Introduction

Vultures have been declining at an alarming rate worldwide due to human-related factors, including intentional and secondary poisoning, electrocution and decrease in food supplies (Ogada et al. Reference Ogada, Keesing and Virani2012, Reference Ogada, Shaw, Beyers, Buij, Murn, Thiollay, Beale, Holdo, Pomeroy, Baker, Krüger, Botha, Virani, Monadjem and Sinclair2016). In consequence, vultures are now the avian functional guild at a higher risk of extinction in the world (Buechley and Şekercioğlu Reference Buechley and Şekercioğlu2016).

The collapse of vulture populations due to the ingestion of dietary toxins, including the veterinary drug diclofenac and poisons used against mammalian predators, may heighten the likelihood of dangerous pathogenic agents spreading from carcases, with serious consequences to human and livestock health, and the economy (Markandya et al. Reference Markandya, Taylor, Longo, Murty, Murty and Dhavala2008, Buechley and Şekercioğlu Reference Buechley and Şekercioğlu2016). Also, due to the lack of competition from vultures, opportunistic facultative scavengers may increase in numbers, a fact that, like mesopredator release resulting from the eradication of apex predators, may result in the undesirable increase in predation upon several species (Buechley and Şekercioğlu Reference Buechley and Şekercioğlu2016).

Extensive livestock herding is a staple food source for healthy vulture populations (Olea and Mateo-Tomás Reference Olea and Mateo-Tomás2009) and conversely, its abandonment is a major cause of food shortage, with a negative impact on their survival and productivity (Margalida and Colomer Reference Margalida and Colomer2012, Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Oliva-Vidal, Llamas and Colomer2018). In Europe, this situation worsened due to sanitary restrictions to control the spread of the bovine spongiform encephalopathy and the associated risk to public health in the late 1990s, which forced the removal of most livestock carcases from the open, with a serious decrease of food availability for vultures (Donázar et al. Reference Donázar, Margalida, Carrete and Sánchez-Zapata2009, Margalida et al. Reference Margalida, Donázar, Carrete and Sánchez-Zapata2010). More recently, new regulations aimed at reducing the prevalence of bovine tuberculosis in wild ungulates through complete removal of the leftovers from hunted animals came into force in parts of Spain, causing further limitation of the food supply for vultures (Margalida and Moleón Reference Margalida and Moleón2016).

Besides the impacts of poisoning and food shortage, the risk of raptor mortality by collision with wind farms, although highly variable, may be high in some species, in sensitive locations and particular individual turbines; besides, wind farms may also cause the loss of bird habitats, either through the occupation of critical areas of the home range or by causing avoidance of the wind farm area (Sánchez-Zapata et al. Reference Sánchez-Zapata, Clavero, Carrete, DeVault, Hermoso, Losada, Polo, Sánchez-Navarro, Pérez-García, Botella, Ibáñez and Donázar2016).

Vultures have sharply declined in Africa, including West Africa (Thiollay Reference Thiollay2006, Botha et al. Reference Botha, Ogada and Virani2012, Ogada et al. Reference Ogada, Shaw, Beyers, Buij, Murn, Thiollay, Beale, Holdo, Pomeroy, Baker, Krüger, Botha, Virani, Monadjem and Sinclair2016, Safford et al. Reference Safford, Andevski, Botha, Bowden, Crockford, Garbett, Margalida, Ramírez, Shobrak, Tavares and Williams2019). Consequently, most African vulture species have been recently uplisted to ‘Endangered’ and ‘Critically Endangered’ status (IUCN 2018). Also, a Multi-species Action Plan to Conserve African-Eurasian Vultures (Vulture MsAP) was recently adopted by the CMS (Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals) (Botha et al. Reference Botha, Andevski, Bowden, Gudka, Safford, Tavares and Williams2017).

The ‘Endangered’ Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus currently suffers from the illegal use of poisons against carnivores, lead poisoning, habitat degradation, electrocution and collision with powerlines and wind farms, and decrease of food resources (Donázar et al. Reference Donázar, Palacios, Gangoso, Ceballos, González and Hiraldo2002b, Sarà and Di Vittorio Reference Sarà and Di Vittorio2003, Carrete et al. Reference Carrete, Grande, Tella, Sánchez-Zapata, Donázar, Diaz-Delgado and Romo2007, Mateo-Tomás and Olea Reference Mateo-Tomás and Olea2010, Botha et al. Reference Botha, Andevski, Bowden, Gudka, Safford, Tavares and Williams2017).

In Africa, the species ranges from the Mediterranean to sub-Saharan Africa, with some island populations in the Arabian Sea and the Eastern Atlantic, including the Cabo Verde archipelago (Ferguson-Lees and Christie Reference Ferguson-Lees and Christie2001). There are two currently recognised subspecies in the region: the nominal Neophron p. percnopterus and N. p. majorensis from the Canary Islands (Ferguson-Lees and Christie Reference Ferguson-Lees and Christie2001, Donázar et al. Reference Donázar, Negro, Palacios, Gangoso, Godoy, Ceballos, Hiraldo and Capote2002a). Island populations around Africa have suffered particularly severe declines, and the species has disappeared from Cyprus, Crete and Malta (Levy Reference Levy, Muntaner and Mayol1996), while in the Canary Islands it currently survives only on the two easternmost islands (Donázar et al. Reference Donázar, Palacios, Gangoso, Ceballos, González and Hiraldo2002b).

The Egyptian Vulture is the only vulture species occurring in the archipelago of Cabo Verde. It was an abundant species in the past (e.g. Moseley Reference Moseley1879), and during the mid-20th century the species still occupied all islands and islets (Naurois Reference Naurois1969, Reference Naurois1985, Bruyn and Koedijk Reference Bruyn and Koedijk1990), although already declining (Hazevoet Reference Hazevoet1995). Indeed, towards the end of the century, Hille and Thiollay (Reference Hille and Thiollay2000) could not find the species on Sal, Santiago and Brava, and Barone et al. (Reference Barone, Delgado and Castillo2000) presumed it had already disappeared from Sal, São Vicente and Fogo. At the turn of the 21th century, Santo Antão might have held 10–20 pairs (Palacios Reference Palacios2002), still often seen flying over the villages (L. Palma pers. obs.). Lately, the species was said to remain only in Santo Antão and Boa Vista, not exceeding 13 breeding pairs (Hille and Collar Reference Hille and Collar2011). A few years before, it was already missing from the mountains of Santiago and São Nicolau (Boughtflower Reference Boughtflower2006). Correia (Reference Correia2007) and Fernandes (Reference Fernandes2008) also could not collect any records respectively in the islands of Santiago and Fogo.

Like in the Canary Islands (Palacios Reference Palacios2000, Donázar et al. Reference Donázar, Palacios, Gangoso, Ceballos, González and Hiraldo2002b), the Egyptian Vulture’s marked decline in Cabo Verde was presumably due to various causes, among which secondary poisoning linked to retaliation against stray dogs attacks on livestock (Hazevoet Reference Hazevoet1997), the use of dangerous rodenticides and pesticides, the decrease of food resources due to periodic drought-induced losses of livestock, as well as the changes in animal husbandry (fewer available corpses and afterbirths), slaughterhouse practices (less waste) and refuse disposal (use of burning), and improved urban sanitation (cleaner streets) (Hille and Collar Reference Hille and Collar2011).

The main objective of this study was to make an assessment, as comprehensive as possible, of the species’ current situation and its conservation problems, in order to provide guidance for emergency actions and management decisions, and help in delineating a sound conservation strategy for the species in the archipelago.

In particular, due the paucity of information on the species in Cabo Verde, including field data, and in view of the limited funds and few qualified personnel for a direct field assessment, we opted to carry out extensive interviews with knowledgeable rural people that might enable us gain a broader view of the current situation and recent history. This was complemented by all other information available in publications and unpublished records of vulture sightings from various sources.

It has been shown that studies using local peoples’ perceptions can provide important insights into the social impacts and ecological outcomes of conservation, and at the same time a better understanding of the conservation implications of human behaviours and allow sounder conservation action (Martín-López et al. Reference Martín-López, Iniesta-Arandia, García-Llorente, Palomo, Casado-Arzuaga, García del Amo, Gómez-Baggethun, Oteros-Rozas, Palacios-Agundez, Willaarts, González, Santos-Martín, Onaindia, López-Santiago and Montes2012, Bennett Reference Bennett2016). Social perceptions have been used to address wildlife conservation issues, which in the case of vultures included the identification of threats (Pfeiffer et al. Reference Pfeiffer, Venter and Downs2015, Henriques et al. Reference Henriques, Granadeiro, Monteiro, Nuno, Lecoq, Cardoso, Regalla and Catry2018) and specifically the understanding of secondary poisoning prevalence (Santageli et al. Reference Santangeli, Arkumarev, Rust and Girardello2016), or the perception of how vultures are valued for the ecosystem services they provide (Morales-Reyes et al. 2018) and of their conservation importance (Cortés-Avizanda et al. Reference Cortés-Avizanda, Martín-López, Ceballos and Pereira2018). This is especially relevant in Africa where most vulture species are dwindling (Craig et al. Reference Craig, Thomson and Santangeli2018, Henriques et al. Reference Henriques, Granadeiro, Monteiro, Nuno, Lecoq, Cardoso, Regalla and Catry2018).

Conversely, these studies can also highlight the perception of vultures as a nuisance (Gbogbo and Awotwe-Pratt Reference Gbogbo and Awotwe-Pratt2008, Henriques et al. Reference Henriques, Granadeiro, Monteiro, Nuno, Lecoq, Cardoso, Regalla and Catry2018), or enable the recognition of negative attitudes towards vultures and help informing on the need of education programmes to change attitudes (Arnulphi et al. Reference Arnulphi, Lambertucci and Borghi2017). Several recent studies specifically addressed the perception of communities towards the Egyptian Vulture, generally revealing positive but heterogeneous views depending on the stakeholder profile, which may furthermore suggest conservation actions (Cortés-Avizanda et al. Reference Cortés-Avizanda, Martín-López, Ceballos and Pereira2018). On the island of Fuerteventura (Canary Islands), which shows environmental similarities with some of the Cabo Verde Islands, a similar study showed that the Egyptian Vulture is seen as a beneficial scavenging service provider, and that this view is intimately related to the persistence of traditional livestock farming (García-Alfonso et al. Reference García-Alfonso, Morales-Reyes, Gangoso, Bouten, Sánchez-Zapata, Serrano and Donázar2018).

Material and methods

Study area

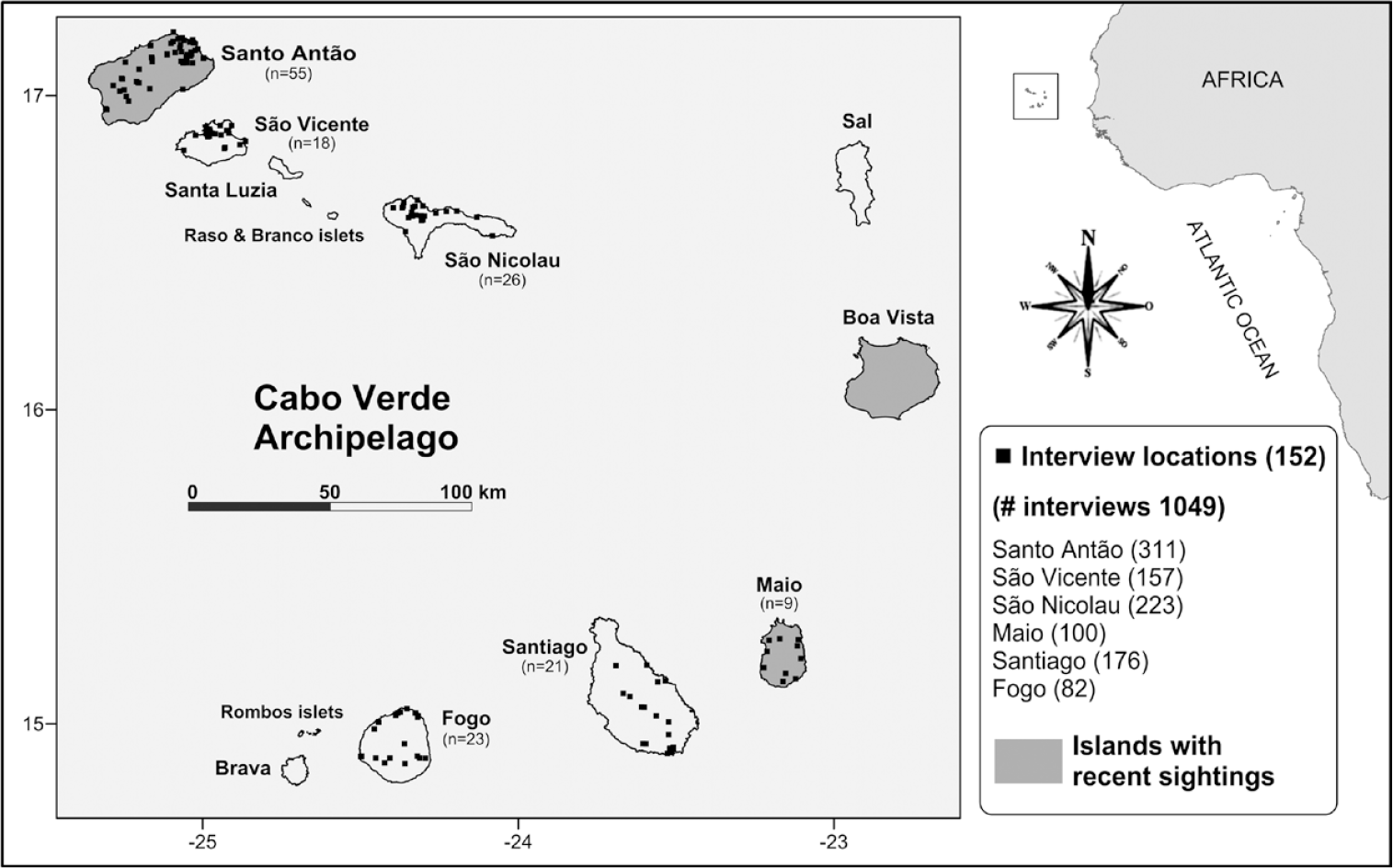

The archipelago of Cabo Verde lies in the Atlantic Ocean about 570 km off the coast of West Africa, between 14°45’–17°10’ N and 25°20’–22°40’ W (Figure 1). It comprises 10 islands and eight islets of volcanic origin with ages ranging from ∼ 3 to 15.8 Mya (Ramalho Reference Ramalho2011) and totalling an area of 4,033 km2. The younger western islands (Fogo, Brava, Santiago, Santo Antão and São Nicolau) exhibit steep relief and higher altitudes (reaching 2,828 m in Fogo) while the older eastern ones (Sal, Boa Vista and Maio) are lower (max. 406 m on Sal) and much flatter (Duarte and Romeiras Reference Duarte, Romeiras, Gillespie and Clague2009); Santa Luzia and São Vicente are of intermediate ruggedness. Cabo Verde is located within the Sahelian arid belt with a tropical arid to semi-desert climate and a wet period of one to three months (August to October). Annual precipitation barely reaches 260 mm and is unevenly distributed. Mean annual temperatures range from 23–27 °C at sea level to 18–20 °C at high altitude, but temperatures can reach 35–40 °C in the inner regions of the arid Eastern Islands. The archipelago is exposed to the north-easterly trade winds throughout most of the year, which especially affect the north-eastern slopes of the mountainous islands above 300–400 m (Duarte and Romeiras Reference Duarte, Romeiras, Gillespie and Clague2009). The archipelago of Cabo Verde is commonly divided into two island groups according to their exposure to trade winds: the Barlavento (windward) – Santo Antão, São Vicente, Santa Luzia, São Nicolau, Sal and Boa Vista; and the Sotavento (leeward) – Fogo, Santiago, Brava and Maio.

Figure 1. Cabo Verde archipelago with interviewing locations (black squares); number of interview locations per island are shown in brackets. Islands with Egyptian Vulture sightings after 2014 are shaded in grey.

Compilation of published and unpublished data

We made a broad review of Egyptian Vulture sighting records from 1998 up to 2018, retrieved from various sources: publications, unpublished reports and personal communications of ornithologists and amateur birdwatchers, plus our own observations (Table S1 in the online Supplementary Materials).

This information was used, jointly with the results of the enquiry work (see below), to estimate the current population status and recent trends, including detailed accounts for each island (Appendix S1), as well as an attempt to reconstruct the approximate chronology of the species’ decline in the archipelago (Figure 7). For the latter, as we could not use a quantitative approach due to the almost complete lack of numerical data on the species prior to our study, we established relative abundance categories based on all available sources, namely mentions of the species abundance in the literature (e.g. Naurois Reference Naurois1985, Hazevoet Reference Hazevoet1995, Hille and Thiollay Reference Hille and Thiollay2000, Barone et al. Reference Barone, Delgado and Castillo2000, Palacios Reference Palacios2002, Hille and Collar Reference Hille and Collar2011), the compilation of unpublished sighting records and our own observations (Table S1), as well as the statements of people interviewed. Because most of the available data are subjective assessments of abundance, this reconstruction attempt is inevitably approximate. Still, we believe this is a reasonable approach to the recent history of the species in the archipelago.

Additional sources of information concerning human population, livestock statistics, agrochemicals, and environmental politics were consulted, including official documents of the National Institute of Statistics, and of the current Ministry of Agriculture and the Environment.

Enquiry work: geographical and social scope and structure

We carried out 1,049 interviews during 67 days in 152 localities of the archipelago: between December 2014 and July 2015 in Santo Antão, São Nicolau, São Vicente and Santiago, and in March-April 2016 in Maio and Fogo (Figure 1, Table 1). As we sought knowledgeable individuals in order to improve the likelihood of obtaining useful information on the species in the present and recent past, most interviews were carried out with residents in rural communities who were above 40 years old, while favouring people with occupations that likely enabled more frequent contact with vultures and their habitat, or involved potential impact on the conservation of the species (Figure 2). These included farmers, forestry rangers and technicians, shepherds, garbage dump workers and slaughterhouse personnel, as well as technicians linked with agriculture, environment and sanitation issues (of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Environment, the INIDA, National Institute of Agrarian Research and Development, and Municipalities).

Table 1. Enquiry effort in 2014–2016 and percentages of responses respectively concerning vultures, livestock, pesticides and poisons, garbage disposal and slaughterhouses.

Figure 2. Occupational profiles of respondents. N is the number of respondents who declared occupation (26% of the interviewees).

We did not carry out interviews in the islands of Boa Vista, Sal and Brava. In the first case the yearly bird monitoring work done by BIOS.CV (www.bioscaboverde.com) since 2013 was judged enough for a status assessment of the species on the island, while Brava and Sal were not investigated due to time constraints and the presumption that these islands were already devoid of vultures, as confirmed on Sal (Palma Reference Palma2016).

The interviews were conducted individually and face-to-face in Cabo Verdean Creole, following prior consent of the respondent and keeping information anonymous. The interviews were semi-structured, following open-ended questions concerning: 1) sightings of vultures and their nests, and the presumed causes of decline and current threats, 2) livestock rearing systems, numbers and trends of free herding, mainly of goats, 3) pesticide use, and use of poisons like strychnine and rodenticides, 4) garbage dumps and landfills, and 5) slaughterhouses, slaughter practices and the fate of animal leftovers (Table 1). Printed photographs of Egyptian Vultures in different plumage patterns were shown to aid in identifying the species, whose vernacular name used in the interviews in each island was the one locally in use. Enquiry data were analysed in pivot tables in MS Excel from which percentage graphs were extracted and uploaded into a Geographic Information System.

In order to calculate the percentage of the rural population covered by the interviews we estimated the potential target population in each county of the sampled islands by consultation of the last (2010) official population census (INE.CV 2016a) regarding the resident rural population above 40 years old (∼22%). Then we calculated the degree of enquiry coverage as the percentage of the potential target male and female segments of the rural communities that were interviewed. Although the demographic data are from 2010, this seemed to be a reasonable approach to evaluate the study coverage rate.

Field surveys

Targeted field surveys were organised on Santo Antão in 2014–2018 and on Maio in 2015–2017 to search for vultures and their nests or signs of presence. Searches were also made in 2016 on São Nicolau and Sal (Palma Reference Palma2016). On Boa Vista, vultures were recorded circumstantially since 2012 during bird monitoring by BIOS.CV (Table S1). Brava and the small islands of Santa Luzia and nearby islets were left unsurveyed due to the lack of recent records (only one possible vagrant reported from Brava in 2017).

Results

Enquiry effort, population coverage and response output

The geographic distribution of the interviews is shown in Figure 1. The resident rural population in the whole set of counties of all islands sampled summed up to 84,924 men and 89,721 women; of these, 38,422 individuals (18,863 men and 19,739 women) were above 40 years old in 2010 (INE.CV 2016a), i.e., the potential target population, of which the 1,049 interviews represented 2.7%. With the exception of the 100 interviews carried out in Maio Is., the gender of the other 949 respondents was recorded. Among them, 837 (88.2%) were men and 112 (11.8%) women. Therefore, the enquiry work coverage in the sampled islands apart from Maio, represented 4.6% of the masculine and 0.6% of the feminine segments of the corresponding target population (i.e. without Maio, respectively 18,269 men and 19,303 women), and 2.5% of the total 37,572 individuals. Yet, the percentage of coverage varied extensively amongst these islands (men 11.7 ± 9.6 SD, 1.4–24.4%; women 1.7 ± 1.4 SD, 0.2–3.5%). Jointly considering both genders in the whole of the sampled islands, Santo Antão, São Vicente, São Nicolau and Maio had a much higher coverage (22.7 ± 7.3 SD, 10.8–29.9%) than Santiago and Fogo (1.4 and 3.0% respectively).

The number of interviews per island reflects its size, the number of inhabited places, and the extent of the current vulture range (based on the recent sighting data available, Table S1) thereby worthy of field work, as well as the logistic difficulties encountered. Thus, despite Santiago being the largest island, the number of interviews was lower there than on Santo Antão or São Nicolau, while the extent of work on the small island of Maio was comparable to that in the much larger Fogo. Particularly in Santiago, in addition to the logistical difficulties encountered, a larger sampling would be unfeasible considering the high number of rural residents above 40 yrs old (23,268). Still, as the 176 interviews were carried out in the area that we presumed to be of more suitable habitat for the species, we believe they were enough to provide a reasonable picture of the situation. Although we didn’t sample Sal, Boa Vista and Brava, the total potential target population of the three islands, i.e. rural residents above 40 yrs old (2,296 individuals), accounts for only 5.6% of the corresponding country’s total, so we assumed that this would not impact on the overall results.

Table 1 shows the distribution of the field work effort per island and the percentages of responses to each subject. The numbers of responses varied between items: while 100% of the people interviewed replied about current or past vulture occurrence, reply rates regarding other themes were in general much lower. Possible reasons for the lower response rates were the interviewees’ occupation being unrelated to the specific item in question; reluctance to answer to questions that the respondent judged sensitive; or not knowing what to respond.

Popular perceptions on historical abundances and decline

Most of the 1,049 respondents (973; 93%) claimed to have seen Egyptian Vultures but only 205 (21%) of the sightings could be assigned to a specific year in the period 1974–2015; more than half of these (118; 58%) were since 2010, probably a result of fresher recalling. Most of these more recent sightings were from Santo Antão (62; 53%) and Maio (23; 19%). Only 5% stated having seen a vulture nest, with 41 former nest sites reported, most in Santo Antão (25; 61%) and São Vicente (9; 22%) (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Geographical distribution of reports on vulture sightings (light bars) and vulture nest sites (dark bars) for the period 2010–2015 (in % of the total of sightings and nests reported). SA = Santo Antão, MA = Maio, SN = São Nicolau, SV = São Vicente, ST = Santiago, FG = Fogo.

Only 601 (57 %) respondents had some perception of decline causes: food scarcity accounted for 45% (268) of responses, the use of poisons and pesticides 31% (188), and aerial spraying against locust swarms 16% (97). Urbanisation and development were indicated as underlying causes of decline due to improved sanitation, including in animal husbandry, hence fewer carcases available for the vultures (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Percentages of responses concerning the various perceived causes of the Egyptian Vulture decline in Cabo Verde. N is the number of responses to the subject.

Poisons

Only 29 (17%) of the 174 people who answered to the use of toxics admitted using poisons to kill animals such as rodents (15; 52%), dogs (10; 34%), the Helmeted Guineafowl Numida meleagris (3; 10%), and Brown-necked Ravens Corvus ruficollis (1; 3%). On Maio, grogue (the traditional sugarcane spirit) was reportedly used as a homemade “remedy” for the poisoning of guineafowl. One respondent on Santo Antão and two on São Vicente admitted using strychnine (allegedly imported illegally) against dogs in the form of the so-called pastéis (“cakes”), i.e. fish or meat poisoned baits.

Pesticides

Aerial spraying against major swarms of the desert locust Schistocerca gregaria was often referred as a major cause of the vulture’s demise. Two big operations using malathion ULV, fenitrothion ULV and DDT were deployed in 1989 and 1990. Yet, it remained uncertain whether the reported death of vultures and other wildlife was always witnessed or only inferred from the temporal coincidence between decreases in vultures and spraying operations. Indeed, later spraying like in 2004, when chlorpyrifos ULV was used (https://tinyurl.com/y83vfhfa, in Portuguese, accessed 06 March 2018) were not quoted as affecting vultures.

Eighty one percent of respondents who answered to the use of toxins (n = 174) stated that they were routinely using phytosanitary pesticides in farms but only 1% reported impacts of these practices on vultures. Pesticides are used against e.g. the Senegalese grasshopper Oedaleus senegalensis and the green stink bug Nezara viridula. Products regularly used are propoxur, fenitrothion, carbaryl and the biological product Metarhizium anisopliae var. acridum (“Green Muscle”).

Table 2 lists the products most commonly used among those authorised by the Cabo Verde Ministry of Agriculture and the Environment (https://tinyurl.com/y7jdar8f, accessed 06 March 2018; in Portuguese).

Table 2. Active ingredients and trade names of the authorised pesticides more commonly used by farmers, according to respondents.

Tudor’s Pest Control (https://www.tudorspestcontrol.com.au/) was also referred as an authorised product but it is not in the list. Information about its active ingredient could not be found, including in the USA Environmental Protection Agency (available at www.epa.gov, accessed 10 March 2018). Among the unauthorised products referred were the “cockroach powder” allegedly bought in Chinese shops (possibly Kwik Cockroach Killer: deltamethrin 0.05% and fenvalerate 0.13%) and homemade water solutions of detergent, creolin, pepper, tobacco, bleach, sugarcane spirit, and manure.

Changes in carcass and fish processing, and refuse management

According to the respondents who reported on the type of livestock rearing (n = 282), in 57% of the cases livestock are reared in free-range, 26% in corrals and yards, and 17% indoors. Nearly half of replies about the fate of dead livestock (n = 329) stated that dead livestock are buried (54%) and 11% that they are incinerated. Allegedly though, 35% still leave carcases in the open (Figure 5), where they are eaten by dogs in 87% of responses (n=30) or by vultures, ravens and other birds (13%). Among the answers about the fate of poisoned carcases (n = 192), most (94%) claimed they are buried and 4% that they are incinerated or left in the open (2%).

Figure 5. Fate of dead livestock carcases according to shepherds. N is the number of responses to the subject.

Official municipal slaughterhouses exist on all inhabited islands, while in Santiago the existence of informal slaughterhouses was also reported. Livestock taken to municipal slaughterhouses consists predominantly of cattle, less often pigs and goats, but traditional homemade slaughter is still a common practice in many localities, being the most popular in the case of goats.

In coastal localities fish are no longer eviscerated, salted and dried on the beach as described by Naurois (Reference Naurois1985), and are now directly sent for sale. Allegedly, 14 years ago when fish salting and drying was still done on beaches, many vultures gathered to feed.

Old informal garbage dumps have been gradually discontinued since the mid-1990s and replaced by modern official ones. Still, several old ones still operate in the Barlavento (Table 3), while trashing in stream beds is still reported, e.g. on Maio.

Table 3. Number of garbage dumps on the islands surveyed.

Current population status and recent trends

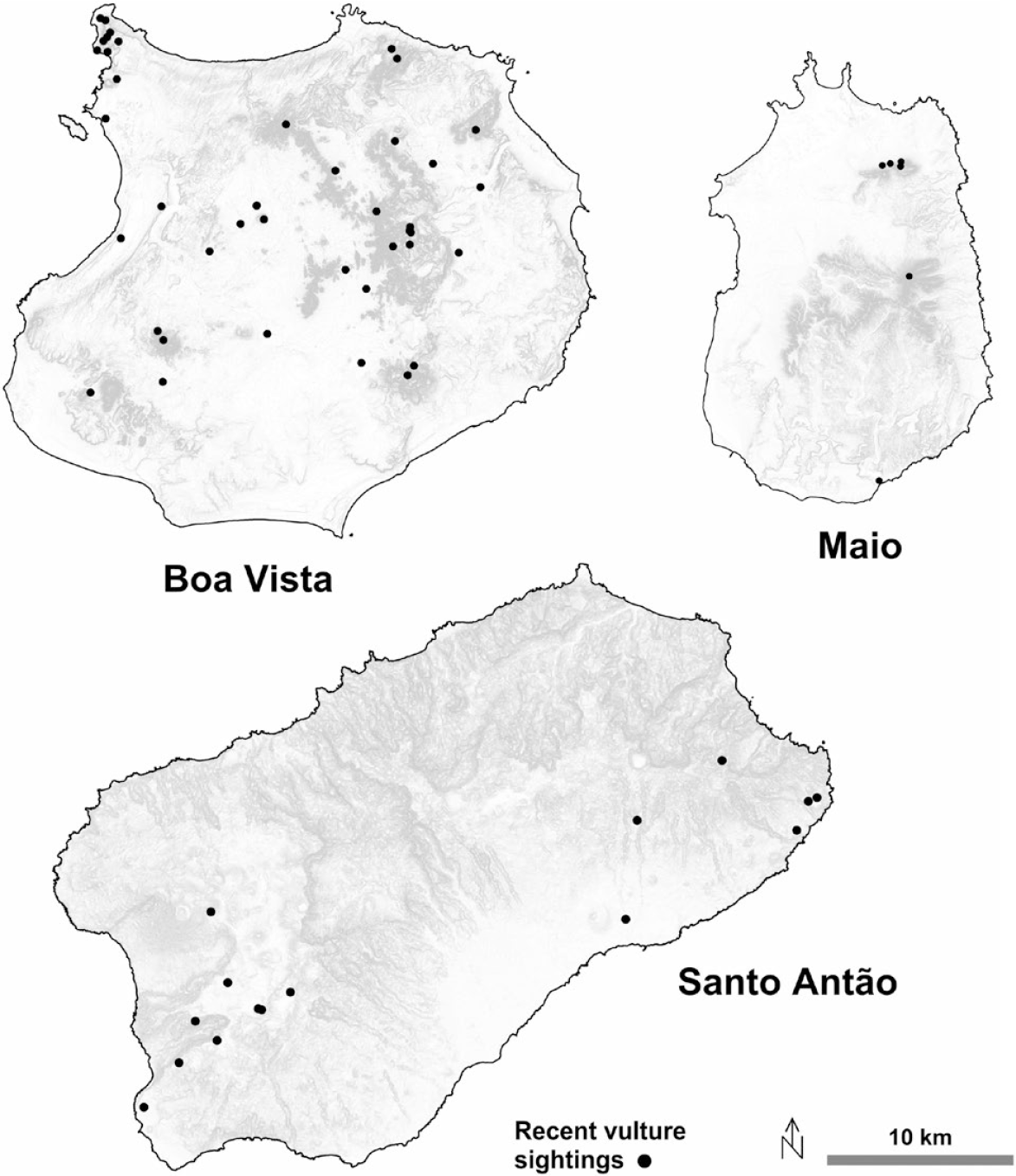

On Santo Antão, there were nine sightings of vultures during the 2014–2018 target searches, plus eight circumstantial sightings. With two exceptions, in all 17 circumstances birds observed were adults and all were seen in or close to the desert areas of the south and west (Figure 6). In 2016, many old whitewashes were seen by Palma (Reference Palma2016) throughout Santo Antão, a clear indication of the species’ former abundance, while rare fresh droppings were found only in the south and south-west, whereas on São Nicolau no vulture was seen and only one possible old roost was found. No vulture, sign or oral record of the species could be collected on Sal. On Boa Vista, monitoring by BIOS.CV yielded 89 sightings in 2013–2018 (Table S1). On Maio, field searches produced five sightings in 2015, in three of which two adults were seen together. One adult was observed near a refurbished nest. Four additional adults were circumstantially sighted in 2017 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Distribution of Egyptian Vulture sightings in 2014–2018 (black dots) in Boa Vista, Maio and Santo Antão. Dots may refer to more than one sighting. Digital Terrain Model produced by the Cabo Verde National Institute of Land Management (INGT). Available at http://ingt.maps.arcgis.com [accessed on open-share, 20 April 2018].

The reconstruction attempt of the Egyptian Vulture’s decline during the last c.50 years on the larger islands, based on bibliographic sources, unpublished sighting records (Table S1), interviews (present study) and authors’ observations, is shown in Figure 7. Population decrease was more intense during the 1980s–1990s, when even abundant subpopulations quickly crashed to residual numbers and vanished. On Sal and Brava the species seems to have been always rare, but persisted at least in the late 1990s on Sal. In turn, on Santa Luzia and the islets of Branco, Raso and Rombos the species seemed to have been rare in the past but its history could not be tracked. Detailed accounts per island are presented in Appendix S1.

Figure 7. Reconstruction attempt of the Egyptian Vulture sequence of decline in Cabo Verde since the 1960s. Abundance categories: 4 = abundant, 3 = common, 2 = scarce, 1= rare, 0 = extinct.

Based on the most recent information (Monteiro et al. Reference Monteiro, Fortes, Freitas and Palma2015, Reference Monteiro, Fortes, Freitas and Palma2017, Palma Reference Palma2016; BIOS.CV’s bird monitoring unpubl. reports) and the present study field data, a preliminary conservative estimate for the Egyptian vulture in Cabo Verde is of 7–11 pairs: 4–6 pairs on Santo Antão, 2–3 pairs on Boa Vista and 1–2 pairs on Maio. However, this estimate may be slightly optimistic as so far we could not confirm on Santo Antão that all presumed “pairs” are de facto pairs. It seems almost certain that the species no longer breeds on any of the remaining islands. Furthermore, the small number of non-adults seen is an indication that breeding may occur only irregularly.

Discussion

The demographic history of the Egyptian Vulture in Cabo Verde mirrors to some extent that of the Canary Islands where the establishment of the species matches the human colonisation of the archipelago about 2,500 years ago, profiting from the abundance of food resources brought in by humans (Agudo et al. Reference Agudo, Rico, Vilà, Hiraldo and Donázar2010). In Cabo Verde, it is not known how long the species has inhabited the archipelago, but probably it also benefited from the human colonisation in the 15th century (Albuquerque 2001). Goats and unmanaged waste allowed vulture populations to increase to unprecedented levels, as described by Moseley (Reference Moseley1879), Bannerman (Reference Bannerman1912) and other early authors (cited by Naurois Reference Naurois1985). This abundance could still be witnessed in Cabo Verde during the 1960s around growing towns with poor sanitation (Naurois Reference Naurois1985). Worldwide, this ancient relationship with humans has been disrupted by contemporary activities (Moleón et al. Reference Moleón, Sánchez-Zapata, Margalida, Carrete, Owen-Smith and Donázar2014) as happened in the Canary Islands (Palacios Reference Palacios2000, Donázar et al. Reference Donázar, Palacios, Gangoso, Ceballos, González and Hiraldo2002b, García-Alfonso et al. Reference García-Alfonso, Morales-Reyes, Gangoso, Bouten, Sánchez-Zapata, Serrano and Donázar2018) and later in Cabo Verde (Hazevoet Reference Hazevoet1995, Hille and Thiollay Reference Hille and Thiollay2000, present study).

Population decline and causal factors

This is the first approach to a comprehensive assessment of the Egyptian Vulture conservation status in Cabo Verde. All available sources indicated a precipitous decline in the last three decades, apparently more abrupt during the last two, and affecting all islands. Egyptian Vultures began to decrease shortly after the independence of Cabo Verde in 1975, in parallel with the country’s economic growth and development, which translated into urban expansion, modernisation and better sanitation (UN Cape Verde 2010, WHO and UNICEF 2017, African Union 2018). Official statistics clearly show a marked urbanisation trend with the percentage of the urban population growing from 11% to 67% between 1970 and 2016; the population using improved sanitary facilities increased from 12.2% in 1980 to 80.3% in 2016 (INE.CV 2016b).

At the same time, the marked drop in the number of rural inhabitants between 1970 and 2016 (-27%: 241,226 > 175,167), whereas the country’s population doubled (+49%: 270,999 > 530,931), highlights the extent of the rural exodus, also reported to us during the interviews as being related to increased aridity. Livestock production (INE.CV 2016b) shows a fluctuating trend in goat numbers (presumably mostly free-ranging) between 1998 and 2015, with a steady increase from 95,338 (1998) to 148,094 head (2004), and then a -27% drop in 11 yrs (107,630 head in 2015). Free-ranging small livestock (sheep and goats) is a factor better explaining the persistence vs. abandonment of Egyptian Vulture territories in Europe (Sarà and Di Vittorio Reference Sarà and Di Vittorio2003, Mateo-Tomás and Olea Reference Mateo-Tomás and Olea2010). Therefore, the decrease in free-ranging goat herding in Cabo Verde, together with reduced food supply from other sources, must have had a marked impact on food availability. The highly predictable food source represented by open-air landfill sites is an important factor shaping the distribution of Egyptian Vulture breeding territories, favouring productivity and the gathering of immatures at dump sites (Tauler-Ametller et al. Reference Tauler-Ametller, Hernández-Matías, Pretus and Real2017), even if feeding at dumps is not free of negative effects on body condition and health of the vultures (Tauler-Ametller et al. Reference Tauler-Ametller, Pretus, Hernández-Matías, Ortiz-Santaliestra, Mateo and Real2019).

This decrease in food resources co-occurred with the long-lasting and widespread use of dangerous substances to cause the observed vulture decline. In particular, the retaliatory poisoning of stray dogs may have had a central role in the near eradication of vultures. Strychnine was frequently used in the past, and despite being illegal, it seems that is still available. Stray dogs are still abundant throughout the archipelago and the cause of substantial mortality of free-ranging livestock, with a major impact on the small-scale rural economy. Therefore, poisoning will presumably not halt until dog predation upon livestock is effectively and efficiently tackled. This problem resembles the widespread conflict between wild predators and herders with the well-known serious consequences of illegal wildlife poisoning (Mateo-Tomás et al. Reference Mateo-Tomás, Olea, Sánchez-Barbudo and Mateo2012, Ogada Reference Ogada2014, Santangeli et al. Reference Santangeli, Arkumarev, Rust and Girardello2016, Reference Santangeli, Arkumarev, Komen, Bridgeford and Kolberg2017, Safford et al. Reference Safford, Andevski, Botha, Bowden, Crockford, Garbett, Margalida, Ramírez, Shobrak, Tavares and Williams2019). Egyptian Vultures have been one of the victims in Europe (Hernández and Margalida Reference Hernández and Margalida2009) where ongoing illegal poisoning is largely due to a lack of enforcement of existing legislation (Margalida and Mateo Reference Margalida and Mateo2019).

Besides mortality, large-scale spraying against locusts may have also caused morbidity and impaired fecundity due to the high toxicity to birds of fenitrothion and chlorpyrifos (used in the 2004 spraying) and the moderate toxicity of malathion (PPDB 2018). Chlorpyrifos and other organophosphates have been shown to represent a potential risk to avian scavengers when used as topical anti-parasitics in livestock (Mateo et al. Reference Mateo, Sánchez-Barbudo, Camarero and Martínez2015). DDT in turn, which had been openly sold and extensively used in agriculture since the 1960s until its ban in the late 1980s, may have also considerably contributed to the vulture decline for its chronic deleterious effects in fecundity (Hickey and Anderson Reference Hickey and Anderson1968).

Only vultures living in desert rangelands were presumably spared the effect of pesticides, but these areas offer scantier food resources. Indeed, on Boa Vista, despite the current livestock abundance, vultures remain few, supporting the idea that the former vulture abundance in the “green” areas of the mountainous islands was due to the higher food availability once provided by unmanaged refuse in urban and farmland areas.

Ongoing contamination

Hazardous substances have in general been banned, but some of those authorised and most in use in Cabo Verde are not harmless, such as fenthion, fenitrothion, imidacloprid and propoxur, which are highly toxic to birds (PPDB 2018). Despite the moderate toxicity of malathion to raptors, it may nonetheless cause some mortality and sub-lethal effects (Ortego et al. Reference Ortego, Aparicio, Muñoz and Bonal2007). In particular, malathion and chlorpyrifos have been shown to cause Egyptian Vulture mortality (Hernández and Margalida Reference Hernández and Margalida2009).

Some unlisted and illegal products seem still easily bought and used. Although DDT is now banned, several responses suggested that it may still be in use and somehow available. Moreover, due to its persistence and that of its metabolites (Johnstone et al. Reference Johnstone, Court, Fesser, Bradley, Oliphant and MacNeil1996, Sørensen et al. Reference Sørensen, Vorkamp, Thomsen, Falk and Møller2004) it may probably still be circulating in the environment. Furthermore, to compensate for the difficulty in acquiring strychnine after the ban, other products (e.g. unidentified rodenticides and insecticides) purchased at Chinese shops have seemingly become increasingly popular against agricultural pests and dogs. However, neither the administration nor the general public knows what their chemical composition is.

Electrocution and collision risks

Raptor electrocution is a worldwide conservation concern, and one of the drivers of risk is pole configuration (Lehman et al. Reference Lehman, Kennedy and Savidge2007, Guil et al. Reference Guil, Fernández-Olalla, Moreno-Opo, Mosqueda, Gómez, Aranda, Arredondo, Guzmán, Oria, González and Margalida2011). Most of the medium-voltage powerline poles of Cabo Verde are three phase T-structures with flat or vaulted horizontal cross-arm configurations and all-exposed pin-type insulators and jumpers above the cross-arm. This most dangerous design (Kruger and van Rooyen Reference Kruger, van Rooyen, Chancellor and Meyburg2000, Mañosa Reference Mañosa2001, Janss and Ferrer Reference Janss and Ferrer2001, Adamec Reference Adamec, Chancellor and Meyburg2004, Tintó et al. Reference Tintó, Real and Mañosa2010), has been responsible for large numbers of electrocuted Egyptian Vultures in East Africa (Angelov et al. Reference Angelov, Hashim and Oppel2013). In Cabo Verde, two adult Egyptian Vultures were found electrocuted in 2018, respectively on Santo Antão and Boa Vista. During a first survey of the c.25-km long powerline network of Boa Vista by BIOS.CV in December 2018, the remains of 20 Ravens, one Osprey Pandion haliaetus and one guineafowl were found electrocuted under the pylons.

The adverse impacts of wind farms through the occupation of biologically sensitive areas and especially from collision with turbines are a well-known and universal threat to raptors, and among these, vultures in particular (Martínez-Abraín et al. Reference Martínez-Abraín, Tavecchia, Regan, Jiménez, Surroca and Oro2012, Carrete et al. Reference Carrete, Sánchez-Zapata, Benítez, Lobón, Montoya and Donázar2012, Sánchez-Zapata et al. Reference Sánchez-Zapata, Clavero, Carrete, DeVault, Hermoso, Losada, Polo, Sánchez-Navarro, Pérez-García, Botella, Ibáñez and Donázar2016). As seen in Spain, where more than one-third of all Egyptian Vulture breeding territories lie within the risk buffers of wind farms, the risk to the species can be high (Carrete et al. Reference Carrete, Sánchez-Zapata, Benítez, Lobón and Donázar2009).

In Cabo Verde, there are four wind farms on four different islands, run by the national wind power company Cabeólica S.A (www.cabeolica.com). Currently, only the small Boa Vista wind farm (3 turbines in 18 ha) is potentially problematic to the Egyptian Vulture as the species is now absent from the other three islands. So far, the yearly monitoring of this wind farm since its construction in 2012 (BIOS.CV unpublished reports to Cabeólica) has not revealed mortality or displacement effect on local birds or transient vultures, which continue to use the vicinity of the farm.

Present situation, conservation needs and perspectives

The critical situation of the Egyptian Vulture in Cabo Verde calls for urgent measures to save the relict nuclei, on which the species survival in the country depends, including: 1. The complete halt to illegal poison use, alongside an effective and sustainable tackling of stray dog predation on livestock; 2) revision of the legal status of dangerous pesticides still in use; and 3) the retrofitting of dangerous sections of powerlines, at least in what is left of the vulture distribution.

A supplementary feeding programme may also be important to maintain the remaining breeding pairs and improve their status. However, few leftovers remain from slaughterhouses as carcases are almost fully processed, or in households where the remains of small livestock carcases are used to feed pigs. Poultry farms, besides being few in the country, may not be the best alternative in case veterinary drugs are used, because of the related health risks to vultures (Blanco et al. Reference Blanco, Junza and Barrón2017). Still, other sources of food can be investigated, such as the leftovers from fish markets, which may represent an easy source of supplementary food. Whatever the most feasible solutions, the feeding scheme should follow the recommended optimisation guidelines for supplementary feeding of Egyptian Vultures (e.g. Moreno-Opo et al. Reference Moreno-Opo, Trujillano, Arredondo, González and Margalida2015).

In the long run, assisting traditional goat and cheese production may be essential for maintaining and enhancing vulture food resources. The importance of traditional small livestock pastoralism for the conservation of the Egyptian vulture has been demonstrated elsewhere (Sarà and Di Vittorio Reference Sarà and Di Vittorio2003, Mateo-Tomás and Olea Reference Mateo-Tomás and Olea2010, García-Alfonso et al. Reference García-Alfonso, Morales-Reyes, Gangoso, Bouten, Sánchez-Zapata, Serrano and Donázar2018) and is probably also key to improving the species’ food supply in Cabo Verde on a sustainable basis. Intimately linking vulture conservation with improvements in goat production would be a step forward to reinventing mutualism sensu Gangoso et al. (Reference Gangoso, Agudo, Anadón, de la Riva, Suleyman, Porter and Donázar2013).

However dramatic the situation may be, the recent recovery of the formerly highly endangered population of the Canary Islands shows that with the right level of conservation investment and effort, namely the alleviation of poisoning and electrocution casualties (https://canarianegyptianvulture.com, accessed 12 August 2018) it is possible to revert the fate of an island population of the ‘Endangered’ Egyptian Vulture.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959270919000376

Acknowledgements

We are indebted to: Wind power company Cabeólica S.A., Santo Antão Protected Areas and Fogo Natural Park, Delegations of the Ministry of Agriculture and the Environment of Santo Antão, São Nicolau, São Vicente and Fogo, the Town Halls of São Vicente, Paúl and Ponta do Sol in Santo Antão, the Praia Municipal Sanitation Services, and INIDA, for providing logistical support and/or information. We also thank: Nathalie Almeida and Rosiane Fortes for helping in interviews; Rogério Cangarato, the shepherds César Fortes, “Primo”, Romão and Manuel (“Manel”) for their help in field monitoring; and Cornelis Hazevoet for the compilation of unpublished observations. We also thank Marina Temudo for clarifying enquiry methods and an anonymous referee for the thorough review that allowed much improvement of the manuscript. Finally, we are grateful to all people who agreed to respond to the enquiry. This article is an output from the Portuguese - Cabo Verde TwinLab, established between CIBIO/InBIO and the University of Cabo Verde. L. Palma was supported by Portuguese national funds through FCT – Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia, I.P. This work was supported by AFdPZ - Association Française des Parcs Zoologiques, VCF - Vulture Conservation Foundation, Fondation Ensemble, Cabeólica S.A. and DNA - Cabo Verde National Directory for the Environment. This study was conducted with the acknowledgement and support of the Cabo Verde national and regional authorities of the environment and agriculture. Enquiries were carried out under the supervision of the University of Cabo Verde and with prior consent from the people interviewed.