Introduction

Compulsive buying disorder (CBD) is operationally defined as an impulsive control disorder (Robbins and Clark, Reference Robbins and Clark2015) characterised by persistent, excessive and impulsive consumerism (Müller et al., Reference Müller, Mitchell and de Zwaan2015). A prevalence meta-analysis has estimated a 4.9% pooled prevalence rate for CBD (Maraz et al., Reference Maraz, Griffiths and Demetrovics2015). Prevalence of CBD is also dependent on certain environmental factors: a market-based economy, easy access to a wide variety of goods, disposable income and consumerist values (Unger et al., Reference Unger, Papastamatelou, Yolbulan Okan and Aytas2014). Individuals with CBD describe a pre-occupation with shopping, increasing levels of urges or anxiety before purchasing and a sense of relief after purchase completion (Black, Reference Black2007). Shopping is shaped by positive and negative reinforcement contingencies and is used as a maladaptive strategy to improve mood (Lejoyeux and Weinstein, Reference Lejoyeux and Weinstein2010), cope with stress (Karim and Chaudhri, Reference Karim and Chaudhri2012), gain social approval/recognition (McQueen et al., Reference McQueen, Moulding and Kyrios2014) and to improve poor self-image (Roberts et al., Reference Roberts, Manolis and Pullig2014). The adverse consequences of CBD are large financial debts, legal issues, interpersonal difficulties, relationship problems and pronounced shame/guilt (McElroy et al., Reference McElroy, Keck and Phillips1995; Miltenberger et al., Reference Miltenberger, Redlin, Crosby, Stickney, Mitchell and Wonderlich2003; O’Guinn and Faber, Reference O’Guinn and Faber1989; Schlosser et al., Reference Schlosser, Black, Repertinger and Freet1994).

Despite the impact of CBD being typically negative, attempts to stop compulsive buying without help unfortunately typically tend to fail (Konkolý Thege et al., Reference Konkolý Thege, Woodin, Hodgins and Williams2015) and so treatment interventions have been developed. The current CBD treatment evidence base consists mainly of unscientific qualitative case reports, with a limited number of uncontrolled and controlled group designs. A range of modalities have been used to treat CBD including individual psychotherapy (Krueger, Reference Krueger1988; Winestine, Reference Winestine1985), family therapy (Park et al., Reference Park, Cho and Seo2006) and experiential therapy (Klontz et al., Reference Klontz, Bivens, Klontz, Wada and Kahler2008). The most tested approach to treating CBD is that of cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) delivered both individually and also in groups, with the group version implementing a manualised approach. Two qualitative case studies (Braquehais et al., Reference Braquehais, Del Mar Valls, Sher and Casas2012; Marčinko and Karlović, Reference Marčinko and Karlović2005) described the effectiveness of CBT when integrated with anti-depressant treatment, with one further case report (Kellett and Bolton, Reference Kellett and Bolton2009) describing the durability of an effective CBT intervention on CBD. Four studies have examined the effectiveness of group CBT for CBD and found evidence of significant improvements following treatment, across both uncontrolled and controlled methodologies (Filomensky and Tavares, Reference Filomensky and Tavares2009; Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Burgard, Faber, Crosby and de Zwaan2006; Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Mueller, Silbermann, Reinecker, Bleich, Mitchell and de Zwaan2008; Müller et al., Reference Müller, Arikian, Zwaan and Mitchell2013).

Hague et al. (Reference Hague, Hall and Kellett2016) reviewed the CBD treatment evidence base to conclude that the majority of studies were of methodological poor quality, lacked active comparator conditions, inconsistently used standardised CBD outcome measures and generated high drop-out rates. Hague et al. (Reference Hague, Hall and Kellett2016) suggested that the integrity of the CBD outcome evidence base could be improved by completing better methodologically designed studies of routine practice. Therefore, the current study utilised single case experimental design (SCED; Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Nock and Hersen2009) conducted in routine clinical practice. As clinical dilemmas arise from implementing methodologically rigorous but ethically suspect withdrawal designs (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Nock and Hersen2009), this study rather sought to implement an alternating treatment design (Manolov and Onghena, Reference Manolov and Onghena2018), with cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) and person-centred experiential counselling (PCE) as treatment comparators. No previous SCEDs of the treatment of CBD have been completed, despite the calls for such research (Lourenço Leite et al., Reference Lourenço Leite, Pereira, Nardi and Silva2014). The study hypotheses were: (1) both CBT and PCE would be effective compared with baseline on ideographic measures, (2) CBT and PCE will be equally clinically effective on ideographic measures, (3) reliable and clinically significant reductions would occur on nomothetic outcome measures and (4) no relapse would occur.

Method

Design

Ethical approval for the conduct of the study was achieved (reference no. 029105). The current study utilised a cross-over ABC plus extended follow-up SCED. The duration of the baseline ‘A’ phase was 4 weeks (n = 28 daily measurements), consisting of three assessment sessions. The ‘B’ phase consisted of thirteen 50-minute CBT out-patient sessions that lasted for 23 weeks (n = 160 daily measurements). The ‘C’ phase entailed six 50-minute PCE out-patient sessions that lasted for 9 weeks (n = 63 daily measurements). The follow-up phase lasted for 14 weeks and there was a single session completed at the end of this phase (n = 99 daily measurements). There was no therapeutic contact during 3-month follow-up.

Diagnosis

The patient was assessed using the Minnesota Impulsive Disorders Interview (MIDI; Christenson et al., Reference Christenson, Faber and de Zwann1994) as there is clinical consensus that an accurate diagnosis of CBD requires direct clinical assessment (Black, Reference Black, Mueller and Mitchell2011). For CBD, the questions on the MIDI reflect the impulse control disorder criteria of increasing tension before shopping, followed by relief after purchase and then evaluates related distress and impairment. The patient’s MIDI screen was positive for CBD, but no other impulse control disorder. To ensure the validity of CBD diagnosis, three other clinical measurements were used: the CBD criteria developed by McElroy et al. (Reference McElroy, Keck, Pope, Smith and Strakowski1994), the Compulsive Buying Scale (CBS; Faber and O’Guinn, Reference Faber and O’Guinn1992) and the Compulsive Acquisition Scale (CAS; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Kim, Morris, Bloss, Murray-Close and Steketee1998). At assessment, the patient scored in the caseness range on the CBS and the CAS-buy (see Table 3) and met the McElroy et al. (Reference McElroy, Keck, Pope, Smith and Strakowski1994) diagnostic criteria, due to describing shopping as being (a) uncontrollable, (b) time-consuming and resulting in forensic and financial difficulties and (c) not occurring only in the context of hypomanic or manic symptoms.

Participant

The patient was a 40-year old married women, who was seeking psychological help with CBD due to forensic problems. The patient had created a complex scam in which clothes would be purchased at a discount and returned for a full refund. The companies involved had become aware of this and the patient was arrested and charged by the police, and also banned from her local shopping mall. The patient reported a great sense of shame in relation to the arrest and ban, and this was the prompt for seeking psychological help. The patient had not received any prior psychological interventions and was not prescribed any medication throughout the course of the study. The patient was employed in a full-time position in retail banking.

The patient was brought up in a nuclear family and had one identical twin sister and two other sisters. She denied any major attachment issues with her parents or developmental trauma. The patient stated however that there was a ‘family culture’ of shopping and that shopping had always been modelled to her as a desirable and pleasant activity. The patient reported a sense of dependency and merger with her twin, which had been apparent across her life. The focus of this merger was particularly in relation to shopping and buying clothes. The patient stated that this was the ‘glue’ in the relationship with the sister, and that they would frequently shop together and compulsively buy for each other. Boundy (Reference Boundy and Benson2000) defined the sub-criteria of ‘co-dependent compulsive buying’, with excessive shopping being driven by the desire to buy for others, in the effort to win approval, love and also to avoid possible imagined rejection.

The patient described a lifelong pre-occupation with shopping and buying. The patient reported that she tended to spend most of her spare time shopping, that she tended to shop on a daily basis (i.e. ‘it’s a way of life’) and that shopping was her sole hobby (i.e. described as ‘all consuming’). The patient would spend long periods of time buying online, trying on clothes and returning them. The patient tended to also minimise and hide her buying at other times and would shamefully sneak purchased clothes and objects into the home and hide them from her husband. The patient reported using shopping as a means to control her emotions, and as a ‘tonic’ if she were feeling depressed or anxious. She stated that she experienced a climbing sense of tension (with associated feelings of physiological arousal) whilst shopping, urges to buy and a sense of a buzz on the point of purchase (and an associated change in her physiological arousal; stated as ‘a massive rush’). She would at times buy multiple versions of the same item to experience the arousal state in the same shopping trip. When shopping for long periods, the participant stated that she would enter a dissociated state and would walk around ‘as if in a daze’. The patient stated that she often spent significant amounts of her income on clothes and that she had large credit card debts. She stated that she felt helpless in the face of the overwhelming impulse to buy. She stated that shopping was a source of esteem from others, as others would relate to her as an ‘expert shopper’ and so would also be sent shopping to buy for her family and friends. She stated that the shopping had fused with her identity stating that ‘shopping is a big part of who I am’.

Treatment: descriptions and competency assessments

The opportunity to create an alternating treatment ABC SCED arose because the patient was waiting for the court hearing in relation to the alleged crime, and wanted to continue to access psychological support up to that point. Therefore, this provided the opportunity to change the treatment from CBT to PCE in order to provide support (but also change modality), with the follow-up phase being in the post-court period. The 13 sessions of CBT were based on the CBT treatment manual for CBD (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell, Müller and Mitchell2011). The first unit (CBD psychoeducation) was replaced by an idiosyncratic case formulation based on the Kellett and Bolton (Reference Kellett and Bolton2009) model, which was able to therefore formulate the role of the co-dependency (see Fig. 3 in the online Supplementary material). The remaining units consisted of: (2) problem buying consequences, (3) cue awareness, (4) cash management, (5) responses in terms of thoughts, feelings and behaviour, (6) cognitive restructuring, (7) cues and chains, (8) self-esteem, (9) exposure and (10) relapse prevention. The endings unit was not completed due to the patient progressing onto PCE. The sessions all started with creating a collaborative agenda, had the formulation visible, had a change method related to the unit and had homework exercises based on session content. The PCE (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Greenberg, Watson, Timulak, Freire and Lambert2013) was based on Rogerian concepts and therefore concerned the application of being congruent with the client, the therapist providing the client with unconditional positive regard, showing empathetic understanding and enabling depth emotional processing. Homework stopped during the PCE. Six sessions of PCE were delivered until the court hearing. Each active treatment phase was supervised by a different supervisor (i.e. a CBT supervisor supervised the CBT phase and a counsellor supervised the PCE phase).

Ideographic measures and analysis strategy

Seven ideographic measures were collected via a daily diary. The first three measures concerned behavioural indices of compulsive buying: (1) amount of money spent that day compulsively shopping, (2) duration of time that day spent compulsively shopping, and (3) duration of time that day spent talking about shopping with sister. The remaining four ideographic measures [scored on a 1 (not at all) to 9 (all the time) point Likert scales] regarded compulsive buying cognitions and emotions. Item 4 was a measure of shopping obsessions (‘shopping has been on my mind today’), item 5 was a measure of affective excitement (‘whilst shopping or thinking about shopping today, I felt a buzz’) and item 6 was a measure of strength of shopping compulsions (‘I felt compelled to shop today’) and item 7 measured CBD fusion with self-esteem (‘shopping or thinking about shopping made me feel good about me’).

Seven time-series graphs with baseline median trend lines fitted across the treatment and follow-up phases were created for the idiographic measures. Effectiveness of the CBT and PCE on ideographic outcomes was assessed using a range of non-overlap statistics: the percentage of data points exceeding the median (PEM; Ma, Reference Ma2006), the percentage of all non-overlapping data (PAND; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Hagan-Burke and Vannest2007) and non-overlap of all pairs (NAP; Parker and Vannest, Reference Parker and Vannest2009). Outcomes from the CBT, PCE and follow-up phases were combined and compared with baseline and PCE and CBT were also compared against each other. Non-overlap outcomes were interpreted as <70% (questionable/ineffective treatment), 70–90% (moderately effective treatment) and >90% (highly effective treatment; Wendt, Reference Wendt2009). Tau-U statistics were also used to assess difference between baseline and prospective phases. Tau-U refers to a family of statistics based on Kendall’s non-parametric, rank order coefficient (Brossart et al., Reference Brossart, Laird and Armstrong2018). Tau statistics were calculated for baseline trend, the difference between two phases (τAvsB provides a p-value identical to a Mann–Whitney test) and τ(AvsB)-Atrend that compares phases whilst adjusting for baseline trend. If the baseline trend is not significant, then τAvsB should be used over τ(AvsB)-Atrend (Brossart et al., Reference Brossart, Laird and Armstrong2018). Non-overlap statistics, tau-U and scatter plots were all performed using the Single Case Analysis plug-in (SCAN; Wilbert and Lueke, Reference Wilbert and Lueke2019) through R (R Core Team, 2019). If baseline phases on ideographic outcomes were stable, then τAvsB is a better index of outcome, as opposed to τ(AvsB)-Atrend. Binary logistic regression was also used to predict incidences of compulsive buying.

Nomothetic measures and analysis strategy

Five measures (two CBD and three generic outcome) were completed at baseline, end of CBT, end PCE and end of follow-up, as follows.

Compulsive Buying Scale (CBS; Faber and O’Guinn, Reference Faber and O’Guinn1992)

The CBS is a 7-item valid and reliable clinical screen for CBD and scores of <–1.34 index presence of compulsive buying (Faber and O’Guinn, Reference Faber and O’Guinn1992).

Compulsive Acquisition Scale (CAS; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Kim, Morris, Bloss, Murray-Close and Steketee1998)

The CAS is an 18-item measure of acquisition compulsions consisting of two subscales: compulsions to buy items and acquire free items. The CAS has been found to be both valid and reliable (Faraci et al., Reference Faraci, Perdighe, Monte and Saliani2018; Frost et al., Reference Frost, Steketee and Williams2002).

Beck Depression Inventory-II (BDI-II; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer, Ball and Ranieri1996a,b)

The BDI-II is a 21-item valid and reliable measure of the severity and intensity of depressive symptoms with scores coded as follows (Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer, Ball and Ranieri1996a,b): minimal depression (0–13), mild depression (14–19), moderate depression (20–28) and severe depression (29–63).

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-32 (IIP-32; Barkham et al., Reference Barkham, Hardy and Startup1996)

The IIP-32 is a measure of interpersonal functioning producing eight subscales (four that are done ‘too much’ and four that are ‘difficult to do’). The IIP-32 has good psychometric reliability and validity (Hughes and Barkham, Reference Hughes and Barkham2005).

Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI; Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1993)

The BSI is a 53-item measure of psychological distress incorporating three global indices: global severity index (GSI), positive symptom distress index (PSDI) and positive symptom total (PST). The BSI has good internal and test–re-test reliability, convergent, construct and discriminant validity (Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1993).

Nomothetic outcomes were evaluated using the Jacobson and Truax (Reference Jacobson and Truax1991) index of reliable and clinically significant change. The reliable change index (RCI) tests for the degree of change necessary in an outcome score for that change to be considered reliable, rather than that expected by chance. Change is classed as being clinically significant when outcomes shift from ‘caseness’ to ‘non-caseness’. Concurrent reliable and clinically significant change is classified as evidence of ‘recovery’ in practice-based contexts (Barkham et al., Reference Barkham, Stiles, Connell and Mellor-Clark2012). RCI calculations could not be conducted on the CBS due to the lack of necessary psychometric information (i.e. specifically, lack of any test–re-test evidence). The CBS was the primary nomothetic outcome measure for the study, due to this measure being commonly used to evaluate CBD outcomes in the treatment literature.

Results

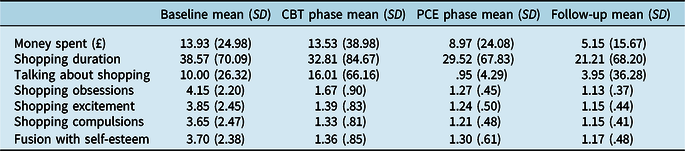

The results are divided into two sections. Section 1 describes the ideographic outcomes and section 2 details the nomothetic outcomes. Time series plots for the ideographic measures are clustered into behavioural (see Fig. 1) and cognitive/emotional (see Fig. 2). Table 1 provides the means and SD for ideographic measures according to phase of the study, Table 2 contains the results from the non-overlap analyses and Table 3 the nomothetic outcomes.

Figure 1. Behavioural CBD outcomes by phase of study.

Figure 2. Cognitive and emotional CBD outcomes by phase of study.

Table 1. Means and standard deviations for idiographic measure by phase of study

Table 2. Non-overlap results for ideographic outcomes by phase of study

*<.05, **<.001. 1Highly effective treatment; 2moderately effective treatment.

Table 3. Nomothetic outcomes by phase of study

RCI-1 is the assessment to end of CBT comparison, RCI-2 is the CBT to end of PCE comparison and RCI-3 is the PCE to follow-up comparison. Scores in bold indicate scores in clinical caseness at that point in time. Norms obtained from Frost et al., Reference Frost, Steketee and Williams2002 (CAS); Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Mitchell, Crosby, Gefeller, Faber, Martin, Bleichef, Glaesmerg, Exnerh and Zwaanaet2010 and Mitchell et al., Reference Mitchell, Burgard, Faber, Crosby and de Zwaan2006 (CBS community and clinical); Beck et al., Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1996b (BDI-II); Francis et al., Reference Francis, Rajan and Turner1990 (BSI; UK population norms); Derogatis, Reference Derogatis1993 (BSI; US out-patient norms); Barkham et al., Reference Barkham, Hardy and Startup1996 (IIP-32; UK norms). CBS, Compulsive Buying Scale; CAS, Compulsive Acquisition Scale; BDI-II, Beck Depression Inventory-II; BSI, Brief Symptom Inventory; GSI, Global Severity Index; PDSI, Positive Symptom Distress Index; PST, Positive Symptom Total; IIP-32, Inventory of Interpersonal Problems-32.

Behavioural ideographic CBD outcomes

In terms of incidence of compulsive buying, this occurred on 39.29% of baseline days (i.e. 11/28 days), 16.88% of CBT phase days (i.e. 27/160 days), 15.87% of PCE phase days (i.e. 10/63 days) and 13.13% of follow-up days (i.e. 13/99 days). In terms of incidence of talking about shopping, this occurred on 42.85% of baseline days (i.e. 12/28 days), 19.38% of CBT phase days (i.e. 31/160 days), 6.35% of PCE phase days (i.e. 4/63 days) and 3.03% of follow-up days (i.e. 3/99 days). Time spent compulsive buying was approximately 40 minutes per episode during the baseline, which fell to 30 minutes per episode during the active treatment phases and approximately 20 minutes per episode during follow-up days.

The binary logistic regression that predicted compulsive buying incidence (i.e. whether compulsive buying occurred or not) from baseline compared with CBT, PCE and follow-up phases was significant, χ 2 (3) = 8.93, p = .03, with the Nagelkerke pseudo R² (indicating the goodness of fit of the logistic regression model) being .042 (i.e. explaining 42% of the variance in incidents of compulsive buying). The model correctly predicted 82.60% of incidents of compulsive buying. CBT had a significant effect on reduced incidence of compulsive buying [Wald χ² (1) = 6.92, p = .009], as did PCE [Wald χ² (1) = 5.65, p = .017] and follow-up [Wald χ² (1) = 8.87, p = .003]. The odds in favour of not compulsively buying were .31 times higher during CBT, .29 times higher during PCE and .23 times higher during follow-up.

Baseline phases for behavioural ideographic CBD outcomes were stable in terms of money spent (τ = –.042, p = .752), shopping duration (τ = .037, p = .782) and time spent talking about shopping (τ = –.138, p = .304). PAND and some NAP results illustrated that CBT and PCE were highly effective in reducing the money spent compulsively, the time spent shopping and also the time spent talking about shopping. When the follow-up phase was compared with baseline on these behavioural indices, then there was evidence of a highly effective intervention. The Taua-b results between baseline and all other phases was significant for reduced money spent (τ = –.227, p = .046) and reduced time spent talking about shopping (τ = –.339, p = .003), but not for time actually spent compulsively shopping (τ = –.1.54, p = .176). When the PCE and the CBT phases were compared on behavioural ideographic outcomes, there were few apparent differences on the non-overlap results.

Cognitive and emotional ideographic CBD outcomes

There were stable baselines with regard to shopping obsessions (τ = .138, p = .304), shopping excitement (τ = –.048, p = .722), shopping compulsions (τ = .013, p = .921) and the sense of CBD fusion (τ = .037, p = .782). NAP, PEM and PAND results illustrate that CBT and PCE were moderate to highly effective interventions for reducing shopping obsessions, shopping compulsions, excitement about shopping and sense of fusion with shopping. When the follow-up phase was compared with baseline, then a moderately to highly effective intervention had taken place. Taua-b statistics between baseline and all other phases were significant for reduced shopping obsessions (τ = –.718, p = <.001), shopping compulsions (τ = –.601, p = <.001), shopping excitement (τ = –.705, p = <.001) and shopping fusion (τ = –.6.51, p = <.001). When the PCE and the CBT phases were compared, there were again few differences on the ideographic non-overlap results. The exception to this trend was for shopping obsessions, which indexed a significant reduction during PCE when compared with CBT (τ = –0.235, p = .006)

Nomothetic CBD outcomes

The CBS scores indicate that the participant no longer met the criteria for CBD at the end of CBT, improved on this progress following completion of PCE and improved again at follow-up. There was a reliable reduction in compulsive buying (CAS-Buy) comparing assessment with end of CBT, no further change to end of PCE and then a further reliable reduction at follow-up. There were no reliable or clinically significant reductions in the compulsive acquisition of free objects (CAS-Free) over time. The CAS-Buy results would suggest recovery by the end of the follow-up period.

Nomothetic mental health outcomes

There was a reliable reduction in depression (BDI-II) from assessment to end of CBT, but a reliable increase in depression at the end of PCE. Baseline to follow-up comparisons indexed a reliable and clinically significant reduction in depression. There was no reliable reduction in psychological distress (BSI-GSI) from assessment to end of CBT. There was an observed increase in distress comparing the end of CBT with the end of PCE, at which the patient reached clinical caseness. There was a reliable and clinically significant reduction in psychological distress from PCE termination to follow-up, with the patient no longer reaching caseness on the BSI-GSI at follow-up. There was a reliable increase in interpersonal problems (IIP-32) from assessment to end of CBT, and then no further change from end of CBT to the end of PCE, and end of PCE to final follow-up. The BDI-II and BSI-GSI results would suggest recovery by the end of the follow-up period.

Discussion

This has been the first study to evaluate the effectiveness of CBT for CBD with a SCED, with the method containing both a comparative cross-over treatment phase and an extended follow-up phase to add to the internal validity of the study (Barlow and Hersen, Reference Barlow and Hersen1984). This research adds to and extends the extant CBT evidence base, which has previously tended to focus on evaluations of group treatments, and the results are in line with the positive outcomes described for CBT (Hague et al., Reference Hague, Hall and Kellett2016). The results demonstrated a moderately to highly effective intervention for cognitive and emotional ideographic CBD outcomes and a less effective intervention for the behavioural ideographic CBD outcomes. In terms of a very basic analysis of outcome, then the time spent compulsively shopping had halved when the baseline was compared with the follow-up. It has been argued that complete abstinence or elimination of CBD behaviours is unrealistic, with treatment therefore focusing more on the management of problematic shopping and spending behaviours (Benson and Eisenach, Reference Benson and Eisenach2013). The only moderately effective financial results could be viewed with clinical concern, as 89% of CBD patients report excessive ongoing CBD-related debt (Schlosser et al., Reference Schlosser, Black, Repertinger and Freet1994).

The reductions to shopping obsessions, excitement associated with shopping, shopping compulsions and CBD fusion with self-esteem were founded on stable baselines, suggesting that change was therefore not purely the result of therapist contact. Stable baselines are a key component of SCED (Barlow et al., Reference Barlow, Nock and Hersen2009; Morley, Reference Morley2018), as unstable baselines undermine confidence in any subsequent changes detected in response to intervention or withdrawal (McMillan and Morley, Reference McMillan, Morley, Barkham, Hardy and Mellor-Clark2010). With impulse control disorders such as CBD (Robbins and Clark, Reference Robbins and Clark2015), then perhaps it is better to expect a pattern of stable instability, rather than pure stability during baseline phases. The introduction of the case formulation appeared to signal a sudden insight gain for the participant that was translated into behavioural and cognitive changes. The therapeutic impact of case formulation has been observed previously in SCED studies (for an example, see Curling et al., Reference Curling, Kellett, Totterdell, Parry, Hardy and Berry2018). It is worth noting that across all the ideographic outcome measures, there was no evidence of deterioration or relapse across the follow-up period. This suggests that durable CBD self-management skills had been learnt by the patient.

The CBD-specific nomothetic outcomes would suggest that the patient was in the community sample by the end of the follow-up period and therefore that clinically significant change had occurred. Across the nomothetic outcome measures of depression (BDI-II), psychological distress (BSI-GSI), symptom severity (BSI-PDSI) and interpersonal problems (IIP-32), it was observed that deterioration occurred at the end of the PCE phase. This deterioration seemed to reflect the external stress factors that the patient was experiencing during this period, but it is interesting to note that the intervention appeared to insulate the patient from concurrent CBD relapse. As stated, the opportunity to turn the study into an ABC design arose due to the fact that the patient had an impending court appearance and wanted to continue to access support during this period. It is therefore probable that these forensic problems resulted in the observed increases in depression, psychological distress, symptom severity and interpersonal problems during this period. There was evidence of recovery on these measures by the end of the follow-up period.

Study limitations

As this study was a SCED, then the results may not easily generalise to other CBD patients. As all the measures were self-report, then outcomes may have been unduly influenced by response and/or social disability bias (Rosenman et al., Reference Rosenman, Tennekoon and Hill2011). The study could be criticised for the length of the follow-up period. The CBS (i.e. the primary nomothetic outcome measure) has been criticised on the grounds of item face validity (Edwards, Reference Edwards1993). The lack of a follow-up administration of the MIDI is a study limitation (Christenson et al., Reference Christenson, Faber and de Zwann1994). Considering the dissociation described during compulsive shopping episodes, then adding in an ideographic and nomothetic measure of dissociation would have been useful. There is an obvious issue with the ordering of phases, as it was not possible to clarify if the observed outcomes would have been different if the order of treatments had been reversed, (i.e. ‘B’ = PCE and ‘C’ = CBT). The decision to deliver the CBT first was based on awareness of the evidence base for CBT (Hague et al., Reference Hague, Hall and Kellett2016) and so to withhold CBT as the first phase of treatment would have been potentially unethical. Ninan et al. (Reference Ninan, McElroy, Kane, Knight, Casuto, Rose, Marsteller and Nemeroff2000) conducted a trial of fluvoxamine in treating compulsive buying and reported a high placebo-response rate that was ascribed to the behavioural benefits of keeping a daily diary. This is also known as the mere measurement effect (Morwitz and Fitzsimons, Reference Morwitz and Fitzsimons2004). The baselines in the current study were stable, however, which would mitigate against this effect being apparent in the current study.

Future research

The CBD outcome evidence base would benefit from conducting a case series with a counterbalanced ABC design. An ABC with counterbalancing entails half of the participants being randomly assigned to receive B (i.e. CBT) and then C (i.e. PCE), whilst the other half receives C (i.e. PCE) and then B (i.e. CBT). Introducing counterbalancing for the order of treatment delivery helps to rule out alternative explanations of outcome (McMillan and Morley, Reference McMillan, Morley, Barkham, Hardy and Mellor-Clark2010). Whilst this is a methodologically appropriate means of investigating CBD outcome, it also raises ethical issues concerning withholding a potentially effective intervention, or removing a treatment that is already working (Rizvi and Nock, Reference Rizvi and Nock2008). The more recently developed Pathological Buying Screener (Mueller et al., Reference Mueller, Trotzke, Mitchell, de Zwann and Brand2015) may be a better choice of primary nomothetic outcome measure in future studies, due to its more extensive psychometric evaluation. Future research could also collect data from informants other than the patient to reduce threats from response and/or social disability bias to the internal validity of the study (e.g. Kellett and Totterdell, Reference Kellett and Totterdell2013).

Conclusion

As the first SCED evaluating the treatment of CBD, this study has strengthened the CBD treatment evidence base, by providing an intricate longitudinal evaluation of the effectiveness of CBT against an active PCE comparator. For the CBD treatment outcome evidence base to progress, the methodological quality of such small scale practice-based designs needs to improve, and also be used as a foundation from which to design more controlled clinical trials (Hague et al., Reference Hague, Hall and Kellett2016). Measuring change to financial functioning appears vital in any evaluation of CBD treatment outcome. Overall, active intervention in this study was effective, but there were few differences between the modalities. The next research step for the CBT CBD evidence base might be to conduct a SCED in which behavioural and cognitive change methods are systematically introduced or removed, in order to assess their relative contribution. The evidence base for intervention in CBD clearly requires more work across all the psychotherapeutic modalities.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465820000521

Acknowledgements

With thanks to the participant for collecting the data.

Financial support

None.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.