Introduction

Citizen science is when people contribute observations or efforts to a scientific enterprise (Bonney Reference Bonney1996). Some benefits of conservation programmes that include citizen participation are the capacity for research at broadly ambitious spatio-temporal scales and the generation of ecological knowledge and conservation consciousness (Tulloch et al. Reference Tulloch, Possingham, Joseph, Szabo and Martin2013). Citizen scientists can cover extensive areas at the same time, which would otherwise be almost impossible for a group of scientists. For this reason, citizen scientists can be considered as the world’s largest research team (Irwin Reference Irwin1995). The amount of data collected is not always the most important benefit of citizen science, as involvement of society in a certain conservation cause can be achieved and can have greater and long-standing impacts (Tulloch et al. Reference Tulloch, Possingham, Joseph, Szabo and Martin2013). Although citizen science can produce huge amounts of data for extended periods of time or simultaneously in different geographical areas, limitations that might affect data quality should be considered (Szabo et al. Reference Szabo, Fuller and Possingham2012). Sampling bias among locations and analytical challenges for untrained volunteers might impact on collected data (McKinley et al. Reference McKinley, Rushing, Ballard, Bonney, Brown, Cook-Patton, Evans, French, Parrish, Phillips, Ryan, Shanley, Shirk, Stepenuck, Weltzin, Wiggins, Boyle, Briggs, Chapin, Hewitt, Preuss and Soukup2017, Thornhill et al. Reference Thornhill, Loiselle, Lind and Ophof2019).

The Yellow Cardinal, Gubernatrix cristata (Vieillot 1817), is a globally threatened passerine (BirdLife International 2018a) from southern South America that could benefit from a citizen science programme. It is a sexually dimorphic species, with males bearing a strikingly yellow plumage and a black throat patch, while females are more greyish (Ridgely and Tudor Reference Ridgely and Tudor1997). It inhabits open woodlands, savannas, scrub and shrubby steppes characteristic of the ‘Espinal’ ecoregion, represented mainly by the presence of thorny trees and shrubs (BirdLife International 2018b). The ‘Espinal’ ecoregion presents, in almost all its extent, patches of forest interspersed with pastures, including woodlands and more open savanna-like landscapes (Cabrera Reference Cabrera1976). In the past, the Yellow Cardinal was commonly observed in the thorny shrublands of Argentina, Uruguay and the state of Rio Grande do Sul in Brazil (Ridgely and Tudor Reference Ridgely and Tudor1997). Doubtful records of Yellow Cardinals in Paraguay are also found in early literature (Ridgely and Tudor Reference Ridgely and Tudor1989, Collar et al. Reference Collar, Gonzaga, Krabbe, Madroño Nieto, Naranjo, Parker and Wege1992). Currently, the occurrence of the species in Paraguay is considered insufficiently documented (del Castillo and Clay Reference del Castillo and Clay2004) and observed individuals are suspected escapees from captivity (Hayes Reference Hayes1995). Uruguay hosts approximately 300 individuals (Aspiroz et al. 2012), while < 50 individuals were observed in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (Beier et al. Reference Beier, Repenning, da Silveira Pereira, Pereira and Suertegaray Fontana2017). At present, the largest natural populations of Yellow Cardinals are found in Argentina (BirdLife International 2018b) but its distribution is believed to be highly discontinuous, with few areas where the species is present separated by areas with scarce or no records (Zelaya and Bertonatti Reference Zelaya and Bertonatti1995). The main causes of global decline of the Yellow Cardinal are habitat loss due to wood extraction and agriculture, as well as the capture of individuals for the illegal cage bird market (Ortiz Reference Ortiz and Aceñolaza2008). Due to habitat loss and population decline it is categorized as globally ‘Endangered’ (BirdLife International 2018a), endangered in Argentina (López-Lanús et al. Reference López-Lanús, Grilli, Di Giacomo, Coconier and Banchs2008) and Uruguay (Aspiroz et al. 2012, Azpiroz Reference Azpiroz, Azpiroz, Jimenez and Alfaro2017), and critically endangered in Brazil (Martins-Ferreira et al. 2013).

To improve our knowledge of Yellow Cardinal trends, efforts have been taken to study remaining populations in recent years. Based on published records, Reales et al. (Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019) constructed a distribution map of the species and found a reduction in the original distribution. Previous work on genetic (Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Tiedemann, Reboreda, Segura, Tittarelli and Mahler2017) and song (Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Reboreda and Mahler2016) differentiation of isolated populations supported the existence of three management units (Moritz Reference Moritz1994) in Argentina. The geographical variation in vocalisations could enhance detection, especially when using playback. The Yellow Cardinal is also known to be highly territorial, males reacting aggressively to the presence of other males (Collar et al. Reference Collar, Gonzaga, Krabbe, Madroño Nieto, Naranjo, Parker and Wege1992). This behaviour is usually more intense during the breeding season, which occurs in the austral spring between October and December (Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Reboreda and Mahler2015).

Although a database with presence data points of Yellow Cardinals from 1995 to 2018 has been assembled (Reales et al. Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019), there is no information on the presence of the species in several regions with historical presence and/or suitable habitat. Moreover, extraction of individuals for the cage bird market can decrease population size rapidly until local extinctions, as frequently observed in recent years (López-Lanús et al. Reference López-Lanús, Ibáñez, Velazco and Bertonatti2016). Therefore, an updated and comprehensive evaluation of the species’ distribution is required. Here we report the results of the first coordinated surveys of Yellow Cardinals based on a citizen science programme in Argentina. The aims of this study were to update the distribution map of the Yellow Cardinal, identify important areas for its conservation, provide information about understudied areas, and encourage the creation of new conservation groups in areas where the species is still present. We also discuss further long-term strategies that could provide important tools for conservation and management actions.

Methods

Bibliographic review

A multi-source compilation of historic Yellow Cardinal distribution data in Argentina was created including records from 1880 to 1998. We sought information in all available publications through an exhaustive bibliographic search (Appendix S1 in the online supplementary material), in free databases (eBird.org, Global Biodiversity Information Facility – gbif.org, EcoRegistros.org, and Banco de Registros de Cardenal Amarillo, handled by the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development of Argentina), as well as from specimens deposited in museums (Appendix S2). As these sources largely coincide with those of Reales et al. (Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019), to avoid duplication, we took presence points independently of that study. Based on this information, we constructed a database.

Present surveys

To compare present versus past distribution, all areas of the country with historical records of Yellow Cardinals were surveyed during 2015, 2016 and 2017. This included 12 provinces of Argentina: Entre Ríos, Corrientes, Santa Fe, Santiago del Estero, Córdoba, La Rioja, San Luis, La Pampa, Mendoza, Neuquén, Río Negro, and Buenos Aires. Surveys were conducted every year from early-mid September to early October, considering the pre-breeding season as the most appropriate time to conduct the survey since cardinals begin to defend their territories and are easier to spot (Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Reboreda and Mahler2015). In addition, we minimised the risk that nests with chicks become unattended because of the disturbance of our survey. Most surveys were performed from 06h30 to 10h30 local time in order to concentrate efforts during the presumed peak activity time of cardinals. Participants’ recruitment was coordinated by the non-governmental organization Aves Argentinas. Surveys were advertised through social networks multiple times in June–July, before the pre-breeding period that starts in September. An e-mail was also sent out to all members of Aves Argentinas requesting volunteers to follow a link and complete a form. Registration forms allowed us to determine the localities of each volunteer and possible sampling sites. It also allowed people from the same area to organise sampling effort. Based on the bibliographic review and on current habitat availability, we proposed survey areas to volunteers. Some of these areas had historical occurrences and others had no records, but suitable habitat. With this information, participants freely determined their survey areas based on distance and accessibility.

Survey design

Observers recorded the number of identified Yellow Cardinals. Survey data were compiled by Aves Argentinas and the Laboratory of Ecology and Animal Behavior of the University of Buenos Aires. Since the species does not present particular identification challenges, we included records from 143 observers, including amateur birdwatchers, professional ornithologists, educators and rangers of protected areas. A specific methodology was recommended to ensure consistency of results among observers. The search protocol included playback to maximise the chance of detecting Yellow Cardinals. Given that previous studies have found that there are different dialects among Yellow Cardinal populations (Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Reboreda and Mahler2016), participants were provided with recordings of a male song obtained near their survey area. An individual’s detectability increases with its response to conspecific playbacks emitted by a digital device connected to a speaker or using a mobile phone (Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Reboreda and Mahler2015). Within the areas determined for surveys, participants randomly selected points separated by at least 300 m and played the song for 90 seconds. The separation of 300 m between survey sites was set to avoid recording the same bird at two different points, based on information on mean territory size (2.16 ± 0.88 ha) and average distance between territories (Domínguez Reference Domínguez2015). For the 2017 survey, an app was developed using Survey123 (an application of ArcGIS; ESRI 2011) in order to create a digital survey (available at https://bit.ly/2v6tAJC) accessible from a mobile application for phones and tablets to simplify data collection and subsequent analyses. Geographic coordinates of all located cardinals were recorded using a handheld GPS device or the GPS included on mobile phones.

Participants were encouraged to complement the survey with an awareness campaign in their survey area aimed at decreasing illegal capture of Yellow Cardinals. This activity was supported by Aves Argentinas who provided informative material including 300 stickers and 500 posters. There were also informative workshops in 12 elementary schools.

Data analysis

We recorded the total number of observed Yellow Cardinals. Sampling success was calculated as the number of survey points with positive records divided by the total number of points sampled, expressed as a percentage. We compared sampling success and number of surveyors across years as a measure of detection rate considering the number of sites visited.

We used gap analysis (Scott et al. Reference Scott, Davis, Csuti, Noss, Butterfield, Groves, Anderson, Caicco, D'Erchia, Edwards, Ulliman and Wright1993) to study the degree of protection of cardinals in the current protected areas system of Argentina and to compare the results of recent surveys of Yellow Cardinals with the current extension of ‘Espinal’ ecoregion. A shapefile including 356 protected areas was constructed with information obtained from the World Database on Protected Areas (IUCN, UNEP-WCMC 2018). From the World Database on Protected Areas we retained only those protected areas that fell into IUCN management categories I to VI (Ia: Strict Nature Reserve; Ib: Wilderness Area; II: National Park; III: Natural Monument or Feature; IV: Habitat/Species Management Area; V: Protected Landscape/Seascape; VI: Protected area with sustainable use of natural resources; Dudley Reference Dudley2008). We added 19 protected areas unlisted by IUCN because they lacked available or implemented management plans, but that were of local importance (Table S1). These included some biosphere reserves, Ramsar sites and private reserves. An additional private protected area called Isleta Linda, that was not in the local database was roughly mapped based on the description of its limits according to Fandiño et al. (Reference Fandiño, Leiva, Pautasso, Luna and Manassero2015). Records of Yellow Cardinals within protected areas were mapped. We also assessed whether the current range of Yellow Cardinals matched that of the ‘Espinal’ ecoregion. We used the most recent layer available at Fundación ProYungas (shapefile accessible from https://bit.ly/2OmqxWH). This layer is based on the latest land use assessment (Brown and Pacheco Reference Brown, Pacheco, Brown, Martínez Ortiz, Acerbi and Corchera2006). With the purpose of making the comparison easy to visualise and since this ecoregion is known to have suffered a severe transformation in the last years, we also mapped historical records against a layer describing the ancient ‘Espinal’ (according to Burkart et al. Reference Burkart, Bárbaro, Sánchez and Gómez1999).

Results

Historical distribution

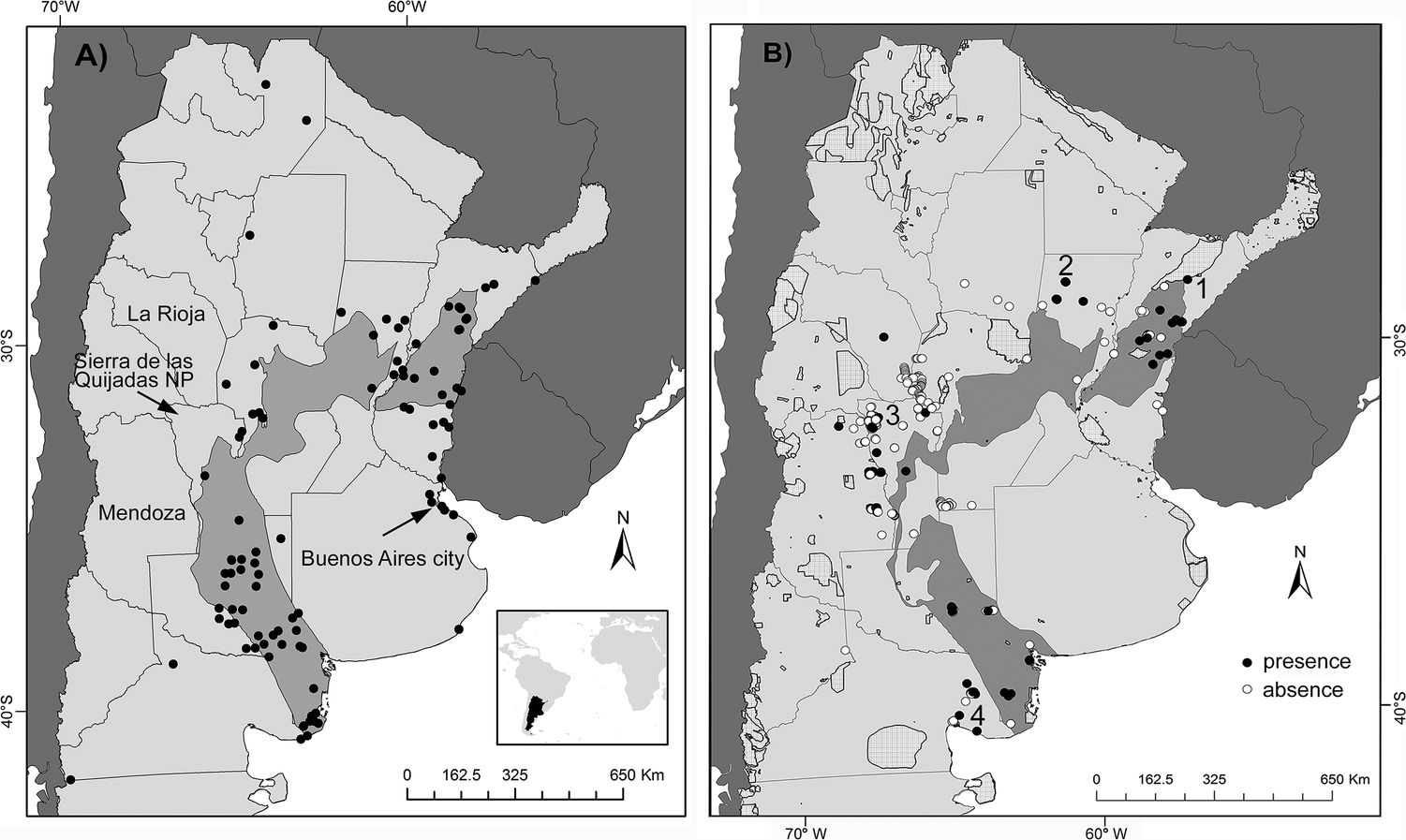

From 1880 to 1998, we documented 130 points of occurrence of Yellow Cardinals in Argentina representing the known historical distribution of the species (Figure 1a). Outside the polygon describing the ‘Espinal’ and considering a buffer of 60 km, we only found 18 points with presence of cardinals, which corresponds to 14% of historical records.

Figure 1. Location of the study area. A) Black dots denote historic records (1880 to 1998) of Yellow Cardinals in Argentina. The original range of ‘Espinal’ ecoregion according to Burkart et al. (Reference Burkart, Bárbaro, Sánchez and Gómez1999) is shown in dark grey. Two provinces, La Rioja and Mendoza, and metropolitan Buenos Aires, as well as Sierra de las Quijadas National Park (NP) are indicated. B) Dots represent sites surveyed during 2015, 2016 and 2017. Black dots are sites where cardinals were registered, white dots are sites where yellow cardinals were not found during surveys. The current range of ‘Espinal’ ecoregion according to Brown and Pacheco (Reference Brown, Pacheco, Brown, Martínez Ortiz, Acerbi and Corchera2006) is shown in dark grey. Polygons represent protected areas, with numbers denoting presence of Yellow Cardinals in Iberá Nature Reserve (1), Isleta Linda Private Reserve (2), Sierra de las Quijadas National Park (3), and Caleta de los Loros Reserve (4).

Current distribution

The surveys included 644 points (Table 1) and covered most of the historical distribution of Yellow Cardinals (Figure 1b). The sampling success (percentage of positive records) was 10%, 13% and 33.5% for 2015, 2016 and 2017, respectively. The numbers of individuals recorded for these years were 39, 74 and 108, respectively (Table 1) with a discontinuous distribution within the ‘Espinal’ ecoregion (Figure 1b). Particularly interesting records of new areas of occurrence were obtained in La Rioja province and in Sierra de las Quijadas National Park, where the species had been considered absent within the protected area.

Table 1. The total number of citizen scientists and sampling success per year for the Yellow Cardinal in Argentina. Sampling success was calculated as the number of sites with positive records divided by total number of points sampled, expressed as a percentage.

Many records (69%) were found outside of the described limit of the current ‘Espinal’ distribution (Figure 1b). The level of overlap of Yellow Cardinals with protected areas was very small and 78% of individuals were recorded outside protected areas. Only four protected areas contained records of Yellow Cardinals (Figure 1b): Iberá Nature Reserve and Isleta Linda Private Reserve in the north-eastern part of its distribution, Sierra de las Quijadas National Park in the central-western part, and Caleta de los Loros Reserve in the south (Figure 1b).

Discussion

To promote conservation actions for threatened species it is essential to have reliable and updated information about their distribution (Grenyer et al. Reference Grenyer, Orme, Jackson, Thomas, Davies, Davies, Jones, Olson, Ridgely, Rasmussen, Ding, Bennett, Blackburn, Gaston, Gittleman and Owens2006). This study represents the most geographically comprehensive survey of Yellow Cardinals in Argentina and shows that the species is currently absent in areas with suitable habitat, but present in formerly unknown areas within drier ecoregions.

Historical distribution

The historical distribution of Yellow Cardinal in Argentina (Figure 1a) matches almost perfectly the area formerly occupied by ‘Espinal’ vegetation. There are a few exceptions, for instance the records in valleys along the Andes ridge in central Patagonia, in north-western Argentina, and in Buenos Aires metropolitan area. These isolated records might have been of captive origin but considering the more widespread distribution of the species in the past, it is not inconceivable that some of these records were in fact marginal natural populations. This is especially true in Buenos Aires area where the ‘Talar’ forest has been described as a low diversity type of ‘Espinal’ (Haene Reference Haene, Mérida and Athor2006). These forests are also dominated by thorny trees, mainly Celtis tala and Scutia buxifolia, and are found in narrow belts along riversides (Cabrera Reference Cabrera1976).

Current distribution

During the three surveys, 221 Yellow Cardinals were registered in Argentina. Since the survey was open to the general public, we did not know in advance whether the sampling effort was going to be comparable between years. However, we found that the smallest sampling effort (number of participants per number of sites surveyed) in the 2017 survey achieved the highest sampling success (Table 1). This could be partly explained by the participants developing a search image and better recognizing appropriate sites for the Yellow Cardinal. Also, surveys were extended to Mendoza province, where cardinals were sighted for the first time.

We obtained occurrence records in new areas compared to the historical distribution (Figure 1b). Reinforcing published results (Sosa et al. Reference Sosa, Martín and Zarco2011, Reales et al. Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019), we found Yellow Cardinals in areas west of the original distribution. The presence of cardinals in Sierra de las Quijadas National Park in San Luis province was surprising, since there are no historical records of the species, probably because of the lack of surveys in the national park. Besides those new localities, the Yellow Cardinal has disappeared from a good part of its historical distribution. Although records were always more scattered in the central part of the distribution compared to the margins (Reales et al. Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019), it used to harbour populations. Nevertheless, in spite of the efforts, no Yellow Cardinals were sighted. This coincides with the lower density registered in this region by Reales et al. (Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019). Since several sites were surveyed, we are confident that the lack of records is a consequence of true absence and not of the sampling design.

The recent sightings published in this study confirm that Yellow Cardinal distribution is highly fragmented (Zelaya and Bertonatti Reference Zelaya and Bertonatti1995; Figure 1b). The three major occupied areas coincide with the management units previously suggested by population structure analyses (Domínguez et al. Reference Domínguez, Reboreda and Mahler2016, Reference Domínguez, Tiedemann, Reboreda, Segura, Tittarelli and Mahler2017). The presence of cardinals in between these regions is scarce (Reales et al. Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019).

Land transformation in the ‘Espinal’ ecoregion

The ‘Espinal’ ecoregion has been underestimated for its biodiversity value with very few protected areas within it (Figure 1b). Even though the Yellow Cardinal was considered a typical species of the ‘Espinal’ ecoregion, we found that almost 70% of presence points were located in other habitat types, the drier ‘Monte’ and ‘Chaco’ ecoregions (Cabrera Reference Cabrera1976). In a more exhaustive study carried out in southern Buenos Aires Province, Yellow Cardinals were also found in ‘Monte’ ecoregion (Marateo et al. Reference Marateo, Archuby, Piantanida, Sotelo and Segura2018). On the one hand, Yellow Cardinals might have always used these drier regions, which we partially included in the 60 km buffer of the historical distribution. On the other hand, presence in these ecoregions might have increased because of the decrease of the original habitat due to major changes in land use. In the past, the ‘Espinal’ ecoregion constituted a forest ring of 24,000,000 ha that surrounded the Pampean region (Cabrera Reference Cabrera1976) and represented more than 8% of the area of Argentina (Brown and Pacheco Reference Brown, Pacheco, Brown, Martínez Ortiz, Acerbi and Corchera2006). Due to the advance of the agricultural frontier and the extraction of firewood, ‘Espinal’ forests have diminished considerably (Arturi Reference Arturi, Brown, Ortiz, Acerbi and Corcuera2005). In 2005, a loss of around 40% of this area was estimated (Brown and Pacheco Reference Brown, Pacheco, Brown, Martínez Ortiz, Acerbi and Corchera2006, Guida-Johnson and Zuleta Reference Guida-Johnson and Zuleta2013) with more than 9,000,000 hectares transformed. The Yellow Cardinal is absent in these modified areas (Reales et al. Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019), thus leading to fragmented distribution.

Protected areas

The gap analysis showed only four protected areas with Yellow Cardinal presence. These areas lack connectivity: two (Iberá and Isleta Linda) are located in the east, Sierra de las Quijadas is in the west and Caleta de los Loros is in the south. Yellow Cardinals were detected with relatively low sampling effort in the four protected areas, implying that they may contain many individuals, irrespective of their size (varying from 9,000 ha in Caleta de los Loros to 1,200,000 ha in Iberá; SIB 2018) and level of protection (from private reserves with multiple use to a national park). Yellow Cardinals were recently recorded in three additional protected areas (Reales et al. Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019). We surveyed one of these areas (Quebracho de la Legua in San Luis Province) but found Yellow Cardinals only in its surroundings, showing the importance of habitat continuity to allow individual movements. Even though protected areas are of great conservation value, we identified many unprotected regions important for the conservation of the species (Figure 1b), some of which are Important Bird Areas (IBAs; Reales et al. Reference Reales, Sarquis, Daradanelli and Lammertink2019). Since the legal status of IBAs is very variable, we suggest the creation of additional protected areas in sites of Yellow Cardinals occurrence. This can be done by establishing private reserves in collaboration with landowners or by increasing the level of protection of specific IBAs, crucial for the long-term conservation of the species.

Citizen science

As shown in this study, citizen science can make a useful contribution to conservation. Public engagement, scientific learning, socialization and awareness-raising are often important results from citizen science programmes (Conrad and Hilchey Reference Conrad and Hilchey2011, Lowry and Fienen Reference Lowry and Fienen2013, Tulloch et al. Reference Tulloch, Possingham, Joseph, Szabo and Martin2013). Nowadays, internet and GIS-enabled web applications allow surveyors to collect large amounts of location-based ecological data and submit them electronically to centralised databases (Dickinson et al. Reference Dickinson, Shirk, Bonter, Bonney, Crain, Martin, Phillips and Purcell2012), simplifying data collection and subsequent analyses. As a result of a collaborative planned sampling, we were able to survey for three consecutive years locations with historical presence of Yellow Cardinals in the country that hosts most of its remaining populations. The 143 citizens not only searched for the species in extensive areas, but also organised dissemination activities with educational material that was provided. As another proof of the success of our citizen science programme, new Yellow Cardinal monitoring groups were organised in the areas where the species is still present.

Implications for conservation

We seek to continue our annual surveys in order to maintain an extensive Yellow Cardinal survey dataset that will allow more accurate maps to be compiled and address many management questions. An accurate current range map is of huge importance as a baseline for future range changes in relation to climate change or to more localised environmental or anthropogenic impacts. Illegal trafficking jeopardises the survival of Yellow Cardinal populations. This situation implies a strong concern about local population viability, so monitoring is recommended. Monitoring the populations recorded in this study will demand collaboration among stakeholders, including scientists, civil society, politicians, and the private sector. Furthermore, our gap analysis identified potential regions for the creation of protected areas and can form the basis for sustained discussions on priorities for the conservation of the Yellow Cardinal.

Future studies may use the information generated by these Yellow Cardinal surveys to better analyse the role of habitat transformation and apply ecological niche models to assess the potential geographic distribution at present. The outcomes of those models could serve to guide future surveys to unveil other Yellow Cardinal populations in Argentina.

Supplementary Materials

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0959270920000155.

Acknowledgements

We thank participating institutions for logistical support and the more than 100 citizen scientists for conducting the surveys, including the Aves Argentinas team, the COA (Birdwatching Clubs) of Merlo, Chilecito, Barranquero, Valle Conesa, Cuña Boscosa, Lobería, Kuis and Necochea and the NGOs CEyDAS and CAASER, as well as park rangers and brigade members of Sierra de las Quijadas National Park. We thank R. Fariña and I. Pereda for their invaluable help during the surveys and their commitment to the Yellow Cardinal Project and R. Medina for her advices on data analysis. J. C. Reboreda and I. Roesler made valuable comments on a previous version of the manuscript. We also thank the museums visited for giving us access to their collections. MD and BM are CONICET researchers. Funding was provided by the Environmental Protection Agency of Buenos Aires City and Banco Galicia (FOCA). We obtained local support from the National Park Administration and Sierra de las Quijadas National Park, Wildlife Department - Direction of Renewable Resources of Mendoza Province, Azara Foundation, Behavioral Ecology Research Group (IADIZA-CONICET), Alvear City Government, Mendoza Province, and the Biodiversity Program of “Ministerio de Medio Ambiente, Campo y Producción” of San Luis Province.