Introduction

Trichotillomania is a disorder of impulse control with the essential feature of the recurrent pulling out of one's own hair, resulting in noticeable hair loss. Feelings of relief when pulling out hair is a diagnostic feature, as are feelings of tension immediately prior to hairpulling or attempts to resist urges to pull hair. It is often linked to stressful circumstances, but may also increase during periods of relaxation or boredom.

TTM may produce feelings of guilt, shame and humiliation along with strenuous efforts to avoid exposing the site of hairpulling. Behaviour may be positively reinforced by the sensory stimulation of actual hairpulling. Negative reinforcement may be a maintaining factor associated with the provision of relief from hairpulling.

A number of treatment options have been explored for TTM. On the basis of studies of treatment efficacy, Habit Reversal is considered to be one of the more successful behavioural options for the treatment of TTM, and behavioural approaches are seen as the first line treatment in non-adults (Tay, Levy and Metry, Reference Tay, Levy and Metry2004).

Qualitative descriptions of TTM suggest that hairpulling occurs in response to a range of negative affective states including boredom and anger (Mansueto, Reference Mansueto1991). TTM in children may be triggered by a psychosocial stressor such as school related problems (Oranje, Peereboom-Wynia and De Raeymaecker, Reference Oranje, Peereboom-Wynia and De Raeymaeker1986).

Case history

The present study concerned AS, a 16-year-old female who had been referred to clinical psychology for the treatment of trichotillomania. The behaviour had developed at a time of stress in AS's life, during the transition from primary to high school. Over the break, she sunburnt her scalp, causing her hair to fall out. On commencing high school, she had experienced some difficulties in peer relationships, one of the effects of which was to make her self-conscious about her appearance. As her hair began to grow back, she became troubled by the appearance of new hairs and began to pull them out. She discovered that this gave her some feelings of relief.

AS found it difficult to determine what the triggers were for her hairpulling behaviour. One trigger she was able to identify was feeling bored. She claimed that often she was in fact unaware of her hairpulling behaviour until after it had occurred. After some exploration, another major trigger was identified. This was experiencing anger, particularly as a result of conflict. At times, she explained that she would ensure that she was alone and consciously pull out hair to vent her feelings.

Anxiety and depression as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS; Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983) were both within “minimal” levels at the initial assessment. Treatment was therefore targeted towards the TTM only, although anxiety and depression levels continued to be monitored throughout treatment on a weekly basis.

Treatment took the form of Habit Reversal Training (Azrin and Nunn, Reference Azrin and Nunn1973) The approach is comprised of a number of components implemented successively in order to maximize reductions of the problem behaviour. However, AS failed to make the expected treatment gains and it became apparent that she was fundamentally unconvinced by the model. Her awareness of her behaviour remained quite low and she had difficulty in identifying high risk situations.

It was hypothesized that AS might become more accepting of the model and thus the rationale for treatment if it could be demonstrated to her. It was also felt to be useful to directly investigate the effects of emotional arousal on urges to pull, as opposed to overt hairpulling behaviour.

Design

An ABCD/DCBA reversal design was used. This allowed for the methodical confirmation that urges and behaviour changed systematically with the conditions. AS periodically verbally reported ratings of the intensity of urges to pull her hair whilst engaged in a simple writing task (describing scenes on emotions cards). The purpose of the task was to simulate conditions in which AS normally experienced urges to pull her hair, often when engaged in tasks requiring little or no thought. The neutral condition (A) served as baseline and no attempt to increase AS's emotional arousal was made before this condition. The rumination phase (B) consisted of AS listening to the emotionally arousing script, then engaging in the writing task and ruminating on the script. The cognitive distraction phase (C) was similar but, rather than ruminating, she engaged in positive self-talk about her ability to control the urges. The behavioural distraction (D) was again similar to this, but she distracted herself through texting (an ecologically valid distraction technique for AS). The intensity of the urges was compared between the conditions, along with a hairpulling substitute behaviour (touching) they provoked.

Manipulation script

This was based on an actual event described by AS and produced collaboratively. The script included affective, behavioural and physiological responses. In summary, it describes her discovery of a perceived infidelity on the part of her boyfriend and her reactions to it.

Measures

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). The HADS (Zigmond and Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983) is a brief standardized measure of present state anxiety and depression widely used in health settings.

The Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Hairpulling Scale. The MGHS (Keuthen et al., Reference Keuthen, O'Sullivan, Ricciardi, Shera, Savage, Borgmann, Jenike and Baer1995) is a self-rating scale that has been shown to demonstrate test-retest reliability, convergent and divergent validity and sensitivity to change in hairpulling symptoms. Higher scores are indicative of more severe hairpulling behaviour. This was completed at the beginning, middle and end of the experiment.

Arousal and engagement with script scales

AS was asked to rate how emotionally arousing she felt in response to hearing the script and also how able she was to engage with it. This was measured through the presentation of a Lickert-type scale (0 = not at all, 1 = slightly, 2 = medium, 3 = strong, 4 = very strong). This was completed at the middle and end of the experiment.

Intensity of urges to pull hair and frequency of substitute hairpulling behaviour

AS was asked to rate the intensity (0–10) of her urges to pull at 5 time points, at the beginning and end of the task in each condition and at three equally distributed time points throughout. During the task, AS was observed for the substitute hairpulling behaviour and a tally kept for each condition.

Results

Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale

AS scored within the “normal” range for both anxiety and depression symptoms. This was consistent with her subjective report and clinical impression.

Massachusetts General Hospital Hairpulling Scale

Scores were generally indicative of a decrease in urges to pull over time.

Arousal and engagement with script scales

AS indicated that she had consistently engaged with the script at both mid and post-experiment as “3 = strong”. Similarly, AS rated her emotional arousal following the script presentation at mid and post-experiment as “3 = strong”.

Measurement

Frequency of substitute behaviour. The behaviour was fairly infrequent, but peaked during each rumination phase (max 3), and was at its lowest during both baseline and behavioural distraction phases (one instance).

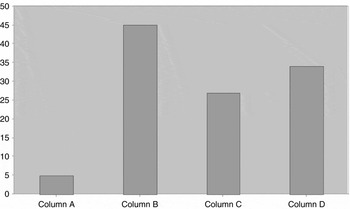

Hairpulling urge intensity. The ratings of intensity of hairpulling urges were pooled in Figure 1 to enable visual inspection of the data. The sum of the ratings for the neutral condition (A), rumination condition (B), cognitive distraction condition (C) and behavioural distraction condition (D) were 5, 45, 27 and 34 respectively. Thus AS experienced more intense urges when engaged in rumination, and of the two distraction techniques, experienced less intense urges while engaged in self-talk.

Figure 1. Pooled intensity ratings of hairpulling urges by condition, A = neutral; B = rumination; C = cognitive; D = behavioural

Discussion

The data appeared to be consistent with the main hypothesis of the experiment, demonstrating the effect of emotional arousal on urges to pull. Visual inspection indicated that engaging in the manipulation script resulted in stronger, more intense urges when compared to the baseline condition. The hairpulling substitute behaviour occurred more frequently in response to the manipulation script than in the baseline condition. As expected, rumination produced the greatest urges to pull. This is in keeping with the findings of Begotka, Woods and Wetterneck (Reference Begotka, Woods and Wetterneck2004) and the association between negative affective and “focused” hairpulling, characterizing TTM as a possible form of experiential avoidance.

However, there did not appear to be any clear difference between the intensity of the urges to pull hair during either of the two distraction conditions. Indeed the behavioural distraction phase produced slightly greater intensity of urges than the cognitive distraction phase.

There does not appear to be a clear explanation for this finding. It may be that the behavioural task (texting) was sufficient to control overt behaviour such as actual hairpulling, or in this case the substitute behaviour. However, it could be argued that it does not control the covert urges to pull hair in response to negative emotional arousal. AS did report that she was texting her friends about the content of the manipulation script. It may be that the action of texting prevented her from engaging in the behaviour, but the context of her texts increased the intensity of the urges.

The findings of this experiment highlighted to AS the impact that negative emotional arousal had on the intensity of her urges to pull, and that arousing situations acted as potential triggers for her urges and thus behaviour. In hindsight, she was able to think of the interpersonal conflicts that had often precipitated her deliberately finding herself alone and pulling her hair in a “focused” manner. Furthermore, the experiment raised AS's awareness of both her urges and overt behaviour, and demonstrated to her that there were techniques available to her that gave her at least some degree of control of her hairpulling.

The clinical implications of these findings were significant. Following a feedback session, AS reported that she was more accepting of the treatment rationale, more self-aware and, importantly, more optimistic regarding treatment. Thus the experiment served to increase her engagement. In more general clinical terms, this study serves to highlight the importance of collaboration and engagement with the therapeutic model to really bring adolescent clients on board with treatment.

Limitations of the present study and implications for future research

Criticisms may include the design omitting a neutral phase after each arousal phase, although this would have drawn out the experiment and been less acceptable to AS. Script presentation should probably have been recorded to ensure the presentation was identical each time. Criticisms can also be levelled at the degree of overlap between the phases. The writing task may also have acted as a behavioural distraction, which may have interfered with the cognitive distraction phase. Also, the behavioural distraction technique contained a cognitive element. This would have been improved by using purer techniques.

As rumination resulted in the greatest urges to pull hair, further exploration of this in TTM may prove useful, as examination of the different components of rumination and the different elements of TTM (urges, actual pulling) may help explain, for example, the results of the behavioural distraction phase of this study.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.