1. Introduction

Contextual language learning refers to language learning as part of (communicative) activities that do not focus on language learning itself, (Elgort, Brysbaert, Stevens & Van Assche, Reference Elgort, Brysbaert, Stevens and Van Assche2018). Recent studies have shown that learners can acquire considerable L2 language competence through contextual learning, sometimes even before the start of formal instruction (De Wilde, Brysbaert & Eyckmans, Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a; Lefever, Reference Lefever2010; Puimège & Peters, Reference Puimège and Peters2019). These studies all involved the English language and illustrate that the availability of English has changed the status of English in some non-English-speaking countries, an observation already made by de Bot in 2014. This hybrid status of English has characteristics of both a foreign language – as it is not an official language – and a second language – as it is very present in everyday life (e.g., through media and advertising).

The ready availability of English leads to a situation in which children enter formal English education with prior L2 knowledge. In the present study we investigated how the learners’ prior knowledge interacts with formal instruction when the children attend English classes in school. We also looked at the influence of selected individual difference variables on differential L2 English language learning.

2. Classroom instruction

Formal classroom teaching is characterised by the presence of a teacher explaining the content in a systematic way. Learning in formal contexts (also) leads to explicit knowledge about a topic (Malcolm, Hodkinson & Colley, Reference Malcolm, Hodkinson and Colley2003). With regards to formal language teaching, research has found that explicit instruction and activities focusing on form are very efficient and lead to larger language gains than more implicit activities (Norris & Ortega, Reference Norris and Ortega2000; DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser, Doughty and Long2003), even though they are not sufficient on their own for proficient language use (Bybee & Hopper, Reference Bybee and Hopper2001; Ellis, Reference Ellis2002). In light of the large differences between children's prior knowledge of English before classroom instruction (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a; Puimège & Peters, Reference Puimège and Peters2019), the question arises how the learners’ L2 English proficiency develops after the introduction of formal instruction. Does explicit classroom instruction close the gap, rendering the group more homogenous in level of English proficiency by the end of the year? Alternatively, does it engender a Matthew effect (the rich get richer and the poor get poorer), thereby accentuating the gap? Or does formal education leave the initial differences unaltered, simply adding the same degree of (explicit) knowledge for everyone?

Previous longitudinal studies involving young learners mainly looked at the effects of an early start of English lessons. A longitudinal study, conducted in the Netherlands by Unsworth, Persson, Prins and De Bot (Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and De Bot2015), looked at how input affected very young learners of English as L2 (average age at the baseline measurement was 4 years) over time. Data were collected at three points in time: at the start of the English lessons and after one and two years of English lessons. The results showed that weekly classroom exposure of more than 60 minutes per week led to significantly higher scores. There was a significant improvement after one and two years of instruction both for receptive vocabulary and receptive grammar knowledge.

A study by Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter (Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017) looked at the effect of an early start on the proficiency of older learners (age 12–13). The study showed that learners starting English classes at a later age (8–9 years) outperformed early starters (starting age 6–7 years) on tests of receptive knowledge (reading and listening skills) when they were 12–13 years old, even though the reverse had been true two years earlier. One of the explanations given by the authors was that the teaching time and methods used in early English education did not have a lasting impact, because they were not intensive enough and had little focus on explicit teaching of form. Older learners seemed to make faster progress, arguably because they benefited from more form-focused, rule-based teaching.

The context of our study is different from previous longitudinal studies with young learners as L2 English learning in Flanders starts much later than in the studies discussed above. As Belgium has three official languages (Dutch, French and German) and a bilingual Dutch-French capital region Brussels, it has been decided by decree that French is the first foreign language to be taught at school. English classes typically start only in the first or second year of secondary education (i.e., at the age of 12–13 years). Because exposure to English is considerable in Belgium, many children have prior knowledge of English before the start of formal instruction. The focus of this longitudinal study is on how the children's language learning is affected by the introduction of classroom L2 English instruction, in order to shed more light on the effectiveness/dynamics of formal and informal learning in young learners. The influence of classroom instruction cannot be studied in isolation. Many other factors are at play. We will look into some of these variables in the next section.

3. Individual differences involved in language learning

Many studies investigating individual differences in L2 learning concern language learning in adults. A few recent studies (Paradis, Reference Paradis2011; Sun, Steinkrauss, Tendeiro & De Bot, Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Tendeiro and De Bot2016; Sun, Steinkrauss, Wieling & De Bot, Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Wieling and de Bot2018a; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and De Bot2015) looked at the interplay of individual differences in (very) young children learning an L2. The studies considered both internal, cognitive variables such as working memory and analytic reasoning ability and external variables such as amount of exposure, type of exposure and teacher proficiency. The study by Paradis (Reference Paradis2011) looked into language acquisition in young heritage learners (ages 4–7) and found that internal, cognitive factors explained more variance than external factors. Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Tendeiro and De Bot2016) investigated language learning in 71 young Chinese learners of English (ages 2–6) and found the opposite: namely, that external factors explained more variance in children's language proficiency than internal factors. A third study by Sun and colleagues (Sun, Yin, Amsah and O'Brien, Reference Sun, Yin, Amsah and O'Brien2018b) looked at internal and external differences in 805 Singapore four- to five-year-old children learning English and an ethnic language (Mandarin / Malay / Tamil). The researchers found that more variance was explained by internal factors for English learning and by external factors for learning an ethnic language. The authors believe this difference was due to the learning environment. Internal factors seemed to explain more variance in the language for which learners have a lot of input (in this context English), which is in line with Paradis (Reference Paradis2011). External factors explained more variance in an input-poor environment, which is in line with Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Tendeiro and De Bot2016).

The context of our study is different from the previous studies as English is not an official language in Flanders but children are exposed to a lot of English through different media. Furthermore, formal classroom instruction in the L2 starts much later in Flanders than in all studies run so far. When it comes to the learners’ L1, Dutch is more closely related to English than others – e.g., Chinese – and previous studies have shown the importance of cognates in language learning (Goriot, van Hout, Broersma, Lobo, McQueen & Unsworth, Reference Goriot, van Hout, Broersma, Lobo, McQueen and Unsworth2018; De Wilde, Brysbaert & Eyckmans, Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020b). It is therefore interesting to investigate what the contribution of internal and external factors is in a context where the L2 is neither the majority language nor a completely new, foreign language and where formal instruction is often preceded by contextual language learning. Individual differences related to exposure (in and out of the classroom), cognitive differences and prior knowledge are discussed below.

3.1. Out-of-school exposure

Various studies have shown that out-of-school exposure has a positive influence on language learning. Studies by Lindgren and Muñoz (Reference Lindgren and Muñoz2013), Sylvén and Sundqvist (Reference Sylvén and Sundqvist2012) and Peters (Reference Peters2018) showed how watching television, gaming, etc. positively influence L2 English learning. Moreover, studies by De Wilde et al. (Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a), Puimège and Peters (Reference Puimège and Peters2019) and Lefever (Reference Lefever2010) indicated that young learners learn substantive amounts of English solely through out-of-school exposure, before the start of formal instruction. De Wilde et al. (Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a) found that in a context where there were ample opportunities to access English input, participants who were involved in gaming, using social media or speaking English had the largest gains. The results were explained by the element of production in these types of exposure. This was not the case for other types of input that were investigated (watching television and listening to music). Puimège and Peters (Reference Puimège and Peters2019) also found a positive influence of gaming, especially for the older learners in the study (age 12). They further found a positive influence of watching television on a meaning recognition task.

3.2. Length of instruction

The amount of teaching time dedicated to foreign language learning also impacts L2 proficiency. Researchers have found that length of instruction (number of years and hours of instruction) affects language learning. More teaching time generally leads to better performance.

Muñoz (Reference Muñoz2011, Reference Muñoz2014) was one of the first to highlight the influence of length of instruction. The studies showed that length of instruction, rather than age at which instruction started, influenced learners’ proficiency. Apart from length of instruction, other types of (out-of-school) exposure were also significant predictors of L2 English proficiency, pointing to the importance of all kinds of input, inside and outside the classroom. Later studies by Peters, Noreillie, Heylen, Bulté and Desmet (Reference Peters, Noreillie, Heylen, Bulté and Desmet2019) looking at secondary school pupils learning French and English, and Unsworth et al. (Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and De Bot2015) investigating English learning in young children, have also shown the positive influence of length of instruction on L2 learning.

3.3. Cognitive variables

The role of cognitive variables has been widely investigated in language learning. Below, we discuss the studies looking into the influence of these variables specifically in young adolescent L2 learners.

A longitudinal study conducted by Csapó and Nikolov (Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009) investigated how the inductive reasoning skills of Hungarian children influenced their English or German L2 listening, reading and writing skills. Over 40,000 children were included. The researchers found moderate to strong relationships between inductive reasoning and English proficiency for learners age 12 but the correlations became weaker over time. The researchers also found that correlations between inductive reasoning and L2 reading (and sometimes writing) were higher than for L2 listening. In the longitudinal part of the study, regression analyses showed different patterns in the different age groups and languages. Inductive reasoning explained more variance in the younger age groups and more variance for English than for German (highest R 2 = .08 was found in younger learners of English). A decade later, the same researchers conducted a similar study (Nikolov & Csapó, Reference Nikolov and Csapó2018) in which they investigated the relationship between inductive reasoning skills and L2 reading in English and German in Hungarian 14-year-olds. This study showed a larger impact of inductive reasoning: the variable explained 26.9% of the variance in L2 English reading and 19.3% of the variance in German reading achievements. The researchers recommend further research, which also takes into account other cognitive variables to explain these mixed findings.

Ranta (Reference Ranta and Robinson2002) investigated the role of (language) analytic abilities on L2 language learning in 11- to 13-year-old francophone children studying English in an intensive program focusing on communicative skills and fluency. Analytic abilities were tested with an L1 metalinguistic task (error detection and correction). A cluster analysis (with four clusters) revealed that learners with a high score on the metalinguistic task also had a high score on L2 measures. The same was true for the cluster with the lowest score. Overall, the learners’ language ability, which was measured with an L1-metalinguistic task, only weakly predicted learners’ L2 learning success although analytic abilities seemed to impact L2 learning in the highest and lowest performing groups.

Another cognitive variable that has received some attention in studies with young adolescent L2 learners is working memory capacity. Kormos and Sáfár (Reference Kormos and Sáfár2008) conducted a study with Hungarian 15- to 16-year-old learners of English who were enrolled in an intensive language training program. The researchers were interested in the relationship between the learners’ language skills, their phonological short-term memory and complex verbal working memory capacity. The results on a backwards digit span task (which measured complex verbal working memory capacity) accounted for 30% of the variance in the overall language test score. Tests of phonological short-term memory were significantly correlated with learners’ fluency and vocabulary size in pre-intermediate learners, but no significant effects were found for beginners. A possible interpretation is that phonological short-term memory plays a larger role in contextual learning (typical for the later learning stages in the context of Kormos & Sáfár, Reference Kormos and Sáfár2008) than in explicit learning (typical for the early learning stages in this study).

A study by Michel, Kormos, Brunfaut and Ratajczak (Reference Michel, Kormos, Brunfaut and Ratajczak2019) looked into the role of working memory in young L2 learners’ writing skills (see also Juffs & Harrington, Reference Juffs and Harrington2011, for a more general review). The learners (age 11–14), who were enrolled in a bilingual program in Hungary, took a writing test and a series of working memory tests. The results showed that the storage and processing function of working memory had only a limited effect on learners’ writing scores. According to the authors, the instruction the participants received might have reduced the variation in writing skills that could be affected by working memory.

Other studies (Cheung, Reference Cheung1996; Gathercole & Masoura, Reference Gathercole and Masoura2005; Service & Kohonen, Reference Service and Kohonen1995) have investigated the role of phonological short-term memory in L2 vocabulary learning in young learners (12-year-old learners in Hong Kong, Greek children age 8–13 and Finnish learners age 9–12 respectively). The studies all found that phonological short-term memory plays a role in the early stages of vocabulary learning in a foreign language learning context (see also Linck, Osthus, Koeth & Bunting, Reference Linck, Osthus, Koeth and Bunting2014).

Overall, the results of studies investigating cognitive variables in young adolescent L2 learners show mixed effects depending on the language learning contexts (e.g., bilingual education) and the learners’ L2 proficiency. To the best of our knowledge, the role of these individual differences has not yet been investigated in a foreign language learning context in which learners are exposed to and may have picked up elements of the L2 through contextual language learning previous to formal classroom instruction.

3.4. Prior L1 and L2 knowledge

Finally, we give a brief overview of studies examining the effect of prior L1 and L2 knowledge on L2 proficiency. About 40 years ago, Cummins (Reference Cummins1979, Reference Cummins1984) already formulated the interdependence hypothesis, which stated that L2 development was dependent on L1 proficiency. Many studies have established that L2 learning is strongly influenced by proficiency in L1. Sparks (Reference Sparks2012) reported on a number of studies conducted over the course of 25 years with L2 learners in secondary and post-secondary education in the United States, which consistently showed that there is a connection between L1 skills and L2 proficiency. Snow and Kim (Reference Snow, Kim, Wagner, Muse and Tannenbaum2007) argued that one may expect a positive correlation between learners’ L1 and L2 vocabulary size as the aptitude enabling children to pick up words in L1 will also help them to learn words in L2. Furthermore, children with larger L1 vocabularies already know more concepts for which they only have to learn the form in L2. Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Yin, Amsah and O'Brien2018b) and Puimège and Peters (Reference Puimège and Peters2019) have indeed shown that L1 vocabulary knowledge positively impacts L2 word learning. Furthermore, studies have shown that similarities between the L1 and the L2 facilitate L2 learning both when it comes to the acquisition of morphosyntax (Paradis, Reference Paradis2011; Blom, Paradis & Duncan, Reference Blom, Paradis and Duncan2012) and when it comes to vocabulary learning (Goriot et al., Reference Goriot, van Hout, Broersma, Lobo, McQueen and Unsworth2018; De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020b).

Another factor that has been shown to affect the rate of L2 learning is prior knowledge of the target language. Several longitudinal studies with young L2 learners found it was often one of the strongest predictors of learners’ L2 knowledge and skills. Jaekel et al. (Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017) investigated children's receptive skills and a number of individual differences in year 5 and year 7. They could explain 35% more variance in year 7 than in year 5, because they could add proficiency in year 5 as an extra predictor. Similar results were found by Unsworth et al. (Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and De Bot2015) and Csapó and Nikolov (Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009). All these studies looked into L2 knowledge that was the result of formal instruction. The children in our study picked up L2 English through contextual language learning. Below, we will investigate whether L2 prior knowledge and skills gained through this type of learning alone are as predictive for L2 development.

4. Aims and research questions

In the present study we investigate how formal instruction and other, external and internal, individual differences influence young learners’ English language proficiency. The external variables investigated in this study are length of instruction and out-of-school exposure; the internal variables are working memory, analytic reasoning ability, Dutch vocabulary knowledge and prior knowledge of English.

The research questions are:

(1) How much does learners’ L2 proficiency improve after the onset of instruction?

(2) Do individual differences in L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills at the onset of instruction decrease in the course of formal instruction?

(3) What is the impact of individual differences (length of instruction, out-of-school exposure, working memory, analytic reasoning ability, Dutch vocabulary knowledge, and prior knowledge of English) on the children's L2 English proficiency at time 2?

With regard to the first research question, we hypothesize that children's vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills will improve over time and after the onset of instruction. Indeed, that is the purpose of L2 teaching; and previous longitudinal research in L2 instruction (Csapó & Nikolov, Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009; Jaekel et al., Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and De Bot2015) has confirmed that children's L2 proficiency increases over time. However, there is much less information about how much children learn in the first year of L2 teaching.

As for the second research question, there are considerable differences in L2 knowledge at the start of formal education, due to differences in contextual learning (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a). Some children have picked up more English words and understand and produce more English than other children. How does this interact with formal teaching? On the one hand, one could assume that formal teaching will decrease the entry differences of the pupils, because the lesson content at the start of formal instruction might overlap with what is already known, and children with prior knowledge may not learn much new in the first months. On the other hand, the introduction of formal instruction could engender a Matthew effect and help the children with prior knowledge more than those without. Formal classroom instruction offers instances of explicit learning and a focus on form, which are beneficial for L2 language learning (Norris & Ortega, Reference Norris and Ortega2000; DeKeyser, Reference DeKeyser, Doughty and Long2003). This may be particularly true for children who already have a firm basis of implicit L2 knowledge. Finally, it is possible that the effects of contextual learning and formal learning are additive: all children profit to the same extent from formal teaching and the entry differences remain stable. This would be the case if the implicit knowledge learned from everyday interactions and the explicit knowledge learned in class were largely complementary in (early) L2 acquisition.

The third research question addresses the role of individual differences in L2 acquisition. We are interested in the degree to which internal and external differences explain variability in the children's L2 proficiency at time 2. Previous studies with young children have shown that more variance is explained by internal differences in an English as Second Language (ESL) context and by external variables in an English as Foreign Language (EFL) context (Paradis, Reference Paradis2011; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Tendeiro and De Bot2016; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Wieling and de Bot2018a). At the same time it has been observed that the position of English in some European countries seems to be hybrid, showing characteristics of both a second and a foreign language (de Bot, Reference de Bot2014). Therefore, the expected contribution of internal and external factors is unclear in the context of the present study. Furthermore, the learners in our study are older at the onset of formal instruction, which could also impact the results.

Inductive reasoning ability (a measure of fluid intelligence) is positively related to foreign language learning. Csapó and Nikolov (Reference Csapó and Nikolov2009), Nikolov and Csapó (Reference Nikolov and Csapó2018) and Ranta (Reference Ranta and Robinson2002) found a significant contribution of inductive reasoning ability to adolescents’ language proficiency. For working memory (phonological short term memory and verbal working memory) results are mixed. Kormos and Sáfár (Reference Kormos and Sáfár2008) found an effect of phonological short-term memory for beginners but not for pre-intermediate learners of English. They did however find that verbal working memory explained a substantial part (30%) of the variance in learners’ overall test scores. Michel et al. (Reference Michel, Kormos, Brunfaut and Ratajczak2019) only found a limited effect of working memory on 11–14-year-olds’ writing skills. Cheung (Reference Cheung1996), Gathercole and Masoura (Reference Gathercole and Masoura2005), and Service and Kohonen (Reference Service and Kohonen1995) investigated L2 vocabulary learning in young adolescent learners. They found that phonological short-term memory plays a role in L2 vocabulary acquisition, especially in low proficiency learners. As the participants in our study have just started formal instruction and are expected to be proficient at the A2-level of the CEFR (basic user) at the time of the study, we hypothesize that both analytic reasoning skills and working memory will play a role in L2 learning.

Prior knowledge, both L1 vocabulary knowledge and prior L2 knowledge, seems to positively impact learners’ language proficiency (Jaekel et al., Reference Jaekel, Schurig, Florian and Ritter2017; Puimège and Peters, Reference Puimège and Peters2019; Sun et al., Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Tendeiro and De Bot2016; Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and De Bot2015). We hypothesize this will also be the case in our study. Various studies have shown that length of instruction has a positive impact on L2 proficiency (Muñoz, Reference Muñoz2011, Reference Muñoz2014; Peters et al., Reference Peters, Noreillie, Heylen, Bulté and Desmet2019, Unsworth et al., Reference Unsworth, Persson, Prins and De Bot2015). The same goes for out-of-school exposure. Recent studies looking into the role of out-of school exposure in L2 learning have consistently shown that out-of-school exposure positively influences young learners’ L2 English proficiency (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a; Puimège & Peters, Reference Puimège and Peters2019; Sylvén & Sundqvist, Reference Sylvén and Sundqvist2012). Therefore, we believe that this external factor will also impact L2 learning in our study.

5. Method: participants, instruments, procedure

5.1. Participants

The participants in this study were 107 children who were tested twice, the first time in the last year of primary school (age 10–12) and a second time two and a half years later at the end of the second year of secondary school (age 13–14). The children are a subset of a larger group who were tested at the end of primary school (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a). All children had changed schools between the two tests. Therefore, we could only track about 1 in 7 of the 800 children who took part in the study at time 1. They came from 31 different primary schools and were in 53 different secondary schools at the time of the second test. Overall, the results for the language tests at time 1 were slightly higher for the subgroup than for the larger group though there was still considerable variability between the learners (see 6.1). This was to be expected as children with a lower test score at time 1 might be less inclined to take part in the second phase of the study. The sample consisted of 56 boys and 51 girls. At the first measurement 16 children were 10 years old, 86 children were 11 years old, 2 children were 12 years old and 3 did not report their age. At the second measurement 61 children were 13 years old, 45 were 14 years old and one child did not report her age. 94 children spoke only Dutch at home, 12 children reported they also spoke another language at home, and one child did not report her home language.

All children were attending school in Flanders, where the language of instruction is Dutch. As English lessons are not part of the set curriculum in primary school, only six children reported they had received some kind of formal instruction before the start of secondary education (e.g., extracurricular English classes).

The national curriculum states that the children's overall language proficiency at the end of the second year of general secondary education should be at CEFR-level A2, which means that they can communicate in simple and routine tasks requiring a direct exchange of information on familiar and routine matters (Council of Europe, 2001). Schools can choose to realise these objectives in one or two years. 57 children reported they had had 1 year of formal English instruction (about 60–70 hours), 44 children reported they had received 2 years of English instruction (about 120–140 hours), and six children had received more than two years of instruction (cf. supra). Generally, schools organise two 50-minute periods of English lessons per week (regardless of the number of years of instruction).

5.2. Instruments and procedure

English assessments

The children's English receptive vocabulary knowledge was measured at both measurements with the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test (PPVT) 4, form A (Dunn & Dunn, Reference Dunn and Dunn2007). During the first time of testing, we tested the first 120 items (10 sets of 12 items) of the PPVT. For each item children listened to a recorded spoken word and had to select the correct picture out of four. By using a recording, we made sure that all children heard the exact same pronunciation of the words. For the second measurement point, we added two sets (24 items) to avoid a ceiling effect and tested 144 items. Goriot et al. (Reference Goriot, van Hout, Broersma, Lobo, McQueen and Unsworth2018) warn about L1 effects when using the PPVT. As the number of cognates might influence the chance of a number of correct and wrong answers in a set, we tested all the items with all the participants and did not stop the test when 8 words in a set were wrong as is suggested in the PPVT manual.

The first data collection also involved a proficiency test, the Cambridge English Test for Young Learners: Flyers (Cambridge English Language Assessment, 2014), which consisted of three subtests measuring children's listening skills, speaking skills and reading and writing skills at an A2-level (CEFR). There were strong correlations between the four subtests (vocabulary and the three skills tests). A principal component analysis after the first data collection indicated that all four subtests largely measured the same proficiency component (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a). Therefore, we decided to only use the receptive vocabulary test and the speaking test, which proved to be the most challenging of the skills tests at time 1, as measures for overall language proficiency at the second data collection, leaving us with more opportunity to measure individual differences.

The speaking test used during the second data collection consisted of 3 different activities which were also used in the first data collection. The first activity was an information gap activity, the second activity was a picture description task and the third activity was a short interview. In the first data collection the participants did a fourth activity. This was a “spot the differences” activity, which did not involve a lot of production from the test taker. We therefore left it out in the second data collection. All speaking tests were done individually with an examiner and were recorded. All recordings were scored by two raters who used a rubric to assess the children's overall performance on four different components: vocabulary, grammar, pronunciation and interactive communication. The rubric was adapted from rubrics made available by Cambridge Language Assessment for other A2-level tests (see Appendix 1, Supplementary Materials).

Questionnaire

The children filled in a questionnaire at data collection 1 and 2. This questionnaire asked about background variables (such as age, gender, language background) and also asked in detail about the children's daily out-of-school exposure to English. The second questionnaire also contained questions about length of instruction and type of education (see Appendix 2, Supplementary Materials).

Cognitive variables and Dutch vocabulary knowledge

At the first measurement time, we could only measure the children's language proficiency and out-of-school exposure due to the large sample size (800 participants) and the fact that the wide range of language tests already took up quite some time. Because we were also interested in the role of internal individual differences in L2 learning, we added three tests measuring internal differences at the second measurement time. These were analytic reasoning ability, working memory and Dutch vocabulary knowledge. To measure these three constructs, subtests from the Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children V, Dutch version (WISC-V NL, Wechsler, Reference Wechsler2017) were used. The test battery is meant to measure general intelligence in Dutch-speaking children age 6–17 and consists of 14 subtests.

Analytic reasoning ability was measured with the matrix reasoning subtest. The children received an incomplete matrix or series and had to select a visual (four or five options were given) to complete the matrix or series. Children earned one point for every correct answer (maximum = 32 points). The test finished after 32 items or three consecutive wrong answers.

To measure working memory span we used the digit span task. This task consists of three subtasks: a forward digit span task (the child repeated a series of numbers in the same order it heard the numbers), a backward digit span task (the child repeated the numbers in reverse order) and a sort digit span task (the child repeated the numbers from the lowest to the highest number). The first task is a test of phonological short-term memory; the other two are complex verbal memory tasks. The maximum score for each subtest was 18 (nine items of increasing length with two series per item and one point per correct series) and the maximum total score was 54. Each subtest ended when the two digit series of a particular length were repeated incorrectly.

Finally, the children took the Dutch vocabulary test of the WISC-V NL. The first four items were presented as pictures, which had to be named with a Dutch word. The remaining 25 test items were written words, which had to be defined/described, by the test taker. The maximum score for the first four items was 1, for the other items the maximum score was 2 for a correct answer, 1 for a partial answer and 0 for an incorrect answer. The manual described which answers should be considered correct, partially correct and incorrect. There were 29 items, with a maximum score of 54. The test stopped when 3 consecutive items were answered incorrectly.

6. Results

6.1. Language proficiency

The results of the English language tests at both time points can be found in Table 1 and Figure 1. In order to be able to fully interpret the results of the vocabulary test it is important to know the number of cognates in the test at time 1 (54 cognates out of 120 items) and time 2 (62 out of 144 items). We calculated the formal similarity between the written item and its translation equivalent using normalized Levenshtein distance (Schepens et al., Reference Schepens, Dijkstra and Grootjen2012) and categorized words with normalized Levenshtein distance >.50 as cognates. The results in Appendix 3 Table S1 and Figure S1 (Supplementary Materials) confirm that cognates are easier to learn than non-cognates but at the same time show that some learners also obtained high scores for the vocabulary test without cognates. We also looked into the test results for the monolinguals (n = 95) and the multilinguals (n = 12) separately (Appendix 3, Table S2, Supplementary Materials). We found similar results for both groups. As the group of multilinguals is rather small, we only calculated descriptive statistics. The language tests used at time 1 had a high reliability: listening (α = .86), reading and writing (α = .89), receptive vocabulary (α = .91) and speaking (interrater reliability r = .89) (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a). Similar reliabilities were found for the language tests taken at time 2. The receptive vocabulary test, which contained 24 extra items, had a reliability of α = .95. All speaking tests were corrected by two raters. Interrater reliability was r = .89.

Fig. 1. Histograms for the different language tests at test times 1 and 2.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics language tests at test times 1 and 2.

To answer the first research question, we performed a t-test comparing the percentage scores for receptive vocabulary at times 1 (120 items) and 2 (144 items). The results showed that the learners performed significantly better on the second test with a large effect size (t(106) = 13.03, p < 0.001, d = 0.92). When comparing the scores on the first 120 items, which were all tested at both time points, the effect is even larger (t(106) = 16.90, p < 0.001, d = 1.27). The children's speaking skills also significantly improved between the two test times (t(104) = 13.96, p < 0.001, d = 1.16).

The second research question asked how the variability between learners changed after the onset of instruction. To answer this research question, we first looked at the variances at both time points. The variance in percentage scores for the vocabulary test at time 1 was 208.7 whereas the variance in percentage scores for the vocabulary test at time 2 was 121.7. A Levene test showed that the difference between the variances at test time 1 and 2 was significant (F(1, 212) = 8.93, p = 0.003). A similar result was found for the speaking test. The variance in speaking test scores at time 1 was 45.7, the variance at time 2 was 16.0. A Levene test again showed that this difference is significant (F(1, 210) = 28.15, p < 0.001). The density plots in figure 2 show both the children's overall improvement and the decrease in variance for both tests at time 2. These plots also show that part of the decrease in variance was due to a ceiling effect, because the test could not measure higher levels. This was particularly true for the speaking test.

Fig. 2. Density plots showing vocabulary and speaking test scores at times 1 and 2.

The different language tests were highly correlated both within and across time points (Table 2). We ran two principal component analyses (one for the tests taken at time 1, another for the tests taken at time 2). The PCA for the tests taken at time 1 shows that all language tests loaded on one component: language proficiency time 1. The KMO confirmed the sampling adequacy for the analysis (overall MSA: .86, MSA for individual items > .82). The correlation matrix (Table 2) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (p < .001) indicated that the correlations were large enough for principal components analysis. The analysis indicated that the first component already explained 87% of the variance (the factor loadings were .93 for the receptive vocabulary test, .91 for the listening test, .95 for the reading and writing test and .94 for the speaking test). The language tests at time 2 were analysed in another PCA, with similar results; although the overall MSA was only .50, which was also the MSA for the individual items. The correlation matrix (Table 2) and Bartlett's test of sphericity (p < .001) indicated that the correlations were large enough for principal components analysis. The first component already explained 87% of the variance (the factor loadings were .93 for the receptive vocabulary test and .93 for the speaking test). The PCA again shows that both tests load on one component: language proficiency time 2. For ease of reference, we will continue using the term “proficiency”, although we alert the reader to the fact that the PCA at time 2 is based on two elements of language proficiency only – receptive vocabulary and speaking skills – and that this proficiency should be understood as proficiency for these two elements.

Table 2. Summary of correlations (Pearson's r) for scores on the different language tests. The diagonal gives the reliability of the test.

6.2. Individual differences

Two individual differences were measured with a questionnaire: length of instruction and out-of-school exposure. As mentioned in 5.1., only six children reported they had received a form of instruction prior to the start of secondary school, 57 children had received one year of formal English instruction and 44 children had received two years of instruction. The children were asked to report time spent daily on several types of out-of-school exposure (watching English television without subtitles, watching English television with subtitles, watching English television with subtitles in the home language, listening to English music, reading in English, using social media in English, gaming in English and speaking English). The percentage frequency of the children's exposure at times 1 and 2 can be found in the supplementary materials (Appendix 3, Table S3, Supplementary Materials). Figure 3 shows the evolution of time spent doing the different activities per day (0 = I don't do this, 1 = less than 30 minutes, 2 = 30 minutes – 1 hour, 3 = 1 hour – 1 hour and 30 minutes, 4 = 1 hour and 30 minutes – 2 hours, 5 = more than 2 hours). T-tests revealed a significant increase over time in the following types of exposure to English: watching English television without subtitles, watching English television with English subtitles, listening to English music, using social media in English and speaking English (cf. Appendix 3, Table S4, Supplementary Materials).

Fig. 3. Boxplots showing the differences in out-of-school exposure at times 1 and 2.

The internal individual variables were only tested at time 2. These variables were analytic reasoning ability, working memory and Dutch vocabulary knowledge – and they were measured with a matrix reasoning task, three digit span tasks and a vocabulary test respectively. Descriptive statistics for these tests can be found in Table 3.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics internal variables measured at time 2

Table S5 in Appendix 3 (Supplementary Materials) shows the correlations between all the individual differences. The table shows that the three types of exposure which significantly predicted overall language proficiency at time 1 – gaming, social media and speaking (cf. De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a) – were moderately but significantly correlated with the same activities at time 2. These three types of exposure at time 2 were also significantly intercorrelated. Watching English television without subtitles or with English subtitles at time 2 significantly correlated with nearly all other types of exposure but not with watching television with subtitles in the home language. This type of exposure was only significantly correlated with listening to music. Concerning the internal variables, we found the results for the matrix reasoning task correlated moderately with Dutch vocabulary knowledge. As expected, all three digit span subtasks were significantly intercorrelated.

6.3. How do individual differences influence language learning?

In order to answer the third research question, we first looked at the correlations between the individual differences, the children's prior knowledge at time 1 and the learners’ language proficiency at time 2 (cf. Table 4). There were strong positive correlations between L2 knowledge at time 1 (before instruction) and L2 knowledge at time 2. De Wilde et al. (Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a) found that gaming, using social media and speaking English were the main predictors for L2 English language proficiency in a large-scale study conducted at time 1. These types of out-of-school exposure also positively correlated with language measures at time 2. Reading English books was also positively correlated with L2 English proficiency (r = .33 for overall language proficiency). Correlations between L2 English proficiency and watching television were weaker; for watching television with subtitles in the home language the correlations were negative. Years of instruction was positively correlated with receptive vocabulary knowledge (r = .18) and even more so with speaking skills (r = .26). Dutch vocabulary knowledge was positively and significantly correlated with all L2 measures. The tests measuring analytic reasoning ability and working memory were not significantly correlated with L2 measures.

Table 4. Summary of correlations (Pearson's r) between the different measures of individual differences and the measures for language ability at time 2.

*** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

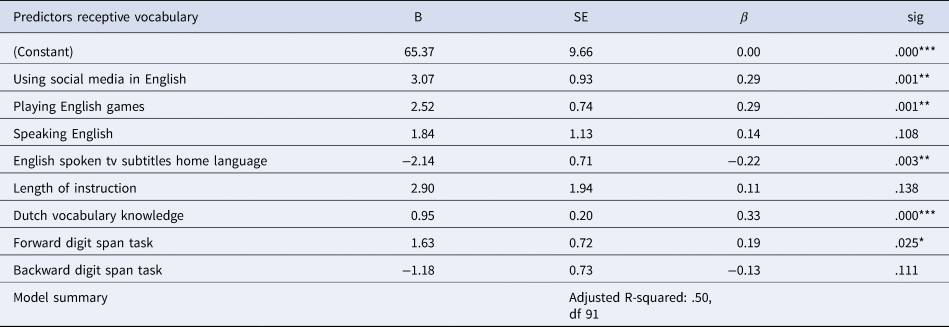

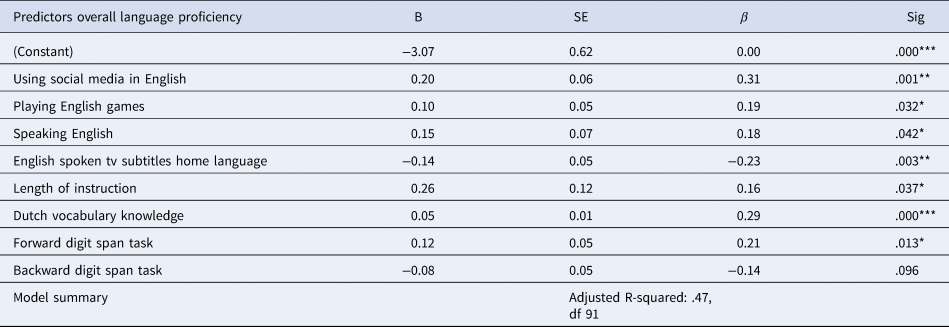

To investigate the interplay between overall language proficiency and the subskills (L2 English receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills) at time 2 and the various internal and external individual differences, we used backward regression. We first investigated the relationships without prior L2 knowledge. First, we added all the ID variables in the full model. Then, the best model was selected using the stepAIC function of the MASS- package (version 7.3–51.4, Ripley, Venables, Bates, Hornik, Gebhardt, Firth & Ripley, Reference Ripley, Venables, Bates, Hornik, Gebhardt, Firth and Ripley2013) in R (version 3.6.1., R Core Team, 2019). Missing values were deleted, leaving us with 99 participants. The best fitting models can be found in Tables 5a–c.

Table 5a. Results of the regression model for receptive vocabulary at time 2 (n = 99).

*** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

Table 5b. Results of the regression model for speaking at time 2 (n = 99).

*** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

Table 5c. Results of the regression model for overall language proficiency at time 2 (n = 99).

*** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

We also ran separate backward regression analyses for the internal and external variables using the same procedure. Results of the best fitting models can be found in Appendix 3, Tables S6a-c and S7a-c (Supplementary Materials). Individual differences which significantly predicted L2 receptive vocabulary in the final model were gaming, using social media, Dutch vocabulary knowledge and the forward digit span task – which had a positive relation with receptive vocabulary knowledge. Watching television with subtitles in the home language was also retained in the model but had a negative relation with receptive vocabulary knowledge. Together these variables explained 50% of the variability between learners’ L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge. External variables alone explained 40% of the variability (Table S6a, Supplementary Materials); internal variables alone explained 8% of the variability between learners’ L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge (Table S7a, Supplementary Materials). Three types of out-of-school exposure significantly predicted speaking at time 2. Using social media and speaking English had a positive influence; watching television with subtitles in the home language was negatively related with young learners’ speaking skills. Dutch vocabulary knowledge and the forward digit span task also positively impacted children's L2 speaking skills, as did length of instruction. The model explained 34% of the variability in learners’ speaking skills. External variables alone explained 27% of the variability (Table S6b, Supplementary Materials); internal variables alone explained 4% of the variability in learners’ L2 speaking skills (Table S7b, Supplementary Materials).

As we were also interested in the role of ID variables on overall language proficiency, we considered the relationship between individual variables and overall L2 English proficiency as measured by the PCA at time 2. Six variables had a positive impact on children's overall language proficiency: using social media, gaming, speaking English, length of instruction, Dutch vocabulary knowledge and the forward digit span task. Watching television with subtitles in the home language was negatively related to overall language proficiency. The model explained 47% of the variability in the learners’ overall language proficiency. External variables alone explained 36% of the variability (Table S6c, Supplementary Materials); internal variables alone explained 7% of the variability in learners’ L2 speaking skills (Table S7c, Supplementary Materials).

All models changed considerably when we added prior L2 knowledge as measured at time 1. The best model for vocabulary knowledge (adjusted R2 = .73) involved five variables (see Table 6a) but only three were significant (prior L2 knowledge, gaming, listening to music). Prior L2 knowledge alone explained 69% of the variability in the model. Similar results can be found for speaking skills (Table 6b), where the best model contained three predictors (R2 = .59) and prior knowledge alone explained 58% of the variability, and for the overall language proficiency component (Table 6c), where three predictors made up the best model (R2 = .74) but only one predictor, prior knowledge was significant and explained 72% of the variance. Figure 4 shows the relationship between prior and current L2 knowledge.

Fig. 4. Scatterplots showing the relationship between prior and current L2 knowledge.

Table 6a. Results of the regression model for receptive vocabulary knowledge with prior knowledge included (n = 99).

*** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

Table 6b. Results of the regression model for speaking skills with prior knowledge (n = 99).

*** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

Table 6c. Results of the regression model for overall language proficiency with prior knowledge (n = 99).

*** p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

7. Discussion

In this study we tested over 100 Dutch-speaking children on their knowledge of L2 English receptive vocabulary and speaking skills after having attended 1–2 years of English classes. A particularly interesting feature of our study was that all children had been tested two years earlier (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a), before formal L2 English education started. This allowed us to study the interaction between classroom language teaching and prior contextual language knowledge.

Our first question was whether the children's L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills would improve after the onset of instruction. Our data showed a standardized effect size of d ≈ 1.1. This is a big difference, given that the typical effect size in psychology is d = .4 (Stanley, Carter & Doucouliagos, Reference Stanley, Carter and Doucouliagos2018). For the purpose of comparison we would like to note that a therapy with an effect size of d = 1 is considered a very successful therapy with 72% of the patients being treated fruitfully (Norcross & Lambert, Reference Norcross and Lambert2018). The improvement was so large that the speaking test we used showed a ceiling effect because it only tested language skills up to the A2-level. Part of the improvement was due to formal education, given that children with two years of English classes performed better than children with one year of English classes. However, the correlation between years of instruction and English proficiency was rather low (r = .26 at most) and years of instruction tended to have more impact on speaking skills than on vocabulary knowledge. This could be because many different aspects of language are involved in speaking activities (e.g., productive vocabulary knowledge, grammar knowledge, pronunciation, effective use of strategies, etc.).

The second question we had was what would happen with the variation within learners’ L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills when formal classroom instruction was introduced. Officially, the minimal aim of the Flemish national curriculum for English at the time of the second measurement is that all children have reached the CEFR A2-level. If this were all that took place, the best students would learn nothing new (as they already reached the A2-level by the end of primary school on the basis of contextual learning), whereas the worst students would be brought to the same level. As can be seen in Figure 4, this is not what happened: differences in receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills after 1–2 years of schooling correlated strongly with the differences in prior knowledge. There is some evidence that the increase was larger for children with low prior knowledge; but we must be very careful with this finding, as there was evidence for a ceiling effect in our tests (in particular, the speaking test). Until more data are collected, the most likely conclusion is that the effects of schooling and contextual learning are largely additional. There is no evidence for a Matthew effect. The gap between the high and the low performers does not increase because of formal instruction.

When looking at the individual differences, we saw that the amount of out-of-school exposure to English increased from the age 10–11 to 13–14. The ‘English-only’ activities nearly all became more popular. Only time spent on watching television with subtitles in the home language stayed the same.

English L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills in 13–14-year-olds were predicted by the use of social media, gaming, speaking English, length of instruction, vocabulary size in L1 (Dutch) and phonological short-term memory (measured with the forward digit span task). In all models, watching television with subtitles in the home language impacted L2 knowledge negatively. Even though this might seem contrary to what has been found in previous research (e.g., Lindgren & Muñoz, Reference Lindgren and Muñoz2013), this need not be the case. Our findings do not contradict the possibility that contextual language learning takes place while watching television with subtitles in the home language. They may point to the fact that lower proficiency learners prefer input that is supported by L1 subtitles, whereas more proficient learners prefer ‘English-only’ input. In one of the models (cf. Table 6a) listening to English music had a negative impact on L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge. This is something we also found in our previous research (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a) and it could be explained by the fact that listening to music or even singing along does not require actual language comprehension.

We also investigated the role of internal factors. Dutch vocabulary knowledge contributed to L2 proficiency, which shows that children rely on everything they already know when learning something new (both concerning form and conceptual knowledge). The results further showed that cognates are easier to learn than non-cognates. This is in line with previous findings by De Wilde et al. (Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020b), Goriot et al. (Reference Goriot, van Hout, Broersma, Lobo, McQueen and Unsworth2018) and Puimège and Peters (Reference Puimège and Peters2019).

We investigated two more cognitive variables in this study: working memory and analytic reasoning ability. Only the forward digit span task (measuring phonological short term memory) significantly predicted L2 proficiency, which is in line with the hypothesis that phonological short-term memory plays a critical role in L2 vocabulary acquisition (Baddeley, Gathercole & Papagno, Reference Baddeley, Gathercole and Papagno1998; Gathercole & Masoura, Reference Gathercole and Masoura2005; Kormos & Sáfár, Reference Kormos and Sáfár2008).

Overall, the contribution of the internal factors is rather small (R2 between .04 and .08) compared to the contribution of external factors (R2 between .27 and .40). This finding is in line with a study by Sun et al. (Reference Sun, Steinkrauss, Wieling and de Bot2018a) with very young learners. The authors found that, in an input-poor environment, external factors explained more variance. The environment in our study is not necessarily ‘input-poor’, as there is easy access to English for our learners. But the exposure is largely voluntary, so that the actual amount of exposure can differ substantially between the learners. In such a learning context, it is maybe not surprising that differences in input explain the bulk of variance in early L2 proficiency. The studies which investigated the role of cognitive variables in young learners (see 3.3) showed mixed results, depending on the learning context. The findings in this study suggest that the learning context and the availability of the L2 have a much larger impact on L2 learning than cognitive variables, at least at the early stages of L2 learning.

As this study was a longitudinal study, we also have information about the children's prior L2 knowledge. As discussed above, this variable was by far the best predictor of L2 competence at time 2. When we added the variable to the models, the predictive effects of all other variables tended to disappear, including length of instruction. Depending on the dependent variable, prior L2 knowledge alone predicted between 58 and 72 percent of the variability between learners, indicating that the main and maybe even sole predictor of L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills at time 2 was L2 proficiency at time 1. This was also true when receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills were combined in a single proficiency component by means of principal component analysis. The big effect of prior L2 knowledge is further evidence that for the early stages of L2 English acquisition, contextual learning is very important in a context where English is readily available and children are motivated to learn the language. Indeed, nearly all children in our previous study (De Wilde et al., Reference De Wilde, Brysbaert and Eyckmans2020a) showed a positive attitude towards the language. This attitude seems to be stable as over 95% of the learners were still positive towards English at time 2. The additive effects of contextual learning and formal learning further suggest that the two types of knowledge have largely independent contributions to language proficiency.

This study also has some limitations. First of all, as the participants were in over 50 secondary schools, we were not able to take the school's approach to teaching English into account. The assumptions we make about explicit learning and focus on form are based upon what we see in course books and what can be found in the (national) curricula. An in-depth investigation of the effects of particular approaches would be interesting for future research. Future research could also look into the effect of affective variables. We only asked children about their attitude but a closer look into different aspects of motivation might offer extra insights. Finally, measures of cognitive variables at time 1 would have been interesting as well. This would have given us the opportunity to look at the importance of these variables prospectively. In the present study, this was not possible for practical reasons.

Other limitations concern the language tests. Even though grammar was taken into account in the assessment of the children's speaking skills, the study did not include a separate grammar test. Learning the grammar of a foreign language is typically associated with schooling. So, we might have found a bigger effect of instruction here.

A second limitation of the language tests we used is that the speaking test only measured speaking skills up to CEFR-level A2. This is the level most children are supposed to reach by the end of the second year of secondary school, which indeed turned out to be the case. Unfortunately this meant that we could not probe higher levels of knowledge. For future research, a more advanced test will be needed.

Finally, although our previous research suggested that all L2 skills heavily load on a single proficiency component, it would be good to verify our findings at time 2 with more tasks and language skills, to make sure that the results generalize to functions other than receptive vocabulary and speaking skills.

8. Conclusion

This longitudinal study investigated children's L2 English receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills at two points in time, before the start of formal instruction and after one or two years of instruction. Results show that overall learners’ receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills improve over time but that the introduction of instruction leaves the differences in prior knowledge largely unaffected. There was some evidence that the performance of children with low prior knowledge increased slightly more than the performance of children with high prior knowledge; but the evidence is hindered by the ceiling effect we observed, particularly in the speaking test. The main predictor of children's L2 receptive vocabulary knowledge and speaking skills at time 2 was their L2 prior knowledge as measured at time 1. This finding shows that contextual language learning plays a prominent role in English L2 learning in a country where English is omnipresent and has a high status.

Acknowledgements

We thank Geert De Meyer, Philip O'Neill, Ryan Reynaert, our students and colleagues for help with testing. We thank the schools, the teachers, the pupils and their parents for participating in the project. This research was supported by the FWO (Research Foundation Flanders, special PhD-fellowship 1902020N) and Artevelde University of Applied Sciences in the context of the PWO-project False Beginners.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728920000747

List of supplementary materials

Appendix 1: Rubric used to assess speaking performance

Appendix 2: Children's questionnaire data collection 2

Appendix 3 : Supplementary tables and figures