Introduction

While interest in metaphor dates back to Aristotle, modern day metaphor research exploded on the publication of Metaphors We Live By, by linguists Lakoff and Johnson (Reference Lakoff and Johnson1980). Lakoff and Johnson's conceptual metaphor theory suggests that metaphors are more than ornamental figures of speech, instead structuring the way we perceive, how we think and what we do. They argue that metaphors are pervasive in everyday life, with underlying conceptual metaphors, such as ARGUMENT IS WAR Footnote 1 , being shared across speech communities. Cognitive scientists have investigated metaphor experimentally and agree that there are underlying conceptual metaphors in people's production and comprehension of a wide range of figurative language (Gibbs and Nascimento, Reference Gibbs, Nascimento, Kreuz and MacNealy1996; Pfaff, Gibbs and Johnson, Reference Pfaff, Gibbs and Johnson1997). Further, conceptual metaphors are thought to reflect significant patterns of bodily experience. For example LOVE IS A JOURNEY refers to the embodied experience of moving along a path from a starting point to attempt to reach a destination (Gibbs and Franks, Reference Gibbs and Franks2002).

Metaphoric language occurs regularly in psychotherapy, with clients and therapists describing, for instance, the “black cloud” of depression. A metaphor is a figure of speech that implies a comparison between two unlike entities (Stott, Mansell, Salkovskis, Lavender and Cartwright-Hatton, Reference Stott, Mansell, Salkovskis, Lavender and Cartwright-Hatton2010), describing the first subject as “being” or “equal to” a second subject in some way. Metaphors thus act as a bridge between a metaphor vehicleFootnote 2 , which is more concrete or familiar, and a topic that is more abstract or less familiar. Accordingly, the broad definition of metaphor used for this study is “a device for seeing something in terms of something else” (Burke, Reference Burke1945). Interest in the role of metaphor in cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) has increased recently, with enthusiastic practice-based examples of how metaphor, particularly therapist-initiated metaphors, can be used in psychotherapy (Blenkiron, Reference Blenkiron2010; Stott et al., Reference Stott, Mansell, Salkovskis, Lavender and Cartwright-Hatton2010). It has been proposed that client metaphors may: provide therapists with important information about clients’ views of reality (Ronen, Reference Ronen2011); have personal meaning and resonance; contribute to the development of a stable theme and enhance conceptualization (Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley, Reference Kuyken, Padesky and Dudley2009; Padesky and Mooney, Reference Padesky and Mooney2012); access deep knowledge structures (Goncalves and Craine, Reference Goncalves and Craine1990); serve as an explanatory device (Alford and Beck, Reference Alford and Beck1997); assist engagement; provide a rationale, express emotion and transform meaning (Stott et al., Reference Stott, Mansell, Salkovskis, Lavender and Cartwright-Hatton2010); and aid memory (Martin, Cummings and Hallberg, Reference Martin, Cummings and Hallberg1992; Shell, Reference Shell1986). Within third wave cognitive therapies, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy emphasizes therapist-initiated metaphors (Stoddard and Afari, Reference Stoddard and Afari2014), as does Dialectical Behaviour Therapy (Linehan, Reference Linehan1993). However, despite the growing popularity of metaphor in CBT, the extent and manner of metaphor use is not known.

Empirical study of the effects of metaphors in psychotherapy has been based on a small number of psychotherapy sessions (Barlow, Kerlin and Pollio, Reference Barlow, Kerlin and Pollio1971; Pollio and Barlow, Reference Pollio and Barlow1975). This research has been hampered by the absence both of agreed upon definitions of metaphor and of explicit and rigorous methods of identification, especially in relation to conversational data rather than de-contextualized sentences or made-up examples. Moreover, there are many definitions in the literature, leading Soskice (Reference Soskice1985, p.15) to comment that “anyone who has grappled with the problem of metaphor will appreciate the pragmatism of those who proceed to discuss it without giving any definition at all.” The difficulties of metaphor identification are well documented (Cameron, Reference Cameron, Cameron and Low1999, Reference Cameron2003). Recently, linguists such as Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, Kaal, Krennmayr and Pasma (Reference Steen, Dorst, Herrmann, Kaal and Krennmayr2010) and Cameron and Maslen (Reference Cameron and Maslen2010) have developed more detailed methods of metaphor identification based on the work of the Pragglejaz Group (2007).

Conceptual Metaphor Theory (CMT, Lakoff, Reference Lakoff and Ortony1993) is the dominant approach to metaphor definition and identification, but is criticised for being more concerned with metaphor at the conceptual level across speech communities, rather than the complex dynamics of real-world language use by individuals (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Maslen, Todd, Maule, Stratton and Stanley2009). Conceptual metaphors (such as LOVE IS A JOURNEY) are viewed by CMT as static mappings between topic and vehicle, whereas in real discourse events, even when speakers make reference to conceptual metaphors, each speaker will have developed an idiosyncratic understanding based on different experiences (Cameron, Reference Cameron, Zanotto, Cameron and Cavalcanti2008b).

Discourse Dynamics (Cameron and Maslen, Reference Cameron and Maslen2010) is an alternative model to CMT, with potential for investigating therapeutic conversations. Based on dynamic systems theory from the physical sciences literature (Aihara and Suzuki, Reference Aihara and Suzuki2010), it sees language (including metaphorical language) as a complex, self-organizing system that unfolds fluidly over time, influenced by individual, cultural, contextual factors, present bodily states, previous conversations, goals and motivations (Cameron, Reference Cameron, Zanotto, Cameron and Cavalcanti2008b). Metaphor is seen as a tool to uncover people's ideas, attitudes and values, a view compatible with the CBT model.

Discourse Dynamics was developed for face-to-face discourse as opposed to written texts or speeches, making it suitable for investigating therapeutic interactions. In the CMT deductive approach, the coders assume a set of conceptual metaphors and search for related linguistic expressions in a set of materials, which may result in missing many metaphors actually occurring in discourse (Steen, Dorst, Herrmann, Kaal and Krennmayr, Reference Steen, Dorst, Herrmann, Kaal and Krennmayr2010). In contrast, Discourse Dynamics is inductive, moving from identified metaphors to a set of “systematic metaphors” that are not necessarily identical to conceptual metaphors and may have idiosyncratic meaning for the speaker. Details of the metaphor identification procedure are described in the method section.

Discourse Dynamics has been described as currently the most clear, operationalized, comprehensive method of metaphor identification in spoken language (Cameron, Reference Cameron2007; Cameron and Deignan, Reference Cameron and Deignan2006), and rather than just lexical units, it includes metaphorical phrases (e.g. I am “in a torrent and struggling to get a grip on the side”), which clinical experience suggests regularly occur in psychotherapy. In addition, unlike CMT, Discourse Dynamics provides methods for calculating metaphor frequency, as number of metaphor vehicles per thousand words and for calculating reliability (Cameron, Reference Cameron and Gibbs2008a). Metaphor researchers have been urged to include frequency counts where feasible, as they are a valuable aid to interpreting overall patterns of metaphor use (Todd and Low, Reference Todd, Low, Cameron and Maslen2010).

A review of studies of metaphor frequency found that the number of linguistic metaphors used in talk of different types varied from around 20 metaphors per thousand words for college lectures to around 50 in ordinary spoken conversation and 60 in teacher talk, although what is found in the data depends heavily on what is categorized as “metaphor” by the researchers (Cameron, Reference Cameron2003, p. 57). While frequency counts provide only limited information and do not clarify anything about elements of usage such as the function or helpfulness of the metaphor, the CBT literature lacks even such basic information. This study aimed to use the Discourse Dynamics metaphor identification procedure (Cameron and Maslen, Reference Cameron and Maslen2010) to determine the frequency of metaphor use in CBT sessions by therapists and clients. In addition, the reliability and utility of this approach to identifying metaphor in CBT was explored.

Method

The verbatim transcripts analysed in this study came from a previous trial of psychotherapy for depression involving 4 therapists and 20 clients in a series of 50-minute CBT sessions (Luty et al., Reference Luty, Carter, McKenzie, Rae, Frampton and Mulder2007); because these were not collected as part of a “metaphor study”, therapist or client behaviour was not influenced. Coding all 245 therapy transcripts available was impractical due to the time required for the intensive metaphor identification process. We selected 48 transcripts (a total of 12 clients with 3 different therapists from sessions 1–4 only). One therapist was excluded because they had only seen one client and transcripts were not available for all of sessions 1–4. Another therapist had seen only 3 clients so all were included. The other transcripts were randomly selected from those clients of the other two therapists where full data sets for sessions 1-4 were available. The average age of the clients was 38.3 years (range 26–56) and 75% of clients were female.

The sessions were previously assessed as adhering to the CBT model and therapists were assessed as having at least adequate competence. Therapy was based on the treatment manuals of Aaron and Judith Beck (A. Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery, Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979; A. T. Beck, Steer and Brown, Reference Beck, Steer and Brown1987; J. Beck, Reference Beck1995).

Discourse Dynamics metaphor identification procedure

In Discourse Dynamics, words and phrases are identified that are potentially metaphorical. It is not claimed that listeners will interpret the words or phrases metaphorically, or that they are intended metaphorically. This broad definition captures obvious metaphors, novel metaphors and conventionalized metaphors that are unlikely to be interpreted metaphorically but have potential to be understood as metaphor. (Conventional metaphors are technically metaphorical, but their metaphorical character has faded over time, such as “the neck of a bottle” or “the legs of a chair” (McMullen, Reference McMullen1985)). Words or phrases are identified as metaphorical where they can be justified as somehow anomalous, incongruent or “alien” in the ongoing discourse, but can be made sense of through a transfer of meaning in context. “Incongruity” is defined as having one meaning in the context and another different meaning that is more basic in some way, usually more physical and more concrete than the contextual meaning (Pragglejaz Group, 2007).

The Discourse Dynamics metaphor identification procedure is operationalized using a 4-step procedure (adapted from the Metaphor Identification Procedure developed by the Pragglejaz Group, 2007).

-

1. The researcher familiarizes her/himself with the discourse data (i.e. reads through the whole transcript).

-

2. The researcher works through the data looking for possible metaphors (i.e. looks carefully at every word or phrase).

-

3. Each possible metaphorical word or phrase is checked for:

-

a) Its meaning in the discourse context;

-

b) The existence of another, more basic meaning;

-

c) An incongruity or contrast between these meanings, and a transfer from the basic to the contextual meaning.

-

-

4. The possible metaphor is coded as metaphorical if it satisfies both these criteria:

-

a) There is a contrast or incongruity between the meaning of the word or phrase in its discourse context and another meaning; and

-

b) There is a transfer of meaning that enables the contextual meaning to be understood in terms of basic meaning.

-

The method of deciding where a metaphor vehicle begins and ends is to start from the most clearly incongruous word and work outwards, including words that also have a more basic meaning or tend to be used together (collocate). Thus the phrase “flaw in the system” is identified as one metaphor vehicle on the basis that this is a single phrase, rather than two metaphors as in: “flaw in the system” (Cameron and Maslen, Reference Cameron and Maslen2010, pp.108–110).

Personification is identified as metaphorical and occurs when something inanimate is described as if possessing life, such as “The river is moving sluggishly”. Similes are only identified as metaphorical if there is an alien metaphorical term (such as “he is like a volcano”); a direct comparison (e.g. “She is like her sister”) is not metaphorical. Very common verbs and nouns such as: make, do, give, have, get, put, thing, part and way arguably have basic meanings e.g. “thing” is a concrete object. “Have”, “do” and “get” are omitted but the others are included in the identification stage. Prepositions such as into, over, from, on, in, up, down, within, between, out of, through and behind have a basic spatial meaning and are thus included.

Coding process

Coding involved making multiple decisions, which were carefully recorded in project notes, allowing future researchers to use the same approach (available on request from FM). A corpus based dictionary (Collins Cobuild Advanced Dictionary of English, (National Geographic Learning, 2013) was used to check basic meanings and phrasal verbs (such as “get from”), as recommended by Cameron (Reference Cameron, Cameron and Low1999).

Therapy sessions 1–4 were coded because research suggests that considerable therapeutic gains can occur in early therapy sessions, with diminishing returns at higher doses (Foster, Reference Foster2011; Harnett, O'Donovan and Lambert, Reference Harnett, O'Donovan and Lambert2010; Illardi and Craighead, Reference Illardi and Craighead1994). An iterative approach was taken to coding: First, using the Discourse Dynamics approach, FM (a clinical psychologist) independently coded 12 transcripts and discussed issues arising with MS (a linguist). FM and MS then jointly coded samples of six randomly selected transcripts, to establish a shared understanding. This comprised 8 hours of coding and discussion over 3 months. Inclusion and exclusion decisions were carefully documented. FM then coded 48 transcripts making at least 3 passes over each transcript (Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, et al., Reference Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, Kaal, Krennmayr and Pasma2010). Further words and phrases for which coding was uncertain were noted and discussed with MS, and inclusion/exclusion decisions were documented. Coding was done in half hour chunks to reduce errors from fatigue. Automatic word searches were conducted for the prepositions into, over, from, on, in, up, down, within, between, out of, through and behind and other common words deemed metaphorical “homework” (like school) and “goal” (like sporting goal). A final consistency check was performed by FM.

Frequency calculation

The frequency of metaphoric words or phrases per 1000 words was calculated (Cameron, Reference Cameron and Gibbs2008a). Speaker identification and other non-speech characters were deducted from the word counts. Identified metaphoric words or phrases were exported to Excel using a specially developed computer programme, called “discombobulator” (available on request from FM). The programme extracted identified metaphors within “elementary discourse units” (van der Vliet, Bouma and Redeker, Reference van der Vliet, Bouma and Redeker2013), which were used as an alternative to Cameron's (2010) “intonation units”, (described as “idea units”). Elementary Discourse Units were used because the transcripts were not transcribed into intonation units and the audio recordings were not available. Headings were: “turn number”, “speaker” (client or therapist) and “metaphor”, to enable frequency calculations.

Reliability

A rate of inter-rater agreement in identifying metaphor of around 75% is usually considered acceptable (Cameron, Reference Cameron2003). We aimed for at least 75%, allowing some flexibility in where the metaphor vehicle began and ended. Density calculations are based on the number of vehicles per thousand words, so the indeterminacy of beginnings and endings is not usually an issue (Cameron et al., Reference Cameron, Maslen, Todd, Maule, Stratton and Stanley2009). Ten percent of transcripts (five randomly selected transcripts) were independently coded by another experienced linguist (JH), to ensure the coding was free from bias or manipulation. The independent coder was trained in the Metaphor Identification Criteria over an hour-long session. Samples of coded transcripts were provided along with an explanation of common CBT techniques and articles by Cameron and Maslen (Reference Cameron and Maslen2010).

Inter-rater agreement was calculated for: the extent to which JH agreed with FM's coding; the extent to which FM agreed with JH's coding; and the overall frequency of metaphors identified by both raters as a simple proxy for agreement.

Results

Frequency

Figure 1 shows the frequency of metaphors used by therapists and clients over four sessions. Therapists produced metaphors at approximately twice the rate of clients. The therapist frequency was 21.2 (range: 7–36) versus client frequency of 10.3 (range: 3–24) per thousand words. Therapists produced more metaphors than clients in 46 out of the 48 individual sessions. The total number of words in the sessions analysed was 352,256.

Figure 1. Metaphor frequency by therapist/client dyad.

Figure 2 shows the total metaphor frequency per thousand words in each dyad (i.e. therapist-client pair) over four sessions. Total metaphor frequency was 31.5 metaphors per thousand words. A paired t-test was conducted on the 12 therapist-client dyads to compare the rate of metaphor usage between clients and therapists. There was a significant difference in the frequencies for therapists (M = 21.2, SD = 4.7) and clients (M = 10.3, SD = 4.4); t(11) = 6.2, p < .001, which suggests that therapists used metaphors at a significantly higher frequency than clients. There was considerable variation between therapy dyads (range: 17–49).

Figure 2. Overall metaphor frequency by dyad.

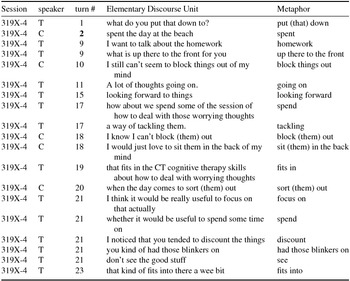

Table 1 provides a sample of what was produced after metaphors were identified and exported to Excel. The letters “T” or “C” indicate whether the therapist or client was speaking; “turn” means the complete utterance by the speaker; elementary discourse unit is the idea unit containing the metaphor vehicle; and the identified metaphor vehicle is in the right hand column. Common, conventional metaphors, such as “homework” and “see” are evident, along with novel metaphors such as “tackling” and “having blinkers on”.

Table 1. A sample of identified metaphors

Reliability

Across the five independently coded sessions, the two raters identified the same metaphors 70.2% of the time. FM identified 17.4% of metaphors that JH did not identify; while JH identified 12.4% that FM did not identify. FM found a frequency of 36.8 metaphors per thousand words in the five sessions coded, while JH found a frequency of 34.7 metaphors per thousand words, suggesting the raters were identifying metaphors at a similar frequency.

Discussion

This study aimed to determine the frequency of metaphor use by therapists and clients. We also evaluated the utility and reliability of the Discourse Dynamics method of identifying metaphors in CBT sessions. Ongoing conversations have been described as an unruly “jungle” by Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, et al. (Reference Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, Kaal, Krennmayr and Pasma2010). We found that identifying and “nailing down” metaphors reliably in this jungle was challenging but possible.

The frequency of 31.5 per thousand words (range: 17–49) in our sample of the first four therapy sessions of adults with depression was similar to that found in other studies. Cameron (Reference Cameron2003) found 27 metaphors per thousand words in conversations in an educational setting, using the Discourse Dynamics approach and Ferrara (Reference Ferrara1994) found 30 words per thousand in a single hour of psychotherapy, although her identification process was not clearly specified.

Therapists used metaphors at a much higher frequency than clients; however, the reason for this is unclear. Therapists may have a number of “stock” metaphors they use. Highly conventionalized CBT terms such as “goals” and “homework” may have contributed to higher therapist frequency counts and seem unlikely to have been deliberately used as metaphors. CBT is an active therapy with an emphasis on psycho-education and skill development, which results in therapists using teaching analogies. On the other hand, previous researchers have argued that use of a similar frequency of metaphors by clients and therapists is an indicator of collaboration (Hill and Regan, Reference Hill and Regan1991). It is possible that the marked difference in frequency found in this sample may be related to this study's focus on the first four therapy sessions, in which therapists may be relatively more active.

We found an adequate level of reliability (70.2% agreement between coders). The extent of agreement may have been decreased by the independent coder's limited knowledge of CBT processes, and limited duration of metaphor-specific training. Reliability may be increased by having all transcripts initially coded by more than one coder (Cameron and Maslen, Reference Cameron and Maslen2010).

The Discourse Dynamics identification approach proved to be broad, capturing many commonly used, conventionalized expressions, which may not be intended to have metaphorical meaning (for example “It sounds like” and “I see what you mean”). However, it is not possible to know before carrying out the analysis which metaphors may contribute to emergent themes across the conversation, and therefore a broad approach is needed (Cameron and Maslen, Reference Cameron and Maslen2010).

Challenges in coding using the Discourse Dynamics approach included instances where therapy dyads embarked on extended “literalizations”: for example, a long conversation about learning to drive in the city versus the country, to illustrate the difficulty in establishing new patterns of behaviour. These literalizations might start off as an analogy (e.g. “changing behaviour is like learning to drive a car: it becomes more automatic with practice”), which was coded as metaphorical, but extension of the metaphor into a literal discussion (e.g. of “driving” itself) without clear transfer of meaning to a topic domain was not coded as metaphorical. This approach may have reduced frequency counts. These and other coding challenges were discussed and decisions recorded.

Conversely, highly conventionalized metaphor vehicles such as a “short time” do not stand out initially as incongruous or alien, and are easy to miss. Moreover, incongruity is subjective, depending on the coders’ approach and perspective. Decisions were therefore not always clear cut. These coding issues highlight the complexity of metaphor use in real life interactions, and the inherent limitations of attempts to quantify such a complex interactional and linguistic phenomenon. Coding and counting can only ever be one part of an ongoing investigation of how metaphors are used in naturally occurring conversations, including CBT therapy sessions.

The identification approach has been described as “reliable and relatively easy to acquire” (Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, et al., Reference Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, Kaal, Krennmayr and Pasma2010, p. 165). Although this may be a reasonable assumption for a linguist, the approach proved challenging for a non-linguist to acquire and only adequate reliability was achieved. Metaphor identification using this approach is an acquired skill, even with clearly specified criteria. Supervision by a linguist is essential for a non-linguist using the Discourse Dynamics approach as is a thorough reading of (Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, et al., Reference Steen, Dorst, Berenike Herrman, Kaal, Krennmayr and Pasma2010) and (Cameron and Maslen, Reference Cameron and Maslen2010).

Some caution is needed when interpreting the results of this study. Only three therapists’ transcripts (with12 clients) were used and it is possible the rate of therapist metaphors was influenced by idiosyncratic therapist communication styles (meaning the findings may not be representative). The raw data were from a 2007 study and so may not fully reflect current metaphor use or awareness by CBT therapists following the publication of recent books and texts e.g. (Blenkiron, Reference Blenkiron2010; Stott et al., Reference Stott, Mansell, Salkovskis, Lavender and Cartwright-Hatton2010). However any such change is unlikely to be large. Finally, reliance on written transcripts meant prosodic features and gestures were unavailable for analysis, and there were some unclear passages and omissions due to sound quality. Consequently, we took a cautious approach to identification, which may have reduced the frequency of metaphors identified.

Our aim was to describe the frequency of metaphor use. No assumptions were made that the metaphors identified were necessarily productive, deliberate, helpful, or processed metaphorically by the speaker. Nor does this study tell us anything about the functions of the metaphors used. A more detailed qualitative discourse analysis is required to answer these questions.

There may not be a clear line between metaphorical and non-metaphorical language due to words and phrases gradually becoming conventionalized expressions with little or no metaphoric meaning such as the “leg” of a chair. “The reality of language in use seems to rule out the possibility of producing a precise and finite set of sufficient conditions that will delineate a classical category ‘linguistic metaphor’” (Cameron, Reference Cameron2003, p. 61). Nevertheless, it is possible that even conventional expressions captured by this approach could have mileage clinically, even when not deliberately used metaphorically e.g. slipping back into depression.

Many areas of metaphor use in CBT are ripe for future investigation, now that an adequate method for identifying metaphors is available. Possible questions include: How do therapists and clients co-construct shared metaphors? To what extent do therapists take up client metaphors and vice versa? Does working metaphorically “suit” some clients more than others? Does using the client's metaphors assist with sharing the conceptualization? If so, what impact does it have?

Because the Discourse Dynamics procedure is quite broad in its identification of metaphors, further studies will be needed to test its clinical application, particularly ways to reliably identify clients’ central metaphoric conceptualizations (described as “metaphoric kernel statements” by Witztum, van der Hart and Friedman (Reference Witztum, van der Hart and Friedman1988)). While using the Discourse Dynamics approach at times feels rather like “nailing down jelly”, it does provide a coherent underlying model and adequate reliability and as such is the most operationalized method available for identifying metaphor in future CBT research.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the CBT/IPT research group from the University of Otago Christchurch for the CBT session transcripts; Jo Hilder for the reliability check and Jayden MacRae for Discombobulator. This research was supported by a University of Otago PhD scholarship. No conflict of interest was reported.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.