Introduction

Traditionally, experimental examinations of switching between languages (codeswitching) in production were elicited from text presented in the laboratory, or studied in conversational dyads (for overviews, see Bullock & Toribio, Reference Bullock and Toribio2009; Kootstra, van Hell & Dijkstra, Reference Kootstra, van Hell and Dijkstra2009). One limitation of work conducted over relatively short time spans is that the impacts of longer-term events and broader linguistic contexts are not easy to examine (Green, Reference Green2011). In contrast, the present study examines codeswitching in a more ecological, online context extending over a period of days.

Customary portrayals of language switching entail a cognitive mechanism whose function is to restrict output to a single language via a top-down mechanism such as executive control. The advantage accrued by cognates, words with similar spelling and meanings in two languages, and the facility with which cognates can serve as the locus of a switch between languages invites a more nuanced account (Broersma, Isurin, Bultena & De Bot, Reference Broersma, Isurin, Bultena, De Bot, Isurin, Winford and De Bot2009). Work on cognates from corpora (e.g., Broersma, Carter, Donnelly & Konopka, Reference Broersma, Carter, Donnelly and Konopka2019; Broersma & De Bot, Reference Broersma and De Bot2006) revealed that not all words are equally likely to be included in a codeswitch. Bilinguals can initiate a switch between languages when performing tasks such as naming pictures aloud (Gollan, Schotter, Gomez, Murillo & Rayner, Reference Gollan, Schotter, Gomez, Murillo and Rayner2014b). However, both material-cued and experimenter-induced codeswitches seem to differ from participant-initiated (voluntary) switches, with respect to potential cost to the speaker (Gollan, Kleinman & Wierenga, Reference Gollan, Kleinman and Wierenga2014a). More recently, accounts of codeswitching have begun to make contact with psycholinguistic and sociolinguistic experience rather than focusing solely on language control.

While laboratory studies of codeswitching typically entail manipulations of language imposed by instruction or cues in the materials and generally measure an aspect of production or of comprehension at the level of the word, some work shows a coordination between speaker and listener (e.g., Fricke, Kroll & Dussias, Reference Fricke, Kroll and Dussias2016). Importantly, preparation for an anticipated codeswitch can be detectable to the listener from the consequences of the articulatory behavior of the speaker even before the advent of the language switch defined by word choice. These results show that not only can bilingual speakers alter phonological aspects of their production prior to shifting lexical choices from one language to another, but bilingual listeners can exploit phonological or morphosyntactic cues of an upcoming codeswitch while comprehending another (Fricke et al., Reference Fricke, Kroll and Dussias2016; Guzzardo Tamargo, Valdés Kroff & Dussias, Reference Guzzardo Tamargo, Valdés Kroff and Dussias2016; Shen, Gahl & Johnson, Reference Shen, Gahl and Johnson2020; Valdés Kroff, Dussias, Gerfen, Perrotti & Bajo, Reference Valdés Kroff, Dussias, Gerfen, Perrotti and Bajo2017). The coordination across conversants and processes is impressive given the locus of a language switch may be distributed so that the phonological and lexical properties of the upcoming language switch do not necessarily arise concurrently.

Aspects of individual speaker experience and the social context in which communication arises also influence the tendency to codeswitch (e.g., Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo & Kroll, Reference Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo and Kroll2019; Declerck & Philipp, Reference Declerck and Philipp2015; Fricke et al., Reference Fricke, Kroll and Dussias2016; Shen et al., Reference Shen, Gahl and Johnson2020; Valdés Kroff et al., Reference Valdés Kroff, Dussias, Gerfen, Perrotti and Bajo2017). When preparing a response, bilinguals are sensitive to a host of less purely lexical factors such as the language proficiency of the other speaker (Kaan, Kheder, Kreidler, Tomić & Valdés Kroff, Reference Kaan, Kheder, Kreidler, Tomić and Valdés Kroff2020; Kapiley & Mishra, Reference Kapiley and Mishra2019), the social context including the conventions for codeswitching in a particular community (Valdés Kroff et al., Reference Valdés Kroff, Dussias, Gerfen, Perrotti and Bajo2017) and aspects of status (Tenzer & Pudelko, Reference Tenzer and Pudelko2015). Although power relations are less likely to play a prominent role across variable online codeswitching contexts (Barasa, Reference Barasa2016), it now seems that an account of switching based solely on cognitive factors and the conditions that give rise to difficulties suppressing words in the non-target language needs to encompass opportunity-specific aspects of socially complex language use.

The present study exploits social media, specifically online texting as an underexplored context in which to gain new insights into the conditions that are most amenable to codeswitching (Barasa, Reference Barasa2016). Computer Mediated Communication (CMC) as by Twitter, when compared to conventional written communication, tends to be more informal with less deliberate planning than other types of written communication (Dorleijn & Nortier, Reference Dorleijn, Nortier, Bullock and Toribio2009). Further, CMC may fail to include mutual visibility and simultaneous turntaking, conditions that enhance the coordination typical of spoken communication (Galati, Dale & Duran, Reference Galati, Dale and Duran2019). Our focus is a social network site to communicate about Hurricane Irma. Of particular interest is the degree to which the tendency to codeswitch can be predicted from the statistical tendencies across many single speakers to prefer one language over another or to switch between them (Beatty-Martínez et al., Reference Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo and Kroll2019; Beatty-Martínez & Dussias, Reference Beatty-Martínez and Dussias2017; Guzzardo Tamargo et al., Reference Guzzardo Tamargo, Valdés Kroff and Dussias2016; Kootstra, van Hell & Dijkstra, Reference Kootstra, van Hell and Dijkstra2012).

We introduce tweeting history to identify people with command of two languages (bilinguals). We define a bilingual's language preference from that individual's proportion of total tweets in each language within a designated communicative setting (see Treffers-Daller, Reference Treffers-Daller2019 for an overview). Further, rather than relying on self-reports of proficiency, we consider as balanced bilinguals those with approximately equal (between 35%-65% of) total tweet production in English and Spanish. Another innovation is that the exchange is within a community, not within fixed pairs. Particularly novel in our study is the exploration of language codeswitching in conjunction with lexical diversity based on variation among individual words and their relative frequency of appearance in tweets. Lexical diversity (LD) is a measure of vocabulary richness based on a framework from information theory and describing uncertainty reduction. LD encompasses both a word's relative frequency and the distribution of relative frequencies across words expressed in bits of information. It is to be preferred over a simple type-token ratio of vocabulary richness because it is less influenced by sample size (Zhang, Reference Zhang2014). We start with the hypothesis that 1) the tendency to codeswitch in online communication depends on an individual's relative preference for a language as measured by a ratio of production in each language in successive tweets about a weather event in the Caribbean that extended over several days. We link conditions for codeswitching to 2) lexical diversity based on how often each word appears, such that varying probabilities reflect distinctly different patterns of word usage. To anticipate, we tie patterns of codeswitching not only to language preference but also to vocabulary richness within those comments and posts. We ask whether the pressure for reduced uncertainty in communication, as arises when lexical diversity among strongly valenced words is high, can be associated with the conditions amenable to a codeswitch.

In previous work on monolingual online communication (Barach, Shaikh, Srinivasan & Feldman, Reference Barach, Shaikh, Srinivasan and Feldman2018), for strongly valenced words (Warriner, Kuperman & Brysbaert, Reference Warriner, Kuperman and Brysbaert2013), we observed lower diversity for words with negative (e.g., SNAKE, BOMB) than with positive (e.g., CANDY, HUG) valence. We restrict our analyses to strongly valenced words and anticipate replicating lower lexical diversity when valence is negative than positive. With respect to conditions associated with a codeswitch, we ask whether lexical diversity for English before a codeswitch out of English (and into Spanish) and after a codeswitch (from Spanish) into English is greater than in tweets remote (± 10 tweets) from a codeswitch. Differentiated word usage would suggest that communicative precision at a codeswitch as indexed by vocabulary richness creates an opportunity that attenuates constraints against mixing languages (Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres & Dussias, Reference Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres and Dussias2020).

Methods

Data collection

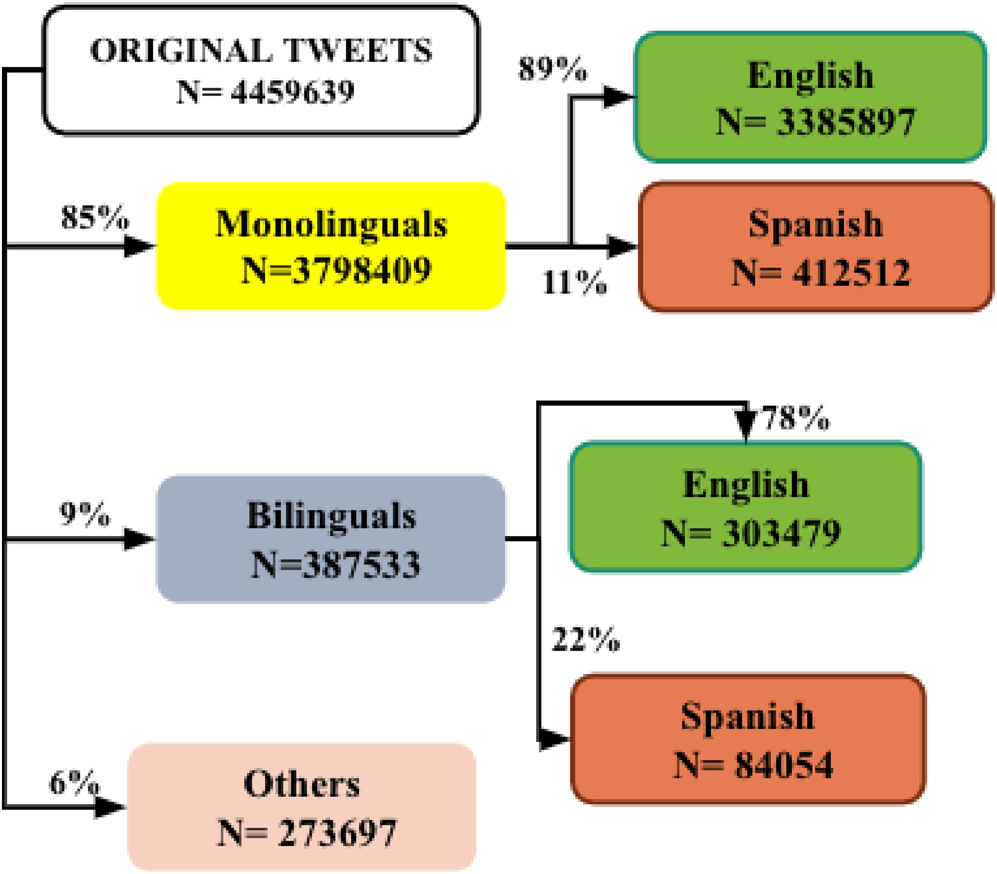

All tweets incorporated into the corpus included hashtags that referred to Irma, a catastrophic Category 5 hurricane in August 2017 that impacted both English and Spanish speaking countries. The specifics of data filtering are depicted in Figure 1. We used an individual's posting history during the course of the event and Twitter's language detection API to identify those people who communicated in more than one language and computed a posting history ratio from the number of tweets in English/total in English + Spanish. Accordingly, the original bilingual corpus consisted of nearly 189,000 tweets contributed by 1040 different people. We included in the Irma bilingual corpus only speakers of English and Spanish who contributed 50 or more tweets (range 50-3521) of which at least 1% were in their non-dominant language. Finally, for the 87% of posts from bilinguals that included geolocations, we computed percent of tweets by language by storm day by location. There was a suggestion that the percent of tweets on the storm path changed by day but only slightly by language (Figure S1A, Supplementary Materials). The percent of total tweets in English changed little over storm day and associated storm location (Figure S1B, Supplementary Materials). In each time frame on the storm path and combined over geolocations, there were more tweets in English than in Spanish.

Fig. 1. Distribution of original tweets across monolingual and bilingual speakers in English/Spanish in the Hurricane Irma corpus. “Others” includes tweets from bilinguals with French as one of their languages and trilinguals with French as well as monolinguals whose language could not be identified automatically by Twitter API.

Codeswitches within a noun phrase can provide interesting insights into how switches arise (Beatty-Martínez, Valdés Kroff & Dussias, Reference Beatty-Martínez, Valdés Kroff and Dussias2018). However, because many were informative and that function can make tweets less informal (Barasa, Reference Barasa2016), codeswitches within a tweet were extremely rare (4.23%) and occurred mainly as direct translations such as “Current location of Hurricane Irma. Localización actual del Huracán Irma” or as instances (54) of switches from a Spanish article to the English noun el/del hurricane or the reverse such as the huracán (36). Therefore, analyses in the present study focus on codeswitches between tweets.

We used the time stamp for each tweet to determine both the day and the order in which tweets were posted. From the sequence of tweets, we determined where a switch between languages occurred, which speaker initiated it and the number of times each speaker produced a tweet in a language different from the immediately prior tweet. We define codeswitching within the tweet sequence but without preserving speaker identity, therefore we cannot ascertain definitively which recent tweet a bilingual was responding to and whether its author also qualified as a (balanced) bilingual. Examples of codeswitches appear in Table 1. One implication of defining codeswitches in this way is that it disrupts the symmetry of switches into and out of English and Spanish.

Table 1. Examples of successive tweets with a codeswitch.

Participants

As described above, we used a speaker's percent of total original tweets (no retweets) in English as a measure of language preference for English (or Spanish). Based on tweeting history, there were many more tweeters (“speakers”) with strongly asymmetric language preference and, typically, English was the stronger language. The distribution of tweets by a user's degree of preference for either English or Spanish is depicted in Figure 2.

Fig. 2. Median tweets per tweeter at deciles indicating progressively stronger degrees of preference for English.

Results

The codeswitching analyses are based on balanced bilinguals with approximately equal numbers of tweets in each language. More specifically, the ratios of English to total (English plus Spanish) tweets ranged between 31 and 70 percent. A codeswitched tweet arose when a balanced bilingual failed to match the language (English, Spanish or French) of the single previous tweet as defined by its time stamp.

To examine the relation between language preference and switch tendency, we computed proportions of codeswitches as a function of language of prior and current tweet. Unsurprisingly, there was a significant main effect of language preference, demonstrating that people with a stronger preference for English had lower proportions of switches [F(2,79) = 5.57, p < .01]. Direction of codeswitch also was significant [F(2.05, 161.94) = 2886.74, p < .001]Footnote 1. Due to greater prevalence of English tweets in the full corpus, the opportunity for, and thus the percent of total switches – from English into Spanish – was higher overall than in the reverse direction. Most striking was the significant interaction between degree of preference for English and direction of language switch [F(4.10, 161.94) = 35.21, p < .001] (Figure 3).

Fig. 3. Proportion of tweets with switches (and CI) at approximately matched (35%, 44% and 64%) levels of language proficiency based on language preference (English or Spanish) for four switch directions: Spanish to English; Other (Spanish or French) to English; English to Spanish; Other (English or French) to Spanish.

Simple regressions (see Figures 4 A & C respectively) revealed that the proportion of switches from English into Spanish decreased as English preference (treated continuously) strengthened while the proportion of switches from Spanish into English increased as English preference strengthened. Switches from other languages (e.g., French) into English and Spanish were similar but the relations were reduced (see Figures 4 B & D). In essence, systematic influences of language preference on direction of switches are detectable in the Irma online bilingual setting.

Fig. 4. Proportion of tweets with language switches by language proficiency based on language preference for four directions. A) English to Spanish; B) Other (English or French) to Spanish; C) Spanish to English; D) Other (Spanish or French) to English.

Our second venture into online language switching behavior focuses on lexical diversity among balanced bilinguals. Our method relies on properties of the distribution of individual word frequencies with bootstrapping and confidence intervals to assess differences between distributions. We borrow the method of Moscoso del Prado Martín (Moscoso del Prado Martín, Reference Moscoso del Prado2017; Moscoso del Prado Martín & Du Bois, Reference Moscoso del Prado and Du Bois2015) adapted from an information-theoretical framework (Shannon, Reference Shannon1948) that is widely accepted in biology (Gotelli & Chao, Reference Gotelli, Chao and Levin2013) to compare uncertainty. The measure of diversity is estimated from the log2 of the inverse of probability (bits) and the sum of the number of bits over all words weighted for their probability. Similar measures of uncertainty have been applied successfully to other aspects of bilingual communication (Feldman, Aragon, Chen & Kroll, Reference Feldman, Aragon, Chen and Kroll2017; Gullifer & Titone, Reference Gullifer and Titone2019) as well as other language domains (Hendrix & Sun, Reference Hendrix and Sun2020). Comparisons are easiest to interpret when distributions are similar in size (DeDeo, Hawkins, Klingenstein & Hitchcock, Reference DeDeo, Hawkins, Klingenstein and Hitchcock2013).

Our focus is the frequency distribution of highly-valenced English words and whether lexical diversity among balanced bilinguals tends to increase around a switch between languages. We analyze only those words whose ratings in Warriner et al. (Reference Warriner, Kuperman and Brysbaert2013) fall in the most extreme positive or negative 25%. Typically, lexical diversity is disproportionately attenuated when valence is negative, so we separate analyses by valence (Barach et al., Reference Barach, Shaikh, Srinivasan and Feldman2018; Barach, Shaikh, Srinivasan, Hormes & Feldman, Reference Barach, Shaikh, Srinivasan, Hormes and Feldman2019). In Figure 5, English tweets show more lexical diversity for positively than for negatively valenced words in this event. There were about one eighth as many strongly valenced words in Spanish as in English. Corpus size limitations in Spanish forced us to focus exclusively on word choices surrounding a codeswitch out of or into English

Fig. 5. Lexical diversity (and CI) in most extremely (25%) valenced words in English tweets immediately before or after a codeswitch and + /- ten tweets away.

Next, we ask whether lexical diversity varies systematically around a codeswitch relative to diversities collected at intervals of ten tweets away from each codeswitch (assuming no intervening switches). To form pairs of tweets at, versus remote, from a codeswitch, we identified an English tweet by a balanced bilingual participating in a codeswitch and found an English tweet by that same person ten tweets away. We assigned the two tweets to different corpora, targeted words with the 25% most extreme valence ratings and then computed lexical diversity close and far from the switch. Figure 5 shows that for positively as well as negatively valenced words, English lexical diversity adjacent to a codeswitch is greater than diversity when a switch is relatively remote. We emphasize that the analysis of lexical diversity around a codeswitches compares strongly valenced words from tweets by the same bilinguals.

Lexical diversity captures well differentiated word usage overall and is higher in monolinguals than in French–English bilinguals when they communicate in English (Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Aragon, Chen and Kroll2017). The prospects of a role for lexical diversity coordinated with codeswitching between languages is intriguing and invokes information theory. Codeswitching can be cognitively demanding, and costs can vary with immediacy of the switch (Gullifer & Titone, Reference Gullifer and Titone2019). Others have suggested that its cost may be offset by optimizing another aspect of communication (Beatty-Martínez et al., Reference Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres and Dussias2020). For example, reduced lexical diversity, like other variants of style matching (Abney, Paxton, Dale & Kello, Reference Abney, Paxton, Dale and Kello2014), can be a marker of better cooperation among speakers (Feldman et al., Reference Feldman, Aragon, Chen and Kroll2017). Previously undocumented is whether lexical diversity varies systematically in proximity to a codeswitch. Here, we report diversity differences with highly valenced words at, relative to, remote from, a switch in the context of a crisis event in a multilingual geographical area. Further, differentiated usage of strongly valenced words at a switch word is compatible with an emotional component to codeswitching (Williams, Srinivasan, Liu, Lee & Zhou, Reference Williams, Srinivasan, Liu, Lee and Zhou2020).

Discussion

We have identified a graded tendency for bilinguals who prefer to communicate in Spanish to initiate switches into Spanish in the context of a tweet corpus that is predominantly English. Further, this online behavior could not readily be demonstrated in a laboratory setting. At first glance, the prevalence of graded codeswitching into one's preferred language may seem superficially incompatible with switching data from comprehension and production tasks in the laboratory where, as a rule, the pattern of reaction times indicates that bilinguals find it more difficult to switch back into the L1 after speaking in the L2 (e.g., Gambi & Hartsuiker, Reference Gambi and Hartsuiker2016). Important to emphasize is that in the present study, 1) language switching encompasses successive tweets produced by different individuals, that 2) speakers differ with respect to language preference based on tweeting history within the same corpus rather than on self-ratings or another measure of proficiency, 3) more messages overall are in English than in Spanish and 4) compared to non-switch tweets by the same speaker within the same corpus, greater diversity among strongly valenced words characterizes the conditions under which codeswitching emerges.

People debate about the extent to which encountering people online is similar to and different from encountering people face-to-face (see Osler, Reference Osler2019). The question gains urgency during the time of a pandemic when many face-to-face transactions must occur remotely. Any analysis of online behavior has the potential to provide insights not only into linguistic structure but also into communication defined broadly enough to include coordination across participants. In the present study, we have focused on switching between language codes in the context of online communication in a crisis-related problem space whose time span differs in important ways from the conditions under which language can be investigated in the laboratory. Admittedly, we sacrifice many aspects of control and contributions of proficiency for greater ecological validity in order to extend patterns beyond face-to-face communication (Beatty-Martínez et al., Reference Beatty-Martínez, Navarro-Torres, Dussias, Bajo, Guzzardo Tamargo and Kroll2019). The tradeoff is that factors that are almost impossible to detect with weaker pressures to communicate become evident. Within these constraints, we have discovered that 1) among those who can be documented to text in two languages, the tendency to codeswitch is systematically related to language preference in prior tweet production in the same corpus by that same individual and that 2) lexical diversity increases around a codeswitch, creating conditions that seem to optimize communication by enhancing communicative precision while attenuating constraints against mixing languages.

Supplementary Material

For supplementary material accompanying this paper, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728921000122