Introduction

Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) has been recommended as an effective treatment for a range of common mental health difficulties such as depression, anxiety and panic (NICE, 2009, 2004). A key issue is how to provide access to evidence-based psychological therapies such as CBT (Layard, Reference Layard2006). There are currently just over 1200 practitioners who are accredited in the UK by the lead body for CBT, the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapies (BABCP, 2009). As a consequence, access to specialist CBT is limited to a highly selected number of patients and waiting lists have become commonplace for CBT.

Influential reviews (Lovell and Richards, Reference Lovell and Richards2000) and the NICE guidelines for depression (NICE, 2009) and anxiety (NICE, 2004) have all recommended that cognitive behavioural self-help (CBSH) approaches be considered as a first step in treatment for common mental health disorders such as depression and anxiety. These disorders are very common in the general population. Epidemiological data in the UK have shown a combined prevalence rate of 16.4% for anxiety and depression in adults (16–74 years old) living in private households in 2000 (Singleton, Meltzer and Jenkins, Reference Singleton, Meltzer and Jenkins2003).

CBSH can be delivered in different ways, including written workbooks (bibliotherapy), computerized CBT, or via video/audio tapes or DVDs. The self-help approach promotes personal responsibility for one's own health and well being and is particularly effective when the self-help approach is supported by short-term interventions from a trained practitioner (Gellatly et al., Reference Gellatly, Bower, Hennessy, Richards, Gilbody and Lovell2007). UK services are being widely redesigned to introduce these ways of working both at Primary and Secondary Care level. No courses to date have been available that focus on providing training in the delivery of evidence-based CBSH materials. The development of these types of courses is important, as the delivery of programmes to increase access to psychological therapies have workforce planning, education and training implications (Department of Health, 2003).

The current specialist one-year postgraduate CBT courses mainly address specialist level CBT. They are expensive both in terms of financial cost, and in terms of the time commitment to complete them. It is likely that there will never be enough fully accredited practitioners to meet demand for CBT (Layard, Reference Layard2006).

The delivery of CBSH, can be supported by health workers, of a variety of backgrounds, who have achieved a level of competency and understanding of CBSH practice. In England, the Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) program addresses a new workforce that is being trained to deliver both high and low intensity CBT interventions at the primary care and community level. In contrast, we describe a training initiative within the existing workforce that aims to introduce CBSH interventions into everyday clinical practice. We describe the delivery and evaluation of the course and believe this is the only UK-based CBSH course that is accredited by external universities. The aim of this study is to evaluate the impact of training on community and inpatient-based mental health staff in the use of CBSH.

Method

Study design

This study has a pre–post design. Participants were assessed at baseline, again following the training intervention, and finally at 3 months post training. Baseline knowledge and skills and use of a problem-focused clinical assessment were evaluated using self-report questionnaire. Objective knowledge and skills were assessed during, immediately after, and 3 months after training. Ongoing use of CBSH was also evaluated at 3 months post training.

Setting and participants

The current study reports on the training of 17 Mental Health Teams (16 adult and 1 old age) in Glasgow. Overall, 287 people have started the training; 20 dropped out after the initial pre-meeting, with 267 completing the course. Of the 267 attendees, only 15 individuals failed to attend at least 70% of the sessions – the level of attendance necessary to receive a course completion certificate.

Out of the 267 attendees, 19% were in-patient based, 76% community based, and 5% were both inpatient and community based. The professional backgrounds of the participants included nursing, clinical psychology, social work, medical, and other allied medical professions.

Intervention: the SPIRIT course

The SPIRIT (Structured Psychosocial InteRventions in Teams) course trains practitioners in the use of a series of CBT self-help workbooks (Williams, Reference Williams2009). These materials have proven to be highly effective (effect size 1.27) in a large Primary Care based randomized controlled trial (Williams et al., Reference Williams, Morrison, Wilson, McMahon, Walker, Allan, Tansey and McNeill2007). The training is offered to all team members working within a single multi-disciplinary mental health team and must include staff from both inpatient and community settings. The team is trained together with the aim of encouraging in-house supervision, sustainability of application into practice of the training, and building upon multidisciplinary and multi-agency team-based working. Up to 20 staff from each team can attend the course.

The SPIRIT trainers comprise a number of mental health professionals who are seconded to the training project one day a week. Over half of them had completed a specialist CBT training course. Pairs of trainers deliver the training intervention to each of the allocated teams in order to provide consistency. To measure adherence, all trainers were independently rated as to their coverage of between 75–100 bullet points on the training slides on two occasions. Trainers adhered to the training slides at least 80% of the time.

Course content

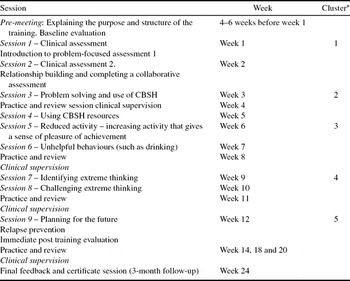

The SPIRIT course consists of 38.5 hours of workshops and 5 hours of clinical supervision termed “Practice and review”. It is delivered in nine 3.5 hours main workshop sessions, 5 one-hour-long sessions of practice and review, and a final 2-hour feedback and certificate session. The course content is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Session content

*Refers to the cluster of analysis presented in the results section.

Team members are encouraged to put into practice what they learn. Sessions start with 10 minutes of peer supervision and end with the planning of practice tasks to take place between the training sessions. The key focus of the training is to introduce a problem focused clinical assessment, which is then shared with the patient who receives a copy for their own use. This is based on the so-called five areas assessment model of CBT, which encourages practitioners to work with the patient to identify problems in five key domains/areas of their lives (situation, thinking, feelings, physical symptoms, and behaviour; Williams and Garland, Reference Williams and Garland2002). This is then linked to how to introduce and support CBSH materials that address the individual patient's needs. Learning within a team environment encourages the active discussion of cases, and explores how the learning can be implemented into the day-to-day practice of the clinical context.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

Training evaluation. We evaluated subjective and objective knowledge and skills gain as well as the training acceptability.

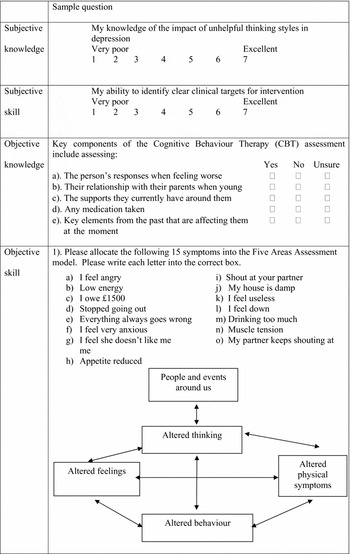

The evaluation of sustainability of knowledge and skills gain. Subjective ratings of knowledge and skill were recorded using self-report Likert-style scales (anchored at 1–7: very poor to excellent). These were designed by the authors to evaluate items specific to the current training intervention, and for which no previous questionnaires were available. Objective measures of knowledge and skill were measured using neutrally marked multiple choice questions and a range of practical clinical skills-based tasks, such as the identification of clinical symptoms and the completion of a problem-focused assessment. For example, objective skills are evaluated using a self-test task, asking participants to allocate 15 separate common mental health symptoms into five different clinical areas (thinking, feelings, physical symptoms, behaviour/activity, and environmental). A copy of the evaluation tool is available upon request from the authors. A sample of the type of questions used for each area is included in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Examples of the subjective and objective knowledge and skills assessments

Self-perceived subjective knowledge and skills of the core topics covered by the course were recorded at baseline and repeated immediately after the end of training and at 3 month follow-up to evaluate sustainability of any training gains. The 3-month evaluation also examined the use of the problem-focused clinical assessment and CBSH approach and reviewed the usefulness of the course. Objective practical skills were evaluated by asking attendees to carry out the same problem-focused clinical assessment at each time point. Objective knowledge was not included at the 3-month follow-up for sustainability as piloting showed practitioners found the number of questions unacceptable when asked for a third time.

Practitioners were asked to indicate at baseline, post-intervention and at 3-month follow-up whether or not they had used any of the practical skills addressed by the CBSH material with their patients in the preceding 2 weeks – summarized in Table 2.

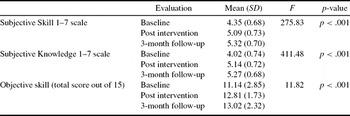

Table 2. ANOVA results for sustainability of skill and knowledge gains

The evaluation of training acceptability

Training delivery acceptability and content was measured using the Training Acceptability Rating Scale – TARS (Davis, Rawana and Capponi, Reference Davis, Rawana and Capponi1989). The TARS questionnaire is split into two sections: the first addresses training content (general acceptability, effectiveness, negative side-effects, appropriateness, consistency and social validity), and the second concerns the trainee's impressions of the teaching process and outcomes. This scale is widely used in educational settings and has good predictive validity and reliability. A rating of 70% is considered to be highly satisfactory, and above 80% is considered to be unusually good (Davis et al., Reference Davis, Rawana and Capponi1989).

Data analysis

We analyzed the data using the statistical package SPSS (version 15). The data were checked for normality and mean values compared using paired sample t-tests (for pre-post comparisons). To correct for the multiple t-tests performed, a Bonferroni corrected significance level (alpha/number of tests) was utilized (p < .002). The Chi squared test was used to compare frequencies/proportions. For the analysis of the sustainability of training gains at the 3-month follow-up we used a repeated measures ANOVA.

Results

Knowledge and skill gains

In order to analyze the knowledge and skills gains, a data analysis was undertaken, to produce a detailed analysis of each of the content clusters: “Clinical assessment” (sessions 1 and 2), “Problem-solving and self-help” (sessions 3 and 4), “Altered behaviours” (sessions 5 and 6), “Altered thinking” (sessions 7 and 8) and “Planning for the future” (session 9) before and after the intervention (see Table 1). The analysis shows improvements in all areas at the 0.001 alpha level, with the exception of objective knowledge and skill gain for the “Planning for the future” session. A detailed analysis in table format can be made available upon request from the authors.

Furthermore, an overall analysis of both the objective skills and the subjective knowledge and skills gains for the course was performed using an ANOVA test. The results show that not only was there pre-post intervention improvement in all areas (subjective skill, subjective knowledge, and objective skill), but these improvements were sustained at the 3-month follow-up (these results are summarized Table 3).

Table 3. Use of CBSH approach at post training and at 3-month follow-up

As well as the level of skill gains by participants, the evaluation of the course investigated the level of use of the approach immediately after the intervention and at the 3-month follow-up time point. Results are summarized in Table 3.

The greater the number of course sessions attended, the greater the use of the collaborative problem-focused clinical assessment approach (r = 0.198, p< .001). The use of the CBSH approach at the 3-month follow-up was assessed for each of the components of the intervention. Although in some individual items a significance level was obtained by small changes in values between pre, post and 3-month follow-up scores, overall there has been a significant increase in the use of CBSH approach, which was sustained at the 3-month follow-up (Table 3). The areas identified where the level of change was found to be lowest were for assertiveness training and overcoming reduced activity. The areas of greatest change in practice were identified for the use of the problem-focused clinical assessment and offer of relapse prevention interventions.

At 3 months, overall, 24% of attendees had used a problem-focused clinical assessment in the last week, and 40% of attendees reported using one or more CBSH workbooks per week. The number of people never giving out a written problem summary more than halved (from 50% to 20%) over this time period.

Experience of the training

At the 3-month follow-up the mean rating of usefulness of the training was 5 (SD 1.1) on a 7-point Likert scale, and 93% of those that responded (n = 202) reported that they would recommend the training. The TARS score was between 82–85% and between 66–71% for training content and process of training delivery respectively for all sessions. The global TARS score for all sessions combined was 83% and 68% respectively.

Discussion

The delivery of the stepped care model, as suggested in the NICE (2009) guidelines, has formally introduced the practice of delivering CBT self-help into clinical services across the UK. These changes have significant workforce development implications. To date no training courses have aimed to train practitioners to be competent and effective specifically in using CBSH.

The SPIRIT training programme was designed using a pragmatic approach, with delivery within existing NHS settings in mind. Team-based learning has been used together with an emphasis on “active learning”, encouraging participants to apply newly acquired knowledge to their current case-loads. The approach was also used to help facilitate the uptake and supervision of the new approach, and to promote the development of teamwork (King et al., Reference King, Davidson, Taylor, Haines, Sharp and Turner2002).

One of the challenges of any training intervention is increasing the uptake of the desired intervention into everyday clinical practice. The SPIRIT training package has shown that there has been an increase in use of the approach by participants; however, some elements of the intervention had greater levels of change in use than others. So the offer of a problem-focused clinical assessment and relapse prevention interventions showed the highest increase in use. However, the changes were lowest for the implementation of assertiveness training. This may be because this is not such a universally used intervention with all clients. Changes were also low for the use of the overcoming reduced activity (behavioural activation) element of the intervention; the small reported change may have been accounted for by the fact that the use of this intervention at baseline was already relatively high. This is important because overcoming reduced activity can be one of the most effective interventions for depression (Ekers, Richards and Gilbody, Reference Ekers, Richards and Gilbody2008).

To further improve the uptake and use of CBSH strategies, the issue that is being explored for future cohorts is the establishment of sustainable local CBSH supervision systems that extend beyond the time period of the training intervention. The course is focused on a competency-based learning approach, and uses practical sessions and supervision for trainers to ascertain the objective skills gains of the participants.

The SPIRIT training course has shown improvements in subjective knowledge and both subjective and objective skills, and these have been sustained over time. We did not evaluate directly the impact that the training had in its delivery format to the whole team, but the comments received from participants in the supervision sessions reflected that multi-professional learning and more specifically learning in teams was seen as a highly effective way of sustaining learning, and facilitating the introduction of new ways of working.

One of the weaknesses of the current evaluation is that although we have been able to evaluate outcomes from a learner's perspective, we have not evaluated the impact in therapeutic benefit or clinical change in clients or patients. This may be an area of potential future research.

Conclusions

The SPIRIT training programme aims to bridge a gap in the training of professionals in the use of CBSH. The SPIRIT training programme has proved to be successful both in terms of the knowledge and skills gains and also in the resulting change in clinical practice for its participants.

Perceived subjective skills and knowledge and objective skills ratings were significantly greater at both the final evaluation and 3-month follow-up compared with the baseline data. There was no significant difference in skills and knowledge gain when comparing the final evaluation and 3-month follow-up, which indicates that the training gains were sustained. The use of a problem-focused clinical assessment increased after the training, particularly with regards to providing patients with a written summary of their problem. Although many of the initial training gains in the use of practical CBSH skills were sustained at follow-up, the use of CBSH was modest (40%) at the 3-month follow-up. To further improve the uptake and use of CBSH strategies in future cohorts, more emphasis will be placed on establishing sustainable local supervision systems within the teams. The SPIRIT course is university accredited with Glasgow Caledonian University, with assessments of the practitioners' work being carried out through a portfolio based assessment. Benefits to personal CPD has also helped make the course attractive for practitioners.

Although there are still limitations, the SPIRIT training has gone a significant way towards increasing access to CBSH treatments. Participants in the training report use of the learnt skills in their own clinical settings. This is significant considering previous research suggesting that it is difficult to train practitioners in CBT for use in everyday clinical setting (King et al., Reference King, Davidson, Taylor, Haines, Sharp and Turner2002).

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank Professor Jill Morrison of the University of Glasgow for her advice in the design of the learning assessment. This project received funding from Modernizing Mental Health Project Funding, Greater Glasgow Health Board. Declaration of conflict of interest: Dr C. Williams has written various self-help books and training resources and receives royalties based on these. Finally, we thank Margret Watson and Susan Monks who have helped co-ordinate the SPIRIT training, and all the SPIRIT trainers.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.