Introduction

Scrupulosity is characterized by obsessional fear of thinking or behaving immorally or against one's religious beliefs (e.g. Greenberg, Reference Greenberg1984; Greenberg and Huppert, Reference Greenberg and Huppert2010; Greenberg and Shefler, Reference Greenberg and Shefler2002). Common religious obsessions include intrusive blasphemous images, fears that one has committed a sin or performed a religious custom incorrectly, and fears of punishment from a higher power. Associated compulsions involve excessively repeating religious practices (e.g. prayer, confession) and seeking reassurance from religious authorities. Religion is the fifth most common obsessional theme among individuals with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD; Foa and Kozak, Reference Foa and Kozak1995), affecting one-quarter to one-third of all people with this diagnosis (Antony et al., Reference Antony, Downie, Swinson, Swinson, Antony, Rachman and Richter1998; Mataix-Cols et al., Reference Mataix-Cols, Marks, Greist, Kobak and Baer2002). Moreover, this presentation of OCD is associated with poorer insight relative to other types of obsessions and compulsions (Tolin et al., Reference Tolin, Abramowitz, Kozak and Foa2001). Scrupulous individuals also experience impaired social and occupational functioning, as well as depression, guilt and anxiety (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Abramowitz, Whiteside and Deacon2006; Siev et al., Reference Siev, Baer and Minichiello2011a,Reference Siev, Steketee, Fama and Wilhelmb). Evidence suggests that the presence of scrupulosity predicts poorer outcomes in OCD treatment, which may be attributed to limited knowledge among clinicians about this symptom presentation, as well as inadvertent reinforcement of subtle rituals by members of religious communities (Huppert and Siev, Reference Huppert and Siev2010).

Findings from numerous structural analyses of OCD symptoms (for a review, see McKay et al., Reference McKay, Abramowitz, Calamari, Kyrios, Radomsky and Sookman2004) converge to suggest that the thematic heterogeneity of obsessions and compulsions can be distilled into four dimensions including: (a) contamination obsessions and de-contamination rituals; (b) obsessions about responsibility for harm or mistakes and checking rituals; (c) unacceptable obsessional thoughts and mental neutralizing and reassurance-seeking rituals; and (d) incompleteness obsessions and order/symmetry rituals. Although religious themes may appear in any of these symptom dimensions, research indicates that scrupulosity is most prominent among the unacceptable thoughts dimension in both clinical and non-clinical samples (e.g. Kaviani et al., Reference Kaviani, Eskandari and Ebrahimi Ghavam2015; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Abramowitz, Whiteside and Deacon2006; Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Abramowitz, Williams, Connolly and Lohr2007). This is in concert with studies showing that religious obsessions share numerous phenomenological features with obsessions about ‘taboo’ topics, such as sex and violence (e.g. Lee and Kwon, Reference Lee and Kwon2003; McKay et al., Reference McKay, Abramowitz, Calamari, Kyrios, Radomsky and Sookman2004; for a different perspective, see Siev et al., Reference Siev, Baer and Minichiello2011a,Reference Siev, Steketee, Fama and Wilhelmb).

The relationship between scrupulosity and unacceptable thoughts can be further understood in the context of cognitive behavioral models of obsessions. Rachman (Reference Rachman1997, Reference Rachman1998), for example, proposed that such obsessions develop when normally occurring upsetting thoughts are misinterpreted as unacceptable, immoral and personally significant (e.g. ‘thinking about something terrible is the moral equivalent of doing something terrible’). This cognitive style is known as thought-action fusion (TAF; Shafran et al., Reference Shafran, Thordarson and Rachman1996). He suggested that religion could foster TAF, noting that ‘people who are taught, or learn, that all their value-laden thoughts are of significance will be more prone to obsessions – as in particular types of religious beliefs and instructions’ (p. 798). Indeed, there are abundant examples of religious doctrine and scripture that appear consistent with TAF, such as the 10th commandment from the Bible, which forbids one from coveting (i.e. wishing to have) another person's property, and the Sermon on the Mount, in which Jesus warns that ‘everyone who looks on a woman to lust for her has committed adultery already in his heart’ (Matthew 5:27–28).

In an experimental study to examine the relationship between religious affiliation and TAF, Berman et al. (Reference Berman, Abramowitz, Pardue and Wheaton2010) found that highly religious participants believed that writing and thinking about negative events was more morally wrong and more likely to increase the event's likelihood, compared with non-religious participants. Moreover, Siev et al. (Reference Siev, Chambless and Huppert2010) found that both Catholic and Protestant individuals endorsed higher levels of moral TAF than Jewish individuals independent of OCD symptoms, and that moral TAF predicted OCD symptoms only in Jewish individuals. These findings suggest that TAF is only a marker of pathology when such beliefs are not culturally normative, underscoring the importance of religious affiliation in the assessment of OCD symptoms.

Abramowitz and Jacoby (Reference Abramowitz and Jacoby2014), drawing on the work of Rachman, hypothesized that religious affiliation influences the presence and form of scrupulous obsessions and compulsions. Indeed, Protestant Christians score higher on a measure of scrupulosity (i.e. Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity) than Catholics, Jews and those without a religious affiliation (e.g. Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin and Cahill2002; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Abramowitz, Whiteside and Deacon2006). This trend is consistent with the finding that Protestant individuals show a greater tendency to believe that negative thoughts are morally relevant compared with Jewish (Cohen and Rozin, Reference Cohen and Rozin2001) and Catholic individuals (Rassin and Koster, Reference Rassin and Koster2003). Purity of thought, and the equivalence of thoughts and behaviours, are also features of Catholic teachings, so one might expect scrupulosity to present primarily in the form of unacceptable obsessional (i.e. sinful) thoughts among Catholic individuals. Alternatively, given the practice of confessing sin, Catholic individuals may be especially likely to consider the possibility of wronging others, which may be associated with OCD symptoms regarding responsibility for harm.

Comparatively, Judaism and Islam are considered ritualistic religions with a focus on adhering to behavioural codes of conduct rather than maintaining particular beliefs (Okasha, Reference Okasha2004; Siev and Cohen, Reference Siev and Cohen2007). Thus, among individuals identifying as Jewish or Muslim, obsessions concerning purity and contamination, fears of not having fulfilled religious customs correctly, and checking rituals may be more common than obsessional fears that one has sinned by having improper thoughts (Huppert et al., Reference Huppert, Siev and Kushner2007; Inozu et al., Reference Inozu, Clark and Karanci2012). Greenberg and Shefler (Reference Greenberg and Shefler2002), however, found that of 28 ultra-orthodox Jewish individuals with OCD, 26 had religious symptoms, and on average, each individual had three times more religious symptoms than non-religious symptoms. This suggests that rather than scrupulosity being less common or less severe among Jews compared with Christians, scrupulosity may manifest differently among Jewish individuals. Thus, more research is necessary to examine how religious affiliation, scrupulosity and OCD symptoms are inter-related. Clarifying these associations would enhance the assessment and treatment of scrupulosity, which is one of the more difficult presentations of OCD to treat.

We therefore aimed to expand the existing literature by examining the relationships between religious affiliation, scrupulosity and OCD symptoms in a large treatment-seeking sample of patients with a primary diagnosis of OCD. In particular, we examined the relationship between religious affiliation and OCD symptoms, the association between religious affiliation and scrupulosity, and the associations between scrupulosity and OCD symptom severity across religious affiliations. We hypothesized that (a) symptom severity would not differ across religious affiliations; (b) patients with any religious affiliation would endorse greater scrupulosity than those who did not report a religious affiliation; (c) scrupulosity would be associated with both global and dimensional OCD symptoms, with the strongest relationship between scrupulosity and the unacceptable thoughts dimension; and (d) the magnitude of the relationships between scrupulosity and OCD symptoms would vary across religious affiliations.

Method

Participants

Participants included 180 adults (42.2% female; n = 76) with a primary diagnosis of OCD seeking treatment at residential, partial hospital and intensive outpatient programs within the multi-site Rogers Memorial Hospital network of OCD-specific treatment programs. The majority of patients (68%; n = 122) were given a secondary diagnosis during an in-person semi-structured diagnostic evaluation with a psychiatrist. Mood disorders were the most common secondary diagnosis (32.8%, n = 59), followed by anxiety disorders (22.8%, n = 41). The sample's mean age was 30.3 years (SD = 12.5; range = 18–68) and the sample was 87.2% (n = 157) White, 1.7% (n = 3) Asian, and 1.7% (n = 3) Black or African American. Regarding religious affiliation, 37.2% (n = 67) of the sample identified as Catholic, 26.7% (n = 48) identified as Protestant, 25.6% (n = 46) identified as having no religion, and 10.6% (n = 19) identified as Jewish.

Measures

In addition to providing demographic information (including current religious affiliation), participants completed the following self-report measures of scrupulosity and OCD symptom severity.

Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity (PIOS; Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin and Cahill2002)

The 19-item self-report PIOS assesses scrupulosity in the context of OCD (i.e. religious obsessions). The PIOS consists of two subscales: Fear of Sin (e.g. I am afraid of having sexual thoughts) and Fear of God (e.g. I worry that God is upset with me), which have been supported by exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (Olatunji et al., Reference Olatunji, Abramowitz, Williams, Connolly and Lohr2007). Items are scored on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (constantly). Participants also selected current religious affiliation from a list that included Catholic, Protestant, Jewish and No Religion. The PIOS has shown adequate psychometric properties in non-clinical samples (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin and Cahill2002) and demonstrated good internal consistency in a clinical sample (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Abramowitz, Whiteside and Deacon2006). More recent factor analyses suggest that a bifactor model is the most suitable solution for the PIOS, with revised subscales that have shown moderate–good concurrent validity: Fear of God and Fear of Immorality (Huppert and Fradkin, Reference Huppert and Fradkin2016). However, in this study, PIOS scores discriminated poorly between patients with scrupulous obsessions and patients with OCD and other repugnant obsessions, and the measure was more suitable for discriminating scrupulous obsessions in Christian patients than other religious groups (i.e. Jews, non-religious patients). The PIOS demonstrated excellent reliability (Cronbach's alpha = .96) in the present sample.

Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale-Self Report (Y-BOCS-SR; Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Bogart1996)

The Y-BOCS-SR is a global OCD measure that includes a symptom checklist and a 10-item severity scale assessing obsessions and compulsions that are each scored based on (a) time occupied by symptoms, (b) interference, (c) distress, (d) resistance, and (e) degree of control. Each item is rated on a scale from 0 (no symptoms) to 4 (extreme), yielding total severity scores that range from 0 to 40. The Y-BOCS-SR has acceptable internal consistency (α = .78) with OCD samples and acceptable test–retest reliability (r = .79) over a 1-week interval (Steketee et al., Reference Steketee, Frost and Bogart1996). As can be seen in Table 1, the measure demonstrated good reliability in the present sample (α = .86).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and internal consistency coefficients

PIOS, Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity; Y-BOCS-SR, Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale Self-Report; DOCS, Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale.

Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (DOCS; Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Deacon, Olatunji, Wheaton, Berman and Losardo2010)

The 20-item self-report DOCS assesses the severity of four empirically validated OCD symptom dimensions: (a) contamination, (b) responsibility for harm and mistakes, (c) symmetry/ordering, and (d) unacceptable thoughts. Within each symptom dimension, five items (rated 0 to 4; anchors change across items) assess the following parameters of severity: (a) time occupied by obsessions and rituals, (b) avoidance behaviour, (c) associated distress, (d) functional interference, and (e) difficulty disregarding the obsessions and refraining from the compulsions. The DOCS subscales have shown excellent reliability in clinical samples and good convergent validity with other measures of OCD symptoms (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Deacon, Olatunji, Wheaton, Berman and Losardo2010). The DOCS subscales demonstrated excellent reliability in the present sample (α = .94–.96).

Procedure

Upon admission, each patient completed the Y-BOCS-SR and an in-person evaluation with a psychiatrist to confirm the diagnosis of OCD. Individuals included in the present study were those age 18 and over with a primary diagnosis of OCD. Each participant also completed the PIOS and DOCS prior to beginning treatment. As part of the admission process, patients provided consent (either written or online) for the study measures to be used for both clinical and research purposes. The consent procedures and study measures were approved by both the Human Subjects Committee and the Rogers Center for Research and Training.

Statistical analyses

To evaluate our first hypothesis that OCD symptom severity would not differ across religious affiliations, we conducted five one-way ANOVAs that examined differences in Y-BOCS-SR total and DOCS subscale scores across religious affiliations. To evaluate our second hypothesis that individuals identifying with a religion would endorse greater scrupulosity than those who did not identify as religious, we conducted a one-way ANOVA to examine differences in PIOS scores across religious affiliations. To evaluate our third hypothesis that scrupulosity would be associated with OCD symptoms with the strongest relationship between scrupulosity and unacceptable thoughts, we computed Pearson correlation coefficients to examine the relationships between the PIOS, Y-BOCS-SR and DOCS in the full sample and within each religious group. The strength of the correlations were compared using the calculation for the test of the difference between two dependent correlations with one variable in common (Lee and Preacher, Reference Lee and Preacher2013; Steiger, Reference Steiger1980). Finally, to examine our fourth hypothesis testing the strength of the relationship between scrupulosity and OCD symptoms in different religious groups, we conducted a regression-based moderation analysis using the PROCESS macro for SPSS (Hayes, Reference Hayes2013).Footnote 1

Results

Descriptive statistics and internal consistency

Preliminary analyses indicated that the two PIOS subscales were strongly correlated, r (178) = .80, p < .001, and that both the Fear of God and Fear of Sin subscales were correlated strongly with the PIOS total score (r = .92 and .97, p < .001). In addition, the Y-BOCS-SR obsessions and compulsions subscales were strongly correlated, r (178) = .49, p < .001, and both Y-BOCS-SR subscales were strongly correlated with the total score (r = .86 and .87, p < .001). Therefore, as in most research using these measures, we used the PIOS and Y-BOCS-SR total scores in all analyses reported below. The means and standard deviations for all study measures are given in Table 1.

Differences in OCD symptoms by religious affiliation

Five separate one-way ANOVAs revealed no significant differences between religious affiliations on the Y-BOCS-SR total score or any DOCS subscale (all p > .05).

Differences in scrupulosity by religious affiliation

A one-way ANOVA revealed significant differences in PIOS scores among religious affiliations, F (3,176) = 5.42, p = .001, ηp2 = .09. Tukey's post hoc tests revealed that individuals who identified as Catholic had higher average PIOS scores than those who identified as Jewish (p = .010, Hedges’ g = .83) or as having no religion (p = .008, Hedges’ g = .64). However, on average, PIOS scores of Jewish participants were not significantly different from PIOS scores of Protestant participants (p = .09, Hedges’ g = .60) or participants with no religion (p = .92, Hedges’ g = .19). Moreover, PIOS scores of Protestant participants were not significantly different from those of Catholic participants (p = .86, Hedges’ g = .14) or participants with no religion (p = .12, Hedges’ g = .45). Mean PIOS scores across religious affiliations are shown in Table 2.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for PIOS score by religious affiliation

Superscripts denote statistically significant differences (p < .01). PIOS, Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity.

Relationship between scrupulosity and OCD symptom severity

Full sample

In the full study sample, the PIOS was significantly correlated with the Y-BOCS-SR total score (p < .05) as well as with scores on each DOCS subscale (all p < .05). As predicted, the relationship between the PIOS and the DOCS-Unacceptable Thoughts dimension was significantly stronger than that between the PIOS and symptom severity on the other three dimensions, based on the test of the difference between dependent correlations (all p < .001). The results of this analysis are given in Table 3.

Table 3. Pearson correlation coefficients between the PIOS and measures of OCD symptom severity by religious affiliation

*p < .05; **p < .01, ***p < .001. PIOS, Penn Inventory of Scrupulosity; DOCS, Dimensional Obsessive-Compulsive Scale; Y-BOCS-SR, Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale-Self Report.

Differences across religious groups

When each religious affiliation was examined individually, correlations between the PIOS and Y-BOCS-SR did not reach significance. However, significant relationships were found between specific DOCS subscales and religious affiliations. Among individuals who identified as Protestant, the PIOS was significantly correlated with DOCS-Unacceptable Thoughts. For individuals who identified as Catholic, the PIOS was also significantly correlated with DOCS-Unacceptable Thoughts, as well as with DOCS-Responsibility for Harm. For individuals who identified as Jewish, the PIOS was significantly correlated with DOCS-Unacceptable Thoughts, DOCS-Responsibility for Harm, and DOCS-Contamination. For individuals who did not identify with any religion, the PIOS was only significantly correlated with DOCS-Unacceptable Thoughts. The results of these analyses are given in Table 3.

Religious affiliation moderating the relationship between scrupulosity and OCD symptom severity

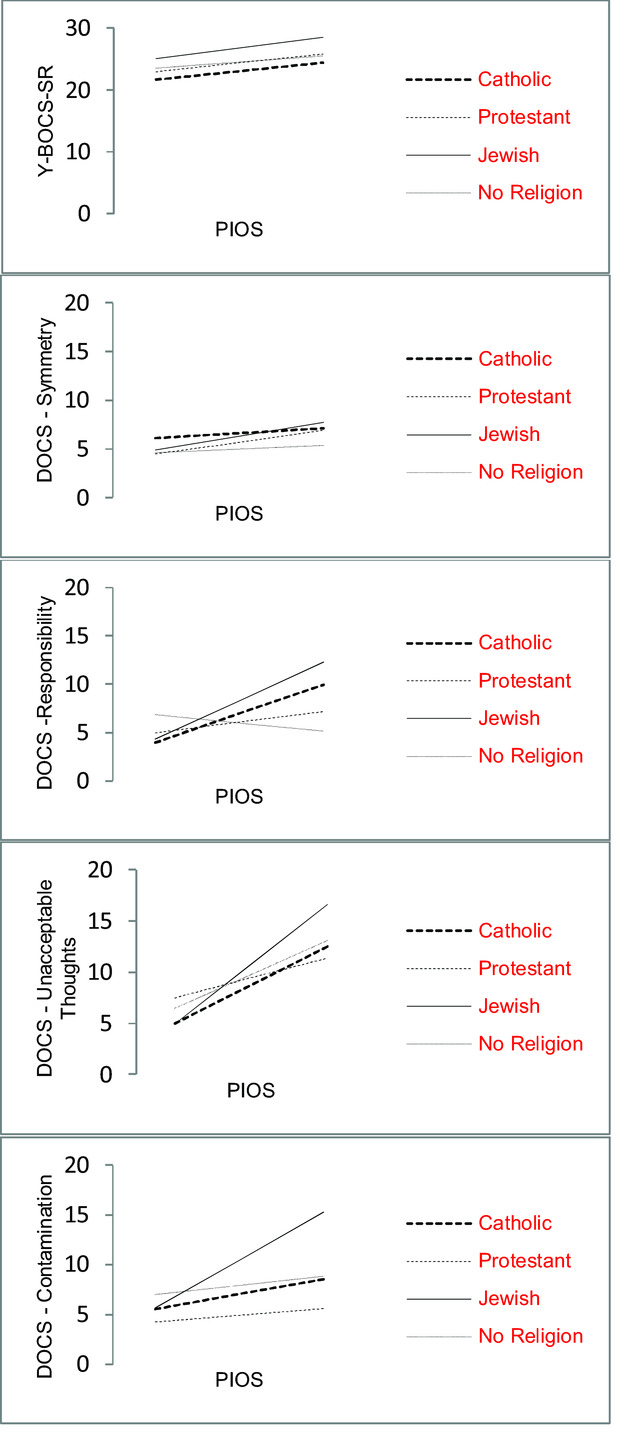

Religious affiliation did not significantly moderate the relationship between PIOS and Y-BOCS-SR scores (p > .05), nor that between PIOS and DOCS-Symmetry scores (p > .05). However, moderation analyses revealed that the relationship between the PIOS and DOCS-Responsibility scores was significantly different between individuals who identified as Jewish (B = .20) and those who indicated having no religion (B = –.05; p < .05), and between those who identified as Catholic (B = .15) and those who did not identify with any religion (B = –.05; p < .01). Additionally, the relationship between PIOS and DOCS-Contamination scores was significantly different between individuals who identified as Protestant (B = .03) and those who identified as Jewish (B = .24, p < .05). Finally, the relationship between PIOS and DOCS-Unacceptable Thoughts scores was significantly different between individuals who identified as Protestant (B = .10) and individuals who identified as Jewish (B = .30; p < .05). Results are given in Fig. 1.

Figure 1. Religious affiliation moderating the relationship between scrupulosity and OCD symptom severity. The y-axis varies across graphs. PIOS scores range from 0.0 to 76.0.

Discussion

Scrupulosity is a common yet understudied presentation of OCD that is associated with attenuated treatment outcomes. Existing research suggests that scrupulosity is related to both religious affiliation and OCD symptom severity, yet gaps in the literature exist. In the present investigation, we sought to elucidate the nature of these associations using a large sample of treatment-seeking adults with a primary diagnosis of OCD. We derived our hypotheses from a conceptual model of scrupulosity (Abramowitz and Jacoby, Reference Abramowitz and Jacoby2014) that draws on cognitive behavioural formulations of OCD (e.g. Rachman, Reference Rachman1997, Reference Rachman1998).

Our first hypothesis was supported, in that we found no differences across religious affiliation with respect to global OCD symptom severity or the severity of any particular OCD symptom dimension. Consistent with our second hypothesis, however, differences in the degree of scrupulosity emerged across religious affiliations. Although our data are cross-sectional, these findings are consistent with the notion advanced by Huppert and Siev (Reference Huppert and Siev2010) that religious identity does not influence the overall severity of OCD, yet it may inform the manifestation (i.e. presentation) of OCD symptoms. In our sample, patients with OCD who identified as Catholic reported greater levels of scrupulosity than those who identified as Jewish and as not having a religious affiliation, but levels of scrupulosity were not significantly different between those who identified as Catholic and those who identified as Protestant. The non-significant difference in levels of scrupulosity between Catholic and Protestant individuals diverges from findings suggesting that Protestant individuals report greater levels of scrupulosity than Catholic individuals (e.g. Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin and Cahill2002; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Abramowitz, Whiteside and Deacon2006; Rassin and Koster, Reference Rassin and Koster2003). Our results parallel findings from previous studies showing that individuals identifying as Jewish score lower on the PIOS relative to Christians (e.g. Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin and Cahill2002; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Abramowitz, Whiteside and Deacon2006). One explanation for this finding is that scrupulosity is a less prevalent manifestation of OCD among patients identifying as Jewish relative to Christian. Yet, as suggested by Greenberg and Huppert (Reference Greenberg and Huppert2010), it is also possible that the PIOS is a less sensitive measure of scrupulosity among Jewish individuals, such that Jews experience scrupulosity in ways that are not tapped by the PIOS. Moreover, moral TAF correlates strongly with PIOS scores (e.g. Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Abramowitz, Whiteside and Deacon2006), which may help account for differences on the PIOS between Christian and Jewish individuals because Christians score significantly higher than Jews on measures of TAF (Siev and Cohen, Reference Siev and Cohen2007). Parallel to elevated TAF among Christians relative to Jews (Siev et al., Reference Siev, Chambless and Huppert2010), higher PIOS scores among Christian individuals in the present study may indicate that they hold culturally normative beliefs that are captured by the measure but are not associated with more severe pathology. Finally, some individuals without a current religion may have identified with a religion in the past, and therefore endorse scrupulous beliefs. Such considerations raise important questions for future research.

Our correlational analyses supported our third hypothesis that scrupulosity is most strongly associated with unacceptable sexual, violent or blasphemous obsessional thoughts and neutralizing rituals. This was the case among patients who both did and did not report a religious affiliation. Although the present study does not allow for causal inferences, such a finding is consistent with the idea that personal beliefs and values inherent in Judeo-Christian doctrine foster ideas that one's thoughts are significant and meaningful (e.g. Wheaton et al., Reference Wheaton, Abramowitz, Berman, Riemann and Hale2010). Accordingly, when thoughts about taboo topics come to mind, scrupulous individuals might make misinterpretations in ways that lead to obsessional preoccupation and efforts to resist, avoid, or ‘put them right’. The differences in the strength of the relationship between scrupulosity and symptom severity across dimensions also underscore the heterogeneity of OCD symptoms and the importance of a dimensional assessment and conceptualization of OCD.

The positive relationship we found between scrupulosity and unacceptable thoughts among individuals who did not identify with a particular religion is consistent with the idea that religious identity is not the only factor that contributes to scrupulous beliefs (e.g. Salkovskis et al., Reference Salkovskis, Shafran, Rachman and Freeston1999). Siev and colleagues (Reference Siev, Baer and Minichiello2011a,Reference Siev, Steketee, Fama and Wilhelmb) referred to the phenomenon of ‘secular scrupulosity’ in which the person has a heightened or rigid sense of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ but does not identify with a particular religion. Indeed, Salkovskis and colleagues proposed multiple pathways to becoming highly sensitive to unwanted thoughts, such as experiences in which thoughts appeared to contribute to misfortune. Although our data do not speak to this possibility, individuals who did not report identifying with a religion at the time of assessment may nevertheless have identified with a religion in the past, such that their scrupulous symptoms may be distally related to previous religious experiences. Alternatively, these individuals may have developed a rigid moral code outside the context of religion.

We were surprised, however, to find that almost one in five scrupulous participants reported no religious affiliation, which might reflect those who have a heightened or rigid sense of right and wrong (intrinsic morality) but do not identify with a particular religion. This ‘‘secular scrupulosity’’ is a form of scrupulosity that clinicians encounter less frequently and one that merits further research. Another possibility is that participants who reported no religious affiliation were raised affiliated but abandoned their religion. In support of our fourth hypothesis, the magnitude of the relationship between scrupulosity and global and dimensional OCD symptom severity differed across religious affiliations. This finding suggests that the presentation of OCD symptoms differ based on an individual's religious background. For example, the difference in the relationship between the PIOS and DOCS-Responsibility scores between individuals who identified as Catholic and those who indicated having no religion may be explained by the Catholic custom of alleviating guilt through prayer and confession (Murray-Swank, McConnell, and Pargament, Reference Murray-Swank, McConnell and Pargament2007). Clinical observations suggest that in an effort to reduce obsessional doubt, scrupulous individuals with a Catholic background often engage in excessive prayer, confession, and reassurance seeking from religious authorities.

Additionally, the difference in the relationship between PIOS and DOCS-Contamination between individuals who identified as Protestant and those who identified as Jewish is consistent with the focus on behavioural codes in Judaism, such as dietary laws and other laws regarding purity (e.g. hand washing, cleaning). The Torah, for example, contains regulations about purity and cleanliness (e.g. Leviticus 15:10–12 New International Version), as well as the details of how cleaning is to be conducted in various situations (e.g. Leviticus 15:13–14 New International Version) or as part of religious ceremonies. Clinical observations indicate that many (particularly Orthodox) Jews with scrupulosity compulsively repeat these customs to allay concerns about impurity and ensure that such rituals have been carried out as proscribed in the Torah. Among Jewish individuals, the strong relationship between scrupulosity and OCD symptoms may be explained by evidence that, on average, Jewish individuals do not endorse PIOS items as strongly as Christian individuals (Abramowitz et al., Reference Abramowitz, Huppert, Cohen, Tolin and Cahill2002), so when Jews do report high PIOS scores they are especially strong indicators of pathology. This parallels the conclusions of Siev and colleagues (Reference Siev, Chambless and Huppert2010) about TAF that when cognitions deviate from religious norms they are more closely related to OCD symptomology.

The findings from this study have implications for assessment, case conceptualization and intervention. First, for patients who present with OCD symptoms related to religion, clinicians should assess for the presence of obsessions about taboo topics such as blasphemy, sex and violence, and rituals that function to neutralize, ‘put right’, or otherwise suppress such thoughts (e.g. prayer), and consider these symptoms within the context of the individual's religious affiliation. Given that that the relationship between scrupulosity and OCD symptoms was associated with both religious affiliation and OCD symptom presentation, clinicians should consider the intersection of these patient characteristics. For example, individuals with high levels of scrupulosity who identify as Catholic may be at heightened risk for particularly severe obsessions and compulsions related to responsibility for harm, whereas Jewish individuals with high levels of scrupulosity may have these symptoms as well as contamination symptoms.

Moreover, assessment should include the misinterpretation of the presence and meaning of obsessional thoughts as morally unacceptable and equivalent to committing sinful behaviour, specifically identifying beliefs that deviate from norms of the individual's religious community. When working with patients identifying as Catholic, one might also screen for obsessions regarding inflated responsibility for committing or failing to prevent sin. Among Jewish patients, it is important to assess for obsessions and compulsions related to cleanliness and purity both in a practical (e.g. keeping the dietary laws) and spiritual sense. However, given diverse religious beliefs and practices within religious groups, clinicians must be mindful of individual differences when assessing religion-based obsessions and compulsions. Given our findings regarding a relationship between scrupulosity and unacceptable thoughts among individuals who did not report a religious affiliation, it would also be important to assess for TAF and moral rigidity, as one's upbringing and cognitive style may affect longstanding beliefs about the relationship between thoughts and actions.

Although cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) using exposure and response prevention (ERP) can be highly effective for OCD (Kozak and Coles, Reference Kozak and Coles2005), many patients with scrupulosity have difficulty with this approach when exposure tasks are perceived as conflicting with religious doctrine. An overall goal of targeting scrupulosity is to differentiate normative religious practices and beliefs from OCD symptoms to help patients engage with religion in beneficial ways. Accordingly, clinicians might educate themselves about the tenets of the patient's religion so that the selection of exposure items is both therapeutic and sensitive to the religious affiliation of the patient. Given our findings with patients who did not report a religious affiliation, it is important that clinicians consider scrupulosity in such individuals as well.

The current study is not without limitations. First, as noted previously, one limitation is that the PIOS – which is currently the only measure of scrupulosity – may be more valid among members of some religions than others (Huppert and Fradkin, Reference Huppert and Fradkin2016). The development of additional religion-specific and culturally sensitive measures of scrupulosity will improve research, assessment and treatment of this phenomenon. Such research could also better address the question of whether religious obsessions belong in the same dimensional category as obsessions about sex and violence, or whether the seeming co-occurrence of these obsessions is merely an artifact of current conceptualizations of OCD. Second, as noted earlier, the cross-sectional design of this study precludes conclusions about causality. Longitudinal research is necessary to examine aetiological hypotheses, as the direction of the causal arrow remains unknown. Indeed, religious affiliation and experiences may lead to the development of scrupulosity, yet pre-existing scrupulosity may also motivate individuals to affiliate with and seek comfort in the religious structure of rules, conduct and duty.

A third limitation of this study is that its results are based solely on self-report measures, which are subject to bias and can artificially inflate relationships between variables. Multi-modal measurement would improve future research, as would the inclusion of additional measures that are associated with scrupulosity. For example, as noted previously, a measure of TAF would improve our ability to detect the specific relationship between scrupulosity and OCD symptoms. Fourth, our sample was heterogenous with regard to symptom presentation, so scrupulosity may have been irrelevant to the symptoms of some participants. Future research should investigate similar questions in a sample of individuals with primary scrupulosity symptoms. Fifth, the small number of patients who identified as Jewish, relative to the number of patients who identified as Catholic, Protestant or as having no religion, may have prevented the relationship between scrupulosity and OCD symptoms in that group from reaching statistical significance. This small subsample may also impact the stability of correlations among Jewish individuals.

Although the current study captured several common religious affiliations, findings do not speak to potential differences in scrupulosity and OCD symptom severity in other common religions, such as Islam. Finally, the present study measured religious identity, but not religiosity – the degree to which one's religious identity is central to their sense of self. Future research should assess strength of religiosity and level of involvement with religious practice to improve the accuracy of findings about religious affiliation and OCD phenomena. Despite these limitations, the current study adds to our understanding of the nature of scrupulosity in OCD and may facilitate the identification of more precise targets for intervention.

Conflicts of interest: Jennifer L. Buchholz, Jonathan S. Abramowitz, Bradley C. Riemann, Lillian Reuman, Shannon M. Blakey, Rachel C. Leonard and Katherine A. Thompson have no conflicts of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statement: All authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the APA. The consent procedures and study measures were approved by both the Human Subjects Committee and the Rogers Center for Research and Training.

Financial support: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for profit sectors.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.