Introduction

Anger is an emotion frequently felt by children and adolescents and is associated with various mental disorders and psychosocial problems (Roy et al., Reference Roy, Brotman and Leibenluft2019; Stringaris and Taylor, Reference Stringaris and Taylor2015). The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (5th edition) (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) describes that anger in children and adolescents could be related to various mental disorders such as disruptive mood dysregulation disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety disorders, and depressive disorders. In addition, several cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have indicated that irritability, an increased proneness to anger, was related to both internalising and externalising problems in community children and adolescents (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Schouboe, Kircanski, Leibenluft, Stringaris and Gotlib2019; Mulraney et al., Reference Mulraney, Melvin and Tonge2014). Furthermore, if children and adolescents do not express their anger properly, it could lead to various problems such as aggression and suicide (Kerr and Schneider, Reference Kerr and Schneider2008). Therefore, it is essential to conduct empirical research which allows us to identify the risk factors of anger in children and adolescents.

Beck’s cognitive distortion model explained the onset and maintenance of mental health problems such as anxiety and depression (Beck, Reference Beck1979; Beck et al., Reference Beck, Rush, Shaw and Emery1979). According to this model, mental health problems are sustained by a series of cognitive processes consisting of multiple cognitive variables (i.e. cognitive errors and automatic thoughts). Cognitive errors refer to cognitive operations that evaluate external events with faulty and negative interpretations, while automatic thoughts, or self-statements, refer to cognitive products that can be the result of cognitive operations. Various empirical studies were conducted on the cognitive variables related to internalising and externalising problems in children and adolescents (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2015; Hogendoorn et al., Reference Hogendoorn, Wolters, Vervoort, Prins, Boer, Kooij and De Haan2010; Maric et al., Reference Maric, Heyne, van Widenfelt and Westenberg2011).

Several measures were developed for identifying cognitive errors and automatic thoughts in children and adolescents. The Children’s Negative Cognitive Error Questionnaire (CNCEQ) and its revised version (Leitenberg et al., Reference Leitenberg, Yost and Carroll-Wilson1986; Maric et al., Reference Maric, Heyne, van Widenfelt and Westenberg2011) are widely used self-rating scales that measure the cognitive errors associated with anxiety and depression in children and adolescents. The CNCEQ includes four typical cognitive errors: ‘Catastrophizing’, ‘Overgeneralizing’, ‘Personalizing’ and ‘Selective abstraction’. Previous studies showed that the four cognitive errors were associated with anxiety and depression in children and adolescents (Epkins, Reference Epkins1996; Schwartz and Maric, Reference Schwartz and Maric2015; Weems et al., Reference Weems, Berman, Silverman and Saavedra2001). The Children Cognitive Distortions Questionnaire (CCDQ; Leung and Poon, Reference Leung and Poon2001) is a self-reported questionnaire used to measure cognitive errors related to anxiety, depression and aggression in Chinese children and adolescents. The study provided that the different types of cognitive errors were significantly related to anxiety, depression and aggression (Leung and Poon, Reference Leung and Poon2001). In Japan, the Children’s Cognitive Errors Scale (CCES) and Cognitive Errors Scale for Adolescents (CES-A) were developed to measure cognitive errors in children and adolescents (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2012; Ishikawa and Sakano, Reference Ishikawa and Sakano2003; Kishida and Ishikawa, Reference Kishida and Ishikawa2016). The CCES measures the same four types of cognitive errors as the CNCEQ, and the CES-A measures six types of depression-provoking cognitive errors based on Beck’s cognitive model (Beck et al., 1979). Cognitive errors measured by the CCES and CES-A were significantly related to anxiety and depressive symptoms in Japanese children and adolescents (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2012; Kishida and Ishikawa, Reference Kishida and Ishikawa2016; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Ishikawa and Arai2004).

In terms of automatic thoughts, the Children’s Automatic Thoughts Scale (CATS) and its revision are widely used self-report scales that measure automatic thoughts related to anxiety, depression and externalising problems in children and adolescents (Hogendoorn et al., Reference Hogendoorn, Wolters, Vervoort, Prins, Boer, Kooij and De Haan2010; Schniering and Rapee, Reference Schniering and Rapee2002). The CATS includes four types of negative automatic thoughts: ‘Physical threat’, ‘Social threat’, ‘Personal failure’ and ‘Hostility’. Previous studies showed that ‘Physical threat’ and ‘Social threat’ could be related to internalising disorders, such as anxiety and depression, whilst ‘Hostility’ could be related to externalising disorders, such as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder (Hogendoorn et al., Reference Hogendoorn, Wolters, Vervoort, Prins, Boer, Kooij and De Haan2010; Schniering and Rapee, Reference Schniering and Rapee2002; Schniering and Rapee, Reference Schniering and Rapee2004). In Japan, several scales were also developed to measure self-statements (Children’s Self-Statement Scale: CSSS) and automatic thoughts (Automatic Thoughts Inventory for Children: ATIC). Automatic thoughts and self-statements measured by these scales were related to anxiety and depression in Japanese children and adolescents (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2012; Ishikawa and Sakano, Reference Ishikawa and Sakano2005; Sato and Shimada, Reference Sato and Shimada2006).

Previous studies demonstrated the role of specific cognitive errors and the content-specificity hypothesis of automatic thoughts for internalising problems (e.g. anxiety and/or depression) or externalising problems (e.g. aggression) in children and adolescents. However, empirical studies between anger and anger-provoking cognitive errors and automatic thoughts in children and adolescents are lacking. As discussed above, given that anger could be related to various mental disorders rather than specific to a certain diagnosis, further research is needed to identify a cognitive specificity of anger. One of the typical cognitive errors associated with anger is hostile attribution bias (Crick & Dodge, Reference Crick and Dodge1994; de Castro et al., Reference de Castro, Veerman, Koops, Bosch and Monshouwer2002; Martinelli et al., Reference Martinelli, Ackermann, Bernhard, Freitag and Schwenck2018); it refers to the tendency to interpret others’ behaviours as having a hostile intent. Previous studies showed that children and adolescents with hostile attribution bias were more likely to exhibit aggression, especially reactive aggression (Martinelli et al., Reference Martinelli, Ackermann, Bernhard, Freitag and Schwenck2018). Reactive aggression is considered highly related to the emotion of anger (Martinelli et al., Reference Martinelli, Ackermann, Bernhard, Freitag and Schwenck2018). Therefore, hostile attributional bias might exacerbate anger theoretically. However, no empirical studies have examined the relationship between hostile attribution bias and anger using reliable and valid scales. In terms of automatic thoughts, an effect of anger-provoking self-statements for late adolescents (i.e. university students) were investigated (Masuda et al., Reference Masuda, Kanetsuki, Sekiguchi and Nedate2005). The Anger Self-Statements Questionnaire (ASSQ), which was developed for late adolescents, had a five-factor model of anger-provoking self-statements (‘Injustice by others’, ‘Hostile thoughts’, ‘Justification for revenge’, ‘Self-condemnation’ and ‘Blaming others’). The study (Masuda et al., Reference Masuda, Kanetsuki, Sekiguchi and Nedate2005) showed that trait-anger was relatively more correlated to sub-scales concerning negative thoughts about others (‘Hostile thought’, r = .38; ‘Justification for revenge’, r = .39; ‘Blaming others’, r = .41) rather than those about themselves (‘Self-condemnation’, r = .31). Additionally, physical aggression was correlated only to ‘Justification for revenge’ (r = .31), but not to ‘Blaming others’ (r = .13) and ‘Hostile thoughts’ (r = .12). Considering the results, the automatic thoughts, especially blaming and criticising other people, might be specific to anger, while those concerning justification for revenge might be aggression-specific automatic thoughts. However, the applicability of the ASSQ for children has not been confirmed and no studies have examined anger-specific automatic thoughts in children and adolescents.

The purpose of this study was to develop new questionnaires for anger-provoking cognitive errors and automatic thoughts, and to examine relationship between anger, cognitive errors and automatic thoughts in children and adolescents. First, we developed two scales. One was the Anger Children’s Cognitive Error Scale (A-CCES), which measured anger-provoking cognitive errors; the other was the Anger Children’s Automatic Thought Scale (A-CATS), which measured anger-provoking automatic thoughts. Thereafter, we examined relationships between anger, cognitive errors and automatic thoughts using a hierarchical regression analysis. Finally, using a mediation analysis, we examined the cognitive process in which cognitive errors created automatic thoughts, which provoked anger in children and adolescents.

Method

Participants and procedures

A survey was conducted by administering four questionnaires to 529 Japanese children and adolescents. We obtained informed consent from the principals of the schools where this research was conducted. Next, homeroom teachers obtained informed consent from all students who participated in this study. The study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board to which the first author belonged when the survey was conducted (approval reference 18048).

Measures

Anger Children’s Cognitive Error Scale (A-CCES)

The A-CCES is a self-report scale that measures hostility attribution bias created in this study. Children and adolescents answered seven questions on a 4-point scale (0, not at all; 1, not really; 2, somewhat; 3, very much so).

A preliminary version of the A-CCES was developed as follows. First, a community group of 94 Japanese children and adolescents (42 boys, 52 girls; average age of 12.47 years old (SD = 1.65); range 9–15 years) were asked to recall recent personal situations that provoked anger. Three graduate students, who were registered on a clinical psychology training course, reviewed and arranged the situations based on the following three points: sorting overlapping situations, excluding situations that were unlikely to happen, and excluding home-related situations. As a result, nine situations (seven friend-related situations and two teacher-related situations) were selected as situations that provoked anger in children and adolescents. Then, for each situation, an item of hostile attribution bias was created. Thus, nine items were created. Secondly, two other graduate students examined the face validity of the nine items based on the following three points: (a) meeting the definition of cognitive errors, (b) meeting the definition of hostile attribution bias, and (c) not meeting the definition of the cognitive errors associated with anxiety and depression (catastrophizing, overgeneralizing, personalizing, and selective abstraction). As a result, nine items were considered to have face validity. Finally, two university professors, who have expertise in cognitive behavioural therapy for children and adolescents, confirmed the face validity of the nine items based on the following three points: (a) whether children and adolescents could understand the items, (b) whether the item could be related to anger in children and adolescents, and (c) whether the item could not be related to anxiety or depression in children and adolescents. As a result, two items in the teacher-related situations were judged to be highly likely to provoke anxiety and depression in Japanese children and adolescents, and the two items were excluded. Based on the above procedure, a preliminary version of the Anger Children’s Cognitive Error Scale (A-CCES), which consists of the seven hypothetical situations and the seven items of hostile attribution bias, was created. The A-CCES can be available by contacting the first author.

Anger Children Automatic Thought Scale (A-CATS)

The A-CATS is a self-report scale that measures negative thoughts about others, within the last week, created in this study. Children and adolescents answered 14 items using a 4-point scale (0, never; 1, almost never; 2, sometimes; 3, often).

A preliminary version of the A-CATS was developed as follows. First, the 94 Japanese children and adolescents who participated in the preliminary study for the ACCES were asked to recall recent personal cognitions in situations that provoked anger. Three graduate students, who were registered on a clinical psychology training course, reviewed and arranged the cognitions based on the following three points: sorting overlapping situations, excluding personal scenes, and excluding items that may be inappropriate when conducting surveys in school settings (e.g. ‘he/she should die’, ‘he/she should be killed’). As a result, 39 items were selected as automatic thoughts. Secondly, two other graduate students examined the face validity of 39 items based on the following three points: (a) meeting the definition of automatic thoughts, (b) being cognitions, not emotions or actions, and (c) being cognitions about others, not about their self. As a result, 31 items were considered to have face validity. Finally, two university professors confirmed the face validity of 31 items based on the following three points: (a) whether children and adolescents could understand the items, (b) whether the item could be related to anger in children and adolescents, and (c) whether the item could not be related to anxiety or depression in children and adolescents. As a result, 17 items that were judged to be not only specific to anger, but also related to anxiety or depression were excluded. Based on the above procedure, a preliminary version of the Anger Children’s Automatic Thought Scale (A-CATS), which consisted of 14 items of negative thoughts about others, was created. The A-CATS can be available by contacting the first author.

Anger Scale for Children and Adolescents (ASCA)

The ASCA is a 7-item scale on anger (Takebe et al., Reference Takebe, Kishida, Sato, Takahashi and Sato2017), such as, ‘I am angry’ and ‘I am irritated’. Children and adolescents answered seven questions on a 4-point scale (0, not true at all; 1, slightly true; 2, mostly true; 3, very true). The reliability and validity of the ASCA were confirmed (Takebe et al., Reference Takebe, Kishida, Sato, Takahashi and Sato2017). A higher score on the ASCA indicates higher anger. The internal consistency in this study was high (α = .95).

Japanese version of Short Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale (Short CAS)

The Short CAS is an 8-item scale that measures anxiety symptoms (Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Ishii, Fukuzumi, Murayama, Ohtani, Sakaki, Suzuki and Tanaka2018; Spence et al., Reference Spence, Sawyer, Sheffield, Patton, Bond, Graetz and Kay2014). Children and adolescents answer eight questions on a 4-point scale (0, never; 1, sometimes; 2, often; 3, always). The reliability and validity of the Short CAS were confirmed (Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Ishii, Fukuzumi, Murayama, Ohtani, Sakaki, Suzuki and Tanaka2018). A higher score indicates higher anxiety symptoms. The internal consistency in this study was high (α = .87).

Statistical analyses

We examined structural validity (exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses), internal consistency and construct validity (hypotheses testing) of the A-CCES and the A-CATS. The maximum likelihood method was used for exploratory factor analyses and the diagonal weighted least squares method was used for confirmatory factor analyses. For construct validity (hypotheses testing), the following four hypotheses were set based on the previous studies (Hogendoorn et al., Reference Hogendoorn, Wolters, Vervoort, Prins, Boer, Kooij and De Haan2010; Masuda et al., Reference Masuda, Kanetsuki, Sekiguchi and Nedate2005; Schniering and Rapee, Reference Schniering and Rapee2004). Specifically, there would be (a) a positive moderate correlation (.40 – .60) between cognitive errors and anger, (b) a moderate positive moderate correlation (.40 – .60) between automatic thoughts and anger, (c) a weak positive correlation (.20 – .40) between cognitive errors and anxiety symptoms, and (d) a weak positive correlation (.20 – .40) between automatic thoughts and anxiety symptoms. Thereafter, a hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to examine the effects of cognitive errors and automatic thoughts on anger, after controlling for age and gender, as well as anxiety symptoms to partial out the effects of their correlation with anger. The ASCA score was used as the dependent variable. In the first step, age and gender was entered as an independent variable. The Short CAS score was entered in the second step, and both the A-CCES and A-CATS scores in the third step. As the final step, an interaction term for the scores of the A-CCES and A-CATS were created after centring the scores of the two scales to avoid problems of multi-collinearity. Finally, a mediation analysis was conducted to examine the cognitive process in which cognitive errors created automatic thoughts, which provoked anger in children and adolescents. The bias-corrected 95% confidence interval was calculated based on 2000 bootstrap samples. SPSS 25 was mainly used for statistical analyses and R version 3.3.3 (lavaan) for confirmatory factor analyses.

Results

Participants

After excluding questionnaires with missing or incorrect answers from the 529 Japanese children and adolescents, 485 participants (231 males, 254 females; average age 12.07 years (SD = 1.81); range 9–15 years) were analysed (response rate was 91.68%).

Structural validity and internal consistency

First, an exploratory factor analysis using the maximum likelihood method was conducted for the preliminary version of the A-CCES (Table 1). As a result, a one-factor structure of the seven items was yielded, and sufficient factor loading was shown for each item (.51 – .63). In addition, after conducting a confirmatory factor analysis using the diagonal weighted least squares method, a one-factor model was confirmed (CFI = .983, TLI = .974, RMSEA = .046 [90% CI = .020 – .070]). The internal consistency in this study was moderate (α = .76). Based on the above results, the structural validity and internal consistency of the A-CCES were confirmed. The A-CCES consists of items regarding hostile attribution bias. Accordingly, the cognitive errors assessed by the A-CCES was considered as ‘Hostile attribution bias’ conceptually.

Table 1. Results of the factor analysis of the Anger Children’s Cognitive Error Scale (n = 485)

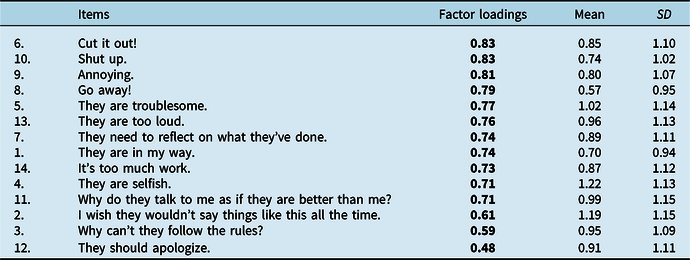

Second, an exploratory factor analysis using the maximum likelihood method was conducted for the preliminary version of the A-CATS (Table 2). As a result, a one-factor structure of the 14 items was obtained, and sufficient factor loading was shown for each item (.48 – .83). In addition, after conducting a confirmatory factor analysis using the diagonal weighted least squares method, a one-factor model was confirmed (CFI = .998, TLI = .998, RMSEA = .022 [90% CI = .000 – .035]). The internal consistency in this study was high (α = .94). Based on the above results, the structural validity and internal consistency of the A-CATS were confirmed. Items loading highly on the single factor included ‘Cut it out!’ (0.83), ‘Shut up’ (0.83) and ‘Annoying’ (0.81). These items were related to blaming and criticising other people. Therefore, the automatic thoughts assessed by the A-CATS are considered to capture ‘Blaming others’.

Table 2. Results of the factor analysis of the Anger Children’s Automatic Thought Scale (n = 485)

Descriptive statistics

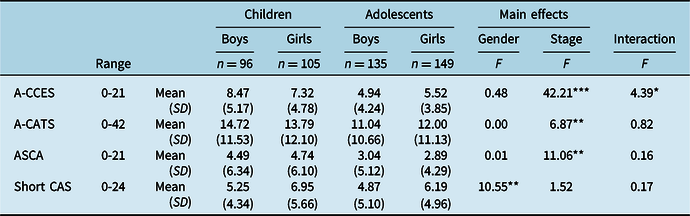

The average scores of the A-CCES and the A-CATS were calculated. The A-CCES (range: 0–21) scored 6.33 points (SD = 4.64), and the A-CATS (range: 0–42) scored 12.66 points (SD = 11.35). Children had higher cognitive errors, automatic thoughts and anger than adolescents. In addition, girls had significantly higher anxiety symptoms. Furthermore, there was a significant interaction effect for cognitive errors, but a post-hoc test did not show any significant results. Table 3 shows the average scores and standard deviations of the scales in this study.

Table 3. The average scores of the A-CCES, the A-CATS, the ASCA, and the Short CAS (n = 485)

A-CCES, Anger Children’s Cognitive Error Scale; A-CATS, Anger Children’s Automatic Thought Scale; ASCA, Anger Scale for Children and Adolescents; Short CAS, Short version of Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. ***p<.001, **p<.01, *p<.05.

Construct validity (hypotheses testing)

The correlation coefficient of each scale was calculated to examine construct validity of the A-CCES and the A-CATS. As a result, cognitive errors showed moderate positive correlation with anger (r = .44), and weak positive correlation with anxiety symptoms (r = .32). Next, automatic thoughts showed moderate positive correlation with anger (r = .59) and moderate positive correlation with anxiety symptoms (r = .47). Although the relationship between automatic thoughts and anxiety symptoms was higher than expected, three-quarters of the results supported our hypotheses. From the above, the construct validities of the A-CCES and the A-CATS were supported.

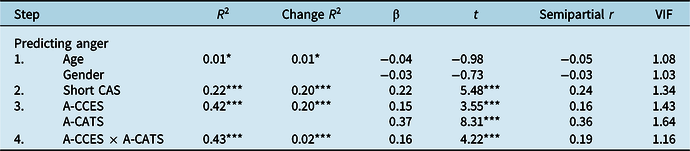

Hierarchical regression analysis

The final model of hierarchal regression analysis for anger is shown in Table 4. The result indicated that automatic thoughts positively and moderately related to anger (β = .37) after controlling for age, gender, anxiety symptoms, cognitive errors and interaction term. However, cognitive errors significantly but weakly related to anger (β = .15) after controlling for those variables, automatic thoughts and interaction term. Also, interaction term was significant but weakly related to anger (β = .15) after controlling for those variables, cognitive errors and automatic thoughts.

Table 4. Results of hierarchical regression analysis (n = 485)

A-CCES, Anger Children’s Cognitive Error Scale; A-CATS, Anger Children’s Automatic Thought Scale; ASCA, Anger Scale for Children and Adolescents; Short CAS, Short version of Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale. ***p < .001,**p < .01,*p < .05.

Mediation analysis

In order to examine the cognitive process influencing anger in children and adolescents, a mediation analysis was performed with anger as the dependent variable, cognitive errors as the independent variable, and automatic thoughts as the mediating variable. Results indicated that the standardization coefficient from cognitive errors to automatic thoughts (.47), automatic thoughts to anger (.50), and cognitive errors to anger (.20) were all significant. As a result of the mediation analysis, the standardization coefficient (.24) of the indirect effect of automatic thoughts was significant, and the confidence interval was not below zero (95% CI: .020 to .036). Thus, the cognitive process influencing anger in children and adolescents was supported. Figure 1 shows the cognitive process influencing anger in children and adolescents in this study.

Figure 1. The cognitive process influencing anger in children and adolescents.

Discussion

The purpose of this study was to develop new questionnaires for anger-provoking cognitive errors and automatic thoughts, and to examine relationships between anger, cognitive errors and automatic thoughts in children and adolescents. We developed the Anger Children’s Cognitive Error Scale (A-CCES) to measure hostile attribution bias, and the Anger Children’s Automatic Thought Scale (A-CATS) to measure automatic thoughts concerning blaming others. Results showed that both the A-CCES and the A-CATS had face validity, structural validity, internal consistency and construct validity (hypotheses testing). Finally, a hierarchal regression analysis indicated that automatic thoughts were positively and moderately related to anger in children and adolescents, while cognitive errors and interaction term were significantly but weakly related to anger. Finally, the mediation analysis indicated that automatic thoughts mediated the relationship between cognitive errors and anger in children and adolescents.

Factor analyses supported a single factor for anger-provoking cognitive errors and these items showed good internal consistency (α = .76). The result was consistent with our expectation because the A-CCES consisted of items only concerning hostile attribution bias. A systematic review, which investigated the relationship between hostile attribution bias and aggression subtype in children and adolescents (Martinelli et al., Reference Martinelli, Ackermann, Bernhard, Freitag and Schwenck2018), indicated two subtypes of hostile attribution: physical aggression-related and relational aggression-related biases. However, no reliable and valid scale to measure these hostile attribution biases has been used and no studies demonstrated discriminant validity of the two subscales of hostile attribution biases. Each situation in the A-CCES was developed using an open-ended question regarding anger-provoking situations which might be related to anger, but not to aggression. In the future, it will be necessary to examine potential subtypes of hostile attribution bias using reliable and valid scales.

Factor analyses also demonstrated a single factor for anger-provoking automatic thoughts concerning blaming others, and these items showed excellent internal consistency (α = .94). A previous study in late adolescents (Masuda et al., Reference Masuda, Kanetsuki, Sekiguchi and Nedate2005) indicated that blaming and criticizing other people may be anger-specific automatic thought. Our results supported the evidence that blaming and criticising other people were anger-specific automatic thoughts not only in late adolescents, but also in children and adolescents aged 9–15. In addition, the four items which had the highest factor loadings on the A-CATS (‘Cut it out!’, ‘Shut up’, ‘Annoying’ and ‘Go away!’) were relatively shorter and quicker words than the other items which had lower factor loadings (such as ‘Why do they talk to me as if they are better than me?’ and ‘I wish they wouldn’t say something like this all the time’). The results indicated that the shorter and quicker automatic thoughts concerning blaming others might be more important and essential for anger in children and adolescents rather than the longer and slower ones.

Empirical studies between anger and its cognitive variables are lacking despite the fact that many studies have demonstrated the role of specific cognitive errors and the content-specificity hypothesis of automatic thoughts for internalising or externalising problems in children and adolescents (Leung and Poon, Reference Leung and Poon2001; Schniering and Rapee, Reference Schniering and Rapee2004; Schwartz and Maric, Reference Schwartz and Maric2015). The unique contribution of this study involved revealing the relationships between anger, the anger-provoking cognitive errors (hostile attribution bias) and automatic thoughts (blaming others) in children and adolescents. However, anger-provoking cognitive errors and automatic thoughts were related to not only anger (r = .44; r = .59), but also anxiety (r = .32; r = .47). A systematic review indicated that irritability, an increased proneness to anger, is associated with anxiety disorders, depressive disorders, and oppositional defiant disorder longitudinally (Vidal-Ribas et al., Reference Vidal-Ribas, Brotman, Valdivieso, Leibenluft and Stringaris2016). Further research is needed to examine not only unique but also shared cognitive variables between co-occurring disorders and symptoms in children and adolescents.

In this study, we examined the relationship between anger, cognitive errors and automatic thoughts by conducting hierarchical regression analysis and mediation analysis. These results indicated that automatic thoughts are more strongly associated with anger, and therefore automatic thoughts can be a more proximal variable to anger. On the other hand, the effects of cognitive errors and interaction terms were shown to be smaller, suggesting that cognitive errors can be a more distal variable to anger. Furthermore, the indirect effect was significant, indicating that cognitive errors can produce automatic thoughts and that automatic thoughts can arouse anger. These results are in line with Beck’s cognitive model (Beck, Reference Beck1979; Beck et al., Reference Beck1979), and shows that the traditional model explaining the pathology of depression and anxiety in adults can be extended to anger in children and adolescents.

This study may provide clinical implications for treatment and prevention based on the cognitive model in children and adolescents. A previous study (Ishikawa, Reference Ishikawa2015) revealed that self-statements mediated relationship between cognitive errors and anxiety in community children and adolescents, while cognitive errors directly associated with anxiety in clinically anxious children and adolescents. Similarly, this study indicated that automatic thoughts, rather than cognitive errors and interaction term, were related to anger in community children and adolescents. Besides, the mediation analysis indicated that automatic thoughts mediated the relationship between cognitive errors and anger in children and adolescents. These results suggested that cognitive interventions focusing on automatic thoughts might be more underscored as interventions for preventing anger. On the other hand, cognitive errors had a small effect on anger after controlling automatic thoughts. Thus, it could be important to prioritise cognitive errors (hostile attribution bias) in treating externalising disorders and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) in clinical samples (Stoddard et al., Reference Stoddard, Sharif-Askary, Harkins, Frank, Brotman, Penton-Voak, Maoz, Bar-Haim, Munafò, Pine and Leibenluft2016; Sukhodolsky et al., Reference Sukhodolsky, Vitulano, Carroll, McGuire, Leckman and Scahill2009), but automatic thoughts (blaming others) might be essential in preventing anger in community or non-clinical samples.

This study has several limitations. First, we could not examine other aspects of reliability and validity of the A-CCES and the A-CATS, such as test–re-test reliability, criterion validity, responsiveness and interpretability. Future research is needed to examine other psychometric properties of the two scales. Second, it is difficult to clarify causal relationships because this study was a cross-sectional study. Longitudinal studies are needed to understand the relationship. Third, although it would be ideal to measure various mental health problems and cognitions, only anger, anxiety and anger-provoking cognition were measured in this study due to time constraints for the schools where our survey was conducted. Future research should include depressive symptoms, externalising problems, and other cognitions as a control variable to test the unique contribution of cognitive variables to the prediction of anger. Fourth, this study did not include clinically diagnosed children and adolescents. Anger in children and adolescents is related to various disorders, such as DMDD, oppositional defiant disorder, anxiety disorders and depressive disorders. DMDD is particularly relevant to anger in children and adolescents. Empirical studies using a sample of clinically diagnosed children and adolescents will be performed in the future.

To our knowledge, this study is the first to examine the relationship between anger, cognitive errors and automatic thoughts in children and adolescents using reliable and valid scales. The unique contribution of this study involved revealing the relationships between anger, cognitive errors and automatic thoughts in children and adolescents. Further research is needed to identify anger-specific cognition in children and adolescents, controlling for other mental health problems and cognitions.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Fumito Takahashi for his help in checking the scale items. We also thank the teachers and children for their participation in the study.

Author contributions

Kohei Kishida: Conceptualization (lead), Formal analysis (lead), Funding acquisition (lead), Methodology (lead), Project administration (lead), Resources (lead), Writing – original draft (lead), Writing – review & editing (lead); Masaya Takebe: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Chisato Kuribayashi: Conceptualization (equal), Funding acquisition (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal); Yuichi Tanabe: Conceptualization (equal), Data curation (lead), Writing – review & editing (equal): Shin-ichi Ishikawa: Conceptualization (equal), Supervision (lead), Writing – original draft (equal), Writing – review & editing (equal).

Financial support

This work was supported by a Research Grant for Public Health Science.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare none.

Ethical standards

The study was conducted with the approval of the Institutional Review Board of Doshisha University (18048). All authors abided by the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct as set out by the British Association for Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapists (BABCP) and British Psychological Society (BPS).

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.