Introduction

Questions can too often be seen simply as a means of eliciting information. The appreciation of the power of questions and the use of questions with specific therapeutic purposes only began during the 1970s as an aspect of a group of therapies, including Brief Therapy and Problem-Solving Therapy (McGee, Del Vento and Bavelas, Reference McGee, Del Vento and Bavelas2005). Within cognitive therapy (CT), questions are used to explore issues from different angles, create dissonance, and facilitate re-evaluation of beliefs, whilst at the same time building more adaptive thinking styles. Skilfully phrased questions can help to highlight either links or discrepancies in the client's thinking (Overholser, Reference Overholser1993) and lead to new discoveries. Questioning techniques can also assist clients to gain greater clarity and understanding of their thinking processes.

To date, the majority of the literature examining the use of questions within therapy has focused on Socratic questioning (Carey and Mullan, Reference Carey and Mullan2004; Overholser, Reference Overholser1993). There is less research examining the more general use of questions in therapy. The questioning process is a dynamic one, requiring different types and sequences of questions at various stages of therapy. We suggest that therapists, particularly those in training, are not always aware of the quality and power of some of the questions they ask (James and Morse, Reference James and Morse2007). As part of developing competence in our questioning abilities, Overholser (Reference Overholser1993) argues that an understanding of question formats is essential. This paper attempts to examine some of the formats and features associated with “questioning”.

Question function and form

Questions serve a range of functions, from gathering information to invoking interest or encouraging critical thought and evaluation, to name but a few. Regardless of their function, a question constrains the recipient to answer within a framework of assumptions set by the question. Whether the function of the question is met depends on the “correct” type of question being asked. As a result, it is important for therapists to have a good understanding of the differing functions of questions.

McGee (Reference McGee1999) proposes a model detailing how questions work in psychotherapy that is based on the microanalysis of the communication between therapist and client. The model uses several principles from research on language and communication. According to the model, there are 10 functions of questioning that relate to each and every question asked in psychotherapy, regardless of the type of question (McGee et al., Reference McGee, Del Vento and Bavelas2005).

First, the model acknowledges that questions require answers and that, in order to answer a question, the client must make sense of the question. This requires the client to take the perspective of the therapist. The model also states that questions constrain and orient the client to a particular aspect of her experience, meaning that the topic of the answer is fixed by the question. Additionally, in order to answer the question, clients must review their personal experiences and knowledge and may be required to formulate opinions in a relatively short space of time. This can be demanding of attention and concentration. A further point made by the model is that questions generally assume a certain amount of information and clients tend to accept these assumptions when answering questions. These assumptions can be changed but, once the client has answered, they tend to be accepted. The model also suggests that the answer is owned by the client as opposed to the therapist. Finally, the model states that, having answered the question, the initiative returns to the therapist and that, as conversation continues, it becomes increasingly difficult to address assumptions agreed upon earlier in the conversation.

This model highlights the complexity of asking questions in psychotherapy as it indicates the power imbalance between therapist and client, the power of questions to dictate what is accepted and spoken about, and the amount of work required by the client to answer the question. This suggests that therapists need to think very carefully about the particular types of questions asked.

Hargie and Dickson (Reference Hargie and Dickson2004) distinguished between several types of questions. At one of the most basic levels, there are open or closed questions. Open questions are broader in nature and can be answered in a number of ways, while closed questions usually elicit a shorter response, selected from a limited number of options. At the cognitive level, Hargie and Dickson distinguished between recall and process questions. They argued that the recall of information requires a lower level of cognitive demand, while process questions go beyond remembering and requires the person to do something with the information, such as comparing, reflecting, or evaluating. Hargie and Dickson further highlighted affective questions, which relate specifically to emotions, attitudes, feelings or preferences of the respondent. Clearly, an affective question can be either recall, process, open or closed.

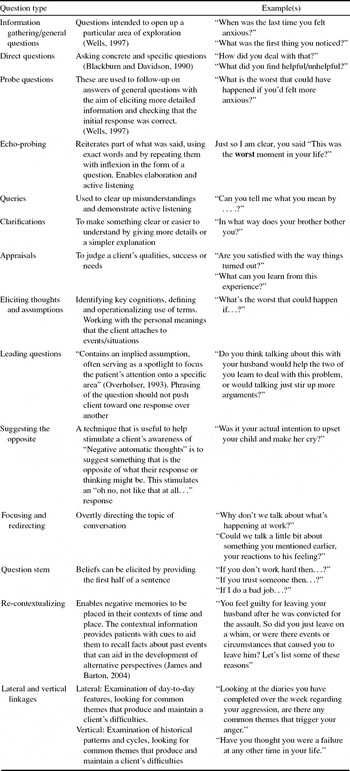

Table 1 summarizes some of the forms of questions that have been highlighted in the CT literature. These follow a logical route from gathering information and clarifying to reaching thought/assumption level, moving on to creating dissonance, shifting the person's thinking and generalizing from this.

Table 1. Examples of types of questions used in CT

While we feel it is helpful to examine question types, it is relevant to note that examining single questions in isolation is overly simplistic due to their impact being a feature of how they are combined and sequenced (McGee, Reference McGee1999).

Questioning techniques

Two common questioning techniques utilized within CT are Socratic questioning and vertical arrow restructuring. Socratic questions may be seen as an umbrella term for a method in which questions are used to clarify meaning, elicit emotion and consequences, as well as to gradually create insight or explore alternative actions (Padesky, Reference Padesky1993; Carey and Mullan, Reference Carey and Mullan2004). Padesky (Reference Padesky1993) outlines four steps in the process, which includes asking informational questions; listening; summarizing; and using synthesizing or analytical questions. She emphasizes that the final step is often neglected by inexperienced therapists; although it plays a vital role in helping the client to re-evaluate his/her original concern or belief.

Vertical arrow restructuring (or “downward arrowing”) (Burns, Reference Burns1980; Wells, Reference Wells1997) is a questioning technique used in the exploration of underlying beliefs and meanings. Here the meaning of an automatic thought is repeatedly questioned in order to determine the “bottom line”. Characteristic questions of this process include: “If that were to happen, what would it mean to you?” or “If that were true, what would be so bad about that?” Thus, this approach questions the meaning of the catastrophe inherent in the client's negative automatic thought. In contrast, Wells (Reference Wells1995, Reference Wells1997), taking a meta-cognitive perspective, suggests that the vertical arrow should be focused on the implications of having particular types of thoughts (e.g. “What's so bad about thinking that?”).

The impact of client characteristics on questions

Prior to examining questions and questioning style in detail, let us reflect on the parameters they are operating within when being used in the field of mental health. All forms of communication should be adapted to meet clients’ needs, taking into account the characteristics and possible processing deficits inherent in the clients’ disorders. The importance of this will be illustrated by taking depression as an example.

Brain scanning evidence has revealed marked changes with respect to brain functioning in depressed people (Drevets and Raichle, Reference Drevets and Raichle1995). Of particular interest to therapists (James, Reichelt, Carlsson and McAnaney, Reference James, Reichelt, Carlsson and McAnaney2008) are changes occurring in the frontal lobes, which are situated in the anterior of the brain, and govern many high level intellectual processes including problem solving skills, conscious processing, and abilities to sustain and shift attention. Disruption to this area due to low affect may lead to a deterioration of these processes (dys-executive syndrome), changes in personality (disinhibition, irritability, egocentricity, loss of insight), behaviour (loss of initiative) and emotions (lability, anxiety, frustration, anger) (Gazzaniga, Ivry and Mangun, Reference Gazzaniga, Ivry and Mangun2002, p. 499).

Psychometric studies of people experiencing depression also reveal marked information processing deficits. While some of these can be related directly to frontal lobe dysfunction, others, such as memory problems, demonstrate the more diffuse impact of depression (Cassens, Wolfe and Zola, Reference Cassens, Wolfe and Zola1990).

In addition to executive and memory problems, depression often leads to changes in people's view of the world, future and themselves. These intrapsychic changes tend to be negatively biased, and the emerging perceptions are often not open to rational re-evaluation. Furthermore, depression typically interferes with someone's ability to maintain interpersonal networks, with the person not enjoying other's company and/or avoiding friends. Conceptualizing depression in terms of these different domains helps one to appreciate the experiences a person with depression may be coping with when he/she comes for treatment.

Thus a therapist treating a depressed client must take account of the executive and memory difficulties, poor motivation, limited attentional capacity, biased thinking and interpersonal difficulties when formulating questions. A competent questioning style would involve short, clear, and concrete questions. While the questions used may have diverse functions, they would need to be well ordered and supportive in nature rather than overly-complex and interrogative (James and Morse, Reference James and Morse2007).

Effective questioning

Overholser (Reference Overholser1993) argues that good questioning often involves using short sequences, alternating between Socratic and non-Socratic dialogue. Others suggest that the therapist's questioning technique should reveal a constant flow of inquiry from concrete and specific to abstract and back again (Blackburn and Davidson, Reference Blackburn and Davidson1990; Padesky, Reference Padesky1993). Further, it is suggested that questions aimed at aiding discovery should ideally be phrased within, or just outside, the client's current understanding in order that she/he can make realistic attempts to answer them (James, Reference James2001). The exact nature of the questions asked will reflect the interaction between the client and therapist, the client's level of understanding, their communication, and suitability for therapy (Safran and Segal, Reference Safran and Segal1990).

The form of the questions will also be consistent with the principles outlined in cognitive therapy competence scales (e.g. Manual to Cognitive Therapy Scale – Revised, James, Blackburn and Reichelt, Reference James, Blackburn and Reichelt2001; Blackburn et al., Reference Blackburn, James, Milne, Baker, Standart, Garland and Reichelt2001) with respect to competent therapy. That is, the questions will be clear, appropriately paced, well-structured and delivered in an interpersonally effective manner.

There is some debate concerning whether therapists should already know the answer to the questions that they are asking (c.f. Wells, Reference Wells1997). It has been suggested that good questions are those asked in the spirit of inquiry, while bad ones are those that lead the client to a pre-determined conclusion (James et al., Reference James, Blackburn and Reichelt2001). As Padesky (Reference Padesky1993) puts it, “sometimes if you are too confident of where you are going, you only look ahead and miss detours that could lead you to a better place”.

Padesky (Reference Padesky1993) argues that “listening is the second half of questioning”. She suggests that therapists should listen for idiosyncratic words and emotional reactions, and also listen to any metaphors and mental images that clients describe. It has been argued that listening for these unexpected pieces of a client's story, and reflecting them back, will often intensify a client's affect and create new and faster in-roads (Padesky, Reference Padesky1993).

Skilful questioning places great demand on the therapist, who needs to recall information from previous sessions, attend to information provided within the current session, whilst planning how and where to take this information with further questions. Despite the complexity of dealing with all of these features, many skilled therapists are able to recall, integrate, plan and ask appropriate questions. We believe, however, that reflecting on this aspect of therapy, and potentially increasing self-awareness, would improve clinicians’ questioning skills still further (Bennett-Levy, Reference Bennett-Levy2006).

Poor questioning

Therapists need to be aware of the impact of poor questioning, so they do not misattribute poor clinical outcomes to client resistance or avoidance, rather than their own ineffective questioning. A previous section examined features of depression and highlighted how questions needed to be adapted to the need of the client. In this context, over-complex, multi-layered, and/or poorly sequenced questions will place too great demands on the clients’ (and therapists’) information processing and can thus be unhelpful. There are a number of challenges in maintaining a clear sequence of questions, for example, staying with ‘hot cognitions’ and not being led away by tangential negative automatic thoughts. Padesky (Reference Padesky1993) also cautions about asking a series of unrelated questions that have doubtful relevance to the client's concerns.

James and Barton (Reference James and Barton2004, p. 436) highlight that trainee therapists may ask too many questions at the “theory building” levels, and get “stuck in an assessment and re-conceptualization loop”. Such a loop often means there is no product from the process, and thus one may end up generating more and more examples of negative thoughts and beliefs, without ever making an intervention. This may make the person more depressed.

In addition, if delivered in a mechanical and “unfeeling” manner, questions can have adverse effects (Hargie and Dickson, Reference Hargie and Dickson2004), making the client more confused, and perhaps undermine self-esteem (“I must be stupid, I can't even answer my therapist's questions”). Poor questions can also make the client feel interrogated or misunderstood, thus impacting on subsequent attendance.

Frameworks for asking questions

A key issue concerns how to maximize the effectiveness of our questions. We believe that the real skill of asking questions lies in being clear about their functions, and therefore questioning styles will vary according to what one wants to achieve. Having a framework for particular questioning sequences may facilitate the use of more effective questions. A suitable framework may provide a series of clear sub-goals, allowing questions to be asked in a more focused way. There are a few frameworks available in the literature.

Within the educational literature, Bloom (Reference Bloom1956) identified six categories for classifying different levels of questions: eliciting knowledge, eliciting comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, evaluation. These aspects appear relevant to therapy. For example, eliciting knowledge and comprehension are essential and common aspects of all stages of the therapeutic process. The application of new therapeutic insights to real life situations is frequently observed in homework assignments. The analysis of information is used in many areas, but is crucial when helping clients to re-evaluate thoughts. Synthesis is apparent in conceptualization and feedback phases, whereby questions determine whether the client has understood key concepts. Evaluation involves asking clients to reflect on the value of the formulation or specific techniques being used.

Overholser (Reference Overholser1993) examined the application of Bloom's classification to the Socratic method. He argues that Socratic questions are more likely to encourage the analysis, synthesis, and evaluation of different sources of information. This suggests that Socratic questioning utilizes “higher” thought processes and may ultimately have greater impact on change.

Another framework, adapted from the educational literature, is the “scaffolding and platforming” model (James, Milne and Morse, Reference James, Milne and Morse2008). Scaffolding strategies take the form of verbal and non-verbal statements (questions, cues, reminders, prompts, contexts) that guide the client's learning and progress (Vygotsky, Reference Vygotsky1978; Wood, Bruner and Ross, Reference Wood, Bruner and Ross1976). In a recent project examining micro-skills involved in the supervision of a neuropsychology case (James, Allen and Collerton, Reference James, Allen and Collerton2004), it was suggested that the notion of scaffolding (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Bruner and Ross1976) was a helpful way to understand how an instructor guided a learner within a learning situation. Scaffolding is defined as the process by which an instructor (i.e. therapist or supervisor) provides temporary support to a learner (i.e. client or supervisee) in order to help her learn something using her existing knowledge. For example, before asking a client to demonstrate how to complete a “thought diary”, some scaffolding might be required, particularly if one is aware that the client cannot remember how to perform the task. So, in order not to embarrass the client and thereby reduce self-esteem further, one might provide some contextual cues in the form of statements, reminders and questions (i.e. scaffolds). One may remind the person of the basics of the CT rationale; asking her to recall the last time she completed the diary, including problems she may have experienced; one could also ask the client how the diaries might be useful in the treatment of her depression. If we explore these various aspects of diary keeping, we can give the client enough cues to show her how to complete the diary better.

The following section provides a further example, and includes dialogue by way of illustration. The goal in this scenario was to get a client to increase the flexibility of her beliefs concerning the degree to which she could control aspects of her depression. At the outset, she viewed depression as genetic in origin, and that she had neither control over it nor its consequences. This view had left her in a helpless and hopeless position. The questions outlined below aimed at helping her bring the relevant information, including the inconsistencies, into the arena.

Therapist (Th) 1: Everyone's depression is different, so what's your understanding of the reasons for you feeling so low?

Client (Ct): It's in my genes – it's that simple. I have no control over this.

Th 2: OK, so it sounds like you think you've a vulnerability within your make-up. Is that right?

Ct: Like the rest of my family. . .. . . like my dad and uncle, I've just got to bear it.

Th 3: Thanks for being so honest. Let me ask a little about your experience of being depressed. We all experience low mood differently. I even bet those in your family have slightly different experiences of their depression. So it's important to check-out how it is affecting you. Now, do you recall which areas of your life I asked you about in the “depression scale” I used earlier?

Ct: Yeah, you asked about difficulties with my sleep, sex life and whether I felt hopeless!

Th 4: Sure, well remembered. I also asked whether you've stopped doing things you used to enjoy, whether you were feeling anxious. . . what times were the worst. I'd also be interested in you telling me more about how you're getting on with others – you mentioned something about your brother. Would you tell me something about these areas?

Ct: I feel crap all the time, with least energy in the morning. My brothers complain I don't go out, but when I go out they say I complain all the time. Also, as well as feeling sh*t, I look sh*t. So what's the point of doing anything?

Th 5: Gosh, I can see why that seems so bad for you. . . Right, so let me recap to make sure I've fully understood. . . so you think you have a genetic tendency to get depressed, which you may or may not have any control over. Your depression also causes you to struggle in the mornings, makes you feel sh*t and has caused you to take less care of your appearance. It is also causing some difficulties with your relationship with your family, particularly your brothers. So is it correct to say that the depression has affected your ability to do things as well as your motivation to do them?

Ct: That sums it up. You know, people used to ask me where I got my hair cut, ..or bought my clothes. Well, I haven't washed my hair for days, and now I spend most of the day in old T-shirts and shorts.

Th 6: Of all these things you've just mentioned: “wearing the old clothes”, “complaining to brothers”, “problems in the morning”, “not washing hair”, “not going out”, which of these are completely out of your control and under the influence of your genes?

In this scenario, the client is asked to reflect in more detail about her depression. The therapist is aware that the client is the expert with respect to her own depression, and so gets her to generate features associated with her depression. He knows, from CT theory, her view that all aspects of her depression are outside of her control is likely to reflect a depressiogenic bias. This inconsistency in her reasoning produces the therapeutic space to generate cognitive dissonance, which may be exploited by the therapist to create change. The scaffolding in this example involves cueing the client to build-up a richer description and understanding of her depression. The various conceptual “jigsaw pieces” representing her experience of depression are generated chiefly by the client and are now on view, permitting inspection and reconstruction into a more consistent and balanced interpretation.

The actual scaffolding procedure takes the form of directions (gestures, questions, instructions, cues and prompts) from the therapist. They depend on the observed responses of the client with the material under discussion. So, if the client starts to look confused or anxious, this cues the therapist to use simpler language, repeat key issues, or tackle the situation from a new perspective. Such adaptiveness is similar to the notion of “responsivity” from the psychotherapy literature (Stiles and Shapiro, Reference Stiles and Shapiro1994).

Another important aspect to the scaffolding process is the “platform”, which is defined as the supportive information (summaries, reminders, or statements) used to set-up a question or to give it an appropriate context. Thus platforms serve to guide and direct the clients’ responses. In the above example, the “Th 5” sequence is a platform. It is a type of summary, but fashioned as a spring board to direct further therapeutic work. So, in addition to summarizing, it usually highlights a concept that becomes the focus of the next bit of dialogue. In the above case, the platform emphasizes the fact that some features of the client's depression are influenced by motivation rather than her genes (i.e. statement “Th 5” sets-up “Th-6”).

Implications for training

Asking questions in therapy is a complex skill. A better understanding of questioning techniques and their use in the therapeutic process has the potential to benefit the training of therapists and treatment outcomes.

Therapists’ skills may be improved by getting them to increase their self-awareness of the types of questions they use and the way in which they use them. Such self-reflection could be achieved through discourse analysis of video-recordings of their therapy sessions. Abilities may be further enhanced through the use of structured role-play sessions, with feedback received from peers and supervisors. Evidently, these sessions could also be taped to facilitate more reflection and critical analysis.

In addition, there is a need to examine the questioning abilities of skilled therapists. These skilled clinicians could be asked to go through tape-recordings of their sessions, providing rationales for the various questioning techniques used and giving reasons for changes in strategy and focus.

It is worth noting that the development of “competent questioners” is also relevant to other professions: for example, teachers, barristers, police negotiators. Hence, a more general review of the area would prove a useful exercise.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.