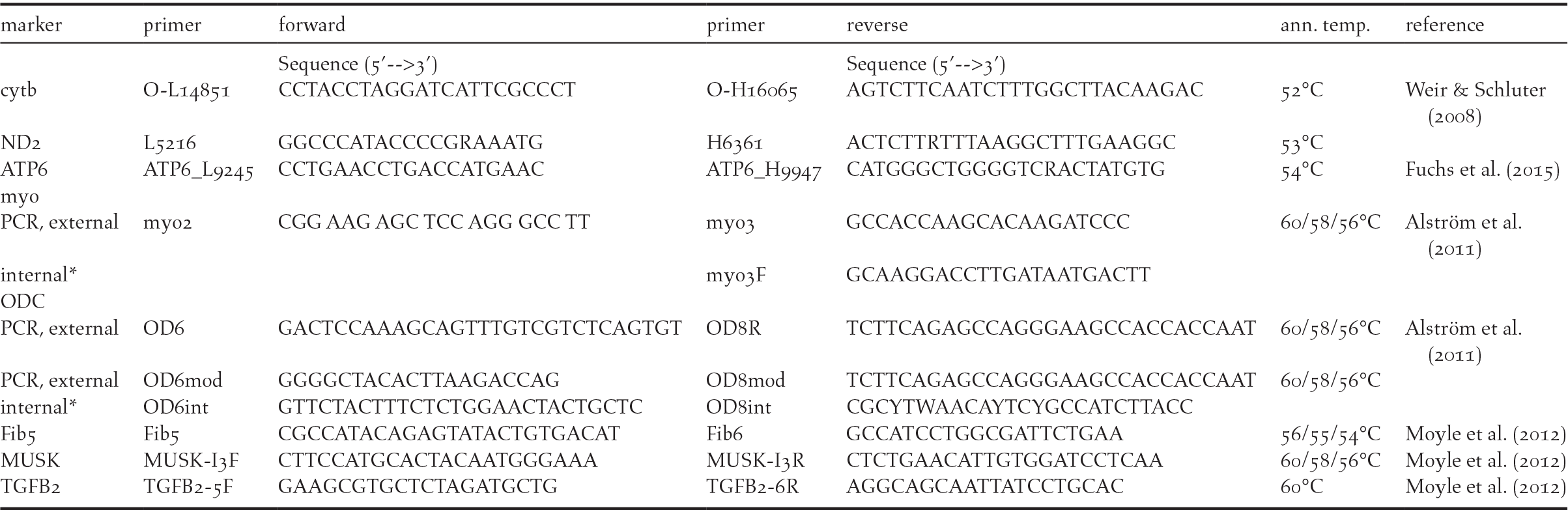

Table 1. Primer combinations used for amplification and sequencing; *= internal primer used for sequencing only; ann. temp.= annealing temperature.

PCR products were purified using ExoSapit and sequenced on an ABI 3130xl capillary sequencer (Applied Biosystems). Sequencing of the barcoding marker was performed using the non-modified primer pair BirdF1 and BirdR1 (Hebert et al. Reference Hebert, Stoeckle, Zemlak and Francis2004). The sequences were aligned manually using MEGA version 5.10 (Tamura et al. Reference Tamura, Peterson, Peterson, Stecher, Nei and Kumar2011) and examined by eye and controlled for possible stop codons or frame shifts in coding sequences.

Sequence analysis

For a first assessment of intraspecific diversification, we reconstructed single-locus phylogenies of mitochondrial markers (COI and/or cytochrome-b depending on the number of sequences available for comparison). We included further sequences downloaded from GenBank for comparison into our single-marker analysis, e.g. for scimitar-babblers Pomatorhinus from Reddy and Moyle (Reference Reddy and Moyle2011) and from Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Li, Zou, Lei, Liang, Yang and Yang2014); for the Puff-throated Babbler Pellorneum ruficeps from Robin et al. (Reference Robin, Vishnudas, Gupta and Ramakrishnan2015) (for a full documentation of GenBank sequences used for comparison see Table S3). We reconstructed single-locus trees using Bayesian inference of phylogeny (BI) with MrBAYES vers. 3.2.3 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck Reference Ronquist and Huelsenbeck2003). Data sets were generally partitioned by codon position under the GTR+Gamma+Invariant Sites (GTR +Γ+I) substitution model. We allowed the overall rate to vary between partitions by setting the priors < ratepr = variable > and model parameters such as gamma shape, proportion of invariable sites and the rate matrix were unlinked across partitions. We conducted two runs per analysis with one cold and three heated MCMC chains of 1,000,000 generations with trees sampled every 100 generations and a burn-in of 3,000 trees. In case of intraspecific lineage splits, genetic distances between populations from Myanmar and those from adjacent countries were calculated with MEGA v. 6.06 (Tamura et al. Reference Tamura, Stecher, Peterson, Filipski and Kumar2013). Genetic distances between populations are based on uncorrected p-distances of cytochrome-b sequences.

Multi-locus phylogenies were reconstructed with BEAST based on combined datasets of mitochondrial genes and nuclear introns (marker choice depending on the target family, see above). Substitution model choice and partition of the data set were applied according to the original multi-locus studies, compare for babblers (Moyle et al. Reference Moyle, Andersen, Oliveros, Steinheimer and Reddy2012), for bush warblers (Alström et al. Reference Alström, Hohna, Gelang, Ericson and Olsson2011) and for cupwings (Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Martens, Liang, Hsu and Sun2013). We ran BEAST for 30,000,000 generations (parameters were logged and trees sampled every 1,000 generations) under the uncorrelated lognormal clock model for all loci with the "auto-optimize" option activated and a birth-death process prior applied to the tree. The log files were examined with Tracer 1.6 (Rambaut et al. Reference Rambaut, Drummond and Suchard2014) in order to ensure effective sample sizes (ESS; which yielded reasonable values for all parameters after 30,000,000 generations) and trees were summarized with TreeAnnotator v1.4.8 (posterior probability limit = 0.5) using a burn-in value of 3,000 trees and the median height annotated to each node.

For a rough estimate of divergence times, we applied a time calibration using an empirical rate estimate for cytochrome-b of 0.0105 substitutions per site per lineage per million years (Weir and Schluter Reference Weir and Schluter2008). All obtained phylograms were edited in FigTree vers. 1.4.2. For species with adequate intraspecific sampling, we reconstructed haplotype networks of mtDNA markers using TCS version 1.2.1 (Clement et al. Reference Clement, Posada and Crandall2000). Uncorrected genetic distances (p-distances) were calculated with MEGA v. 6.0, all p-distance values refer to pairwise comparisons of cytochrome-b sequences.

Newly generated sequences from this project were deposited at GenBank under accession numbers MK547438–MK547510, MK56716–5MK567188, MK598855– MK599135, MK609929–MK609959. The entire sequence data sets for mitochondrial markers (COI, cytochrome-b, ND2) have been uploaded to BOLD and are available including all sample metadata under project “UNMYA UNESCO Myanmar”.

Results

Intraspecific diversification was remarkable in almost all our target species. We found genetic splits between populations from Myanmar and those from adjacent regions corresponding with p-distance values greater than 3% (cytochrome-b) in 13 out of 16 target taxa (Table 2). In two additional species, we found a distinct mitochondrial lineage in Myanmar, though genetic distances ranged at lower values between 1 and 2.5%. Only a single species (the White-throated Bulbul Alophoixus flaveolus) did not show any intraspecific differentiation (neither for cytochrome-b nor for ATP6; Figure S1). Genetic barcoding found misidentifications in five species that had been confused with a phenotypically very similar relative. We comment on these few cases in the following section.

Table 2. Intraspecific differentiation between populations of target species from Hkakabo Razi, Myanmar, and those from adjacent regions (mitochondrial DNA, cytochrome-b, in %; except Pellorneum albiventre*= p-dist refers to ND2 due to a lack of cytb data); potential candidates for species splits have genetic distances of p-dist > 3% (see methods).

Babblers (Timaliidae, Leiotrichidae, Pellorneidae)

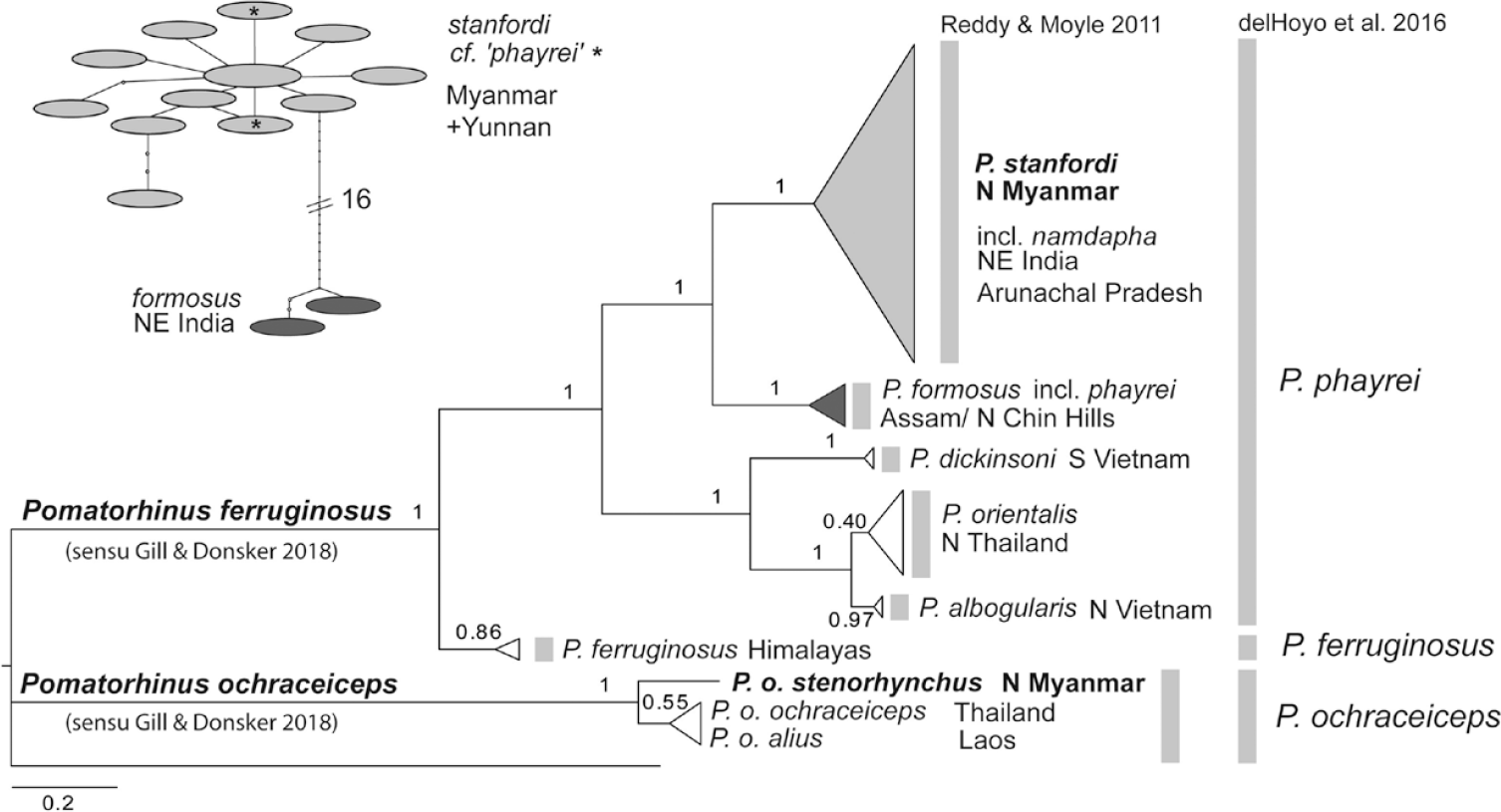

Phylogenetic structure could be found in nearly all our target species (for a phylogeny of the whole babbler data set, see Figure S2). In Timaliidae, the Red-billed Scimitar-babbler Pomatorhinus ochraceiceps and Brown-crowned Scimitar-babbler P. phayrei could be genetically identified in our sampling. Most specimens of the latter species were identified as belonging to subspecies P. p. stanfordi in the field, only two individuals were identified as nominate P. p. phayrei. Because occurrence of this more southerly distributed subspecies was doubtful, we also genotyped these two specimens. All P. phayrei sequences from the study site (ssp. stanfordi) formed one haplotype cluster that was separated by 16 substitutions (equalling a p-distance of 2.7%; Table 2) from two haplotypes of the north-east Indian sister taxon P. p. formosus (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Molecular phylogeny (Bayesian inference of phylogeny, MCMC chain length 1,000,000 generations, node support from posterior probabilities shown) of scimitar-babblers: two species Pomatorhinus phayrei and P. ochraceiceps according to classification by (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015; Gill and Donsker 2018) indicated at branches (two alternative classifications that distinguish three and seven species, respectively, indicated at the right of each clade), based on 1041 bp of mitochondrial cytochrome-b; our data and data set by Reddy and Moyle (Reference Reddy and Moyle2011) (tree rooted with a sequence of Pomatorhinus superciliaris; upper left: haplotype network for the Sino-himalayan crown clade of ssp. formosus and stanfordi, asterisk denotes haplotypes of two specimens from Hkakabo Razi tentatively identified as ssp. phayrei in the field.

Genetic distances between P. phayrei and its sister species the Coral-billed Scimitar-babbler P. ferruginosus from the Himalayas amount to 3.4–4.2%. These two sister species (five clades; Figure 3) differed from their closest relative, the Red-billed Scimitar-babbler by 8.8–9.9%. In the latter species, P. o. stenorhynchus from Myanmar differed from populations from Thailand (nominate ssp. ochraceiceps) and from Laos (ssp. alius) by a p-distance of 1.1% (Figure 3; Table 2). For further details on intraspecific diversification and paraphyly in the Streak-breasted Scimitar-babbler P. ruficollis and the White-browed Scimitar-babbler P. schisticeps, as evident from the data set by Moyle et al. (Reference Moyle, Andersen, Oliveros, Steinheimer and Reddy2012) see Discussion.

For Leiotrichidae, we analysed a larger sample set of one fulvetta species that had been preliminarily identified as the Grey-cheeked Fulvetta Alcippe morrisonia in the field. However, all our genotyped samples (n = 36) turned out to be individuals of the Nepal Fulvetta A. nipalensis. A cluster of 16 different haplotypes from our study site differed from a sequence from the Eastern Himalayas (Arunachal Pradesh, India) by 36 substitutions (equalling a p-distance of 6.7%; Table 2; Figure 4A).

Figure 4. Phylogeographic structure in three South-East Asian babbler species, haplotype networks based on mitochondrial cytochrome-b; A) Alcippe nipalensis, B) Trichastoma tickelli, C) Schoeniparus rufogularis; Pellorneum ruficeps (n = 20, 820 bp).

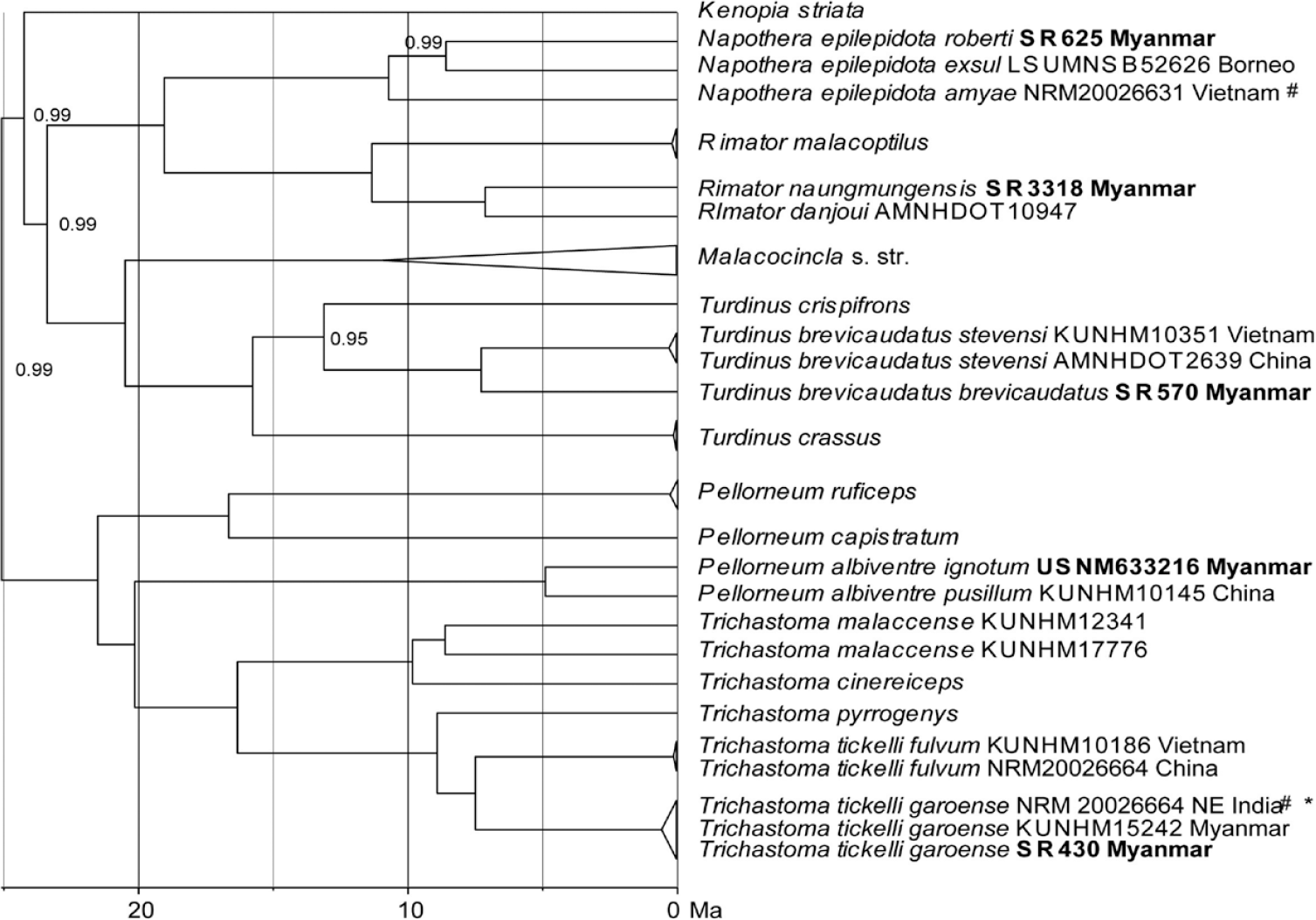

In Pellorneidae, we found remarkable intraspecific diversification in four species that appeared as deep splits in the multi-locus tree (Figure 5; the total data set comprised 94 individual sequences of 52 species). Several genotyped individuals identified as the Spot-throated Babbler Pellorneum albiventre in the field turned out to be individuals of the Buff-breasted Babbler Trichastoma tickelli. In our sampling, we could identify a single sample of P. albiventre from Naung Mung (USNM633216) that differed from a Chinese sample of that same species (Guangxi) by a p-distance of 4% (Table 2; Figure 5). The local Myanmar population of the Buff-breasted Babbler belongs to subspecies T. t. garoense whose range extends westward to the Eastern Himalayas. Accordingly, samples from Hkakabo Razi formed a clade (haplotype cluster) with samples from north-east India and these were separated from a second clade (cluster) including populations from adjacent Vietnam and southern China (subspecies T. t. fulvum) by 26 substitutions (equalling a p-distance of 5.5%; Table 2; Figures 4B, 5). Further intraspecific differentiation was found in the Puff-throated Babbler Pellorneum ruficeps: The local subspecies P. r. pectorale from the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar appeared as one of four deeply separated clades with closest relatives in the Himalayas (ssp. mandelli) and in the Western Ghats (ssp. olivaceum; Figure 4D; p-distances of 3.1–3.2%; Table 2). Chinese and Thai populations of the Puff-throated babbler were greatly divergent from the three other clades with p-distances of 5.0–6.2% (Table 2).

Figure 5. Multi-locus phylogeny of Pellorneidae based on 4009 bp concatenated sequence data of cytochrome-b (1134 bp), ND2 (1041bp) fib5 (586 bp), MUSK (638 bp) and TGFB2 (610 bp); our data set and that of Moyle et al. (Reference Moyle, Andersen, Oliveros, Steinheimer and Reddy2012) (total data set: 94 concatenated sequences of 52 species), subclade of their clade B shown; Bayesian inference of phylogeny, MCMC chain length 30,000,000 generations, node support from posterior probabilities shown; our samples from Hkakabo Razi in bold print; # denotes GenBank sequences from Price et al. (Reference Price, Hooper, Buchanan, Johansson, Tietze, Alström, Olsson, Ghosh-Harihar, Ishtiaq, Gupta, Martens, Harr, Singh and Mohan2014); * = in the original study the specimen had been misidentified as Pellorneum albiventre.

Moreover, intraspecific splits were found between Streaked Wren-babbler Turdinus brevicaudatus from Hkakabo Razi (Figure 5) and adjacent populations from Vietnam and southern China as well as between Eyebrowed Wren-babbler Napothera epilepidota from Hkakabo Razi, Vietnam and Borneo (three different lineages; Figure 5). Finally, the greatest intraspecific p-distance of nearly 10% was found between the local population of the Rufous-throated Fulvetta Schoeniparus rufogularis collaris from our study site and adjacent populations from Vietnam (A. r. kelleyi; Table 2, Figs 4C, 5).

Leaf warblers (Phylloscopidae)

For a control of correct species identification, we genotyped all samples of Golden-spectacled Warbler. In the field, these were tentatively identified as either Grey-crowned Warbler Phylloscopus tephrocephalus, Green-crowned Warbler P. burkii or Whistler’s Warbler P. whistleri. Contrary to our field species lists, all samples are Bianchi’s Warbler Phylloscopus valentini. The White-spectacled Warbler Phylloscopus intermedius is also present in the area; however, some specimens were misidentified as P. valentini (for difficulties of species identification, see Discussion). In the haplotype network inferred from a larger sequence set (n = 41) the local population at Hkakabo Razi appeared as genetically distinct from the nominate form P. v. valentini from south-western China and subspecies P. v. latouchei from southern and south-eastern China (Figure 6). Phylogeographic structure in the Grey-cheeked Warbler Phylloscopus poliogenys was less clear, because sequences from Myanmar formed a complex network with samples from southern China and Vietnam and the whole cluster was separated from a sample from the Himalayas (Arunachal Pradesh, India) by a minimum of 24 substitutions (Figure 6). Intraspecific genetic distances in the two leaf warbler species ranged from 1.3 to 4% (Table 2). Furthermore, all samples that were tentatively assigned to the Mountain Warbler Phylloscopus trivirgatus turned out to be Yellow-throated Fulvetta Schoeniparus cinereus.

Figure 6. Phylogeographic structure in two Sino-himalayan leaf-warbler species, haplotype networks based on mitochondrial cytochrome-b; A) Phylloscopus poliogenys, B) Phylloscopus valentini (n = 41; 595 bp).

Bush warblers (Scotocercidae)

This group attracted our attention when we captured some aberrant individuals of a small warbler species that was preliminarily determined as Yellow-bellied Warbler Abroscopus superciliaris – a species that has not been previously recorded at Hkakabo Razi. However, this local form differed from the nominate form that breeds in eastern and southern Myanmar (and from other subspecies throughout the species’ range) by its rather large body size and by a large bright-white belly patch (Figure 7). We tentatively assigned the Hkakabo Razi population to subspecies A. s. drasticus that breeds in north-eastern India (Assam) and northern Myanmar. Local samples from our study site differed from nominate subspecies A. s. superciliaris from eastern Myanmar by a p-distance of 4.4% (Table 2). Intraspecific differentiation of a similar magnitude was found between local samples of the Rufous-faced Warbler Abroscopus albogularis albogularis and samples from southern China and Taiwan (subspecies A. a. fulvifacies; Table 2, Figure 7). Within the Black-faced Warbler A. schisticeps one sequence differed from a clade of subspecies A. s. ripponi from China by a p-distance of 1.6%. However, that sample was taken from a captive individual of unknown origin, so we cannot infer any information on a putative phylogeographic pattern from this shallow split.

Figure 7. Multi-locus phylogeny of bush warblers (Scotocercidae) based on 2399 bp concatenated sequence data of cytochrome-b (1036 bp), myoglobin intron 2 (683 bp) and ODC intron 6 (680 bp); our data set and that of Alström et al. (Reference Alström, Hohna, Gelang, Ericson and Olsson2011), subsample of their basal clades including our target species; Bayesian inference of phylogeny, MCMC chain length 30,000,000 generations, node support from posterior probabilities shown; our samples from Hkakabo Razi in bold print.

Furthermore, the local population of the Chestnut-headed Tesia Cettia castaneocoronata belonged to the same genetic lineage as samples from the Himalayas (Arunachal Pradesh, India). The multi-locus tree shows a deep split between this Himalaya-Myanmar lineage and a sample from neighbouring China that equalled a p-distance of 7.8% (Table 2, Figure 7; for the problematic subspecific taxonomy see discussion). That divergence level was similar to between-clade distances among four closely related tesia species (Figure 7; 6.1–7.2%).

Cupwings, Pnoepygidae

So far, only the Pygmy Cupwing Pnoepyga pusilla is confirmed for Hkakabo Razi. However, Scaly-breasted Cupwing P. albiventer is present at other localities in central and northern Myanmar and represents a separate genetic lineage. The Myanmar populations differ from P. a. albiventer and P. a. pallidior in the Himalayas, and also from Chinese P. a. mutica by genetic p-distances of about 4.0% (Table 2).

Discussion

Species concepts and species limits

Species inventories of living organisms are the basics of all conservation effort. The combined use of different independent analytical approaches for species diagnosis (using phenotypical and bioacoustic traits as well as molecular markers) including their taxonomy and systematic classification has recently been discussed under the flagship term ’integrative taxonomy’ (Padial et al. Reference Padial, Miralles, De la Riva and Vences2010, Schlick-Steiner et al. Reference Schlick-Steiner, Steiner, Seifert, Stauffer, Christian and Crozier2010). This multi-dimensional approach has been applied to a number of South-East Asian and Indomalayan bird species (Irestedt et al. Reference Irestedt, Fabre, Batalha-Filho, Jonsson, Roselaar, Sangster and Ericson2013, Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Sun, Fischer, Tietze and Martens2014) some of them new to science (Alström et al. Reference Alström, Xia, Rasmussen, Olsson, Dai, Zhao, Leader, Carey, Dong, Cai, Holt, Manh, Song, Liu, Zhang and Lei2015, Reference Alström, Rasmussen, Zhao, Xu, Dalvi, Cai, Guan, Zhang, Kalyakin, Lei and Olsson2016) including a re-evaluation of the species status of the endemic Rimator naungmungensis from northern Myanmar (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Kyaw, Milensky and Päckert2018).

In contrast to integrative taxonomy, the value of genetic sequence data, in particular that of mitochondrial DNA as a sole indicator of species limits, is restricted (Dávalos and Russell Reference Dávalos and Russell2014, Mutanen et al. Reference Mutanen, Kivela, Vos, Doorenweerd, Ratnasingham, Hausmann, Huemer, Dinca, van Nieukerken, Lopez-Vaamonde, Vila, Aarvik, Decaens, Efetov, Hebert, Johnsen, Karsholt, Pentinsaari, Rougerie, Segerer, Tarmann, Zahiri and Godfray2016, Yu et al. Reference Yu, Rao, Matsui and Yang2017). Any taxonomic recommendation inferred from phylogenies will inevitably rely on two criteria of the phylogenetic species concept, i.e. diagnosability and reciprocal monophyly (Sangster Reference Sangster2009, Reference Sangster2014). Distance-based approaches using genetic distances as a threshold can be a useful tool for detection of intraspecific diversification (Tavares and Baker Reference Tavares and Baker2008, Aliabadian et al. Reference Aliabadian, Kaboli, Nijman and Vences2009, Johnsen et al. Reference Johnsen, Rindal, Ericson, Zuccon, Kerr, Stoeckle and Lifjeld2010, Bergmann et al. Reference Bergmann, Rach, Damm, DeSalle, Schierwater and Hadrys2013), however their general application for species delimitation remains problematic (Moritz and Cicero Reference Moritz and Cicero2004, del Hoyo et al. Reference del Hoyo, Collar, Christie, Elliot and Fishpool2014: Figure 12). Typically, good songbird species pairs differ by genetic distances higher than 3% (Dietzen et al. Reference Dietzen, Witt and Wink2003) but this can only be regarded as an approximate value. Many sister species of birds differ by genetic distances lower than 2% (Johns and Avise Reference Johns and Avise1998), e.g. in bulbuls (Light-vented Bulbul Pycnonotus sinensis and Styan’s Bulbul P. taiwanus; Dejtaradol et al. Reference Dejtaradol, Renner, Karapan, Bates, Moyle and Päckert2016) and in leaf-warblers (Chestnut-crowned Warbler Phylloscopus castaniceps and Javan Warbler P. grammiceps; Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Martens, Sun and Veith2004). The practical use of a mere DNA-based taxonomy is even more limited in the case of cryptic species pairs that despite high genetic distances lack distinctive phenotypical or behavioural distinctiveness, such as in some leaf warblers (e.g. P. affinis/P. occisinensis; Martens et al. Reference Martens, Sun and Päckert2008). Thus, a genetic survey including the identification of previously unknown genetic lineages from a study region can only be the first step towards a choice of candidate species for more comprehensive follow-up studies based on a broad sampling and analysis of multiple traits.

Additions or corrections to species lists

Cryptic species (lacking clear phenotypic diagnosability against congeners) can be rather difficult to identify in the field, in particular females or juveniles. Based on our genetic analyses, some misidentifications were detected in our sample lists that likely apply to previously published species lists for the study site (Rappole et al. Reference Rappole, Renner, Shwe and Sweet2005, Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015, Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Kyaw, Li, Zhao, Zeng, Swa and Quan2017). Our genetic analysis identified two species that have not been previously recorded at Hkakabo Razi: the Yellow-bellied Warbler Abroscopus superciliaris and Bianchi’s Warbler Phylloscopus valentini. So far, the latter seems to be the only species of the golden-spectacled warbler complex at the study site, because the presence of P. tephrocephalus, P. whistleri and P. burkii (previously listed by Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015) could not be confirmed by our genetic analysis.

It is very likely the Grey-cheeked Fulvetta Alcippe morrisonia does not occur at our study site, because all individuals in our large sampling set turned out to be a genetically distinct lineage of the Nepal Fulvetta A. nipalensis. In fact, the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar are located near the far north-western border of the wide breeding range of A. morrisonia, thus the species might just not be native to Hkakabo Razi.

Taxonomic confusion

As zoological taxonomy and systematics are in steady flux, nomenclatorial changes can have an impact on species lists (Hazevoet Reference Hazevoet1996, Isaac et al. Reference Isaac, Mallet and Mace2004, Knapp et al. Reference Knapp, Lughadha and Paton2005, Padial et al. Reference Padial, Miralles, De la Riva and Vences2010). In the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar, scimitar-babblers of the genus Pomatorhinus are a striking example. Pomatorhinus ferruginosus is listed as one of two species occurring at Hkakabo Razi (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015). This classification is in accordance with Gill and Donsker (Reference Gill and Donsker2019) who do not distinguish P. phayrei at the species level but subsumed all subspecific taxa under P. ferruginosus s.l. (compare Figure 3). In contrast, Reddy and Moyle (Reference Reddy and Moyle2011) restricted the range of P. ferruginosus to the Eastern Himalayas of Nepal, Bhutan and India and distinguished populations of Northern Myanmar as one of five diagnosable species-level taxa (P. stanfordi in Myanmar; Figure 3) (Collar and Inskipp Reference Collar and Inskipp2012, Nyári and Reddy Reference Nyári and Reddy2013). For a lack of genetic distinctiveness, Reddy and Moyle (Reference Reddy and Moyle2011) furthermore synonymized the form phayrei from the northern Chin Hills with P. formosus from Assam. According to current taxonomy in the "Handbook of the Birds of the World" and BirdLife International, P. ferruginosus would be the incorrect taxon name for Hkakabo Razi, because the nominate Himalayan form is treated as a separate species and all other taxa are subsumed under P. phayrei (Brown-crowned Scimitar-babbler; del Hoyo and Collar Reference del Hoyo and Collar2016). This striking example shows that three different species-level taxon names can be applied to the same genetic lineage of scimitar babblers from Hkakabo Razi depending on the taxonomic authority referred to (Figure 3).

For other Pomatorhinus species, previously recommended taxonomic changes have not yet been accepted by any taxonomic authority despite strong evidence of species-level polyphyly from phylogenetic data, such as in the White-browed Scimitar-babbler P. schisticeps (Figure S1; Moyle et al. (Reference Moyle, Andersen, Oliveros, Steinheimer and Reddy2012). In a phylogenetic study by Reddy and Moyle (Reference Reddy and Moyle2011) nine out of 12 subspecies currently distinguished by del Hoyo and Collar (Reference del Hoyo and Collar2016) grouped as three distinct clades with one of them firmly nested in the Streak-breasted Scimitar-babbler P. ruficollis. This grouping received further support from a phylogeographic study by Dong et al. (Reference Dong, Li, Zou, Lei, Liang, Yang and Yang2014) who recommended a transfer of five taxa from the olivaceus group (including three subspecies that occur in Myanmar) from P. schisticeps to P. ruficollis (Inskipp et al. Reference Inskipp, Collar and Pilgrim2010). Though most taxonomic authorities have not followed this recommendation yet (del Hoyo and Collar Reference del Hoyo and Collar2016, Gill and Donsker Reference Gill and Donsker2019), any future taxonomic rearrangement will certainly affect species lists for Myanmar.

Cryptic diversity and its relevance for conservation strategies

A recent study on global avian biodiversity estimated the total number of bird species to be twice as high as the currently accepted 9,000 to 10,000 species-level taxa (Barrowclough et al. Reference Barrowclough, Cracraft, Klicka and Zink2016). However, these high numbers did not result from scientific descriptions of potentially new species but from genetically distinctive subspecies that might deserve full species status. Opponents of this approach reasoned that the putative increase in mammal and bird species numbers is mainly due to oversplitting and taxonomic inflation because of a growing popularity of the phylogenetic species concept over the biospecies concept (Isaac et al. Reference Isaac, Mallet and Mace2004, Zachos Reference Zachos2013, Zachos et al. Reference Zachos, Apollonio, Bärmann, Festa-Bianchet, Göhlich, Habel, Haring, Kruckenhauser, Lovari and McDevitt2013). This critique has been greatly challenged by an empirical revision of more than 700 taxonomic papers over almost six decades (Sangster Reference Sangster2009). His conclusion was that the recent increase of accepted bird species numbers is based on robust taxonomic progress using an integrative taxonomic approach that combined results from phenotypic, genetic, ecological and bioacoustic analyses. This statement is important for our study because in case of cryptic phenotypical variation the assessment of genetic diversity can be the first step towards the definition of distinctiveness and diagnosability of a given taxon. In fact, the greatest part of cryptic genetic lineages discovered from our data set could already be assigned to a named taxon, i.e. to a valid subspecies in most cases. Thus, given the support from further morphological and bioacoustic analyses (as in the case of Rimator naungmungensis; Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Kyaw, Milensky and Päckert2018) our results could justify up-ranking of 13 subspecies that are at least partly endemic to the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar to full species-level taxa.

Furthermore, it has often been stated that conservation strategies might also consider subspecies particularly when they are endemic for the region under protection (Phillimore and Owens Reference Phillimore and Owens2006). As taxonomy and systematics are in steady flux and some of the global bird species lists are updated even annually, opinions on taxonomic rank of endemics might change over time. The Naung Mung Wren-babbler is a good example. Described as a species, some authors have argued against its species status for a long time (Collar and Pilgrim Reference Collar and Pilgrim2007, Collar Reference Collar2011), until that species-level split was finally recognized in the recent Illustrated Checklist of Birds of the World (del Hoyo and Collar Reference del Hoyo and Collar2016). This decision was taken without knowing the strongest argument for this split, i.e. the strikingly high genetic distances of almost 10% between Rimator naungmungensis and R. danjoui (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Kyaw, Milensky and Päckert2018). Because recognition of species-level taxa predominantly depends on the species concept and the criteria of species delimitation applied (Sangster Reference Sangster2009), local and regional species richness and the number of endemics are also affected by these conceptual aspects (Peterson and Navarro-Sigüenza Reference Peterson and Navarro-Sigüenza1999). For instance, in some cases lumping of many taxa into a single widely distributed polytypic species has promoted extinction of island endemics of the Macaronesian archipelago (Hazevoet Reference Hazevoet1996).

Others have argued against a prominent role of subspecies for conservation policies because the greater part of distinct genetic lineages within species would not represent single subspecies but previously unnamed taxonomic units (Zink Reference Zink2004). Thus, conservation strategies should rather focus on these unnamed lineages. There are possible solutions for confronting and solving this problem. Because scientific descriptions of new taxa are a complicated and time-consuming work many scientists have argued in favour of an accelerated taxonomy using "operational taxonomic units" (OTU) to speed up the global biodiversity assessment (Costello et al. Reference Costello, May and Stork2013, He et al. Reference He, Wan, Koepfli, Jin, Liu and Jiang2017). For populations that have not been given a scientific name yet, others have introduced the term of the "evolutionary significant unit" (ESU) (Ryder Reference Ryder1986, Moritz Reference Moritz1994). This term is frequently applied to genetically distinct populations at a low distance level whose taxonomic status is still under debate. In our dataset, we also found some examples of genetic splits within one subspecific taxon, e.g. in Phylloscopus valentini valentini, Phylloscopus poliogenys poliogenys, Alcippe nipalensis nipalensis and Pnoepyga albiventer albiventer (Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Martens, Liang, Hsu and Sun2013). These genetically distinct populations might either be treated as ESUs or as "unconfirmed candidate species" (UCS) (Padial et al. Reference Padial, Miralles, De la Riva and Vences2010). ESU or USC are working hypotheses or placeholders for future taxonomic work (fast track taxonomy) (Riedel et al. Reference Riedel, Sagata, Suhardjono, Tänzler and Balke2013). If genetic distinctiveness of local populations is documented and substantiated by further data, either i) a new taxon can be described in the near future or ii) scientific names available but not in use can be re-established for locally or regionally endemic forms, such as for Chinese buff-barred warblers, Phylloscopus pulcher vegetus (Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Sun, Fischer, Tietze and Martens2014).

Conclusion

Cryptic avian diversity in the Hkakabo Razi Landscape of northern Myanmar covers all levels of genetic divergence and taxonomic rank. Our study groups included subspecies that might merit species rank due to genetic (and partly morphological) distinctiveness as well as intraspecific ESUs that might justify improved conservation efforts. These findings highlight the outstanding bird species richness of the pristine forests at Hkakabo Razi. With a surface area of more than 1,000,000 ha and an elevational gradient from 400 to 5,888 m the tentative World Heritage Site of Hkakabo Razi harbours a great diversity of forest and high alpine ecotones that are home to a remarkable faunal species richness (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Milensky, Aung, Shwe and Aung2015, Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Kyaw, Li, Zhao, Zeng, Swa and Quan2017). It should be emphasised that the genetic results are preliminary and were achieved in a pilot study over a narrow period. Therefore, our assessment of avian biodiversity only scratches the surface and detection of more cryptic genetic lineages can be expected from broader future studies. Moreover, our sampling was biased towards understorey tropical species assemblages of the lower to medium elevations. A more pronounced phylogeographic structure can generally be expected from those species occupying sky island habitats of the upper mountain belt and the mountain summits: birds (McCormack et al. Reference McCormack, Bowen and Smith2008, Robin et al. Reference Robin, Vishnudas, Gupta and Ramakrishnan2015, Purushotham and Robin Reference Purushotham and Robin2016); mammals: He et al. (Reference He, Wan, Koepfli, Jin, Liu and Jiang2017). Leaf warbler species of the high-elevation forest belt are typical examples, e.g. Bianchi’s Warbler (Phylloscopus valentini; our study) or Blyth’s Warbler, Phylloscopus reguloides with ssp. assamensis as a distinctive genetic lineage from north-eat India and Myanmar (Olsson et al. Reference Olsson, Alström, Ericson and Sundberg2005, Päckert et al. Reference Päckert, Blume, Sun, Wei and Martens2009). The outstanding value for biodiversity research of the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar is furthermore highlighted by several recent descriptions of plant species new to science from that region (Zhou and Chen Reference Zhou and Chen2005). Several new vertebrate species have also been recently described from this region, e.g. bats (Soisook et al. Reference Soisook, Thaw, Kyaw, Lin Oo, Awatsaya, Suarez-Rubio and Renner2017). Even in primates a new species of snub-nosed monkey has been recently described from the mountain ranges of north-eastern Kachin State near the border with China (Geissmann et al. Reference Geissmann, Grindley, Momberg, Lwin, Aung and Aung2009). Most of these newly described species from northern Myanmar are presumably rare endemics with a narrow distribution range and are thus generally threatened by any kind of anthropogenic impact. During the last 15 years, severe forest decline has been documented in many parts of Myanmar including large areas of forests in the north, including our study region (Renner et al. Reference Renner, Rappole, Leimgruber and Kelly2007, Bhagwat et al. Reference Bhagwat, Hess, Horning, Khaing, Thein, Aung, Aung, Phyo, Tun and Oo2017). Yet even in the north, tree cover of forested areas of the Hukaung Valley has decreased by a mean of 1.7% in a study period of five years and an additional 0.6% in the following five years with highest losses at lower elevations (Papworth et al. Reference Papworth, Rao, Oo, Latt, Tizard, Pienkowski and Carrasco2017). Increased conservation efforts are advisable to prevent future biodiversity losses, including loss of genetic diversity and so far undescribed species, in the Northern Mountain Forests of Myanmar. We certainly expect that future intensive field surveys across elevational gradients flanked by genetic monitoring of local populations will uncover more examples of cryptic faunal and floral diversity of the Hkakabo Razi Region.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270919000273

Acknowledgements

This study was initiated and funded by UNESCO Bangkok under contract number 4500306550, for the genetic study and 4500291033 for fieldwork. The National Geographic Society provided funding for the 2013/14 trip by S. C. R. (GEFNE48-12). We cordially thank Vanessa Achilles, Angsana Chuamthaisong, and Koen Meyers for constant support during the project. We are grateful to Aung Kyaw (Yangon), Pipat Soisook (Hat Yai), San Sein Oo (Nay Pyi Daw), Sang Nai Dee (Putao), and Uraiporn Pimsai (Hat Yai) for help during the field trips. We also cordially thank Townsend A. Peterson (University of Kansas, KU Biodiversity Institute, USA) and Arpad Nyari (University of Tennessee, USA) for providing unpublished cytochrome-b sequence data of spectacled warbler species (Phylloscopus valentini and P. poliogenys) for comparison. We are most grateful to Director General Hla Maung Thein from MONREC for facilitating the genetic research under the regulations of the Nagoya Protocol (document NR-2/2-2017). J.M. was regularly sponsored for field work in Asia by Feldbausch Foundation and Wagner Foundation at Fachbereich Biologie of Mainz University. We thank anonymous reviewers for their comments, which helped to improve the manuscript.