Introduction

Governments and other organizations worldwide have begun to explicitly use behavioural insights to nudge people to make better choices as judged by themselves without reducing freedom of choice (Thaler & Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008). Nudging is used, for example, to encourage people to pay their taxes on time, to save more for retirement and to eat healthier. Nudges do not provide new information. Nor do they change economic incentives or take away choice options. To the contrary, they rely on findings from the psychological and behavioural sciences about how people interact with their environments when making decisions. Most nudges change these environments – called the choice architecture in behavioural parlance – in order to make it easier for people to choose the options they prefer.Footnote 1

With the major uptake of nudging in many governments and other organizations, a large and growing literature on the ethics of nudging has emerged (e.g., Hausman & Welch, Reference Hausman and Welch2010; Grüne-Yanoff, Reference Grüne-Yanoff2012; Rebonato, Reference Rebonato2012; Bubb & Pildes, Reference Bubb and Pildes2014). This debate has matured in recent years, and it is now possible to identify the most important and recurring arguments against and in favour of nudging. It has also become obvious that different nudges need different ethical considerations and that a nuanced, case-by-case assessment of the ethics of nudging is needed. The authors of Nudge, Thaler and Sunstein, engage in the debate on the topic. Sunstein has written a number of books and academic articles on the ethics of nudging (e.g., Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2014, Reference Sunstein2016b), and whenever Thaler signs a copy of the book Nudge, he signs with ‘Nudge for Good’, which is meant as a plea rather than an expectation (Thaler, Reference Thaler2015). Recently, Thaler added that we should ‘nudge, not sludge’ and avoid nudging for evil or making wise decision-making and prosocial activities more difficult (Thaler, Reference Thaler2018).

However, the meaning of the phrase ‘nudge for good’ may still not be obvious and salient for applied nudgers. The assessment of the ethics of a specific nudge often relies more on moral intuition than on a systematic assessment based on the most important dimensions covered in the literature on the ethics of nudging. Many nudgers aim to help individuals to make better decisions in an ethical way. But since policy-makers are usually busy and ethical questions can be complex, it is not straightforward for them to identify and solve ethical problems about whether a given nudge is ethically permissible or not.

The complexity of assessing the ethics of nudging is in stark contrast to how easy it has become to design effective nudge interventions relying on behavioural science frameworks such as MINDSPACE and EAST, popularized by the UK Behavioural Insights Team (Dolan et al., Reference Dolan, King, Halpern, Hallsworth and Vlaev2010; The Behavioural Insights Team, 2014). These frameworks represent memorable mnemonics in which each letter refers to a behavioural science insight that nudgers can (and do) readily apply in their respective contexts. For example, the M in MINDSPACE refers to the importance of the messenger, and the E in EAST reminds nudgers to make the wanted behaviour as easy as possible to engage in.Footnote 2

The present contribution aims to make it easier for nudge practitioners to think about the ethics of nudging. We believe that there is a need for an easy-to-use, actionable ethics framework that summarizes the main points from the debate on the ethics of nudging. We aim to cater to this need by providing a ‘MINDSPACE for ethics’. More precisely, we suggest that policy-makers who want to nudge for good should consider seven core ethical dimensions when designing and implementing behavioural policies: Fairness, Openness, Respect, Goals, Opinions, Options and Delegation. In short, they should nudge FORGOOD.

We hope that the FORGOOD ethics framework can help bridge the gap between the complex, usually abstract and difficult-to-communicate debate on the ethics of nudging and the real-world applications of nudges in the field. In this paper, we do not add arguments to the nudge debate, but rather aim to synthesize existing key dimensions from this debate in a memorable form.Footnote 3 We also do not go into detail in each dimension and/or provide fully worked-out resolutions to ethical issues.Footnote 4 Instead, we highlight and summarize top-level factors in ethical judgements around nudging. The ultimate aim of FORGOOD is to reduce the unintentional misuse of behavioural science in applied policy settings by encouraging voluntary ethical reflection in a systematic way. As such, FORGOOD is as a nudge for practitioners to apply behavioural science ethically, or a nudge to ‘nudge for good’.

The FORGOOD ethics framework

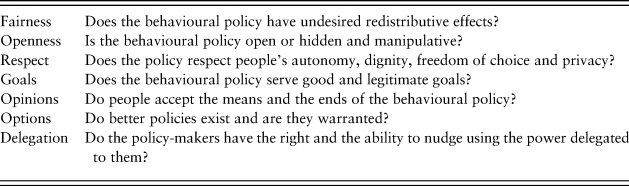

This section presents the details of the FORGOOD ethics framework as summarized in Table 1.Footnote 5 For each of the seven dimensions, Table 1 presents a question that policy-makers can ask themselves in order to identify potential ethical problems. At the end of each of the following subsections, we describe additional questions of the same sort that probe each ethical issue in turn in more detail and summarize the text in the respective subsection. We present these dimensions largely independently of each other and do not consider trade-offs and other links between different dimensions.

Table 1. Summary of the FORGOOD ethics framework for nudging.

Fairness

Ethical nudges aim to help people to make better decisions. However, sometimes nudges affect different people differently and these asymmetric effects often arise from design (Camerer et al., Reference Camerer, Issacharoff, Loewenstein, O'Donoghue and Rabin2003). When decision improvements occur unevenly and when nudges lead to negative externalities for people not subjected to the nudges, concerns about fairness and justice can emerge. In particular, when nudges influence some groups (e.g., with regards to gender, race, age and other relevant dimensions) systematically more than others, fairness considerations are important. Since people have different resources available to them and often hold different preferences, a given nudge might benefit some but fail to benefit others.

For example, requiring people to make active decisions about financial issues might be problematic for people whose minds are already busy because they are struggling to make ends meet (Mullainathan & Shafir, Reference Mullainathan and Shafir2013). Active choosing requirements might thus improve the decisions of people with sufficient behavioural bandwidth, but worsen the decisions made by people who are in states of low mental bandwidth. In such cases, nudges such as simplification and default rules that reduce the need for active decision-making might be the fairer option. Moreover, when selecting the behaviour to modify, differences in the resources available to people should be considered. From a fairness perspective, a nudge that helps underprivileged segments of the population to avoid unnecessary fees might be given priority over a nudge that helps affluent individuals invest more effectively.

Nudges that direct behaviour in a certain way (such as default rules) might lead to fairness concerns when preferences and/or the optimal behaviours differ across individuals. It is fair to assume, for example, that some people prefer to save a lot for retirement and others prefer to spend more in the present. For some households, the optimal behaviour is to invest surplus savings in education or health, and other households are better off by putting the savings into retirement funds. Auto-enrolling people into pension funds is in line with the preferences and economic situations of some but not all households. To the extent that the auto-enrolment is sticky and that people do not opt out (maybe because of inertia), the policy might lead some people to behave against their preferences and best interests.

Another fairness issue arises in cases where changing the behaviour of one group leads to negative spill-over effects onto other groups. For example, if nudging some people to increase their use of a particular beneficial service led to this service becoming overloaded, this could impact negatively on pre-existing users. Similarly, nudging across the population could potentially reduce the premium for conscientious and sophisticated users who make optimal use of product features such as teaser rates or various types of shrouded attributes as a form of price discrimination (e.g., Heidhues & Kőszegi, Reference Heidhues and Kőszegi2017).

Nudge practitioners should consider whether the policy changes welfare on balance by measuring the redistributive effects of nudges. These effects can be measured, for example, by identifying pre-nudge and post-nudge dispersions in key variables, by identifying the change in the distribution of key variables and/or by identifying and comparing first-order effects on the targeted behaviours and second-order effects on other, not-targeted behaviours and outcomes. Whether or not redistributive effects of behavioural interventions are undesired will depend on many context variables. The FORGOOD framework does not provide fully worked-out guidance here, but reminds nudge practitioners to consider fairness when designing and implementing behavioural policies.

• Does the behavioural policy focus too much on one group and neglect another group that is in more need of an intervention?

• Does the behavioural policy lead a subset of the population to behave against their preferences and best interests?

• Does the behavioural policy lead to a reallocation of resources?

Openness

Policy-makers should consider the extent to which the behavioural policy is overt or covert. Most traditional economic policies (such as bans, mandates, taxes and information campaigns) are highly visible and can easily be scrutinized and assessed by the public, such as through voting mechanisms. This is a valuable characteristic because transparency prevents manipulation and manipulation is often viewed as ethically problematic. While most of the currently used behavioural policies are transparent (Alemanno & Sibony, Reference Alemanno and Sibony2015; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2018b), nudges, as it is often argued, have the potential to be difficult to observe and thus to be manipulative (Glaeser, Reference Glaeser2006; Rebonato, Reference Rebonato2012; Hansen & Jespersen, Reference Hansen and Jespersen2013; Barton & Grüne-Yanoff, Reference Barton and Grüne-Yanoff2015; Nys & Engelen, Reference Nys and Engelen2017). Even openly communicated policy interventions might be opaque regarding their policy outcomes. Hence, policy-makers concerned with openness should openly communicate the policy and its anticipated effects on individual behaviour and on other relevant outcomes.Footnote 6

A policy's openness can be defined in at least two ways. It is open if it is (1) communicated openly and (2) easily acknowledged by perceptive consumers (Bovens, Reference Bovens2009). Regarding the first definition, policy-makers might be very open about a policy and announce it publicly in official statements and press briefings. Public announcements about the policy and its goal, rationale and methodology provide an opportunity for the public to scrutinize and criticize the policy. Transparency ensures that policy-makers do not introduce policies that they are not willing to defend publicly. Thaler and Sunstein (Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008) expand on this point referring to Rawls' (Reference Rawls2009) publicity principle. They argue that full disclosure of the behavioural policy and willingness to defend its ‘goodness’ is necessary to make it ethically sound (Sunstein & Thaler, Reference Sunstein and Thaler2003).

The second definition of openness suggests that informing parts of the population of the policy is not yet enough. Additionally, individuals whose behaviours are influenced should be aware of the policy and satisfied with it.Footnote 7 Hence, another definition of openness is that it should be possible, in principle, for everyone who is watchful to identify the influence of the policy on behaviour. Bovens (Reference Bovens2009) calls this ‘token transparency’. In order to achieve token transparency, policy-makers need to have some knowledge about why a given nudge works. However, currently, this type of mechanistic knowledge is not always present, as many applied nudgers are satisfied with identifying ‘what works’ rather than ‘why it works’ (Grüne-Yanoff, Reference Grüne-Yanoff2015; Noggle, Reference Noggle2018). As a first test to identify whether a nudge is token transparent or not, practitioners can differentiate between nudges that target primarily automatic and subconscious decision-making (sometimes called ‘Type 1’ nudges) from nudges that work because they make deliberation easier and more likely (‘Type 2’ nudges). The latter are almost by definition open. More thought about openness needs to be spent on Type 1 nudges (Felsen et al., Reference Felsen, Castelo and Reiner2013; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2016a).

• Does the behavioural policy have the potential to be manipulative?

• Does the public have the chance to scrutinize the behavioural policy?

• Is it possible for the person under the influence of the behavioural policy to identify the policy and its influence and impact?

Respect

To be ethically acceptable, behavioural policies need to respect people and in particular their autonomy, their dignity, their freedom of choice and their privacy. Again, it can be argued that these issues of respect are more relevant when considering Type 1 nudges (that tend to work via the automatic decision-making System 1) than when considering Type 2 nudges (that appeal to deliberative thought and cognitive deliberation in System 2) (Kahneman, Reference Kahneman2011; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2018b). Type 2 nudges can be educational (e.g., disclosure requirements and warnings), reduce the effects of the choice architecture and increase deliberation and autonomous decision-making and are thus inherently respectful.

Respecting autonomy means that nudges do not treat adults as if they were children whose capacities for making good decisions are not being taken seriously. When nudges make people feel as if they were not treated like an independent human being capable of making sensible decisions, these nudges can come across as insults and as being disrespectful (Bovens, Reference Bovens2009, Reference Bovens2013; Hausman & Welch, Reference Hausman and Welch2010; Blumenthal-Barby & Burroughs, Reference Blumenthal-Barby and Burroughs2012; Rebonato, Reference Rebonato2012; Saghai, Reference Saghai2013; White, Reference White2013; Nys & Engelen, Reference Nys and Engelen2017). Nudges that respect autonomy make sure that people's capacities to deliberate and to determine what to choose (their agency) and their sense of self and self-chosen goals (their self-constitution) are not negatively affected (Vugts et al., Reference Vugts, Hoven, Vet and Verweij2018). In particular, when nudges have an influence on preference formation, which is likely when people do not have strong antecedent preferences (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2019), policy-makers should reflect on whether people's agency and self-constitution are respected. Preference learning can happen cognitively, but it often happens via associative learning without people being aware of this. Unconscious preference learning might prevent people from making conscious and autonomous decisions about which preferences they want to learn (Binder & Lades, Reference Binder and Lades2015). Policy-makers should also consider whether nudges might teach people to rely on the government (or other choice architects) making decisions for them and to what extent this is problematic or not (Binder, Reference Binder2014).

Respecting dignity means that nudges do not stigmatize those being confronted with the nudge, as would be the case when pictures of obese people are presented on the packaging of unhealthy food products. Respecting dignity also means that policy-makers acknowledge that behavioural insights do not suggest that people are stupid. To the contrary, even the most intelligent individuals make bad decisions from time to time. To respect people's dignity, policy-makers must not fail to respect people's capacity for rationality and agency and should take seriously the individual's capacity for thought (Bovens, Reference Bovens2009; Hausman & Welch, Reference Hausman and Welch2010; Grüne-Yanoff, Reference Grüne-Yanoff2012; Waldron, Reference Waldron2014; Noggle, Reference Noggle2018). Policy-makers should acknowledge that under certain circumstances everybody, including intelligent and thoughtful individuals, can benefit from nudges, as the world we live in today is hard to navigate. Especially when contemplating the use of Type 1 nudges that encourage automatic, unreflective decision-making policy-makers should consider whether they respect people's dignity (Bovens, Reference Bovens2009; Blumenthal-Barby & Burroughs, Reference Blumenthal-Barby and Burroughs2012; Saghai, Reference Saghai2013).

Respect for freedom of choice is core to the definition of nudges, and nudged individuals are always able to go their own way (Thaler & Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008). Harder policies that go beyond changing the choice architecture and improving navigability (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2019) are not nudges. This is an important distinction, as legal and public scrutiny is more comprehensive for harder policies (Alemanno & Sibony, Reference Alemanno and Sibony2015). However, some nudges are easier to resist than others (Saghai, Reference Saghai2013; Bubb & Pildes, Reference Bubb and Pildes2014). For example, nudges that interfere with people's decisions without them being aware of this interference (often Type 1 nudges) can be difficult to resist. Even when these nudges are open and transparent, individuals who are busy might not perceive the influence of the nudges, which makes them difficult to resist (see also Hausman & Welch, Reference Hausman and Welch2010; Blumenthal-Barby & Burroughs, Reference Blumenthal-Barby and Burroughs2012; Saghai, Reference Saghai2013; Grüne-Yanoff, Reference Grüne-Yanoff2015). For example, default settings that determine what happens if individuals do nothing might lead to busy and boundedly rational individuals believing that they do not have a choice. These individuals’ freedom of choice is reduced to the extent that they are not aware of the choice opportunity. Even if freedom of choice is present in theory, it may not be straightforward to obtain in practice. Moreover, freedom of choice entails that nudges respect the individual right to make errors. If people sometimes err and make decisions that are harmful to themselves, some argue that even in the presence of these ‘internalities’ people should be allowed to make any decision as long as they are not harming others, thereby creating externalities (Sugden, Reference Sugden2008, Reference Sugden2017). When evaluating the ethical acceptability of nudges, policy-makers should consider whether resisting the influence of the nudge is truly easy for the target population and whether effective freedom of choice should be maintained even in the face of self-harming behaviours.

Finally, nudgers need to consider respect for people's right for privacy and control over the use of their personal data. Policies that respect privacy give people the opportunity to give or withhold their consent for different uses of their data. Protocols for data protection can help to respect privacy (Mittelstadt & Floridi, Reference Mittelstadt and Floridi2016) in order to avoid unethical uses of data for targeted or personal pricing and nudging (Bar-Gill, Reference Bar-Gill2019). Given the potential for many nudges to be delivered on digital platforms using large-scale electronic databases, respect for data privacy is clearly a major issue to think through when assessing the ethics of nudges in the future. Those involved in the development, delivery and evaluation of nudge interventions need to have the competency to manage the data ethically.

• Does the behavioural policy respect people's autonomy?

• Does the behavioural policy respect people's dignity?

• Does the behavioural policy respect people's freedom to choose?

• Does the behavioural policy respect people's privacy?

Goals

An important characteristic of behavioural policies from an ethical point of view is whether they serve good goals (Clavien, Reference Clavien2018). The goals of nudges that are in the spirit of libertarian paternalism are to make people's lives ‘better off, as judged by themselves’ (Thaler & Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2018a; Oliver, Reference Oliver2019). Under this ‘better off, as judged by themselves’ criterion, nudges change people's behaviour in a way that these people approve of and are thus ethically legitimate. As argued by a number of commentators, however, policy-makers do not always have an accurate idea about what people approve of. Obtaining such information can be difficult (or even impossible) for outside observers (Sugden, Reference Sugden2008, Reference Sugden2017; Bovens, Reference Bovens2009; Hausman & Welch, Reference Hausman and Welch2010; Grüne-Yanoff, Reference Grüne-Yanoff2012; Rebonato, Reference Rebonato2012; White, Reference White2013).Footnote 8 For example, when people's short-term and long-term preferences differ and when people do not have strong preferences before being nudged, it is extremely difficult to identify what makes people's lives better off, as judged by themselves (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2019). An awareness of these difficulties and of the fact that nudgers might lack information and make miscalculations themselves when aiming to identify what makes people's lives better off can help nudgers to design policies more carefully and ethically. In ‘hard cases’ where it is difficult to use the ‘as judged by themselves’ criterion, some argue that policy-makers should resort to external welfare standards that do not necessarily rely on what the nudged individuals consider best (Read, Reference Read2006; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2019). At the minimum, it is important to explicitly consider whether libertarian paternalistic interventions make people better off and how this ‘better off’ is defined.

Other behavioural public policies are not in the spirit of libertarian paternalism, but nevertheless aim to achieve ethically acceptable goals. These interventions do not aim to paternalistically make nudgees better off, as judged by themselves, but rather they are designed to reduce externalities (e.g., to bring about pro-environmental behaviours), to benefit common goods (e.g., to increase donations to charities) or to benefit other important societal values (e.g., by promoting equality) (Schubert, Reference Schubert2017). While the goals of these behavioural interventions are often ethically legitimate, the means of achieving these goals (in terms of the other dimensions of the FORGOOD framework) still need to be assessed for ethical issues.

There are also behavioural interventions that aim to achieve goals that are not ethically acceptable; for example, because they aim to maximize the nudgers’ profits at the expense of those being nudged. Akerlof and Shiller (Reference Akerlof and Shiller2015) refer to the latter as manipulation and deception, and Thaler and Sunstein call it ‘sludging’ (Thaler, Reference Thaler2018; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2020). In order to differentiate nudging from sludging, nudge practitioners need to have a good idea about what their true goals are, and they have to establish that these goals improve, rather than reduce, welfare. Sometimes, it is obvious whether or not a nudger aims to improve people’s lives. However, at other times, differentiating nudging from sludging and taking into account all of the effects of the nudge can be difficult. Policy-makers should engage in honest cost–benefit analyses considering the effects on the welfare of all actors potentially influenced by the behavioural intervention.

• Does the behavioural intervention serve goals that are ethically acceptable?

• For behavioural interventions that aim to improve people's lives, do these interventions really make people better off and how is this ‘better off’ defined?

Opinions

Different people have different opinions about the ethical acceptability of nudges. Hence, it might not be possible to design a nudge that everybody accepts as permissible. Nudgers should consider how much disagreement is bearable and measure the extent of agreement/disagreement. For example, what value should be given to the views of dissenting minorities? While there are no straightforward answers to questions like this, it can help to consider data on the public acceptability of nudges. Public acceptability of nudges can be concerned with both the ends (what is the goal of the nudge?) and the means (what methods does the nudge use?) of the policy (Clavien, Reference Clavien2018). A strong justification for the nudge is present when nudgers and a large majority of the nudgees agree about both the ends and the means of the policy. While it is not straightforward to identify individual preferences over the ends and means of behavioural policies, policy-makers can get a first idea by asking themselves whether the nudge would withstand public scrutiny.

A more systematic way to identify public opinions about nudges is to rely on surveys that ask people directly whether they would accept certain nudges to be implemented. Previous results from such surveys suggest that there is generally majority support for nudging, but they also show that public opinions differ across different types of nudges (Hagman et al., Reference Hagman, Andersson, Västfjäll and Tinghög2015; Tannenbaum et al., Reference Tannenbaum, Fox and Rogers2017; Sunstein & Reisch, Reference Sunstein and Reisch2019).Footnote 9 The acceptability differs, for example, depending on the means the nudge uses and the ends the nudge aims to achieve. The ends of the intervention seem to be more important than the means for public acceptability (Tannenbaum et al., Reference Tannenbaum, Fox and Rogers2017). Nudges that activate cognitive decision-making processes (Type 2 nudges) receive more favourable ratings than nudges that reduce the need for active decision-making (Type 1 nudges) (Felsen et al., Reference Felsen, Castelo and Reiner2013; Hagman et al., Reference Hagman, Andersson, Västfjäll and Tinghög2015; Jung & Mellers, Reference Jung and Mellers2016; Sunstein et al., Reference Sunstein, Reisch and Rauber2018). Covert nudges are less acceptable than overt nudges (Felsen et al., Reference Felsen, Castelo and Reiner2013), and defaulting people into certain choice options is not always accepted by the majority. However, the literature on public acceptability is still in its infancy, and future studies will inform us as to which nudges are accepted by which segments of the population under which circumstances.

• Considering opinion polls, what is the public opinion about the behavioural intervention?

• How does the public view the goals of the behavioural intervention?

• How does the public view the means used by the behavioural intervention?

Options

It is important to acknowledge that nudges are one of several policy options (Loewenstein & Chater, Reference Loewenstein and Chater2017). At times, policy-makers might be best advised to rely on hard interventions, such as bans, mandates or incentives, in order to change behaviour effectively (Conly, Reference Conly2012). These harder interventions can also be motivated by behavioural insights (Oliver, Reference Oliver2013). It might also be the case that long-term educational interventions or information campaigns are more suitable to achieve the wanted behavioural change. Interventions may also improve individual skills and knowledge, the available set of decision tools or the environment in which decisions are made. These approaches are sometimes called ‘boosting’ (Grüne-Yanoff & Hertwig, Reference Grüne-Yanoff and Hertwig2016; Hertwig, Reference Hertwig2017). Doing nothing and letting markets and spontaneous orders define the choice architecture is often an option worth considering. An ethical argument can be made against nudging if it diverts attention and political will away from better political decisions. For example, if introducing a green nudge diminishes support for a carbon tax (see Hagmann et al., Reference Hagmann, Ho and Loewenstein2019), nudges can be problematic. In many situations, a policy mix is likely to be the best strategy, and nudges can complement other interventions.

One important consideration to establish whether a nudge is an adequate policy and is preferable to other policy options is cost–effectiveness. Policy-makers have only recently begun to nudge, and the evidence regarding the effectiveness of nudging is not yet strong. Some researchers argue that nudges are very cost–effective (Benartzi et al., Reference Benartzi, Beshears, Milkman, Sunstein, Thaler, Shankar and Galing2017), but others warn that the effectiveness of behavioural policies might well be limited in comparison to harder policies (Loewenstein & Chater, Reference Loewenstein and Chater2017). For example, nudging alone will likely not solve some of the most pressing problems, including climate change, unemployment and low mental health. Thaler and Sunstein (Reference Thaler and Sunstein2008, p. 200) state that ‘the most important step in dealing with environmental problems is getting the prices right.’ In order to measure the effectiveness of nudges, it is important to test whether the nudge works in the relevant context (Deaton & Cartwright, Reference Deaton and Cartwright2018). Moreover, it is important to consider the possibility of unwanted side effects when comparing nudges with other policies. Through considering these various effects, a cost–benefit analysis can indicate whether the nudge is more cost–effective than alternative policies.

• Are there other policy options?

• Is the behavioural intervention the best policy amongst all of the policy options?

• Does the behavioural policy divert attention and/or political will away from better political decisions?

• Is the behavioural policy more or less cost–effective than other policies?

Delegation

Much of the framework so far has focused on the ethics of nudges themselves. However, it is crucial also to consider the ethical aspects of the relationship between nudgers and nudgees. The power to nudge does not come from nowhere (Alemanno & Spina, Reference Alemanno and Spina2014; Clavien, Reference Clavien2018). Instead, it is delegated to the policy-makers. Hence, those employing nudge techniques need to ask themselves whether the delegation of the power to nudge to themselves was legitimate and resulted from a fair and legal process. Moreover, behavioural policy-makers need to reflect on whether they themselves are competent enough to apply the behavioural scientific insights effectively and ethically (Clavien, Reference Clavien2018).

When reflecting on how the power to nudge was delegated to them, behavioural policy-makers should consider whether they might have conflicts of interests. Nudgers should consider why they are in a position to influence other people's behaviour. Was this power delegated to them via the law, by professional function or by a dialogue between public administrations and representatives of the private sector? Or are they in this position of power due to the influence of groups with strong interests? Potential conflicts of interest may interact with other aspects of the FORGOOD framework. For example, conflicts of interest might influence public acceptability and constrain the set of other policy options that the policy-makers can choose from. But considering conflicts of interest is also important intrinsically in terms of evaluating optimal relationships between citizens, large organizations and governments. To show that they have reflected on potential conflicts of interests, policy-makers can make an effort to communicate why they are legitimated to influence people's behaviours (Clavien, Reference Clavien2018). How these issues are communicated may also impact upon both public trust in the nudges themselves and also upon the institution engaged in nudging (Clavien, Reference Clavien2018).

When reflecting on their competency as choice architects, policy-makers should consider whether they are competent enough to complete the delegated tasks efficiently. Policy-makers are humans too, and hence potentially subject to the cognitive biases identified by behavioural economics (e.g., Rebonato, Reference Rebonato2014). For example, bounded willpower can lead policy-makers to be tempted to make policies that are beneficial in the short term, but problematic in the long term (Rizzo & Whitman, Reference Rizzo and Whitman2009). The extent to which harm may result from inattention to organizational biases is something to consider as part of the ethical evaluation of nudges as well. Similarly, the design and evaluation of different types of nudging initiatives may require expertise outside the capacity of the institution, and it merits discussion as to how risks in this regard are dealt with. Moreover, it is essential to critically reflect on the scientific base on which the behavioural intervention is built. The replication crisis in the behavioural sciences and other fields suggests that some of the behavioural insights we believed to be true might not be real or might be weaker than assumed.

A focus on the ethical aspects regarding delegation encourages nudging organizations to review their own competence and trustworthiness in conducting nudge activities. This goes beyond thinking of ethical aspects of individual nudges on a case-by-case basis and includes an element of self-reflection. This self-reflection is also helpful when using the FORGOOD framework to identify potential ethical problems. When going through the seven elements of the framework, policy-makers should reflect on whether they consider each element without bias and in sufficient detail.

• Does the policy-maker have conflicts of interest?

• Does the policy-maker have the competency to design, administer and evaluate the behavioural policy?

• How do potential conflicts of interest and lack of competency influence ethical assessment and communication?

Discussion

FORGOOD's purpose

The previous section presented the FORGOOD ethics framework for behavioural policy-making. The framework's main aim is to encourage behavioural policy-makers to think more systematically about the ethics of nudging. FORGOOD offers a memorable and easy way to start this process. We think of the framework as a tool that behavioural policy-makers can use on a voluntary basis throughout the development and application of behavioural policies. Just as MINDSPACE is a mnemonic that helps one to recall various behaviourally informed ways to change behaviour, FORGOOD can help one to think about the ethical issues that may come up when designing behavioural policies. The framework highlights broad principles rather than specific criteria and can thus be applied to a multitude of behavioural interventions. It provides a starting point for a more nuanced and specific case-by-case discussion about the ethical permissibility of a given nudge. One application of the framework, in particular, could be as a stimulus for pre-mortem sessions taking place before the development of behavioural applications in organizations in order to clarify potential ethical issues in advance (Klein, Reference Klein2007).

Ethical standards are evolving and differ across individuals and cultures, and there are many grey areas. The FORGOOD framework does not provide an answer as to whether a certain nudge is ethically permissible or not. Rather, it gives guidelines as to where to look for potentially problematic issues. Similarly, we do not recommend the use of the framework to calculate something like an acceptability index by, for example, weighting and trading-off different considerations. We also do not envisage that FORGOOD will be used as a mandatory ethical checklist and hence do not expect that it will lead to bureaucratic delays in the implementations of public policies. FORGOOD helps policy-makers to evaluate the ethical acceptability of a single nudge. It does not deal with macro-issues relating to the interplay and interactions between multiple nudges at the same time and questions on the societal level as to whether one wants to live in a world where nudges by policy-makers are commonplace. Finally, FORGOOD deals with the ethics of the design of behavioural policies. The framework does not deal with the ethics of the experiments that later on inform behavioural policies. It is not a substitute for ethical approval from research ethics panels. For example, the framework does not deal with informed consent, power dynamics and other aspects that are typically covered by research ethics boards in cases where these are required.

The complexity/uptake trade-off

A potential danger of any ethics framework is that it is too simplistic. It might not include important dimensions and/or it might cover some dimensions with insufficient detail. Another danger is that the ethics framework is not used in practice because it is too complex. Our strategy for FORGOOD was to keep the framework as simple and memorable as possible, but complex enough to capture most of the dimensions in the nudge debate. We chose the terms in FORGOOD in the hope that they are easy for policy-makers to make intuitive sense of. We hope that FORGOOD is easily understandable, attractive for policy-makers to use, will be used by many social groups and comes at the right time. There are ethical considerations that are relevant for any type of policy influence – not just nudging – that FORGOOD does not deal with. More complex frameworks would be able to capture more ethical aspects, but they would come at the cost of greater complexity, which would also make the framework less memorable and less likely to be adopted on a voluntary basis by choice architects.

Alternatives from the literature

We are not the first to highlight the need for an actionable guide that helps behavioural policy-makers to think about the ethics of nudging. For example, Sunstein and Reisch (Reference Sunstein and Reisch2019) present a Bill of Rights for Nudging in which they argue that: (1) public officials must promote legitimate ends; (2) nudges must respect individual rights; (3) nudges must be consistent with people's values and interests; (4) nudges must not manipulate people; (5) nudges should not take things from people, and give them to others, without their explicit consent; and (6) nudges should be transparent rather than hidden. Additionally, they argue that policy-makers should consider the welfare and autonomy implications of nudges. In earlier work, Sunstein focuses on welfare, autonomy and dignity as the three key dimensions, and he discusses manipulation and biased officials as additional important aspects (e.g., Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2015). Thaler (Reference Thaler2015) presents a more pragmatic approach and argues that three principles should guide the use of nudges: (1) all nudging should be transparent and never misleading; (2) it should be as easy as possible to opt out of the nudge; and (3) there should be good reason to believe that the behaviour being encouraged will improve the welfare of those being nudged.

Ethical frameworks by other researchers include the suggestion by Clavien (Reference Clavien2018) to evaluate the acceptability of a nudge by asking four sets of questions, referring to: (1) the goals of the behavioural policy; (2) the policy's evidence base as an indication of effectiveness; (3) an awareness of limitations, conflicts of interests and issues of trustworthiness; and (4) consideration of ethics more generally. Jachimowicz et al. (Reference Jachimowicz, Matz and Polonski2017) suggest using an ethics checklist that covers six core principles: (1) aligned interests; (2) transparent processes; (3) rigorous evaluation; (4) data privacy; (5) ease of opting out; and (6) cost–benefit analysis. Fabbri and Faure (Reference Fabbri and Faure2018) suggest that ethical guiding principles should be developed first by citizens, and only then should policy-makers agree on these principles before implementing behavioural policies. Moreover, they suggest installing an independent agency that oversees behavioural policy-making based on a document that provides precise and strict guiding principles and procedures. Finally, the BASIC toolkit published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) presents a detailed list of 45 ethical guidelines that policy-makers should consider when conducting a behavioural science project (Hansen, Reference Hansen2019).

Compared to these frameworks, FORGOOD is likely to be more memorable and easier for policy-makers to recall and apply. Thus, the chances that the framework is actually used in practice are higher. At the same time, FORGOOD does capture most of the considerations described in the alternative frameworks. Accordingly, we believe that FORGOOD provides a significant addition to this literature, with great potential to actually be used in applied settings.

Conclusion

The FORGOOD ethics framework summarizes seven key ethical dimensions that the literature on the ethics of nudging has identified. It suggests that policy-makers should consider Fairness, Openness, Respect, Goals, Opinions, Options and Delegation when designing behavioural policies such as nudges. Considering these dimensions helps behavioural policy-makers to think systematically about the ethics of nudging and thus to identify potential ethical problems before they arise. We believe that FORGOOD can and should be used on a voluntary basis by various groups and in various contexts. It can be used to support teaching ethical behavioural policy-making; it can be used in business and industry settings to reduce the chances of unwanted unethical behaviour that might end up being covered unfavourably in the media; and it can be used by policy-makers to think about the ethics of the behavioural policies they intend to implement.

We expect that FORGOOD will evolve over time and encourage behavioural researchers and behavioural policy-makers to use it as a starting point to develop their own voluntary, case-specific ethics frameworks.Footnote 10 Further developments of the literature might require changes to the framework, and we welcome comments, adaptations and improvements on the framework. In the future, the ethics framework might develop into a set of injunctions from which policy-makers could find actionable guidance. It might also be the basis for behavioural science ethics certifications, behavioural terms and conditions or a legal framework that defines when nudges are illicit. For now, however, we view FORGOOD itself as not more or less than a nudge to ‘nudge for good’.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank students and seminar participants at UCD, Trinity College Dublin, Maynooth University, Stirling University, LSE, BXArabia2019, the two anonymous reviewers and in particular Christine Clavien, Muireann Quigley and Constantin Gurdgiev for many helpful comments.

Financial support

Leonhard Lades has been supported by a grant from the Irish Environmental Protection Agency (project name: Enabling Transition, 2017-CCRP-FS.32).