Introduction

Ageing is associated with significant life changes, such as retirement, role changes or an increase in the likelihood of chronic illness (United Nations, 2011). Therefore, changes in the content of worry and anxiety are frequent in old age, with increases in those related to health and disability (Fergus et al., Reference Fergus, Griggs, Cunningham and Kelley2017). Salkovskis and Warwick (Reference Salkovskis, Warwick, Asmundson, Taylor and Cox2001) proposed that concerns associated with over-estimating the likelihood and cost of health problems are common in the older population. In addition, the difficult economic situation that Spain has experienced in recent years (Serrano et al., Reference Serrano, Latorre and Gatz2014) may have aggravated economic concerns about the cost of health problems in the older Spanish population. One of the main health-related worries for older adults is becoming dependent and, consequently, being a burden to others (e.g. Gudat et al., Reference Gudat, Ohnsorge, Streeck and Rehmann-Sutter2019; Jahn and Curkrowicz, Reference Jahn and Cukrowicz2011). The results obtained by Jahn et al. (Reference Jahn, Van Orden and Cukrowicz2013) suggest that the perceptions of burden on relatives are harmful to older adults in the community, especially when reporting feeling like a burden on a spouse. Therefore, independence/autonomy is a core issue in old age, and the associated desire of not being a burden to others is a common worry for older people (Bryant et al., Reference Bryant, Corbett and Kutner2001). Even though self-perception of being a burden seems to be a relevant variable for older adults, it has been scarcely studied in this population.

As far as we know, the studies that have explored the perception of being a burden in the elderly population have been conducted with samples composed of physically unhealthy older adults. For example, Mead et al. (Reference Mead, O’Keeffe, Jack, Maèstri-Banks, Playfer and Lye1995) explored different motives for not choosing cardiopulmonary resuscitation in patients with cancer in two different age groups: younger patients (under 70 years; mean 53 years, SD = 12) and older patients (70 years and older; mean 80 years, SD = 7). They found that the most frequent motive in the older patients’ group was feelings of self-perception of being a burden on their family, suggesting that self-perception of being a burden may be particularly frequent among older adults.

In the general population, the concept of self-perception of being a burden has also been explored mainly in the context of patients with serious illness, principally terminal cancer (Cousineau et al., Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003; McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Wilson, Lobchuk and Brajtman2007; Mead et al., Reference Mead, O’Keeffe, Jack, Maèstri-Banks, Playfer and Lye1995). For example, McPherson et al. (Reference McPherson, Wilson, Lobchuk and Brajtman2007) reported the existence of physical, social and emotional concerns associated with the construct of self-perception of being a burden in these patients. Participants’ concerns included depending on others for physical care needs, concerns about the emotional impact of their illness and death, and concerns about not being able to satisfy important functions and obligations. Interestingly, these concerns were expressed not only with respect to the current situation of the participants, but also in anticipation of a future decline in health. Therefore, self-perceptions of being a burden can occur as a result of a relational-social process that emphasises empathic concern about the difficult situation of others who must face the challenges caused by a terminal illness (McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Wilson, Lobchuk and Brajtman2007).

In their study with patients undergoing hemodialysis, Cousineau et al. (Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003) suggested that the construct of ‘feelings of being a burden’ is a multifaceted phenomenon, which includes the feeling of guilt for being responsible for the caregiver’s difficulties. Previous studies have also found self-perception of being a burden to others to be associated with feelings of guilt (Grant et al., Reference Grant, Murray, Grant and Brown2003; Gudat et al., Reference Gudat, Ohnsorge, Streeck and Rehmann-Sutter2019; McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Wilson, Lobchuk and Brajtman2007). Guilt feelings arise from the perception of moral transgression, with the painful effect that appears from the belief of hurting another (O’Connor et al., Reference O’Connor, Berry, Weiss, Bush and Sampson1997), which implies self-reproach, and this frequently generates maladaptive consequences such as remorse (Klass, Reference Klass1987) for one’s actions or lack of action (Tilghman-Osborne et al., Reference Tilghman-Osborne, Cole and Felton2010).

One limitation of previous studies aimed at exploring the concept of self-perceptions of being a burden is that they have been mainly focused on patients with serious physical illness (Cousineau et al., Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003; McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Wilson, Lobchuk and Brajtman2007; Mead et al., Reference Mead, O’Keeffe, Jack, Maèstri-Banks, Playfer and Lye1995). However, this concept has rarely been analysed in patients with mental illness, despite the evidence finding that self-perception of being a burden is a relevant concern in the development of some forms of psychopathology, such as suicidal behaviour (Joiner, Reference Joiner2005; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte and Joiner2012), thus highlighting the relevance that self-perception of being a burden can have on those who suffer from it. Suicide is a relevant issue in the older adult population, as the suicide rate is higher among this population than in younger age groups (World Health Organization, 2017). For example, in Spain, 1402 people aged 60 and over committed suicide in 2018; that is, more than three people over the age of 60 committed suicide every day in Spain in 2018 (National Statistics Institute, 2018).

Furthermore, feelings of guilt associated with self-perceptions of being a burden have not been explored in healthy older adults, even though they may be present. While it is true that frailty and dependence are associated with old age, it is not a necessary condition in older adults (Kamat et al., Reference Kamat, Martin, Jeste, Chiu, Shulman and Ames2017). However, some older people may perceive themselves as having worse physical functioning or mental health than they actually do as a consequence of the influence of ageing stereotypes. Ageing stereotypes have been defined as beliefs that contain disparaging convictions about old people as a category (Levy and Langer, Reference Levy and Langer1994). Levy (Reference Levy2003) suggests that these negative stereotypes about old age are internalised from childhood to adulthood, and become self-stereotypes when individuals begin to perceive themselves as older adults. Negative self-perceptions of ageing seem to be associated with the perception of worse functional health (Levy, Reference Levy2003) and may be linked to feelings of being a burden. For example, some healthy older adults could start needing some occasional help (e.g. to move something heavy, to climb a ladder, to learn how to use a new smartphone). Such occasional help may activate the ageing stereotypes and generate guilt due to the perception of needs or anticipations of future needs that others must solve. Therefore, this anticipation of threat, originating from the internalisation of ageing stereotypes, may lead to the emergence of self-perceptions of being a burden and guilt feelings associated with these self-perceptions.

Even though the construct of guilt has been previously linked in the scientific literature to distress (e.g. depressive and anxious symptomatology; Gallego-Alberto et al., Reference Gallego-Alberto, Losada, Vara, Olazarán, Muñiz and Pillemer2018; Li et al., Reference Li, Tendeiro and Stroebe2018; McIvor et al., Reference McIvor, Degnan, Pugh, Bettney, Emsley and Berry2019), to our knowledge, no study has yet analysed the association between feelings of guilt for perceiving oneself as a burden and distress in older adults. In addition, even though scales for measuring self-perception of being a burden do exist (e.g. Self-Perceived Burden Scale; Cousineau et al., Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003), there is no available measure specifically focused on the assessment of guilt feelings related to perceiving oneself as a burden to others.

Taking into account the above-mentioned issues, the main objective of this study is to adapt the Self-Perceived Burden Scale developed by Cousineau et al. (Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003) to the evaluation of the feelings of guilt for perceiving oneself as a burden for the family in older adults without explicit functional or cognitive impairment; and to analyse its psychometric properties. The original scale, proposed by Cousineau et al. (Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003), measures feelings of being a burden to their caregivers in out-patients undergoing hemodialysis. The Spanish version of the scale, validated by Arechabala et al. (Reference Arechabala, Cantoni, Barrios and Palma2012), showed a unidimensional structure. The final objective of this study is to analyse the degree to which guilt feelings related to self-perception as a burden to the family are associated with psychological distress (depressive and anxious symptoms) in healthy older adults.

We hypothesise that: (1) the Guilt associated with Self Perception as a Burden Scale (G-SPBS) will show adequate psychometric properties, (2) G-SPBS will show a unidimensional structure, (3) the G-SPBS will be positively and significantly associated with self-perception burden, and (4) G-SPBS will be associated positively and significantly with depressive and anxious symptomatology.

Method

Participants

Participants were 298 older adults from the city of Madrid (Spain) who agreed to participate in the study. The sample had a mean age of 72.4 years (SD = 5.9) and consisted primarily of women (72.1%). The inclusion criteria to participate in the study were being 60 years old or older, and not showing explicit cognitive or functional decline. Participants are autonomous people who live in the community and do not use care services for the elderly (such as residences or day centres). Participants were recruited through associations for the elderly and social centres offering activities and courses for older adults.

Procedure

Several associations for the elderly, and cultural and social centres were contacted in order to ask for their collaboration in the sample recruitment for the study, which was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (reference number: 2602201804518). The collaborating centres provided the contact information of participants, who were requested to read and sign the informed consent. Finally, participants completed the assessment protocol with the supervision of trained psychologists, who answered the participants’ doubts or questions.

Variables and instruments

In addition to socio-demographic variables (age and gender), the following variables were assessed.

Guilt associated with self-perception as a burden

The feelings of guilt associated with self-perception as a burden to the family were measured through the adaptation of items from the Self-Perception Burden Scale (SPBS; Cousineau et al., Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003). The aim was to have a shorter measure that could be easily used in clinical settings and research. Therefore, only those items were selected which showed an item-test correlation greater than .50 in the Spanish validation of the scale (Arechabala et al., Reference Arechabala, Cantoni, Barrios and Palma2012) in a sample with similar cultural characteristics (both Hispanic samples). An exception was made for the item ‘I feel that I am a burden to my family’, which was kept in the assessment protocol as an indicator of the self-perceived burden (see next paragraph). The content of the selected items was adapted to assess the extent of guilt linked to feelings of self-perception of burden on the family, instead of on the caregiver (e.g. the item ‘I worry that my caregiver is over-extending him/herself in helping me’ was adapted into ‘I feel guilty for overburdening my family to care for me’). Sixteen of the 25 original items were finally included in the scale. All the items were answered on a 5-point Likert scale, from 1 (‘never or almost never’) to 5 (‘almost always’). The psychometric properties of this scale, including factor analysis and Cronbach’s alpha, are described in the Results section.

Self-perceived burden on the family

Self-perceived burden was measured through a single item. The item ‘I feel that I am a burden to my caregiver’ of the scale proposed by Cousineau et al. (Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003) was adapted for the measurement of self-perceived burden on the family: ‘I feel that I am a burden to my family’.

Depressive symptomatology

Depressive symptomatology was assessed through the Spanish version (Losada et al., Reference Losada, de los Ángeles Villareal, Nuevo, Márquez-González, Salazar, Romero-Moreno and Fernández-Fernández2012) of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D; Radloff, Reference Radloff1977). This scale is composed of 20 items (e.g. ‘I felt sad’) which measure the level to which the subject manifested different depressive symptoms during the previous week. Response options consisted of a 4-point Likert scale with a range from 0 (‘rarely or none of the time’) to 3 (‘most or all of the time’). The internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) of the scale in the present study was .86.

Anxious symptomatology

The Spanish version (Márquez-González et al., Reference Márquez-González, Losada, Fernández-Fernández and Pachana2012) of the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI; Pachana et al., Reference Pachana, Byrne, Siddle, Koloski, Harley and Arnold2007) was used for measuring anxious symptomatology. The scale has 20 items (e.g. ‘I worry a lot of the time’) with a dichotomous response option (0 = ‘no’ and 1 = ‘yes’). The internal consistency index obtained in the present study according to Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was .93.

Data analysis

Sample and item characteristics were analysed through means, standard deviations and ranges of the assessed variables. Item-to-item correlations and Cronbach’s alpha of the item were also analysed.

We explored the dimensionality of the adapted scale with factor analysis. First, we examined Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) and Bartlett’s sphericity tests to determine whether sample data were suitable for factor analysis. In order to retain the underlying number of factors to reproduce the observed correlation matrix, we used multiple criteria. Parallel analysis was calculated using polychoric correlation matrix as input (given the categorical metric of the items) with psych algorithm (Revelle, Reference Revelle2017) and Pearson correlation matrix. Specifically, following the criteria of Longman et al. (Reference Longman, Cota, Holden and Fekken1989), parallel analysis was done using the mean eigenvalues and the 95th percentile eigenvalues. Parallel analysis involves comparing the current eigenvalues with the random data eigenvalues and typically provides an optimal solution for the number of components to be retained (O’Connor, Reference O’Connor2000). A Geomin oblique rotation method was used. To assess model fit to the data, different statistics were used. Chi-square tests (χ2) and standardised root mean square residuals (SRMR) were used as absolute fit indices, comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) as comparative fit indices, while root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) and its 90% confidence interval were used as a model parsimony fit index. Acceptable model fit was established for values of RMSEA ≤ 0.06, 90% CI ≤ 0.08, SRMR ≤ 0.08 and CFI and TLI ≥ 0.95 (Brown, Reference Brown2015; Hu and Bentler, Reference Hu and Bentler1998). Finally, reliability was assessed through internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) and, in order to evaluate the convergent validity of the G-SPBS, Pearson’s correlations between the scale and the variables evaluated in the present study were performed. All analyses were conducted using Mplus 7.0 software (Muthén and Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2012).

Results

Item analysis

Before using factor analysis, individual items were examined with univariate descriptive statistics, item-to-item correlations and with Cronbach’s alpha if the item was deleted. Results are shown in Table 1. After this initial analysis, following Boateng et al. (Reference Boateng, Neilands, Frongillo, Melgar-Quiñonez and Young2018) item number 15 was deleted and not included in further analyses, due to the low general inter-item associations and because it is the only item that increased internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha) when removed. The remaining items showed good inter-item associations.

Table 1. Item-to-item correlations, item descriptive data and Cronbach’s alpha if the item has been deleted

*p < .05; **p < .01.

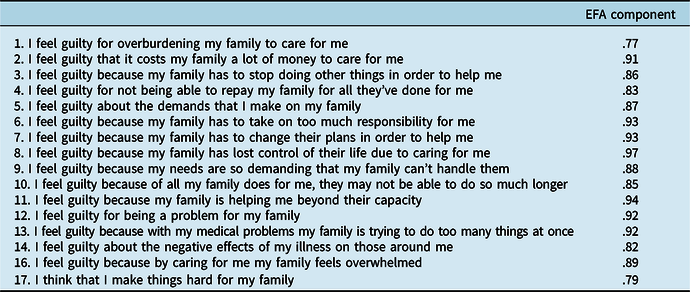

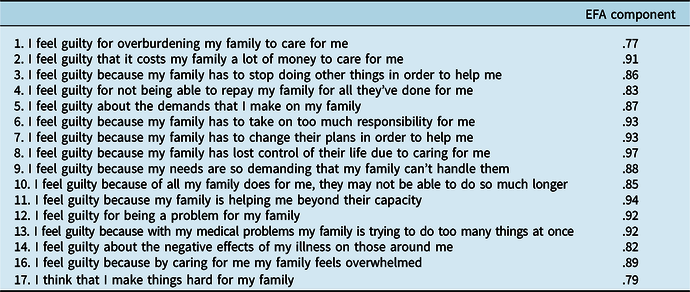

Exploratory factor analysis

The KMO (0.908) and Bartlett’s sphericity test (χ2 = 3062.88, p < .001) showed the data to be highly suited to factor analysis (i.e. strong relationships between items). Subsequently, we analysed the optimal number of factors suggested by parallel analysis. Both parallel analyses using polychoric correlation matrix and Pearson correlation matrix suggested a one-factor solution for the G-SPBS scale. Only the first empirical eigenvalue (= 9.127, calculated from principal component analysis; 57.04% of the total variance of the guilt feeling associated with self-perception as a burden) was larger than the first simulated eigenvalue (and also larger than the 95th percentile simulated eigenvalue). Consequently, one factor was retained. The unidimensional model had an excellent fit to the data: χ2 (104) = 188.54, p < .01; RMSEA = 0.05, CI 90% 0.044–0.064; CFI = 0.99; TLI = 0.99; SRMR = 0.05. All factor loadings were higher than .70 (Table 2), showing that all items were reliable observed indicators of the measured dimension.

Table 2. Factor loadings of the Guilt associated with Self-Perception as Burden Scale items

Reliability

The internal consistency of the G-SPBS, as measured through Cronbach’s alpha, was .94.

Concurrent validity

The correlations between the assessed variables are shown in Table 3. Guilt associated with self-perception as a burden showed significant and positive associations with age, burden, depression and anxiety. No significant association between guilt associated with self-perception as a burden and gender was obtained.

Table 3. Correlation matrix

1 = woman; *p < .05; **p < .01.

Discussion

The main objective of the present study was to adapt the Self-Perceived Burden Scale (Cousineau et al., Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003) to the assessment of G-SPBS in older adults without visible functional or cognitive symptoms, and to analyse its psychometric properties. Our findings suggest that the G-SPBS has a unidimensional structure (hypothesis 2), excellent internal consistency, and explains a significant proportion of variance of the guilt associated with the self-perception as a burden for the family (hypothesis 1). These results suggest that the G-SPBS can be used with older adults without explicit functional or cognitive symptoms. A significant and positive association was found between feelings of guilt for perceiving oneself as a burden and age. These findings are consistent with those obtained by Mead et al. (Reference Mead, O’Keeffe, Jack, Maèstri-Banks, Playfer and Lye1995), who found that older adults (>70 years) with cancer talked about feelings of being a burden more frequently than other age groups (<70 years).

The second objective of the present study was to analyse the relationship of G-SPBS with psychological distress. A significant and positive association was found between feelings of guilt associated with self-perception as a burden and the self-perception of being a burden (hypothesis 3). This finding supports the definition proposed by Cousineau et al. (Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003), who stated that feelings of guilt arise from the perception of being responsible for other relatives’ difficulties associated with an anticipated experience of care; that is, by perceiving oneself as a possible source of burden for the relative.

In addition, positive and significant associations between G-SPBS and depressive and anxious symptomatology (hypothesis 4) were found. These results suggest that a higher level of feelings of guilt for perceiving oneself as a burden could be associated with higher psychological distress in older adults without visible functional or cognitive symptoms. Specifically, in this study higher scores in feelings of guilt for perceiving oneself as a burden were associated with higher scores in depressive and anxious symptoms. The association of guilt feelings with depression and anxiety has been observed previously (e.g. Cândea and Szentagotai-Tăta, Reference Cândea and Szentagotai-Tăta2018; Kim et al., Reference Kim, Thibodeau and Jorgensen2011). Thus, self-perception of being a burden may generate guilt feelings and this guilt feeling may be related to depression and anxiety. However, a limitation of previous studies exploring the concept of self-perception of being a burden is that they have mainly focused on patients with serious physical illness (Cousineau et al., Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003; McPherson et al., Reference McPherson, Wilson, Lobchuk and Brajtman2007; Mead et al., Reference Mead, O’Keeffe, Jack, Maèstri-Banks, Playfer and Lye1995). As mentioned, some individuals with mental health problems also present this self-perception of being a burden (Joiner, Reference Joiner2005; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Witte, Cukrowicz, Braithwaite, Selby and Joiner2010; Van Orden et al., Reference Van Orden, Cukrowicz, Witte and Joiner2012), and this self-perception may, in turn, facilitate guilt feelings that could aggravate the symptoms of mental illnesses such as depression, and then increase the guilt feeling associated with self-perception as a burden; also, having depression could favour or increase feelings of guilt which, in turn, may increase the depressive symptomatology in a mutual feedback interaction. Hence, in the case of mental health problems, this relationship could be cyclic and even more relevant than in the case of physical illness.

An important result of this study is the finding that guilt feelings for perceiving oneself as a potential source of burden for other relatives are present in older adults without evident symptoms of functional or cognitive decline, assessed in a context where they are able to do activities or courses in their field of interest (e.g. literature, painting or software use). In agreement with the theoretical arguments presented by McPherson et al. (Reference McPherson, Wilson, Lobchuk and Brajtman2007), we hypothesise that these feelings can be explained through a relational-social process but, in this case, associated with concerns about how the family will cope with the changes that ageing causes in older people. The concerns about how the family will deal with the changes caused by ageing may be influenced by stereotypes towards ageing, mainly by negative stereotypes about the health of older people (Levy, Reference Levy2003). Laidlaw and McAlpine (Reference Laidlaw and McAlpine2008) suggest that ‘for many older people, diagnosis with a chronic medical condition is equated with disability, even when this is not necessarily the case’ (p. 255). This false belief (or negative ageing stereotypes) can be reinforced by the memories of caring for their own elderly relatives in different historical conditions (Laidlaw and McAlpine, Reference Laidlaw and McAlpine2008). At the same time negative stereotypes related to the mental health of older people (e.g. ‘Most older people often feel unhappy’; Palmore, Reference Palmore1988), may facilitate these guilt feelings of perceiving oneself as a potential source of burden, which may act as a confirmation of these negative stereotypes. Furthermore, as mentioned in the case of individuals with mental health problems, this relationship could be cyclic. The relationship found in this study between guilt feelings associated with self-perception as a burden and depression and anxiety might confirm this hypothesis. However, future studies should further explore this relation in a sample of healthy older adults and older diagnosed with mental health problems.

The results obtained in the present study also suggest that feelings of guilt for perceiving oneself as a burden is a variable with clinical relevance. While the SPBS (Cousineau et al., Reference Cousineau, McDowell, Hotz and Hébert2003) assesses the concerns (cognitions) of people who receive care regarding the effects that their care may have on their caregivers, the G-SPBS assesses feelings of discomfort caused by self-perceived thoughts as a burden, such as feelings of guilt. The self-perception of being a burden can occur without the presence of discomfort. For example, receiving care or perceiving yourself as a burden can be understood as a normal situation during an illness, and some individuals may even think that is a family obligation (e.g. Losada et al., Reference Losada, Márquez-González, Vara-García, Barrera-Caballero, Cabrera, Gallego-Alberto, Olmos and Romero-Moreno2019; Sabogal et al., Reference Sabogal, Marín, Otero-Sabogal, Marín and Perez-Stable1987). Taking this into account, the proposed scale is presented as a measure of discomfort, specifically feelings of guilt, that arise associated with the self-perception of being a burden. The association between guilt and psychological distress suggests that these feelings of guilt are relevant variables to be considered in order to understand, assess and improve well-being of older adults. Satre et al. (Reference Satre, Knight and David2006) point out how important it is ‘to counteract the loss of important social roles and autonomy and to challenge the belief that the client is a burden to caregivers’ (p. 13) in the adaptation of cognitive behavioural intervention strategies for older adults. Likewise, Charlesworth and Greenfield (Reference Charlesworth and Greenfield2004) point out that one of the barriers to working in psychological therapies with older people is stereotypical prejudices like ageism. Similarly, our results suggest that feelings of guilt associated with self-perception of burden should also be explored and managed in psychological interventions with older adults. In this regard, it may be possible that guilt related to self-perception as a burden to others may trigger dysfunctional behaviours such as emotional suppression, non-expression/communication of feelings and needs, or not asking for help when it is needed. Likewise, Nieuwenhuis et al. (Reference Nieuwenhuis, Beach and Schulz2018) found in older adult care recipients an association between concerns about being a burden and a number of unmet needs. Not asking for help may reduce the probability of obtaining improvements in other areas of their lives (Ryninks et al., Reference Ryninks, Wallace and Gregory2019). Consequently, the developed scale is presented as a clinical instrument that could be used in older adults with physical or mental health problems, but also with healthy older adults who could have internalised ageing stereotypes.

The present study has some limitations that highlight the need for additional studies confirming the obtained results. The use of a convenience sample of older adults who participate in associations for the elderly may limit the generalisation of the findings to a representative population of older adults without functional limitations. Also, the cross-sectional nature of the study does not allow causal inferences to be made about, for example, the associations between guilt feelings for perceiving oneself as a burden and the development of anxious or depressive symptoms.

In addition to this, the present study has been carried out with a sample composed of Spanish older adults, and so cultural issues may be influencing the results. Cahill et al. (Reference Cahill, Lewis, Barg and Bogner2009) compared samples of older adults of European descent with African, African American and African Caribbean older adults, all of whom had functional limitations and were receiving care from a family member. Older adults of European descent reported feelings of guilt in relation to burdening families, but the other older adults group made more references to guilt in the context of losing independence and their own ability to contribute to their social networks.

In spite of these limitations, our results suggest that the G-SBPS is a valid and reliable scale for measuring feelings of guilt associated with self-perception as a burden in older adults without functional or cognitive limitations. The G-SPBS can contribute to increasing our understanding of factors that contribute to older adults’ mental health problems, which shows the potential of G-SPBS as a useful measure for research and clinical purposes. As far as we know, this is the first study that assesses feelings of guilt associated with self-perception as a burden in healthy older adults. Feelings of guilt associated with self-perception as a burden constitutes an unexplored variable that seems to be relevant to the explanation of depressive and anxious symptoms in older adults.

Acknowledgements

We thank the City Council of Getafe and the Older Adults Cultural Centers of Ferrer I Guardia and Ramón Rubial (Madrid, Spain) for their support in the recruitment of the sample.

Financial support

Samara Barrera was supported by a FPU grant from the Spanish Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport.

Conflicts of interest

María del Sequeros Pedroso-Chaparro, Andrés Losada, Isabel Cabrera, María Márquez-González, Ricardo Olmos, Rosa Romero-Moreno, Carlos Vara-García, Laura Gallego-Alberto and Samara Barrera-Caballero have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statement

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Universidad Rey Juan Carlos (reference number: 2602201804518).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.