Introduction

Psychosis affects 7.49 in every 1000 people (Moreno-Küstner and Martin, Reference Moreno-Küstner, Martin and Pastor2018), causes considerable distress and disability (Schizophrenia Commission, 2012, 2017), and is estimated to be the most costly of chronic conditions (Garis and Farmer, Reference Garis and Farmer2002).

One of the best evidenced psychological interventions, cognitive behavioural therapy for psychosis (CBTp) (van der Gaag et al., Reference van der Gaag, Valmaggia and Smit2014), targets the cognitive and behavioural factors maintaining delusions and hallucinations, with modest outcomes to date (Jones et al., Reference Jones, Hacker, Meaden, Cormac, Irving, Xia and Chen2018; Laws et al., Reference Laws, Darlington, Kondel, McKenna and Jauhar2018).

While cognitive theories of psychosis emphasise the reciprocal relationships between our thoughts, feelings and behaviours, CBTp fails to target emotion directly (Gumley et al., Reference Gumley, Gillham, Taylor and Schwannauer2013). The evidence suggests that for people vulnerable to psychosis, minor stressors trigger negative affect, which in turn increases likelihood of psychotic experience due in part to difficulties identifying, accepting and modifying emotion (Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Hartmann, Köther and Moritz2015a; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Sundag, Schlier and Karow2017). This hypothesis is supported by research demonstrating that stressors increase both negative affect and psychotic symptoms (Ellett et al., Reference Ellett, Freeman and Garety2008; Myin-Germes and van Os, Reference Myin-Germeys and van Os2007), and that negative affect immediately precedes increases in paranoia (Kramer et al., Reference Kramer, Simons, Wigman, Collip, Jacobs and Derom2014). Studies of emotion regulation indicate that, compared with healthy controls, people with psychosis are less aware of their emotions or able to understand them (Henry et al., Reference Henry, Bailey, von Hippel, Rendell and Lane2010; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Hartmann, Köther and Moritz2015a; O’Driscoll et al., Reference O’Driscoll, Laing and Mason2014), report higher levels of threat anticipation (Reininghaus et al., Reference Reininghaus, Kempton, Valmaggia, Craig, Garety, Onyejiaka, Gayer-Anderson, So, Hubbard, Beards and Dazzan2016), show greater stress sensitivity (Khoury and Lecomte, Reference Khoury and Lecomte2012; Llerena et al., Reference Llerena, Strauss and Cohen2012), and are less able to tolerate distress (Nugent et al., Reference Nugent, Chiappelli, Rowland, Daughters and Hong2014). People with psychosis are also more likely to rely on maladaptive emotion regulation strategies (e.g. emotion suppression and rumination) and have difficulty implementing adaptive responses (e.g. acceptance and cognitive reappraisal) (Kimhy et al., Reference Kimhy, Vakhrusheva, Jobson-Ahmed, Tarrier, Malaspina and Gross2012; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Hartmann, Köther and Moritz2015a; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Hartmann, Köther and Moritz2015b; Nittel et al., Reference Nittel, Lincoln, Lamster, Leube, Rief, Kircher and Mehl2018; O’Driscoll et al., Reference O’Driscoll, Laing and Mason2014; Perry et al., Reference Perry, Henry and Grisham2011). A recent systematic review of emotion regulation in people with psychosis found that, compared with non-clinical controls, this group had greater difficulties in identifying, describing and understanding emotions; accepting emotions; engaging in goal directed behaviour when distressed; and willingness to experience distress in pursuit of meaningful activity (Lawlor et al., Reference Lawlor, Hepworth, Smallwood, Carter and Jolley2020). These authors highlight the need for targeted interventions to facilitate emotional regulation in people with psychosis.

Dialectical behavioural therapy (DBT) is a skills-based therapy, developed for people with emotion regulation difficulties, and yields good outcomes for people with diagnoses of emotionally unstable personality (Cristea et al., Reference Cristea, Gentili, Cotet, Palomba, Barbui and Cuijpers2017; Panos et al., Reference Panos, Jackson, Hasan and Panos2014), addictions (Linehan et al., Reference Linehan, Schmidt, Dimeff, Craft, Kanter and Comtois1999, Reference Linehan, Dimeff, Reynolds, Comtois, Welch, Heagerty and Kivlahan2002), eating disorders (Lenz et al., Reference Lenz, Taylor, Fleming and Serman2014; Bankoff et al., Reference Bankoff, Karpel, Forbes and Pantalone2012), attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (Cole et al., Reference Cole, Weibel, Nicastro, Hasler, Dayer, Aubry and Perroud2016; Fleming et al., Reference Fleming, McMahon, Moran, Peterson and Dreessen2015; Hirvikoski et al., Reference Hirvikoski, Waaler, Alfredsson, Pihlgren, Holmström, Johnson and Nordström2011) and depression (Harley et al., Reference Harley, Sprich, Safren, Jacobo and Fava2008). To our knowledge, there are no controlled trials examining DBT in people with psychosis.

We now have good evidence that psychosis is associated with emotion regulation difficulties. To date, there are no studies examining the corollary, that practising emotion regulation skills ameliorates psychotic symptoms. Single case studies can be used to examine the impact of these skills for people with psychosis. Single case methodology is particularly well suited to examining theory-driven hypotheses about the relationships between interventions and outcomes (Persons and Boswell, Reference Persons and Boswell2019), and the development of new treatment targets (Morley, Reference Morley2018).

We used an ABA design to examine changes in emotion regulation, affect and paranoia over time. If skills rehearsal proved to be beneficial, emotion regulation strategies might be incorporated in psychological treatments to improve outcomes.

Method

Design

We used a single case series ABA design, and collected data over baseline, intervention and withdrawal of intervention phases (Kazdin, Reference Kazdin2019) to minimise the impact of extraneous variables and so increase the validity of inferential findings (Morley, Reference Morley2018). We followed best practice (Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2013), reporting (Tate et al., Reference Tate, Perdices, Rosenkoetter, Wakim, Godbee, Togher and McDonald2013), and statistical analysis guidelines for single case methodology (Morley, Reference Morley2018; Shadish, Reference Shadish2014).

Participants

Of the 14 people who attended the assessment session, met criteria and were consented, two were unable to continue due to changed personal circumstances, and five missed more than three sessions so were considered non-completers. Seven participants (three females, three males, one gender non-binary) completed the study. Participants were recruited from Early Intervention for Psychosis (EIP) and Community Adult Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) across the south of England. Participants met criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as assessed by their consultant psychiatristFootnote 1 following the International Classification of Diseases-10 (APA, 1992). Six people identified as White British and one as White European. Table 1 gives demographic, service and presentation information.

Table 1. Demographic, service and presentation information

EIP, Early Intervention in Psychosis team; CMHT, Community Mental Health Team; all participants attended all ten sessions.

Measures

Emotion regulation

The Difficulties in Emotion Regulation Scale (DERS; Gratz and Roemer, Reference Gratz and Roemer2004) assesses the capacity to regulate emotion in treatment-seeking populations. The scale consists of 36 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (almost never) to 5 (almost always), and yields six subscales: non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. Higher scores indicate greater difficulties with emotion regulation. The subscales have good internal consistency (α > .80).

The Distress Tolerance Scale (DTS; Simons and Gaher, Reference Simons and Gaher2005) assesses ability to withstand negative emotional states. The scale consists of 15 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree), yielding four subscales: ability to tolerate, appraise, absorb and regulate distress. Higher scores indicate greater difficulties tolerating negative emotion. The subscales have excellent internal consistency (α > .90).

Affect

The Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al., Reference Watson, Clark and Tellegen1988) assesses current emotion. Twenty emotions are rated ‘at the moment’ on a 5-point scale from 1 (slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely). Higher scores indicate more intense current emotion on the two subscales of positively valenced and negatively valenced affect. The subscales have good internal consistency (α > .85).

Paranoia

The Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale (GTPS; Green et al., Reference Green, Freeman, Kuipers, Bebbington, Fowler, Dunn and Garety2008) assesses trait paranoia. The scale consists of 32 items rated on a 5-point scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (totally), and yields two subscales: ideas of reference and ideas of persecution. Higher scores indicate greater trait paranoia. The scale has excellent internal consistency (α = .90).

The Paranoia Checklist – state version (PC-state; Schlier et al., Reference Schlier, Moritz and Lincoln2016) was adapted from the original Paranoia Checklist (Freeman et al., Reference Freeman, Garety, Bebbington, Smith, Rollinson, Fowler, Kuipers, Ray and Dunn2005) to assess state paranoia. Five items are rated ‘at the moment’ on an 11-point scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (very much). Higher scores indicate greater state paranoia. The scale has good internal consistency (α = .83).

Emotion regulation intervention

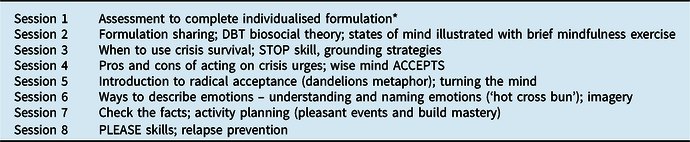

Our eight session intervention included two assessment and formulation sessions (to facilitate engagement and develop an individualised rationale for the intervention), followed by six sessions of emotion regulation skills rehearsal, drawn from the DBT literature without adaptation (see Table 2). Skill acquisition relies on regular practice, to facilitate learning and appropriate application. For example, in DBT, people attend two regular sessions each week – individual and group therapy. For this reason we offered twice weekly sessions.

Table 2. Content of sessions

For detail of skills and acronyms, see Linehan (Reference Linehan2014). *Following Newman-Taylor and Stopa (Reference Newman-Taylor and Stopa2013).

Procedure

Participants were informed of the study by their primary clinician. Those who expressed an interest were provided with full details and gave informed consent. They then completed the five measures of emotion regulation, affect and paranoia. Participants repeated all but the trait paranoia measure every other day for two weeks (baseline phase). They then attended eight, twice weekly, hour-long intervention sessions, and continued to complete the measures every other day (intervention phase). Following withdrawal of the intervention, participants continued to complete the measures for two further weeks (follow-up phase)Footnote 2 . At a final review session, participants repeated the trait paranoia measure, and were given a small honorarium for their time and travel expenses. The time involved included the eight hour-long sessions and ~15 minutes every other day to complete the measures across baseline, intervention and follow-up phases.

Data analysis plan

In single case studies, analyses are conducted per participant, and typically combine visual inspection of the data, and statistical analysis of patterns within and across phases, to reduce risk of bias (Kratochwill and Levin, Reference Kratochwill, Levin, Kratochwill and Levin2014; Morley, Reference Morley2018; Ottenbacher, Reference Ottenbacher1993). Visual exploration of the data was completed by plotting data points alongside the broadened median for each phase, to reduce the impact of extreme scores (Morley, Reference Morley2018). The Tau-U test was used to calculate statistical differences in scores between phases; this is considered more sensitive than mean or median differences (Huberty and Lowman, Reference Huberty and Lowman2000; Parker et al., Reference Parker, Vannest, Davis and Sauber2011) and controls for any lack of central tendency, i.e. data that tend up or down within a phase (Wilcox and Keselman, Reference Wilcox and Keselman2003). The intervention is deemed to have had an impact if one or both of these approaches indicates change between phases that is not accounted for by trends within preceding phases; statistical analyses supplement but do not trump visual inspection of data in single case research (Morley, Reference Morley2018).

Results

Participant characteristics

At the start of the intervention, all participants scored within one SD of the clinical mean (or higher) for trait paranoia on both social reference and persecution subscales. Trait paranoia scores pre- and post-intervention are shown in Table 3.

Table 3. Trait paranoia scores before and after emotion regulation skills rehearsal

Social reference non-clinical mean = 26.8 (SD 10.4); clinical mean = 46.4 (SD 16.4); persecution non-clinical mean = 22.1 (SD 9.2); clinical mean = 55.4 (SD 15.7) (Green et al., Reference Green, Freeman, Kuipers, Bebbington, Fowler, Dunn and Garety2008).

Changes across phases

Figure 1 shows emotion regulation, affect and paranoia across phases, for each participant. Footnote 3

Figure 1. Emotion regulation, affect and paranoia across phases.

Participant A

Visual analysis of the data indicates improved emotion regulation (DERS and DTS), reduced negative affect, and increased positive affect, across phases. State paranoia was very low by the start of the intervention. The Tau-U statistics show reductions in the DTS (u = −.93, z = −3.01, p < .01), DERS (u = −1.00, z = −3.24, p < .01), negative affect (u = −.89, z = −2.99, p < .01) and paranoia (u = −.95, z = −3.20, p < .01) between baseline and follow-up.

Participant B

Visual analysis suggests improved emotion regulation (DERS) and reduced paranoia across phases. A modest decrease in negative affect between baseline and intervention is not maintained at follow-up. The Tau-U statistics show a reduction in the DERS (u = −.40, z = −2.84, p < .01) and paranoia (u = −.94, z = −2.68, p = .01) from baseline to follow-up, and a decrease in negative affect from baseline to intervention (u = −.64, z = −2.41, p = .02).

Participant C

Visual analysis suggests modest changes between baseline and intervention phases in the expected direction, which are not maintained, for all but positive affect, which increases slightly at follow-up. Statistical analyses show a reduction in the DERS from baseline to intervention (u = −.68, z = −2.40, p = .02) followed by an increase from intervention to follow-up (u = .74, z = 2.91, p < .01), with no overall difference between baseline and follow-up (u = 0, z = 0, p = 1). Negative affect increases from baseline to intervention (u = .57, z = 2.03, p = .04), and positive affect increases from baseline to follow-up (u = .73, z = 2.26, p = .02).

Participant D

Visual analysis suggests modest improvement in the DERS and a reduction in negative affect across the three phases, and a slight increase in positive affect at intervention, which is not maintained at follow-up. Statistical analyses show reductions in the DERS from baseline to follow-up (u = −.67, z = −2.00, p = .05) and negative affect from intervention to follow-up (u = −.64, z = −2.26, p = .02). Positive affect reduced from baseline to follow-up (u = −.93, z = −2.79, p < .01).

Participant E

The clearest changes across phases are an increase in positive affect and a reduction in paranoia. This is consistent with statistical analyses which show an increase in positive affect (u = .71, z = 2.03, p = .04) and a decrease in paranoia (u = −.69, z = −1.95, p = .05) from baseline to follow-up.

Participant F

Visual analysis suggests improved emotion regulation (DERS and DTS), and reduced negative affect and paranoia across phases, although change in paranoia is not maintained at follow-up. The Tau-U results show a reduction in the DERS from baseline to follow-up (u = −1.00, z = −2.31, p = .02) and intervention to follow-up (u = −.96, z = −2.83, p < .01). Both negative (u = −.71, z = −2.09, p = .04) and positive affect reduce from baseline to intervention (u = −.79, z = −2.32, p = .02), as does paranoia (u = −.88, z = −3.17, p < .01).

Participant G

Visual analysis of the data suggests improved emotion regulation (DERS and DTS) from baseline to intervention. There is also a modest decrease in negative affect and increase in positive affect, and a reduction in paranoia across phases. Statistical analyses show reductions in the DERS (u = −.81, z = −2.45, p<.01), negative affect (u = −.91, z = −2.75, p < .01) and paranoia (u = −.97, z = −2.90, p < .01) between baseline and intervention.

Discussion

We used single case methodology to test whether emotion regulation skills rehearsal led to changes in affect and paranoia, for people who met criteria for schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Our results indicate that people with psychosis are able to learn and benefit from emotion regulation skills and, consistent with the hypothesis that negative affect increases likelihood of psychosis in vulnerable individuals due to poor emotion regulation (Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Hartmann, Köther and Moritz2015a; Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Sundag, Schlier and Karow2017), we found improved emotion regulation alongside reduced negative affect and paranoia for most participants.

All but one person showed improved emotion regulation, as assessed by the DERS. Five people showed reduced negative affect and five showed reduced paranoia. The pattern of changes is also revealing. Of the six who reported improved emotion regulation, four also showed reductions in both negative affect and paranoia, and one showed just a reduction in negative affect. Effects were not necessarily maintained over the follow-up phase, suggesting that the ability to regulate emotion is likely to require ongoing practice for longer-term benefits. ABA studies are designed to examine both the introduction and withdrawal of an intervention to determine the impact on outcome measures. Participants ceased skills rehearsal at the end of the intervention phase. It is now necessary to examine whether people are willing and able to practise these skills independently and over a longer period. Assessment of the feasibility and impact of longer-term practice would be a valuable next step.

Interestingly, improvement in emotion regulation was reflected in DERS but not DTS scores. We chose the DERS and DTS because these (i) assess capacity for, and function of emotion regulation (rather than focusing on specific skills, e.g. reappraisal and suppression), and (ii) are relatively brief, to minimise participant burden.

The DERS assesses non-acceptance of emotional responses, difficulties engaging in goal-directed behaviour, impulse control difficulties, lack of emotional awareness, limited access to emotion regulation strategies, and lack of emotional clarity. The DTS assesses the ability to tolerate, appraise, absorb and regulate distress. The difference in outcomes between the DERS and DTS was unexpected. The DTS focuses on beliefs about feeling distressed. The DERS incorporates a broader range of appraisals and responses, including awareness of emotions more generally. It may be that this broader emotional literacy incorporates but is not limited to appraisals in moments of distress. Further examination of the empirical differences between these measures is required given their conceptual overlap.

There was no clear pattern of change in positive affect. This is consistent with other studies suggesting that emotion regulation interventions may impact negative but not positive affect. For example, a DBT intervention for women with binge eating disorder resulted in improvements in binge eating and reductions in the extent to which anger prompted urges to eat, but no change in positive affect (Telch et al., Reference Telch, Agras and Linehan2001). Alternatively, the lack of change in positive affect may be because up to one-third of people with a diagnosis of schizophrenia report stable negative symptoms (cf. López-Díaz et al., Reference López-Díaz, Lara and Lahera2018).

Limitations of the study include the design, lack of stability over baselines, sample characteristics, our assessment of change, and provision of a small honorarium. While single case series methodology is well suited to initial examination of new treatment pathways (Morley, Reference Morley2018), and the sample size was within the typical range for this design (two to ten participants; Lobo et al., Reference Lobo, Moeyaert, Cunha and Babik2018), the generalizability of findings is limited (Tsang, Reference Tsang2014). Secondly, in single-case research, stability over the baseline phase is desirable (Gast, Reference Gast2010). However, this is often not possible in clinical studies, and may be less likely in people with psychosis given symptom fluctuation (Bak et al., Reference Bak, Drukker, Hasmi and van Os2016). Our participants did not evidence stable baselines. However, the gold-standard minimum of five baseline data points (Kratochwill et al., Reference Kratochwill, Hitchcock, Horner, Levin, Odom, Rindskopf and Shadish2010) was achieved for all but two participants (F and G, each with four data points for some measures). Additionally, we used the Tau-U test for change between phases which controls for any lack of central tendency within phases (including the baseline) (Wilcox and Keselman, Reference Wilcox and Keselman2003). Thirdly, our sample was exclusively Caucasian and European, although more typical of clinical populations in terms of severity and complexity of presentation (e.g. co-morbid diagnoses, recurrent hospital admissions). Fourthly, statistically significant change may not equate with clinically significant change (Leung, Reference Leung2001). Unfortunately, it was not possible to assess clinically significant change in the absence of clinical cut-offs for the measures used. In the absence of a measure of depression, it was also not possible to determine whether negative affect was associated with depressed mood in the current participants. Finally, the payment of a small honorarium for participants’ time and travel expenses may have acted as an incentive (although the majority of participants chose to donate this to charity).

While CBT certainly addresses emotion and aims to reduce distress, DBT utilises more experiential exercises designed to teach people how to regulate emotion directly, and in particular, how to down-regulate high levels of arousal. Our results suggest that people with psychosis can learn and benefit from these skills (cf. Lawlor, Reference Lawlor, Hepworth, Smallwood, Carter and Jolley2020). This contributes to the growing research examining the role of emotion awareness and regulation as causal pathways in psychosis (e.g. Ludwig et al., Reference Ludwig, Mehl, Schlier, Krkovic and Lincoln2020), and the impact of emotion-focused interventions (e.g. Favrod et al., Reference Favrod, Nguyen, Chaix, Pellet, Frobert, Fankhauser and Rexhaj2019).

In conclusion, difficulties identifying, accepting and modifying emotion may contribute to the maintenance of paranoia (Lincoln et al., Reference Lincoln, Hartmann, Köther and Moritz2015b), and yet we do not target affect directly in CBTp. This study suggests that people with psychosis are able to learn emotion regulation skills, and that this is associated with reductions in negative affect and paranoia. A larger scale study is now warranted, including longer-term practice, to determine whether emotion regulation skills rehearsal should be incorporated into psychological interventions for psychosis.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the seven people who took part in this study and agreed for their data to be summarised here.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statements

The authors have abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the BABCP and BPS. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the University of Southampton (Study ID: 31652) and NHS Research Ethics Committee (Study ID: 244247).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.