Introduction

Several studies have shown the effectiveness of schema therapy, mainly for adult patients with borderline personality disorder (Dickhaut and Arntz, Reference Dickhaut and Arntz2014; Giesen-Bloo et al., Reference Giesen-Bloo, Van Dyck, Spinhoven, Van Tilburg, Dirksen, Van Asselt and Arntz2006; Farrell et al., Reference Farrell, Shaw and Webber2009; Nadort et al., Reference Nadort, Arntz, Smit, Giesen-Bloo, Eikelenboom, Spinhoven and van Dyck2009), but also as a treatment of other personality disorders (Bamelis et al., Reference Bamelis, Evers, Spinhoven and Arntz2014). Promising results have further been found for other complex disorders, such as recurrent depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, eating disorders, and obsessive-compulsive disorders (Cockram et al., Reference Cockram, Drummond and Lee2010; Malogiannis et al., Reference Malogiannis, Arntz, Spyropoulou, Tsartsara, Aggeli, Karveli and Zervas2014; Simpson et al., Reference Simpson, Morrow and Reid2010; Renner et al., Reference Renner, Arntz, Peeters, Lobbestael and Huibers2016; Thiel et al., Reference Thiel, Jacob, Tuschen-Caffier, Herbst, Külz, Hertenstein and Voderholzer2016).

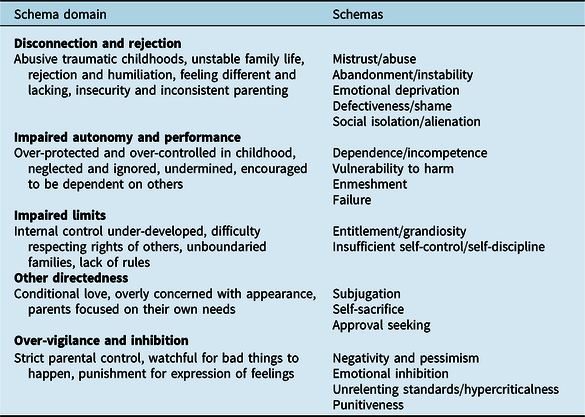

The central concept of the schema therapy model is the early maladaptive schema (EMS). EMS is defined as a persistent and pervasive pattern of information processing, thoughts, emotions, memories, and attention preferences (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003). EMS develop in childhood and adolescence through the interaction of aversive childhood experiences with biological and temperamental factors. Every child has basic needs for safety, love, attention, acceptance, autonomy and adequate limit setting for a healthy personality development to occur. When these basic needs are not fulfilled, EMS develop. Young and colleagues (Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003) identified 18 EMS, organized into five schema domains (see Table 1). For example, when the core emotional need for safety is not met because of a violent parent, this may give rise to the mistrust/abuse schema. Secondary factors that also contribute to the development of EMS are culture, birth order, the quality of the parent’s marriage, and the child’s temperament (Louis and Louis, Reference Louis and Louis2015). Maladaptive schemas may also develop in adult life following deeply traumatizing experiences, although this is considered to occur rarely (Louis et al., Reference Louis, Wood, Lockwood, Ho and Ferguson2018). A recent study identified a four-schema domain solution as more appropriate in terms of interpretability and empirical indices instead of the original five-schema domains (Bach et al., Reference Bach, Lockwood and Young2018). Interestingly, all four schema domains meaningfully accounted for the association between need-thwarting parental experiences in childhood and current negative emotional states (‘vulnerable child mode’) in adulthood.

Table 1. Early maladaptive schemas (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003)

The concept of EMS is closely related to the schema construct in cognitive psychology. Schemas are defined as superordinate knowledge structures, which reflect commonalities across multiple experiences, and influence how events are perceived, interpreted and remembered. Recent studies demonstrate distinctive neurobiological processes underlying schema-related learning (Gilboa and Marlatte, Reference Gilboa and Marlatte2017).

EMS are likely to be even more rigid and impervious to disconfirming information than schemas in general, because they are presumed to be made up of more tightly interconnected knowledge structures (Louis et al., Reference Louis, Wood, Lockwood, Ho and Ferguson2018). Activated EMS strongly influence how people perceive themselves and others through mechanisms of selective attention, encoding of stimuli and selective retrieval of schema-associated information (Arntz and Lobbestael, Reference Arntz, Lobbestael, Livesley and Larstone2018). Schema therapy has been found to reduce EMS while also improving symptoms for personality disorders (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bee and Haddock2017), and in chronic depression (Renner et al., Reference Renner, DeRubeis, Arntz, Peeters, Lobbestael and Huibers2018). However, sound mediation-analytical studies have not been conducted yet, and evidence for other mental health disorders than personality disorders and depression is sparse (Taylor et al., Reference Taylor, Bee and Haddock2017).

Until recently, schema therapy in older adults was neglected (Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van Royen and Van Alphen2012). Possibly, this is due to the therapeutic nihilism that still prevails concerning the feasibility and effectiveness of psychotherapy for personality disorders in later life. Many believe that the aim of changing pathological aspects of personality is not possible in older adults, because of the rigidity of lifelong dysfunctional patterns or the consequences of cognitive and physical decline (Van Alphen et al., Reference Van Alphen, Derksen, Sadavoy and Rosowsky2012b). Nowadays, clinical attention is growing for schema therapy as a promising treatment approach in later life, as it connects to the psychotherapy expectations of older adults (Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Rossi, Van Royen, Rosowsky and Van Alphen2015). In later life, many older people with personality pathology seek help because they fail to cope with life events that disrupt their psychological homeostasis, like chronic illness, disability, and the loss of loved ones. Sometimes, as people age, they are motivated for psychotherapy by their shrinking life horizon, with a perceived finite boundary on their time to invest in meaningful goals (Laidlaw and McAlpine, Reference Laidlaw and McAlpine2008; Plotkin, Reference Plotkin2014). Moreover, many older patients have never received (adequate) psychotherapeutic treatment earlier in their lives. Older people with personality disorders have been severely undertreated, as evidence-based treatments for personality disorders were not developed until the end of the last century.

Case studies have already indicated that individual schema therapy was feasible for personality disorders in older adults (Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Rossi, Van Royen, Rosowsky and Van Alphen2015; Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van Royen, Van Alphen, Rossi and Van der Feltz-Cornelis2017). So far, two empirical studies have been conducted into schema therapy with older people. The first study was designed as a proof of concept study, in which the feasibility of short-term group schema cognitive behaviour therapy (Broersen and Van Vreeswijk, Reference Broersen, Van Vreeswijk, Vreeswijk, Broersen and Nadort2012) was investigated in older people with a mean age of 67 years, with personality disorder features and longstanding mood disorders (Videler et al., Reference Videler, Rossi, Schoevaars, Van der Feltz-Cornelis and Van Alphen2014). As proof of concept intermediate analysis, it was investigated whether the intervention induced changes in EMS, and whether this mediated changes in symptoms. Results showed that group schema therapy led to significant improvement in symptomatic distress from pre-treatment to post-treatment. Further analysis showed that changes in EMS mediated changes in symptomatic distress. This finding was regarded a proof of concept that short-term group schema therapy decreases EMS and thus lessens symptomatic distress in older adults. The second study provided the first empirical support for the effectiveness of individual schema therapy in later life using a case series multiple-baseline design with older patients with a cluster C personality disorder (Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van Alphen, Rossi, Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Van Royen and Arntz2018). Currently, a similar multiple baseline study is being conducted into schema therapy for borderline personality disorder in older adults (Khasho et al., Reference Khasho, van Alphen, Heijnen-Kohl, Ouwens, Arntz and Videler2019). Although these studies among older people are promising, no randomized controlled trials (RCT) have evaluated schema therapy in later life yet. One RCT has begun in the Netherlands and studies the (cost-) effectiveness of group schema therapy, enriched with psychomotor therapy, which is adapted to the needs of older adults with cluster B and/or C personality disorders (Van Dijk et al., Reference van Dijk, Veenstra, Bouman, Peekel, Veenstra, van Dalen and Voshaar2019).

Positive schemas

Lockwood and Perris (Reference Lockwood, Perris, van Vreeswijk, Broersen and Nadort2012) introduced the concept of early adaptive schemas (EAS) as the positive counterpart of an EMS. Like EMS, EAS consist of persistent patterns of information processing, thoughts, emotions, memories, and attention preferences. However, these EAS serve positive functions and give rise to adaptive behaviour, and they emerge during childhood, when one’s core emotional needs are adequately met by parents or other primary caregivers. Lockwood and Perris (Reference Lockwood, Perris, van Vreeswijk, Broersen and Nadort2012) advocate that because schemas are defined by distinct themes, it can be assumed that positive and negative schemas are separate constructs that get activated by different types of experiences. People experience both EAS and EMS simultaneously. Although the presence and strength of an EMS may negatively predict the strength of the corresponding EAS, a decrease of intensity of an EMS will not always cause a corresponding increase of intensity of an EAS. So, each EAS represents a distinct dimension and is more than the polar opposite of its corresponding EMS.

This conceptualization of EMS and EAS as distinct dimensions was supported by the empirical work of Louis and colleagues (Reference Louis, Wood, Lockwood, Ho and Ferguson2018). They developed the Young Positive Schema Questionnaire (YPSQ) as a complement to the Young Schema Questionnaire-3 Short Form (YSQ-S3; Young, Reference Young2005). As opposed to the original 18 EMS, Louis and colleagues identified a 56-item, 14-factor EAS solution, which was then supported by a multi-group confirmatory factor analysis (see Table 2 for the 14 EAS). The development of the YPSQ allows for a separate measurement of positive and negative schemas. Because the EAS showed incremental validity over and above the EMS, the authors concluded that EAS and EMS are separate constructs, and not just opposite ends of continua (e.g. mistrust versus trust; failure versus success). Another view may be that EMS and EAS can both be conceived of as continua, which start to blend with each other in the middle. This view coincides with our clinical impressions that a diminution in the intensity of a negative schema does not mean there is a corresponding increase in a positive one. People are inclined to hold multiple contradictory beliefs about themselves and the world (Wood & Johnson, Reference Wood and Johnson2016). Their behaviour depends on which particular schema is active at some point in time.

Table 2. Early adaptive schemas (Louis et al., Reference Louis, Wood, Lockwood, Ho and Ferguson2018)

Our hypothesis is that positive schemas may be important vehicles of therapeutic change in schema therapy with older adults. In this article we discuss the possible role of positive schemas, or EAS, in working with older adults. We propose suggestions for integrating EAS in schema therapy into later life, illustrate this with a case example, and conclude with implications for further research.

Schemas and ageing

There is little empirical research on the way EMS manifest themselves in later life, and it is unknown how they evolve over the life course (Legra et al., Reference Legra, Verhey and Van Alphen2017). So far, only Antoine et al. (Reference Antoine, Antoine and Nandrino2008) have explored EMS in older people. They constructed and validated a 44-item schema inventory for older adults, with eventually seven age-specific negative schemas in old age: ‘disengagement’, ‘loss of identity’, ‘refusal to help’, ‘abandonment’, ‘dependence’, ‘fear of losing control’ and ‘vulnerability’. As EMS typically originate in childhood, it is unclear when these seven negative schemas are formed and how they relate to the 18 EMS of the original schema therapy model (Young et al., Reference Young, Klosko and Weishaar2003). Possibly, the seven age-specific schemas that Antoine and colleagues found in their study should not be considered EMS, but more as challenges people commonly face as they grow old. Considering the scarcity of literature on schema theory in later life, Legra and colleagues (Reference Legra, Verhey and Van Alphen2017) performed an explorative Delphi study among experts in schema therapy in older adults. Consensus was achieved concerning the assumption that EMS can change during the life course, although they might not all change to the same extent. Changing contextual factors and roles across the lifespan can either mellow or enhance schemas that have been present from childhood. The experts agreed, contrary to the view of Antoine and colleagues (Reference Antoine, Antoine and Nandrino2008), that change does not take place by the appearance or disappearance of EMS, but through mechanisms of schema triggering and schema coping. The chance that an EMS is activated, like for example mistrust/abuse, can be much greater in the context of becoming dependent for care on other people, while this schema was lingering, when a patient was healthy and independent. Also, the way that people cope with their schemas can change. The intelligent and verbally strong, retired lawyer, who had been abused as a child, coped successfully with his EMS of mistrust, by winning every argument, both in court and in his social life, until he was struck with aphasia after suffering a brain haemorrhage. Amongst other factors, this EMS of mistrust contributed to him feeling very unsafe and during a rehabilitation programme, he assaulted a nurse. Due to failing schema coping, a schema can suddenly manifest itself again – or even for the first time – in old age. So, EMS can be more or less active throughout the lifespan, because of strategies that allow schemas to stay hidden. This is in line with the lifespan course of personality disorder symptoms, that tend to wax and wane from adolescence up to old age, and their presentation depends on contextual factors (Hutsebaut et al., Reference Hutsebaut, Videler, Verheul and Van Alphen2019; Videler et al., Reference Videler, Hutsebaut, Schulkens, Sobczak and Van Alphen2019). Two Delphi studies even point to the existence of ‘late-onset’ personality disorders, having their first manifestation late in life due to a combination of pre-existing maladaptive personality features and contextual and developmental changes (Van Alphen et al., Reference Van Alphen, Bolwerk, Videler, Tummers, van Royen, Barendse and Rosowsky2012a; Rosowsky et al., Reference Rosowsky, Young, Malloy, Van Alphen and Ellison2018). The renewed or even first manifestation of personality disorder criteria may be explained by EMS being less active in middle adulthood. Another explanation might be that EAS were more active in early and middle adulthood, and are triggered less in old age; we will come back to this later on.

For assessing EMS in later life, two schema inventories have been examined in older adults, the Young Schema Questionnaire-Long Form (YSQ-L2; Young and Brown, Reference Young, Brown and Young1994), and the Young Schema Questionnaire, Short Form (YSQ-S3; Young, Reference Young2005). The YSQ-L2 appeared to be an age-neutral instrument in young, middle-aged and older adults in a clinical sample of patients with alcohol and substance use disorders in Belgium (Pauwels et al., Reference Pauwels, Claes, Dierckx, Debast, Van Alphen, Rossi and Peuskens2014). Only 3% of the items of the YSQ-L2 showed differential item functioning, which implies that the vast majority of the YSQ-L2 items were similarly endorsed across the three age groups with the same score on the underlying schema scale. The other EMS inventory that has been studied in older adults, the YSQ-S3, is much shorter than the YSQ-L2, whose length can be especially challenging for the oldest-old (Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Van den Broeck, Dierckx, Segal and Van Alphen2014). However, in a preliminary validation study in a small sample of older adults only 13 of the 18 EMS were found to have acceptable internal consistency (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Brockman, Bailey and Kneebone2019). The entitlement/grandiosity schema in particular showed questionable internal consistency, and the enmeshment schema demonstrated relatively low internal reliability. Therefore, awaiting further research into the YSQ-S3 in later life, the YSQ-L2 is preferable for usage in assessing EMS in older adults for the time being. To assess EAS, the recently developed YPSQ (Louis et al., Reference Louis, Wood, Lockwood, Ho and Ferguson2018) has not been studied in older adults yet.

Positive schemas in schema therapy with older adults

In line with the waxing and waning course of personality disorder symptoms, as discussed earlier, the majority of older personality disorder patients have gathered more ‘wisdom of their years’ and have functioned better in middle adulthood (Hutsebaut et al., Reference Hutsebaut, Videler, Verheul and Van Alphen2019; Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Rossi, Van Royen, Rosowsky and Van Alphen2015, Reference Videler, Hutsebaut, Schulkens, Sobczak and Van Alphen2019). This could be explained by two different processes, in which EMS are less active or EAS are more active in middle adulthood. When circumstances change in late life, EMS can become more prominent. This happens partly because these maladaptive schemas are triggered more often because of age-related factors, like retiring, losing a spouse or somatic diseases. When working with older adults in schema therapy, therapists tend to be focused on diminishing EMS for therapeutic change to occur. As argued earlier, this has also been shown possible in later life (Videler et al., Reference Videler, Rossi, Schoevaars, Van der Feltz-Cornelis and Van Alphen2014, Reference Videler, Van Alphen, Rossi, Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Van Royen and Arntz2018). However, addressing positive schemas may very well be an interesting complementary approach, or it may even be an alternative approach in some instances.

Interestingly, in the Delphi study of Legra and colleagues (Reference Legra, Verhey and Van Alphen2017), the experts also consented on the idea that schemas that are associated with successful roles, are often adaptive. Becoming a grandparent gives new chances to deal with old EMS such as failure (‘with my granddaughter I am caring and attentive where I was not with my own daughter’) or social isolation (‘I am part of the group of grandparents’) by strengthening positive schemas. This is congruent with a reconceptualization of the schema model, in which the 18 EMS schemas are complemented by 14 EAS (Louis et al., Reference Louis, Wood, Lockwood, Ho and Ferguson2018).

James et al. (Reference James, Kendell and Reichelt1999) argued that cognitive behavioural therapy models pay too much attention to the negative action of schemata and fail to acknowledge the action of positive or functional beliefs. Therefore, they presented a framework accounting for the development and maintenance of functional rather than dysfunctional self-beliefs. The common goal of all functional self-beliefs is the achievement of a sense of worth that is crucial in maintaining psychological health. They suggested directing attention to strengthening these positive self-beliefs when conducting therapy with older adults, when they proposed the concept of ‘worth enhancing beliefs’ (WEBs). WEBs tend to have been more active in older adults earlier in their lives, when these positive core beliefs were reinforced (‘nourished’) by specific social roles (James, Reference James, Laidlaw and Knight2008). Without continuous reinforcement, a positive belief cannot operate effectively and will not serve to enhance the individual’s sense of worth. As social circumstances change while a person ages and he loses these nourishing roles, positive self-beliefs are triggered less. Consequently, negative core beliefs may become more influential. James advocated to activate these WEBs again, for example by stimulating patients into acquiring new social roles, which again nourish their positive core beliefs.

However, WEBs are not equivalent to positive schemas. WEBs are positive core beliefs, as opposites to the dysfunctional or negative core beliefs in the cognitive therapy model of Beck (Reference Beck and Salkovskis1996). Negative schemas or EMS are broader concepts, as they refer not only to core beliefs, but also to patterns of information processing, emotions, memories, and attention preferences (James, Reference James2003). In other words, WEBs refer only to the ‘positive core belief’ aspect of EAS.

Integrating EAS in schema therapy with older adults might enhance therapy outcome (Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Rossi, Van Royen, Rosowsky and Van Alphen2015). Assessing and activating EAS, which have been active earlier in life, may strengthen the healthy adult mode. This may also allow for the healthy adult mode to be more easily activated when using experiential techniques, such as imagery rescripting or chair work. This is illustrated in the case example of Mrs K. further on.

Another possible advantage of assessing and activating EAS is that it allows challenging a negative life review. Older patients with personality disorders tend to review their life through the filter of their EMS (Videler et al., Reference Videler, Van der Feltz-Cornelis, Rossi, Van Royen, Rosowsky and Van Alphen2015, Reference Videler, Van Royen, Van Alphen, Rossi and Van der Feltz-Cornelis2017). Redirecting attention to EAS might help patients to take a lifespan perspective from their healthy adult mode. In the treatment of depression, life review has been shown to be highly effective in older adults (Bhar, Reference Bhar, Pachana and Laidlaw2014). Older adults are more inclined to take this positive perspective than younger people as this refers to the psychological task of life review in older age (Butler, Reference Butler1974).

Identifying EAS early in the therapy, in the case conceptualization, may contribute to a higher therapy motivation, as it diverts attention away from being solely focused on negative experiences to positive aspects of the patient. Therefore, we advocate to assess both EMS and EAS systematically and add the most dominant EMS and EAS to the case conceptualization.

Case example

Mrs K., a 67-year-old retired nurse, was referred for psychotherapy by her GP with depression and burn-out. The patient met criteria for other specified personality disorder, with three criteria for each: avoidant, dependent, and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, on the Personality Diagnostic Questionnaire 4 (PDQ-4; Hyler, Reference Hyler1994) and the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Personality Disorders (SCID-5-PD; First et al., Reference First, Williams, Benjamin and Spitzer2016). On the Maslach Burnout Inventory (Maslach et al., Reference Maslach, Jackson and Leiter2016), a high degree of exhaustion and a high level of reduced involvement were evident. Mrs K. was referred to a schema therapist (second author).

Mrs K. had been working as a nurse, which she greatly enjoyed. She had always been devoted to her patients, and was extremely hard on herself in thinking that she never did her work ‘good enough’. She often checked with her superior whether he thought she did her work alright. Over the years she started to feel ever more tired, down and exhausted. She gradually worked less, but even after retirement she still felt exhausted and depressed. She was the youngest of five siblings, and grew up with an authoritarian father, who was distant and uncommunicative. She described her mother as ‘an unpredictable ghost’. Throughout her childhood, there was an atmosphere of fear for her mother’s unpredictable mood swings. Mrs K. coped with going unnoticed, trying her best not to do anything wrong, in order to avoid punishment. She was constantly trying to comply to her mother’s wishes. Mother called her older sister, with whom she was very close, the ‘black sheep of the family’. In her adolescence, this sister became more and more suicidal and eventually she was institutionalized at the age of 16.

Case conceptualization

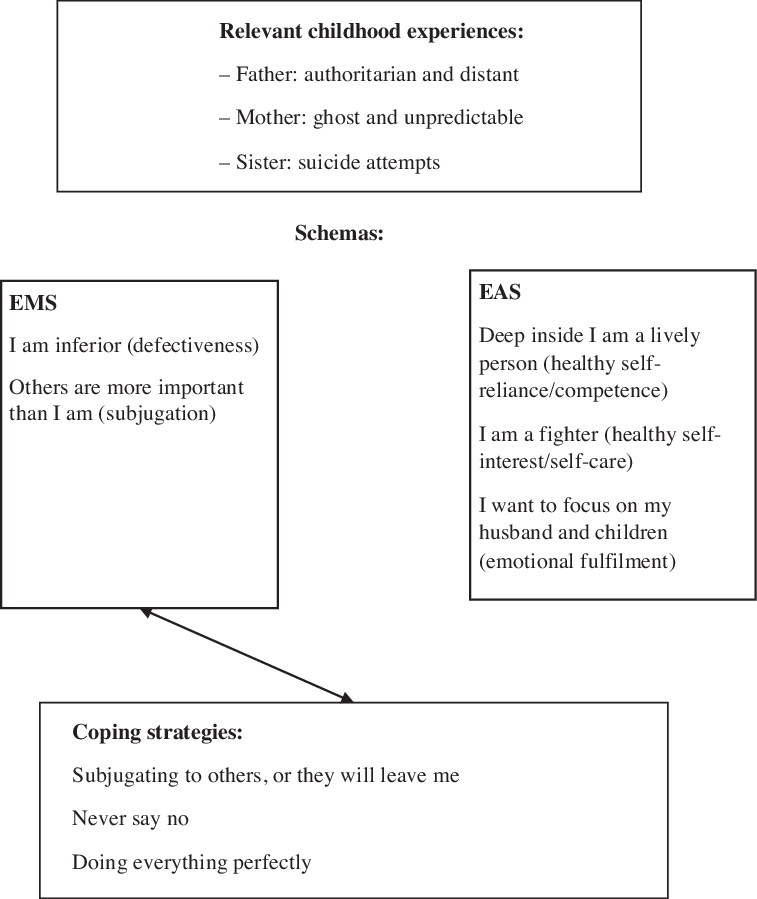

In the assessment and case conceptualization, the therapist and patient collaboratively focused on both her EMS and EAS, rephrasing them into the spontaneous language of Mrs K (see Fig. 1 for the case conceptualization). The YSQ-L2 revealed defectiveness and subjugation as the most dominant EMS. On the YSPQ, highest scores were on healthy self-reliance/competence, healthy self-interest/self-care and emotional fulfilment. For Mrs K., ‘I am inferior’ referred to her EMS of defectiveness, and ‘Others are more important than I am’ to her EMS of subjugation. In exploring the impact of the memories to her sister, Mrs K. concluded that she never wanted a life such as her sister, and finally concluded: ‘I am a fighter’, which referred to her EAS of healthy self-interest/self-care. ‘Deep inside I am a lively person’ referred to the EAS of healthy self-reliance/competence, and ‘I want to focus on my husband and children’ to emotional fulfilment. In exploring both EMS and EAS, Mrs K. realized that these EAS had been lingering there earlier in life, and she regained a more positive view of herself. The hidden aspects of her healthy adult mode became more active, affecting her depressed mood in a positive way. Thereupon, she was motivated to engage further in psychotherapy.

Figure 1. Case conceptualization with positive schemas.

Further therapeutic process

Originally, schema therapy tends to focus on identifying and changing the negative schemas that underlie the long-term problems of patients in order to ultimately build the healthy adult mode. Assessing only EMS with the YSQ may have unintentional side-effects in enhancing the patient’s problematic view of him or herself. Moreover, it omits the resources of the patient. In identifying positive schemas as early as in the case conceptualization, the therapist described Mrs K. as more than her problems. In reawakening the part of the healthy adult by questioning her positive schemas, Mrs K. felt great relief: ‘Deep inside I always vaguely saw myself that way!’. Her EAS of healthy self-reliance/competence, healthy self-interest/self-care and emotional fulfilment had been ‘nourished’ in the past, especially when raising her children, and partially when still working as a nurse. As these EAS were not reinforced sufficiently any more, and also by a diminishing fulfilment in her work and her retirement, her EMS had become more dominant.

As each positive schema is partly a distinct dimension, and not simply the opposite of the corresponding negative schema, for some patients it may not be sufficient to weaken the negative schemas, as a diminution in the intensity of a negative schema will not necessarily induce a corresponding increase in a positive schema (Louis et al., Reference Louis, Wood, Lockwood, Ho and Ferguson2018). It is most likely that enhancing positive schemas might contribute to a better therapy outcome.

To further illustrate the case, we present an outline of the process of a session in which the imagery and rescripting technique was applied to counter Mrs K.’s negative schemas defectiveness and subjugation, and strengthen her EAS. Mrs K. relives the following situation: at the age of 16, she wants to leave home for further education. Her mother disapproves fiercely with her. A few days later, her mother enters her bedroom and says: ‘Tell me, why you want to leave me, do you think I am a bad mother? Say it!’. Mrs K. feels trapped and bows her head to the floor, hoping her mother will leave. She remains silent in fear.

The therapist asks her what she thinks of her mother, now as an adult. Mrs K. says ‘She should not get in the way of my future, my education … a mother cannot do that … she is selfish.’ The therapist prompts the client to try and tell this to her mother. Slowly Mrs K. succeeds in saying: ‘Stop that, go away. I am going to school anyway’. The therapist asks how her mother reacts. Mrs K. says ‘She seems smaller and smaller…’. Then Mrs K. decides to visit her sister who had been admitted to a psychiatric hospital at the time. After this imagery rescripting exercise, Mrs K. realizes that it was the healthy self-interest/self-care schema (the ‘fighter inside her’) who stood up to her mother. Activating this positive schema helped the client to stand up to her mother in the imagery rescripting, and subsequently helped her in standing up for her needs with other people outside the therapy.

Discussion and implications for research

This review discusses the still limited but promising literature on schema therapy and schema theory in older adults, and focuses on the possibly beneficial effects of integrating EAS for enhancing the outcome of schema therapy in later life. As people age, and their EAS are no longer or not sufficiently triggered, EMS may become more prominent. This could partially account for the waxing and waning course of personality disorder symptoms up to old age, whose presentation depends to a large degree on contextual factors (Hutsebaut et al., Reference Hutsebaut, Videler, Verheul and Van Alphen2019; Videler et al., Reference Videler, Hutsebaut, Schulkens, Sobczak and Van Alphen2019). We discussed the possibility that EAS may be potential vehicles of therapeutic change in schema therapy, especially for older adults. Working with positive schemas may be an important avenue for re-awakening positive aspects of older patients, strengthening the therapeutic relationship, and also for facilitating the introduction of experiential schema therapy techniques.

EAS and EMS have been described as separate constructs, although another view may be that EMS and EAS can both be conceived of as continua, which start to blend with each other in the middle. Integrating EAS may also be useful in schema therapy with younger people, but the process in which EAS are less triggered because of the loss of nourishing circumstances for these positive schemas is more typical for ageing people.

Of course, these propositions are hypotheses for further research. First of all, the YPSQ needs to be validated in older adults, preferably in both community-dwelling and clinical samples. Furthermore, we suggest studying whether integrating EAS in schema therapy with older adults indeed has a positive effect on therapy outcome. This could be studied for individual as well as group schema therapy, in older adults with cluster B and C personality disorders.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ian Andrew James for inspiring us.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflict of interest with respect to this publication.

Ethical statement

No ethical approval was needed, as this article has no empirical data.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.