Introduction

CBT is on a voyage begun in the middle of the last century, and it is experiencing stormy winds – some driving it headward into a wider ocean and others buffeting it from all sides. This article describes seven pivotal (C)hallenges on the ‘seas’ ahead, and considers a future image of an effective and influential CBT.

The seven challenges

Clarity

CBT and its terminology require clarification. Poor clarity encourages miscommunication and misinterpretation. Successful systems within science and technology (e.g. astronomy, chemistry, anatomy, and engineering) use terms with precise meanings. CBT is not in such a certain state. The origins of terms within CBT are diverse, reflecting its integrative heritage. For example, Beck adopted the term “schema” from social and developmental psychology, terms like “belief”, “assumption” and “attitude” from common parlance, and more recent components such as “automaticity” and “selective attention” from cognitive psychology. The origins of CBT in its blending of cognitive therapy and behaviour therapy reveal not only theoretical ambiguities but a pot pouri of terms with diverse origins (Rachman, Reference Rachman, Clark and Fairburn1997). Since the mid-1990s, CBT appears to have changed again, into a family of allied therapies rather than as one commonly accepted system. For example, behaviour therapy, cognitive therapy, DBT, ACT and metacognitive therapy are all regarded as forms of CBT. Encouragingly, the EABCT is aiming to develop a common language of psychotherapy interventions (see EABCT, 2008). This initiative could be extended to psychological processes and other terms within CBT.

I searched the PubMed and PsychInfo databases for articles on the definition of CBT. There were none. Second, I accessed the BABCP and the ABCT for their working definitions of CBT. The BABCP provide a very useful document that explains the characteristics of CBT, definitions of the stepped levels of CBT provision and what kinds of competencies one would expect in a CBT therapist (Grazebrook and Garland, Reference Grazebrook and Garland2005). Finally, I contacted several CBT diploma courses in the UK and each referred me to the Cognitive Therapy Rating Scale (CTS; Young and Beck, Reference Young and Beck1980). As this is a measure of competency, I will return to it later.

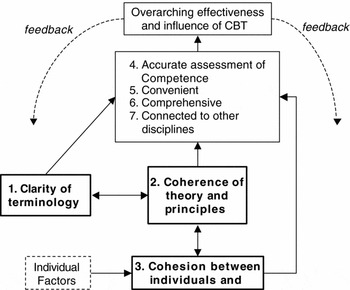

Several points were clear. First, there was a collection of key characteristics of CBT (see Figure 1). Among these qualities, there was no information on which of these criteria or which combination of these criteria would be either necessary or sufficient for a therapy to be called CBT, nor to differentiate it from other forms of therapy. Second, the characteristics were diverse and numerous. Perhaps having a large number of diverse properties indicates that CBT is suitably complex and multifaceted? However, it also makes defining and assessing CBT more difficult. Third, it appears that some of the characteristics of CBT are only loosely related to the underlying theories. For example, it is not clear from the original theory why CBT needs to be collaborative, nor why shifts in appraisal need to be carried out through guided discovery rather than direct instruction (Waddington, Reference Waddington2002). Fourth, the fact that CBT is an evidence-based psychotherapy was a key characteristic; however, while it is good practice to build an evidence base for a CBT intervention, this criterion is neither necessary nor sufficient to define CBT. Finally, there were some aspects of CBT that were presented as optional rather than definitive, such as helping the client to face feared situations, and how to learn to accept unpleasant emotions. It is likely that these components were included to reflect examples of practice from the different schools of CBT or for specific client groups.

Figure 1. A model of the proposed relationship between the different criteria/competencies of CBT provided in the literature

In summary, it appears that while the individuals and organizations responsible for training, assessing and disseminating CBT generally agree on its characteristics, there is limited clarity as to the features that would identify it and distinguish it from other therapies. More importantly, there is little research or serious discussion on how these criteria might be established. Yet, if the fundamental features and terminology of CBT can be clarified, then there is likely to be a positive impact on other features, such as its theoretical coherence, the assessment of competence, and clearer communication with other disciplines.

Coherence

For CBT to be a shared conceptual system, we would expect the terms to form common principles and be part of one theory. On the face of it, the level of coherence has been gradually reducing. Superficially, there is little in common between classic behavioural approaches, early cognitive therapy, and the promulgation of acronymic frameworks such as ICS, SPAARS, S-REF and RFT. Further approaches such as Motivational Interviewing and DBT draw upon an eclectic combination of theories. Each use partly shared and partly different terminology and appear to highlight different processes. To some therapists, eclecticism is a strength. However, to our colleagues and clients, the arena of CBT can appear as a confusing mixture of ideas. There is a clear onus for CBT clinicians, researchers and theorists to establish greater coherence. The alternative is for these different approaches to separate and diverge, which may be beneficial to each individually, but unlikely to further the cause of CBT as a common entity.

How might a greater theoretical coherence be attained? At the moment, the most prominent approach is Competition – survival of the fittest, with evidence, efficacy, citation and uptake as indices of fitness. An alternative approach is Collaboration – allied approaches combine within journal articles, and edited books (Hayes, Follette and Linehan, Reference Hayes, Follette and Linehan2004). They appear to agree about essential principles but their terminology and techniques can stay distinct. For example, while mindfulness is cultivated as a state of mind across a range of CBT therapies, this is achieved through differing means within ACT, DBT, metacognitive therapy and mindfulness-based CBT. An alterative route to coherence is the Coalescing of different approaches as they begin to borrow or integrate one another's terms, principles and techniques. For example, the rise of ACT has encouraged CBT therapists from other schools to talk about “acceptance of inner experience” within their existing approaches (see Hofmann and Asmundson, Reference Hofmann and Asmundson2008). A final pathway to coherence is the Creation of a theoretical framework that uses a new terminology but has the capacity to integrate the existing approaches; it may be considered “cognitive” or “behavioural” or of a different ilk entirely. Often, coherence is the goal of existing frameworks, but their attempts to integrate can be met with resistance by proponents of other models, leading back to the Competitive mode again. The best recommendation is perhaps that those involved in CBT consider the overlap between their approaches regardless of the superficial dissimilarities. This would be reflected in research studies that incorporate measures from multiple theoretical backgrounds, use statistical techniques to explore shared components, and target the mediational role of these processes in the maintenance of distress. Journals such as Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, and CBT conferences are critical in this respect.

Cohesion

The term “cohesion” refers to the links between individuals working within CBT. The degree of cohesion within CBT is less evident within published material than it is within the dialogue between individuals, both in the public arena of conferences and workshops, and the private arena of working relationships. Possible threats to cohesion occur down professional lines (psychiatrists; clinical psychologists; nurse therapists), levels of seniority (consultant; qualified; trainee; assistant), and points of practice (e.g. emphasis on behavioural versus cognitive change). My informal impression is that the key divisive topics actually relate to other examples of the Challenges for CBT – for example Clarity (“That's not even CBT he is practising!”) and Competence (“They don't have the formulation skills to practise CBT!”). In other words, the current issues concerning CBT, which CBT itself has not fully come to terms with, can form the basis of divisions within the profession. This cannot be fair – these are shared problems about CBT, rather than purely specific problems caused by any one subgroup. Therefore, if we manage the other challenges effectively, CBT might become more cohesive. Of course, internal politics are a normal experience; some amount of internal conflict suggests a constructive debate.

Competence

The focus on competence of CBT therapists is an important issue, in particular due to the drive for increasing the availability of CBT through initiatives such as the NICE Guidelines and the IAPT Scheme in the UK. The formal schemes for judging competence rely on specific criteria. However, this is clearly a challenge given the ambiguities of clarity and coherence described earlier – judging competence at CBT relies at least in part on a systematic definition of CBT and its principles, terminology and techniques.

The CTS is the most popular measure to assess competency. Owing to some difficulties in the breadth, application and inter-rater agreement for the CTS, three different revisions have been developed with no consensus on the most suitable (Kazantis, Reference Kazantis2003). There are two schools of thought in terms of whether therapist competence is a “trait” or “state” variable, and therefore whether competence should be rated once only, or on a regular basis. There appears to be no long-term prospective research to try to resolve this fundamental issue of whether competence can be lost once gained. Second, there is evidence that clients who are more suitable for CBT (e.g. can access thoughts, differentiate emotions and take responsibility for change), generate higher competence ratings of trainee therapists (James, Blackburn, Milne and Reichfelt, Reference James, Blackburn, Milne and Reichfelt2001). Thus, therapist competence appears to be a rating that is contextual to some degree rather than fully “trait-like”. On the positive side, evidence generally supports to view that competence improves during training (Milne, Baker, Blackburn, James and Reichelt, Reference Milne, Baker, Blackburn, James and Reichelt1999) and that competence is at least moderately related to patient outcome (Shaw et al., Reference Shaw, Elkin, Yamaguchi, Olmsted, Vallis, Dobson, Lowery, Sotsky, Watkins and Imber1999).

An intriguing development in CBT competence is a recent Department of Health document (IAPT Programme, 2007). The document was developed from a consultation with experts in CBT. It differentiates between several different kinds of competencies: generic; basic cognitive and behavioural therapy; specific CBT techniques; problem-specific and “metacompetencies”. Each category comprises between 8 and 13 elements, leading to a total of 51 competencies. They comprise the areas covered by the CTS, yet in addition some of them are highly specific (e.g. “OCD – Steketee/Kozac/Foa”; “applied relaxation and applied tension”). The document recommends against prioritizing some competencies over others because of the lack of evidence base for differentiating the components. Research studies to date tend to evaluate either components of a specific CBT model or the provision of the full therapy; few studies explore CBT with and without its various characteristics. Thus, the DoH document seems to conclude that all 51 competencies are necessary to deliver CBT. Yet, we do not know what proportion of currently accredited CBT therapists have these 51 competencies.

In order to try to consolidate the accounts of CBT and judgements of its competency, Figure 1 provides a heuristic model of the common factors across these accounts. The aim of this model is to simplify and integrate the multiple competences described in various sources rather than to provide a universal, theory-driven set of competences, which seems elusive at present. The reader is referred to at least two published theoretical models that are designed specifically to explain the development and assessment of competence in CBT (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006; Milne et al., Reference Milne, Claydon, Blackburn, James and Seikh2001).

Interestingly, no accreditation schemes establish competence by measuring the efficacy of treatment provided by a therapist. While there is tentative evidence that competence as a whole correlates with patients’ outcomes, this evidence is modest. Surely therefore, it is critical to establish not only that the therapist can competently deliver CBT, but that it also works effectively when used by this particular therapist, otherwise it would not be an adequate investment of a service user's time nor the finances of a health authority. It is impossible to guarantee that CBT delivered by one therapist to one client in one context is the same as that delivered by another therapist in another context. This suggests two things: first, that to establish the competence of a CBT therapist they would not only need to match specific criteria on one index client but also the efficacy of their therapy assessed across multiple client groups and contexts. Second, that there is no substitute for personal evaluation of one's own CBT practice – it may help an individual select the client group for whom they are most effective as therapists, and may help to offset any dichotomous assumptions that CBT will either work well or not work at all in a particular context. CBT therapists may therefore need to elicit regular feedback from their own clients, and be better equipped with the research skills to evaluate their practice (e.g. single case methodology). A more pertinent proviso to this approach is that clearly clients are responsible for their own recovery and will differ enormously in their levels of engagement and improvement. Thus, any personal evaluation of efficacy needs to be considered across multiple clients and a “no-blame”, constructive approach taken.

Convenience

Since the early days of CBT there have been drives to make it as accessible as possible in the form of self-help guides, providing alternative formats, and training a range of professions. Improving access to CBT in these ways has been shown to be effective. The issue of improving convenience interfaces with the other challenges – Clarity (“If we improve access by changing the format, is it still CBT?”); Coherence (“Should we be providing traditional CBT or new contemporary approaches? If so, which ones?”); Competence (“Are these individuals capable of delivering CBT in a group format? If not, might there be adverse effects on clients accessing other forms of CBT?”). This suggests that if the clarity, coherence and assessment of competence can be managed more effectively, then the concerns about the consequences of increasing its convenience would be reduced.

If future research were to be directed at distilling the key components of CBT that aid recovery within a coherent theory, then the extent to which each different formats of CBT enable these processes would be better understood. The very fact that self-help CBT works effectively prompts interesting theoretical questions – is a collaborative therapeutic relationship therefore not necessary, or is the interpersonal style in which the self-help material is written actually very important? Might CBT be more efficient if key elements are controlled by the client, such as the frequency and number of sessions (Carey, Reference Carey2005)? It is easy to consider the increased accessibility of CBT as a “watering down” process, but it also has the capacity to distil and test some of the key mediators of change.

Comprehensiveness

It is apparent that CBT has spread its influence broadly, across a wide range of psychological disorders. Therefore, one might conclude that comprehensiveness is not a challenge. However, within a service context, CBT is not comprehensive. There are many conditions that are poorly served often owing to training limitations, such as CBT for bipolar disorder and personality disorders. CBT is not comprehensive in a geographic sense, with many areas within countries that provide CBT being poorly served, and wide regions of the developing world have near-zero availability. In addition, in some localities the availability of CBT is limited by attitudinal factors – those individuals who are in a position to grant access to publicly available therapy can be unwilling to refer certain clients. They may for example believe that CBT is not suitable for certain disorders, or for people of a certain level of education. If CBT is going to be truly comprehensive it needs to address these barriers created by training limitations, geography and resistant attitudes.

Resistant attitudes towards CBT may be partly aided by the improved assessment of competence because those individuals practising CBT would be more actively involved in refining their practice and monitoring their clinical outcomes within their service. A further method would be to improve Connectivity with the non-CBT community. Further, if the terminology and theory of CBT can be distilled in a coherent, efficient manner to isolate the most active ingredients, then we might expect improved training efficiency and wider dissemination to follow. This is one of the drivers behind a “transdiagnostic” approach to CBT (Harvey, Watkins, Mansell and Shafran, Reference Harvey, Watkins, Mansell and Shafran2004) which, based on a comprehensive review of processsing biases across psychological disorders, advocates the development of CBT that focuses on treating these core maintenance processes irrespective of diagnosis, but within the context of the individual's personal concerns. The potential increase in comprehensiveness of CBT generated by this approach would be huge because of the increase in efficiency it implies. However, one major hurdle for such an approach is that any new “transdiagnostic” therapy needs to develop within a coherent theoretical model.

We may also need to consider whether truly comprehensive CBT is a worthwhile ideal. For example, there remains a real question of which individuals are prioritized to receive CBT considering the evidence of effectiveness in different “groups”. There are large-scale decisions based on this evidence (e.g. IAPT). If the availability of CBT does need to be restricted, might it be better based upon psychological predictors of efficacy rather than on diagnostic groupings?

Connectivity

It is a great advantage of CBT that it interests diverse groups of health professionals. Its focus on establishing an evidence-base has helped it to be recommended by organizations including service user groups, Royal Colleges, and NICE. However, it is clear that there are individuals or groups who are less open to CBT, including some schools of psychotherapy and certain proponents of biological psychiatry. As mentioned earlier, some of these conflicts are maintained by misunderstandings of CBT that are partly a function of the assumptions of those critics, but they also partly result from the ambiguities within CBT and the biases or limitations in how it has been disseminated. Thus, while we cannot always prevent overt misinterpretations of CBT, we might be able to mitigate against them by communicating its principles in a lucid manner (e.g. Veale, Reference Veale2008).

In addition to direct oppositions to CBT, there are also more subtle conceptual boundaries to integrating CBT with other disciplines. For example, how might we explain what is a “belief” or a “schema” to someone who uses a medical or life sciences model? If some of our beliefs are culturally influenced, how does this work? There are already some direct attempts to improve the connectivity of CBT with other disciplines (e.g. Gilbert, Reference Gilbert2004; Mansell, Reference Mansell2005). Ideally, any clear, coherent framework that guides the future direction of CBT needs to not only be accessible to training and dissemination of the practice of CBT, but also needs to easily relate its terminology to other disciplines such as medicine, biology and sociology. Thus, the terminology may need to be revised. This may sound like a tall order, but it may be a worthwhile means to improve the acceptance and use of CBT.

Conclusions

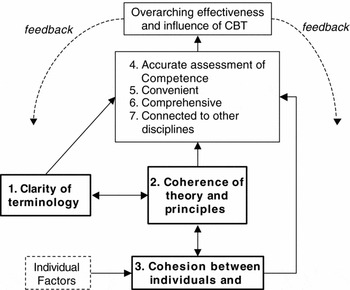

Figure 2 provides a summary of the seven C's over which CBT must set sail, and it provides a potential model of their relationship. In a similar way to Salkovskis (Reference Salkovskis2002), it proposes that theory and scientific evaluation are at the heart of developments in CBT and that there is a reciprocal relationship between science and practice. More specifically, this model proposes that establishing clarity of definitions of CBT and its key components and integrating these within a single coherent theoretical framework are critical.

Figure 2. A model of the proposed relationship between Seven Challenges for CBT and how they can be tackled to enhance the effectiveness and influence of CBT as a whole

This article has attempted to clarify the challenges, explored their relationship with one another, and proposed a process for rising to them. However, the content (the exact terms and theory) is open-ended and awaits future developments. The main thrust of this article is summarised in one sentence - if we can get a better idea of what CBT is and how it works then we can all agree on ways to judge how well it works, in the different ways it is provided, for as many people as possible, and then tell other people about it. To make these changes, the key figures in CBT need to talk to one another and explore common ground. Where discrepancies occur, focused research can provide clarification. If we can maintain the shared goal of enhancing CBT's impact, then there is every reason to believe there will be an eventual increase in its clarity and coherence and the positive consequences that this would entail.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.