Introduction

Commercial fisheries pose several impacts on marine ecosystems, contributing to fish stock depletion and mortality of non-target species (Pauly et al. Reference Pauly, Watson and Alder2005). Fisheries have direct and indirect impacts on marine wildlife. The latter include alterations to several levels of the food web, through overfishing and/or enhanced food availability due to fishery discards (Pauly et al. Reference Pauly, Watson and Alder2005). Direct impacts include injuries or mortality caused by interactions with fishing gear or boats (Williams et al. Reference Williams, Pople, Showler, Dicks, Child, Ermgassen and Sutherland2012) and seabirds are one of the most affected groups (Lewison et al. Reference Lewison, Crowder, Read and Freeman2004). Broadly, seabirds and fisheries utilise the same productive areas, resulting in high levels of trophic and spatial overlap which ultimately may lead to negative interactions. Seabird bycatch has been largely studied over recent decades, becoming an important issue for fisheries management (Pott and Wiedenfeld Reference Pott and Wiedenfeld2017). All those impacts can unbalance top predators’ demographic parameters.

Bycatch is one of the top three threats to seabirds in terms of number of species affected and average impact (Dias et al. Reference Dias, Martin, Pearmain, Bur, Small, Phillips, Yates, Lascelles, Garcia and Croxall2019), with 200,000 birds bycaught per year in European waters alone (ICES 2009). Seabird bycatch occurs with a range of fishing gear, but is higher with longlines, gillnets and trawlers (Lewison et al. Reference Lewison, Crowder, Read and Freeman2004). However, significant gaps still exist in knowledge of seabird bycatch patterns, namely in the artisanal fisheries sector. Despite large-scale fisheries being believed to affect a greater number of seabird species than small-scale fisheries, both sectors seem to have similar impacts on seabirds in terms of severity and scope (Dias et al. Reference Dias, Martin, Pearmain, Bur, Small, Phillips, Yates, Lascelles, Garcia and Croxall2019), although the impacts from small-scale fisheries are generally less well-known (Pott and Wiedenfeld Reference Pott and Wiedenfeld2017). In fact, at a global level, gaps in knowledge of seabird bycatch are more noted in areas where small-scale fisheries are more prevalent. Nevertheless, seabird bycatch has already been reported for some regions, namely the Pacific (Melly et al. Reference Melly, Shigueto, Mangel, Pajuelo, Cáceres, Corrales, Iturrizaga and Baella2006, Moreno et al. Reference Moreno, Arata, Rubilar, Hucke-Geete and Robertson2006), Atlantic (Bugoni et al. Reference Bugoni, Neves, Leite, Carvalho, Sales, Furness, Stein, Peppes, Giffoni and Monteiro2008, Shester and Micheli Reference Shester and Micheli2011) and Mediterranean (Cooper et al. Reference Cooper, Baccetti, Belda, Borg, Oro, Papaconstantinou and Sánchez2003, Cortés et al. Reference Cortés, Arcos and González-Solís2017, Cortés and González-Solís Reference Cortés and González-Solís2018). The main constraints on collecting bycatch data from artisanal fisheries are related to the limitations on accommodating observers on such small-sized vessels.

Despite the little information available on seabird bycatch for several fishing fleets, mortality driven by fishing activity has been considered a main cause of the decline of several seabird populations (Croxall et al. Reference Croxall, Butchart, Lascelles, Stattersfield, Sullivan, Symes and Taylor2012). Seabirds are long-lived, with long generation times, delayed maturity, and low reproductive rates and are particularly sensitive to an increase in adult mortality. Many species rely on relatively limited breeding ranges, yet travel widely outside the breeding season. Such characteristics make this group vulnerable to threats on their breeding grounds, as well as many threats in their non-breeding ranges. Subsequently, understanding and reducing the negative impact of fisheries is a high priority for conservation of marine ecosystems (Weimerskirch et al. Reference Weimerskirch, Brothers and Jouventin1997, Tuck et al. Reference Tuck, Phillips, Small, Thomson, Klaer, Taylor, Wanless and Arrizabalaga2011, Lewison Reference Lewison2013).

Bycatch is known to affect several seabird populations in the North-east Atlantic. However, data are sparse in the Iberian Atlantic and Bay of Biscay (Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Small, Croxall, Dunn, Sullivan, Yates and Black2011, Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Small and French2013, ICES 2017, Pott and Wiedenfeld Reference Pott and Wiedenfeld2017). Occasional bycatch incidents have been reported and some populations have long suffered severe impacts from fishing activity ( Velando and Freire Reference Velando and Freire2002, Munilla et al. Reference Munilla, Díez and Velando2007, Costa et al. Reference Costa, Pereira, Henriques, Miodonski, Vingada and Eira2019). In Portuguese mainland coastal fisheries, bycatch was recently recorded in set nets (including gillnets and trammel nets), demersal longlines, and purse seines (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Henriques, Miodonski, Pereira, Marujo, Almeida, Barros, Andrade, Araújo, Monteiro, Vingada and Ramírez2015). As in other regions, the fisheries sector in Portugal is composed of an artisanal fleet, including a great number of small vessels (Gaspar et al. Reference Gaspar, Pereira, Martins, Carneiro, Pereira, Moreno, Constantino, Felício, Gonçalves, Viegas, Resende, Pereira, Siborro, Cerqueira, Gaspar and Pereira2014). This means that even small average bycatch rates may result in a great number of birds caught every year, causing severe impacts on seabird populations. The effect can be further magnified when these fisheries overlap spatially with areas of endemism and/or low populations (Jaramillo-Legorreta et al. Reference Jaramillo-Legorreta, Rojas-Bracho, Brownell, Read, Reeves, Ralls and Taylor2007). However, bycatch is very hard to study in such small-sized artisanal fisheries and accurate extrapolation for the entire fleet is challenging (Pott and Wiedenfeld Reference Pott and Wiedenfeld2017). Thus, studies to fully understand the bycatch impact by this type of fleet need to focus on smaller areas, include higher observation effort, and be followed by trials on mitigation techniques adapted to the local situation.

The present study aimed to accurately quantify seabird bycatch in Ilhas Berlengas Special Protection Area (SPA) and surrounding waters (hereafter referred as Ilhas Berlengas SPA) and test potential mitigation measures. Considering the impact of longliners and set nets along the Portuguese coast (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Henriques, Miodonski, Pereira, Marujo, Almeida, Barros, Andrade, Araújo, Monteiro, Vingada and Ramírez2015), and the abundance of seabirds in the region (Meirinho et al. Reference Meirinho, Barros, Oliveira, Catry, Lecoq, Paiva, Geraldes, Granadeiro, Ramírez and Andrade2014), we predicted that gannets and shearwaters are likely to be affected by those gears, while purse seines were more likely to affect gulls and small shearwaters (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Henriques, Miodonski, Pereira, Marujo, Almeida, Barros, Andrade, Araújo, Monteiro, Vingada and Ramírez2015). Recently, Martin and Crawford (Reference Martin and Crawford2015) proposed the use of high contrast panels in nets to reduce bycatch, based on the sensory capacities of seabirds, as most species would be able to detect them underwater, even in different light conditions. Considering that longline bycatch occurs while the gear is set (not during hauling/setting), a mitigation measure was proposed by fishermen: darkening the hook to reduce its visibility to small fish. The use of raptor-like scaring devices has had partial success in terrestrial environments, particularly in short-term deployments (Conover Reference Conover1979), but has never been tested at sea. Therefore, in this study, three different mitigation measures were tested: high contrast panels in gillnets, black hooks in longlines and a bird scaring device in purse seines. We predicted a reduction in relation to the number of birds captured in longlines and nets where mitigation was implemented. The efficacy, practical applicability, and economic viability were tested for each measure. The effect on seabird interactions with fishing boats was assessed by comparing paired fishing events with and without implementation of the mitigation measure.

Methods

Study site

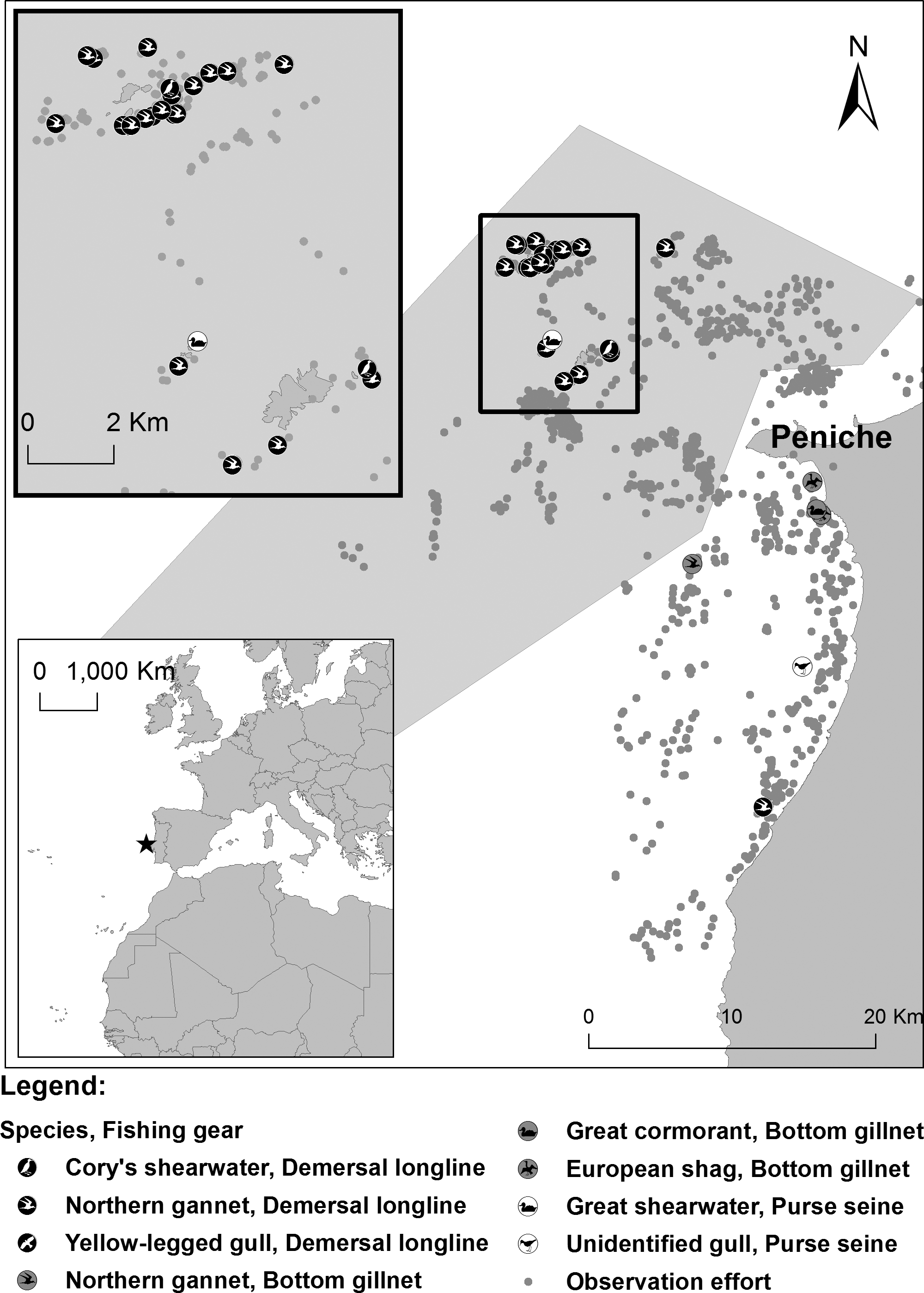

Ilhas Berlengas SPA is located off the mainland of Portugal and includes the Berlengas archipelago and a large marine area of 102,668 ha (Figure 1). The outer boundary is located 43 km from Peniche, and the inner one at 7.5 km. Climatically, the area is where Atlantic and Mediterranean climates converge. Its intense seasonal coastal upwelling supports high biological productivity. The islands are important seabird breeding grounds (Cory´s Shearwater Calonectris borealis, European Shag Gulosus aristotelis, Yellow-legged Gull Larus michahellis and Band-rumped Storm-petrel Hydrobates castro), and host numerous migratory and/or wintering populations of other seabird species including the Northern Gannet Morus bassanus, Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus, Lesser Black-backed Gull Larus fuscus and Razorbill Alca torda (Meirinho et al. Reference Meirinho, Barros, Oliveira, Catry, Lecoq, Paiva, Geraldes, Granadeiro, Ramírez and Andrade2014). Historically, the island hosted a breeding population of Common Murre Uria aalge, and gillnets have been suggested as one of the drivers for the local extinction of this species (Munilla et al. Reference Munilla, Díez and Velando2007). Fisheries are one of the main economic activities within the SPA and Peniche, the nearest fishing port, is one of the Portuguese ports with higher fish landings per year and with a diverse fishing fleet. It is estimated that small scale fisheries represent between 20% and 40% of total landings and gillnets are one of the most commonly used fishing gears (Abreu et al. Reference Abreu, Leotte and Arthur2010).

Figure 1. Geographic location of Ilhas Berlengas Special Protection Area (light grey area) and Berlengas archipelago. Grey dots show the spatial distribution of observation effort aboard fishing vessels (location points of the vessel every 15 minutes). The geographical location of seabird bycatch events is also shown.

Data collection aboard fishing boats

Data on characterization of fishing operations and seabird bycatch were recorded from June 2015 to June 2018. Trained observers followed the entire fishing trip in 17 different boats departing from Peniche fishing harbour. The fishing gear sampled included demersal longline (85 trips), bottom gillnets (107 trips) and purse seines (103 trips; see Table 1 for gear details). For the latter, a fishing event was defined as from the moment the net was set in the water until the last fish was taken aboard.

Table 1. Details on the fishing gears targeted by this study, developed in Ilhas Berlengas SPA from June 2015 to June 2018.

In the cases of demersal longlines and bottom gillnets, a fishing event was defined as the setting or the hauling periods separately. Length of boats operating demersal longlines and bottom gillnets was on average 9.03 ± 1.86 m (mean ± SD; n = 6) and 10.66 ± 3.47 m (n = 7), respectively, including the small-scale (<12 m) and medium-scale fishing fleet (≥12 m). Demersal longlines are composed of a series of small floats to keep hooks at a medium position in the water column and fixed to the seabed by one weight at each end of the longline. Bottom gillnets include single, double, and triple netting. Purse seiners included boats longer than 12 m (20.69 ± 4.13 m; n = 5). Observers recorded spatial data during the entire fishing operation as well as the amount of target species captured (in terms of quantity, species, and economic income).

Data on fishing effort

Acknowledging that our observation effort covered less than 1% of the annual fishing effort for the entire fleet, and considering the lack of accurate data obtained when using automatic devices, fishing boat captains were interviewed to improve data for the fleet operating demersal longlines, bottom gillnets and purse seines in the study area. Such an approach allowed us to reach 89% of the fishing fleet operating from Peniche fishing harbour, covering 19–28% of the fleet’s fishing effort. All interviews were carried out in person, by a trained interviewer with extensive knowledge of the fishing sector, and following a standardised, semi-structured questionnaire. The captain of each vessel was interviewed and asked to give information regarding the fishery operations taken during the previous three months, based on what they could remember. This time window was set according to experience from previous projects, which found it was adequate to collect reliable information. Basic information was collected, such as the name and registration number of the vessel, length of boat, the type of fishing gear, list of target and bycatch species. Information regarding fishing effort was also collected, including the number of trips and number of days at sea over the three-month period, the average number of sets and hooks used per fishing trip. Data on spatial distribution of fishing effort was also collected using a 10*10km grid of the study area, where fishermen were asked to mark their main fishing sites used during the same period.

Tests on mitigation measures

Three mitigation measures were tested to reduce seabird bycatch, namely high contrast panels in gillnets, black hooks in longlines and a bird scaring device in purse seines (Figure 2). Paired surveys always included test gear followed by a control gear (with no mitigation), both under the same conditions. This approach was used to reduce bias from other independent variables such as sea conditions, setting depth, season, seabird abundance, distance to land or soaking time. Both test and control were similar in terms of the technical details of the gear, number of hooks, hook size (only for demersal longlines), mesh size and colour (bottom gillnets and purse seines) and length of gear. Moreover, the tested gear was similar to that commonly used by the fishermen involved in this study. Fishermen were given financial compensation to participate in these trials. Monitoring protocols were similar to those used to assess seabird bycatch (as stated before) and followed by the same trained observers.

Figure 2. Mitigation measures tested to reduce seabird bycatch in Ilhas Berlengas SPA. Handmade 0.6 x 0.6 m high contrast panels were fixed to gillnets (A). Black hooks were tested against the most widely used grey hooks (B). A scary-bird device with a harrier shape (SCARYBIRD) was fixed in the top of a purse seiner, using a 6 m long pole and a 1.5 m craft line (C).

Handmade 0.6 x 0.6 m high contrast panels were fixed to gillnets. A panel consisted of five 0.6 x 0.06 m black stripes interspersed with five white stripes, both made of nylon. Panels were attached to the gillnet centre height using nylon fishing line fixed to eyelets placed at each panel corner and spaced every 6 m. Gillnet length (500–1,000 m) and soaking time (6–8 hours) were different among boats but always similar between test and control gear. High contrast panel trials included 29 paired-fishing events aboard three different boats (all <10 m in length) from November 2016 to May 2018, during autumn and winter seasons.

Black hooks were tested against the most widely used grey shine hooks. Hook size and shape were similar. Hooks were spaced ~5 m from each other in a 250–1,000 m demersal longline, resulting in 50 to 200 hooks longline-1. Black hook tests included 12 paired-fishing events aboard three different boats (all <12 m in length) from July 2017 to August 2018, during autumn and winter seasons.

A bird scaring device with a harrier shape (SCARYBIRD) was fixed to the top of a purse seiner, using a 6 m long pole and a 1.5 m craft line. The bird scarer soared in winds above 2 km h-1. Bird scaring tests included 20 paired-fishing events aboard a 17 m boat from April to October 2018. Data on the interaction of seabirds with the fishing operation were also collected for this mitigation measure. All birds observed in the vicinity of the vessel were identified and counted. Counts were taken at 15-minute intervals following a snapshot protocol (Camphuysen and Garthe Reference Camphuysen and Garthe2004) and covering the entire fishing event. Each bird was assigned to a distance band (<100 m; 100–300 m; >300 m) and a behaviour code: directional flight (direct flight with no direct interaction or stop over the fishing area), searching flight (surrounding and/or searching over the fishing area) or diving in the fishing area.

Economic and acceptance data collection

Economic data were collected for the fishing trips performed during the three mitigation measure tests. The costs were calculated for the acquisition of material and attachment of the devices. Costs related to the fishing operation (fuel and crew costs) and the income of landings were obtained for each fishing event. Caught target (commercial prey) species were identified, counted, and weighed. By the end of each survey, a semi-structured interview was performed with the vessel captain. The interview included questions on the ease of using each mitigation measure and its impact on seabird bycatch and catch of target species.

Data analysis

Bycatch and fishing effort data were first divided into strata by gear type, length of boat (<12 m and ≥12 m), seabird species and season. Seasons were split into winter (December to February), spring (March to May), summer (June to August) and autumn (September to November). Bycatch rate was estimated as number of captured birds by the number of observed fishing trips (birds trip-1) and by the number of observed fishing events (birds event-1). For demersal longlines the number of birds per 1,000 hooks (birds*10-3 hooks) was also calculated. No bycatch was observed during setting or hauling of demersal longlines or bottom gillnets, which means that birds were entangled during the time the gear was passively fishing, so only those fishing events where hauling was observed were considered to estimate bycatch rates. Then, length of soaking time was also considered in our estimates of bycatch rates, using the number of captured birds per 1,000 hours (birds*10-3hours) and per 1,000 hooks per 1,000 hours (birds*10-6 hooks*hours). The effects of several variables on bycatch were then evaluated. Since our dataset included a large number of zeros (fishing events or trips with no bycatch), we took a two-step approach. First, we evaluated the effect of fishing gear on bycaught species, distance to land, soaking time, bottom depth, setting depth, season and wind speed (according to the Beaufort scale) on bycatch rate (birds trip-1) using contingency tables and chi-square tests. Due to the low number of birds recorded in bottom gillnets and purse seines, both gears were excluded from the analysis. Only events with observed bycatch were filtered to analyse the effect of continuous variables (distance to land, soaking time, bottom depth, setting depth, wind speed, number of hooks and length of longline) on the number of bycaught birds per fishing event using Spearman test.

Fishing effort was calculated by multiplying the number of fishing vessels by the average number of fishing days for each season. Information on the number of active vessels and fishing days was assessed through interviews to fishermen and consultation of fishing permits given by the authorities.

For each species, total bycatch was estimated for the entire fishing fleet using known bycatch rates multiplied by fishing effort, also considering seasonal variations.

The effect of each mitigation measure on the target catch was explored using two-sample Mann-Whitney tests, comparing total catch weight between control and experimental fishing trips. Then, the bird scaring device deterrent effects on observed seabird species were evaluated. Seabird species evaluated included Northern Gannet, Cory’s Shearwater, Balearic Shearwater, all shearwaters, and Yellow-legged Gull/Lesser Black-backed Gull. To determine the number of birds interacting with the vessel, interaction behaviour was defined as whenever the birds were diving or actively searching within a range of less than 100 m from the vessel for each fishing event. The proportion of birds interacting with the vessel by the total number of birds within the 300 m range (including straight flying birds) was used to correct for abundance fluctuations among fishing trips. Differences among samples recorded during control and experimental fishing events were tested using Mann-Whitney tests. All analyses were developed in the R environment (R Core Team Reference Team2019).

Results

Seabird bycatch

Overall, 67 seabirds were bycaught from June 2015 to June 2018. Demersal longlines contributed to 88% (59 birds) of all recorded bycatch, and bottom gillnets and purse seine to 6% (four birds each). Although observation effort was not even among seasons, all but purse seines were sampled during all seasons (Figure 3). Fishing gear showed a significant effect on bycatch (Table 2), being mainly recorded in demersal longlines <12 m (88%), corresponding to 0.022 birds*10-6hooks*hours and 0.06 birds event-1 (Table 3). Despite 39% of the birds being released alive from the fishing gear, it was not possible to assess their survival and/or the level of injury. Northern Gannet was the main bycaught species (51 birds), all immature birds. Those records took place mainly during summer (53%) and spring (45%). Gannets were bycaught on demersal longlines and bottom gillnets at a bycatch rate of 0.06 (0.018 birds*10-6 hooks*hour) and 0.01 (0.05 birds*10-3hours) birds fishing event-1, respectively. Cory’s Shearwater was the second most captured species, in terms of number of individuals. All (n = 8) were caught in bottom longlines during the summer, corresponding to a bycatch rate around 0.01 birds fishing event-1 (0.003 birds*10-6 hooks*hour) and a mortality rate of 88%. Three immatures of unidentified gulls (Yellow-legged Gull/Lesser Black-backed Gull) were caught in purse seiners (Table 4). Also, two European Shags died after being caught by bottom gillnets during the winter. Other seabird species that were caught included Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo, Great Shearwater Ardenna gravis and Yellow-legged Gull.

Figure 3. Number of daily fishing trips followed by onboard observers in Ilhas Berlengas SPA from June 2015 to June 2018.

Table 2. Results of tests to evaluate the effect of fishing gear, bycaught species, distance to land, soaking time, bathymetry, setting depth, season and wind speed (following Beaufort scale) on bycatch using contingency tables and chi-square tests. Due to the low number of birds recorded in bottom gillnets and purse seines, both were excluded from the analysis. * indicates the test was statistically significant (P < 0.05) while bold values identify those categories with the largest contribution to the test in terms of Pearson residuals.

Table 3. Bycatch rate of each seabird species caught in Ilhas Berlengas SPA and surrounding waters by fishing boats with length <12 m and operating bottom gillnets or demersal longlines. Numbers are presented as total captured birds, birds per fishing trip, birds per fishing event and birds per 103 hours of soaking time. Bycatch rate as number of birds per 103 hooks and number of birds per 106 hooks per hour of soaking time are also presented for demersal longlines.

Table 4. Bycatch rate of each seabird species caught in Ilhas Berlengas SPA and surrounding waters by fishing boats with length ≥12 m and operating purse seines or bottom gillnets. Numbers are presented as total captured birds, birds per fishing trip, birds per fishing event and birds per 10-3 hours of soaking time.

Bycaught species, distance to land, soaking time, setting depth and season had a significant effect on bycatch numbers recorded aboard demersal longliners (Table 2). Bycatch mainly occurred in gear which was set at a longer distance from coast (>500 m), near the surface (≤2 m), with longer soaking times (>24 h) and during summer. Taking into consideration only events where bycatch occurred, soaking time also showed a significant positive correlation, while number of hooks and length of longline showed both a weak effect (Table 5).

Table 5. Results of tests to evaluate the effect of continuous variables (distance to land, soaking time, bathymetry, setting depth, wind speed, number of hooks and length of longline) on the number of bycaught birds per fishing event using Spearman test. Only events with observed bycatch in demersal longlines were used. * indicates the test was statistically significant (P < 0.05), and’ a weak effect.

Fishing effort

Between May 2015 and June 2018, 301 interviews were undertaken with fishermen operating bottom longlines (only boats ≤12 m), bottom gillnets and purse seines from 119 different boats in Peniche harbour. In 2015, there were 107 vessels registered in the local fishing fleet (which includes boats smaller than 9 m) operating from Peniche harbour. That same year, 31 vessels of the coastal fishing fleet with length <12 m were registered in Peniche. However, interviews were conducted on a larger number of vessels operating purse seines or bottom gillnets, indicating that some of the vessels in this fleet segment came from other fishing ports. Therefore, the number of interviewed vessels compared with data from registered fishing fleets was chosen as a proxy for the size of these fleet segments (Table 6).

Table 6. Numbers of vessels operating bottom gillnets, demersal longlines and purse seines from Peniche fishing harbour during the study period. Note that the total values do not correspond to the total number of vessels operating, as many vessels are licensed to operate more than one type of fishing gear. Both local and coastal fishing fleets include the numbers of boats registered in Peniche harbour during 2015. Surveyed vessels include the number of vessels interviewed during this study. The estimated number of vessels is presented as the minimum number for each fleet segment.

The interview data showed that during winter and autumn, the number of fishing days was significantly lower than the other half of the year (Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared = 36.22, df = 3, P < 0.05; Table 7). Fishing effort was also higher for vessels ≥12 m than <12 m (Mann-Whitney U-test = 2419, P < 0.05).

Table 7. Number of days spent fishing by vessels operating from Peniche harbour. Data collected during interviews with fishermen performed between May 2015 and June 2018. Vessel numbers are given as total number of interviewed vessels. Number of fishing days vessel-1 was calculated for each season and summed to obtain the fishing effort for the entire year. Number of performed interviews (n) is presented within brackets.

Estimated bycatch for the entire fishing fleet

Bycatch rates for each seabird species in a given season were extrapolated from the estimated annual fishing effort for the entire fishing fleet operating from Peniche harbour. Northern Gannet showed very high estimates, resulting in 14,764 ± 7,665 individuals year-1 bycaught in demersal longliners (<12 m), followed by Cory’s Shearwater in the same fishing gear at 1,634 ± 586 birds year-1. Bottom gillnets contributed with an overall capture of 186 ± 114 and 996 ± 503 birds year-1 of European Shag and Northern Gannet, respectively.

Mitigation measures trials

No seabirds were bycaught in test or control fishing events using demersal longlines or bottom gillnets. Two immature Yellow-legged/Lesser Black-backed Gulls were caught and released alive during experimental trips performed in purse seiners to test the bird scaring device. Regarding the deterrent effect of the bird scaring on seabirds, the number of the overall Yellow-legged/Lesser Black-backed Gulls counted during control fishing events (178.53 ± 180.25) was significantly higher (U = 1,585.50, P <0.05) than counts during experimental fishing events (100.76 ± 134.15; Figure 4). A similar reduction was noted in the proportion of gulls interacting with the fishing vessel during control (0.94 ± 0.13) and experimental (0.83 ± 0.27) fishing events (Table 8). Despite much lower numbers, significant differences (U = 1,322 P <0.05) were also found between Cory’s Shearwaters counted during experimental (0.18 ± 0.73) and control (0.38 ± 0.9) fishing events, though the proportions did not diverge significantly (U = 1,317.5, P = 0.05). No differences were found for counts and relative abundance of Northern Gannet, Balearic Shearwater and all shearwaters when using the scary-bird device (all P >0.05).

Figure 4. Number of Yellow-legged Gulls and Lesser black-backed Gulls counted in the vicinity of the purse seiners (<100 m) during scary-bird device paired tests. Only birds searching or diving at the fishing area were taken into consideration.

Table 8. Number of individuals counted during experimental and control fishing events to test the scary-bird deterrent effect on seabirds, presented as mean ± SD. Proportion of individuals interacting with the fishing vessel are presented within brackets. Differences among number of birds counted during control and experimental events were tested using Mann-Whitney tests. Significance was assumed for P < 0.05 and indicated with *.

Discussion

Seabird bycatch and population impacts

In general, little attention has been paid to seabird bycatch in the North-east Atlantic, which is associated with small scale fishing fleets (Pott and Wiedenfeld Reference Pott and Wiedenfeld2017). In this study, seabird bycatch was assessed for small (demersal longline and bottom gillnet) and medium-size (bottom gillnet and purse seine) fisheries operating within and in the vicinity of waters of a high priority area for seabird conservation on the Portuguese mainland. Although in most studies bycatch rates are presented with no temporal component, in our case, bycatch was likely to occur during the time that the gear was set in the water, and soaking time length was found to be related to seabird bycatch. However, standard bycatch rates were used to compare our results with previous studies. Overall, the bycatch rate of demersal longlines was very high (0.40 birds*10-3 hooks) when compared to the bycatch rate of similar gears in previous years (Portugal mainland = 0.24 birds*10-3 hooks; Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Henriques, Miodonski, Pereira, Marujo, Almeida, Barros, Andrade, Araújo, Monteiro, Vingada and Ramírez2015) or different longline gear operating in the Western Mediterranean (0.25 birds*10-3 hooks in pelagic longlines: Belda and Sánchez Reference Belda and Sánchez2001; 0.05 birds*10-3 hooks in drifting longlines: García-Barcelona et al. Reference García-Barcelona, Macías, Ortiz de Urbina, Estrada, Real and Báez2010). But it was below the bycatch rate estimated for boats operating demersal longlines in the Western Mediterranean (0.69 birds*10-3 hooks: Belda and Sánchez Reference Belda and Sánchez2001; 0.58 birds*10-3 hooks: Cortés et al. Reference Cortés, Arcos and González-Solís2017). Northern Gannet was the main species affected, corresponding to ~76% of all observed bycaught seabirds, followed by Cory’s Shearwater (~12%). Although the gannet is not listed as a species of special conservation concern, the levels of bycatch recorded in this study and reported in Portuguese waters (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Henriques, Miodonski, Pereira, Marujo, Almeida, Barros, Andrade, Araújo, Monteiro, Vingada and Ramírez2015) should not be ignored. Actually, ‘Least Concern’ species are largely affected by threats at a global level (Dias et al. Reference Dias, Martin, Pearmain, Bur, Small, Phillips, Yates, Lascelles, Garcia and Croxall2019). The Portuguese shelf waters represent an important area for at least some Northern Gannet populations during their migratory and wintering periods (Kubetzki et al. Reference Kubetzki, Garthe, Fifield, Mendel and Furness2009, Grecian et al. Reference Grecian, Williams, Votier, Bearhop, Cleasby, Grémillet, Hamer, Nuz, Lescroël, Newton, Patrick, Phillips, Wakefield and Bodey2019). More information is needed to investigate the effects of bycatch on the demographic parameters of those populations, namely on recruitment of new breeders, since our data strongly suggest that immatures are more susceptible to bycatch than adult birds.

Cory’s Shearwater was also bycaught in high numbers and annual estimates represent ~80% of the Berlengas breeding population. The majority of individuals using this area are local breeders and prospectors (Paiva et al. Reference Paiva, Geraldes, Ramírez, Meirinho, Garthe and Ramos2010, Catry et al. Reference Catry, Dias, Phillips and Granadeiro2011, Avalos et al. Reference Avalos, Ramos, Soares, Ceia, Fagundes, Gouveia, Menezes and Paiva2017, Reyes-González et al. Reference Reyes-González, Zajková, Morera-Pujol, De Felipe, Militão, Dell’Ariccia, Ramos, Igual, Arcos and González-Solis2017) and the small Berlengas population is estimated at around 800–975 breeding pairs (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Abreu, Bores, Fagundes, Alonso and Andrade2020). Although bycatch rate may be overestimated due to variability within each season, the annual numbers should be viewed as rough estimates pointing towards a strong effect on the Cory’s Shearwater population breeding in the Berlengas archipelago. Recent data point to a reduction in the main breeding population of this archipelago, located on Farilhão Islet, where a negative trend was recorded during the last 15 years (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Abreu, Bores, Fagundes, Alonso and Andrade2020) and high adult mortality levels may explain such a decline (authors unpubl. data). This negative trend might be remedied by the improvement in nesting habitat quality from artificial nest construction over the last 30 years. Some additional bycatch may derive from other fishing gear, since fishermen operating bottom gillnets have also reported catching Cory’s Shearwaters (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Henriques, Miodonski, Pereira, Marujo, Almeida, Barros, Andrade, Araújo, Monteiro, Vingada and Ramírez2015, Reference Oliveira, Abreu, Bores, Fagundes, Alonso and Andrade2020).

For some seabird populations with very low numbers and restricted home ranges, such as European Shags breeding in Berlengas, avoiding bycatch-driven mortality is imperative. With a breeding population estimated at only 75 pairs (Silva et al. Reference Silva, Luís and Oliveira2017), even small bycatch levels may pose a serious threat. Unlike other seabird species, European Shags have low survival rates in the first stages of life (Velando and Freire Reference Velando and Freire2002), resulting in a small proportion of non-breeding birds occurring in the vicinity of the breeding colonies. Hence, small variations in mortality rates may quickly drive the population to extinction (Velando and Freire Reference Velando and Freire2002). A small number of studies have recorded bycatch of European Shag (Žydelis et al. Reference Žydelis, Bellebaum, Österblom, Vetemaa, Schirmeister, Stipniece, Dagys, van Eerden and Garthe2009), although evidence of bycatch in set nets have been reported (Velando and Freire Reference Velando and Freire2002). An underestimate of bycatch impacts may be due to the low effort in monitoring small-scale fishing fleets at a European level (Pott and Wiedenfeld Reference Pott and Wiedenfeld2017).

Factors affecting seabird bycatch

The low number of bycatch events involving purse seines and bottom gillnets prevented exploration of the factors affecting seabird bycatch caused by them. This analysis was only possible for demersal longlines. Unlike many other studies exploring seabird bycatch on longlines (e.g. Belda and Sánchez Reference Belda and Sánchez2001, Gilman Reference Gilman2011, Cortés et al. Reference Cortés, Arcos and González-Solís2017), in our case, bycatch occurred only when the gear was soaked in the water, with no birds being caught during setting or hauling.

Regarding the duration of soaking time and setting depth, birds were mainly caught while gear was left in the water for longer than 24 h or near the surface (≤2 m). This may be indirectly related to the type of bait. Crab species used as bait are non-typical prey of Cory’s Shearwater and Northern Gannet, but smaller non-target fish species like Atlantic chub mackerel or blue jack mackerel may be attracted or caught before the target species, attracting seabirds to the longline. Fish species caught on the hooks are then more accessible to seabirds in shallow waters. National legislation is quite vague in terms of demersal longline technical details. However, set gears are not allowed to be in the water for longer than 24 hours, with some exceptions, which should mitigate bycatch. Even so, improving gear specification through national legislation is recommended, in terms of gear position in the water column.

Season was also an important factor affecting seabird bycatch. As reported in the Western Mediterranean area (Belda and Sánchez Reference Belda and Sánchez2001, García-Barcelona et al. Reference García-Barcelona, Macías, Ortiz de Urbina, Estrada, Real and Báez2010, Laneri et al. Reference Laneri, Louzao, Martínez-Abraín, Arcos, Belda, Guallart, Sánchez, Giménez, Maestre and Oro2010, Cortés et al. Reference Cortés, Arcos and González-Solís2017), bycatch tends to occur mainly during spring and summer, corresponding to the periods with higher fishing effort in Ilhas Berlengas SPA. Breeding Cory’s Shearwaters are known to use the waters around Berlengas more intensively during the first weeks after chick hatching (Paiva et al. Reference Paiva, Geraldes, Ramírez, Meirinho, Garthe and Ramos2010) putting them at higher risk of being caught, as confirmed by our data. Breeding adults search for food around breeding colonies during the day to feed chicks later during the night. Regarding Northern Gannets, only immature birds (of different ages) were caught during our study. Non-breeding birds use Portuguese waters all year round (Meirinho et al. Reference Meirinho, Barros, Oliveira, Catry, Lecoq, Paiva, Geraldes, Granadeiro, Ramírez and Andrade2014) and young birds are usually more dependent on the easiest sources of food, such as fishery discards or bait, compared to adult birds (Calado et al. in press).

The fleets studied here operate in coastal waters, fishing no further than 10 km from the shoreline (Berlenga Island is also considered as shoreline serving as a fishing harbour). Within this band, bycatch tends to occur beyond 500 m, where seabirds search for food avoiding shorter distances from the shoreline. However, bathymetry does not show an effect on bycatch, at least in the case of demersal longlines. One possible explanation is that at a fine scale, the study area is composed of several productive but small sea banks. Such areas are intensively explored by local fishermen using longlines that are set beyond the banks. Also, the number of hooks and length of longlines showed a small effect on bycatch though not statistically significant as shown in other studies (Cortés et al. Reference Cortés, Arcos and González-Solís2017).

Efficacy of mitigation measures on reducing seabird bycatch and their economic impact

Since no seabird mortality related to bycatch was recorded during the trials, the efficacy of the mitigation measures was evaluated in terms of economic impact and reduced attraction of birds to the fishing area. In fact, a great number of fishing trips are needed to obtain accurate estimates of seabird bycatch (Oliveira et al. Reference Oliveira, Henriques, Miodonski, Pereira, Marujo, Almeida, Barros, Andrade, Araújo, Monteiro, Vingada and Ramírez2015). Trials took place when seabird abundance was higher and/or bycatch was more likely to occur in order to overcome the low number of foreseen trials, but with little success.

The cost of using high contrast panels was 0.34–0.56 € per meter of gillnet, representing an increment of 26–40% on the total gear cost, but differences were found in terms of mean catch weight between test and control events. However, it should be recognized that if these modifications were implemented on a large scale, the unit price for modifying gillnets would likely decrease. Installation time could also be reduced if nets were already produced with integrated panels instead of being retrofitted. Despite the low number of trials, we found similar results to a study developed in the Baltic Sea in terms of the number of catches where the panels also showed no effect on seabird bycatch (Field et al. Reference Field, Crawford, Enever, Linkowski, Martin, Mork and Oppel2019). Previous studies showed a potential reduction in seabird bycatch by increasing gillnet visibility underwater (Martin and Crawford Reference Martin and Crawford2015, Mangel et al. Reference Mangel, Wang, Alfaro-, Pingo, Jimenez, Swimmer and Godley2018) and more trials are required to clarify the effectiveness of high contrast panels to reduce seabird bycatch in Iberian Atlantic waters. Also, some adaptations may be incorporated to solve the limitations pointed out by fishermen when operating gillnets fitted with high contrast panels.

Although high bycatch levels in demersal longlines were found in this study, results of trials with black hooks were inconclusive. The cost of using black hooks represented a considerable increase (70–209%) in production cost, and both captains found black hooks ineffective in reducing seabird bycatch, costly, and lasted less than the traditional hooks. Again, the cost of such modifications may be greatly reduced if implemented on a larger scale. The amount of bycatch during the trials was very low and may not reflect the real situation with this fishing technique. Several approaches have been tested around the world to reduce seabird bycatch in longlines. Night setting showed a greater potential to reduce seabird bycatch in small scale fisheries operating in the Western Mediterranean when compared to tori lines, weighted lines or artificial bait (Cortés and González-Solís Reference Cortés and González-Solís2018). In our case, seabird bycatch occurred while longlines were soaked in the water, preventing the successful use of tori lines or other devices, like underwater setting and line shooters installed in the fishing boats and tested by Løkkeborg (Reference Løkkeborg2003). Limiting the soaking time to the night period should be tested in future trials as well as the use of deterrent devices set on the longline buoys.

The bird scaring device showed great potential to reduce seabird bycatch in purse seiners. The cost represented less than 5% of a single day’s landings, and no differences were found in terms of mean catch weight between test and control events. The long durability together with the lower cost of the bird scaring device increases its acceptance by local fishermen. Moreover, its high effectiveness as a gull deterrent is a major advantage from the point of view of the fishermen. Despite the low effectiveness of bird scaring devices as bird deterrents at land-based sites like landfills (Cook et al. Reference Cook, Rushton, Allan and Baxter2008), urban areas (Belant et al. Reference Belant, Woronecki, Dolbeer, Thomas, Belarttn, Wororzeckin, Dolbeern and Seamarls2016) and fruit crops (Steensma et al. Reference Steensma, Lindell, Leigh, Burrows, Wieferich and Zwamborn2016), to the best of our knowledge, no previous study has tested this device at sea, where bird species may have different behaviours and/or ecological strategies. However, the effect of the bird scaring device at sea on species other than gulls remains unclear. Even if a positive effect was noted on Cory’s Shearwater, the low numbers of birds counted during both test and control events call for more research. Further trials should include sites and seasonal periods with a higher abundance of seabird species of conservation concern.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the Portuguese Maritime Authority and Peniche Port Authority for all receptivity and licences needed to develop this study. To both fishermen associations of Peniche (Cooperativa dos Armadores de Pesca Artesanal CRL – CAPA and Cooperativa Da Pesca Geral Do Centro, C.R.L - Opcentro) who make the first contact with local fishermen. To all involved fishermen, who welcomed us on to their boats or answered our questionnaires and interviews. To Docapesca for sharing landings data. To all volunteers for their great help, namely Cláudio Bicho, Filipa Pinto, Joana Bores, Rita Matos, Tânia Nascimento e Valter Quadros. We are also grateful to Edward Adlard for his revision of the manuscript regarding English language and grammar and to the two reviewers who help to improve greatly the final text. This study was developed under the frames of the project LIFE+ Berlengas (LIFE13/NAT/PT/000458) and co-funded by the European Commission, and by the Portuguese Government through the “Fundo Ambiental”.