Introduction

Waterbirds have been used as indicators of changes in the environment for years (Amano et al. Reference Amano, Székely, Sandel, Nagy, Mundkur, Langendoen, Blanco, Soykan and Sutherland2017). Regular monitoring of waterbirds enables the rapid perception of changes in ecosystems (Wetlands International 2010). Based on such monitoring, we now know that entire ecological groups, such as benthivorous diving ducks throughout the northern hemisphere, are declining dramatically (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Afton, Anderson, Clark, Custer, Lawrence, Pollard and Ringelman2000, Aunins et al. Reference Aunins, Nilsson, Hario, Garthe, Dagys and Pedersen2013, Nagy et al. Reference Nagy, Flink and Langendoen2014). The reasons for this are unknown, but different factors are being considered, such as contamination of food resources (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Afton, Anderson, Clark, Custer, Lawrence, Pollard and Ringelman2000, Hobson et al. Reference Hobson, Wunder, Van Wilgenburg, Clark and Wassenaar2009), hunting (Afton and Anderson Reference Afton and Anderson2001), fishery bycatch, human disturbance, and habitat loss (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Perennou and Lutz2009).

Bycatch in fishing nets of unintentional species is a well-known phenomenon worldwide (Baum et al. Reference Baum, Myers, Kehler, Worm, Harley and Doherty2003, Lewison et al. Reference Lewison, Crowder, Read and Freeman2004, Pott and Wiedenfeld Reference Pott and Wiedenfeld2017). Many animal species are subject to the pressure of gillnet fishing activities, and their abundance is decreasing as a result of bycatch (Small et al. Reference Small, Waugh and Phillips2013). Along with many other types of human-induced mortality, it poses a major threat to diving waterbirds (Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Small and French2013, Pott and Wiedenfeld Reference Pott and Wiedenfeld2017). The number of birds annually perishing in bycatch in the North and Baltic Seas has been estimated at 100,000–200,000, with most of these occurring in the Baltic Sea (Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister and Stipniece2009). In the context of the bycatch impact on bird populations, it is important to identify particularly vulnerable species or populations as well as key areas and seasons in which bycatch may be occurring (Small et al. Reference Small, Waugh and Phillips2013). Greater Scaup Aythya marila, along with Common Pochard Aythya ferina and Steller’s Eider Polysticta stelleri, have the highest rate of long-term decline in abundance among Western Palearctic diving waterbirds (Nagy et al. Reference Nagy, Flink and Langendoen2014). The present work aims to highlight what could be the key factor responsible for the decrease in a whole population of a particular benthivorous species.

The southern Baltic, one of the most important wintering sites for diving waterbirds anywhere in the Palearctic (Durinck et al. Reference Durinck, Skov, Jensen and Pihl1996), is becoming increasingly attractive to Greater Scaup as a consequence of the shift in its wintering range farther to the east and north (Marchowski et al. Reference Marchowski, Jankowiak, Wysocki, Ławicki and Girjatowicz2017). During the non-breeding period, Greater Scaup prefer to congregate in large flocks (Marchowski et al. Reference Marchowski, Neubauer, Ławicki, Woźniczka, Wysocki, Guentzel and Jarzemski2015, Marchowski and Leitner Reference Marchowski and Leitner2019), so nearly the whole flyway population can occupy just a few attractive sites (van Erden and de Leeuw Reference van Erden, de Leeuw, van der Velde, Rajagopal and bij de Vaate2010). In the Western Palearctic, these places include the Odra River Estuary in Poland and Germany, eastern coastal areas of Germany like Wismar Bay and Traveförde (Skov et al. Reference Skov, Heinänen, Žydelis, Bellebaum, Bzoma, Dagys, Durinck, Garthe, Grishanov, Hario, Kieckbusch, Kube, Kuresoo, Lasson, Luigujoe, Meissner, Nehls, Nilsson, Petersen, Roos, Pihl, Sonntag, Stock, Stipniece and Wahl2011), as well as Lake Ijsselmeer and nearby areas in the Netherlands (van Erden and de Leeuw Reference van Erden, de Leeuw, van der Velde, Rajagopal and bij de Vaate2010).

In the southern Baltic during the same time of year (October-April) and in the same areas (shallow coastal waters) two phenomena overlap: a large concentration of gillnet fishery and a large concentration of foraging diving birds (Stempniewicz Reference Stempniewicz1994, Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012). As a consequence, bird bycatch is larger there than in deeper sea waters (Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012), where fishing nets are more widely dispersed. The ongoing shift in the wintering range of waterbirds in response to global warming (Musil et al. Reference Musil, Musilová, Fuchs and Poláková2011, Lehikoinen et al. Reference Lehikoinen, Jaatinen, Vahatalo, Preben, Crowe, Deceuninck, Hearn, Holt, Hornman, Keller, Nilsson, Langendoen, Tomankova, Wahl and Fox2013, Pavon-Jordan et al. Reference Pavon-Jordan, Fox, Dagys, Deceuninck, Devos, Hearn, R, Holt, Hornman, Keller, Langendoen, Ławicki, Lorentsen, Luiguj, Meissner, Musil, Nilsson, Paquet, Stipniece, Stroud, Wahl, Zenatello and Lehikoinen2015) is also evident in the Odra River Estuary, where the shorter period of ice coverage means that this area is increasing in importance for benthivorous ducks (Marchowski et al. Reference Marchowski, Jankowiak, Wysocki, Ławicki and Girjatowicz2017).

There are three main aims of this work. First, we have attempted to determine whether bycatch is having a significant impact on the reduction in Greater Scaup numbers from populations wintering in north-west Europe. To test this, we used recently available bycatch data relating to this species from the area occupied by its population (Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister and Stipniece2009, Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012, van den Boogaard et al. Reference van den Boogaard, Krijgsveld, van Rijn and Boudewijn2013, Petersen and Nielsen Reference Petersen and Nielsen2015, Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017) and computed the Potential Biological Removal (PBR) value, which indicates how many individuals can be ‘harvested’ from a populations without its overall vitality being compromised (Dillingham and Fletcher Reference Dillingham and Fletcher2008). The International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) advises that PBR can be applied as the primary metric for determining whether a seabird bycatch problem exists (ICES 2013). This method requires just a few population parameters, like the age of first breeding, adult survival and population size (Dillingham and Fletcher Reference Dillingham and Fletcher2008).

Second, we aimed to model the population change according to age-structured matrix models (ASMM). The use of PBR for analyses of the magnitude of a safe bird ‘harvest’ has been debated recently. As the simplicity of PBR exposes it to large fluctuations in value, the subjective use of model parameters can lead to false applications (O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Cook and Robinson2017). To test the legitimacy of using PBR, we applied the values obtained with this model to a stable and declining populations and we made simulations using ASMM. As a result, we were able to trace what the trajectory of the population would look like over a period of 30 years and to assess whether the calculated PBR will not in fact harm the viability of the population. We also applied the estimated bycatch values to the ASMM, in order to see how additional mortality might affect a stable and declining populations over a period of 30 years.

Third, we give a formula for calculating the mortality of birds in fishing nets in the absence of annual monitoring. There is some literature on a related topic, but it is more focused on assessing the potential risk of bycatch based on the identification of overlapping areas for bird occurrences and fishing activities (e.g. Sonntag et al. Reference Sonntag, Schwemmer, Fock, Bellebaum and Garthe2012, Bradbury et al. Reference Bradbury, Shackshaft, Scott-Hayward, Rextad, Miller and Edwards2017). This approach does not specify the estimated bycatch size but defines vulnerability to bycatch and bycatch risk (ICES 2018). In our work we go further, knowing the vulnerability to bycatch and the area of bycatch risk, we can also, under certain assumptions, estimate the number of harvested birds. We developed a simple model to propose a long-term bycatch monitoring strategy without the need for costly annual monitoring.

Methods

Study area

The Greater Scaup is mainly migratory; two subspecies are recognised: A. m. marila, breeding in northern Eurasia, and A. m. nearctica, breeding in north-east Siberia and North America (Carboneras and Kirwan Reference Carboneras, Kirwan, del Hoyo, Elliott, Sargatal, Christie and de Juana2017). Within the marila subspecies there are two populations, one wintering in the Black and Caspian Sea basins and the other wintering in north-west Europe (Wetlands International 2018). Our calculations concern the population wintering in north-west Europe, treated as a separate conservation unit, the so-called biogeographical or flyway population. Ninety-five percent of this population breeds in northern and north-eastern Europe, mainly in Russia, with the remainder around Iceland, Norway, Finland and Estonia (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Perennou and Lutz2009). The main breeding area of this population in Russia is the Pechora River Basin (Viksne et al. Reference Viksne, Svazas, Czajkowski, Janus, Mischenko, Kozulin, Kuresoo and Serebryakov2010). Birds from this breeding range overwinter principally in the eastern North Sea and western Baltic Sea. The key areas where most of this population spends the winter (~90%) are the coastal waters of the Netherlands, Germany, Poland, Sweden, Denmark and the UK (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Perennou and Lutz2009, van Erden and de Leeuw Reference van Erden, de Leeuw, van der Velde, Rajagopal and bij de Vaate2010, Skov et al. Reference Skov, Heinänen, Žydelis, Bellebaum, Bzoma, Dagys, Durinck, Garthe, Grishanov, Hario, Kieckbusch, Kube, Kuresoo, Lasson, Luigujoe, Meissner, Nehls, Nilsson, Petersen, Roos, Pihl, Sonntag, Stock, Stipniece and Wahl2011).

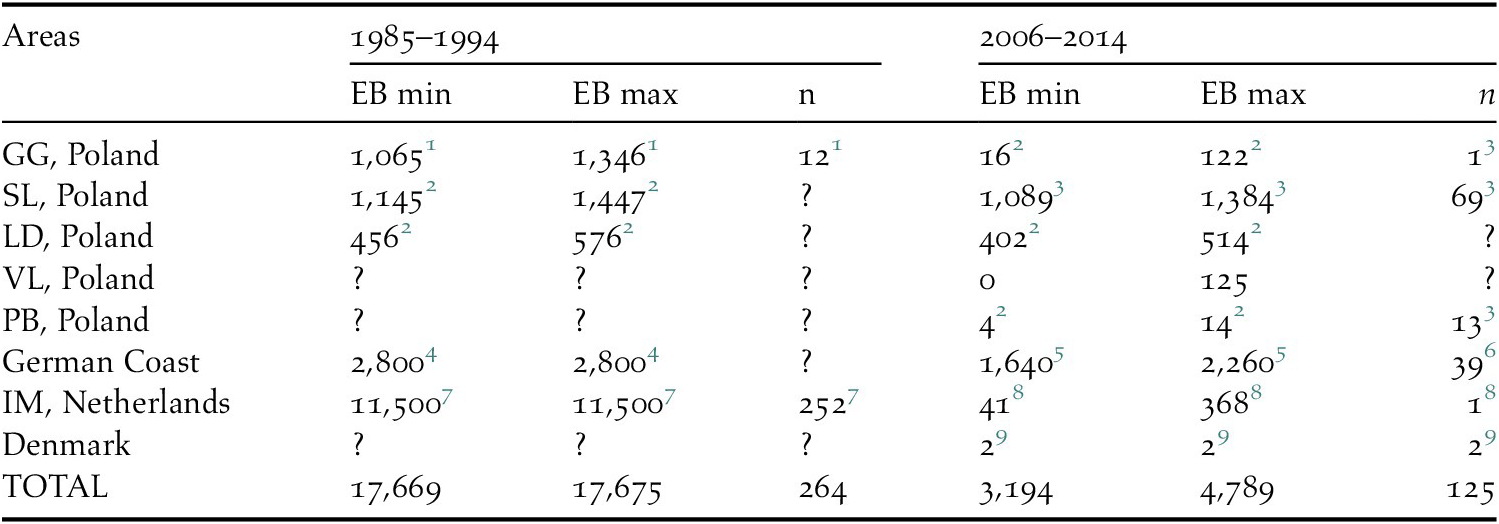

Bird bycatch

We used the latest published information to determine the level of bird bycatch from the target population. Although studies of Greater Scaup bycatch have been geographically local, they have covered most of the important wintering areas (Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister and Stipniece2009, Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012, van den Boogaard et al. Reference van den Boogaard, Krijgsveld, van Rijn and Boudewijn2013, Petersen and Nielsen Reference Petersen and Nielsen2015, Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017). Therefore, as there are gaps in the coverage of the study area, the values calculated in this paper should be treated as minimal values. Recent bycatch data are available from Poland: the Odra River Estuary, Pomeranian Bay and the Gulf of Gdańsk (Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017). Data from the Odra Estuary were computed, and the annual bycatch rate estimated, by Psuty et al. (Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017). The bycatch data from the other two Polish sites were not extrapolated to all areas of those basins because the samples were too small. Raw data regarding the number of birds caught in the Pomeranian Bay and Gulf of Gdańsk were calculated using parameters such as their proportion in the bycatch and the numbers of birds present in the bycatch compared to their abundance in that basin or areas nearby. We also use this same approach to estimate bycatch in two other important sites for Greater Scaup in Poland: Lake Dąbie and the Vistula Lagoon (for details see: Bycatch estimation method for limited data, below). Data from Germany come from 2006–2009: a total of 352 birds were affected, and the proportion of Greater Scaup in the bycatch was 11% (Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister and Stipniece2009). The annual average number of birds bycaught during this period off the eastern part of the German Baltic coast was 17,551 (range 14,905–20,533) between November and May (Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012). On this basis, we can estimate the number of bycaught Scaup as being in the 1,640–2,260 range. We also analysed recent data from the Dutch Lakes IJsselmeer and Markermeer (van den Boogaard et al. Reference van den Boogaard, Krijgsveld, van Rijn and Boudewijn2013) and from Danish coastal waters (Petersen and Nielsen, Reference Petersen and Nielsen2015). There is no information that any significant numbers of Greater Scaup are bycaught off UK coasts; Article 12, reporting under the Birds Directive in 2013, did not mention this as pressure on or even a threat to this species in the UK. In recent years, Greater Scaup bycatch in another important wintering site – the Lough Neagh System – was not deemed a threat to this species (Allen et al. Reference Allen, Mellon and Enlander2004). No information regarding bycatch is available from other countries where Greater Scaup overwinter and stage during migration (e.g. the Kaliningrad region of Russia, Sweden, Lithuania, Latvia or Estonia). We compare two periods, i.e. the new numbers described above and the old numbers available for the 1980s and early 1990s from the Gulf of Gdańsk (Stempniewicz Reference Stempniewicz1994), the German coast (Grimm Reference Grimm1985) and the Dutch Lakes IJsselmeer and Markermeer (van Erden et al. Reference van Erden, Dubbeldam and Muller1999), in order to assess changes in the extent of bycatch over time.

The study by Psuty et al. (Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017) indicates that 137 carcasses of all waterbirds were found in fishing nets in the Odra River Estuary in 2014/15; 69 were Greater Scaup (50.4%). Combined with fishing net effort data, this figure enabled the bycatch to be estimated for two seasons: 2,487 individual diving birds in 2013/14 and 2,930 in 2014/15; the respective figures for Greater Scaup are 1,089 (2013/14) and 1,384 (2014/15), giving a mean of 1,237 (Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017). Off the German coast a mean number of 1,940 Greater Scaup (1,640–2,260) are bycaught each year (Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister and Stipniece2009, Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012). The most recent data from the Dutch Lakes IJsselmeer and Markermeer give a bycatch in the range of 41–368 (van den Boogaard et al. Reference van den Boogaard, Krijgsveld, van Rijn and Boudewijn2013). During a study of bycatch in Denmark in 2015, there were two accidental captures of Greater Scaup in fishing nets (Petersen and Nielsen Reference Petersen and Nielsen2015).

Population size estimate

For the Northern Europe/Western Europe Greater Scaup population, Wetlands International (2018) still returns the old estimate of 310,000 after Laursen et al. (Reference Laursen, Pihl and Komdeur1992). More recent estimates assume a population size of 150,000–275,000 (~212,500) individuals, and the International Waterbird Census (IWC) count totals were around 96,000–226,000 individuals between 2011 and 2015 (Wetlands International 2018). Other results based on annual counts indicate that the current number is closer to 150,000 individuals ± 30,000 (Nagy et al. Reference Nagy, Flink and Langendoen2014). In our calculations we used the most optimistic population assessment available – 212,500 individuals. The long-term trend (1988–2012) of this population has been defined as a steep decline. The population dropped sharply between 1993 and 1998, after which it fluctuated significantly between 50,000 and 250,000 from 1998 to 2012 (Nagy et al. Reference Nagy, Flink and Langendoen2014). Currently, there are two independent assessments of the trajectory of the population since 2000: one indicates that it is stable/fluctuating, the other that it is decreasing (Wetlands International, 2019).

Calculation of potential biological removal

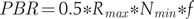

To calculate the value of the potential biological removal (PBR), we used the following formula after Dillingham and Fletcher (Reference Dillingham and Fletcher2008) and Runge et al. (Reference Runge, Sauer, Avery, Blackwell and Koneff2009):

$$ PBR=0.5\ast {R}_{max}\ast {N}_{min}\ast f $$

$$ PBR=0.5\ast {R}_{max}\ast {N}_{min}\ast f $$where Rmax – maximum potential rate of population growth; Nmin – minimum population abundance; f – a coefficient in the range 0.1 – 1 reflecting the status of the population and its priority protection.

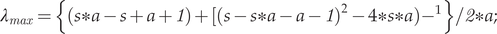

To assess Rmax, we first need to calculate ʎmax using the following formulas (Dillingham and Fletcher, Reference Dillingham and Fletcher2008):

$$ {\lambda}_{max}=\left\{\left(s\ast a-s+a+ 1\right)+[(s-s\ast a-a- 1{)}^2-4\ast s\ast a\operatorname{}),{-}^1\right\}/ 2\ast a; $$

$$ {\lambda}_{max}=\left\{\left(s\ast a-s+a+ 1\right)+[(s-s\ast a-a- 1{)}^2-4\ast s\ast a\operatorname{}),{-}^1\right\}/ 2\ast a; $$ $$ {R}_{\mathit{\max}=}{\lambda}_{max}-1 $$

$$ {R}_{\mathit{\max}=}{\lambda}_{max}-1 $$a – age of first breeding; s – adult survival.Nmin is a conservative estimate of the lower boundary of the population size within a 60% confidence interval if there is one number that specifies the size of the population, or the use of a lower value if there is a range (Dillingham and Fletcher, Reference Dillingham and Fletcher2008). In our case we used the range of population abundance, so we took the lower values of this range. For this species, we used Nmin based on the Wetlands International (2018) database, which is 150,000 individuals.

Age-structured matrix population model

The population viability analysis was based on the stochastic matrix population model (Flint Reference Flint, Savard, Derksen, Esler and Eadie2015). The basic features of this model are as follows: (i) only females defined in the population as 45% of birds were used for calculations in the model (Alexander Reference Alexander1983, Stempniewicz Reference Stempniewicz1994) (ii) population assessments refer to the pre-breeding census conducted during the January count (iii) assuming the age structure in the spring population to consist of two age classes: first-year birds (last year's young birds in the second calendar year of life), two-year-old birds (in the third calendar year of life) and older; (iv) stochastic variability of survival and fecundity parameters.

This model, in the matrix record, took the following form:

$$ \left[\begin{array}{c}N{1}_{T+1}\\ {}N{2}_{T+1}\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\mathrm{F}1& \mathrm{F}2\\ {}\mathrm{s}1& s2\end{array}\right]\ast \left[\begin{array}{c}\begin{array}{c}N{1}_T\\ {}N{2}_T\end{array}\end{array}\right] $$

$$ \left[\begin{array}{c}N{1}_{T+1}\\ {}N{2}_{T+1}\end{array}\right]=\left[\begin{array}{cc}\mathrm{F}1& \mathrm{F}2\\ {}\mathrm{s}1& s2\end{array}\right]\ast \left[\begin{array}{c}\begin{array}{c}N{1}_T\\ {}N{2}_T\end{array}\end{array}\right] $$where: $ N{1}_{T+1} $ – the number of age class 1 (first-year) birds in year T + 1;

$ N{1}_{T+1} $ – the number of age class 1 (first-year) birds in year T + 1;  $ N{2}_{T+1} $ – the number of age class 2 (two-year and older) birds in year T + 1;

$ N{2}_{T+1} $ – the number of age class 2 (two-year and older) birds in year T + 1;  $ N{1}_T $ – the number of age class 1 (first-year) birds in year T;

$ N{1}_T $ – the number of age class 1 (first-year) birds in year T;  $ N{2}_T $ – the number of age class 2 (two-year and older) birds in year T;

$ N{2}_T $ – the number of age class 2 (two-year and older) birds in year T;  $ s1- $survival of birds in the second year of life, hatched in year T, from the moment of performing the pre-breeding census (prior to breeding) in year T + 1 to the beginning of the next breeding season in year T + 2

$ s1- $survival of birds in the second year of life, hatched in year T, from the moment of performing the pre-breeding census (prior to breeding) in year T + 1 to the beginning of the next breeding season in year T + 2 $ ; s2- $survival of birds in the third year of life and subsequent n years of life, hatched in year T, from the moment of performing the pre-breeding census (prior to breeding) in year T + 2 to the beginning of the next breeding season in year T + 3, or in years T + 2 + n to T + 3 + n;

$ ; s2- $survival of birds in the third year of life and subsequent n years of life, hatched in year T, from the moment of performing the pre-breeding census (prior to breeding) in year T + 2 to the beginning of the next breeding season in year T + 3, or in years T + 2 + n to T + 3 + n;  $ F1- $productivity of birds in the first-year of life (in year T + 1, if the year of hatching was year T);

$ F1- $productivity of birds in the first-year of life (in year T + 1, if the year of hatching was year T);  $ F2- $productivity of birds in the second and later years of life (in year T + 2, if the bird was hatched in year T).

$ F2- $productivity of birds in the second and later years of life (in year T + 2, if the bird was hatched in year T).

The productivity of the individual age classes was defined as:

$$ Fn=\left({prop}_n\ast sr\ast {cs}_n\ast {ns}_n\ast chs\ast s0\right)+\left(\left(\ 1\hbox{-} {ns}_n\right)\ast {re}_n\ast {cs}_n\ast {ns}_n\ast chs\ast s0\right) $$

$$ Fn=\left({prop}_n\ast sr\ast {cs}_n\ast {ns}_n\ast chs\ast s0\right)+\left(\left(\ 1\hbox{-} {ns}_n\right)\ast {re}_n\ast {cs}_n\ast {ns}_n\ast chs\ast s0\right) $$where: $ Fn- $age class: F1, F2;

$ Fn- $age class: F1, F2;  $ pro{p}_n- $probability of a female attempting a brood: one-year-old (prop 1), two or more years old (prop 2);

$ pro{p}_n- $probability of a female attempting a brood: one-year-old (prop 1), two or more years old (prop 2);  $ sr- $proportion of females in the brood assumed 0.5 as the model includes only females); csn - clutch size (the number of eggs from which ducklings hatched): mean clutch size for one-year-old females (cs1), mean clutch size for two-year-old or older females (cs2) ;nsn - survival probability of a nest with eggs from the moment when the eggs were laid to when the chicks hatched: one-year-old females (ns1), two-year-old or older females (ns2);

$ sr- $proportion of females in the brood assumed 0.5 as the model includes only females); csn - clutch size (the number of eggs from which ducklings hatched): mean clutch size for one-year-old females (cs1), mean clutch size for two-year-old or older females (cs2) ;nsn - survival probability of a nest with eggs from the moment when the eggs were laid to when the chicks hatched: one-year-old females (ns1), two-year-old or older females (ns2);  $ chs- $probability of a chick surviving from hatching to fledging; s0 - juvenile survival (from fledging to 1st spring); ren - probability of re-nesting (if the first clutch was lost) by one-year-old females re1, or by two-year-old or older females re2.

$ chs- $probability of a chick surviving from hatching to fledging; s0 - juvenile survival (from fledging to 1st spring); ren - probability of re-nesting (if the first clutch was lost) by one-year-old females re1, or by two-year-old or older females re2.

The input variables used for the stochastics trials were assigned different distributions: (i) csn was normally distributed, (ii) propn, sn, nsn, chs were beta distributed and ren , sr were entered as constant values. The  $ {s}_n $ parameters in the simulation with the harvest rate H > 0 was modified

$ {s}_n $ parameters in the simulation with the harvest rate H > 0 was modified  $ s={s}_n\ast \left(1-H\right) $ to model the simultaneous exposition to natural mortality and bycatch (Lebreton Reference Lebreton2005).

$ s={s}_n\ast \left(1-H\right) $ to model the simultaneous exposition to natural mortality and bycatch (Lebreton Reference Lebreton2005).

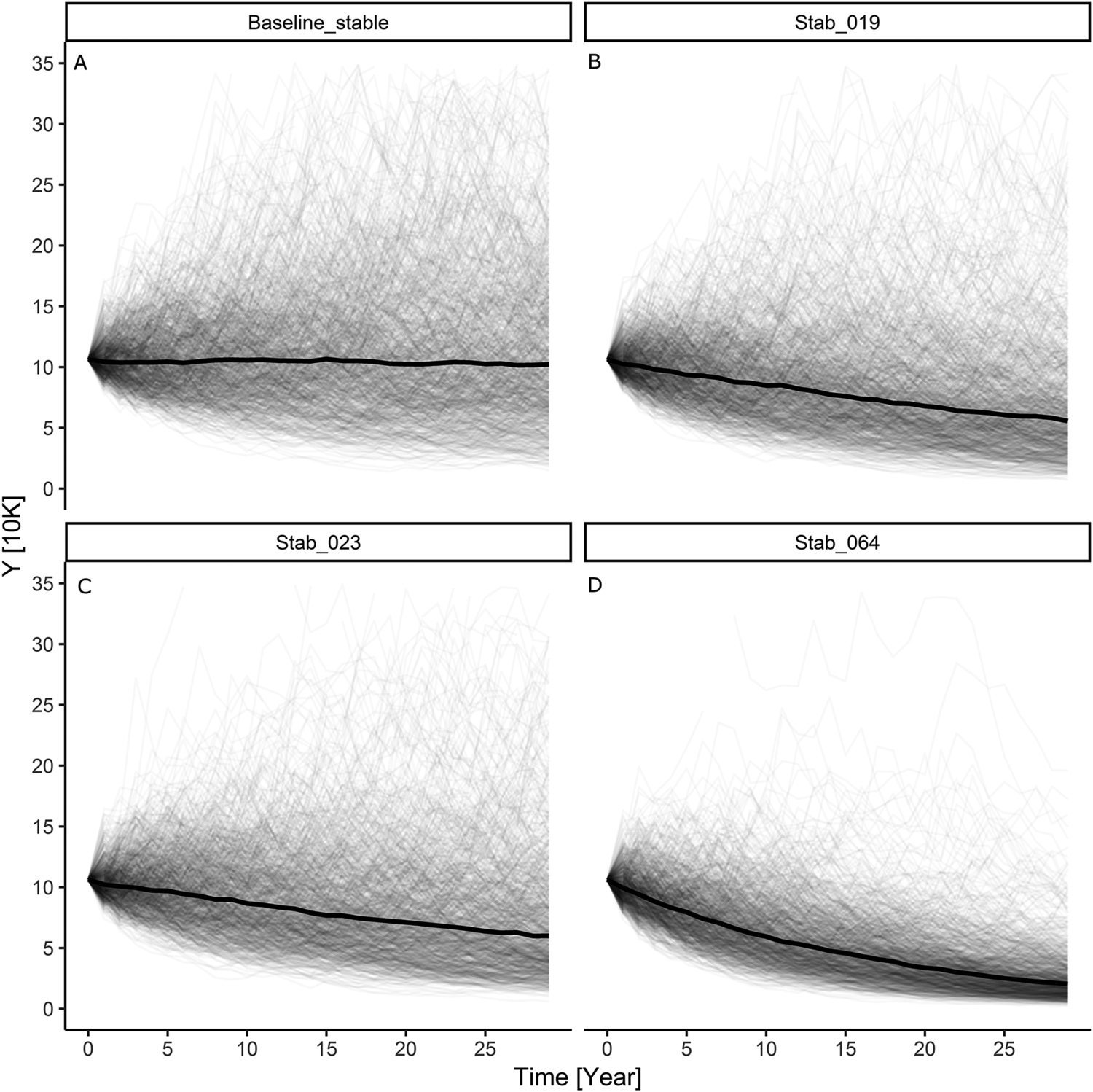

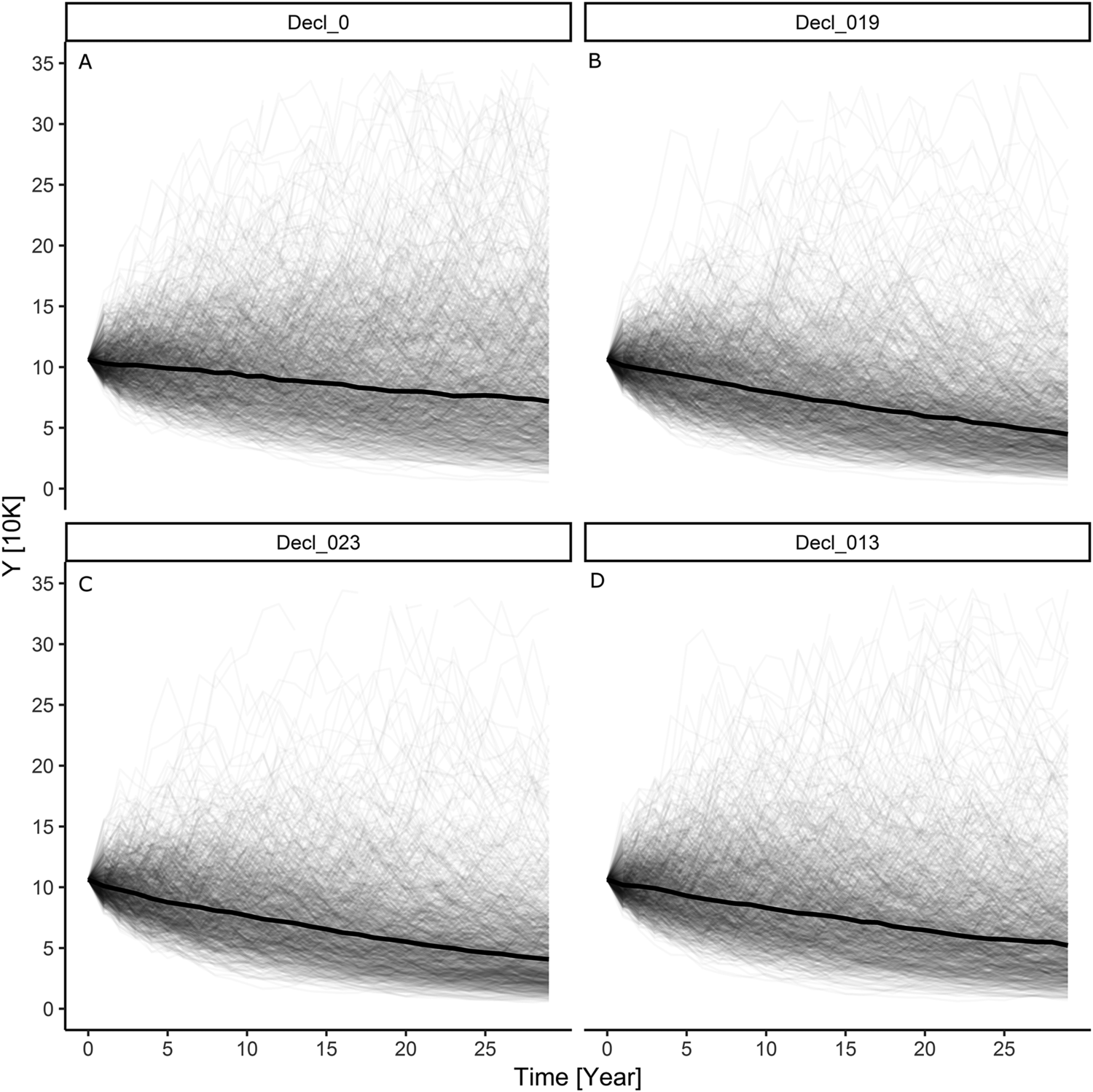

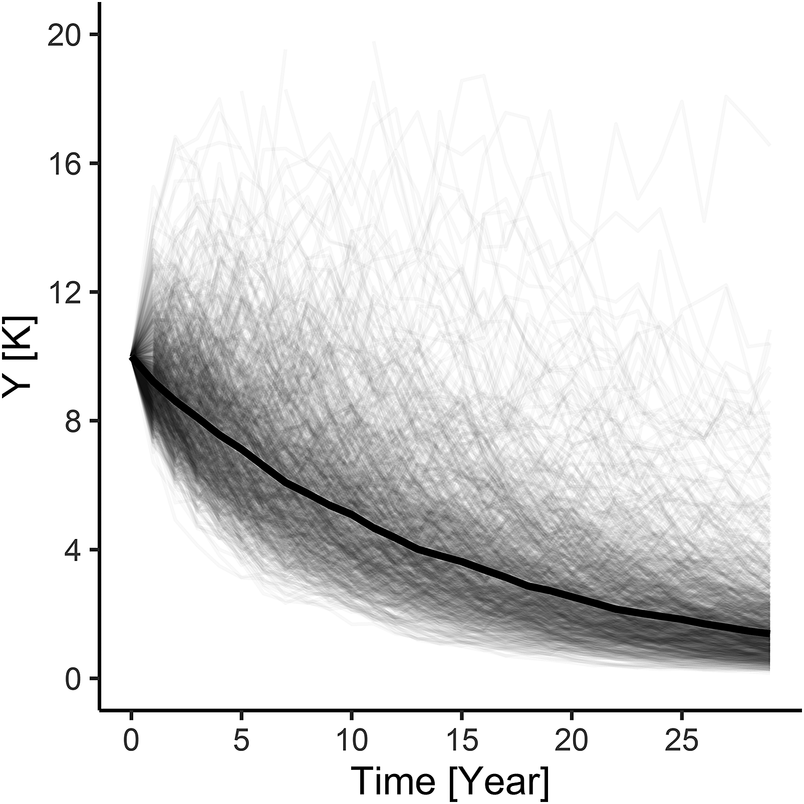

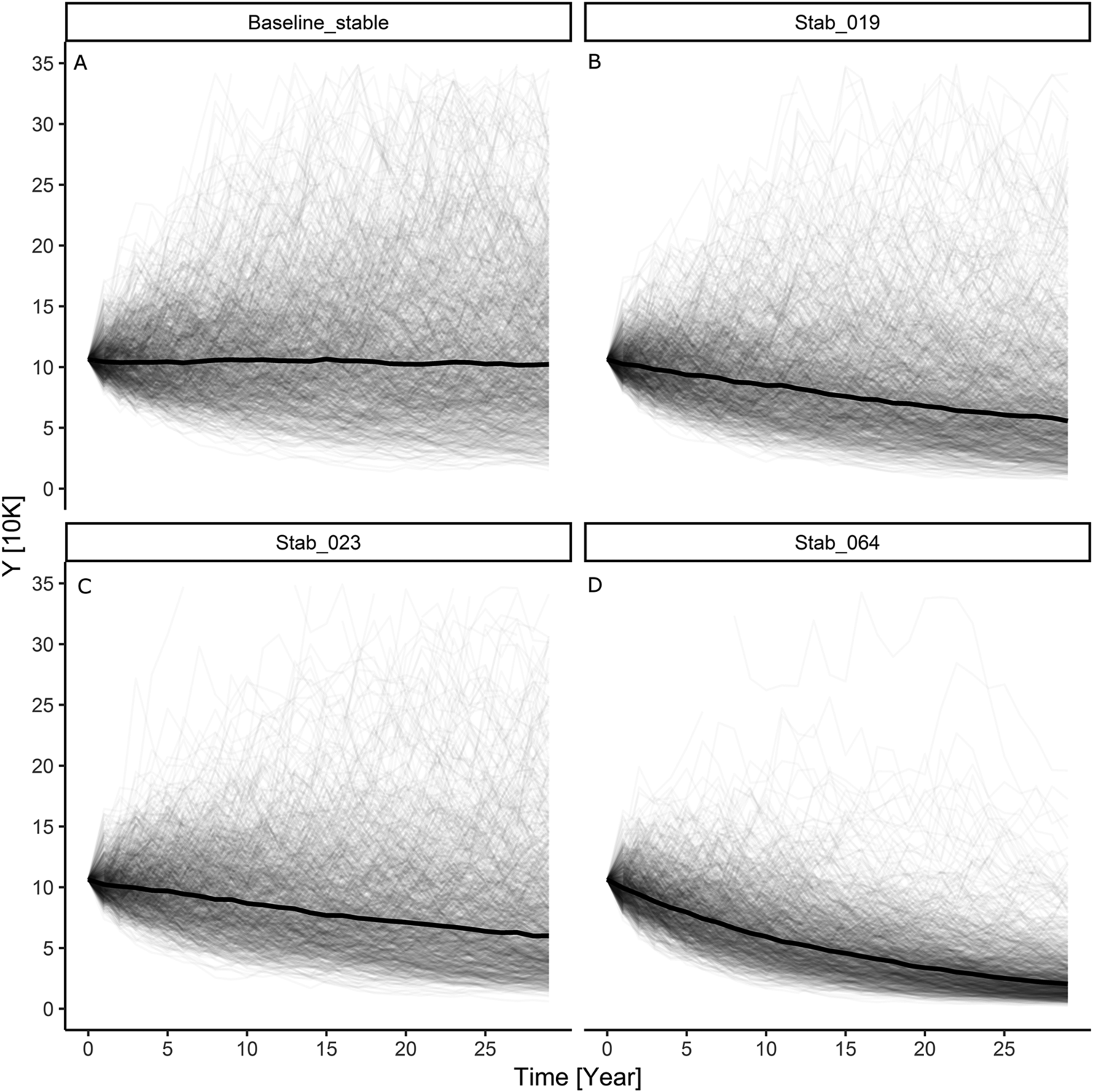

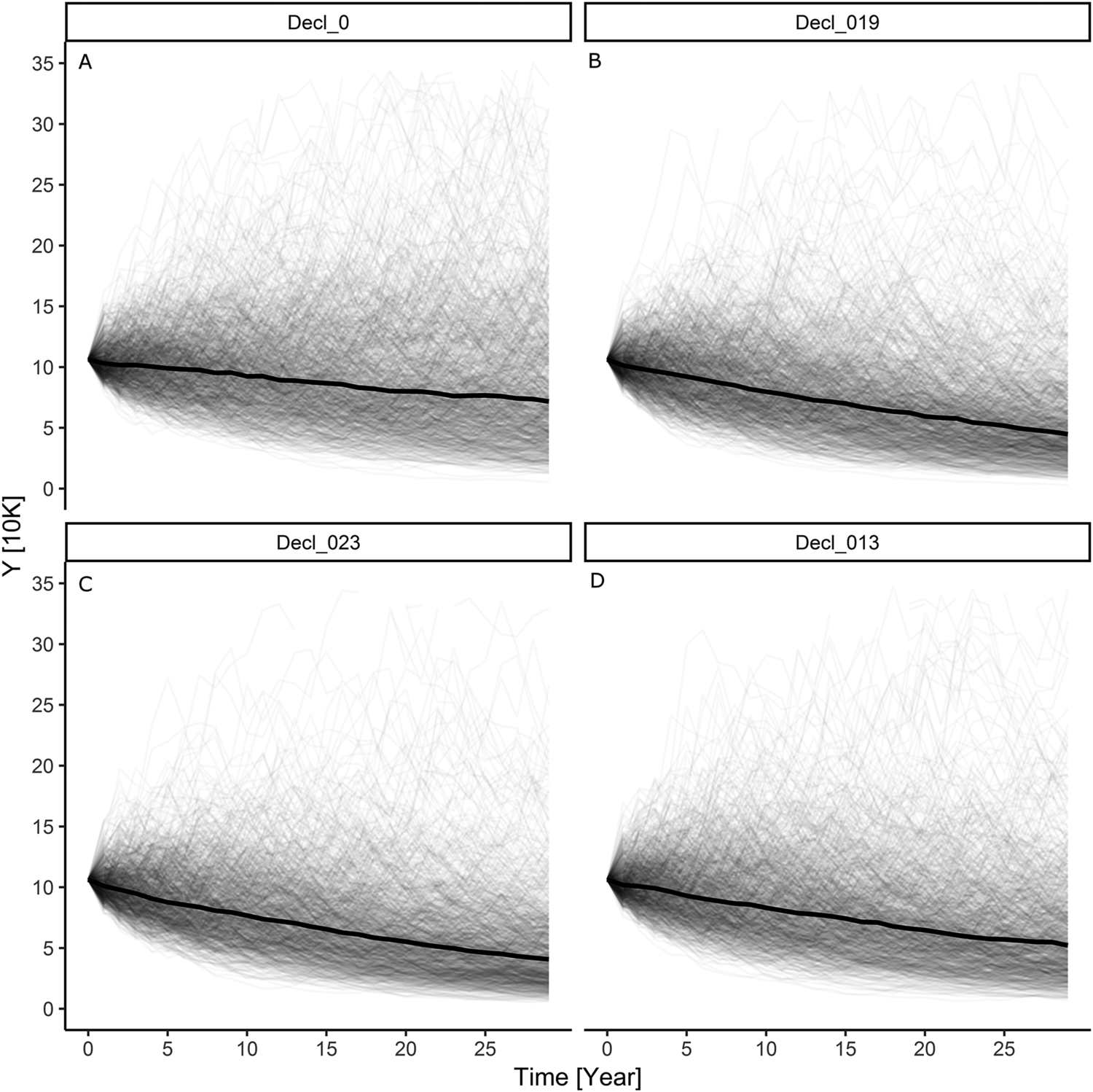

We started population simulations by establishing two hypothetical baseline scenarios, with birds not exposed to additional mortality from bycatch (H = 0). In the first case (Stab_0), the population was effectively stable (median λ on the level of 0.9999; median population after 30 years higher by 11% than initial one). Demographic parameters selected for this stable population were based mainly on Flint et al. (Reference Flint, Grand, Fondell and Morse2006), with slight modifications (see Table S4 in the online Supplementary Material). In the second case (Decl_0), the baseline population was declining at the rate similar to the one actually observed for the population wintering in north-west Europe (λ = 0.9863), based on comparisons of estimates for early 1990. and 2012 (Wetlands International 2019). The decline was simulated by lowering the mean breeding success values for stable population (Stab_0), while keeping survival parameters unchanged.

Against this two baseline scenarios, we simulated the effects of harvest from bycatch, using the harvest rates estimated for the flyway population in this study (min, max) and a harvest rate deemed safe according to the PBR calculations with recovery factor f = 0.5 (stable population) and 0.1 (decreasing population), respectively. This resulted in three scenarios for an initially stable population (Stab_019, Stab_023, Stab_064) and three scenarios for a population declining prior to being exposed to the bycatch (Decl_019, Decl_023, Decl_013).

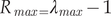

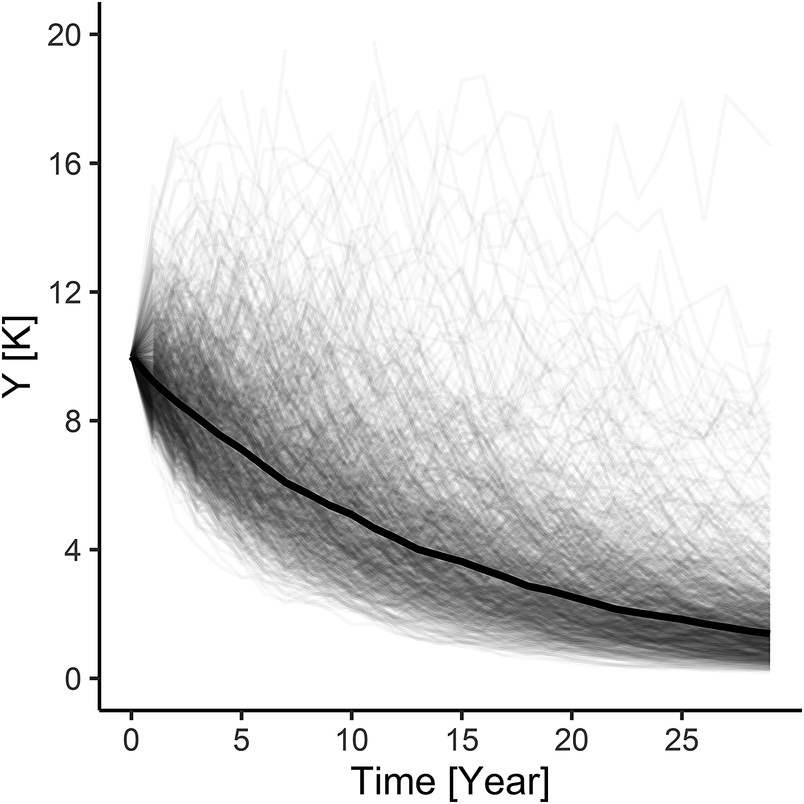

Finally, we simulated changes in a population wintering on the Szczecin Lagoon, Poland, starting from a demographically stable population (λ = 0.9999) that was then exposed to the bycatch intensity actually found in this area during the winter 2013/2014 (Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017). As our population models do not allow for emigration and immigration, by doing so we tried to show the real effects of bycatch to the local population of Szczecin Lagoon, which in natural set-up is likely to be masked by immigration from less harvested populations wintering around (Bicknell et al. Reference Bicknell, Knight, Bilton, Campbell, Reid, Newton and Votier2014).

We took 95,625 to be the population of females (45% of all birds) in all the above scenarios, except for the Szczecin Lagoon where it was set to 9,000 females (Marchowski et al. Reference Marchowski, Ławicki, Kaliciuk, Guentzel and Kajzer2018). Each scenario (baseline and further) was set for a time window of 30 years with 1,000 iterations.

Following Flint et al. (Reference Flint, Grand, Fondell and Morse2006) we did not introduce density-dependence into our Scaup population models, although we are aware of results suggestive of fecundity being density-dependent in this species (Gardarsson and Einarsson Reference Gardarsson and Einarsson2004). Without detailed knowledge of the form of density-dependence, this would result in undue proliferation of possible scenarios. Still, importance of density-dependence for duck population dynamics is debatable (Lawrence et al. Reference Lawrence, Gramacy, Thomas and Buckland2013, Pöysä et al. Reference Pöysä, Rintala, Johnson, Kauppinen, Lammi, Nudds and Väänänen2016).

The results of population viability analyses are given as the following indices: population numbers after 30 years (median); annual rate of population change (stochastic), λ (median); the probability of quasi-extinction defined as 50% of the input population in a time window of 30 years. The latter value loosely relates to the IUCN criterion A2 based on 30% decline threshold: if the population is reduced by 30% over three generations, the species should be considered ‘Vulnerable’ (BirdLife International 2018). With Greater Scaup’s average generation time estimated at 8.2 years (BirdLife International 2018), 30 years is equivalent to 3.7 generations. We took the demographic parameters used in our age-structured model from the following publications: Fournier and Hines Reference Fournier and Hines2001, Flint et al. Reference Flint, Grand, Fondell and Morse2006, Flint Reference Flint, Savard, Derksen, Esler and Eadie2015, Horswill and Robinson Reference Horswill and Robinson2015 (Table S4 and Table S5).

Bycatch estimation method for limited data: Predictable bycatch estimate

Previous studies have shown that the bycatch composition in Lakes IJsselmeer and Markermeer corresponded to the distribution patterns of species like diving ducks, mergansers and grebes (Klinge and Grimm Reference Klinge and Grimm2003). Stempniewicz (Reference Stempniewicz1994) and Degel et al. (2010) showed that the number of drowned birds is positively related to total abundance in the area, so we assumed bycatch to be a good indicator of abundance. Having examined the catches from 70% of fishing boats (n = 230) in the Gulf of Gdańsk, Poland, Stempniewicz (Reference Stempniewicz1994) indicated that birds caught in nets made up 10–20% of the peak numbers recorded in the field. Fishing effort is, in turn, correlated with bycatch size: this statement is based on data from the Szczecin Lagoon, Poland in 2013/2014 (Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017) (Pearson's correlation was 0.917, P = 0.01).

Knowledge of fishing effort (mostly using gillnets) can therefore be a robust estimator of bycatch so long as there is information on the abundance of diving birds. We assumed that fishermen operated in the same way as in the reference period and made no attempts to reduce bycatches. Having reliable information on bycatches from a given reference site to hand (e.g. Stempniewicz Reference Stempniewicz1994), we translated it to the target areas. Regarding these, we knew 1) the number of birds, 2) the number of fishing vessels (assuming the fishing effort per vessel was similar) or fishing effort (then we do not need the assumption about fishing effort per vessel), and 3) the surface area of the water body. The following conditions must also be met: a) areas where fishing nets are set must overlap the area occupied by birds, b) birds in these areas must forage (dive for food). Using this information, we were able to estimate the bycatch size using the following formula:

$$ PBE={B}_r\ast \frac{S_r}{S_t}\ast \frac{N_t{F}_t}{N_r{F}_r} $$

$$ PBE={B}_r\ast \frac{S_r}{S_t}\ast \frac{N_t{F}_t}{N_r{F}_r} $$where PBE – Predictable Bycatch Estimate; Br – number of bycatches in the reference area, St – size of target area; Sr – size of reference area; Nt – number of birds in the target area; Nr – number of birds in the reference area; Ft – number of fishing vessels (or fishing effort) on the target water body; Fr – number of fishing vessels (or fishing effort) on the reference water body.

Results

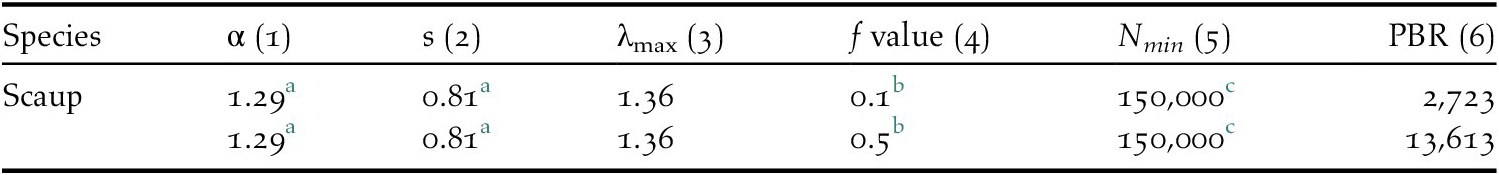

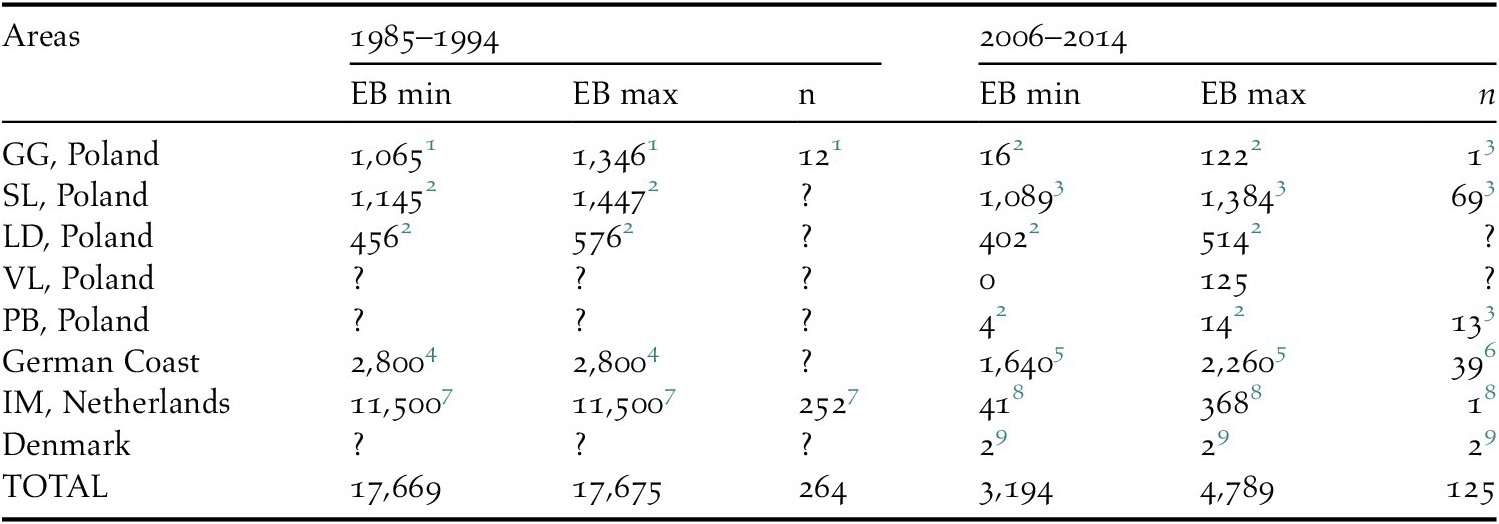

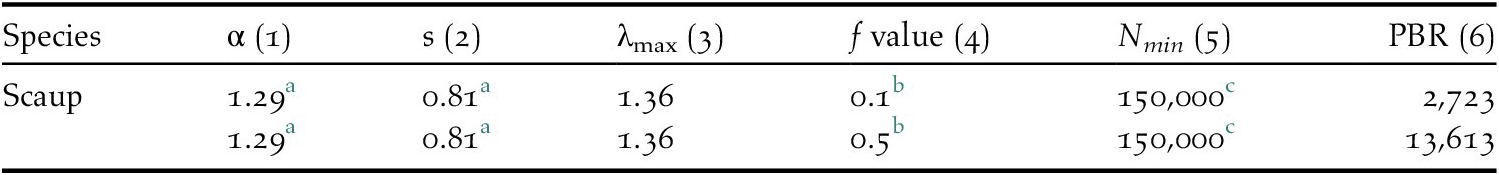

Current estimates of the numbers of bycaught birds yield a result in the range of 3,194–4,789 (mean 3,991) bycaught Greater Scaup per year (Table 1). The highest bycatch was estimated for the German coast and the Odra Estuary in Poland – both were jointly responsible for 86–97% of the total bycatch assessed. The PBR for Greater Scaup for the population wintering in north-west Europe is 2,723 birds using a recovery factor of f = 0.1 for a vulnerable population and 13,613 birds using f = 0.5 for a stable population (Table 2).

Table 1. Estimated bycatch of Greater Scaup Aythya marila for two periods: 1985–1994 and 2006–2014 in the most important sites for populations wintering in north-western Europe.

EB – estimated bycatch, n – number of bycaught birds, GG – Gulf of Gdańsk, SL – Szczecin Lagoon, LD – Lake Dąbie, VL – Vistula Lagoon, PB – Pomeranian Bay, IM – IJsselmeer and Markermeer

1 Stempniewicz, Reference Stempniewicz1994.

2 Estimated by the authors using available data, see Tables S1 and S2 for details.

3 Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017.

4 Grimm, Reference Grimm1985.

5 Calculated by the authors using available figures from Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister and Stipniece2009 and Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012.

6 Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012.

7 van Erden et al. Reference van Erden, Dubbeldam and Muller1999.

8 Van den Boogaard et al. Reference van den Boogaard, Krijgsveld, van Rijn and Boudewijn2013.

9 Petersen and Nielsen, Reference Petersen and Nielsen2015.

Table 2. Demographic parameters used to compute PBR values for Greater Scaup Aythya marila (1) Age of first reproduction, (2) adult survival, (3) maximum annual growth rate, (4) recovery factor, (5) estimate of biogeographical populations wintering in north-western Europe, and (6) Potential Biological Removal values.

a Flint et al. Reference Flint, Grand, Fondell and Morse2006.

b Dillingham and Fletcher Reference Dillingham and Fletcher2008 – f = 0.1 for a vulnerable population, f = 0.5 for a stable population.

c Wetlands International 2017.

Our simulation results indicate that with an initially stable baseline Greater Scaup population, the additional mortality caused by the above bycatch would result in a population decline of 32%–40% (~36%) over a 30-year period and the quasi-extinction probability would be in the range of 42%–50% (Table S3; Figures 1B and 1C). However, for a declining baseline population, the estimated bycatch would result in a decline of 54%–59% (~57%) over a 30-year period and the quasi-extinction probability would be in the 66–71% range (Table S3; Figures 2B and 2C).

The model simulation for an initial Greater Scaup population with an annual growth rate of λ = 0.9863 (a moderate decline) and added harvest rate according to a PBR threshold of f = 0.1 had indicating a population decline of 47% over 30 years and a 58% probability of quasi-extinction (Table S3; Figure 2D). The simulation for an initial population with an annual growth rate of λ = 0.9999 (stable) and added harvest rate according to a PBR threshold of f = 0.5 had indicating a population decline of 78% over 30 years and a 91% probability of quasi-extinction (Table S3; Figure 2D).

Figure 1. The results of modelling individual simulations of the Greater Scaup Aythya marila population overwintering in northern and western Europe in four simulation scenarios: A) stable population currently with no bycatch H = 0: λ = 0.9999; B) stable population with mean bycatch H = 0.019: λ = 0.9836; C) stable population with maximum bycatch H = 0.023: λ = 0.9788; D) stable population with harvest rate computed as bycatch limit of PBR H = 0.064: λ = 0.9462.

Figure 2. The results of modelling individual simulations of the Greater Scaup Aythya marila population overwintering in northern and western Europe in four simulation scenarios: A) declining population with no bycatch H = 0: λ = 0.9863; B) declining population with mean bycatch H = 0.019: λ = 0.9702; C) declining population with maximum bycatch H = 0.023: λ = 0.9664; D) initially declining population with harvest rate computed as bycatch limit of PBR H = 0.013: λ = 0.9751.

Discussion

The annual bycatch value for the north-west European Greater Scaup population is 3,991 (3,194–4,789) individuals exceeding the PBR value for f = 0.1, which is 2,723, while for parameter f = 0.5, the allowable harvest value is 13,613 individuals. Since the latter value is much higher than our estimated bycatch, we conclude that the Greater Scaup's situation is more or less stable. However, our population model results also indicate that additional mortality close to the values calculated using PBR will significantly affect the Greater Scaup population. In particular, the value of PBR with a recovery factor f = 0.5 will lead to 78% decrease in the stable population within 30 years (Table S3), which in practice is tantamount to the extinction of this population in the near future. Thus, in the case of this Greater Scaup population, the use of the recovery factor f = 0.5 (13,613 ind., see also Table 2) is highly inadvisable: a stable population sustaining such a loss will decrease by nearly 80% and would be classified as regionally ‘Endangered’ (EN) and very close to regionally ‘Critically Endangered’ (CR), using IUCN criteria (IUCN Standards and Petitions Subcommittee Reference Subcommittee2014). The fact that numbers are approaching the value calculated with f = 0.1 (2,700 ind.) should already raise legitimate concerns about maintaining the Greater Scaup population in good condition. Our results show that PBR as an indicator of population vitality does not work in the case of the studied Greater Scaup population because the PBR-informed allowable bycatch values have a significantly negative impact on the population (see Figures 1D and 2D), a conclusion similar to that drawn by O'Brien et al. (Reference O’Brien, Cook and Robinson2017). Even with the use of a PBR-calculated value at prudence recovery factor f = 0.1, our ASMM showed that the population will decrease by 47% in 30 years (Figure 2D and Table S3), which qualifies such a population as regionally ‘Vulnerable’ (VU), and very close to regionally ‘Endangered’ (EN) according to IUCN criteria, which is also not an optimistic forecast. PBR probably works best for populations exhibiting a high degree of density-dependence, while dynamics of many waterfowl populations is driven mainly by environmental variation (Pöysä et al. Reference Pöysä, Rintala, Johnson, Kauppinen, Lammi, Nudds and Väänänen2016, see also O’Brien et al. Reference O’Brien, Cook and Robinson2017 for more discussion).

Forecasts for the coming years using bycatch values estimated in this article also do not look too optimistic. Our calculations indicate that in the case of an initially stable population of Greater Scaup, the estimated bycatch will have a significant negative impact on the population over 30 years (~36% decrease, which qualifies for the regional ‘Vulnerable’ category), and with a declining population at recently observed rate, the quasi-extinction threshold (50%) will be exceeded during this period (~57% decrease, which qualifies for the regionally ‘Endangered’ category).

In our models we used optimistic parameter values, mostly based on Flint et al. (Reference Flint, Grand, Fondell and Morse2006). Data from other studies indicate that several demographic parameters may often be lower than those we used. Adult female survival was estimated at 0.67–0.70 (Kessel et al. Reference Kessel, Rocque, Barclay, Poole and Gill2002) or 0.60–0.83 (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Afton, Anderson, Clark, Custer, Lawrence, Pollard and Ringelman2000), rather than 0.81 used in our models. Similarly, the proportion of first year breeders may be lower than 0.75 we used, as 1-year old females constitute only 1% of breeders on Iceland (Bengtson Reference Bengtson1972). Breeding propensity of adult breeders may also be lower than our 0.99, as about 11% of females skip breeding on Iceland (Bengtson Reference Bengtson1972). Re-nesting propensity was 38% on Iceland (Bengtson Reference Bengtson1972), lower than the 51% in Alaska (Flint et al. Reference Flint, Grand, Fondell and Morse2006). Substituting these alternative parameter estimates into our models we would obtain a much more pessimistic picture. On the other hand, introducing some form of negative density-dependence into our models would result in simulated population trajectories leveling-off after some time rather than declining continuously. This may result in slightly less dramatic declines than we obtained. Thus, the exact values of prognosed declines may vary depending on the refinements of demographic models. Yet, we are confident that the general message will hold: current levels of bycatch pose a serious threat to sustainability of Greater Scaup population wintering in north-west Europe. This is clearly shown by the comparison proposed by BirdLife International thresholds of mortality rate from incidental bycatch, which should be no more than 1% of natural annual adult mortality of the species (Birdlife International 2019). This value for the north-west European Greater Scaup population is 403 individuals per year which is 10 times less than our estimated annual bycatch of around 4,000.

The available data (Marchowski et al. Reference Marchowski, Jankowiak, Wysocki, Ławicki and Girjatowicz2017, Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017) indicate that the estimated proportion of bycaught Greater Scaup in the Odra Estuary ranges from 5.5% to 6.9% of the average number of Scaup overwintering in the study area (mean: 6.2%). This is lower than the lower band of values given by other authors, who estimated bycatch mortalities of diving birds in fisheries ranging between 8% and 20% (Kirchhoff Reference Kirchhoff1982, Grimm Reference Grimm1985, Stempniewicz Reference Stempniewicz1994, Žydelis Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister and Stipniece2009). The proportion for Scaup in the Gulf of Gdańsk (Poland) was 10.6%–13.6% (Stempniewicz Reference Stempniewicz1994).

The above considerations clearly indicate that Greater Scaup bycatch in the north-west Europe flyway population is relatively high, contributing significantly to the overall decline of the population. Although there are many gaps in bycatch data relating to Greater Scaup in Europe owing to the incomplete coverage of the study area, we have gathered all the currently available information. We are also aware that estimating bycatch in the manner presented here is encumbered with a certain degree of error. At the moment, however, there are no better data available, and our results show that the problem is important and worth addressing. Bearing in mind that the wintering and stopover sites of the non-breeding Greater Scaup population of north-west Europe have not been exhaustively studied, the bycatch numbers given here should be treated as a minimum estimate. The amount of available data analysed, however, reflects quite well the scale of the bycatch threat to Greater Scaup because we have used information from most places where significant concentrations of the species coincide with fishing activity.

Our study shows that only one human-caused threat - bycatch in fishing nets - can negatively affect the population of the species to a considerable extent. Bycatch may therefore be the most important danger to the Greater Scaup population in Europe. So far, there is little evidence that bycatch has been associated with the decline in the Greater Scaup population (Afton and Anderson Reference Afton and Anderson2001). Hunting of Greater Scaup is prohibited in most European countries, although Mooij (Reference Mooij2005) estimated that 2,010 individuals are shot in the EU each year. New data indicate that hunting of Greater Scaup is becoming less and less popular: an estimated 659 Greater Scaup have been shot in recent years in Europe (Hirschfeld et al. Reference Hirschfeld, Attard and Scott2019), so this threat is decreasing although it is still the second most important identified anthropogenic factor negatively affecting this Greater Scaup population. Other threats include oil pollution, disturbance from shipping, reductions in food supplies, obstacles in the form of technical structures, disturbance at roosting and foraging sites as a result of tourism and habitat loss (Mendel et al. Reference Mendel, Sonntag, Wahl, Schwemmer, Dries, Guse, Müller and Garthe2008, de Vink et al. Reference De Vink, Clark, Slattery and Wayland2008, Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Perennou and Lutz2009). Fishery bycatch has already been mentioned as posing a danger to Greater Scaup in Europe (Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister and Stipniece2009). In view of the northward and eastward shift of its wintering grounds, one should expect the bycatch problem to increase in regions such as the eastern German Baltic coast and the western Polish coast. This is reflected in the number of bycaught birds in these regions (Table 1). Because of climate warming, the problem can be anticipated to spread further eastwards and northwards, to areas such as the Courland Lagoon and the Gulf of Riga.

Large concentrations of diving birds and the intensive use of water bodies by the fishing industry turn lagoons into sites of potentially large bycatch (Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012). Further increases in the number of Greater Scaup in the Odra Estuary may lead to its increasing mortality; this will need to be taken into consideration when planning conservation measures for this species. In the European Red List of Birds, Greater Scaup is classified as ‘Vulnerable’ (BirdLife International 2015), so planning the human use of an area must take into account the broader aspect of the subject. Looking at the problem of bycatch from a local or even regional (south-western Baltic) perspective, one may get the impression that the situation of a given species is good. There are increasing numbers of Greater Scaup in the Odra Estuary, possibly reaching 100,000 individuals in some years (Marchowski and Leitner Reference Marchowski and Leitner2019), so bycatch of 1,200 individuals per year (Table 1) may seem small. But the increasing numbers of Greater Scaup in this region are related to climate warming and the shift in its wintering range farther to the north and east (Marchowski et al. Reference Marchowski, Jankowiak, Wysocki, Ławicki and Girjatowicz2017). Local effects of increased mortality are quickly compensated by the recruitment of new individuals, so the decrease in numbers caused by the local threat is masked. If, hypothetically, we were to isolate the local Odra Estuary population from outside immigration, at this bycatch level, it would shrink by 99% within 30 years (Figure 3; Table S3), which would involve classifying such a population as regionally ‘Critically Endangered’ according to IUCN criteria (IUCN Standards and Petitions Subcommittee Reference Subcommittee2014). That is why it is important to examine the problem from a more global perspective, at the flyway population level.

Figure 3. Local population of the Greater Scaup Aythya marila from Szczecin Lagoon initially stable with bycatch H = 0.062: λ = 0.9340. Hypothetical situation, with no recruitment from outside.

In 2009, the European Commission issued a technical document – the management plan for Greater Scaup 2009–2011 (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Perennou and Lutz2009). It stated that fishery bycatch was one of the possible reasons for the species’ decline and expressed the need to restrict fishing activities to reduce bycatch in areas of its regular occurrence. In 2011–2012, work on the management plan for the Szczecin Lagoon (Special Protected Area Natura 2000) in Poland – one of the most important areas for wintering Greater Scaup in Europe (Skov et al. Reference Skov, Heinänen, Žydelis, Bellebaum, Bzoma, Dagys, Durinck, Garthe, Grishanov, Hario, Kieckbusch, Kube, Kuresoo, Lasson, Luigujoe, Meissner, Nehls, Nilsson, Petersen, Roos, Pihl, Sonntag, Stock, Stipniece and Wahl2011) – was undertaken. The plan contains specific restrictions for fisheries designed to protect Greater Scaup, including the temporary prohibition of the use of gillnets in the areas most frequently used by Greater Scaup (about 15% of the total Natura 2000 area) during the period when the largest flocks of Greater Scaup occur, i.e. between 15 October and 15 April (Ławicki et al. Reference Ławicki, Guentzel and Wysocki2012). But protests from fishermen and the communities associated with them meant that the government did not implement the proposed recommendations and approval of the plan is still pending.

Some hope is offered by recent short-term trends: for the period 2000–2012, Wetlands International (2018) states the trend of the Greater Scaup population as fluctuating-stable, while Nagy et al. (Reference Nagy, Flink and Langendoen2014) report even a short-term steeply increasing trend in the period 2003–2012. This may be related to the reduction of fishing effort in the south-western Baltic Sea (Bellebaum et al. Reference Bellebaum, Schirmeister, Sonntag and Garthe2012), and the reduction in bycatch in Lakes IJsselmeer and Markermeer in the Netherlands (Klinge and Grimm Reference Klinge and Grimm2003). However, this short-term change should be treated with caution, as it may well represent a swing typical of fluctuating populations, especially since the latest trend assessment indicates a decline in numbers (Wetlands International 2019). An additional element is climate driven distribution changes, which can complicate the trend analyses (Fox et al. Reference Fox, Nielsen and Petersen I2018).

We are certain that bycatch of birds in fishing nets is a big problem and solving it is a great challenge. An important weakness is the lack of data on the size of this phenomenon and estimating the extent of bycatch provides a partial solution. As we mentioned in the introduction, methods for estimating bycatch based on incomplete data have not been introduced so far. However, assessments of the potential risk of bycatch have been developed (Sonntag et al. Reference Sonntag, Schwemmer, Fock, Bellebaum and Garthe2012, Bradbury et al. Reference Bradbury, Shackshaft, Scott-Hayward, Rextad, Miller and Edwards2017). In our work, we show a possible next step: after determining the areas of potential risk, it is also possible to estimate the extent of bycatch of individual species at specific sites. We did this in small, well-known areas, about which we knew that bycatch studies had taken place before (Stempniewicz Reference Stempniewicz1994, Psuty et al. Reference Psuty, Szymanek, Całkiewicz, Dziemian, Ameryk, Ramutkowski, Spich, Wodzinowski, Woźniczka and Zaporowski2017), so we were able to test the results of our model with real bycatch. It can therefore be concluded that the use of our equation is very site-specific. It should be tested on larger areas and in different conditions. In order to obtain reliable estimates, it is very important to calibrate the model, which must be based on real values from bycatch studies.

Conclusion

This work has demonstrated the great significance of Greater Scaup bycatch in fishing nets, so this threat should be regarded as one of the most important reasons for the decline in the north-west European population of this species in the last three decades. The current bycatch value is 10 times higher than the threshold of mortality rate from incidental bycatch recommended by BirdLife International (BirdLife International 2019) indicating non-sustainable mortality for the population. Thus, we can conclude that the population fails to ensure long-term viability. Action to protect Greater Scaup is therefore urgently required. First of all, a bird bycatch monitoring program would be highly desirable in order to address the current high level of bird mortality in fishing nets, and thereafter to define the necessity and detail explicit rules for introducing restrictions on fisheries. The solution should be sought in the periodic exclusion of gillnet fishing from areas defined as most commonly used by birds. These areas do not have to be large, but they should be precisely delimited on the basis of available research, e.g. in the Odra Estuary (see the maps of Greater Scaup distribution in Marchowski et al. Reference Marchowski, Neubauer, Ławicki, Woźniczka, Wysocki, Guentzel and Jarzemski2015 or Marchowski and Leitner Reference Marchowski and Leitner2019). In other, less frequently used areas within the wintering range, effective mitigation techniques such as those presented by Wiedenfeld et al. (Reference Wiedenfeld, Crawford and Pott2015) should be used, e.g. alternative fishing gear designed to reduce the mortality of birds through increased visibility of nets by diving birds, and replacing stand nets with bird-safe fishing gear (i.e. cages, UV illuminated nets, specially marked nets; EU action plan (COM 2012) provides more details, but see Field et al. Reference Field, Crawford, Enever, Linkowski, Martin, Morkūnas, Morkūnė, Rouxel and and Oppel2019.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0959270919000492.

Acknowledgements

A hearty “Thank you” to all those who responded to our request for information about the Greater Scaup bycatch in their countries: Jochen Bellebaum, Simon Cohen, Bernard Deceuninck, Richard Hearn, Menno Hornman, Leho Luigujoe, Rasmus Due Nielsen, Leif Nilsson, Ib Krag Petersen and David Stroud. Peter Senn kindly improved our English. We also thank Ib Krag Petersen, reviewers and editors for valuable comments and suggestions.