Introduction

Across psychotherapeutic approaches, therapist empathy has been identified as an important nonspecific factor in treatment (Elliott, Bohart, Watson and Greenberg, Reference Elliott, Bohart, Watson and Greenberg2011; Luborsky, Singer and Luborsky, Reference Luborsky, Singer and Luborsky1975) and found to exert medium-sized but variable effects on client outcomes (Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg and Watson, Reference Watson and Cain2002; Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Bohart, Watson and Greenberg2011). Definitions of therapist empathy have varied (Bohart and Greenberg, Reference Bohart, Greenberg, Bohart and Greenberg1997), though they generally have emphasized the therapist's ability to understand the client's experience and communicate this understanding to the client (Rogers, Reference Rogers1957; Truax and Carkhuff, Reference Truax and Carkhuff1967). The expression of therapist empathy within sessions is considered a complex process (Bohart et al., Reference Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg, Watson and Norcross2002; Greenberg and Rushanski-Rosenberg, Reference Greenberg, Rushanski-Rosenberg, Watson, Goldman and Warner2002) comprised of several components: affective (relating and responding to the client's emotions with similar emotions); cognitive (the intellectual understanding of client experiences; Duan and Hill, Reference Duan and Hill1996; Gladstein, Reference Gladstein1983); and attitudinal as demonstrated by warmth and acceptance (Greenberg and Rushanski-Rosenberg, Reference Greenberg, Rushanski-Rosenberg, Watson, Goldman and Warner2002). Other components include the ability to set aside one's own views to enter the client's world without judgment or prejudice (Rogers, Reference Rogers1975), and attunement to momentary changes in the client's presentation, meaning, or concerns (Thwaites and Bennett-Levy, Reference Thwaites and Bennett-Levy2007; Watson, Reference Watson and Cain2002; Watson and Prosser, Reference Watson, Prosser, Watson, Goldman and Warner2002).

A review of behavioral correlates of therapist empathy suggests that therapists may demonstrate empathy in session in several ways, including: 1) communicating with an interested, concerned, expressive tone of voice; 2) demonstrating a level of emotional intensity similar to the client's; and 3) reflecting clients’ statements, nuances in meaning, or unsaid but implied meanings back to them (Watson, Reference Watson and Cain2002). While often considered an interactional process between therapist and client (Barrett-Lennard, Reference Barrett-Lennard1981), therapist empathy seems to vary more between therapists than to fluctuate within therapists across the clients they treat (Truax et al., Reference Truax, Wargo, Frank, Imber, Battle and Hoehn-Saric1966). Therefore, most discussions of therapist empathy have focused on therapists’ behaviors and experiences rather than their clients’ reactions to the therapists per se.

Therapist empathy assessment methods include therapist self-report ratings (Barrett-Lennard, Reference Barrett-Lennard1962; King and Holosko, Reference King and Holosko2011), client ratings (Barrett-Lennard, Reference Barrett-Lennard1962; Mercer, Maxwell, Heaney and Watt, Reference Mercer, Maxwell, Heaney and Watt2004; Persons and Burns, Reference Persons and Burns1985), written analogue tasks (Miller, Hedrick and Orlofsky, Reference Miller, Hedrick and Orlofsky1991), and observer ratings (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Filipovich, Harrigan, Gaynor, Reimschuessel and Zapadka1982; Truax and Carkhuff, Reference Truax and Carkhuff1967; Watson, Reference Watson1999). Therapist self-reports have been shown to be unreliable, with therapists over-rating their empathy as compared to client report or objective observer ratings (Barrett-Lennard, Reference Barrett-Lennard1962; Kurtz and Grummon, Reference Kurtz and Grummon1972). Further, the relationship between therapist self-rated empathy and client outcomes appears to be weak (Bohart et al., Reference Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg, Watson and Norcross2002) or absent (Barrett-Lennard, Reference Barrett-Lennard1981; Gurman, Reference Gurman1977). In client reports of therapist empathy, clients label therapist behaviors such as self-disclosure and nurturance as empathic (Bachelor, Reference Bachelor1988; Watson and Prosser, Reference Watson, Prosser, Watson, Goldman and Warner2002), reflecting therapist behaviors that may co-occur with therapist empathy but are not necessarily components of it. Written analogue assessments of therapist empathy, such as the Helpful Responses Questionnaire (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Hedrick and Orlofsky1991), may not correlate strongly with direct measures of empathic reflections in client sessions (Miller and Mount, Reference Miller and Mount2001) and are considered a less-preferred alternative to direct observational assessment (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Hedrick and Orlofsky1991).

Some observer therapist empathy rating scales exist, such as the Response Empathy Rating Scale (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Filipovich, Harrigan, Gaynor, Reimschuessel and Zapadka1982) and the Accurate Empathy Scale (Truax and Carkhuff, Reference Truax and Carkhuff1967). These scales offer the advantage of providing objective and reliable information useful for psychotherapy process-outcomes research or supervisory feedback (Elliot et al., Reference Elliott, Bohart, Watson and Greenberg2011). However, Watson and Prosser (Reference Watson, Prosser, Watson, Goldman and Warner2002) note limitations of these measures: they reflect only some components of therapist empathy (e.g. Truax and Carkhuff, Reference Truax and Carkhuff1967), include assessment of client responses rather than focusing solely on therapist behavior (e.g. Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Filipovich, Harrigan, Gaynor, Reimschuessel and Zapadka1982), or assess nonverbal behaviors that limit their application to videotaped or directly observed therapy sessions (e.g. Watson, Reference Watson1999). Independent treatment integrity rating scales, such as the Cognitive Therapy Adherence and Competence Scale (Barber, Liese and Abrams, Reference Barber, Liese and Abrams2003) or the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity Scale (Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson and Miller, Reference Moyers, Martin, Manuel, Hendrickson and Miller2005), often include a single item providing a global rating of therapist empathy. Single rating therapist empathy scales may not fully capture all the components of empathy (i.e. cognitive, affective, attitudinal, attunement) and are not likely to be used to examine therapist empathy across different therapy protocols in that these scales have been tied to a particular therapy approach.

Watson (Reference Watson1999) identified several observable therapist behaviors indicative of empathy and developed an observer-rated Measure of Expressed Empathy scale that included overlapping components of therapist empathy across its nine items: therapist's concern for the client, expressivity of voice, capturing the intensity of client feelings, warmth, attunement to the client's inner world, communicating an understanding of the client's meanings or cognitive framework, communicating understanding of the client's feelings and inner experiences, responsiveness to the client, and looking concerned in facial expression or body posture. These items were construed as collectively capturing the higher-order category of therapist empathy in that they conceptually overlapped with one another (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Bohart, Watson and Greenberg2011). Intra-class correlation coefficients calculated on a sample of 16 rated client sessions indicated fair to excellent inter-rater reliability (.51 to .85; Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994). A total scale score showed a significant correlation between observer-rated therapist empathy and client ratings of therapist empathy (n = 15, r = 0.66, p < .01; Watson, Reference Watson1999). Despite its promise as an observer rating scale assessing multiple components of therapist empathy, the Measure of Expressed Empathy scale is limited by its initial testing on a small sample of client sessions, absence of factor analysis to support its purported single factor, and applicability to videotaped client sessions only.

In this report we present the development of an observer-rated adaptation of Watson's (Reference Watson and Geller1999) Measure of Expressed Empathy, called the Therapist Empathy Scale (TES), to assess the observable and overlapping cognitive, affective, attitudinal, and attunement aspects of therapist empathy in audiotaped, rather than videotaped, psychotherapy sessions. Like the Measure of Expressed Empathy scale, the TES was designed to be used across different psychotherapy protocols or approaches, akin to broad based treatment integrity rating systems such as the Yale Adherence and Competence Scale used to capture the proficiency in which therapists deliver a variety of psychotherapeutic approaches (Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Nich, Sifry, Frankforter, Nuro and Ball2000). Data to evaluate the TES are taken from a study on training therapists in motivational interviewing (MI), a person-centered, empirically supported psychotherapy designed to help enhance motivation for change (Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson and Burke, Reference Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson and Burke2010; Miller and Rollnick, Reference Miller and Rollnick2012; Smedslund et al., Reference Smedslund, Berg, Hammerstrom, Steiro, Leiknes and Dahl2011). Therapists provided audiotaped sessions with substance-using clients in which the therapist used MI (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Canning-Ball, Rounsaville and Carroll2010). All sessions were independently rated for therapist MI adherence and competence using the Independent Tape Rater Scale (ITRS), a psychometrically established measure of MI integrity that captures both the fundamental person-centered or relational aspects of MI and more advanced strategic or technical aspects of MI used to directly elicit clients’ motives for change (Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Carroll, Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Carroll2008). Notably, the fundamental MI strategies (e.g. reflective listening skills) are presumably closely linked to the capacity of therapists to express empathy within MI sessions (Miller and Rose, Reference Miller and Rose2009).

We present reliability, confirmatory factor analysis, and criterion validity data for the TES. We predicted that the TES items would be reliably rated and converge to form a single factor reflecting a higher-order category of therapist empathy based on all the individually assessed components. We hypothesized that TES and the ITRS-derived fundamental and advanced MI strategy scores would be positively associated, with larger magnitudes of association occurring between therapist empathy and fundamental MI strategy scores than advanced MI strategy scores. In addition, we expected TES scores to show modest positive correlations to scores derived from an alternative established measure of therapist empathy, the Helpful Response Questionnaire (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Hedrick and Orlofsky1991). Finally, we expected therapist empathy scores to be negatively associated with an index of MI inconsistency derived from the ITRS. Because data for the TES study were taken from a clinician training study, client outcome indicators and measures of working alliance were not available.

Method

Overview of original study protocol

Details about the original study's aims, methods, and results have been published previously (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Canning-Ball, Rounsaville and Carroll2010). The study, from which these data are drawn, compared three training strategies in MI in a randomized controlled trial conducted at 12 outpatient substance abuse community treatment programs in the State of Connecticut, USA. Programs were randomized to one of three training conditions (self-study, expert-led training, or train-the-trainer). Ninety-two therapists received the training strategy to which their program had been randomly assigned (self-study = 31; expert-led = 32; train-the-trainer = 29). Assessments were conducted at baseline, after workshop training, after supervision, and at a 12-week follow-up.

Therapist adherence and competence in MI were the main outcome measures for the original study. Because this was a clinician training study, client outcome indicators and measures of working alliance were not obtained. Trained independent raters provided ratings of therapist empathy, adherence, and competence, at baseline, post-workshop, post-supervision, and a 12-week follow-up using the TES and ITRS (both described below).

Participants

Participating therapists were employed at least 20 hours per week and treated English-speaking substance-using clients. Therapists were excluded from the study if they had received recent MI supervision or workshop training. All study procedures were reviewed and approved by the Yale University School of Medicine Human Investigation Committee, and all therapists provided written informed consent. Of therapists who consented to participate in the study, 91 (99%) provided at least one client session for analysis. Therapists were primarily female (65%) and Caucasian (82%), and most held a master's degree (54%) or bachelor's degree (23%). Therapists had been employed at their program for a mean of 4.75 years (SD = 4.01) and had received little previous MI training (mean hours = 0.92, SD = 2.79).

Measures

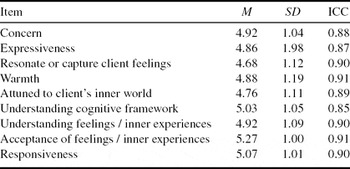

Therapist Empathy Scale (TES). This rating scale was adapted from the Measure of Expressed Empathy (MEE; Watson, Reference Watson1999). Items from the MEE were re-written to refer only to therapist speech and tone of voice, behaviors that could be assessed from an audiotape. One MEE item referring to the therapist looking concerned was eliminated, as this could not be assessed in audiotaped samples. It was replaced by an item that evaluated the extent to which the therapist's communicated nonjudgmental acceptance of the client's feelings or inner experiences, consistent with several definitions of empathy (Greenberg and Rushanski-Rosenberg, Reference Greenberg, Rushanski-Rosenberg, Watson, Goldman and Warner2002; Rogers, Reference Rogers1975). The nine TES items and their descriptions are listed in Table 1. In contrast to the 9-point MEE rating scale, TES items are rated on a 7-point Likert-type scale to be consistent with the ITRS rating system described below, with lower values indicating the absence of the targeted component of empathy and higher values indicating frequent or extensive demonstration of it (1 = not at all, to 7 = extensively).

Table 1. Therapist Empathy Scale rating item descriptions and empathy component

Independent Tape Rater Scale (ITRS; Ball, Martino, Corvino, Morgenstern and Carroll, Reference Ball, Martino, Corvino, Morgenstern and Carroll2002) is a reliable and valid measure (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Carroll2008; Santa Ana et al., Reference Santa Ana, Carroll, Añez, Paris, Ball and Nich2009; Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Carroll, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Martino2010) that assesses adherence and competence in MI as well as strategies inconsistent with MI. It has been used in several large multi-site effectiveness trials (Ball et al., Reference Ball, Martino, Nich, Frankforter, Van Horn and Crits-Christoph2007; Carroll et al., Reference Carroll, Ball, Nich, Martino, Frankforter and Farentinos2006, Reference Carroll, Martino, Suarez-Morales, Ball, Miller and Añez2009) and the original clinician training trial upon which this study is based (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Canning-Ball, Rounsaville and Carroll2010). Raters use a 7-point Likert-type scale to reflect the frequency or extensiveness of each MI strategy (adherence: 1 = not at all, to 7 = extensively) and the skill or competence with which the strategy is deployed (competence: 1 = very poor, to 7 = excellent). A prior confirmatory factor analysis of ITRS supported a two-factor solution (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Carroll2008) for the sum total of MI consistent items, representing the mean scores for five fundamental MI strategies (e.g. reflection) and five advanced MI strategies (e.g. heightening discrepancy between substance use and goals, values, or self-perceptions; Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Carroll2008). The mean adherence score for five MI-inconsistent items (e.g. unsolicited advice, direct confrontation) is also calculated, though confirmation of this “factor” was not possible because of the items’ infrequency in sessions across prior studies (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Carroll2008; Santa Ana et al., Reference Santa Ana, Carroll, Añez, Paris, Ball and Nich2009; Gibbons et al., Reference Gibbons, Carroll, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Martino2010). Intraclass correlation coefficients (Shrout and Fleiss, Reference Shrout and Fleiss1979) in the original study were good to excellent for the MI factors: fundamental MI adherence = .88; advanced MI adherence = .87; fundamental MI competence = .87, advanced MI competence = .68; MI-inconsistent adherence = .91 (Martino et al., 2011).

Independent tape rater training. Twelve raters were trained to rate the audiotaped sessions using the ITRS and TES. All raters were blinded to study training condition, assessment point, and program. Raters attended seminars to learn how to rate ITRS and TES items and then rated an identical set of 18 calibration tapes selected randomly from the larger pool of study tapes, which were used to evaluate ITRS and TES item inter-rater reliability (see Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Frankforter and Carroll2008 for detailed ITRS reliability findings).

Helpful Responses Questionnaire (HRQ; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Hedrick and Orlofsky1991) was used as an alternate form of therapist empathy assessment. This written questionnaire presents six hypothetical client statements and asks the therapist to write what he or she would say in response to each client statement. Responses are scored on a five-point ordinal scale indicating the depth of reflection, using concepts from the Accurate Empathy Scale (Truax and Carkhuff, Reference Truax and Carkhuff1967) and Gordon's (Reference Gordon1970) description of active listening. A total score is obtained by summing the reflective depth scores for all six items (range = 6 to 30), with higher scores indicating greater demonstration of therapist empathy. Four raters were trained to score the HRQ; these raters did not rate sessions using the ITRS or TES. Raters were blinded to study training condition, assessment point, and program. Raters attended a 4-hour seminar to learn the HRQ scale and then rated an identical sample of 40 randomly selected protocol HRQs. Inter-rater reliability for HRQ reflective depth scores was excellent (ICC = .95).

Statistical analyses

Reliability. We calculated TES scale item reliability using (Shrout and Fleiss, Reference Shrout and Fleiss1979) two-way mixed model (3.1) intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs), with item ratings as the random effect and raters as the fixed effect. Cronbach's alpha was also calculated.

Construct validity. First, we screened data to determine whether the sample could be combined over assessment time points and therapist training conditions, using three-level intercept-only mixed-effects regression models (level 1: repeated measures, level 2: therapist, level 3: training condition) with intercept entered as fixed and other factors as random (Tabachnick and Fidell, Reference Tabachnick and Fidell2007). Larger intraclass correlations for level 2 or level 3 factors would indicate a significant proportion of the variability in empathy score was related to differences between participants or training conditions as compared to variability within either factor.

To test for the scale's hypothesized single construct of therapist empathy, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis using structural equation models with AMOS (6.0) software (Arbuckle, Reference Arbuckle2005) and full information maximum likelihood estimation. Several indices were used to determine model fit (Marsh, Balla and McDonald, Reference Marsh, Balla and McDonald1988; Yadama and Pandey, Reference Yadama and Pandey1995): nonsignificant (p > .05) chi-square goodness-of-fit index, χ2 / degree of freedom ratio < 2, normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI) and comparative fit index (CFI) > .90, and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) < .10. Because confirmatory factor analysis solution propriety is affected by sample size (Gagne and Hancock, Reference Gagne and Hancock2006; Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Balla and McDonald1988; Yadama and Pandey, Reference Yadama and Pandey1995), we relied on the preponderance of evidence to determine whether to accept the single factor model. To provide multiple opportunities to examine factor structure in our repeated measures data and to account for concerns related to sample size, models were run separately at each time point as well as for all time points combined.

Criterion validity. To estimate criterion validity, we calculated correlations between therapist empathy and ITRS factors representing fundamental and advanced MI adherence and competence, as well as HRQ scores to see the degree to which these scores converged. We also examined the correlations between therapist empathy and MI-inconsistent behavior to see if the scores would diverge as predicted.

Results

Data screening

This study contains data at each of four assessment time points from therapists who submitted an audiotaped client session. Retention rates in the original training study were good, and recorded client sessions were provided by 88–95% of therapists at each assessment point, with variation due to therapist compliance, recording operator error, and equipment failure. Sample sizes across time points are: baseline = 87; post-workshop = 84; post-supervision = 78; 12-week follow-up = 66, with a combined total = 315 client sessions. TES and other data were screened for normality and linearity. On the TES items, eight multivariate outliers were found in the total sample. Analyses were run with and without these outliers. No interpretive differences emerged. Therefore, results are presented for the full sample.

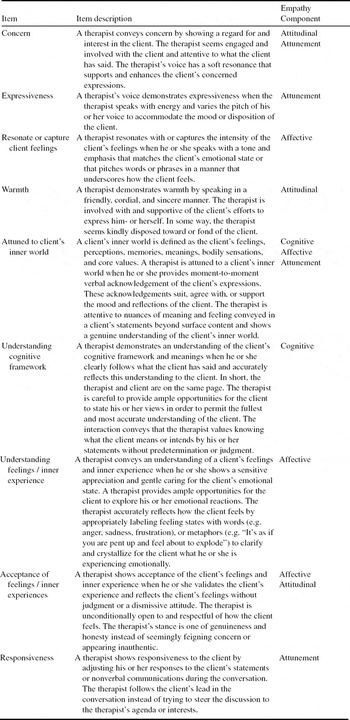

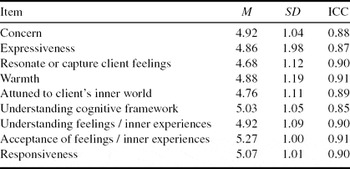

TES reliability

Descriptive statistics for the entire sample and ICC reliability estimates for each of the TES items are presented in Table 2. Guidelines suggest that ICCs below .40 are considered poor, .40 to .59 are fair, .60 to .74 are good, and .75 or above are considered excellent (Cicchetti, Reference Cicchetti1994). Using the sample of 18 reliability tapes rated by all raters, ICCs for all TES items were in the excellent range. The mean total TES score across therapists and assessment time points was 4.93 (SD = 0.89), reflecting “quite a bit” of expressed empathy. Cronbach's alpha among the 9 items was .94, indicating high scale reliability between items.

Table 2. Therapist Empathy Scale rating items: means, standard deviations, and intra-class correlation coefficient reliabilities

Notes: N = 315. Ratings are on a 7-point Likert scale: 1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = infrequently, 4 = somewhat, 5 = quite a bit, 6 = considerably, 7 = extensively

Intra-class correlations were calculated from the random-effects regression model for therapist (ρ = .078) and training condition (ρ = .019), indicating that 7.8% of the variance in empathy scores was related to differences between therapists as compared to differences within therapists, training conditions, and over time, while only 1.9% variance in empathy was related to differences between training conditions as compared to differences within training conditions, therapists, and over time. Based on this finding, and to accommodate the repeated-measures nature of the available data, we present factor analyses and correlations separately at each time point as well as combined across time points. As only a small portion of variance was attributable to differences between training conditions, we do not present findings separated by therapist training condition.

TES factor structure

Table 3 presents fit indices from confirmatory factor analyses of our predicted one-factor model for client sessions at each assessment time point separately and combined across all assessment time points. The hypothesized single factor model demonstrated a good fit at all assessment time points using NFI, IFI, and CFI, with the exception of NFI just below criterion at the post-workshop assessment point. Chi-squares, chi-square degrees of freedom ratios, and RMSEA were indicative of model fit at 12-week follow-up but less so at other time points or for the sample overall. Based on the reasonable fit obtained in these analyses, we calculated mean TES scores from the nine items for each rated session to represent the construct of therapist empathy.

Table 3. Fit indices for model of Therapist Empathy Scale

Notes: The goodness-of-fit of the predicted one-factor latent structure is determined by evidence from several indices suggesting a well fitted model. Fit indices used include a nonsignificant chi-square, chi-square degrees of freedom ratios < 2, normed fit index (NFI), incremental fit index (IFI) and comparative fit index (CFI) > .90, and the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) ≤ .10 degrees of freedom (Marsh et al., Reference Marsh, Balla and McDonald1988; Yadama and Pandey, Reference Yadama and Pandey1995). Statistics meeting these criteria are bolded.

Criterion validity

Table 4 displays correlation coefficients between TES scores and fundamental and advanced MI strategy adherence and competence and MI-inconsistent adherence scores. As expected, fundamental adherence and competence in MI showed large significant correlations with TES scores (range = .50 to .69) for the overall sample and at each time point. TES scores were also significantly correlated with advanced MI adherence and competence (range = .27 to .51), although the magnitude of associations was less than those found for fundamental MI strategies. Correlations between TES and HRQ scores were small (r = .14) for the entire sample and non-significant at each assessment time point. Finally, correlations between therapist empathy and MI-inconsistent behavior scores were non-significant with the exception of a negative correlation at the 12-week follow-up assessment time point (r = −.33).

Table 4. Correlations among Therapist Empathy Scale and MI Adherence and Competence, HRQ, and MI-Inconsistent Behavior

Notes: Fund. = Fundamental. Adv. = Advanced. HRQ = Helpful Responses Questionnaire.

* significant at p< .05, ** significant at p < .01. N for competence may be less than listed.

Discussion

This study examined the initial psychometric properties of the TES, an independent observer rating scale of therapist empathy adapted from Watson's (Reference Watson and Geller1999) MEE. The TES scale items demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability. In addition, some support for the scale's single factor structure was indicated by fit indices in confirmatory factor analyses. Comparison to the original MEE is not available as the MEE has not been subject to factor analysis. Finally, the TES showed criterion-related validity in that it converged in expected ways with indices of therapist MI adherence and competence and diverged from therapists’ MI inconsistent behaviors. Thus, the TES shows preliminary promise as a reliable and valid observer-rated therapist empathy scale assessing multiple aspects of therapist empathy in audiotaped client sessions.

The relatively good fit of a single factor model for the TES lends support to the notion that therapist empathy is a higher-order factor based on overlapping components of empathy. Elliott and colleagues (Reference Elliott, Bohart, Watson and Greenberg2011) note that some definitions of empathy focus on the development of empathic rapport through the therapist's warm, compassionate, accepting attitude; other definitions focus on the ongoing attempts to stay attuned to changes in client meaning or feeling; and still others definitions are based on the therapist's attempts to understand the client's experiences. However, these different components of empathy are not mutually exclusive and may co-occur. In this study, nine TES items assessed the degree to which the therapists were able to accurately understand and articulate their clients’ feelings and thoughts in a nonjudgmental, accepting, and genuinely concerned manner, while remaining open to changes or shifts in their clients’ experiences during the session, consistent with Watson's (Reference Watson1999) work. The high internal consistency of ratings among these items, combined with the CFA single factor findings across multiple assessment points, suggest that the components of the therapists’ empathic skills (i.e. affective, cognitive, attitudinal, attunement) coalesced such that therapists in this study were prone to express empathy across multiple component areas in similar degrees rather than to vary widely in their expression of empathy in any one area. This finding raises the question about the extent to which the 9-item TES would psychometrically outperform a shorter global empathy rating scale that attempts to tap the same construct (e.g. a 4-item scale assessing cognitive, affective, attitudinal, and attunement aspects of empathy).

Convergent validity was supported by moderate to large associations between TES scores and indices of MI adherence and competence. As predicted, TES scores were more strongly associated with fundamental MI strategies than with advanced strategies used to directly elicit clients’ motives for change, consistent with the emphasis on person-centered and empathic responding in fundamental MI skills (Miller and Rose, Reference Miller and Rose2009). Unexpectedly, correlations between TES and HRQ scores were insignificant at all four study assessment points and only a small positive correlation was obtained when data were combined across all time points. Given the strong significant associations between TES and MI integrity rating scores, this finding contributes to the literature that has emphasized the inadequacy of written analogue tasks for measuring therapist empathy (Miller and Mount, Reference Miller and Mount2001; Miller et al., Reference Miller, Hedrick and Orlofsky1991).

The TES also showed some predicted divergent validity in that the TES scores were negatively correlated with therapists’ MI-inconsistent adherence at the follow-up assessment point. However, the correlations were weaker and not significant in therapists’ MI sessions overall, at baseline, following workshop training, or after a period of post-workshop supervised practice. These findings may be due to the low frequency of MI-inconsistent behavior in this study, which resulted in a restricted range of MI-inconsistent scores (Martino et al., Reference Martino, Ball, Nich, Canning-Ball, Rounsaville and Carroll2010). Alternatively, therapist empathy and some MI-inconsistent behavior may not necessarily be incompatible. Moyers, Miller and Hendrickson (Reference Moyers, Miller and Hendrickson2005) examined therapist interpersonal skill, a latent construct including single-item observer ratings of therapist warmth and empathy, in the context of MI-inconsistent behavior. Overall, correlations between MI-inconsistent behavior and therapist interpersonal skill were negative. However, when therapists acted in MI-inconsistent ways while demonstrating high levels of warmth and empathy, they achieved the same level of in-session client involvement as in sessions without MI-inconsistent behavior and equivalent interpersonal skill. A similar phenomenon with therapists demonstrating empathy while engaging in some MI-inconsistent behavior may have diminished the strength of association between TES and MI inconsistency scores in our study.

While this study did not include client outcomes, previous studies indicate a relationship between therapist empathy and client outcomes, with medium-sized associations in meta-analyses (r = .32, Bohart et al., Reference Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg, Watson and Norcross2002; r = .31, Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Bohart, Watson and Greenberg2011) even when controlling for other client and treatment factors (Burns and Nolen-Hoeksema, Reference Burns and Nolen-Hoeksema1992). Although causality cannot be inferred, these results are consistent with Roger's (Reference Rogers1957) assertion that empathy is necessary for client change and raise questions about how therapist empathy and client outcome are linked. Therapist empathy may directly impact client outcomes or mediate them by increasing compliance with treatment, providing a corrective emotional experience, promoting cognitive-affective processing or self-healing (Bohart et al., Reference Bohart, Elliott, Greenberg, Watson and Norcross2011), or increasing client motivation (Moyers and Miller, Reference Moyers and Miller2012). Therapist empathy also may faciliate the working alliance (Ackerman and Hilsenroth, Reference Ackerman and Hilsenroth2002; Watson and Geller, Reference Watson and Geller2005), or the bond between client and therapist and their agreement about therapy tasks and goals (Bordin, Reference Bordin1979), which has been found to exert direct medium effects on client outcomes (Horvath and Bedi, Reference Horvath, Bedi and Norcross2002; Martin, Garske and Davis, Reference Martin, Garske and Davis2000; Zuroff and Blatt, Reference Zuroff and Blatt2006). Further research is needed to understand the relationships among these variables. For example, data from randomized clinical trials with multiple session-specific ratings of therapist empathy, alliance, and client outcomes in earlier and later sessions could be examined to provide some indication of temporal sequence.

This study also raises questions about the degree to which therapists can be trained to be more empathic with their clients. Presumably, extensive training and supervision in the heavily person-centered MI, as provided in the expert and train-the-trainer conditions of the original study, might have improved therapists’ empathic skills more so than in the minimal training self-study condition. Surprisingly, no such differences were evident and might be explained in several ways. First, the amount of training in the fundamental or relational skills of MI relative to advanced or technical skills to elicit motivations for change might have been inadequate to markedly improve the therapists’ empathic capacity. The appropriate dose and duration of training in both critical areas that underpin MI remains a matter of debate and research, with no firm conclusions to date (Miller and Rollnick, Reference Miller and Rollnick2012). Second, it is possible that therapist empathy may not be particularly sensitive to training efforts depending on the therapists’ pre-training foundational level of empathic skills. It may be that therapists need a minimum degree of baseline empathic capacity for them to improve their ability in this area (Moyers and Miller, Reference Moyers and Miller2012; Nerdrum and Hoglend, Reference Nerdrum and Hoglend2002). Accordingly, Miller and colleagues (Reference Miller, Moyers, Arciniega, Ernst and Forcehimes2005) used an accurate empathy screening procedure to hire therapists for a clinical trial of an intervention based on MI (Miller, Moyers, Arciniega, Ernst and Forcehimes, Reference Miller, Moyers, Arciniega, Ernst and Forcehimes2005). Taped conversations with study staff were coded for accurate empathy based on a specific criterion involving reflective listening. Only candidates that met the criterion for adequate foundational empathy skills were hired. Study authors commented that this prescreening task, although effortful, resulted in better therapist training outcomes than in training studies with unscreened therapists (Miller et al., Reference Miller, Moyers, Arciniega, Ernst and Forcehimes2005). Additional study is needed to determine the extent to which therapists can be trained to be more empathic and what factors may moderate this process.

This study has several limitations. First, the study assessed the psychometric properties of the TES in one sample of therapists using MI within a therapist training protocol. Replication of the findings with other therapists, psychotherapeutic approaches, and clinical circumstance outside a training protocol is needed. Second, the same group of raters used the same frequency and extensiveness 7-point rating method for the TES and MI adherence and competence scores. This may have inflated the observed convergent validity associations. Third, this study did not include client ratings of therapist empathy or measures of working alliance that would have allowed for examination of the sensitivity and specificity of the TES to the clients’ experience of their therapists. Fourth, this study used a written measure of therapist empathy, the HRQ, to examine convergent validity, rather than an alternate observer rating system of therapist empathy (e.g. Accurate Empathy Scale). Finally, since no client outcomes were gathered in the parent study, we were not able to determine how well the TES predicted therapeutic outcomes, a key feature in establishing the validity of any empathy measure (Elliott et al., Reference Elliott, Bohart, Watson and Greenberg2011).

Nonetheless, the results of this study indicate initial support for the reliability, construct, and criterion validity of the TES and use of the scale to examine therapist empathy in audiotaped client sessions. The TES may have utility in therapy process-outcomes studies to examine the moderating or mediating effects therapist empathy may have on client response to different types of psychotherapeutic treatments. Moreover, it may provide a useful tool for monitoring the degree of expressed empathy in sessions, giving therapists performance feedback about their empathic skills, and coaching them to improve in this important therapeutic area.

Acknowledgements

Writing of this manuscript was supported by the Office of Academic Affiliations, Advanced Fellowship in Mental Illness Research and Treatment, Department of Veterans Affairs, the Veterans Affairs Connecticut Healthcare System, and the Department of Veterans Affairs New England Mental Illness Research, Education, and Clinical Center (MIRECC). This study was funded by the US National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01 DA16970 awarded to Steve Martino, with additional support provided by R01 DA023230, U10-DA013038 and P50-DA09241). We have no financial interests to report.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.