Introduction

Intolerance of uncertainty referred to the “predisposition to react negatively to an uncertain event or situation, independent of its probability of occurrence and of its associated consequences” (Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur, Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994). A person characterized by a high level of intolerance of uncertainty may find many aspects of life intolerable, given that life is filled with uncertainty and ambiguity. Freeston et al. (Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994) demonstrated that there was a unique link between IU and worry, which was independent of levels of anxiety and depression.

Most researchers used the Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS; Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994) to measure IU. There were several language versions of the IUS, including a French and an English version. The French version was developed to assess emotional, cognitive, and behavioural reactions to ambiguous situations, implications of being uncertain, and attempts to control the future. Factor analysis identified a five-factor structure that included: (1) beliefs that uncertainty was unacceptable and should be avoided; (2) being uncertain reflected badly on a person; (3) uncertainty resulted in stress; (4) frustration related to uncertainty; and (5) uncertainty prevented action (Dugas, Freeston and Ladouceur, Reference Dugas, Freeston and Ladouceur1997; Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994). The psychometric properties of the English version of the IUS were examined by Buhr and Dugas (Reference Buhr and Dugas2002) and the factor analysis identified a different four-factor structure that included: (1) uncertainty was stressful and upsetting; (2) uncertainty led to the inability to act; (3) uncertain events were negative and should be avoided; and (4) being uncertain was unfair.

The IUS was first translated from English to Chinese by two independent translators. Another translator then translated it back into English and problem items were identified and modified. Finally, a pilot version was administered to a small group of participants. This study offered information concerning the internal consistency, test-retest reliability, factor structure, and convergent and divergent validity using symptom measures of worry, depression, and anxiety in a non-clinical sample and provided evidence that the Chinese version of the instrument was acceptable.

Method

Participants

Participants in this study were students of Weifang Medical College, China (N = 973). Students participated voluntarily and they could receive course credits for participation. The participants all gave informed consent. Of the 973 students, 940 completed the questionnaires (473 men and 467 women; mean age = 20.79 years, SD = 2.06, range = 18–25).

Measures

The Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale (IUS; Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994) consists of 27 items on a 5-point scale. The French and English versions of the measure had excellent internal consistency, good test-retest reliability and demonstrated convergent and discriminant validity (Dugas et al., Reference Dugas, Freeston and Ladouceur1997; Buhr and Dugas, Reference Buhr and Dugas2002).

The Penn State Worry Questionnaire (PSWQ; Meyer, Miller, Metzger and Borkovec, Reference Meyer, Miller, Metzger and Borkovec1990) is used to measure trait-like worry. PSWQ consists of 16 items for measuring the frequency and intensity of worrying.

Self-rating Depression Scale (SDS) is a 20-item self-report measure of the symptoms of depression. Subjects rate each item according to how they felt during the preceding 7 days (Zung, Reference Zung and Guy1976).

Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) measures affective and somatic symptoms of an anxiety disorder. The structure of the SAS is like that of the SDS. It also consists of 20 questions that refer to the past 7 days (Zung, Reference Zung1971). The SDS and SAS have been widely used in China and have been proved by many researchers to have very good reliability and validity (Wang, Wang and Ma, Reference Wang, Wang and Ma1999).

All instruments were administered in Chinese. If available, official, copyrighted translations were used with permission. For the other non-Chinese scales, the English-version instruments as fully described in the original articles were translated following a back-translation approach. It is important to note that the Chinese versions of the PSWQ (Sha, Wang, Liu and Zhong, Reference Sha, Wang, Liu and Zhong2006), SAS and SDS (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Wang and Ma1999) had satisfactory psychometric properties. In addition, a group of 80 participants previously tested were asked to complete the IUS for a 5-week retest of the measure.

Results

The means of the IUS of the Chinese undergraduates was 71.78 ± 15.13 and significantly higher (t = 15.83, p < .001) than that of the French-speaking Canadians (54.78 ± 17.44) (Buhr and Dugas, Reference Buhr and Dugas2002). This suggested that, compared with French-speaking Canadian undergraduates, Chinese undergraduates were more likely to avoid risks and had lower tolerance of vague, disorderly and uncertain situations; this may be related to the different cultural influences and socioeconomic levels in the two countries.

The internal consistency of the IUS was excellent (α = 0.90) and item-total correlations ranged from 0.32 to 0.61. A group of 80 participants were re-tested on the IUS after 5 weeks, and the reliability coefficient was r = 0.75.

An exploratory principal components factor analysis with Oblimin rotation was performed on the 27 items of the IUS. Kaiser's measure of sampling adequacy for the intercorrelation matrix was 0.91. Seven factors were found with an eigenvalue >1 (i.e. 6.62, 1.75, 1.37, 1.18, 1.09, 1.06, and 1.01), and on the basis of the scree-plot, a more appropriate factor solution with less than five factors may be included.

Furthermore, a Promax (oblique) rotation was employed to identify the underlying factor structure. The scree test and item loadings were used to identify a four-factor solution as the best representation of the results. Four eigenvalues were identified for this solution which were 7.52, 7.12, 6.31 and 5.53 and the solution accounted for 52.1% of the variance.

In keeping with the factor analysis of the French version and the English version, loadings of 0.30 or greater were considered for inclusion of items on factors. Factor one consisted of 10 items and represented the idea that uncertainty led to the inability to act. Factor two consisted of 11 items indicating that uncertainty was stressful and upsetting. Factor three consisted of nine items, referring to the idea that unexpected events were negative, and should be avoided. Factor four consisted of six items that suggested that being uncertain was unfair. This result was similar to that of the English version of the IUS (Buhr and Dugas, Reference Buhr and Dugas2002).

The correlations between the factors ranged from 0.42 to 0.66 (p < .001). All four factors were highly correlated with the overall IUS score and the correlations ranged from 0.65 to 0.89, p < .001.

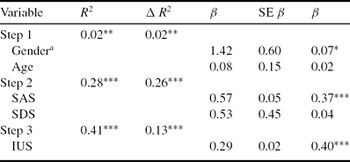

All questionnaires (i.e. PSWQ, SAS and SDS) correlated significantly with the IUS (range from 0.41 to 0.56). When controlling for the SAS, SDS, and both SAS and SDS respectively, the partial correlations between the IUS and PSWQ were all significant (r = 0.44, 0.43, 0.41; p < .001, N = 940). These results showed that the significant correlation between the intolerance of uncertainty and worry still remained after partialling out anxiety and depression. A hierarchical regression analysis was performed to determine which variables contributed to the prediction of worry. Gender and age were entered at the first step, SAS and SDS at the second step, whereas the IUS was entered at the third and last step. The results showed that after controlling for demographic variables, depression and anxiety, the IUS still accounted for a significant additional 13% of variance in PSWQ scores (see Table 1).

Table 1. Summary of hierarchical multiple regression analyses for variables predicting scores on the PSWQ (N = 940)

Notes: PSWQ = Penn State Worry Questionnaire; SAS = Self-rating Anxiety Scale; SDS = Self-rating Depression Scale; IUS = Intolerance of Uncertainty Scale.

a Gender coding: 1 = Male; 0 = Female.

*p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Discussion

Overall, this study demonstrated that the Chinese version of the IUS had satisfactory psychometric properties for research use. It had excellent internal consistency and good test-retest reliability. The results indicated that the Chinese version of the IUS was as effective as the French version (Freeston et al., Reference Freeston, Rhéaume, Letarte, Dugas and Ladouceur1994) and the English version (Buhr and Dugas, Reference Buhr and Dugas2002).

Factor analysis of the IUS indicated that a four-factor structure was verified. This was similar to the English version but different from the French version, which had five factors. The French version of the IUS had a factor named “being uncertain reflected badly on a person”, which did not exist in the English and Chinese versions. The English version and the Chinese version both had a factor named “being uncertain was unfair”, which did not exist in the French version. The difference between the Chinese and English versions was in the number of items in each factor; in the Chinese version they were 10, 11, 9, 6 respectively, whereas in the English version they were 10, 12, 7, and 5.

The correlation analysis indicated that the four factors were all significantly related to the overall scores of the IUS and there was not much difference between those correlation coefficients. We therefore followed the recommendation of the English version (Buhr and Dugas, Reference Buhr and Dugas2002) to use the total scores of the IUS in future research. The results of the correlation matrix and the regression analysis demonstrated that the concept of intolerance of uncertainty was a very relevant factor for the study of worry.

Generally, the Chinese version of the IUS was a reliable and valid scale for assessing the intolerance of uncertainty. However, two limitations of the present study should be mentioned. The first limitation was that the participants in the study were from a non-clinical sample. The second limitation was that our non-clinical sample consisted only of undergraduate students and therefore the results could not be generalized to other types of community samples.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the Humanities and Social Science Fund, Youth Project, Chinese Ministry of Education (10YJCXLX050) and the Science and Technology Fund, Youth Project, Beijing Forestry University (2010BLX19).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.